Abstract

Eutrophication is a major threat to freshwater ecosystems, leading to harmful algal blooms, biodiversity loss, and hypoxia. Excessive nutrient loading, primarily from nitrates and phosphates, is driven by fertilizer runoff, sewage discharge, and agricultural practices. Sediment microbial fuel cells (sMFCs) have emerged as a potential bioremediation strategy for nutrient removal while generating electricity. Although various studies have explored ways to enhance sMFC performance, limited research has examined the relationship between external resistance, electricity generation, and nutrient removal efficiency. This study demonstrated effective nutrient removal from overlying water, with 1200 Ω achieving the highest nitrate and phosphate removal efficiency at 59.0% and 32.2%, respectively. The impact of external resistances (510 Ω and 1200 Ω) on sMFC performance was evaluated, with the 1200 Ω configuration generating a maximum voltage of 466.7 mV and the 510 Ω configuration generating a maximum current of 0.56 mA. These findings show that external resistance plays a major role in both electrochemical performance and nutrient-removal efficiency. Higher external resistance consistently resulted in greater voltage output and improved removal of nitrate and phosphate. The findings also indicate that sMFCs can serve as a dual-purpose technology for nutrient removal and electricity generation. The power output may be sufficient to support small, eco-friendly biosensing devices in remote aquatic environments while mitigating eutrophication.

1. Introduction

Excessive fertilizer use, improper sewage disposal, and natural runoff contribute to elevated nitrate and phosphate concentrations in lentic water bodies [1,2]. These nutrients drive eutrophication, which can trigger algal blooms and subsequent oxygen depletion that severely disrupt aquatic life. During bloom events, algae block sunlight from reaching submerged vegetation and consume dissolved oxygen; after the bloom collapses, microbial decomposition further lowers oxygen levels, potentially creating hypoxic or anoxic “dead zones” incapable of supporting most organisms [3]. In addition to water-column effects, sediments serve as long-term sinks for contaminants. For instance, work in Boka Kotorska Bay showed that surface sediments contained high levels of arsenic and chromium, demonstrating the persistence of anthropogenic pollution in vulnerable aquatic systems [4]. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) further contribute to sediment contamination, posing carcinogenic and mutagenic risks to benthic organisms and often remaining undetected in routine surface-water monitoring [5]. Collectively, these conditions drive biodiversity loss, degrade water quality, and disturb ecological balance in freshwater environments, underscoring the need for practical, environmentally friendly remediation tools. In response, several mitigation strategies have been investigated [6], including the development of specialized microbial fuel cells (MFCs) capable of removing excess nutrients and limiting the buildup of organic matter and its associated environmental impacts.

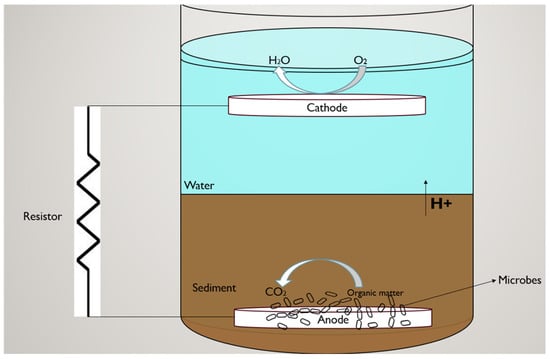

Microbial fuel cells generate electricity through the microbial oxidation of organic matter in wastewater, converting chemical energy directly into electrical energy [7]. A typical MFC consists of three key components: an anode, a cathode, and a membrane. At the anode, microorganisms break down organic substrates and release electrons, which flow through an external resistor to the cathode, where they complete the circuit [8]. These fuel cells are considered environmentally friendly and cost-effective, offering both ecological and economic benefits by reducing water pollution and promoting biodiversity in aquatic ecosystems.

Building on these principles, a specific type of MFC known as the sediment microbial fuel cell (sMFC) has proven particularly effective for in situ bioremediation in freshwater environments. These systems utilize organic-rich sediment as the substrate, with the anode embedded in anaerobic sediment layers and the cathode placed in the overlying aerobic water column [9,10,11,12]. Microbes oxidize organic material at the anode, releasing electrons that travel through a connecting wire to the cathode, where they reduce oxygen to form water. The performance of sMFC is strongly influenced by sediment characteristics, particularly the presence of exoelectrogenic bacteria and organic carbon content, as well as environmental factors such as pH, moisture content, and hydrological variations, all of which affect electrical current generation and overall power output [13]. In these systems, sediment also functions as a natural membrane between electrodes, while the use of highly conductive, permeable, and cost-effective materials, typically carbon- or metal-based, enhances both electricity generation and pollutant removal [14].

An important operational factor in optimizing sMFC performance is the external resistor, which regulates electron flow between the anode and cathode and can influence microbial activity at the anode [15]. Optimizing external resistance is essential for maintaining efficient electron transfer and maximizing both power output and pollutant removal efficiency. Studies have shown that increasing external resistance can improve electricity generation and enhance the removal of nutrients such as nitrate and phosphate; however, these benefits depend on maintaining a balance with internal system resistance [16]. Previous works have tested external resistances ranging from 2 to 33 kΩ [17,18,19], with power densities reported between 3.15 mW/m2 and 1410 mW/m2 for resistance values between 100 and 1000 Ω [13,18].

