Abstract

Wide-area damping controls, like the wide-synchronization control (WSC), are crucial for power system stability but are vulnerable to communication latencies. This article presents a comprehensive theoretical characterization of the impact of time delays on the WSC. The formal analysis derives mathematical models for both differential and common modes. Two distinct scenarios are investigated: a symmetric condition, where the WSC is applied to both coupled areas, and an asymmetric condition, where it is applied to only one area. A formal stability assessment is conducted to determine stability boundaries and critical delay-induced crossings into unstable regions. Key findings show that under symmetric conditions, the system remains stable for all delays, as latencies only affect the common mode. Conversely, the asymmetric condition introduces a coupling between modes, making the system susceptible to delay-induced instability, especially at high control gains. The work validates the theoretical findings through numerical experiments and evaluates the accuracy of various linear Padé approximant models for representing delays, highlighting how low-order models can fail to predict instabilities, requiring high-order approximants to guarantee adequate accuracy in the analysis.

1. Introduction

Wide-area damping control has become a cornerstone technique for augmenting small-signal stability in large interconnected power systems [1,2,3]. This category of wide-area controls relies on geographically dispersed synchronized measurements and wide-area communications to damp inter-area electromechanical oscillations, that local controllers cannot adequately attenuate. Recent studies and surveys summarize the practical value of wide-area damping control and emerging technologies such as grid-forming for increased stability of the system [4,5,6]. Several works also highlight the unique implementation challenges of wide-area controls, most notably addressing the influence of communication-induced time delays and latencies on closed-loop performance and robustness [7,8,9]. From a control-theoretic perspective, wide-area latencies enter the wide-area control feedback loop as transport delays that produce additional phase lag and effectively increase the loop order. These delays can originate from different factors, including the time required by the phasor measurement units (PMUs) to acquire the measurements and apply the timestamping, the processing and the buffering at phasor data concentrators (PDCs), the propagation of the signals across a given communication network, and the time required by the local actuators for the final command execution.

Assessing these latencies is crucial for wide-area damping control, because unmanaged time delays can cause the control system to amplify oscillations instead of damping them, possibly leading to power system instability. If latencies are not accurately assessed and compensated for, the corrective actions might sort unexpected and even deleterious effects [10]. Latencies cause a phase shift in the control signal, effectively turning positive, stabilizing damping into negative, destabilizing feedback. This might result in reinforcing the oscillations instead of stopping them, leading in the worst cases to critical stability conditions for the system. Even if the latency is not large enough to cause instability, it can still severely degrade the performance of the wide-area damping control. A delay means the applied control is lagging behind the expected and correct time of application, making it less effective at damping oscillations. Latencies should be therefore properly assessed to ensure effective damping in the system, enabling also a robust design of the controller, with the identification of delay margins and boundary stability conditions that the system can tolerate before becoming unstable [11,12,13]. The assessment of the delay is also useful to design compensation and countermeasures against the latencies [14,15], supporting a more precise design of counteraction methods such as phase-lead compensators or predictive control [16,17].

For all these reason, it is particularly important to have a proper characterization of the latencies in wide-area damping controls. The article aims to contribute in this field, providing a theoretical characterization of time delays and latencies for the wide-synchronization control (WSC), a novel wide-area damping control recently introduced in [18,19]. Even if an initial analysis of the concept has been provided, the impact of latencies on this wide-area damping control has not been comprehensively addressed, and several questions are still to be answered. A formal analysis through proper theoretical characterization and stability assessment is missing, and the impact of different modelling approaches for the delays has not been investigated. This work aims to answer these open points, providing a comprehensive investigation of the impact of the latencies on the wide-synchronization control. The contribution can be therefore summarized with the following points:

- Theoretical characterization, focusing on the differential and the common modes.

- Stability assessment, for both symmetric and asymmetric conditions.

- Investigation of different linear models for the representation of latencies.

While focusing on the specific on the specific control laws of the wide-synchronization control, the presented methodology can be generally applied to different control schemes, thus allowing the possibility of further comparative assessment with alternative wide-area damping control strategies. The remaining part of the article is organized as follows. The concept of the wide-synchronization control is briefly recalled in Section 2, with a particular focus on the mathematical background required to model the system including latencies. The theoretical characterization of the latencies in the wide-synchronization control is then derived in Section 3, where the common and the differential modes are examined for different WSC conditions. Based on the analysis derived in the theoretical characterization, a formal stability assessment is provided in Section 4, analyzing the magnitude and the phase conditions for boundary stability identification. The concepts are then applied and verified with numerical experiments in Section 5, confirming the theoretical considerations and also allowing further relevant observations. Finally, the conclusions are drawn in Section 6.

