Abstract

Contamination of drinking water by potentially toxic elements (PTEs) remains a critical public-health concern in Uganda. This systematic review compiled and harmonized quantitative concentrations (mg/L) for key PTEs, lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), chromium (Cr), mercury (Hg), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), nickel (Ni), cobalt (Co), manganese (Mn), and iron (Fe), across various potable and informal water sources used for drinking, including municipal tap water, boreholes, protected and unprotected springs, wells, rainwater, packaged drinking water, rivers, lakes, and wetlands. A comprehensive search of different databases and key institutional repositories yielded 715 records; after screening and eligibility assessment, 161 studies met the inclusion criteria, and were retained for final synthesis. Reported PTE concentrations frequently exceeded WHO and UNBS drinking water guidelines, with Pb up to 8.2 mg/L, Cd up to 1.4 mg/L, As up to 25.2 mg/L, Cr up to 148 mg/L, Fe up to 67.3 mg/L, and Mn up to 3.75 mg/L, particularly in high-risk zones such as Rwakaiha Wetland, Kasese mining affected catchments, and Kampala’s urban springs and drainage corridors. These hotspots are largely influenced by mining activities, industrial discharges, agricultural runoff, and corrosion of aging water distribution infrastructure, while natural geological conditions contribute to elevated background Fe and Mn in several regions. The review highlights associated health implications, including neurological damage, renal impairment, and cancer risks from chronic exposure, and identifies gaps in regulatory enforcement and routine monitoring. It concludes with practical recommendations, including stricter effluent control, expansion of low-cost adsorption and filtration options at household and community level, and targeted upgrades to water-treatment and distribution systems to promote safe-water access and support Uganda’s progress toward Sustainable Development Goal 6.

1. Introduction

Access to safely managed drinking water remains a significant challenge in Uganda, despite decades of government and donor investment in water supply infrastructure. National statistics indicate that only about 72% of urban residents and 67% of rural Ugandans have access to improved water sources [1,2]. This leaves roughly one-third of rural areas and nearly one-quarter of urban centers dependent on untreated or minimally treated sources such as shallow wells, boreholes, open springs, rivers, lakes, rainwater, and informal vendors. While these sources are often more accessible, they are susceptible to contamination, which undermines their reliability and poses significant public health risks. Furthermore, rapid population growth, urbanization, and industrial expansion have steadily increased the demand for potable water [3,4].

Among the most pressing threats to water quality are PTEs, which represent some of the most persistent and harmful pollutants in Uganda’s water systems [5,6]. Unlike microbial pathogens that cause acute illnesses, PTEs such as arsenic (As), lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), and chromium (Cr) are chemically stable and non-biodegradable, allowing them to persist in the environment and bioaccumulate in human tissues. Chronic exposure can result in neurological impairment, organ toxicity, developmental delays in children, and increased cancer risk [7,8]. Their persistence and non-degradable nature make them an invisible but formidable barrier to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 6, which seeks universal access to safe water [9,10].

Multiple factors drive PTE contamination in Uganda’s water sources. Geogenic sources contribute a baseline load; the weathering of mineral-rich rocks elevates concentrations of As, Cr, and other elements in groundwater [11,12]. However, anthropogenic activities are the dominant sources of new PTE inputs. Mining operations, in particular, have left a legacy of contamination. For instance, decades of copper (Cu) and cobalt (Co) mining at the Kilembe mines in Kasese District generated sulfide-rich tailings containing extremely high levels of Cu, Co, Pb, and As [13,14]. Over time, weathering and seasonal flood events have leached these PTEs into the surrounding soils, groundwater, and surface waters.

Artisanal and small-scale gold mining in eastern and northern Uganda (Busia, Karamoja, and Acholi regions) also contributes to PTE pollution. Mercury is widely used for gold extraction, and improper handling of mercury-amalgamated tailings leads to mercury release into the surrounding soils and potable water sources [15,16]. Additionally, gold ores often contain arsenic-bearing minerals like arsenopyrite, which may release As into groundwater during mining [17,18]. Wells in the Busia district have recorded As levels above the WHO limit of 0.01 mg/L, directly implicating nearby gold mining activities [19]. Other mineral extraction activities (tin, tungsten, and iron ore) similarly mobilize elements such as Cr, Ni, and Co when mine wastes are not properly contained [20].

Rapid industrialization and urban growth are further exacerbating PTE contamination. Around Kampala, Jinja, Entebbe, and other urban centers, industrial discharges from metal processing, tanning, battery manufacturing, and petrochemical plants often flow untreated into drainage channels and wetlands. Kampala’s Nakivubo channel carries untreated urban and industrial effluent into Lake Victoria’s Murchison Bay [21,22]. Agricultural practices add to the burden: long-term use of phosphate fertilizers (often containing cadmium impurities) and past application of lead-arsenate pesticides introduce trace metals like Cd, Pb, and As into soils, some of which can leach into groundwater and runoff [23,24]. Field surveys across Uganda confirm the widespread extent of contamination. Studies have documented Pb, Cd, Hg, and As levels exceeding international and national guidelines in both rural and urban water supplies in Uganda [25,26,27]. These patterns suggest that PTE contamination is a persistent issue with geographic and source-specific variability.

In light of these concerns, this systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of PTE contamination in Uganda’s potable water sources. The objectives were as follows: (i) summarize key natural and anthropogenic pollution sources, (ii) categorize potable water supply types and their associated contamination risks, (iii) compile and compare reported metal concentrations with international (WHO) and national (UNBS) standards, and (iv) discuss the associated health impacts and potential mitigation strategies. By integrating findings from peer-reviewed literature, government reports, and academic theses, this review fills a critical gap. There has been no prior comprehensive review on PTE contamination in Uganda’s drinking water systems. This review informs policymakers, water managers, and public health practitioners about the extent of PTE contamination in Uganda and recommends measures to safeguard water quality. The review was designed and reported in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 statement for systematic reviews [28].

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted in full accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines for transparent and comprehensive reporting [28]. All PRISMA checklist items have been addressed, and a completed PRISMA 2020 flow diagram is included in the results section. The review protocol was not prospectively registered in PROSPERO or any registry. Completed PRISMA 2020 checklists are attached as Supplementary Materials.

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A systematic approach was used to identify and synthesize eligible studies reporting PTE concentrations in Uganda’s drinking water sources, covering the period from 2000 to 2025. Both peer-reviewed and gray literature were included, comprising journal articles, government and utility reports, academic theses, and technical documents from NGOs and regional agencies. No restrictions were applied regarding publication year. The databases and search engines consulted were Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. Boolean keyword combinations tailored to the Ugandan context were applied, including the following: “Uganda” AND (“drinking water” OR “potable water”) AND (“PTEs” OR “trace metals”), together with specific metal names (Pb, Cd, As, Cr, Hg, Cu, Zn, Ni, Mn, Fe, Co). Only studies that reported quantitative data on PTE concentrations were retained. To supplement the indexed literature, gray literature sources were also included. These comprised government archives, technical reports, and institutional repositories from the Ministry of Water and Environment (MWE), National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA), National Water and Sewerage Corporation (NWSC), and East African regional water-quality reports. Reference lists of all eligible studies were screened to identify additional sources. The most recent database search was completed in November 2025.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (i) were conducted within Uganda; (ii) reported measured concentrations of at least one target metal in a drinking-water context: and (iii) provided sufficient methodological detail, including sampling description and analytical techniques. For the purposes of this review, “drinking water” refers to water that has undergone treatment and is distributed for human consumption through regulated systems, such as National Water and Sewerage Corporation (NWSC) piped supplies and certified packaged (bottled or sachet) water. “Drinking water sources” refer to raw or minimally treated water bodies that are routinely used directly for drinking at the household or community level, including boreholes, protected and unprotected springs, shallow wells, rivers, lakes, wetlands, and harvested rainwater.

Studies were excluded if they (i) lacked quantitative concentration data; (ii) focused solely on microbiological contaminants; (iii) reported only wastewater, industrial effluents, or non-potable environmental matrices; (iv) were conducted outside Uganda; (v) represented duplicate datasets or secondary reviews of previously screened records.

2.3. Data Collection and Extraction Variables

A standardized extraction form was applied. Three reviewers independently extracted information from each eligible report, and discrepancies were resolved through a consensus process. Extracted variables included publication year, study location (district or region), water-source type (treated versus untreated), sample size (where reported), analytical techniques (AAS, ICP-MS, or equivalent), limits of detection (when available), and the minimum and maximum concentrations reported for each metal. Concentration values reported in µg/L were harmonized to mg/L for comparability. Values below the detection limit were recorded as “–” and retained as presented in the original publication.

2.4. Risk of Bias and Certainty Assessment

Quality and risk of bias were appraised using an adapted OHAT/Joanna Briggs Institute exposure-assessment tool. The evaluation considered sampling representativeness, clarity of analytical procedures, calibration, and QA/QC reporting, and data presentation transparency. Each study was assessed for methodological strength and categorized as low, moderate, or high risk of bias. Only studies that met the minimum methodological threshold were retained for inclusion in the synthesis.

2.5. Data Handling, Evidence Synthesis, and Reporting

All extracted data were organized by PTE and water-source category and grouped by geographical region (Central, Western, Eastern, and Northern Uganda). Due to heterogeneity in study methodologies, meta-analysis was not conducted. A descriptive synthesis approach was used. PTE concentrations were compared against drinking water guideline values from the WHO Guidelines for Drinking Water (2017; 2022) [29], Uganda Standard US EAS 12:2014 (UNBS, 2014) [30], U.S. EPA National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) (2015) [31], and Council for Directive 98/83/EC (EU, 1998) [32], drinking-water standards to determine exceedances. Results are presented in tabular and graphical formats, including regional comparisons and maximum-concentration exceedance plots.

2.6. Limitations

This review has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. First, although a comprehensive search strategy was applied across multiple databases and gray literature sources, only studies published in English were included, which may introduce language bias. The reliance on published and accessible reports also means that relevant data from unpublished institutional documents or restricted-access archives may not have been captured. In addition, methodological variability across the included studies, such as differences in sampling design, analytical techniques, and reporting formats, may influence the comparability of PTE concentration values and contribute to heterogeneity in the synthesized findings. The review did not perform a formal meta-analysis due to these methodological inconsistencies. Although a structured quality-appraisal tool was used, the certainty of the evidence remains influenced by the varying strengths of the individual studies. Lastly, this review relied on literature available up to November 2025, meaning that more recent monitoring data may not be captured.