The parameters affecting electricity generation in sMFCs also affect their ability to remove pollutants like nitrate and phosphate from aquatic environments. These nutrients, commonly associated with eutrophication, are of particular concern in wastewater and freshwater ecosystems. Studies have demonstrated the capacity of sMFCs to degrade organic waste and facilitate phosphate removal through microbial processes [20]. Jin et al. [21] found that single-chamber MFCs operating in sediment-rich conditions effectively reduced nitrate concentrations, with enhanced microbial performance contributing to greater efficiency. Moreover, denitrification may occur at the cathode, where nitrate acts as the terminal electron acceptor. Advanced configurations, such as dual cathodes or aerated cathode chambers, have achieved nitrate removal efficiencies exceeding 90% [22], further highlighting the potential of sMFCs as multifunctional systems for both energy generation and bioremediation.

Although sMFCs have been studied for electricity generation, wastewater treatment, and biosensing applications, there remains a limited understanding of how electrical performance relates directly to nutrient removal efficiency in freshwater systems. Existing studies often examine power output or nutrient reduction independently, without explicitly linking the two processes or evaluating how operational parameters, particularly external resistance, simultaneously shape electron transfer and bioremediation effectiveness. As a result, the conditions that optimize both energy production and the removal of eutrophication-driving nutrients such as nitrate and phosphate remain poorly defined. This study addresses this gap by systematically testing how different external resistances influence power generation and nutrient removal, thereby clarifying the functional relationship between electrical output and remediation performance in sMFCs.

Building on prior findings, this study further investigates how key operational factors influence sMFC performance, particularly in the context of bioremediation. While previous research has highlighted the potential of sMFCs for wastewater treatment and biosensing, few studies have directly examined the relationship between electrical output and nutrient removal efficiency. To address this gap, the present study assesses the effects of varying external resistances on the removal of nitrate and phosphate in freshwater systems. Specifically, it aims to determine whether a measurable correlation exists between power generation and nutrient removal efficiency, thereby advancing our understanding of the dual functionality of sMFCs as both energy producers and environmental remediation tools.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sediment Collection

Sediment samples were collected from a pond at the University of The Bahamas during the wet season. The sediment was obtained from a depth of 5–30 cm below the sediment-water interface using a shovel, immediately transported to the laboratory, and stored until use. The sediment was enclosed in a container that was placed away from air conditioning vents and direct sunlight, with a constant room temperature of 23–26 °C in order to preserve its moisture and natural microbial community. Prior to assembly, the sediment was sieved to remove unwanted materials such as rocks, shells, and plant roots to ensure uniformity for use in the sMFC.

2.2. sMFC Assembly

Fifteen sMFCs were constructed using 1.5 L bottles in a single chamber, sediment overlying water design with carbon felt electrodes (AvCarb® Material Solutions, Lowell, MA, USA, 25 cm2; purchased from the Fuel Cell Store, https://www.fuelcellstore.com) (accessed on 15 July 2023) serving as both the anode and the cathode. Each electrode was entwined with titanium wire, and carbon felt was chosen for its high electrical conductivity, increased surface area, and porosity, which enhance oxidation and reduction reaction sites for microbial activity [23]. The electrodes were rinsed thoroughly with deionized water and allowed to air-dry before use. The sMFC design was adapted from Wang et al. [24] with minor modifications. Each unit consisted of a 1-inch sediment layer placed at the bottom of the bottle, followed by the anode, which was then covered with an additional 2-inch layer of sediment to maintain anaerobic conditions necessary for microbial respiration, as illustrated in Scheme 1. The cathode was suspended in 400 mL of overlying water, simulating aerobic conditions. No physical membrane was used, as sediment acted as a natural barrier. Representative images of the fully assembled sMFCs are provided in Figure S1.

Scheme 1.

Representation of the sediment microbial fuel cell (sMFC) system. The diagram illustrates the anode embedded within the sediment, the cathode positioned in the overlying water, and the external resistor connecting the electrodes. Microbial oxidation of organic matter at the anode generates electrons and protons, supporting electricity production and biogeochemical processes.

Twelve of the fifteen sMFCs were connected to external resistors and operated at either 510 Ω or 1200 Ω to regulate electron flow between the electrodes. These external resistances were selected based on previous sMFC studies to represent low and moderate resistance levels within an optimal operational range [25]. The sMFCs were divided into three groups (A–C), with Groups A and B consisting of six replicates each, and Group C containing three replicates. Each replicate was analyzed separately in all groups. Group A was operated with 510 Ω resistors, while Group B was connected to 1200 Ω resistors. Group C served as the control and was left as an open circuit with no external resistance. All fifteen sMFCs were kept under open-air laboratory conditions, protected from direct sunlight and air-conditioning vents, with room temperature maintained between 23 °C and 26 °C. Minor evaporation was replaced to maintain the 400 mL overlying water volume.

2.3. Voltage & Chemical Analysis

The voltage generated by each sMFC was measured using a BTMETER BT-90EPC Digital Multimeter. Voltage readings were taken daily between 12:00 p.m. and 2:00 p.m. to maintain a consistent measurement timeframe. The current (I) and power density were calculated using Ohm’s law (I = V/R), where I represents the current (A), V is the voltage (mV) measured between the anode and cathode, and R is the resistance (Ω). The current density (A/m2) and power density (W/m2) were determined by dividing the measured current and power by the total effective anode area (m2) [26]. The pH of the sMFCs was measured on Day 27 and then daily from Day 30 to Day 50 using a Hanna Instruments probe (Model HI9811-51, Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA). All instruments were calibrated prior to use according to the manufacturer’s instructions to ensure measurement accuracy.