2. Wide-Synchronization Control

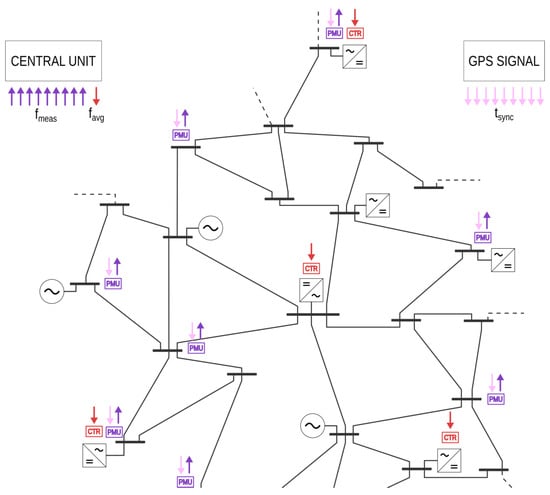

The concept of the wide-synchronization control, originally introduced in [18,19], is here summarized for providing adequate context. This wide-area damping control fundamentally relies on a reference frequency signal, calculated by averaging a set of frequency measurements taken from various nodes in the system. This reference frequency is the global feedback signal, which is transmitted to the control systems of the actuators. The actuation can be realized either by grid-forming or grid-following power converters. This concept has been originally formulated for a centralized architecture where a single computation unit handles all tasks: receiving all frequency measurements, determining the averaged reference frequency, and subsequently dispatching it to the actuators. Specifically, phasor measurement units send measured frequencies to phasor data concentrators, which forward the data to the top-level central unit. The central unit computes the average reference frequency and sends this signal to the local actuators, such as grid-forming or grid-following controlled generation sources. This concept is visually represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual representation of the WSC.

The governing equations of the WSC principle are:

and

In Equation (1), are the frequency measurements acquired by the PMUs in the system, N is the number of frequency measurements sent to the central unit, is the feedback signal computed by the central unit and sent to the actuators. In Equation (2), is the local frequency at the terminal of the actuator, is the reference average frequency sent from the central unit to the given actuator, is the gain which determines the intensity of the control, is transient active power change requested to the actuator.

In Equations (1) and (2), the dependence on time has been kept implicit. To explicit the presence of the latencies in the wide-synchronization control, the two equations can be rewritten as:

and

where is the time required to acquire the frequency measurements and send them to the central unit that will compute , is the time required to send the reference feedback signal to the actuators and execute the control actions for the transient injection of the power . The round-trip delay will be then given by the sum of all the latencies encountered in the process.

At system level, the wide-synchronization control can be examined referring to the slow coherency theory and representing the aggregated dynamics of the areas as [20]:

where and are frequency and angle of the area, respectively; is the starting time of the area, related to the inertia constant H through ; is the frequency droop of the area; is the total active power of the area; is the synchronizing coefficient between the coupled area i and area j, accounting for the impedance of the tie line between the areas; the terms represents the active power flow between area i and area j; is the rated angular frequency of the system, equal to denoting with the rated frequency; N is the number of areas of the system. It is important noting that Equation (5) hold under the following assumptions: network reduced to equivalent nodes and coherent areas, lines purely inductive, loads assumed as constant impedance sources, higher order dynamics of machines and controllers neglected. Despite the simplifying assumptions, the dynamics described by Equation (5) can be conveniently used to represent the essential wide-area dynamics of power systems. It is worth noting that the mutual interactions between the areas are solely described by the synchronizing coefficients that couple the angles . These interactions happens through the physical interconnections represented by the lines and the transformers of the system.

The application of the wide-synchronization control fundamentally modifies the dynamics of the system. The equivalent dynamics described in Equation (5) becomes:

As pointed out in Equation (7), the application of the wide-synchronization control introduces damping coupling terms between areas participating in the wide-area control. These damping couplings are the primary force responsible for the overall enhancement of the dynamic characteristics of the system. These damping-related terms are enforced between areas that are coupled through the overlaying communication system. It is worth noting that, with the application of the wide-synchronization control, the mutual interactions between the areas are additionally produced by the wide-area damping coefficients that couple the frequencies .

In conclusion of this section, it is relevant to present the approaches which can be used to represent the latencies in the overall mathematical model of the system. Especially in the perspective of linearized power system simulations, the time delays can be modelled with Padé approximants. This modelling approach corresponds to approximating the latency with polynomial rational functions, and it is a method commonly adopted for the representation of latencies in wide-area control schemes [21].

The transfer functions of different orders for the representation of the latencies are given by [22]:

It is worth noting that, since rational functions with numerator and denominator of same degree introduce a jump in the output at initial conditions, here approximations of the type with numerator one degree less than denominator have been also taken into examination.

3. Theoretical Characterization

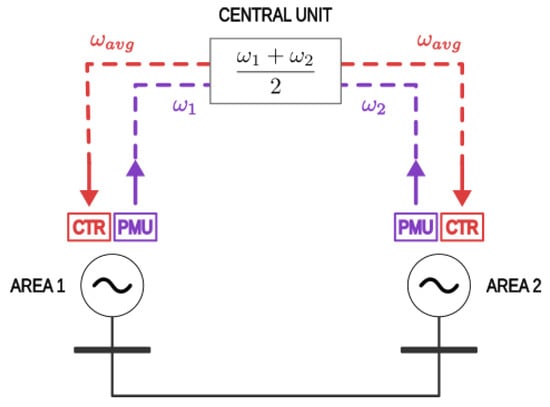

The formal analysis of the impact of the latencies on the wide-synchronization control is carried out referring to the representative two-area system of Figure 2. Despite the simple topology, this system is capable of representing the essential coupled dynamics between coherent areas of the system, as it will be shown later in the section. As previously discussed, the essential dynamics between coupled areas with the wide-synchronization control is the main focus of the paper. Also, a more complex system would be make a formal analysis basically impossible, preventing the derivation of relevant considerations about the theoretical characterization of the latencies and their impact on the wide-synchronization control.