3. Contextual Background

3.1. Drinking Water Sources in Uganda

Uganda’s drinking water comes from diverse sources that differ in quality, reliability, and accessibility. The main categories include groundwater sources (boreholes, wells, and springs), surface waters (rivers, lakes, streams), piped and packaged water systems, and rainwater harvesting. Among these, groundwater remains the most relied-upon source, especially in rural areas where centralized supply infrastructure is limited.

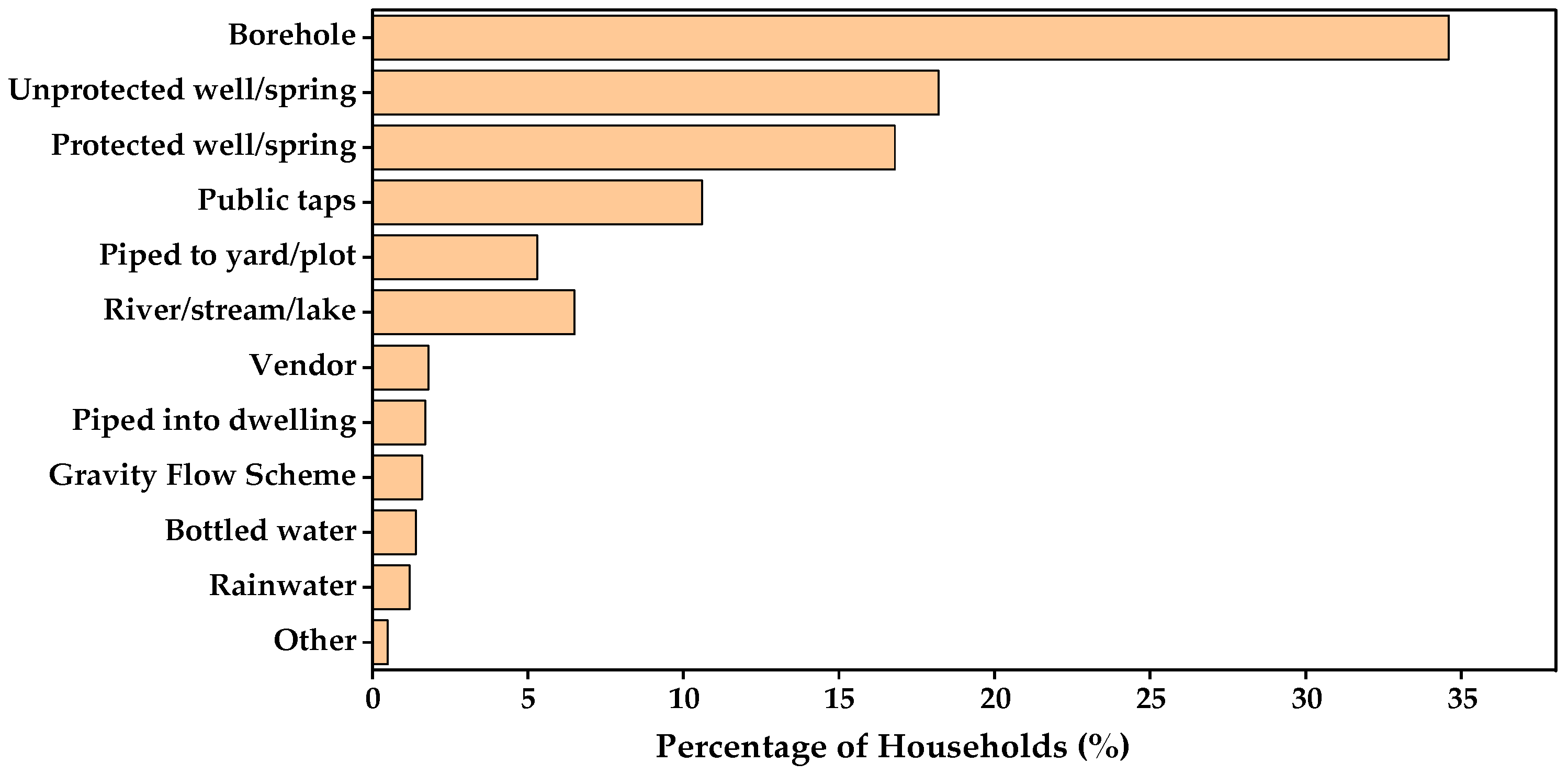

According to the Uganda National Household Survey (2012/13), boreholes supply approximately 35% of households nationwide, while unprotected wells and springs account for about 18%. Public taps serve roughly 11% of households, and only about 2% are connected to piped water within dwellings. Surface water from lakes and rivers contributes around 7% of the drinking water supply, whereas rainwater harvesting, bottled water, and vendor-supplied sources together account for less than 5% (Figure 1) [33]. These statistics highlight Uganda’s continued dependence on groundwater and unimproved sources, particularly in rural settings where access to safely managed piped systems remain limited.

Figure 1.

Main sources of drinking water in Uganda (extracted from the Uganda national household survey 2012/13 [33].

In urban areas, treated water supplied through piped systems operated by the NWSC constitutes the primary formal drinking water source. However, network coverage is incomplete, and service interruptions are common, particularly in informal settlements that remain unserved or intermittently supplied, leading residents to rely on alternative sources such as springs, shallow wells, and vendor-distributed water [34]. As a result, a substantial proportion of the population continues to consume water from sources that are untreated or only minimally protected.

While treated piped water is subject to routine operational monitoring within NWSC systems, most decentralized and informal drinking-water sources, including unprotected springs, shallow wells, surface waters, and wetlands, are not covered by continuous national drinking-water surveillance. Consequently, information on water quality and PTE contamination in these sources is largely derived from academic studies, NGO-led assessments, district-level surveys, and targeted research investigations. Each drinking-water source type, therefore, presents distinct advantages as well as specific contamination vulnerabilities, which are discussed in the subsections that follow.

3.1.1. Groundwater Sources

An estimated 65–70% of Ugandan rural households rely on groundwater sources, primarily boreholes and protected springs [35]. Properly constructed boreholes and protected springs are generally considered “improved” sources because they incorporate basic engineering features such as concrete linings, sealed aprons, and drainage channels that reduce direct exposure to surface contamination. In contrast, unprotected springs and shallow hand-dug wells lack such physical barriers and remain directly exposed to human activity, animal access, waste disposal, and overland flow, making them common but high-risk sources in underserved and remote areas [36].

These unimproved groundwater sources are associated with elevated risks of both microbial and chemical pollution, especially when located near pit latrines, waste dumps, agricultural fields, or mining sites [37]. Even improved groundwater sources can exhibit substantial variability in quality. Local hydrogeological conditions may result in naturally elevated concentrations of iron, manganese, or arsenic, while anthropogenic activities can introduce additional contaminants into aquifers [38]. Although well construction details were not consistently reported across the reviewed studies, shallow hand-dug wells typically tapping near-surface aquifers (<10 m) were more frequently associated with elevated contamination than deeper boreholes (>30 m), reflecting differences in aquifer protection and vulnerability. In agricultural regions, the long-term use of fertilizers and pesticides may contribute to nitrates and trace metals such as cadmium infiltration into groundwater, whereas boreholes situated near mining areas may intersect metal-rich geological formations or zones affected by mine tailings. Although groundwater quality is often perceived as a relatively stable source, numerous studies indicate that wells and springs located in mineralized or intensively disturbed zones frequently exceed recommended drinking water safety thresholds [39].

3.1.2. Surface Waters

Rivers, lakes, wetlands, and streams serve as key water sources for communities located in proximity to these water bodies or where groundwater is scarce. Uganda is endowed with extensive surface water resources, including the Nile River and large lakes such as Victoria, Kyoga, Albert, and George [36]. Fishing villages and lakeshore communities often rely almost entirely on lake or river water for domestic use. In parts of northern and eastern Uganda, seasonal rivers and streams serve as critical fallback sources during dry periods when wells and springs run dry. However, surface waters are highly susceptible to contamination. These bodies receive untreated municipal wastewater, industrial effluents, mine leachate, and agricultural runoff, introducing PTEs and other pollutants. For example, the Nyamwamba River in Kasese is contaminated by leachates from the Kilembe copper mine, while Murchison Bay in Lake Victoria receives heavily polluted runoff from Kampala [13,40,41]. Fertilizer and pesticide residues containing As, Cu, and Zn further degrade surface water quality. Despite the known risks, these sources remain widely used, often under the belief that boiling is sufficient for safety, particularly in drought conditions.

3.1.3. Piped and Packaged Water

Urban and peri-urban water supply is primarily managed by the National Water and Sewerage Corporation (NWSC), which treats and distributes surface water, and in some locations groundwater, through centralized piped systems [42]. While initial water quality is typically high due to effective conventional treatment processes such as coagulation, filtration, and disinfection. However, system limitations persist: network coverage remains incomplete, many informal settlements lack direct connections, and aging infrastructure can lead to post-treatment deterioration, including metal leaching from iron or lead-containing pipes and groundwater intrusion in low-pressure sections of the network [35,43].

Packaged drinking water, including bottled and sachet water, is widely consumed in urban areas as an alternative to the piped supply. Although most products comply with UNBS standards, specifically US EAS 12:2014 (Potable Water—Specification) [30], elevated PTE concentrations have been reported in some cases. For example, lead concentrations up to 0.24 mg/L and chromium as high as 1.0 mg/L have been reported in some bottled samples from Kampala [40,44]. Such exceedances are likely linked to variability in source-water quality, treatment effectiveness, leaching from bottling equipment, or prolonged storage in substandard containers, particularly among small-scale producers, and this highlight the need for consistent quality control and regulatory oversight.

3.1.4. Rainwater Harvesting

Rainwater harvesting, primarily from rooftop catchments, is an important supplemental source, particularly in island and rural communities. Freshly collected rainwater tends to have low metal content, but its quality is influenced by roofing materials and storage practices. Galvanized iron roofs may leach zinc and lead, and contamination from debris or animal droppings can occur during collection [45]. Boiling does not remove these metals, thus emphasizing the need for safe storage systems and basic filtration [46]. Despite its limitations (seasonality and need for maintenance), rainwater remains among the safest available sources when properly managed.

3.2. Sources of PTE Contamination in Uganda

Uganda’s water resources are exposed to PTEs from both anthropogenic and natural sources. Anthropogenic activities, including mining, industrial discharges, agriculture, and urban waste, tend to form localized hotspots of elevated contamination, whereas natural geochemical processes contribute a diffuse background load of certain metals. Understanding these distinct sources is essential for interpreting water quality and designing targeted remediation strategies. The relative contributions of each category are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Estimated relative contribution of major anthropogenic and natural sources to PTE contamination in Uganda’s water resources, based on synthesized evidence from reviewed studies.

