Abstract

Unsafe disposal of pesticide waste remains a critical environmental and public health issue in developing agricultural systems. This study examined cocoa farmers’ disposal behaviours and their determinants across Nigeria’s major cocoa-producing regions using an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design. Quantitative data were collected from 391 farmers, followed by 23 in-depth interviews to contextualise behavioural drivers. Results showed that knowledge of pesticide risks and availability of disposal facilities significantly predicted safer disposal practices (R2 = 0.469, p < 0.05), whereas age had a negative influence. Qualitative findings revealed that negative attitudes, social norms, and limited infrastructure reinforced unsafe behaviours, while membership in farmers’ associations promoted safer practices through peer learning. A joint display demonstrated convergence between structural enablers (collection cages, extension support) and behavioural factors (knowledge, attitudes, norms). The study identifies a dual challenge of systemic shortcomings and behavioural inertia, suggesting that regulatory action alone is insufficient without farmer engagement and education. Policy and extension programmes should prioritise collection infrastructure, association-based training, and Integrated Pest Management to promote sustainable pesticide waste management. These insights advance understanding of pesticide disposal behaviour and offer actionable guidance for environmental governance in low- and middle-income agricultural contexts.

1. Introduction

The relevance of agriculture cannot be downplayed. It plays a pivotal role in human life across various aspects and in the global environment [1]. Unsafe pesticide use is a concern in developing nations, where farmers perceive pesticides as an effective and reliable “medicine” to combat pests and diseases. Pesticide use in Nigeria’s agricultural sector has steadily increased since its introduction in the 1950s, mainly in response to population growth and the expanding need for food production [2]. In this regard, environmental and health risks have been associated with pesticide use [3], yet farmers have often neglected these concerns. There are concerns about the effects of pesticides on non-target organisms, as most pesticides used enter non-target environments, thereby altering ecosystems and, consequently, agricultural productivity [4]. One of the challenging problems in pesticide use is the management of waste [5], which is a crucial step. Additionally, due to their widespread use and high risks, pesticide waste is one of the most pressing agro-environmental problems [5]. A more effective environmental control strategy is imperative to address environmental pollution resulting from pesticide waste. Pesticide waste is categorised as, but not limited to, empty containers, surplus pesticide formulations, excess concentrated products, rinse water generated from cleaning containers and application equipment, and materials used in managing spills and leaks [6].

A significant number of farmers remain unaware that pesticide waste should not be disposed of in water bodies or composted on farmland [7], especially in developing nations where regulations or guidelines for proper disposal methods are ineffective, and many farmers are uneducated. Although some farmers retain empty pesticide containers due to their heavy reliance on pesticide use, this practice has led to the accumulation of waste across all stages of pesticide handling [8].

Pesticide containers are often manufactured as “one-way” packaging, meaning they are not intended for reuse [6]. These containers frequently remain heavily contaminated, posing serious risks to both human health and the environment. However, some farmers reuse empty pesticide containers for other purposes, such as domestic activities [9]. The improper disposal of pesticide rinsates is common in developing countries [10]. As a result, pesticide contamination has affected both surface and groundwater, threatening the quality and safety of available drinking water supplies [11].

One major pathway of point-source pollution of water and soil in agricultural areas is the unsafe disposal of pesticide waste. The uncontrolled release of pesticide wastes is dangerous to both people and the environment. For instance, pesticide-polluted water is harmful to aquatic organisms and humans. Waste generation is an unavoidable aspect of pesticide-based farming operations and is inherently tied to modern agricultural practices [12]. In principle, reducing reliance on hazardous agrochemicals through organic, agroecological, or other low-input systems can substantially decrease pesticide waste and associated risks, provided such transitions are agronomically and economically feasible. However, for many smallholders in developing countries, including Nigeria, pesticides remain integral to managing severe pest and disease pressure and sustaining yields [2,3,4]. A more pragmatic environmental control strategy, therefore, combines (i) safer product choice and integrated pest management (IPM), (ii) precision dosing and proper sprayer calibration to minimise leftovers, and (iii) environmentally sound disposal of unavoidable wastes. Previous studies have shown that the disposal of pesticide waste (empty pesticide containers and pesticide rinsates) is a significant challenge in pesticide usage [6,13,14]. Previous studies have shown that the disposal of pesticide waste (empty pesticide containers and pesticide rinsates) is a significant challenge in pesticide usage [6,13,14].

In Nigeria, pesticide use has increased rapidly without parallel improvements in safe handling and post-use management. Between 2010 and 2022, national pesticide imports rose to approximately 19,000 tonnes annually, dominated by herbicides (over 60% of total volume), followed by insecticides and fungicides applied on cocoa, maize, and vegetable crops [2]. Weak enforcement of hazardous waste policies, low literacy levels, and limited extension support have exacerbated unsafe disposal practices. Although Nigeria’s Harmful Wastes (Special Criminal Provisions) Act (1988) and National Environmental (Chemicals, Pharmaceuticals, Soap and Detergent Manufacturing) Regulation (2009) mention hazardous waste, they lack clear operational guidance on pesticide packaging and recycling. NAFDAC regulates registration and importation, but not post-consumer collection, and no national take-back or Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) system exists. Agricultural extension services rarely address pesticide waste. These are systemic barriers—regulatory, infrastructural, and institutional—whereas individual practices such as reuse of containers or disposal in streams reflect behavioural factors like attitudes, norms, and risk perception.

Cocoa farming is one of the key agricultural activities in Nigeria. The country ranks among the top six global cocoa producers, with approximately fourteen of its thirty-six states actively engaged in cocoa cultivation, underscoring the significance of Cocoa in Nigeria’s economy both pre- and post-independence [15]. Pests are a major challenge facing cocoa production in Nigeria, leading cocoa farmers to rely heavily on pesticides [16]. Cocoa is cultivated across approximately 14 states, with recurrent pressures from capsid pests and black pod disease, which drive reliance on insecticides, fungicides, and herbicides for understorey management [15,16]. Applications typically coincide with peak disease and pest periods during the rainy season. They are delivered via knapsack sprayers to smallholder plots; this practice generates leftover spray solutions, rinsates, and empty containers [16]. In the absence of reliable collection or take-back mechanisms, these streams often enter farms and nearby waterways, aligning with regional evidence on unsafe post-application practices and disposal in West African cocoa systems [17] and are consistent with broader environmental and health concerns documented for pesticide use [3,4,11].

Prior work links farmers’ pesticide behaviours to attitudes, perceived norms, and control beliefs, often operationalised through the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) and related behavioural lenses [13,18,19,20]. These approaches are powerful but typically rely on cross-sectional surveys, which can under-specify contextual mechanisms (e.g., local norms, association dynamics, practical constraints in waste handling) [13,21,22]. Our explanatory sequential mixed-methods design strengthens inference by (i) quantifying relationships between knowledge, facilities, sociodemographics, and disposal practices, then (ii) qualitatively unpacking how and why attitudes, social norms, and association membership influence behaviour in situ [19,21]. This integrated design clarifies where systemic barriers (e.g., lack of facilities) end and behavioural drivers (e.g., attitudes and norms) begin, thereby sharpening targets for policy and extension.