Figure 2.

Representative two-areas system.

The equivalent dynamics of two areas coupled by a tie line can be described by the following linear system [20]:

For sake of simplicity in the analytical demonstration, the two areas are assumed to be identical and at initial zero steady-state conditions (i.e., ). All equations are therefore to be considered in per unit of the rated power of the area. Under these conditions, in the s-domain, Equation (15) read:

The formal analysis will be conducted considering the application of the wide-synchronization control in both areas (symmetric condition) and only in one area (asymmetric condition). In actual power systems, the latter can originate from different resources availability in the areas or from different policies of the transmission system operators. Asymmetric conditions might also occur due to deferred deployments or control system malfunctions.

3.1. Symmetric WSC Condition

With the application of the wide-synchronization control described by Equations (1) and (2) in both coupled areas, Equation (16) become:

where is the transfer function accounting for the delay .

Substituting , and bringing everything to the left-hand side, Equation (17) result:

For convenience of notation, it can be defined:

as transfer function of the area.

Collecting coefficients for and in each equation and rearranging, it results:

It can be noticed the symmetry of the system, having the same multiplying coefficients in the two equations. In fact, the linear system is in the form:

where the coefficients a and b are given by:

At this point, it is important to notice that, in the factor , the terms associated with the time delay cancel.

Therefore, the determinant of Equation (20) factors as:

By setting for non-trivial solutions, the characteristic equation splits into the product of the two modal factors.

It can be demonstrated that the two modal factors in Equation (25) correspond to the differential and the common mode of the system, respectively.

Defining:

for the differential (or synchronizing) mode, and:

for the common (or centroid) mode, the original system Equation (18) can be rewritten in these coordinates.

The differential mode is obtained by subtracting Equation (18), resulting in:

which is indeed the first modal factor in Equation (25). In the considered symmetric structure, the differential mode is therefore a delay-free mode of the system.

The common mode is obtained by summing Equation (18), resulting in:

which is indeed the second modal factor in Equation (25). In the considered symmetric structure, the common mode is therefore a delay-dependent mode of the system.

Collecting coefficients for and in each equation and rearranging in a matrix form, it results:

where the determinant is Equation (25). The zero off-diagonal terms in Equation (30) denote the complete decoupling between the two modes.

It is worth noting that the derivation of Equations (28) for the differential mode and (29) for the common mode could have been alternatively obtained by posing and , respectively.

From the analytical examination, it is possible to conclude that the delay in the signals sent to the actuators of the wide-synchronization control only affects the common mode dynamics of the system, which has the physical meaning of center of mass or system average frequency. The application of the wide-synchronization control in both coupled areas leaves instead the relative dynamics unchanged, as the differential delay is not affected by the delay, physically meaning that the synchronizing dynamics between the areas will be determined only by coupling stiffness and damping.

3.2. Asymmetric WSC Condition

With the application of the wide-synchronization control described by Equations (1) and (2) only in one area, Equation (16) become:

where is the delay transfer function as before. Substituting , and bringing everything to the left-hand side, Equation (31) result:

The analytical approach carried out before is here applied again, referring to the differential and the common modes of the system.

The differential mode is obtained by subtracting Equation (32), resulting in:

The common mode is obtained by summing Equation (32), resulting in:

Collecting coefficients for and in each equation and rearranging in a matrix form, it results:

where the presence of the off-diagonal terms denotes the coupling between the two modes.

Therefore, the characteristic condition for non-trivial solution is , explicitly reading:

It can be observed that the decoupling between pure common and differential modes does not subsist any longer. In the symmetric condition, where both areas implemented the WSC, the modal matrix was symmetric with identical off-diagonal terms and the determinant factorized. In the asymmetric condition, where only one area processes the signal provided by the central unit of the WSC, the modal matrix is not generally symmetric presenting a non-zero off-diagonal coupling between and . The delay now affects both modal dynamics, appearing in the common mode (coefficient multiplying into the equation of ) and in the coupling between the two modes (coefficient multiplying into the equation of ). Because of that coupling, the delay influences also the synchronizing mode, which was delay-free in the symmetric conditions. This means that the frequency and damping of relative oscillations may change, and new delay-induced instabilities are possible that mix common and relative dynamics of the system. This increases the risk that delay destabilizes synchronizing dynamics, creating more complex modal shapes and transient amplification of the system oscillations.