Following nutrient dosing on Day 28, the initial concentrations in the overlying water were measured for each treatment. Nitrate concentrations were 269.8 mg/L in the 510 Ω cells, 275.2 mg/L in the 1200 Ω cells, and 254 mg/L in the control. Initial phosphate concentrations were 278.7 mg/L (510 Ω), 242.3 mg/L (1200 Ω), and 384 mg/L in the control. Removal efficiency was calculated using the initial concentration measured for each individual sMFC. Following nutrient addition, the cathodes were manually repositioned to maintain their original submersion depth and distance from the sediment water interface, ensuring consistent aerobic conditions for oxygen reduction. Beginning on Day 30, nitrate and phosphate concentrations in the overlying water were monitored for a 20-day period using the SEM2260 Soil Sensor Analyzer (Sentec, Shanghai, China). Nutrient measurements were collected daily during this period. Although this sensor is primarily designed for soil applications, a preliminary comparison was conducted using the LaMotte Nitrate-Nitrogen Test Kit (Code 3519-01, LaMotte Company, Chestertown, MD, USA) and the LaMotte Orthophosphate Test Kit (Code 4408-01, LaMotte Company, Chestertown, MD, USA) to assess the suitability of the sensor for aqueous measurements. The results from both methods showed general agreement in the magnitude and trend of nutrient changes across treatment groups. However, due to the soil-specific calibration of the SEM2260, the nutrient data presented should be interpreted as semi-quantitative estimates, used to assess relative changes in concentration rather than precise absolute values. The removal efficiency (%) of nitrate and phosphate was calculated using Equation (1):

where C0 represents the initial concentration, and Cₜ represents the final concentration after the experimental period.

Removal Efficiency (%) = (C initial − C final/C initial) × 100

One-way ANOVA tests were done to contrast nutrient removal efficiencies (nitrogen, phosphorus) in the experimental groups (A-510, B-1200) against the control group (no resistance). With there being statistically significant results by p < 0.05.

All experiments were done in triplicate, with the nutrient concentrations and removal efficiencies being represented by mean ± standard error.

3. Results

3.1. Electricity Production by sMFCs

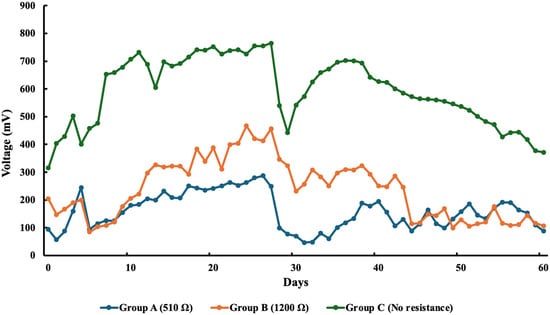

Figure 1 illustrates the average voltage from each group over the 61-day experimental period. The average initial voltages across all groups on Day 1 were 94 mV (Group A), 204 mV (Group B), and 220 mV (Group C).

Figure 1.

The average voltage from each group over the course of 61 days in the experiment.

Once the circuits were closed for the experimental groups (excluding Group C, which remained as the open-circuit control), a decrease in voltage was observed during the initial days. However, over time, the voltages stabilized. The control group (Group C) generated the highest average voltage (765 mV), while among the experimental groups, Group B exhibited the highest voltage output, reaching 467 mV on Day 25.

Following the addition of nutrients to all sMFCs, a notable drop in voltage was observed across all groups. In the control group (Group C), the voltage declined from 765 mV to 539 mV. Similar reductions were observed in the experimental groups, with Group A (510 Ω) dropping from 249 mV to 99 mV and Group B (1200 Ω) from 456 mV to 346 mV. Despite this initial decline, voltage levels gradually increased following nutrient enrichment but declined again toward the end of the experiment. The final average voltages recorded were 89 mV for Group A, 107 mV for Group B, and 372 mV for Group C.

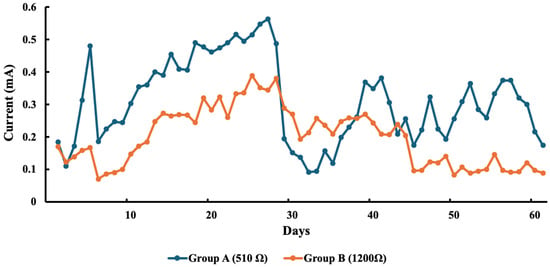

In terms of current production, the initial average readings for Groups A and B were 0.19 mA and 0.17 mA, respectively. Although these values increased over time, they experienced an initial decline following nutrient addition. By the end of the experiment, the final current readings were 0.17 mA for Group A and 0.10 mA for Group B (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Average current generated by each sMFC of each group.

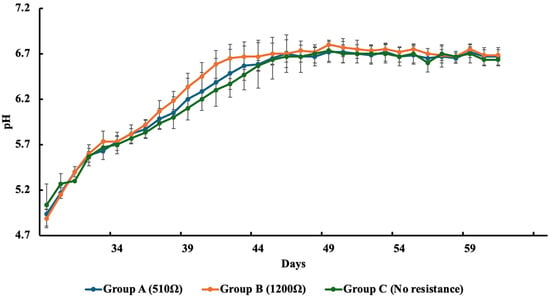

3.2. pH Dynamic

Figure 3 illustrates the average pH levels recorded in each group following the addition of nutrients. On the first day after nutrient enrichment, pH values across all cells ranged from 4.9 to 5.3, with the highest value (5.3) observed in Group C and the lowest (4.9) in Groups A and B. As the experiment progressed, pH levels in the overlying water gradually increased in all groups. By the end of the incubation, final pH values stabilized at 6.7 for Group A, 6.7 for Group B, and 6.3 for Group C, indicating a consistent upward trend across both the experimental and control groups.

Figure 3.

Average pH of each group after nutrients were added. Values represent the mean ± standard error (SE).