3.2.1. Anthropogenic Sources

Mining and Mineral Processing

Mining has long been central to Uganda’s economy, and its environmental legacy is evident in PTE contamination of local water sources. Both large-scale operations and small-scale artisanal mining can release toxic metals into surrounding soils and surface waters. The Kilembe copper–cobalt mine in western Uganda exemplifies this impact: decades of mining left behind vast piles of tailings rich in Cu, Co, Pb, Zn, and As, such as the Nyamwamba and Mobuku, where lead concentrations up to 8.2 mg/L, cadmium 1.4 mg/L, and arsenic 4.3 mg/L, orders of magnitude above WHO limits [13,47]. Communities downstream report health problems potentially linked to this exposure [48]. Similarly, small-scale gold miners in Busia, Karamoja, and Acholi use mercury and disturb arsenic-bearing ores. These activities have contaminated nearby soils and water. Indeed, groundwater near Busia’s gold fields reported As exceeding 0.01 mg/L (the WHO guideline) [19,49]. Other mining districts (e.g., Buhweju, Kabale) dealing with tin or tungsten often mobilize Cr, Ni, and other metals when waste is not contained [50,51].

Industrial Discharges

Uganda’s expanding industrial sector, especially around Kampala, Jinja, Mbarara, and Entebbe, has become a major contributor of PTEs to water systems [52]. Many industries operate without adequate wastewater treatment. Effluents from smelters, tanneries, battery recyclers, textile mills, and paint factories contain Pb, Cd, Cr, Ni, and Cu. In Kampala’s Nakivubo Channel, concentrations of Pb (12 to 16 mg/L) and Cd (7 to 8 mg/L) have been reported, exceeding WHO limits by several orders of magnitude [25]. These effluents deposit contaminants that accumulate in sediments and flow into Lake Victoria’s Murchison Bay, degrading Kampala’s main drinking water source [53]. Similar patterns are observed in Jinja, where leather and metal industries discharge Cr and Ni, and in Mbarara, where municipal and industrial effluent adds Mn, Pb, and Cr into the Rwizi River. Unregulated industrial effluents, therefore, remain a major driver of PTE hotspots across Uganda’s urban centers.

Agricultural and Livestock Activities

Agriculture is a key diffuse source of metal loading in Uganda’s aquatic systems. Runoff from fertilized cropland and livestock farms introduces Cd, Pb, Zn, Cu, As, and Fe into nearby streams and wetlands [54]. In surface and drainage waters around Kampala and other cultivated zones, Cd (0.01–0.09 mg/L), Pb (0.04–0.31 mg/L), Cu (0.01–0.30 mg/L), Zn (≤3.1 mg/L), and Fe (≤11.8 mg/L) have been detected at elevated concentrations [55,56]. These elevated concentrations result mainly from phosphate-fertilizer impurities, residual pesticides, and livestock manure rich in Cu and Zn. Irrigation through metal-rich soils, particularly those in the Albertine Graben, further mobilizes Cr and vanadium [57]. Consequently, agriculture and livestock practices substantially raise background PTE levels in regional water resources.

Urban Runoff and Municipal Waste

Rapid urbanization in Uganda has outpaced waste management capacity [58]. Widespread dumping of solid waste, including batteries, e-waste, and paints, releases metals (Pb, Cd, Hg, and Cr) into soils and stormwater. In many slums, sewage and greywater enter the ground unchecked. For instance, Kampala’s Kiteezi landfill, Pb-enriched leachate has been linked to elevated blood-lead levels in nearby children [59,60]. Open burning of waste in informal settlements such as Katwe and Bwaise releases airborne metals that settle in wetlands and streams [61]. Moreso, corrosion of old galvanized or lead-soldered pipes under acidic conditions releases Zn, Fe, and Pb [62]. Surveys in Kampala have reported Pb in tap water ranging from 0.10 to 0.40 mg/L, exceeding the 0.01 mg/L WHO limit [44]. Vehicular traffic (lead from old gasoline, Zn, and Cu from tire and brake wear) also deposits metals into dust and runoff [63]. Together, these diffuse urban sources elevate metals in community water supplies, especially unprotected wells and springs.

3.2.2. Natural Geochemical Sources

Even in the absence of human activity, Uganda’s geology naturally enriches water with metals. Much of the country lies within the mineral-rich East African Rift Valley system [64]. Groundwater moving through lateritic and igneous formations often dissolves iron and manganese. As a result, iron is commonly the highest metal in Ugandan waters. For instance, studies have found rural wells averaging 4–5 mg/L Fe, with some as high as 43 mg/L. Manganese often co-occurs and can exceed its 0.4 mg/L limit (e.g., one spring in Kampala reached 1.5 mg/L) [65]. Geological arsenic hotspots exist as well: certain gold-bearing zones (e.g., near Busia) naturally leach As into groundwater 52]. Such geogenic inputs mean that even water from pristine areas can have elevated Fe, Mn, and occasionally As. While iron and manganese at those levels are more of an aesthetic issue [66], they indicate the geochemical context and can signal where other metals (like As or Hg) might also be present.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Study Selection and Characteristics of Included Studies

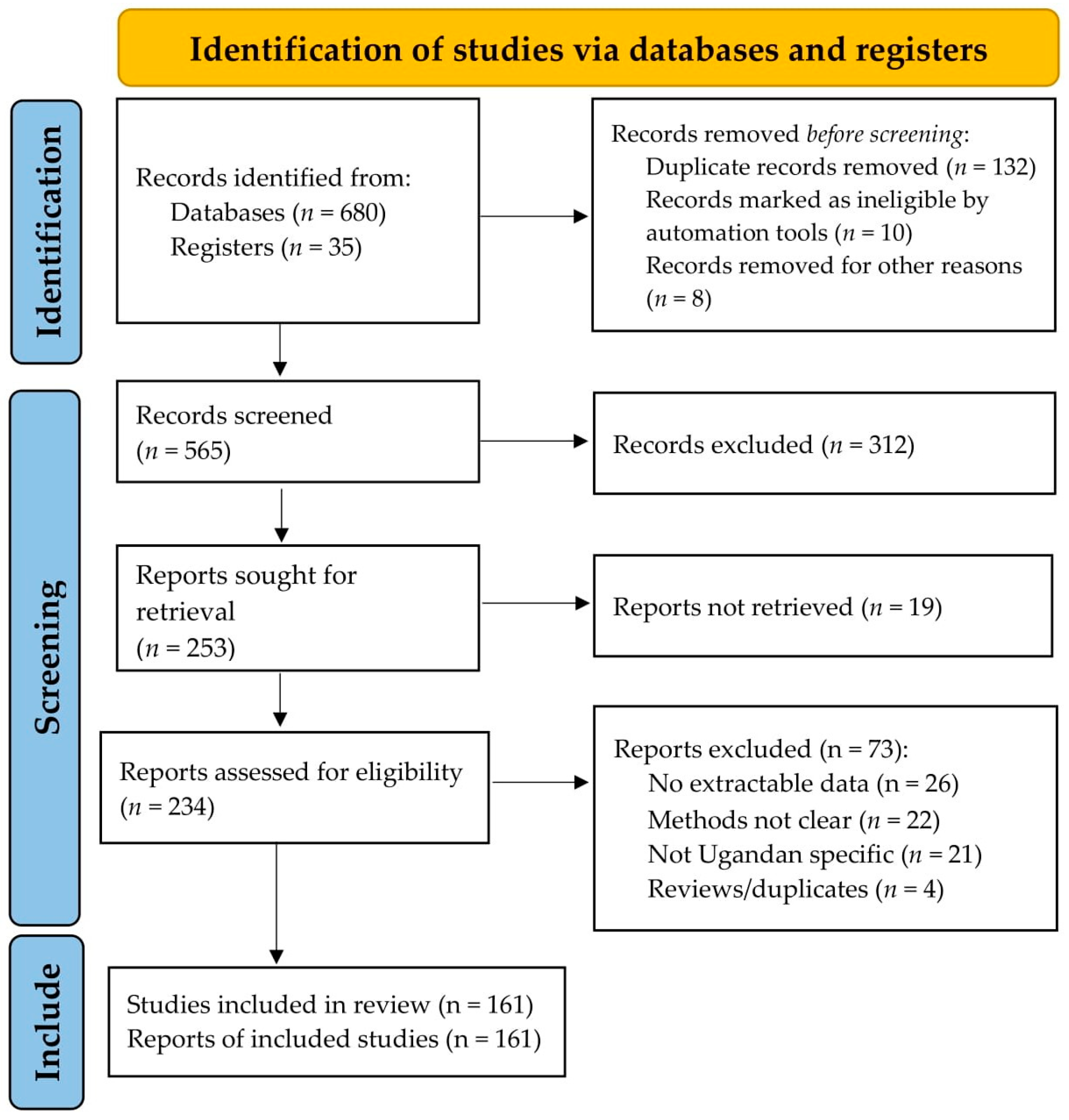

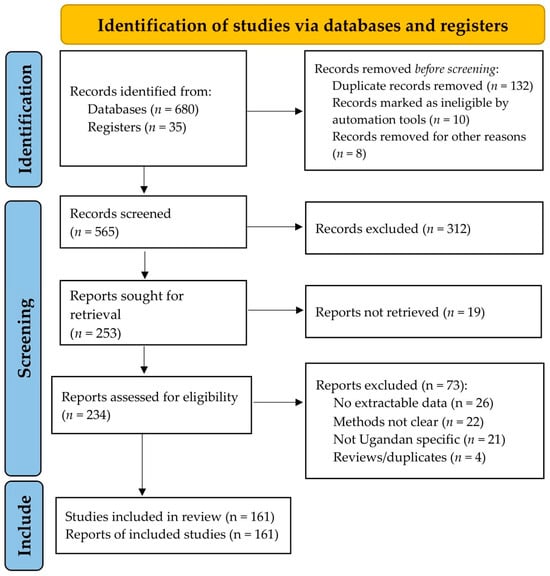

The systematic search initially identified 715 records. After removing 132 duplicates, a total of 565 unique records remained for screening. Title and abstract screening led to the exclusion of 312 records that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Full-text retrieval was sought for 253 reports, of which 19 could not be retrieved. The remaining 234 reports were assessed for eligibility. A total of 73 were excluded due to the following: no extractable data (n = 26), unclear methodology (n = 22), not Uganda-specific (n = 21), or reviews/duplicates (n = 4). This resulted in 161 studies that met the inclusion criteria for review. The entire identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion processes are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the identification, screening, exclusion, and inclusion process.