4. Stability Assessment

The main aim of this section is to examine the stability boundary, deriving explicit conditions for purely imaginary roots for the Hopf crossing, i.e., points where poles cross the imaginary axis. Generally, the impact of the delay can be studied examining the roots of the characteristic equation obtained from the determinant of the modal matrix.

4.1. Symmetric WSC Condition

Based on the analytical assessment derived for symmetric WSC conditions, the time delay only impacts the common mode dynamics of the system. The differential mode is instead completely unaffected. Referring to the linear system Equation (30), the impact of the delays on the system stability can be assessed examining the common mode. Since only one factor of the determinant in Equation (25) is dependent on the delay , the study can be limited to those corresponding roots of the characteristic equation. According to Equation (29), the factor of the common mode in the characteristic equation is:

The system in Equation (37) can be expressed in the form

separating the term without delay and the term multiplying the delay. It results:

The two conditions on magnitude and phase deriving from the Nyquist stability criterion can be then examined.

The stability boundary condition on the magnitude is expressed by:

where the variable is to be solved for computing the critical frequency crossing the imaginary axis.

The stability boundary condition on the phase is expressed by:

which leads to:

where is a crossing frequency identified with Equation (40) and k a positive integer.

Applying Equation (40) with Equation (39):

which immediately shows that, considering that all physical parameters are positive, there is no real frequency at which the poles can cross the imaginary axis. The impact of the delay is therefore confined to how the common mode behaves in terms of transient response, but not in terms of system stability. Under the considered symmetric WSC conditions, despite including the effect of the delays, the common mode remains stable for all values of , as the poles never cross the imaginary axis into the right-half plane. The overall stability of the system is therefore guaranteed. This conclusion is to be related to the symmetric nature of the WSC application, where the global feedback signal is used in both coupled areas for the implementation of the wide-area damping control.

4.2. Asymmetric WSC Condition

Based on the analytical assessment derived for asymmetric WSC conditions, the time delay impacts both common and differential mode of the system. Referring to the linear system Equation (35) and its determinant Equation (36), the characteristic equation to be studied is given by:

which is a quasipolynomial equation due to the presence of the time delay term . The analytical solution of Equation (44) is impractical due to the high complexity of the expression. A qualitative assessment of the stability can be still derived, referring to the same analytical approach followed for the symmetric case.

Applying Equations (38)–(44), after expanding, collecting and simplifying, the two polynomials read:

where it has been posed:

for compact notation.

Substituting in Equation (45) and applying the condition Equation (40) on the magnitude, it results:

where it has been posed:

The stability condition on the magnitude can be analysed for two limiting cases, i.e., small and high values of the gain .

For very small values of the gain (), the condition Equation (47) becomes:

This condition Equation (49) is fulfilled if one of the two magnitudes is zero:

requiring that both the real and imaginary parts have to be zero simultaneously. From Equation (50), it can be immediately observed that, for positive parameters , the required condition is never verified for any real frequency . The magnitude of the first term can not be zero as the real part will always be positive. For the magnitude of the second term, the imaginary part is zero only if , but at zero frequency the real part will always be positive. As tends to 0, the two terms in Equation (49) are strictly positive and their product can never be zero. There is no real frequency that satisfies the condition on the magnitude as tends to 0. Consequently, for sufficiently small , it results for all , and the equality in the magnitudes cannot be satisfied. From a physical point of view, this means that small values of the gain effectively remove the delayed path in Equation (44), so the characteristic becomes dominated by P alone. Delay-induced crossings of the imaginary axis into the unstable region of the plane cannot occur.

For very high values of the gain (), the condition Equation (47) becomes:

which, expanded and simplified, leads to:

Apart from the zero solutions due to the quadratic term , this equation yields two possible solutions:

Looking for a real frequency , the numerator of Equation (47) must be positive, implying . For the typical values of these parameters in actual power systems, this condition is normally verified. Consequently, for high , crossings of the imaginary axis into the unstable region exist, since there are some finite frequencies solving the stability condition on the magnitude. As the gain increases, the condition becomes independent on the value of . From a physical point of view, this means that, for very large , the delayed path dominates. The system becomes sensitive to latencies in the wide-synchronization control, the stability margin will be reduced, and there are critical delays which will possibly lead to the instability of the system.

In general, for values of the gain between the two limiting cases, there will be intermediate values where the cancellation in the magnitude condition Equation (47) can occur at one or more frequencies . For very small , crossings into the unstable region are unlikely to occur, and the system is robust to delay effects originating in the wide-synchronization control. For very large , crossings into the unstable region are generically present, and their frequencies are determined solely by the physical characteristics of the electric system.

Substituting in Equation (45) and applying the condition Equation (42) on the phase, it results:

and then substituting Equation (48) and simplifying:

The stability condition on the phase can be analysed for two limiting cases, i.e., small and high values of the gain .

For very small values of the gain (), the condition Equation (54) becomes:

As tends to 0, the term divided by dominates, and the phase of the entire expression is therefore determined by the phase of that term. Since is a positive scalar, the gain does not affect the argument.