3.3. Nitrate and Phosphate Removal

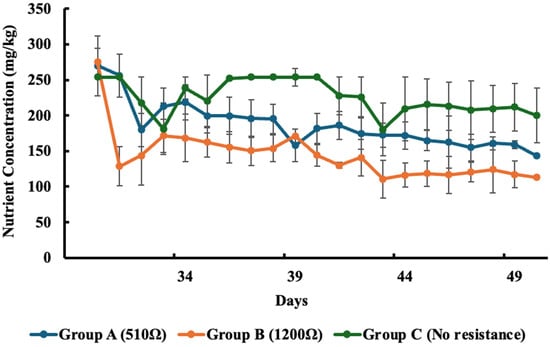

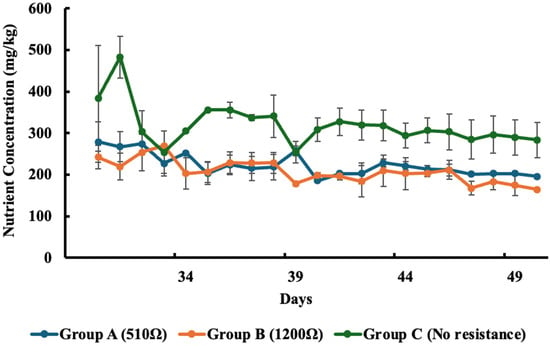

Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the changes in nitrate and phosphate concentrations in the overlying water throughout the experiment. A consistent decline in nutrient levels was observed across both control and experimental groups, indicating active nutrient removal over the 21-day monitoring period.

Figure 4.

Concentration of nitrate removed in each group over time. Values represent the mean ± standard error (SE).

Figure 5.

Concentration of phosphate in each group over time. Values represent the mean ± standard error (SE).

For nitrate removal, all groups showed a reduction in concentration over time. From Day 30 to Day 50, nitrate levels (mg/kg) decreased from 269.8 to 143.3 in Group A (510 Ω), 275.1 to 112.8 in Group B (1200 Ω), and 254.0 to 200.0 in Group C (Control). These changes correspond to nitrate removal efficiencies of 46.9% for Group A, 59.0% for Group B, and 21.3% for Group C. Among the experimental setups, Group B achieved the highest removal efficiency, indicating a strong influence of the 1200 Ω external resistance on nitrate removal performance.

Similarly, phosphate concentrations declined across all groups over the course of the experiment. Measured from Day 30 to Day 50, phosphate levels (mg/kg) dropped from 278.8 to 195.5 in Group A, 242.0 to 164.2 in Group B, and 384.0 to 283.3 in Group C. These correspond to phosphate removal efficiencies of 29.8% in Group A, 32.2% in Group B, and 26.2% in the control (Group C). Group B exhibited the most effective phosphate removal.

4. Discussion

The voltage output of all sMFCs prior to nutrient addition ranged from 249 to 765 mV, consistent with previously reported values, such as those by Feregrino-Rivas et al. [13], where voltages ranged between 400 and 700 mV. The control group exhibited the highest voltage (765 mV), likely due to the absence of an external resistor. Without an external load, current flow is minimal, resulting in a higher measured voltage across the cell. In contrast, experimental groups with external resistors displayed lower voltages, as the resistors controlled both current and voltage output. According to Jacobi’s Law, the maximum power output from an MFC is achieved when the external resistance matches the internal resistance of the system [27,28]. High external resistance tends to produce higher voltage but lower current, while low external resistance results in higher current but reduced voltage. Similar trends were observed in this study, as illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2. After the addition of nutrients, voltage levels in most cells declined initially, with some recovering over time. This pattern aligns with previous findings suggesting that nitrate addition can temporarily disrupt microbial communities in sediments, inhibiting electron transfer and reducing power output [29]. Similarly, phosphate inputs may alter redox conditions and shift microbial community structures in ways that further limit electron flow, thereby decreasing voltage production [30]. This effect was evident in the present study, where the control group (Group C), which lacked an external resistor, maintained a relatively high average voltage of 372 mV, while Group B, which operated under a 1200 Ω external resistance, declined to an average of 107 mV post-treatment.

Furthermore, introducing nutrients at the cathode can affect the electrochemical environment by increasing internal resistance or promoting the formation of secondary compounds, both of which may hinder voltage production [31]. The oxygen reduction reaction at the cathode, where electrons and protons combine to form water, is inherently slow due to its high activation energy. The addition of nutrients may worsen this issue, especially when other microorganisms utilize those nutrients, thereby reducing the availability of reactants and lowering the overall efficiency of the cathodic process [31,32]. These results support the conclusion that both nutrient enrichment and external circuit configuration significantly influence electrochemical performance in sMFCs. While increased ionic concentration typically improves ionic conductivity and thereby reduces internal resistance, leading to increased voltage output [33], the sudden shift following nutrient replacement in our experiment may have disrupted ion transport or placed stress on microbial communities, resulting in the observed transient decline in voltage. Additionally, evaporation of the overlying water also contributed to the decrease in voltage as the experiment went on. This caused an increase in internal resistance and disrupted microbial activity, thus leading to a lower voltage [34].

Although this study aimed to investigate whether a measurable correlation exists between power generation and nutrient removal efficiency in sMFCs, the relationship observed was not strictly proportional. Nonetheless, a general alignment between electrochemical performance and remediation efficiency emerged, particularly in the 1200 Ω treatment. Group B, which demonstrated the highest average voltage among the experimental groups and a stable post-enrichment recovery, also exhibited the most effective nitrate (59.0%) and phosphate (32.2%) removal. These findings suggest that elevated voltage may reflect enhanced microbial respiratory activity and more favorable redox conditions, which are conducive to denitrification and phosphate assimilation. However, sMFC with higher current output, such as Group A (510 Ω), did not consistently exhibit greater nutrient reduction, indicating that current generation alone may not serve as a reliable proxy for bioremediation performance. This outcome aligns with previous studies suggesting that nutrient removal in sMFCs is governed by complex interactions among microbial community structure, electron acceptor availability, and redox gradients rather than electrical output alone [16,21]. Therefore, while electrical performance provides useful insight into microbial activity, nutrient removal appears more directly influenced by localized biogeochemical processes occurring at the electrode-sediment interface.