All 161 studies were retained following quality appraisal and included in the descriptive synthesis. The included studies reported concentrations of at least one target PTEs across major water-supply sources in Uganda. Considerable variation was observed with respect to sample size, analytical methods, and geographical coverage. Despite this variability, consistent patterns of elevated concentrations were observed for several metals, particularly for Pb, Cd, As, Fe, and Mn. The highest concentrations were most frequently documented in mining-impacted districts of Western Uganda, while elevated Pb levels in some urban springs and shallow wells suggested additional contamination from plumbing infrastructure and urban runoff.

Overall, the descriptive synthesis confirms that PTE contamination remains a concern across multiple drinking water-source categories in Uganda. Distinct spatial and source-related patterns indicate the combined influence of legacy mining operations, industrial discharges, agricultural runoff, and urbanization on water quality. These findings highlight persistent public-health risks associated with chronic exposure to metals such as Pb, Cd, As, and Cr(VI) and underscore the need for strengthened monitoring systems, regulatory enforcement, corrosion-control interventions, and protection of communities reliant on vulnerable water sources.

4.2. PTE Concentration in Ugandan Drinking Water Sources

PTE contamination in Uganda’s drinking-water sources exhibits pronounced spatial and temporal variability due to differences in geology, anthropogenic inputs, and treatment coverage. Both natural mineral dissolution and human activities, such as mining, waste disposal, and corrosion of distribution systems, contribute to elevated metal concentrations [67]. Drinking-water guideline values for potentially toxic elements provide the benchmarks used to evaluate measured concentrations, particularly for Pb, Cd, As, Cr, and Hg (Table 2). These benchmarks are intended to protect human health across diverse exposure settings.

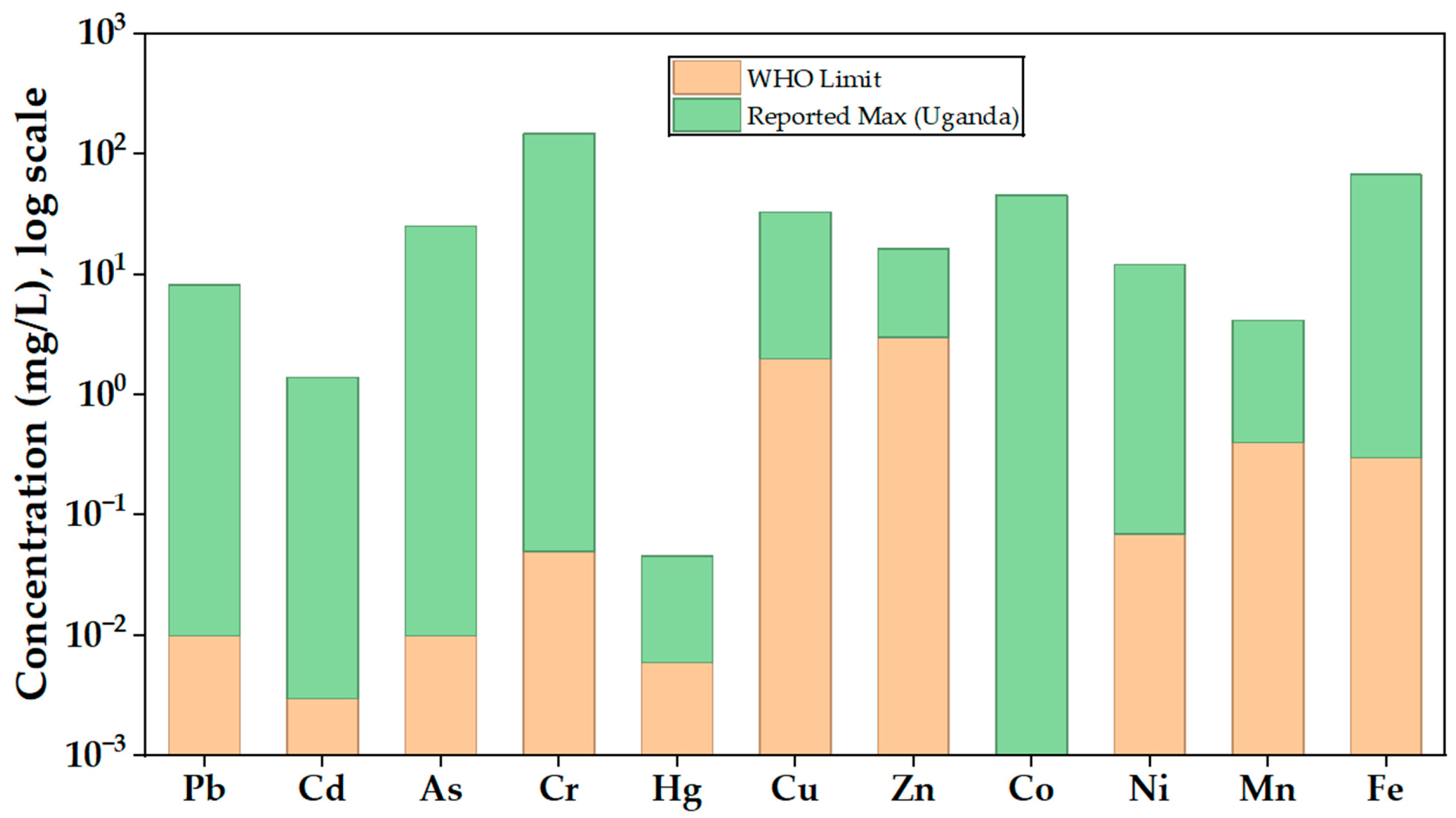

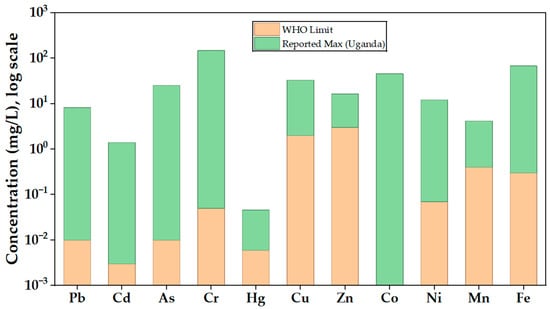

Reported PTE levels in Ugandan drinking water sources, summarized from published studies conducted between 2000 and 2025 (Table 3), show substantial variation by region and source type. Field observations indicate that concentrations in many untreated or poorly protected water sources often exceed guidelines, especially for Fe, Mn, Pb, and Cd. A comparison of reported maxima concentrations with WHO drinking water guideline values (Figure 3) demonstrates that, in several cases, reported maxima exceed WHO guideline values by several orders of magnitude. For example, total chromium concentrations of up to 148 mg/L have been reported relative to the guideline value of 0.05 mg/L limit, iron up to 67 mg/L relative to 0.3 mg/L, and lead up to 8.21 mg/L relative to 0.01 mg/L [68]. Such exceedances indicate persistent contamination risks arising from both natural and anthropogenic sources. While treated municipal supplies generally meet standards, sporadic violations continue to be reported in groundwater, protected springs, and mining-influenced rivers. The following subsections examine the occurrence, sources, and implications of individual metals in Uganda’s drinking-water systems.

Figure 3.

Reported maxima concentrations of PTEs in Ugandan potable and drinking water sources (2000–2025) compared with the WHO drinking water guideline limits. Concentrations are represented on a logarithmic (base-10) scale to accommodate the wide range of reported values spanning several orders of magnitude.

Table 2.

Health-based and esthetic guideline limits for PTEs in drinking water (mg/L) as established by selected national and international regulatory agencies.

Table 2.

Health-based and esthetic guideline limits for PTEs in drinking water (mg/L) as established by selected national and international regulatory agencies.

| Agency | Pb | Cd | As | Cr | Hg | Cu | Zn * | Co | Ni | Mn | Fe ** | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNBS (2014) | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.001 | 1.00 | 5.00 | – | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.30 | [30] |

| WHO(2008) | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.006 | 2.00 | 3.00 | – | 0.07 | 0.40 | 0.30 | [29] |

| USEPA (2015) | 0.015 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.002 | 1.30 | 5.00 | – | 0.10 | 0.05 ¥ | 0.30 | [31] |

| EU (2023) | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.001 | 1.00 | – | – | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.20 | [69] |

* Zn has only a secondary (esthetic) drinking water standard (3–5 mg/L); ** Fe has only an aesthetic guideline value (0.3 mg/L) for color and taste; no health-based value is established by the WHO. ¥ The U.S. EPA’s value of 0.05 mg/L for Mn represents a non-enforceable health advisory; some U.S. states use secondary or operational thresholds in the range of 0.3–0.5 mg/L; – indicates that no drinking-water guideline value is available or specified by the respective agency.

The highest reported concentrations of chromium and arsenic are confined to a small number of mining-impacted sites and wetlands, notably Rwakaiha Wetland and the Kasese catchments, and should therefore be interpreted as localized extremes rather than indicative of typical national drinking-water conditions, as illustrated by the wide concentration ranges shown in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Reported ranges of potentially toxic element concentrations (mg/L) in Ugandan potable water sources (2000–2025).

Table 3.