It is worth noting that Equation (56) represents the mathematical limit of the phase condition. However, as observed previously, the magnitude condition is never satisfied as tends to zero. Therefore, in the limiting case of tending to zero, no stability boundary exists. The system becomes unconditionally stable, and the time delay has no impact on stability.

For very high values of the gain (), the condition Equation (54) becomes:

which should be evaluated at the critical frequencies satisfying the magnitude condition.

It can be immediately observed that the phase and therefore the critical values of the delay become independent of , and they are determined only by the parameters and the crossing frequency . From a physical point of view, this means that, for large values of the gain , a stability boundary always exists at non-zero critical frequency . This boundary corresponds to a critical time delay: if the actual delays in the wide-synchronization control are close to this value, the system will have reduced stability margins, or in worst cases it will become unstable.

In general, both limiting conditions on the gain lead to well-defined phases and hence to the expressions given by Equations (56) and (57), respectively for very small and very high values of the gain. For intermediate values of between the two limiting cases, the phase changes from scaling with for very small values of the gain, to scaling with the factor for large values of the gain. Eventually, the phase becomes independent of for very large values. It is also worth observing that the critical values of the delays and therefore the impact of the gain strongly depend on the critical frequency. Since appears at the denominator of the expression, the same change in the phase due to at a low critical frequency produces a much bigger change in the critical delay than at high critical frequencies.

Finally, it is worth examining what happens for values of the gain intermediate between very small and very large values. The phase in Equation (55) is expressed by:

and then, properly collecting and factorizing:

where it has been posed:

From Equation (59), it can be immediately observed that modifies only the phase of the numerator. For the denominator, a varying only scales the magnitude, leaving the phase unaffected, as it multiplies both real and imaginary parts. For the numerator, a varying produces a monotonic change of the phase, moving along a straight line in the complex plane. The direction of this movement is determined by the derivative of the numerator in Equation (59) with respect to the gain . It can be demonstrated that, for positive real crossing frequency , the sign of the derivative is ultimately determined by the sign of the term , which results in:

Therefore, whether the phase in Equation (58) increases or decreases as grows depends on the product in Equation (61). If the product is positive, decreases with , leading to smaller values of critical time delays . Vice-versa, if the product is negative, the phase increases with , leading to bigger values of critical time delays . In the edge case of product zero, the phase is independent of the gain . These theoretical considerations indicate that the gain of the wide-synchronization control has a negative impact on the phase as well, since high values of the gain would determine smaller limit values for acceptable latencies.

5. Numerical Experiments

The theoretical analysis about the impact of latencies on the wide-synchronization control is here assessed with numerical experiments. The purposes of the numeric application can be summarized as follows:

- Validate the theoretical assessment, while providing a numerical example.

- Study the impact of different linear models for the latencies representation.

- Examine the sensitivity of the most relevant parameters of the system.

The numerical application is performed for the reference system of Figure 2. The baseline parameters are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline parameters for numerical experiments.

The theoretical characterization presented in the previous sections is here applied to the numerical case study, considering the two derived stability boundary equations, i.e Equations (47) and (55), with the baseline parameters reported in Table 1.

It is interesting to note that the approximations in Equations (53) and (57) for high values of the gain give:

which are not far away from the actual values computed with the exact expressions. It is also relevant to notice that, for the given numerical parameters, the product in Equation (61) is positive:

meaning that the phase decreases as the gain increases, then negatively leading to smaller values of critical time delays . It is important to note that time delays of wide-area damping control are typically in the range of some hundreds of milliseconds. While for the considered hypothetical two-area system the critical latencies are in the order of seconds, for actual power systems these values may differ substantially, depending on the complex characteristics of electric grid and communication network.

