Abstract

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles (NPs) have garnered significant attention as photocatalysts for degrading organic pollutants, particularly synthetic dyes such as rhodamine B (RhB), methylene blue, methyl orange, and others. The impact of several synthesis methods, including sol–gel, hydrothermal, and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) techniques, on the electrical and morphological properties of TiO2 NPs has been studied, emphasizing the distinctive physicochemical properties of TiO2 NPs, including their extensive surface area, significant oxidative capacity, and remarkable chemical stability, which are important in the recent advancements in their use for RhB degradation. A detailed examination of TiO2’s photocatalytic mechanism shows that it is based on the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by photoinduced electron–hole pair formation under ultraviolet (UV) light exposure. In wastewater treatment, TiO2 degrades RhB into less harmful byproducts by the generation of electron–hole pairs that initiate redox reactions under sunlight. This study includes a thorough overview of significant factors influencing photocatalytic efficacy. The parameters include particle size, crystal phase (anatase, rutile, and brookite), surface changes, and the incorporation of metal or non-metal dopants to enhance visible light absorption. Researchers continually seek methods to overcome challenges, including restricted visible-light responsiveness and rapid electron–hole recombination. The investigated approaches include heterojunction generation, composite development, and co-catalyst insertion. This review article aims to address the deficiencies in our understanding of TiO2-based photocatalysis for the degradation of RhB and to propose enhancements for these systems to enable more efficient and sustainable wastewater treatment in the future.

1. Introduction

Access to pure water is recognized as a serious issue in the modern world because of quick population growth, increased water consumption, and a rise in the quantity of wastewater discharged by chemical industries. RhB is a xanthene dye and has many uses in the leather, paper, textile, and paint industries. Therefore, it is crucial to find efficient techniques for RhB degradation before it is released into the environment. Unfortunately, traditional techniques are not useful at degrading chemical compounds completely, as most chemical compounds have a high chemical stability and are not easily biodegradable [1]. Semiconductor photocatalysis has gained recognition in the last twenty years as a result of its applications to pollution control. Among various frequently used oxide semiconducting photocatalysts, TiO2 is a widely used photocatalyst, as it shows outstanding photocatalytic performance, chemical durability, inexpensiveness, and safety. Mainly, TiO2 has anatase (Eg = 3.2 eV) and rutile (Eg = 3.0 eV) crystalline phases. The anatase crystalline phase consistently shows enhanced photocatalytic performance compared to any other crystalline phase [2]. The anatase crystalline phase of TiO2 exhibits a large band gap (3.2 eV) and enhanced electron–hole separation capability throughout UV illumination. TiO2 NPs are not able to capture light with a wavelength exceeding 398 nm and show activity under UV light. Sadly, industrial-scale UV lights are expensive and have a high energy demand when it comes to implementing this method at a large scale. Under solar light, nearly 5% of sunlight consists of UV light, and pure TiO2 remains inactive. Doping TiO2 with nonmetallic species (F, S, B, and N) or transition metal species (Cu, Cs, Cr, Fe, and Au) is a significant technique that boosts light capture on the surface and enables TiO2 performance in visible light. Under optimal dosing conditions, iron ions are recognized as a high-quality dopant of TiO2 because they have the ability to enhance the total number of catalytically active sites on the TiO2 surface, decrease the rate of electron–hole pair recombination, and reduce the TiO2 band gap, as indicated in the literature [1]. Relevant research indicates that the massive energy emitted by ultrasonic-assisted cavitation is able to meet the requirements of TiO2 electron-filled band electron shift, thus causing catalytic activity comparable to the photocatalytic process. The preferential site nucleation and catalytic performance on the surface of TiO2 solid-phase particles is appropriate for catalytic decomposition of toxic organic species [3].