Reported ranges of potentially toxic element concentrations (mg/L) in Ugandan potable water sources (2000–2025).

| Water Source | Region/ Location | Reported Ranges of PTE Concentrations (mg/L) | References | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Cd | As | Cr | Hg | Cu | Zn | Co | Ni | Mn | Fe | |||

| Central Uganda | |||||||||||||

| Tap Water | Kampala | 0.02–0.31 | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.04 | 0.01–0.76 | – | 0.01–0.17 | 0.01–0.34 | 0.02–0.30 | [44] |

| Borehole Water | Kampala | 0.00–0.02 | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.09 | 0.00–0.12 | – | – | 0.00–0.06 | 0.00–0.24 | [12] |

| Bottled Water | Kampala | 0.00–0.02 | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.03 | 0.01–0.07 | – | – | – | 0.01–0.03 | |

| Surface Water | Kampala | 0.11–0.41 | – | 0.01–0.01 | – | – | 0.01–0.06 | – | – | 0.01–0.37 | 0.02–1.50 | 0.01–0.08 | [44] |

| Protected Spring | Kampala | 0.10–0.41 | 0.01–0.09 | 0.00–0.01 | 0.01–0.09 | 0.01–0.04 | 0.09–0.25 | 0.01–0.25 | – | 0.05–0.37 | 0.09–1.50 | 0.06–0.93 | [11,40,44,70] |

| Ground Water | Kampala | 0.10–0.41 | 0.01–0.10 | 0.01–0.10 | 0.01–0.09 | – | 0.08–0.30 | – | – | – | 0.00–3.10 | 0.01–11.8 | |

| Shallow Well | Kampala | 0.06–0.29 | 0.02–0.09 | – | – | – | 0.19–0.29 | – | – | – | 0.18–3.10 | 5.23–11.8 | |

| Open Spring | Kampala | 0.12–0.23 | 0.02–0.09 | – | – | – | 0.08–0.27 | – | – | – | 0.22–0.62 | 0.11–0.80 | |

| Shallow wells | Kampala | 0.11–0.31 | 0.01–0.09 | – | – | – | 0.09–0.29 | – | – | – | 0.21–3.10 | 0.01–3.86 | |

| Open springs | Kampala | 0.12–0.23 | 0.00–0.09 | – | 0.01–0.03 | – | 0.09–0.26 | – | – | – | 0.12–0.62 | 0.08–0.62 | |

| Kitante Stream | Kampala | 0.03–0.06 | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.05 | – | – | – | 0.01–0.16 | 0.05–0.25 | [25] |

| Lugogo Stream | Kampala | 0.02–0.07 | – | – | – | – | 0.02–0.03 | – | – | – | 0.01–0.47 | 0.30–1.00 | |

| Kibira Road Stream | Kampala | 0.03–0.11 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.47 | 0.30–1.25 | |

| Rainwater | Kampala | 0.01–0.03 | – | – | – | – | 0.02–0.16 | – | – | – | 0.01–0.05 | 0.05–0.20 | |

| Katanga Wetland | Kampala | 0.08–0.25 | – | – | – | – | 0.03–0.08 | 0.25–0.56 | – | – | – | – | [54] |

| Kyebando Wetland | Kampala | 0.05–0.15 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.09–0.90 | – | – | – | – | |

| Namuwogo Wetland | Kampala | 0.03–0.05 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Munyonyo Wetland | Kampala | 0.01–0.03 | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.05 | 0.01–0.02 | – | – | – | – | |

| Kinawataka Wetland | Kampala | 0.03–0.05 | – | – | – | – | 0.02–0.04 | 0.01–0.16 | – | – | – | – | [59] |

| Kinyarwanda well | Entebbe | 0.01–0.02 | – | – | 0.01–0.02 | – | – | 0.02–0.45 | – | – | – | – | |

| Nakiwogo well | Entebbe | 0.03–0.08 | 0.01–0.02 | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.15 | – | 0.03–0.05 | – | – | |

| Katoogo Spring | Wakiso | – | – | – | 0.01–0.05 | – | – | 0.01–0.04 | – | – | – | – | |

| Lake Victoria (Ggaba) | Wakiso | 0.01–0.20 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.03 | – | 0.01–0.03 | – | – | [21,71] |

| Lake Victoria (Wagagai) | Wakiso | – | – | – | 0.02–0.80 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lake Victoria (Nakiwogo) | Wakiso | 0.01–0.20 | – | – | 0.01–0.70 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lake Victoria (Kasenyi) | Wakiso | 0.01–0.30 | – | – | 0.02–0.70 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Lake Victoria (Kigungu) | Wakiso | 0.01–0.40 | – | – | 0.01–0.80 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Katoogo Spring | Wakiso | – | – | – | 0.01–0.05 | – | – | 0.01–0.04 | – | – | – | – | [56] |

| Murchison Bay | Wakiso | 0.02–0.20 | – | – | 0.10–0.20 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [21] |

| Kalangala Bay | Kalangala | 0.01–0.20 | – | – | 0.01–0.20 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Protected Springs Water | Wakiso | – | – | – | 0.32–0.61 | – | 0.01–0.07 | – | – | – | 0.13–0.57 | 0.02–0.19 | [72] |

| Western Uganda | |||||||||||||

| Kitengure Stream | Buhweju | – | 0.08–0.20 | – | – | – | 0.04–0.08 | – | – | – | – | – | [48] |

| River Mobuku | Kasese | 0.01–0.47 | 0.12–0.44 | 0.00–0.49 | 0.79–13.5 | – | 0.07–2.00 | 1.05–5.56 | 0.01–0.02 | – | – | 0.90–6.02 | [12,13,14,47,48,73,74] |

| River Nyamwamba | Kasese | 0.40–8.21 | 0.05–1.40 | 0.22–4.34 | 1.05–3.10 | – | 0.21–10.7 | 5.11–13.4 | 0.01–0.25 | 0.07–12.0 | – | 10.2–34.6 | |

| River Rwimi | Kasese | 0.02–0.07 | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.80 | 0.01–0.08 | 0.01–0.25 | – | – | – | |

| River Rukoki | Kasese | – | 0.03–0.06 | – | – | – | 0.00–0.11 | 0.00–0.04 | 0.00–0.07 | 0.00–0.02 | 0.00–0.10 | 0.10–0.60 | |

| Kilembe Valley | Kasese | 0.01–0.05 | 0.01–0.05 | – | – | – | 0.11–2.60 | 0.02–1.00 | 0.36–3.90 | 0.20–1.00 | – | – | |

| River Ngangi | Kasese | – | 0.00–0.01 | – | – | – | 0.05–0.79 | 0.03–0.10 | 0.01–0.30 | 0.03–0.10 | – | – | |

| River Kanyarubogo | Kasese | – | 0.01–0.02 | – | – | – | 0.02–0.61 | 0.02–0.20 | 0.02–0.30 | 0.02–0.20 | – | – | |

| River Kyanjuju | Kasese | – | 0.00–0.10 | – | – | – | 0.01–0.12 | 0.01–0.05 | 0.00–0.10 | 0.00–0.10 | – | – | |

| Lake George | Kasese | – | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.30 | 0.04–0.10 | 0.07–0.16 | 0.02–0.12 | – | – | [75,76] |

| River Mpanga | Kabarole | 0.01–0.10 | – | 0.01–13.8 | – | – | 0.03–0.05 | – | – | – | – | – | [27] |

| Rwakaiha Wetland | Kabarole | – | – | 8.89–25.2 | 38.2–148 | – | 8.17–30.8 | 17.0–45.6 | – | – | – | [68] | |

| Southwestern Uganda | |||||||||||||

| River Rwizi | Mbarara | 0.04–2.00 | 0.00–0.04 | – | – | – | 0.04–0.70 | 0.03–2.66 | 0.02–0.08 | – | 0.04–3.75 | 0.15–67.3 | [77] |

| Surface Water | Mbarara | 0.09–0.25 | 0.02–1.49 | – | – | – | 0.09–0.44 | – | – | – | 0.08–2.84 | 0.09–5.33 | [11,78] |

| Groundwater | Mbarara | 0.11–0.20 | 0.02–0.11 | – | – | – | 0.09–0.31 | – | – | – | 0.02–3.75 | 0.01–11.8 | |

| Open Pond | Mbarara | 0.12–0.30 | 0.01–0.08 | – | – | – | 0.10–0.33 | – | – | – | 0.12–0.51 | 1.03–4.44 | |

| Borehole Water | Bushenyi | 0.01–0.03 | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.02 | 0.01–0.02 | – | – | 0.23–0.79 | 0.02–0.79 | |

| Shallow Well Water | Bushenyi | – | 0.02–0.16 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.03–0.78 | [12] |

| Open Well Water | Bushenyi | 0.02–0.03 | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.02 | 0.01–0.02 | – | – | – | 0.30–1.27 | |

| Tap Water | Bushenyi | 0.02–0.03 | – | – | – | – | 0.02–0.08 | 0.14–0.76 | – | – | – | 0.05–0.39 | |

| Bottled Water | Bushenyi | 0.01–0.02 | – | 0.00–0.01 | 0.02–0.11 | 0.01–0.04 | |||||||

| Spring Well Water | Bushenyi | 0.01–0.03 | – | – | – | – | 0.03–0.08 | 0.15–0.75 | – | – | – | 0.05–0.39 | |

| Kitagata Hot Springs | Sheema | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.02 | 0.01–0.33 | [59] |

| Kigata Tap Water | Kabale | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.02 | – | – | 0.03–0.11 | 0.01–0.04 | [79] |

| Kacuro Tap Water | Kabale | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.02 | 0.01–0.02 | |

| Kihanga Tap Water | Kabale | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.04–0.09 | 0.02–0.04 | ||

| Kigata Tap Water | Kabale | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.02–0.18 | – | – | 0.01–0.03 | 0.03–0.08 | |

| Kanjobe Tap Water | Kabale | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.03 | 0.02–0.05 | |

| Chuho Springs | Kisoro | – | – | – | – | – | 0.72–11.2 | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.09 | [80] |

| Tap Water | Kisoro | – | – | – | – | – | 0.72–6.87 | – | – | – | – | 0.01–0.03 | |

| River Kagera | Isingiro | 0.02–0.06 | – | – | 0.01–0.04 | – | 0.02–0.08 | – | – | 0.01–0.03 | – | – | [81] |

| Eastern Uganda | |||||||||||||

| River Moyoga | Busia | 0.01–0.07 | 0.12–0.44 | 0.01–0.49 | 0.79–13.5 | 0.02–0.06 | – | – | – | – | – | – | [49] |

| Stream | Busia | – | – | 0.01–0.02 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [52] |

| Stream | Jinja | 0.01–1.98 | – | 0.01–3.93 | 0.01–2.05 | – | – | 0.01–2.13 | – | – | 0.01–2.02 | – | [57] |

| River Manafwa | Mbale | 0.02–0.10 | 0.01–0.02 | – | 0.00–0.01 | – | 0.01–0.06 | 0.01–0.03 | – | 0.01– 0.01 | 0.01–0.26 | 0.20–1.41 | [82] |

| Northern Uganda | |||||||||||||

| River Pager | Kitgum | 0.27–0.58 | 0.27–0.52 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [82] |

| Pece Stream | Gulu | 0.02–0.04 | – | – | – | – | 0.04–0.08 | 0.64–0.78 | – | – | – | – | [83,84] |

All values are reported as presented in the original studies (converted to mg/L where necessary). Reported ranges represent minimum–maximum concentrations observed across the reviewed studies and are not intended to reflect population-weighted averages. Variability in sampling design, sample size, analytical methods, and monitoring frequency across studies precluded harmonized statistical aggregation. “–” indicates values below detection limits or not reported.