Building on this context, the study pursues three objectives: (i) to describe current pesticide waste disposal practices among cocoa farmers across Nigeria’s major producing regions; (ii) to identify determinants of disposal behaviour, focusing on knowledge, access to disposal facilities, age, and other sociodemographic factors; and (iii) to explain how contextual factors (e.g., norms, association membership) shape practices. We hypothesised that H1—higher knowledge of pesticide risks is associated with safer disposal practices [13]; H2—availability of disposal facilities is positively associated with safer disposal practices [23,24,25,26]; and H3—older age is negatively associated with safer disposal practices (consistent with prior behavioural findings) [23]. In this study, the term disposal facilities (hereafter referred to as collection facilities) refers to any designated infrastructure for the safe return, storage, or aggregation of used pesticide containers, including metal cages, bins, or central drop-off points managed by cooperatives, agro-dealers, or local authorities.

It is essential to understand the factors that influence how farmers dispose of pesticide waste, particularly in cocoa production. However, there is limited information on this kind of study in Nigeria. A few studies have examined pesticide waste disposal, and most have employed a quantitative approach or focused on a specific region in Nigeria [8,15,16,17,18]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, none of these studies has explored the determinants of farmers’ disposal behaviour using a mixed-methods approach in Cocoa farming. Using this design enables the enrichment of quantitative data through qualitative inquiry (e.g., in-depth interviews). Moreover, this method enables the collection of both rich contextual information and measurable data, resulting in a more detailed and comprehensive understanding of complex issues [19,22]. Therefore, this study examines cocoa farmers’ disposal practices and their determinants in Nigeria.

2. Materials and Methods

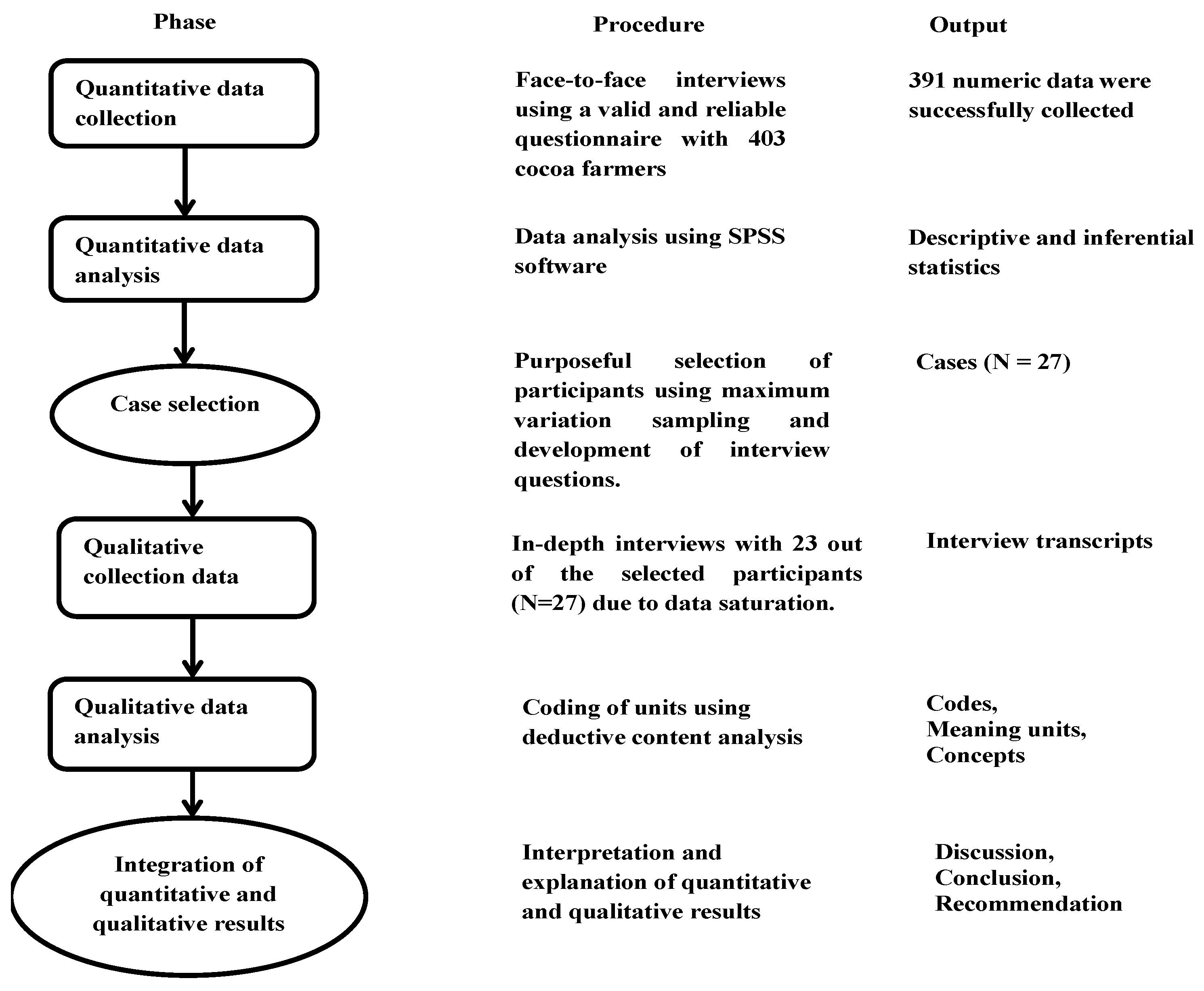

2.1. Study Design

The current study utilises a mixed methods design. The explanatory sequential approach is a two-stage mixed-methods design that involves collecting numeric data followed by in-depth interviews to enhance the quantitative results. This is because quantitative methods alone would not be enough to explain the determinants of farmers’ disposal behaviours. Qualitative data were collected based on farmers’ disposal-behaviour scores in the questionnaire. This mixed-methods framework allowed the researchers first to identify statistical relationships between key predictors (knowledge, age, access to collection facilities) and disposal behaviour, and then use qualitative inquiry to understand the contextual meanings of these relationships. The quantitative phase provided the basis for participant selection in the qualitative phase, ensuring complementarity and explanatory depth.