There were also notable changes in pH values. The day before nutrient addition, the initial pH values in Groups A-C were 8.3, 8.0, and 7.7, respectively. Following the addition of nitrate and phosphate compounds, pH values in the overlying water decreased sharply, with Group A dropping from 8.3 to 4.9, Group B from 8.0 to 4.9, and Group C from 7.7 to 5.0. In sMFCs, pH typically decreases due to oxidation reactions at the anode, where electrogenic bacteria release H+ ions, which migrate to the cathode, leading to acidification. Additionally, nitrification may have occurred at the cathode under aerobic conditions, as nitrifying bacteria may have oxidized pre-existing ammonium in the system to nitrate, contributing to acidification through proton release during the nitrification process [35]. However, in this experiment, pH levels in all groups gradually increased over time, eventually stabilizing between 6.6 and 6.7. This increase in pH may be linked to the consumption of protons (H+) during the oxygen reduction reaction in the cathode and the limited movement of H+ from the anode to the cathode. This reaction consumes protons from the surrounding environment. In conventional MFCs with proton exchange membranes, H+ ions produced at the anode can move more freely to the cathode to balance this consumption. However, proton transfer is much slower and less efficient in sMFCs, where the sediment acts as a natural separator. As a result, the continual uptake of H+ at the cathode is not matched by sufficient proton replenishment from the anode side. This imbalance leads to a local depletion of H+ ions at the cathode, which causes the overlaying water to become more alkaline, resulting in a gradual increase in pH [36,37]. Another reason for the increase in pH can be attributed to oxygen reduction at the cathode, leading to a rise in pH in the cells. Additionally, ammonification of organic nitrogen in sediments may also contribute to pH elevation, particularly under reducing conditions [38].

In this study, KNO3 and KH2PO4 were added to each sMFC to simulate eutrophic conditions typically found in nutrient-rich aquatic environments. Over time, nitrate and phosphate concentrations declined, with the 1200 Ω treatment exhibiting the highest removal efficiencies, 59.0% for nitrate and 37% for phosphate. Comparable phosphate removal efficiencies have been reported in benthic sMFC systems, with values ranging between 38 and 79% depending on sediment characteristics and operating conditions [39]. Nitrate removal efficiencies can vary widely among MFC configurations, with some systems achieving reductions of up to 90% under optimized conditions [40]. These published ranges help contextualize the phosphate removal rates (32–37%) and nitrate removal efficiency (59%) observed in the present study. The observed nitrate reduction is primarily attributed to microbial metabolic processes, where nitrate serves as an alternative electron acceptor in the absence of oxygen, particularly at the cathode [21]. Total nitrogen loss likely resulted from a combination of denitrification and ammonia volatilization, though nitrate itself was primarily removed via denitrification. Denitrification involves the microbial conversion of nitrate to nitrogen gas under anaerobic conditions, a process facilitated by denitrifying bacteria in the sediment near the anode [41]. Denitrifying bacteria such as Pseudomonas spp. have been identified in recent studies as major contributors to nitrate removal in microbial fuel cells, particularly at the cathode, where nitrate can serve as an alternative electron acceptor [42]. Exoelectrogenic bacteria such as Geobacter spp. also play an important role, as they facilitate electron transfer from organic matter oxidation and have been associated with enhanced nitrate reduction in MFC systems [43]. The presence and activity of these microbial communities may therefore have contributed to the nitrate removal patterns observed in this study. The addition of nitrate may have influenced the redox potential at both electrodes, favoring the activity of these bacteria. Moreover, the system pH, maintained around 6, may have supported these processes, as denitrification operates efficiently in mildly acidic to neutral conditions [44]. Concurrently, elevated pH in the cathode chamber may have promoted ammonia volatilization, further contributing to nitrogen loss, a trend consistent with previous findings linking pH increases to enhanced nitrogen removal [34].

Phosphate concentrations declined in both the control and experimental groups, indicating active removal processes within the sMFCs. Phosphate removal in these systems occurs through several mechanisms, including adsorption to iron compounds in the sediment, chemical precipitation that renders phosphate insoluble, and microbial uptake. Previous studies have shown that iron-rich sediments enhance phosphate immobilization under aerobic conditions by promoting the formation of insoluble iron-phosphate complexes [45]. In addition, microbial uptake contributed to phosphate reduction in the overlying water. Certain bacteria assimilate phosphate and store it intracellularly as polyphosphate, which supports cellular growth and reproduction [46]. The geochemical composition of the sediment plays a critical role in regulating nutrient removal and overall sMFC performance. Iron-rich sediments can enhance phosphate immobilization through the formation of iron–phosphate complexes, thereby contributing to phosphorus retention in the system [47]. Elements such as manganese (Mn), often found alongside iron, also participate in redox cycling and may compete with microbial electron transfer processes [4]. Conversely, elevated concentrations of trace metals such as lead or mercury can inhibit microbial activity and reduce the efficiency of biogeochemical reactions essential for sMFC function [48]. These sediment characteristics likely influenced both the electrochemical behavior and nutrient removal patterns observed in this study. The overall reductions in nitrate and phosphate observed across all sMFCs may also be linked to shifts in redox potential, which can accelerate organic matter degradation and promote nutrient cycling within the system. The results of this study highlight the potential of sMFCs for simultaneous nutrient removal and electricity generation. Future research should explore strategies to extend the operational lifespan of sMFCs, including using alternative electrode materials, and investigate the microbial communities involved to identify key taxa that enhance system performance. It should be noted, however, that the detected concentrations of nitrate and phosphate were substantially lower than theoretical values based on the amounts added. This discrepancy likely reflects a combination of rapid sediment adsorption, chemical precipitation, and limitations of the analytical methods used. Therefore, while the trends observed in nutrient concentrations are consistent with expected removal processes, the values should be interpreted with caution and regarded as semi-quantitative estimates.