4.2.1. Iron (Fe)

Iron is abundant in Ugandan groundwater, owing to the widespread occurrence of lateritic soils and ferruginous bedrock, making it one of the most prevalent metal detected in drinking-water sources [85]. Concentrations in shallow wells and springs frequently exceed the aesthetic guideline value of 0.3 mg/L, with average levels ranging from 5–11 mg/L and maxima reaching 67 mg/L in the River Rwizi catchment [78,86]. Boreholes across western and northern Uganda also show elevated Fe levels, while treated urban water supplies generally remain below 0.1 mg/L due to aeration and filtration processes [71,86]. Although iron poses minimal direct toxicity, its excess causes undesirable color, metallic taste, staining of household fixtures, and promotes iron-bacterial growth. Persistent Fe accumulation can signal co-occurrence of other redox-sensitive metals, such as Mn, and can contribute to pipe encrustation within supply networks [87,88].

4.2.2. Manganese (Mn)

Manganese commonly co-occurs with iron in groundwater under reducing conditions and is widely reported in Ugandan drinking water sources [89]. Surveys indicate that up to 30% of sampled wells exceed the 0.1 mg/L threshold, with concentrations up to 3.75 mg/L reported in protected springs in Kampala and in River Rwizi in Mbarara [77]. These elevated levels are largely attributable to natural dissolution of Mn-bearing minerals; with limited evidence of widespread anthropogenic inputs [90]. Chronic ingestion of manganese above 0.4 mg/L has been associated with neurobehavioral effects in children [91,92]. Given that most rural systems lack Mn-specific treatment, communities consuming water in the concentrations in the 1–2 mg/L range may face subtle long-term neurological risks. Effective manganese removal requires oxidation followed by filtration, as boiling does not reduce manganese concentrations [93].

4.2.3. Zinc (Zn)

Zinc is an essential trace element and is generally not harmful at the levels found in Ugandan water sources. Most sources reported Zn values below the 3–5 mg/L aesthetic taste threshold [31]. Surface waters in Bushenyi reported Zn concentrations ranging from 0.1–2.7 mg/L, likely reflecting zinc-rich soils or galvanized infrastructure [78], while rivers in Kasese District recorded higher averages of 3–9.5 mg/L [47]. Exceptionally high concentrations have been reported in the Rwakaiha (17–45 mg/L), substantially above both the WHO and UNBS guidelines [68]. In Kampala, Zn concentrations are generally low or undetectable, with isolated measurements up to 0.75 mg/L in isolated samples attributed to corrosion of galvanized pipes [44]. Bottled and rainwater sources typically contain negligible zinc. Even when slightly above the guideline, zinc poses minimal health risk; acute ingestion of a few mg/L may cause mild gastrointestinal upset (nausea, diarrhea), but homeostasis limits absorption [94,95]. Thus, zinc serves mainly as an aesthetic or corrosion indicator rather than a toxicant.

4.2.4. Copper (Cu)

Copper is another essential element, but it becomes undesirable in drinking water at concentrations above 1 mg/L due to its taste and potential for gastrointestinal irritation [96]. Most Ugandan drinking-water sources contain Cu concentrations below 0.1 mg/L unless affected by industrial or mining activity. In Kasese District, surface waters draining the Kilembe copper mine area recorded Cu levels up to 10.7 mg/L [13], and the Rwakaiha wetland recorded concentrations between 8–30 mg/L [68], far above the WHO’s 2 mg/L limit. Elevated concentrations have also been observed in tap and spring water in Kisoro, ranging from 0.72–6.87 mg/L and 0.72–11.2 mg/L, respectively [80]. These levels are associated with copper tailings and sulfide oxidation processes [97]. In contrast, Kampala’s treated municipal water typically contains less than 0.05 mg/L Cu [44]. Localized exceedances near mining areas and wetlands highlight ongoing risks from legacy waste and acid-mine drainage.

4.2.5. Lead (Pb)

Lead remains one of the most critical contaminants in Uganda’s drinking water sources due to its cumulative toxicity and absence of a safe exposure level. Many of them often exceed the 0.01 mg/L guideline. In Kampala, tap and spring waters contained Pb concentrations ranging from 0.02–0.41 mg/L [12], likely due to leaching from old leaded pipes, solder, or urban soil contamination from legacy leaded gasoline [98]. Extremely high concentrations have been reported in the River Nyamwamba, reaching up to 8.21 mg/L [18]. Additional exceedances have been documented in the River Rwizi waters (0.04–2.0 mg/L) [79], and Kalangala Bay (0.01–0.20 mg/L) [21]. These concentrations surpass the 0.01 mg/L guideline by up to 800-fold, largely from legacy leaded fuel residues, plumbing corrosion, and mining tailings [99]. Chronic exposure leads to irreversible cognitive and renal impairment, especially in children, underscoring the need for strict corrosion control and water-source monitoring [100,101].

4.2.6. Cadmium (Cd)

Cadmium, a potent nephrotoxin and human carcinogen that often co-occurs with lead in ores, battery wastes, industrial effluents, and phosphate fertilizers [102]. Although the WHO’s 0.003 mg/L guideline is stringent, reported concentrations in contaminated Ugandan waters substantially exceed this threshold. Downstream of Kilembe, the Nyamwamba River contained 0.05–1.4 mg/L Cd [13], while the Mobuku River recorded 0.12–0.44 mg/L [47]. Additional detections include 0.01–0.04 mg/L in the Rwizi River [78], and 0.01–0.52 mg/L in the Pager River Kitgum District [17]. Such contamination stems from mining waste and phosphate-fertilizer runoff [103]. Prolonged exposure primarily causes kidney damage and bone demineralization (Itai-itai disease), and it is classified as a human carcinogen [104]. Although many protected wells remain below detection limits, localized exceedances represent serious health hazards.

4.2.7. Arsenic (As)

Arsenic contamination in Uganda is geographically limited but severe near areas affected by gold mining and base-metal mining. Groundwater and spring samples from Busia and Kilembe mining regions have recorded arsenic concentrations ranging from 0.3 to 4.3 mg/L [49,52]. Surface waters such as the Mpanga and Nyamwamba rivers exhibited ranges of 0.22–4.34 mg/L and 0.01–13.8 mg/L, respectively, while the Rwakaiha Wetland recorded even higher concentrations of 8.89–25.2 mg/L, far exceeding the 0.01 mg/L WHO guideline [27,68,75]. These high values originate from the oxidation of arsenopyrite and other As-bearing minerals in copper–cobalt tailings [105]. Chronic exposure to arsenic is associated with dermatological lesions, vascular disease, and cancers of the skin, bladder, and lung [106,107]. Although contamination is geographically localized, reported concentrations rank among the highest in East Africa and pose serious carcinogenic risks to affected communities.

4.2.8. Chromium (Cr)

Chromium occurs in drinking water primarily as trivalent Cr(III) and hexavalent Cr(VI), with total chromium guideline values set at 0.05 mg/L [108]. In most Ugandan water sources, chromium levels are low (often undetectable < 0.01 mg/L), except near industrial and mining zones. Streams adjacent to the steel industries in Jinja contained chromium levels of 0.01–2.05 mg/L [57], which is above the limit and indicative of industrial discharge. Wetlands and surface waters receiving urban runoff around Kampala reported concentrations of 0.01–0.09 mg/L [25], confirming untreated effluent inflow. However, more severe enrichment occurs in mining-affected environments, including the Mobuku and Nyamwamba rivers (0.79–13.5 mg/L) and (1.05–3.10 mg/L), respectively, and the Rwakaiha Wetland (38.2–148 mg/L) [68]. These concentrations point to chromium-bearing effluents from urban runoffs, tanneries, and metalworks. Although Cr contamination is less widespread than Pb or Cd, the presence of carcinogenic Cr(VI) in such hotspots constitutes a major health hazard and underscores the urgent need for effluent control and continuous monitoring.

4.2.9. Mercury (Hg)

Mercury contamination in Ugandan drinking water is relatively uncommon outside artisanal gold mining sites. Routine monitoring in urban areas finds mercury at or below detection limits; for example, Kampala tap and spring water samples have shown concentrations between 0.01 and 0.04 mg/L [44,109]. These values approach the parametric value established under the European Union Drinking Water Directive (EU 2023/2184) and U.S. EPA National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) (0.001 mg/L), but remain below the WHO limit of 0.006 mg/L. The primary concern is in gold mining districts such as Busia and Karamoja, where mercury is used for amalgamation. Streams near mining camps have been found to contain Hg on the order of 0.02–0.06 mg/L [19,49], indicating runoff of mercury from processing sites. Mercury is extremely neurotoxic to the nervous system, and even low levels can bioaccumulate as methylmercury in aquatic food chains (especially if converted to methylmercury in aquatic food chains) [110]. Given the absence of major industrial mercury sources in Uganda, contamination remains localized to artisanal mining zones.

4.2.10. Nickel (Ni)

Nickel concentrations in Ugandan drinking water sources are generally low but can exceed guideline values due to corrosion or specific mineral sources. The national drinking water standard for Ni in Uganda (US EAS 12:2014) is 0.02 mg/L, while the WHO guideline value is 0.07 mg/L [29,30]. In one survey of Kampala’s water, tap water samples reported Ni concentrations up to 0.17 mg/L Ni [44], likely resulting from leaching from nickel-plated components or stainless steel parts in the distribution system. In Kasese, rivers and streams near and downstream the mines recorded Ni levels ranging from 0.07–12 mg/L [13,14,75], attributed to nickel-bearing ores and tailings. While nickel is an essential element required in trace amounts, chronic exposure to elevated nickel concentrations in drinking water may cause dermatitis, allergic reactions, and potentially renal or reproductive effects [111]. All reported concentrations exceeding 0.02 mg/L surpass the national standard and warrant attention.

4.2.11. Cobalt (Co)

Cobalt lacks a formal WHO drinking-water guideline value, but it is of interest in Uganda due to cobalt-rich mineralization associated with copper mining. The classic case is Kilembe in Kasese District, where decades of copper-cobalt mining left waste rich in cobalt [112]. Local groundwaters in the Kilembe valley recorded Co concentrations up to 3.9 mg/L [13], whereas uncontaminated sources typically remain below 0.1 mg/L. River Nyamwamba reported Co concentrations ranging from 0.01–0.25 mg/L and Rwakaiha Wetland (17–45.6 mg/L), reflecting leaching of copper–cobalt tailings [68]. Although cobalt is an essential part of Vitamin B12, ingesting it at mg/L concentrations could lead to health issues such as cardiomyopathy or thyroid dysfunction [113]. Outside mining regions, cobalt is rarely detected in water. The highly localized nature of Co pollution means targeted solutions are feasible. Its pollution is highly localized, making targeted remediation feasible through constructed wetlands or adsorption-based filters.