2.2. Study Area

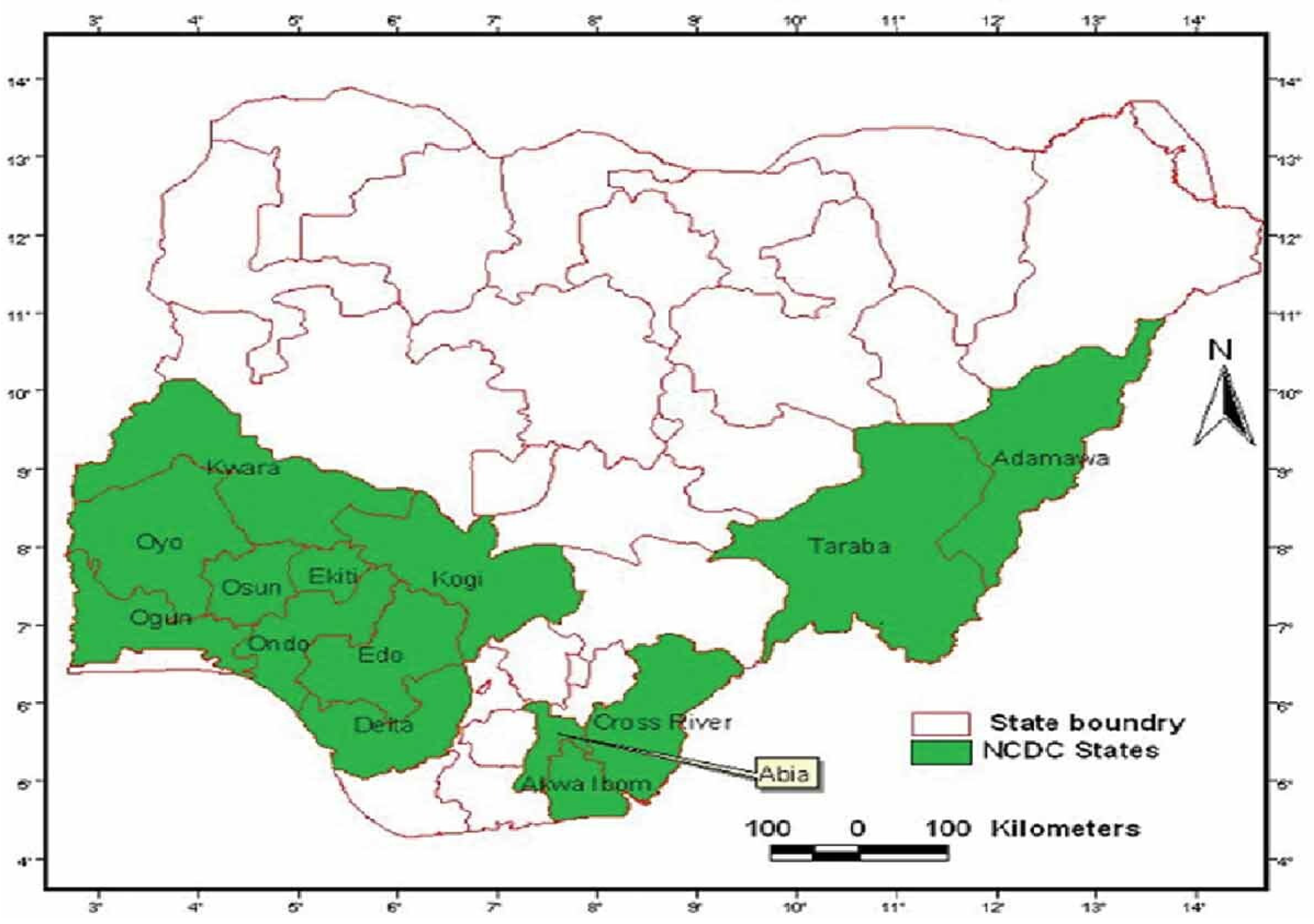

Cocoa production in Nigeria is concentrated in approximately fourteen cocoa-producing states across three main geographical cocoa belts: the South-West, South-East, and North-Central regions. The South-West remains the dominant production zone, led by Ondo and Osun States, followed by Oyo, Ogun and Ekiti. Cross River State is the principal cocoa producer in the South-East, while Kogi represents the main producing state in the North-Central belt. This study was conducted in four of the highest-producing states across these three belts: Ondo and Osun (South-West), Cross River (South-East) and Kogi (North-Central). These states were selected to reflect the ecological and institutional diversity of Nigeria’s cocoa sector, ranging from long-established cocoa landscapes in the humid forest belt to emerging cocoa expansion areas further north. A map of the study area is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Map showing cocoa-producing states in Nigeria [27].

2.3. Sample Size and Data Collection

The quantitative and qualitative sample sizes and data collection procedures followed those previously applied in related studies [20,21]. A cross-sectional design was used for the quantitative phase, while semi-structured, in-depth interviews were undertaken in the qualitative phase. In total, 391 cocoa farmers participated in the survey, and 23 farmers were interviewed.

Data were collected across the four states described in Section 2.2. Within each state, three to four cocoa-farming communities were selected in consultation with state agricultural extension offices and farmer associations. The sampling frame comprised registered cocoa farmers listed by state cocoa development units. Farmers were eligible to participate if they adhered to the following criteria:

- (i)

- had cultivated cocoa for at least five years;

- (ii)

- personally handled or supervised pesticide application; and

- (iii)

- provided informed consent.

We used multistage sampling to select participants for the quantitative phase, ensuring proportional representation across regions (Figure 2). After administering the questionnaires, individual farmers were scored on a composite “disposal behaviour” index (explained in Section 2.3). Participants were then grouped into categories of safe, intermediate, or unsafe disposal practices. Using maximum variation sampling, we purposefully selected nine farmers from each region—representing diversity in age, education, and farm size—for the qualitative phase. Of the 27 selected, 23 were successfully interviewed before data saturation was reached. The sample of 391 farmers reflects the regional distribution of cocoa production, while the 23 qualitative participants capture heterogeneity across gender, age group, education level, and farm size. This design ensured representativeness in behavioural patterns while maintaining depth in qualitative insight.

Figure 2.

Sequential explanatory mixed-methods design of the study.

2.4. Measures

Based on previous studies, we developed a disposal practices questionnaire (10 items) informed by validated instruments [23,24,25,26]. The other sections of the questionnaire assessed farmers’ sociodemographic characteristics (13 items) and pesticide waste knowledge (10 items). To maximise response accuracy among respondents with low literacy levels, questionnaires were administered verbally through face-to-face interviews in the local language. The quantitative data were also used to screen participants for inclusion in the qualitative phase. The questionnaire comprised the following sections:

- (a)

- Disposal practices (10 items) assessed behaviours such as re-application of leftover spray solution, storage of leftovers, disposal of rinse water, burning or burying empty containers, reuse for domestic purposes, and disposal in streams or canals.

- (b)

- Knowledge of pesticide wastes (10 items) assessed awareness of pesticide toxicity, residual contamination in containers, recommended rinsing procedures, and potential environmental impacts (examples shown in Table 1).

- (c)

- Sociodemographic factors (13 items) included age, gender, level of education, farming experience, farm size, access to extension services, prior training, and availability of protective equipment. A complete list of questionnaire items is provided in Supplementary Material Table S1.

Table 1.

Knowledge of pesticide waste disposal among the farmers.

Table 1.