2. Mechanism

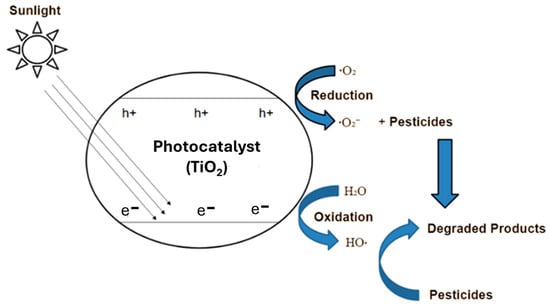

Photocatalytic oxidation using semiconductor materials like TiO2 is a light-induced process that involves the generation of reactive species capable of degrading organic pollutants and microorganisms. As the photocatalyst is exposed to UV light, its electrons become excited, creating electron–hole pairs that migrate to the surface (Figure 1). The holes react with hydroxide ions or adsorbed water and produce very reactive hydroxyl radicals, which are powerful, non-selective oxidants responsible for breaking down a wide range of organic contaminants. Simultaneously, the excited electrons reduce oxygen molecules on the catalyst surface, forming superoxide radicals. These radicals not only participate in further oxidation reactions but also help prevent reassociation of the charge transporters and maintain the performance of the process. The superoxide radicals can then undergo a series of reactions to generate additional reactive oxygen radicals, particularly hydrogen peroxide and hydroperoxyl radicals, which further decompose into more hydroxyl radicals. Together, these reactive species contribute to the full decomposition of organic contaminants and the neutralization of microbes, making the entire photocatalytic system highly effective for environmental remediation applications [4,5].

Figure 1.

Photocatalytic degradation of RhB.

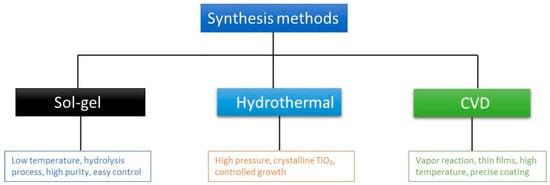

3. Synthesis Methods

In the sol–gel method, titanium alkoxide precursors like titanium (IV) n-butoxide (TNBT) or titanium isopropoxide (TTIP) are mixed with alcohol-based solvents with continuous stirring, followed by the dropwise mixing in of acidified liquid water to initiate hydrolysis and condensation reactions, forming a TiO2 sol (Figure 2). After aging, the sol transitions into a gel, which can be dried to obtain xerogel in the form of a powder, dense ceramic, or fibers. Additives such as complexing agents or metal salts can be incorporated to enhance the material’s properties based on the intended application [6]. The sol–gel technique is highly flexible and enables accurate control over NP characteristics [7]. TiO2 NPs were synthesized via hydrothermal synthesis under an applied magnetic field. Fifty milliliters of a 0.1 M TTIP mixture was placed inside a low-temperature water bath until a temperature range of 3–5 °C was reached. Subsequently, 5.0 M KOH was incrementally mixed into the low-temperature solution until a pH of 7.0 was reached. The resulting mixture was subsequently placed into a Teflon autoclave and placed under a temperature of about 160 °C for 5 h. Then, the chemical mixture was exposed to a magnetic field. The resulting powder was dried overnight in the oven and subsequently thermally treated in air at a temperature of 500 °C for 30 min, with a heating rate of 5 °C/min [8]. Photocatalytic TiO2 thin films were deposited using a vertical low-pressure CVD reactor designed as a custom cold-wall system. The titanium and oxygen sources were TTIP and oxygen gas (O2), respectively. The deposition temperature was varied between 287 °C and 362 °C, while the operating pressure was maintained at 1 Torr. Argon was employed as the carrier gas for TTIP, with flow rates of 80 cm3·min−1 for Ar and 10 cm3·min−1 for O2. The TTIP delivery rate was maintained at 4.464 × 10−5 mol·min−1. The microstructural properties of the deposited TiO2 films were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using Cu Kα radiation operated at 40 kV and 20 mA. The surface morphology and cross-sectional structures of the films were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The photocatalytic degradation of benzene was evaluated using 10 × 10 cm2 TiO2-coated glass substrates placed in a quartz reactor with an internal volume of 610 mL. The experiments were carried out under UV illumination (Sankyo BLB lamp, λ = 365 nm) with an intensity of 0.71 mW·cm−2 at ambient temperature. The initial benzene concentration in the reactor was approximately 120 ppm.