One-way ANOVA tests showed no statistically significant differences in nitrate removal (F(2,12) = 0.49, p = 0.63) or phosphate removal (F(2,12) = 0.06, p = 0.95) among the experimental groups and the control. Despite the lack of statistical significance, Group B (1200 Ω) exhibited the highest removal rates for both nitrate and phosphate, with Group A (510 Ω) also consistently outperforming the control. The 1200 Ω condition was similarly associated with the highest power output, indirectly suggesting a potential linkage between electrical performance and nutrient removal in sMFCs. However, the high variability within groups, common in sMFC systems, likely contributed to the absence of statistically significant differences. Future studies with larger sample sizes can delve deeper into this positive relationship between electrical output and bioremediation in sMFCs. The findings of this study also highlight the potential environmental applications of sMFCs. In eutrophic ponds and rivers, sMFCs could support nutrient reduction by enhancing nitrate and phosphate removal directly within the sediment–water interface, thereby helping to mitigate algal blooms and improve water quality. On a larger scale, sMFCs may be incorporated into wastewater lagoons as low-cost, environmentally friendly bioremediation systems for nitrogen and phosphorus removal. Furthermore, sMFCs could assist sediment restoration projects by stabilizing redox conditions and reducing the release of phosphorus from contaminated sediments, promoting long-term nutrient retention and ecosystem recovery. The results of this study highlight the potential of sMFCs for simultaneous nutrient removal and electricity generation. Future research should explore strategies to extend the operational lifespan of sMFCs, including using alternative electrode materials, and investigate the microbial communities involved to identify key taxa that enhance system performance.

5. Proposed Mechanism of Nutrient Removal in the sMFC

The reductions in nitrate and phosphate observed in the overlying water appear to be driven by electrochemical and microbial processes occurring at the sediment–water interface of the sMFC. The higher external resistance (1200 Ω) generated a stronger redox gradient between the anode and cathode, which likely enhanced nitrate removal by promoting microbial nitrate reduction in the boundary zone where nitrate diffuses from the overlying water into more reducing conditions near the sediment surface, as external resistance and associated electron transfer dynamics have been shown to influence nutrient removal from overlying water in sMFC systems [39,49]. Under these conditions, denitrifying bacteria can use electrons indirectly supplied through sMFC activity to reduce nitrate to gaseous nitrogen species, a process demonstrated in sediment bioelectrochemical systems where closed-circuit sMFCs enhanced nitrate reduction in the overlying water [49] and where denitrifying exoelectrogenic bacteria in MFCs concurrently performed electricity generation and denitrification [50]. It is also possible that nitrate served as an alternative electron acceptor at the cathode when oxygen availability decreased, a mechanism previously described in sMFC studies [39,51]. Phosphate removal in the overlying water may also reflect several interacting pathways commonly reported in sMFC research. Operation of sMFCs can suppress phosphate release from sediments by creating more oxidizing conditions at the sediment surface, thereby limiting upward phosphorus flux [52,53,54]. Microbial uptake stimulated by nutrient availability may also have contributed to the decline in dissolved phosphate, as shifts in microbial activity within sMFCs can promote phosphorus assimilation into biomass [55]. In addition, pH-driven precipitation may have supported phosphate removal because proton consumption during the oxygen reduction reaction gradually increases alkalinity near the cathode, favoring the formation of insoluble phosphate minerals that settle back into the sediment. This pathway is consistent with observations from sMFC studies describing cathodic redox effects on phosphorus retention in the overlying water [39]. Although these mechanisms were not directly measured in the present study, they are well documented in the sMFC literature and provide plausible explanations for the greater nutrient removal observed under the 1200 Ω treatment.

6. Conclusions

Eutrophication remains a persistent challenge in freshwater ecosystems, yet the use of sediment microbial fuel cells (sMFCs) offers a promising dual-function approach for nutrient reduction and sustainable energy generation. In this study, sMFCs operated under a 1200 Ω external resistance produced higher voltage output and achieved greater nitrate and phosphate removal than those operated at 510 Ω, suggesting that optimal external resistance may enhance the activity of electrochemically active and denitrifying microorganisms. Although current and power density were greater at 510 Ω, the improved nutrient removal at 1200 Ω indicates that microbial processes involved in denitrification and phosphate retention may be more efficient at higher resistances.

We acknowledge that nutrient concentrations were measured using a soil-based sensor supported by colorimetric checks, and the semi-quantitative nature of these methods represents a limitation. Future work should incorporate more precise analytical tools, such as ion-selective electrodes or standard laboratory assays, to refine nutrient measurements. In addition, advanced electrochemical characterization, such as cyclic voltammetry, chronoamperometry, and detailed IV analysis, would provide deeper insight into electrode processes, internal resistance behavior, and long-term system stability. Further research is also needed to evaluate how sediment geochemistry influences electron transfer, microbial community structure, and overall sMFC performance. Techniques such as 16S rRNA sequencing would allow identification of functional microbial taxa and help clarify the relationship between community composition, electrical output, and nutrient removal. Additionally, field-based experimentation and integration of plant–microbe systems may broaden the environmental applications of sMFC technology, particularly in eutrophic ponds, wastewater lagoons, and sediment restoration projects. Although direct correlation analysis between power generation and nutrient removal was not feasible here due to mismatched sampling intervals, the 1200 Ω treatment consistently exhibited the highest performance in both areas. Future studies with synchronized measurements and larger sample sizes will be valuable for determining whether electrical output can reliably predict bioremediation efficiency. Overall, the results demonstrate the potential of sMFCs as eco-friendly, low-energy tools for improving water quality and supporting freshwater ecosystem restoration.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pollutants6010007/s1, Figure S1: Assembled sediment microbial fuel cells (sMFCs) used in the experiment.