Knowledge of pesticide waste disposal among the farmers.

| Knowledge of Pesticide Risks from Waste Disposal | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to empty pesticide containers is dangerous to human health. | Yes | 79 | 20.2 |

| No | 312 | 79.8 | |

| Triple-rinsing pesticide containers after emptying reduces the potential for environmental damage. | Yes | 336 | 85.9 |

| No | 55 | 14.1 | |

| Rinsed containers always contain pesticide residues. | Yes | 134 | 34.3 |

| No | 257 | 65.7 | |

| Disposing of leftover solutions in non-cropped areas may pose a threat to the environment. | Yes | 142 | 36.3 |

| No | 249 | 63.7 | |

| Using PPE during pesticide disposal (rinsing of used containers) is very important to avoid contamination. | Yes | 257 | 65.7 |

| No | 134 | 34.3 | |

| Discharging the rinsate into streams can contaminate drinking water sources. | Yes | 187 | 47.8 |

| No | 204 | 52.2 | |

| Throwing away empty pesticide containers in water streams or canals can contaminate the environment. | Yes | 148 | 37.9 |

| No | 243 | 62.1 | |

| Disposal of old stock pesticide solution with regular waste is harmful. | Yes | 258 | 66.0 |

| No | 133 | 34.0 | |

| Empty pesticide containers should not be reused as they still contain pesticide residues. | Yes | 132 | 33.8 |

| No | 259 | 66.2 | |

| Re-spraying the treated area with the leftover pesticide solution is a risky practice that can result in phytotoxicity or unacceptable residues in crops or soils. | Yes | 165 | 42.2 |

| No | 226 | 57.8 | |

Each disposal-practice item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Never, 5 = Always), with higher scores reflecting safer disposal practices. Items were summed to yield a composite Disposal Behaviour Score ranging from 10 to 50 (Cronbach’s α = 0.77). For analytical clarity and to guide purposive selection of participants for the qualitative phase, scores were grouped as follows:

- Safe: ≥41

- Intermediate: 26–40

- Unsafe: ≤25

These categories were used solely as analytical and sampling tools to ensure variation in disposal behaviour during the qualitative phase; they do not represent formal compliance thresholds or externally validated risk classifications.

Knowledge items were scored as binary responses (1 = correct, 0 = incorrect) to generate a total knowledge score ranging from 0 to 10. Content validity of the questionnaire was assessed by four experts in agricultural extension, environmental management and public health using the Item-Objective Congruence (IOC) method [28], and revisions were made prior to deployment.

A pilot study was conducted with 30 cocoa farmers (10 per region) to assess clarity, response time, and cultural appropriateness. Minor wording changes were made (e.g., simplifying “rinsate” to “leftover spray water”), and skip patterns were refined to improve flow. The pilot confirmed acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.77) and demonstrated that respondents understood all items, supporting the instrument’s suitability [28]. For the in-depth interview protocol, we used survey findings to inform its development for data collection. We developed the interview protocol to explore the factors affecting the farmers’ pesticide waste management. Four open-ended questions were asked about why these variables contributed to their pesticide waste disposal. The interview was semi-structured, allowing us to follow up with probing questions for clarification. The interview was audio-recorded in a local language. Before data collection began, we conducted a pilot study to assess the suitability of the questionnaires and the in-depth interview protocol. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.77) of the questionnaire was sufficient for data collection [28]. The in-depth interview protocol was modified based on the pilot study outcomes.

2.5. Data Analysis

Quantitative data were coded, entered, and analysed using SPSS software (version 23). Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistics were used to test for data normality (p > 0.05). We used the arithmetic mean and standard deviation to describe the continuous variables. Similarly, levels of disposal behaviour and knowledge of pesticide wastes were analysed using frequencies and percentages. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to assess the relationship between the determinants and disposal practices among the farmers.

The “disposal behaviour score” (10–50) was treated as a continuous dependent variable. Predictor variables included knowledge score, age, farm size, education, experience, training exposure, and presence of collection facilities. Multicollinearity diagnostics (Tolerance > 0.2; VIF < 5) confirmed model validity [29]. In the qualitative data analysis, audio recordings were manually transcribed for all respondents using a content analysis approach. This involved sorting the transcripts into “meaning units” (answers aligned with the study’s objectives) and coding them into themes. We identified all aspects of the transcripts to determine whether they were included in the list of meaning units by re-reading the original transcripts and comparing them with the final list. Therefore, homogeneous groups of meaning units were identified based on the interview questions, and manifest analysis was conducted using the respondents’ exact words.

Interview data were analysed following a conventional content analysis approach. Initial codes were inductively generated by two independent coders trained in qualitative analysis. Coding differences were discussed until consensus was reached, and inter-coder reliability achieved a Cohen’s κ = 0.82, indicating strong agreement. An audit trail of coding decisions and reflexive memos was maintained to enhance transparency. Data saturation was reached when no new codes emerged after three consecutive interviews. NVivo 12 software was used to support coding and theme organisation.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.1.1. Knowledge of Farmers Regarding Pesticide Wastes

Table 1 shows the participants’ knowledge regarding pesticide waste management. Generally, farmers’ knowledge of pesticide wastes was low. However, the majority acknowledged that triple-rinsing pesticide containers after emptying reduces the potential for environmental damage, “disposal of old stock pesticide solution with regular waste is harmful,” and “using PPE during pesticide disposal is very important to avoid contamination”. However, the farmers were unaware of the risks associated with the other items in the questionnaires. They believed empty pesticide containers were not harmful; rinsing them might remove pesticide residues, and discarding them would not contaminate canals or streams. The mean knowledge score (range = 0–10) was 5.2 ± 1.9, indicating moderate overall understanding, although awareness of container toxicity and water-body contamination remained low.

3.1.2. Farmers’ Practices When Disposing of Pesticide Wastes

Table 2 shows ten common pesticide disposal practices in the study area. Also, Figure 3 shows that the farmers’ disposal practices in the study location were improper and unsafe. For example, leaving pesticide containers in farmlands and throwing away the containers in water streams or canals were usually practised. Burning the empty pesticide containers, applying the rinsate over a non-cropped area, and re-applying the leftover on the same crop until it is empty were always practised by the majority of the farmers. Moreover, more than half of the farmers responded to the question (“keeping the containers for reuse for other domestic purposes”). However, most farmers never or rarely store (80.4%) leftover pesticide for another application. The composite “Disposal Behaviour Score” ranged from 12 to 48 (mean = 28.6 ± 7.9, Cronbach’s α = 0.77), showing that the majority of farmers fell within the “intermediate-to-unsafe” category.

Table 2.

Farmers’ disposal practices regarding pesticide wastes.

Figure 3.

Unsafe disposal of pesticide wastes (in this case, containers) in (i) a water stream close to a community and (ii) at one of the farms visited. Note: All photographs were taken by the research team during fieldwork with the landowner’s consent, and no identifiable personal information is shown.

3.1.3. Determinants of Pesticide Waste Disposal Practices Among the Farmers

Table 3 explains the multiple regression analysis used to assess the factors influencing the farmers’ disposal practices in Nigeria. Before regression, assumptions of linearity, normality, homoscedasticity, and independence of residuals were verified through visual inspection of P-P plots and residual scatterplots. Durbin–Watson = 1.93 indicated independence; Shapiro–Wilk test of residuals = 0.078 (p > 0.05) confirmed normality; and Cook’s D < 0.45 for all cases ruled out influential outliers. Multicollinearity diagnostics were acceptable (Tolerance > 0.2; VIF < 5) for all predictors [30]. The regression model incorporating age, knowledge, availability of collection facilities, education, experience, training, and farm size was significant (F(7, 383) = 48.62, p < 0.001) and explained 46.9% of the variance in safe disposal behaviour (R2 = 0.469). Knowledge of pesticide risks (β = 0.156, t = 3.849, p < 0.05) and the presence of collection facilities (β = 0.130, t = 3.441, p < 0.05) exerted a positive influence on farmers’ disposal behaviour, whereas age (β = −0.615, t = −10.169, p < 0.05) had a negative effect.