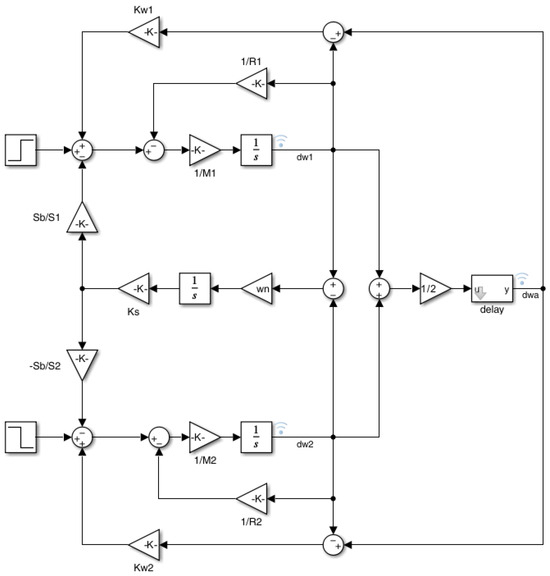

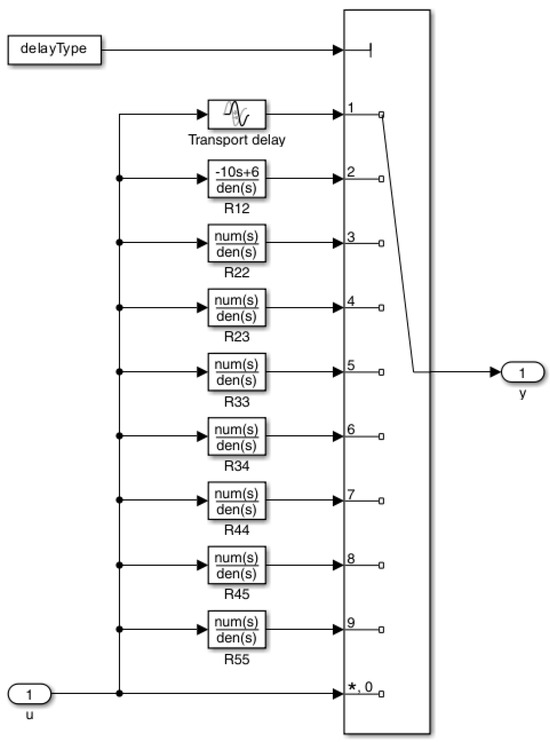

The numerical experiments are carried out with both modal analysis and time domain simulations. In the modal analysis, the eigenvalues of the linearized systems are computed for different models of the latencies. According to the mathematical background presented in the previous sections, the linearized system is studied with the space-state matrices reported in Appendix A. For the time domain simulations, the system is studied with a model implementation in MATLAB/Simulink, as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Simulink implementation—Top level model.

Figure 4.

Simulink implementation—Latency subsystem.

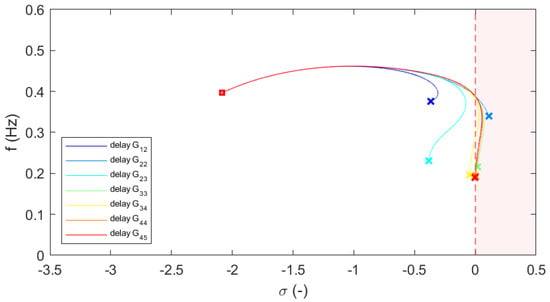

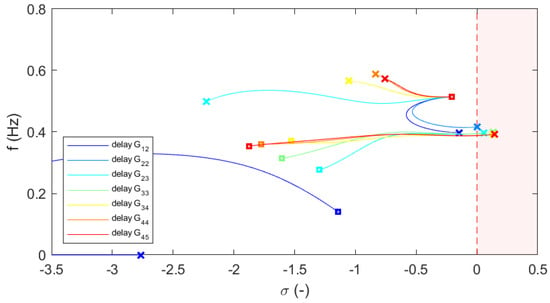

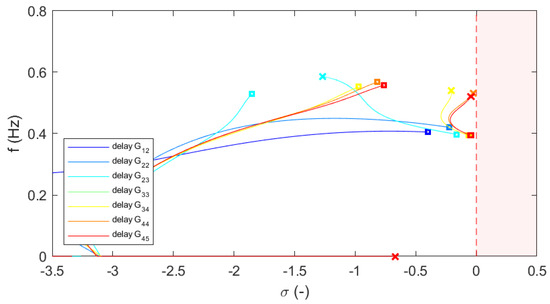

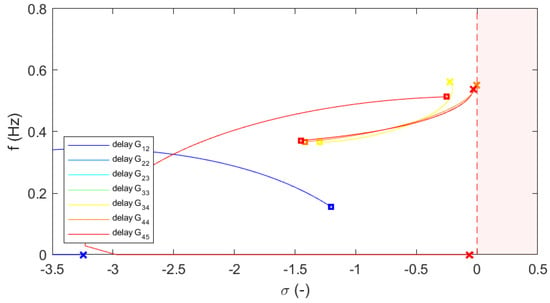

The eigenvalues of the linearized system are repeatedly computed for a parametric sweep of the most relevant parameters. The starting points are marked with squares, whereas the ending points are marked with crosses. The results for a parametric sweep of the time delay are shown in Figure 5, where the delay has been varied in the range 0.02–5 s. Beside the parametric analysis for time delay , the eigenvalues are also computed for different variations of the WSC gains and , since they have the most relevant impact on the system stability in presence of latencies. In the evaluations of varying parameters and , the time delay is fixed to the critical value s computed previously with the exact formula. The results for a parametric sweep of the gain are shown in Figure 6, where the gain is varied in the range 1–1000 pu. The results for a parametric sweep of the gain are shown in Figure 7, where the gain is varied in the range 1–1000 pu. The results for a simultaneous parametric sweep of the gains and are shown in Figure 8, where the gains are both varied in the range 1–1000 pu.

Figure 5.

Critical eigenvalues for parametric sweep in .

Figure 6.

Critical eigenvalues for parametric sweep in .

Figure 7.

Critical eigenvalues for parametric sweep in .

Figure 8.

Critical eigenvalues for simultaneous parametric sweep in and .

The main observations which can be drawn from the numerical results are the following:

- For asymmetric WSC conditions, there is a critical delay which leads to the instability of the system. The delay representations and generally fail, since they represent a stable system for all time delays (see Figure 5).