Author Contributions

A.B. constructed the fuel cells under the guidance of W.G. W.G. planned and supervised the work. A.B. processed data and carried out the analysis. A.B., B.G., B.L., K.F. and W.G. provided necessary feedback and insight into the organization of the paper and results. A.B. and W.G. drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Mark Stephens and Jermaine Chambers for providing valuable insight into carrying out this experiment. The authors express tremendous gratitude to Monique McFarlane-Bain for her role in proofreading the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MFC | Microbial Fuel Cell |

| sMFCs | Sediment Microbial Fuel Cells |

| NPK | Nitrogen Phosphorus Potassium |

| KH2PO4 | Potassium Phosphate |

| KNO3 | Potassium Nitrate |

References

- Zhan, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, P. Rapid remediation of nitrate pollution of groundwater. J. Coast. Res. 2019, 97, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.W.G. Eutrophication. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1972, 180, 371–382. [Google Scholar]

- Karlson, B.; Andersen, P.; Arneborg, L.; Cembella, A.; Eikrem, W.; John, U.; West, J.J.; Klemm, K.; Kobos, J.; Lehtinen, S.; et al. Harmful algal blooms and their effects in coastal seas of Northern Europe. Harmful Algae 2021, 102, 101989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaskovski, B.; Petrović, M.; Kljajić, Z.; Degetto, S.; Stanković, S. Analysis of major, minor and trace elements in surface sediments by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry for assessment of possible contamination of Boka Kotorska Bay, Montenegro. Maced. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2014, 33, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rađenović, D.; Slijepčević, N.; Tomić, T.; Tenodi, S.; Krčmar, D.; Beljin, J.; Pilipović, D.T. Toward global sediment management: Lessons learned from a multidimensional risk assessment. CLEAN-Soil Air Water 2024, 53, e202300263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfahunegn, A.A.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Si, Z.; Abraha, K.G.; Mihretu, L.D. Enriched microbial fuel cells; Enhancing anode fillers to purify eutrophic water. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2023, 194, 109582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porteus, A. Microbial fuel cell. In Dictionary of Environmental Science and Technology, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Available online: https://search.credoreference.com/articles/Qm9va0FydGljbGU6MjM2Mjg2Mw==?aid=280087 (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Ida, T.K.; Mandal, B. Microbial fuel cell design, application and performance: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 76, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, B.E. Microbial Fuel Cells; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mashkour, M.; Rahimnejad, M.; Mashkour, M. Bacterial cellulose-polyaniline nano-biocomposite: A porous media hydrogel bioanode enhancing the performance of microbial fuel cell. J. Power Sources 2016, 325, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipanahi, R.; Rahimnejad, M.; Najafpour, G. Improvement of sediment microbial fuel cell performances by design and application of power management systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 16965–16975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustave, W. The Mineral-Electrogens-Electrodes System in Paddy Soils and Their Impacts on Trace Elements Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Feregrino-Rivas, M.; Ramirez-Pereda, B.; Estrada-Godoy, F.; Cuesta-Zedeño, L.F.; Rochín-Medina, J.J.; Bustos-Terrones, Y.A.; Gonzalez-Huitron, V.A. Performance of a sediment microbial fuel cell for bioenergy production: Comparison of fluvial and marine sediments. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 168, 106657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalathil, S.; Patil, S.A.; Pant, D. Microbial fuel cells: Electrode materials. In Encyclopedia of Interfacial Chemistry: Surface Science and Electrochemistry, 1st ed.; Wandelt, K., Vadgama, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, S.; Zeng, W.; Li, F. The influence of external resistance on the performance of microbial fuel cell and the removal of sulfamethoxazole wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 336, 125308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.D.; Babel, S. Unravelling and enhancing the power recovery and nitrogen removal mechanism from wastewater by isolating input nitrogen in a coupled microbial fuel cell system. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbugua, J.; Mbui, D.; Mwaniki, J.; Mwaura, F. Microbial fuel cells: Influence of external resistors on power, current and power density. J. Thermodyn. Catal. 2017, 8, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamau, J.M.; Mbui, D.N.; Mwaniki, J.M.; Mwaura, F.B. Electricity Generation from Microbial Fuel Cells Using Different External Resistors. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2017, 9, 054701. [Google Scholar]