Table 3.

Multiple regression analysis.

Together, these findings confirm H1 and H2 (knowledge and facilities → safer disposal) and H3 (age → less safe disposal). The strong negative age effect suggests that younger farmers are more responsive to training and safer practices, while structural constraints, especially facility access, limit behaviour change across all groups.

3.2. Qualitative Findings

Data from qualitative analysis of 23 in-depth interview transcripts were used to explore determinants of disposal behaviour among cocoa farmers in Nigeria. Five sub-themes related to (1) attitudes to pesticide wastes after use; (2) disposal or collection facilities for pesticide wastes; (3) knowledge of risks associated with pesticide wastes; (4) social norms; and (5) membership of an association emerged from content analysis. Table 4 shows the resulting codes from content analysis.

Table 4.

Resulting codes generated from content analysis.

3.2.1. Sub-Theme 1: Negative Attitude Towards Pesticide Wastes After Use

Most farmers (n = 15) showed negative attitudes towards pesticide wastes, partly due to a lack of evidence caused by pesticide poisoning: “I normally wash pesticide containers close to a nearby stream. I think it is not bad practice as the water is not stagnant (flowing streams) and not seen anybody who fell sick after using from the water”. Some (n = 13) even believed that proper washing of container would remove pesticide residues: “I used them for food storage at home, and I think no residues left in the containers if washed properly with hot water and soap”.

3.2.2. Sub-Theme 2: Disposal or Collection Facilities

Most of the farmers (n = 21) interviewed reported a lack of collection facilities as a significant setback in their communities: “I do not have disposal materials to collect leftover solutions and expired pesticides, so I leave them on farms or bury them around the farm”. Despite the lack of these facilities, a few cocoa farmers (n = 7) still devise alternative strategies to avoid waste when using pesticides: “I make sure I prepare the pesticide solution required for the farm to avoid waste because there are no facilities to process them”. In addition, some farmers (n = 5) explained that an agricultural organisation donated a few collection facilities or cages as a pilot project for their communities. However, most facilities are currently non-functional because of poor awareness among the farmers and a lack of training on properly rinsing the containers before putting them in the collection cage. Eventually, most of these containers were rejected by the recyclers contracted for the projects: “There are some collection cages in the community donated by an agency for farmers, but they are no longer functioning. Many farmers were not adequately informed about this project and had no proper training on how to dispose of pesticide waste. The recycling people had to reject most containers because they said recycling would be difficult”.

3.2.3. Sub-Theme 3: Knowledge of Risks Associated with Pesticide Wastes

We observed that most farmers’ (n = 17) knowledge of pesticide wastes was low. They do not know that containers still harbour pesticide residues no matter the frequency of washing: “Once the chemical is drained, the container is safe to use. There can be no residues left behind, especially if properly washed with detergents and boiling water”. On the other hand, a few cocoa farmers (n = 3) were more informed about the danger of using empty pesticide containers: “Only farmers who do not know about the danger of pesticides could still reuse the containers as they still contain residues, no matter how hard one washes them”.

3.2.4. Sub-Theme 4: Social Norms

Some of the respondents (n = 9) used to follow other cocoa farmers’ behaviour in their communities when disposing of wastes due to social pressure: “I normally burn empty pesticide containers as that is what other farmers do in this community. There are no facilities to dispose of them after use”.

3.2.5. Sub-Theme 5: Membership in Farmers’ Association

Few cocoa farmers (n = 4) were aware of the danger posed by pesticide wastes to the environment at their local association meetings. They ensured that they disposed of the wastes safely: “I learned about the danger of these wastes through the farmers’ association in this community, which sensitised the members on handling some of the wastes to avoid poisoning”. For example, “I was advised to wash the empty pesticide containers three times and puncture them to avoid reuse for domestic activities”. One of them also learnt from the association that leftover solutions could be avoided if the right quantity of pesticides concerning the farm size were used: “I normally do not have excess pesticide solutions after spraying. This is what I learnt from the usual association meeting some time ago. Proper quantity of pesticides needs to be measured concerning the land area to be sprayed”. Also, the remaining two respondents claimed to always dispose of pesticide rinsates according to technical advice from their associations: “In the past, I do not care about these wastes, but now I do because of the risks associated with them as I was told from one the meetings I attended. It was suggested that pesticide wastes, especially rinsates, should be applied on non-cropped grassy land far away from any river to avoid contamination”.

3.3. Integrated Explanations for Mixed-Methods Convergence

The qualitative results provide explanatory depth to the quantitative findings and are summarised alongside them in Table 5 (Joint Display). Negative attitudes and social conformity (Sub-themes 1 and 4) help explain why many farmers continue unsafe practices despite awareness campaigns, corresponding to the moderate knowledge scores observed in Table 1. The lack of functional collection facilities (Sub-theme 2) is directly mirrored by quantitative evidence that access to collection systems significantly predicts safer behaviour (Table 3). Likewise, membership in farmers’ associations (Sub-theme 5) offers an informal mechanism for disseminating safety norms and practical advice, supporting the positive role of social learning highlighted in TPB-based behavioural theory. The joint display integrates these quantitative determinants (knowledge, facility access, and age) with their qualitative explanations of attitudes, social norms, and association learning. This side-by-side presentation illustrates how structural enablers (e.g., disposal cages, extension support) and behavioural drivers (knowledge, attitudes, norms) operate jointly rather than independently. The explanatory sequential design thus clarifies that the measured quantitative predictors are not stand-alone variables but empirical proxies for deeper qualitative mechanisms of belief formation, social influence, and institutional learning among cocoa farmers.

Table 5.

Joint display integrating quantitative and qualitative findings on pesticide waste disposal behaviour among Nigerian cocoa farmers.

4. Discussion

Disposal of pesticide wastes remains a persistent challenge for smallholder farmers in many low- and middle-income countries, where limited infrastructure and weak regulatory enforcement increase the risk of environmental contamination and human exposure. In cocoa-producing regions of Nigeria, these risks are compounded by rising pesticide use and the absence of clear guidance on safe post-use management. This study examined how cocoa farmers dispose of pesticide wastes and identified the behavioural and systemic factors shaping these practices using an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design. Quantitative findings showed that knowledge of pesticide risks, access to collection facilities, and farmers’ age together explained 46.9% of the variance in disposal behaviour. The qualitative phase further revealed that attitudes toward pesticide waste, social norms, and learning through farmer associations strongly influenced decision-making. Taken together, these results demonstrate that structural and behavioural drivers operate interdependently rather than independently. The mixed-methods approach enabled linking measurable determinants (knowledge, facility access, age) to the underlying mechanisms of belief formation, social influence, and practical constraints. In doing so, the study advances prior research—often limited to cross-sectional survey designs [13,23,31,32]—and further operationalises behavioural frameworks, such as the TPB, by showing that perceived norms and attitudes remain salient. In contrast, actual behavioural control is moderated by the availability of safe disposal infrastructure.