- For asymmetric WSC conditions, high values of the gain will make the system unstable. The delay representations and fail, since they do not catch the actual instability of the system (see Figure 6).

As validation, verification, and completion of the observations derived with the analysis of the linearized system, time domain simulations of the MATLAB/Simulink model are also performed. The simulations are carried out by fixing boundary stability conditions for the system. For that, the crossing of the imaginary axis into the unstable region are identified for the different cases as reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Identified boundary parameters.

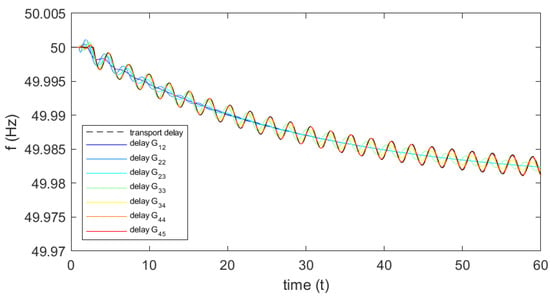

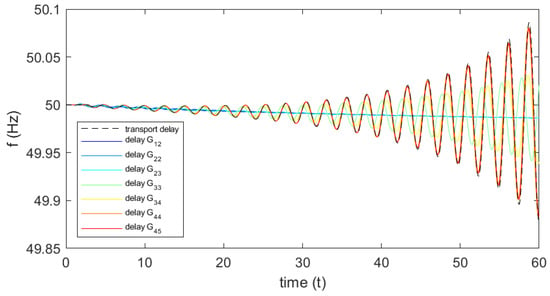

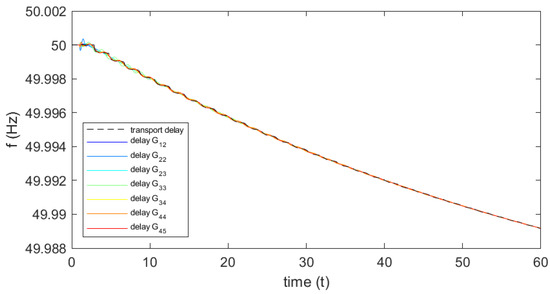

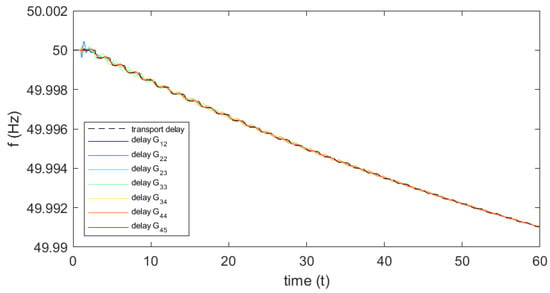

The first set of time domain simulations is performed fixing the time delay to s. The results are shown in Figure 9. From the simulations, it can be immediately confirmed the observation #1: the representations and of the latencies fail in catching the actual instability of the system, as indicated by the reference transport delay (black line) and by the more accurate fractional representations. The simulations are then performed by fixing the gains of the wide-synchronization control beyond the identified boundary values. The results of the time domain simulations with fixed gain pu are shown in Figure 10. The results confirm the expected instability for increased values of the gain. The impact of is significant, as the amplitude of the oscillations rapidly increase. The simulations also confirm the observation #2, showing that the functions and fail in representing the actual transient behaviour of the system with latencies. The results of the time domain simulations with fixed gain pu are shown in Figure 11, while the results of the simulations with fixed gains in both areas pu and pu are shown in Figure 12. The results confirm the expected stability of the system under the application of the WSC in both areas. According to observation #3, the actual conditions of the system are stable for any combination of the gains and , even in presence of critical latencies and with very high gains, as shown by the model with the reference transport delay (black line) and by all the implemented Padé approximations. These considerations align then with the theoretical characterization, also suggesting how the participation in the wide-synchronization control of all the areas makes the control concept much more robust and effective.

Figure 9.

System frequency for boundary conditions from sweep in .

Figure 10.

System frequency for boundary conditions from sweep in .

Figure 11.

System frequency for boundary conditions from sweep in .

Figure 12.

System frequency for boundary conditions from sweep in and .

6. Conclusions

The article provides a detailed theoretical investigation into the effects of delays and latencies on the wide-synchronization control for damping power system oscillations. A critical distinction is identified between the symmetric and asymmetric application of the control, yielding significant insights into system stability. The theoretical analysis, confirmed by numerical experiments, demonstrates that when the wide-synchronization control is applied symmetrically to both areas of a coupled system, the differential (synchronizing) mode is unaffected by time delays. This decoupling ensures robust stability against inter-area oscillations, as the latencies only impact the common mode, which is also shown to remain stable. In sharp contrast, the asymmetric application of the wide-synchronization control in only one area introduces a coupling between the differential and the common modes. This coupling makes the synchronizing dynamics of the system dependent on the delay, creating a significant risk of instability. This vulnerability is exacerbated by high control gains , which are shown to reduce the stability margin. The study also highlights the critical importance of selecting appropriate linear models for representing latencies. Numerical simulations reveal that common low-order approximants will likely fail to predict the delay-induced instabilities found in the asymmetric case. High-order approximants are therefore required for an accurate prediction of the system stability, and the linear analysis should be complemented with time domain simulations whenever possible. Approximating symmetric condition, the implementation of the wide-synchronization control in all the areas of the system is inherently more robust and resilient to the negative impacts of time delays. In all cases, a careful validation of delay models used in stability analysis is needed to guarantee a proper accuracy in the results.