4.3. PTE Pollution and Health Risk Implications

PTEs in drinking water present both acute and chronic health risks (Table 4), with chronic low-dose exposure being the primary concern in Uganda. The toxicological impact depends on the specific metal, its concentration, duration of exposure, and the vulnerability of the exposed population [114]. While trace elements like Fe, Zn, Cu, Cr(III), Mn, and Co are needed in small amounts for normal physiological functions, they become harmful when concentrations exceed biological tolerance thresholds [115]. Conversely, non-essential metals, including Pb, Cd, Hg, and As, have no known beneficial role in human metabolism and exhibit toxicity even at very low concentrations.

Lead remains one of the most neurotoxic contaminants and poses particular risks to children, in whom exposure is associated with impaired neurological development, while adults may experience hypertension and renal dysfunction [116]. Cadmium primarily targets the kidneys and the skeletal system [117], arsenic exposure leads to skin lesions and multiple cancers [118], and mercury targets the nervous system and kidneys [119]. Among essential metals, excess Cu and Zn are associated with gastrointestinal distress and organ damage at high levels [120], whereas prolonged Mn exposure has been associated with neurotoxicity resembling Parkinsonian symptoms [121]. These adverse effects justify the stringent health-based guideline values for metals in drinking water by international and national regulatory agencies [29,30,31].

Epidemiological evidence from Uganda substantiate these health concerns. For instance, in Kampala, children exposed to spring or tap water contaminated with Pb were found to have elevated blood-lead levels and associated cognitive impairments [60]. Communities in Kasese District, situated downstream from the Kilembe mine, report increased prevalence of hepatic and renal dysfunction plausibly linked to long-term exposure to Co, Cu, and Pb in drinking water [48,122]. Although comprehensive nationwide health surveillance data remain inadequate, these localized findings suggest that there is a measurable public health burden attributable to PTE pollution. Evidence from peri-urban Kampala further supports these concerns, where elevated concentrations of Cu, Cd, Cr, Pb, and Zn in soils and food crops within the Luzira Industrial Area were associated with industrial activity and potential human health risks through environmental exposure pathways [123]. Although a formal hazard quotient or quantitative non-carcinogenic risk assessment was not conducted due to inconsistent exposure assumptions across studies, many reported concentrations exceed health-based guideline values by substantial margins, indicating clear potential for both non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic health risks.

Health risks are further amplified by the frequent co-occurrence of multiple PTEs within the same water sources, which may result in additive or synergistic toxic effects. For example, combined Pb and Mn exposure has been shown to intensify neurodevelopmental impairments beyond the individual effects of each metal [124], while interactions between As and Cd enhance carcinogenicity [125]. Such mixture toxicity is particularly relevant in informal settlements and mining zones where water sources are unregulated and commonly shared.

Vulnerable populations, including infants, children, pregnant women, the elderly, and those with pre-existing illnesses, bear the highest risks. Children, for instance, can absorb ingested Pb at rates significantly higher than adults, and prenatal exposure to Pb, Cd, or Hg has been associated with fetal development abnormalities [126]. Overall, measured concentrations of Pb, Cd, As, Hg, Cr, and Mn in Ugandan water supplies are sufficient to cause long-term neurological, renal, hepatic, and carcinogenic outcomes. The combined effect of multi-metal exposure and population vulnerability underscores the urgency for national mitigation and monitoring frameworks.

Table 4.

Key health effects of PTE exposure through drinking water.

Table 4.

Key health effects of PTE exposure through drinking water.

| Heavy Metal | Primary Health Effects (from Water Exposure) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Pb | Neurodevelopmental impairment in children; hypertension and renal damage in adults | [127] |

| Cd | Kidney dysfunction; bone demineralization (itai-itai syndrome); gastrointestinal irritation; lung carcinogenicity | [128] |

| As | Skin lesions; vascular disease; cancers of skin, bladder, and lung | [129] |

| Hg | Neurological damage (tremors, cognitive deficits); renal impairment; fetal neurotoxicity | [130] |

| Cr | Carcinogenic (stomach, lung); hepatic and renal damage; gastrointestinal ulcers | [131] |

| Cu | Gastrointestinal irritation; at high doses, hepatic injury | [132] |

| Zn | Low toxicity overall; excess causes nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea | [133] |

| Ni | Allergic dermatitis; respiratory effects; renal and reproductive toxicity | [112] |

| Co | Cardiomyopathy and thyroid dysfunction at high levels; affect hematopoiesis | [134] |

| Mn | Cognitive impairment in children; Parkinson-like symptoms in adults | [135] |

| Fe * | Liver damage in hemochromatosis patients; primarily an aesthetic concern in drinking water | [136] |

* Fe is primarily an esthetic or operational concern in water; direct toxic effects occur only in genetically susceptible individuals or at extremely high intake levels.

4.4. Water Quality Regulations and Monitoring in Uganda

Uganda’s regulatory framework for drinking-water safety is comprehensive and broadly aligned with international and regional standards. The legal foundation for water resources protection and pollution control is established under the Water Act, Cap 152 (1997); An Act to provide for the Use, Protection and Management of Water Resources together with the National Environment Act, No.5 (2019); an act to provide for sustainable management of the environment. These laws assign overall responsibility for water resources protection and pollution control to the Ministry of Water and Environment (MWE), implemented through the Directorate of Water Resources Management [137,138]. The NWSC is mandated to supply safe water and sanitation services in urban areas [137], while the UNBS establishes legally binding drinking water quality specifications, most notably US EAS 12:2014; Potable Water—Specification [30]. These national standards closely align with those of the WHO and East African Community (EAC) benchmarks and specify permissible limits for PTEs such as Pb (0.01 mg/L), Cd (0.003 mg/L), As (0.01 mg/L), Cr (0.05 mg/L), Hg (0.006 mg/L), with secondary esthetic thresholds for Fe (0.3 mg/L) and Mn (0.4 mg/L) [139].

Complementary laws further reinforce this statutory architecture. The Constitution of the Republic of Uganda (1995) guarantees the right to a clean and healthy environment under Article 39, providing the legal foundation for the protection of drinking water quality [140]. The Public Health Act, Cap. 281 (1935, revised) empowers local health authorities to prevent the distribution of unsafe water and to institute corrective measures where risks to public health are identified [141]. Industrial and mining discharges are regulated under the National Environment (Standards for Discharge of Effluent into Water or on Land) Regulations (2020), which establish maximum permissible concentrations PTEs in effluents, including Pb 0.1 mg/L, Cd 0.05 mg/L, As 0.1 mg/L, Cr 2 mg/L, Hg 0.005 mg/L [142]. At the local level, the Local Government Act, Cap. 243 (1997); An Act to provide for Decentralization and Devolution of Functions, Powers and Services to Local Governments, assigns responsibilities for rural water supply management and basic water quality monitoring to District Water Offices, operating under the supervision of MWE and the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA).

Despite this relatively comprehensive legislative framework, gaps in implementation and routine surveillance remain. Water supplied through NWSC-operated systems is subject to regular operational monitoring and generally complies with chemical standards at the treatment-plant level. However, the majority of Uganda’s population, particularly in rural and peri-urban areas, depend on self-supply and informal sources such as boreholes, springs, shallow wells, and surface waters. These decentralized sources lie outside continuous national drinking water monitoring and are only intermittently assessed through project-based studies or targeted investigations. As a result, several districts, especially in northern and eastern Uganda, remain underrepresented in trace-metal monitoring, particularly for informal and self-supply water sources. Trace metals are therefore seldom analyzed at the point of use, owing to constraints in laboratory capacity, logistical barriers, and sustained financing. Consequently, chemical contamination from both natural geochemical and localized anthropogenic activities may therefore remain undetected for extended periods.

Similar challenges affect the regulation of industrial and mining effluents. Although discharge-permitting frameworks exist, enforcement capacity is uneven, particularly among small-scale industries and artisanal mining operations. Routine compliance monitoring, independent audits, and public reporting of violations remain limited, and available data are often fragmented or inaccessible [143]. Persistent contamination linked to mine tailings and waste discharges in districts such as Kasese and Busia illustrates how regulatory and monitoring gaps can translate into prolonged PTE exposure for downstream communities.

Strengthening water-quality governance in Uganda requires a coordinated, multi-level approach. Expanding trace-metal analytical capacity, particularly within district-level and regional laboratories, would enhance early detection of contamination and support risk management. Regular surveillance must also extend beyond formal piped systems to include informal and self-supply water sources that serve vulnerable populations. Furthermore, enhanced coordination among MWE, UNBS, NWSC, and NEMA is also needed to harmonize monitoring protocols, align inspection schedules, and establish centralized water-quality data repositories. Ultimately, translating policy into effective protection will depend on sustained investment in enforcement mechanisms, personnel training, and transparent public accountability. Only then can Uganda achieve consistent compliance with its own national standards and the broader health-based international guidelines.

4.5. Treatment and Mitigation Strategies

Mitigating PTE contamination in Uganda’s drinking water requires a combination of both centralized and decentralized treatment approaches tailored to local hydrogeological conditions, contamination profiles, and resource availability. In areas supplied by the NWSC, conventional water-treatment plants provide the primary barrier against metal contamination. These systems typically employ coagulation–flocculation, sedimentation, filtration, and disinfection, which are effective for removing particulate-bound metals and metals associated with suspended solids [144]. Process optimization, including pH adjustment and lime addition, can further enhance the precipitation and removal of metals such as Pb, Cd, and Cu as hydroxides [145], while aeration and oxidation remain highly effective, particularly for Fe and Mn removal (often achieving reductions of more than 90% reductions) [146].

Metals that persist predominantly in dissolved form, particularly As and hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)), require advanced treatment processes. At the utility scale, adsorption using iron-oxide-coated media or activated alumina, as well as ion-exchange processes, have demonstrated high removal efficiencies for these contaminants [147]. Membrane technologies such as nanofiltration and reverse osmosis are capable of achieving near-complete removal of dissolved metals; however, their application in Uganda remains limited to specialized settings due to high capital and operational costs, the need for skilled maintenance, and challenges associated with concentrate and brine-waste management [148].