The present study found that unsafe disposal practices were widespread among cocoa farmers, including leaving empty containers on farms or in nearby streams, re-applying leftover spray mixtures, burning containers, and reusing them for domestic purposes. These behaviours are consistent with previous findings from Southwestern Nigeria [8] and other West African cocoa systems, where similar practices, such as selling or discarding containers containing household waste, have been reported [30,31]. Comparable patterns have also been documented beyond Africa. For example, the re-application of leftover pesticide solution on already treated crops was reported among 98.5% of Ghanaian farmers and 30% of farmers in Ardabil Province, Iran [13,32]. These practices reflect structural and behavioural challenges rather than simple negligence. Although knowledge of pesticide waste risks was generally low among our respondents (69.3% scoring below the midpoint), our findings suggest that unsafe disposal often persists because farmers perceive few viable alternatives and must prioritise crop protection, representing an expression of limited “perceived behavioural control.” The strong negative association between age and safe disposal behaviour further indicates generational differences in openness to new practices. At the same time, farmer associations also provided informal learning spaces that influenced everyday practices.

This study also identified key determinants of pesticide-waste disposal behaviour. Age was strongly associated with safe disposal practices, indicating that older farmers were less likely to adopt appropriate waste-handling behaviours. This pattern is consistent with earlier behavioural research linking age to resistance to practice change and lower perceived control over new technologies [23]. However, the relatively large effect size (β = −0.615) observed in this study suggests that age may also be acting as a proxy for other social or informational differences, such as variations in formal education, openness to innovation, or frequency of contact with extension services. Age should therefore be interpreted not only as a biological variable but as a composite indicator of accumulated experience, risk perception and access to learning opportunities. Future studies incorporating a broader range of psychosocial and institutional variables may help disentangle these pathways. Still, this finding highlights the need for generationally tailored training and communication strategies. In contrast, the availability of dedicated pesticide-container collection facilities was positively associated with safe disposal, reinforcing evidence from other regions that access to infrastructure is a critical enabling condition for compliance [33,34,35]. Notably, most study communities lacked functional collection points, leading well-informed farmers to resort to unsafe practices out of necessity. This underscores that education alone is unlikely to be effective where structural barriers persist. Sustainable improvement will therefore require both farmer-focused interventions and systemic reform, particularly the introduction of coordinated container-recovery or take-back schemes. EPR models implemented in countries such as South Africa and Brazil offer a relevant blueprint by distributing responsibility among importers, agro-dealers, and regulatory agencies, thereby institutionalising safe disposal pathways alongside behavioural change.

Knowledge of pesticide risks is a well-established determinant of pro-environmental behaviour among farmers [33], and our results are consistent with this evidence. Farmers with higher awareness of the persistence and toxicity of pesticide residues were significantly more likely to adopt safer disposal practices, including avoiding leftover spray solution and correctly rinsing and discarding containers. This aligns with studies showing that informed farmers better recognise the human health and environmental implications of poor disposal and are therefore more motivated to adopt protective behaviours [32,36]. However, knowledge rarely develops spontaneously. Training programmes and regular extension contact have been shown to strengthen risk understanding and reshape attitudes toward waste handling [34], underscoring the importance of embedding pesticide-waste education within existing advisory systems. These findings contribute to the wider literature by demonstrating that knowledge not only predicts safer behaviour in Nigeria but does so in a manner consistent with global patterns observed across different crops and regions. Strengthening farmer knowledge through targeted, context-appropriate training, therefore, remains an essential—though not sufficient—pillar of pesticide-waste governance.

Beyond knowledge and infrastructure, the qualitative phase demonstrated that attitudes, social norms and participation in farmer associations also shape disposal behaviour. Attitudes are central to behavioural adoption processes [33], and our interviews showed that where farmers perceived pesticide wastes as harmless or low-risk, unsafe practices were more likely to persist. Conversely, those exposed to peer discussion and collective learning—particularly through farmer associations—were more inclined to view safe disposal as both necessary and socially expected. These findings reinforce earlier work showing that attitudes influence safe handling practices [23] and that negative risk perceptions can translate into accidents and environmental harm [13]. Importantly, they also highlight that attitudinal change is rarely individual: it is embedded in community norms and shared learning environments. Interventions that strengthen positive attitudes at the group level may therefore have greater and more sustained effects than information campaigns directed solely at individuals.

Social influence also emerged as a critical driver of pesticide-waste behaviour. Farmers rarely act in isolation; instead, they observe and model what is considered acceptable within their communities [37,38]. Influential figures—such as cooperative leaders, experienced farmers and family members—play an important role in legitimising particular practices, whether safe or unsafe. When environmentally responsible behaviour becomes visible and widely practised, it signals to others that such actions are both expected and beneficial. Conversely, where unsafe disposal is normalised, deviation from these practices is unlikely.

Membership in farmers’ associations was particularly important in shaping these norms. Several respondents reported first learning about the risks of rinsates and container reuse through association meetings, where guidance on triple-rinsing and puncturing containers was provided. Similar findings have been reported in Ghana, where association members were more likely to receive pesticide-safety training and demonstrate higher awareness of environmental and health risks [31]. These findings suggest that associations can function as informal extension systems, supporting peer-to-peer learning and reinforcing pro-environmental norms. Taken together, the results indicate that improving pesticide waste disposal will require attention to behavioural, institutional, and infrastructural dimensions simultaneously. The study, therefore, contributes to the broader literature by showing how TPB constructs, particularly subjective norms and perceived behavioural control, interact with institutional and infrastructural constraints to shape farmers’ disposal practices. By integrating behavioural insights with policy-oriented recommendations, the research advances both theoretical understanding and practical solutions to pesticide governance challenges in Nigeria and comparable agricultural settings.

Global Relevance and Wider Implications

Although grounded in Nigeria’s cocoa sector, the findings of this study speak to a much broader challenge facing smallholder agriculture worldwide: how to manage pesticide-related wastes where infrastructure, regulatory enforcement and advisory services are only partially developed. Recent research from Latin America, Asia, and the Middle East demonstrates that unsafe disposal of containers and rinsates persists even where awareness has improved, suggesting that behaviour change is constrained by the interaction among knowledge, perceived control, and system capacity rather than by information deficits alone [5,7,10,14,26,33]. Our results reinforce this pattern by showing that farmers’ waste-management practices reflect both social and institutional realities, including peer norms, association learning, and the availability of safe collection pathways.

This study, therefore, contributes to current international debates on sustainable agricultural transitions by empirically distinguishing between behavioural drivers and structural enablers of safer pesticide management. In doing so, it aligns with wider scholarship showing that the uptake of sustainable practices—whether IPM adoption, organic conversion or responsible chemical stewardship—depends not only on individual risk perception but also on trust, institutional support and the presence of workable alternatives. A further contribution lies in demonstrating that disposal-related risks documented here mirror those observed in other pesticide-intensive crops, indicating that container waste should be addressed as a cross-commodity governance issue rather than a cocoa-specific concern. The mixed-methods approach used in this study provides explanatory depth that may assist policymakers and development agencies beyond Nigeria. By linking measurable behavioural determinants to the contextual mechanisms shaping farmers’ decisions, the findings help explain why regulatory measures alone have struggled to eliminate unsafe disposal practices internationally, and why farmer engagement, social learning, and accessible recovery infrastructure must evolve together if pesticide governance is to support global sustainability goals.