This work provides an initial theoretical assessment of the effects of latencies in the wide-synchronization control, focusing on a hypothetical two-area system to derive the essential characterization. With the established theoretical framework, the main observations will be further verified for larger interconnected systems with multiple inter-area oscillation modes, as part of future developments of the research. Further works with more complex systems will also give the opportunity to delve into relevant aspects such as impact of large disturbances and robustness analysis under different ranges of operating conditions. Building on the concepts provided in this work, future studies will then allow an advanced assessment of the latencies in the wide-synchronization control applied to existing power systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, R.M.; writing—review and editing, M.L.D.S. and L.M.; supervision, S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The appendix reports the state-space matrices used for the analysis of the linearized system. In the formulation of all matrices, it has been posed:

Matrix :

Matrix :

Matrix :

Matrix :

Matrix :

Matrix :

Matrix :

References

- Zhang, X.; Lu, C.; Liu, S.; Wang, X. A review on wide-area damping control to restrain inter-area low frequency oscillation for large-scale power systems with increasing renewable generation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmy, Y.; Yu, Z.; Shi, D.; Weng, Y. Wide-Area Measurement System-Based Low Frequency Oscillation Damping Control through Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 5072–5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musca, R.; Riva Sanseverino, E.; Guerrero, J.M.; Vasquez, J.C. Wide-Area Damping Control for Clustered Microgrids. Energies 2025, 18, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Xiao, J.; Lu, C.; Han, Y. Wide-area stability control for damping interarea oscillations of interconnected power systems. IEE Proc. Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2006, 153, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaksonen, H. Improvement of Power System Frequency Stability with Universal Grid-Forming Battery Energy Storages. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 10826–10841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Wang, S.; Elizondo, M.A.; Hansen, J.; Huang, R.; Fan, R.; Kirkham, H.; Marinovici, L.D.; Schoenwald, D.; Wilches-Bernal, F. Universal Wide-Area Damping Control for Mitigating Inter-area Oscillations in Power Systems. In Pacific Northwest National Laboratory Technical Report; Pacific Northwest National Lab (PNNL): Richland, WA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Bhadu, M. A Comprehensive Study of Wide-Area Damping Controller Requirements Through Real-Time Evaluation with Operational Uncertainties in Modern Power Systems. IETE J. Res. 2023, 69, 8382–8403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Jiang, L.; Wen, J.; Wu, Q.; Cheng, S. Wide-Area Damping Controller of FACTS Devices for Inter-Area Oscillations Considering Communication Time Delays. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2014, 29, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, M.E.C. Fixed Low-Order Wide-Area Damping Controller Considering Time Delays and Power System Operation Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 3918–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyizere, D.; Letting, L.K.; Munyazikwiye, B.B. Effects of Communication Signal Delay on the Power Grid: A Review. Electronics 2022, 11, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Dassios, I.; Tzounas, G.; Milano, F. Stability Analysis of Power Systems with Inclusion of Realistic-Modeling WAMS Delays. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabian, M.; Bagheri, A. Design of adaptive wide-area damping controller based on delay scheduling for improving small-signal oscillations. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 133, 107224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Yang, D.; Liu, C. Adaptive Wide-Area Damping Control Scheme for Smart Grids with Consideration of Signal Time Delay. Energies 2013, 6, 4841–4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Song, B.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Y. Time-varying delays and their compensation in wide-area power system stabilizer application. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2015, 73, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyagarajan, P.; Vairakannu, S. Signal selection and latency compensation in wide area controlled power system. Energy Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 3885–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzounas, G.; Sipahi, R.; Milano, F. Damping Power System Electromechanical Oscillations Using Time Delays. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2021, 68, 2725–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, M.E.C. A New Method to Design Resilient Wide-Area Damping Controllers for Power Systems. Energies 2025, 18, 5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musca, R.; Riva Sanseverino, E.; Zizzo, G.; Giannuzzi, G.; Pisani, C. Wide-Synchronization Control for Power Systems with Grid-Forming Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 4998–5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippolito, M.G.; Musca, R. A novel wide-area control for general application to inverter-based resources in power systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 160, 110086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundur, P.; Balu, N.J.; Lauby, M.G. Power System Stability and Control; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Vittal, V. Design of Wide-Area Power System Damping Controllers Resilient to Communication Failures. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 4292–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajta, M. Some Remarks on Padé-Approximations. In Proceedings of the 3rd TEMPUS-INTCOM Symposium, Veszprém, Hungary, 9–14 September 2000. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).