In rural and peri-urban areas, simpler and lower-cost treatment options are often preferred. Aeration followed by sand or catalytic filtration is commonly applied at boreholes to control iron and manganese [149]. Locally sourced adsorbents like bone char and biochar derived from agricultural-waste residues have demonstrated high sorption affinity for As and Pb and are increasingly incorporated into household and community-scale filtration units [150]. In mining-impacted catchments such as Kasese and Busia, mitigation has included lime dosing, sedimentation ponds, and constructed wetlands to attenuate metal loads before water reaches downstream users [151]. While these nature-based systems are cost-effective and contextually appropriate, they are generally insufficient as standalone solutions for meeting drinking water standards.

At the household level, point-of-use (POU) technologies play an important role in reducing exposure where centralized treatment is unavailable. Biosand filters embedded with iron-coated sand or charcoal, as well as ceramic pot filters impregnated with metal-adsorbing materials, offer dual benefits of microbial and PTE removal [152,153]. In contrast, boiling remains ineffective for PTE removal and may increase metal concentrations through water loss during evaporation [154]. Effective mitigation, therefore, depends on matching treatment options to contaminant type, concentration, and system scale. In practice, sequential or combined treatment trains are often required to achieve compliance with health-based drinking water guidelines. A comparative overview of heavy-metal treatment technologies and their applicability within the Ugandan context is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparative performance and contextual suitability of PTE removal technologies for drinking water systems in Uganda.

While several of the discussed treatment technologies are widely applied globally, many, such as aeration–filtration, coagulation–filtration, and adsorption using biochar or iron-based media, are already implemented in Uganda at household, community, or utility scales. More advanced systems, including ion exchange and membrane filtration, remain largely confined to institutional or site-specific applications due to cost and operational constraints, and maintenance requirements. Reported removal efficiencies are therefore approximate and may vary based on influent characteristics, pH, temperature, and system design. In practice, combined or sequential treatment trains are often necessary to meet compliance with WHO and other health-based drinking-water guideline values.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review demonstrates that contamination of drinking water by potentially toxic elements remains a widespread and persistent challenge across Uganda. Elevated concentrations of Pb, Cd, As, Mn, Fe, and, in certain locations, Cr and Hg, are consistently reported in groundwater, surface waters, and informal drinking water supplies, particularly in mining-impacted districts, urban informal settlements, and rapidly industrializing catchments. These exceedances frequently exceed both WHO guideline values and national standards, highlighting sustained risks to public health.

The associated health implications are substantial: chronic low-dose exposure to PTEs poses risks to neurological development, renal and cardiovascular function, and long-term carcinogenic outcomes, with children, pregnant women, and communities reliant on unregulated or poorly protected water sources facing disproportionate vulnerability. The frequent co-occurrence of multiple metals in the same water sources further amplifies health risks through potential synergistic toxic effects.

Despite Uganda’s well-developed legal and institutional frameworks for drinking water-quality protection, this review identifies persistent gaps in implementation, routine monitoring, and data accessibility. Current monitoring efforts remain largely focused on formal piped systems, while the majority of rural and peri-urban populations depend on self-supply sources that fall outside continuous regulatory oversight. Limitations in laboratory capacity, logistical constraints, and sustained financing further constrain routine trace-metal testing at the point of use.

Reducing exposure to PTEs in Uganda will require a coordinated, multi-level strategy that integrates governance, infrastructure, and context-appropriate treatment solutions. At the utility level, strengthening pollution control, upgrading aging distribution infrastructure, and optimizing treatment processes, including corrosion control and targeted metal removal, are essential. In rural and peri-urban settings, low-cost and decentralized interventions such as aeration–filtration, adsorption media, and point-of-use filtration systems offer practical pathways for exposure reduction, provided that socio-economic constraints, maintenance capacity, and community acceptance are explicitly addressed.

Ultimately, safeguarding drinking-water quality in Uganda will depend on sustained investment in monitoring capacity, regulatory enforcement, and equitable access to appropriate treatment technologies. Addressing PTE contamination is therefore not only a technical challenge but also a governance and public-health priority. Progress in this area is essential for ensuring genuinely safe drinking water and for advancing Uganda’s commitment to Sustainable Development Goal 6 beyond access metrics toward long-term water safety and health protection.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pollutants6010009/s1, The completed PRISMA 2020 Abstract Checklist, PRISMA 2020 Full Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B. (Gabson Baguma), G.B. (Gadson Bamanya); A.G., H.T. and R.N.; methodology, G.B. (Gabson Baguma), G.B. (Gadson Bamanya) and A.G.; software, G.B. (Gabson Baguma) and W.A.; validation, G.B. (Gadson Bamanya), I.B. and W.W.; formal analysis, G.B. (Gabson Baguma), G.B. (Gadson Bamanya), W.W., I.B. and W.A.; investigation, G.B. (Gabson Baguma), G.B. (Gadson Bamanya) and R.N.; data curation, G.B. (Gabson Baguma), G.B. (Gadson Bamanya), W.A. and R.N.; writing—original draft preparation, G.B. (Gabson Baguma), H.T., R.N. and A.G.; writing— review and editing, G.B. (Gabson Baguma), G.B. (Gadson Bamanya), A.G., I.B. and W.W.; visualization, G.B. (Gabson Baguma) and G.B. (Gabson Baguma); supervision, H.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the conclusions of this study are available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Wilber Waibale was employed by the institution Uganda Industrial Research Institute. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). National Population and Housing Census 2024-Final Report; UBOS: Kampala, Uganda, 2024. Available online: https://statistics.ubos.org/nphc/reports/National-Population-and-Housing-Census-2024-Final-Report-Volume-1-Main.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Ministry of Water and Environment (MWE). Water and Environment Sector Performance Report 2020; MWE: Kampala, Uganda, 2020; p. 279.

- Schmoll, O.; Howard, G.; Chorus, I. Protecting Groundwater for Health: Managing the Quality of Drinking-Water Sources; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Water Intelligence Online; Volume 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaanah, P.; Mothapo, R.A. Sustainability of drinking water and sanitation delivery systems in rural communities of the Lepelle Nkumpi Local Municipality, South Africa. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baguma, G.; Bamanya, G.; Gonzaga, A.; Ampaire, W.; Onen, P. A Systematic Review of Contaminants of Concern in Uganda: Occurrence, Sources, Potential Risks, and Removal Strategies. Pollutants 2023, 3, 544–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baguma, G.; Musasizi, A.; Twinomuhwezi, H.; Gonzaga, A.; Nakiguli, C.K.; Onen, P.; Angiro, C.; Okwir, A.; Opio, B.; Otema, T.; et al. Heavy Metal Contamination of Sediments from an Exoreic African Great Lakes’ Shores (Port Bell, Lake Victoria), Uganda. Pollutants 2022, 2, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, D.; Słowik, J.; Chilicka, K. Review heavy metals and human health: Possible exposure pathways and the competition for protein binding sites. Molecules 2021, 26, 6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Tareq, A.M.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Khusro, A.; Idris, A.M.; Khandaker, M.U.; Osman, H.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; et al. Impact of heavy metals on the environment and human health: Novel therapeutic insights to counter the toxicity. J. King Saud Univ.—Sci. 2022, 34, 101865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN-Water). SDG6 Synthesis Report 2018 on Water and Sanitation; UN-Water: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; 199p, Available online: https://www.unwater.org/publications/sdg-6-synthesis-report-2018-water-and-sanitation (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). GOAL 6: Clean Water and Sanitation. UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. Available online: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/sustainable-development-goals/why-do-sustainable-development-goals-matter/goal-6 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Sanusi, I.O.; Olutona, G.O.; Wawata, I.G.; Onohuean, H. Heavy metals pollution, distribution and associated human health risks in groundwater and surface water: A case of Kampala and Mbarara districts, Uganda. Discov. Water 2024, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasozi, K.I.; Namubiru, S.; Kamugisha, R.; Eze, E.D.; Tayebwa, D.S.; Ssempijja, F.; Okpanachi, A.O.; Kinyi, H.W.; Atusiimirwe, J.K.; Suubo, J.; et al. Safety of Drinking Water from Primary Water Sources and Implications for the General Public in Uganda. J. Environ. Public Health 2019, 2019, 7813962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.R.; Susan, T.B. Water contamination with heavy metals and trace elements from Kilembe copper mine and tailing sites in Western Uganda; implications for domestic water quality. Chemosphere 2017, 169, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owor, M.; Hartwig, T.; Muwanga, A.; Zachmann, D.; Pohl, W. Impact of tailings from the Kilembe copper mining district on Lake George, Uganda. Environ. Geol. 2007, 51, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esdaile, L.J.; Chalker, J.M. The Mercury Problem in Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining. Chem.—A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 6905–6916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulenga, M.; Ouma, K.O.; Monde, C.; Syampungani, S. Aquatic Mercury Pollution from Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining in Sub-Saharan Africa: Status, Impacts, and Interventions. Water 2024, 16, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Li, B.; Cao, X.; Huang, J.; Long, E.; Wu, P. Geochemical process of arsenic source and fate in water environment of karst gold mining region, Southwestern China. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 38, 104159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.C.d.S.; Hott, R.d.C.; Santos, M.J.d.; Santos, M.S.; Andrade, T.G.; Bomfeti, C.A.; Rocha, B.A.; Barbosa, F.; Rodrigues, J.L. Arsenic in Mining Areas: Environmental Contamination Routes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omara, T.; Karungi, S.; Kalukusu, R.; Nakabuye, B.V.; Kagoya, S.; Musau, B. Mercuric pollution of surface water, superficial sediments, Nile tilapia (Oreochromis nilotica Linnaeus 1758 [Cichlidae]) and yams (Dioscorea alata) in auriferous areas of Namukombe stream, Syanyonja, Busia, Uganda. PeerJ 2019, 2019, e7919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, S.; Wijesekara, H.; Ireshika, A.; Zhang, T.; Pu, M.; Petruzzelli, G.; Pedron, F.; Hou, D.; Wang, L.; Zhou, S.; et al. Tungsten contamination, behavior and remediation in complex environmental settings. Environ. Int. 2023, 181, 108276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljung, K.; Otabbong, E.; Ander, J.A. Heavy Metal Discharge into Lake Victoria—A Study of the Ugandan Cities of Kampala, Jinja and Entebbe. Master’s Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mbabazi, J.; Kwetegyeka, J.; Ntale, M.; Wasswa, J. Ineffectiveness of Nakivubo wetland in filtering out heavy metals from untreated Kampala urban effluent prior to discharge into Lake Victoria, Uganda. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 5, 3431–3439. [Google Scholar]