5. Practical Implications and Policy Relevance

The findings of this study highlight the urgent need for integrated interventions that combine behavioural change strategies with structural improvements in pesticide waste management systems. Drawing on the identified determinants—knowledge, facility access, and social norms—several feasible actions are proposed for implementation at both the farm and system levels, and are consistent with emerging good practices in the pesticide-governance literature [39,40,41].

5.1. Farm-Level Interventions

- Farmers should be trained and encouraged to triple-rinse empty containers immediately after use, puncture them to prevent reuse, and place them in designated collection points. Demonstrations during extension visits or association meetings could normalise these practices, reducing unsafe reuse for domestic purposes.

- Extension officers should promote precise pesticide measurement relative to farm size to minimise leftover solutions. As shown by Ghana’s Cocoa Research Institute’s farmer-field demonstrations, calibration training can significantly reduce pesticide residues and spray wastage.

- Since social norms and peer influence strongly affect disposal practices, farmer cooperatives and cocoa associations can serve as change agents. Integrating short behavioural modules into their monthly meetings or using peer champions can create positive social pressure for safer disposal.

- Given that age negatively influences safe disposal behaviour, training materials should be simplified and translated into local languages, using audio-visual demonstrations tailored to low-literacy, older populations.

- Promoting IPM alongside disposal education reduces dependence on synthetic pesticides and overall waste generation. Successful pilots in Cross River and Osun States show that IPM-based cocoa training increases farmers’ risk awareness and decreases pesticide misuse.

5.2. System-Level Interventions

- State agricultural development programmes, in partnership with private pesticide importers, should install “pesticide cages” or return bins at central farm clusters or agro-dealer shops. Similar models in South Africa’s CropLife Container Management Scheme demonstrate the viability of shared collection logistics.

- Importers and agro-dealers should share post-consumer responsibility for pesticide packaging. Nigeria’s National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) and NAFDAC could operationalise this under an EPR framework, ensuring that manufacturers finance safe collection and recycling.

- Embedding pesticide-waste modules within ongoing agricultural extension curricula (e.g., Agricultural development projects and Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security programmes) would ensure regular reinforcement of safe disposal skills and monitoring of compliance.

- Non-functional collection cages identified in the study highlight the need for sustained recycling markets. Partnerships between local governments, recyclers, and cocoa cooperatives can ensure collected containers are cleaned and reprocessed under safe conditions, creating local employment and circular-economy benefits.

5.3. Addressing Barriers and Enabling Factors

Behavioural and systemic change will depend on addressing three interlinked barriers identified in this study:

- Facility absence (infrastructure): resolved through EPR-led collection and recycling logistics.

- Low knowledge and attitude gaps (behavioural): tackled through targeted, participatory training and peer-led diffusion.

- Age-related inertia (socio-cultural): mitigated through mentoring, inclusive extension strategies, and intergenerational learning between younger and older farmers.

If properly implemented, these measures could significantly reduce unsafe pesticide disposal in Nigeria’s cocoa sector, advance compliance with international sustainability standards, and contribute to the zero-pollution and circular-economy targets under the African Union’s Green Recovery Action Plan.

6. Conclusions

This study examined cocoa farmers’ pesticide waste disposal practices and their determinants across Nigeria’s major producing regions using an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design. By combining quantitative predictors with qualitative insights, the study provided a more holistic understanding of how knowledge, infrastructure, and social context jointly shape farmers’ behaviours. Consistent with the study’s hypotheses, knowledge of pesticide risks and the availability of collection facilities were positively associated with safer disposal practices (supporting H1 and H2), whereas age was negatively associated (supporting H3). These findings affirm that improving farmers’ understanding and ensuring access to safe disposal infrastructure are mutually reinforcing conditions for behavioural change. Qualitative analysis further revealed that attitudes, social norms, and association membership underpin these quantitative relationships, indicating that safe disposal behaviour is not merely a matter of awareness but also of collective learning and perceived social expectations. Rather than reiterating the well-known hazards of unsafe disposal, this research advances understanding by identifying where behavioural and systemic interventions intersect. The findings demonstrate that sustainable change will depend on both policy instruments—such as take-back schemes, recycling partnerships, and IPM support—and behavioural mechanisms that leverage peer influence and association-based training. In practical terms, extension services should integrate pesticide-waste management modules into existing farmer training curricula, target older farmers with context-appropriate materials, and mobilise associations as peer-education hubs. At the system level, establishing functional collection and recycling infrastructure, underpinned by EPR regulations, will institutionalise safer disposal pathways.