- Koók, L.; Nemestóthy, N.; Bélafi-Bakó, K.; Bakonyi, P. The influential role of external electrical load in microbial fuel cells and related improvement strategies: A review. Bioelectrochemistry 2021, 140, 107749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N. Remediation of mariculture sediment by sediment microbial fuel cell. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 261, 04037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Yang, N.; Xu, D.; Song, C.; Liu, H. Insight into a single-chamber air-cathode microbial fuel cell for nitrate removal and ecological roles. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1397294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhou, J.; Jia, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Gong, L.; Wang, J. Effect of nitrate concentration on power generation and nitrogen removal in microbial fuel cell. Chem. Ecol. 2023, 39, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.X.H.; Bechelany, M.; Cretin, M. Carbon felt based-electrodes for energy and environmental applications: A review. Carbon 2017, 122, 564–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Su, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Bacterial community composition at anodes of microbial fuel cells for paddy soils: The effects of soil properties. J. Soils Sediments 2015, 15, 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustave, W.; Yuan, Z.F.; Sekar, R.; Ren, Y.X.; Chang, H.C.; Liu, J.Y.; Chen, Z. The change in biotic and abiotic soil components influenced by paddy soil microbial fuel cells loaded with various resistances. J. Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.H.; Zhao, G.Y.; Wang, F.Y.; Fujita, M. A simulation of acetate consumption and electricity generation in a single microbial fuel cell considering the diversity of nonelectrogenic bacteria. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 45, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potrykus, S.; León-Fernández, L.F.; Nieznański, J.; Karkosiński, D.; Fernandez-Morales, F.J. The influence of external load on the performance of microbial fuel cells. Energies 2021, 14, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, N.N.M.; Jeong, I.; Yoon, S.; Kim, K. Utilization of spent coffee grounds for bioelectricity generation in sediment microbial fuel cells. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; He, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Guo, J.; Sun, G.; Zhou, J. Responses of Aromatic-Degrading microbial communities to elevated nitrate in sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 12422–12431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.; Peixoto, L.; Teodorescu, S.; Parpot, P.; Nogueira, R.; Brito, A.G. Impact of an external electron acceptor on phosphorus mobility between water and sediments. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 151, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obileke, K.; Onyeaka, H.; Meyer, E.L.; Nwokolo, N. Microbial fuel cells, a renewable energy technology for bio-electricity generation: A mini-review. Electrochem. Commun. 2021, 125, 107003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Jimenez, P.; Martinez-Crespiera, S.; Amantia, D.; Della Pirriera, M.; Forns, I.; Shechter, R.; Borràs, E. Non-precious metal doped carbon nanofiber air-cathode for Microbial Fuel Cells application: Oxygen reduction reaction characterization and long-term validation. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 228, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cheng, S.; Logan, B.E. Power generation in fed-batch microbial fuel cells as a function of ionic strength, temperature, and reactor configuration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 5488–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paucar, N.E.; Sato, C. Microbial Fuel Cell for Energy Production, Nutrient Removal and Recovery from Wastewater: A Review. Processes 2021, 9, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeckman, F.; Motte, H.; Beeckman, T. Nitrification in agricultural soils: Impact, actors and mitigation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 50, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shen, N.; Wang, G.; Yan, Y. Realignment of phosphorus in lake sediment induced by sediment microbial fuel cells (SMFC). Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustave, W.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, F.; Chen, Z. Mechanisms and challenges of microbial fuel cells for soil heavy metal (loid) s remediation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 143865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velvizhi, G.; Mohan, S.V. In situ system buffering capacity dynamics on bioelectrogenic activity during the remediation of wastewater in microbial fuel cell. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2013, 33, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ye, C. The application of sediment microbial fuel cells in aquacultural sediment remediation. Water 2022, 14, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araneda, I.; Tapia, N.; Lizama-Allende, K.; Vargas, I.T. Constructed wetland-microbial fuel cells for sustainable greywater treatment. Water 2018, 10, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Yao, Y.; Lichtfouse, É. Improved electricity production and nitrogen enrichment during the treatment of black water using manganese ore-modified anodes. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 3387–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wang, W.; Yan, Z.; Xu, D. The Important Role of Denitrifying Exoelectrogens in Single-Chamber Microbial Fuel Cells after Nitrate Exposure. Separations 2024, 11, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, H.; Regan, J.M. Facultative nitrate reduction by electrode-respiring geobacter metallireducens biofilms as a competitive reaction to electrode reduction in a bioelectrochemical system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 3195–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, D.; Van Bogaert, G.; Diels, L.; Vanbroekhoven, K. Wastewater treatment in microbial fuel cells: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Kan, D.; Bartlett, R.; Pinay, G.; Ding, Y.; Mader, W.F. Enrichment of phosphate on ferrous iron phases during bio-reduction of ferrihydrite. Int. J. Geosci. 2012, 3, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, J. Removal of nutrients in various types of constructed wetlands. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 380, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krom, M.D.; Berner, R.A. Adsorption of phosphate in anoxic marine sediments1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1980, 25, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.Z.; Rafatullah, M.; Ismail, N.; Syakir, M. A review on sediment microbial fuel cells as a new source of sustainable energy and heavy metal remediation: Mechanisms and future prospective. Int. J. Energy Res. 2017, 41, 1242–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Xiao, E.; Wu, J.; He, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z. Enhanced nitrate reduction in water by a combined bio-electrochemical system of microbial fuel cells and submerged aquatic plant Ceratophyllum demersum. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 78, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Guo, F.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H. Enhancing the electricity generation and nitrate removal of microbial fuel cells with a novel denitrifying exoelectrogenic strain EB-1. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hou, D.; Zhang, S.; Cao, X.; Wang, H.; Li, X. Aerobic denitrification is enhanced using biocathode of SMFC in low-organic matter wastewater. Water 2021, 13, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemura, Y.; Syutsubo, K.; Kubota, K. Suppression of phosphorus release from eutrophic lake sediments by sediment microbial fuel cells. Environ. Technol. 2022, 43, 2581–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, G.L.E.P.; Maeda, M.; Somura, H.; Nakano, C.; Nishina, Y. Iron-added sediment microbial fuel cells to suppress phosphorus release from sediment in an agricultural drainage. J. Water Environ. Technol. 2023, 21, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, N.; Ni, J.; Gu, X. Enhanced phosphorus flux from overlying water to sediment in a bioelectrochemical system. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 216, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; He, Q.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Ji, X.; Guo, Y.; Hu, W.; Li, M. Organic carbon compounds removal and phosphate immobilization for internal pollution control: Sediment microbial fuel cells, a prospect technology. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 363, 125110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.