Overall, this study underscores that addressing pesticide waste in Nigeria’s cocoa sector requires a dual strategy that aligns behavioural change with institutional reform. By mapping these interdependencies, the research provides a scalable model for environmental health promotion and policy design in other low- and middle-income agricultural contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pollutants6010008/s1. Part I: Demographic Questions; Part II: Knowledge and practices when handling pesticide wastes after use; Revised Interview Guide; Qualitative Phase–In-Depth Interview Protocol; Semi-Structured Interview Questions for Cocoa Farmers; Section A—Disposal Practices; Section B—Attitudes Toward Pesticide Wastes; Section C—Knowledge of Risks; Section D—Social Norms & Influence; Section E—Membership in Associations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.O. methodology, O.O.; software, C.C.O.; validation, O.O., K.O. and L.O.; formal analysis, O.O.; investigation, O.O.; data curation, C.C.O.; writing—original draft preparation, O.O.; writing—review and editing, C.C.O. and O.A.-A.; visualization, L.O. and K.O.; supervision, O.O.; project administration, O.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adebanjo-Aina, O.; Oludoye, O. Impact of Nitrogen Fertiliser Usage in Agriculture on Water Quality. Pollutants 2025, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademola, S.M.; Esan, V.I.; Sangoyomi, T.E. Assessment of Pesticide Knowledge, Safety Practices and Postharvest Handling among Cocoa Farmers in South Western Nigeria. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, M.; Achal, V. A Comprehensive Review on Environmental and Human Health Impacts of Chemical Pesticide Usage. Emerg. Contam. 2024, 11, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaseer, S.S.; Jaspers, V.L.B.; Orsini, L.; Vlahos, P.; Al-Hazmi, H.E.; Hollert, H. Beyond the Field: How Pesticide Drift Endangers Biodiversity. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 366, 125526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Huang, J. How to Effectively Improve Pesticide Waste Governance: A Perspective of Reverse Logistics. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossa, A.; Mohafrash, S. Disposal of Expired Empty Containers and Waste from Pesticides. Egypt. J. Chem. 2023, 67, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Naqvi, S.A.A.; Mehdi, M.A.; Usman, M.; Ali, S.; Shah, A.A.; Hussain, B. An Analysis of the Circular Economy Practices of Pesticide Container Waste in Pakistan. Recycling 2022, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosan, M.; Oladepo, W.; Ajibade, T. Assessment of Pesticide Wastes Disposal Practices by Cocoa Farmers in Southwestern Nigeria. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 2020, 46, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshingbade, O.S.; Moda, H.M.; Akinsete, S.J.; Adejumo, M.; Hassan, N. Determinants of Safe Pesticide Handling and Application among Rural Farmers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Flores, E.; Sarrà, M.; Blánquez, P. A Review on the Management of Rinse Wastewater in the Agricultural Sector. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, Z. Global Mapping of Freshwater Contamination by Pesticides and Implications for Agriculture and Water Resource Protection. iScience 2025, 28, 112861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Pesticide Waste Management and Agricultural Environmental Protection. In 2021 6th International Conference on Social Sciences and Economic Development (ICSSED 2021); Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 900–903. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, A.; Emami, N.; Damalas, C.A. Farmers’ Behavior towards Safe Pesticide Handling: An Analysis with the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A.; Emami, N.; Damalas, C. Monitoring Point Source Pollution by Pesticide Use: An Analysis of Farmers’ Environmental Behavior in Waste Disposal. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 25, 6711–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehinde, A.; Ojo, T.; Ogunleye, A.; Ogundeji, A. Impact of access to cash remittances on cocoa yield in Southwestern Nigeria. Sustain. Futures 2024, 7, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adejori, A.A.; Akinnagbe, O.M. Assessment of Farmers′ Utilization of Approved Pesticides in Cocoa Farms in Ondo State, Nigeria. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminu, F.O. Pesticide use and health hazards among cocoa farmers: Evidence from Ondo and Kwara states of Nigeria. Niger. Agric. J. 2020, 51, 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- Yami, M.; Lenis, L.-T.; Maiwad, R.; Wossen, T.; Falade Titilayo, D.O.; Oyinbo, O.; Yamauchi, F.; Chamberlin, J.; Feleke, S.; Abdoulaye, T. Farmers’ Pesticide Use, Disposal Behavior, and Pre-Harvest Interval: A Case Study from Nigeria. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1520943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Pereira, L.; Jane, K. Mixed Methods Research: Combining Both Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384402328_Mixed_Methods_Research_Combining_both_qualitative_and_quantitative_approaches (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Oludoye, O.O.; Robson, M.G.; Siriwong, W. Using the Socio-Ecological Model to Frame the Influence of Stakeholders on Cocoa Farmers’ Pesticide Safety in Nigeria: Findings from a Qualitative Study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 2357–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oludoye, O.O.; Siriwong, W.; Robson, M.G. Pesticide safety behavior among cocoa farmers in Nigeria: Current trends and determinants. J. Agromed. 2023, 28, 470–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes-Brown, T.K. The Role of Sampling in an Explanatory Sequential Mixed Methods Study: General Applications of the Transformative Paradigm. Methods Psychol. 2025, 12, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A.; Bondori, A.; Allahyari, M.S.; Damalas, C.A. Modeling farmers’ intention to use pesticides: An expanded version of the theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 248, 109291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damalas, C.A.; Telidis, G.K.; Thanos, S.D. Assessing farmers’ practices on disposal of pesticide waste after use. Sci. Total. Environ. 2008, 390, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huici, O.; Skovgaard, M.; Condarco, G.; Jørs, E.; Jensen, O.C. Management of Empty Pesticide Containers—A Study of Practices in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Environ. Health Insights 2017, 11, 1178630217716917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharafi, K.; Pirsaheb, M.; Maleki, S.; Arfaeinia, H.; Karimyan, K.; Moradi, M.; Safari, Y. Knowledge, attitude and practices of farmers about pesticide use, risks, and wastes; a cross-sectional study (Kermanshah, Iran). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arowolo, A.; Shuaibu, S.; Sanusi, M.; Fanimo, D.O. Analysis of the determinants of profit from cocoa beans marketing in Ogun State, Nigeria. J. Agr. Sci. Environ. 2016, 16, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.C.; Carlson, L. Indexes of item-objective congruence for multidimensional items. Int. J. Test. 2003, 3, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.; Poga, M. Dealing with Multicollinearity in Factor Analysis: The Problem, Detections, and Solutions. Open J. Stat. 2023, 13, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujang, M.A.; Omar, E.D.; Foo, D.H.P.; Hon, Y.K. Sample Size Determination for Conducting a Pilot Study to Assess Reliability of a Questionnaire. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2024, 49, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimi, M.O.; Muhammad, I.H.; Udensi, L.O.; Akpojubaro, E.H. Assessment of Safety Practices and Farmers Behaviors Adopted When Handling Pesticides in Rural Kano State, Nigeria. Arts Humanit. Open Access J. 2020, 4, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, K.O.; Dankyi, E.; Amponsah, I.K.; Awudzi, G.K.; Amponsah, E.; Darko, G. Knowledge, Perception, and Pesticide Application Practices among Smallholder Cocoa Farmers in Four Ghanaian Cocoa-Growing Regions. Toxicol. Rep. 2023, 10, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaki, M.Y.; Lehberger, M.; Bavorova, M.; Igbasan, B.T.; Kächele, H. Effectiveness of Pesticide Stakeholders’ Information on Pesticide Handling Knowledge and Behaviour of Smallholder Farmers in Ogun State, Nigeria. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 17185–17204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondori, A.; Bagheri, A.; Allahyari, M.S.; Damalas, C.A. Pesticide waste disposal among farmers of Moghan region of Iran: Current trends and determinants of behavior. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agmas, B.; Adugna, M. Attitudes and Practices of Farmers with Regard to Pesticide Use in NorthWest Ethiopia. Cogent Environ. Sci. 2020, 6, 1791462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshalati, L.M.J. Limited Knowledge and Unsafe Practices in Usage of Pesticides and the Associated Toxicity Symptoms among Farmers in Tullo and Finchawa Rural Kebeles, Hawassa City, Sidama Regional State, Southern Ethiopia. In Emerging Contaminants; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleb, A.; Ademas, A.; Abebe, M.; Berihun, G.; Desye, B.; Bezie, A.E. Knowledge of Health Risks, Safety Practices, Acute Pesticide Poisoning, and Associated Factors among Farmers in Rural Irrigation Areas of Northeastern Ethiopia. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1474487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessart, F.J.; Barreiro-Hurlé, J.; van Bavel, R. Behavioural factors affecting the adoption of sustainable farming practices: A policy-oriented review. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2019, 46, 417–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugeta, T.; Teklemariam, H.; Desta, T.T. Drivers of the unintended use of emptied chemical containers by smallholder farmers. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, L.; Yudoko, G.; Okdinawati, L. Towards a Closed-Loop Supply Chain: Assessing Current Practices in Empty Pesticide Container Management in Indonesia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga Marsola, K.; Leda Ramos de Oliveira, A.; Filassi, M.; Elias, A.A.; Andrade Rodrigues, F. Reverse logistics of empty pesticide containers: Solution or a problem? Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2021, 14, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.