Figure 2.

Various synthesis methods.

The degradation products were analyzed via gas chromatography (HP6890 series) under constant-flow conditions. The operational parameters were maintained at a pressure of 18.5 psi, a helium flow rate of 0.9 mL·min−1, and an average linear velocity of 29 cm·s−1 [9].

4. Key Factors Influencing Photocatalysis

Particle size plays a critical role in determining the effectiveness of nano-photocatalytic materials. The dimensions and configuration of the catalyst affect its catalytic performance and surface structure [10,11]. Tiny particles of the photoactive material enhance the yields of products as compared to the bulk particles [12]. In contrast to bulk titanium dioxide, granular TiO2 NPs exhibit an increased surface area and an expanded band gap. Their composition includes a greater number of active sites, leading to enhanced photocatalytic activity, superior photoelectrochemical properties, and increased gas sensitivity [13,14]. Rutile represents the stable phase, while anatase and brookite are considered metastable and can convert to rutile upon heating [15]. Rutile by itself has hardly ever been found to be active for the photodegradation of organic compounds in aqueous solutions, but satisfactory levels of photocatalytic activity have been exhibited by samples containing mixtures of anatase and rutile [16,17]. In contrast, brookite has received relatively little attention as a photocatalyst, mainly because obtaining it in pure form is quite challenging [18]. High anatase crystallinity and large crystallite size mean low surface energy, and a low surface energy is unfavorable for the phase transformation process, consequently leading to an enhancement in the initial phase transformation temperature [2]. Owing to the large surface area of NP-based semiconductor systems and the sufficient spectrum property of the standard dyes, the integrated systems may capture a high percentage of the incoming solar radiation, as high as 46%. However, efficiencies achieved in simulated sunlight in an AM 1.5 environment are comparatively low, approximately 7–11% [19]. It is expected that in light-assisted catalysis, the adsorption of hazardous compounds ahead of time is a key step [20]. Thus, high surface area is a crucial factor in enhancing the light-assisted activity of TiO2. It is suggested that large surface area and high-quality anatase crystals are vital for effective photocatalytic activity [2]. The ionic interactions between the surface of the catalyst, radicals, and substrates during the decomposition process are determined by the pH of the contaminated water containing organic dye. If the pH is lower than 2, then TiO2 shows strong oxidation [21]. If the pH is less than 5, dye photodegradation can be stopped by excess proton concentration, reducing efficiency. On the other hand, if the pH is more than 10, hydroxyl ions can neutralize acidic products produced by photocatalytic degradation [22].

5. Challenges

TiO2 photocatalysts have some problems, including limited sunlight utilization, poor reaction efficiency, and ineffective treatment of concentrated wastewater [3]. The anatase form of TiO2 possesses a wide band gap of approximately 3.2 eV and experiences a high rate of electron–hole recombination under UV irradiation. TiO2 particles are unable to absorb light with wavelengths exceeding 398 nm and therefore exhibit photocatalytic activity solely in the UV region [1]. Furthermore, TiO2 has a large band gap, and it can use only UV light for H2 production. UV light accounts for fewer than 5% of the solar spectrum, and visible light contributes approximately 50%. H2 production may decrease if visible light is not deployed [23]. However, the multiple-step electron energy exchange process in the photocatalysis process is a longstanding challenge, and it should be solved [24]. In addition, extra charges, surface additives such as metals or metal oxides, and the states of adsorbed species play crucial roles in the photocatalysis process. These elements open chances to explore model systems and increase challenges in finding significant insights into the basic process of TiO2 photocatalysis [25].

6. Result

Natarajan et al. synthesized UV-LED/TiO2 NPs with a 30 nm size in order to apply them in the degradation of RhB dye and found 96% efficiency after 180 min [26]. Slimani et al. prepared Ce and Sm co-doped TiO2 NPs with a 15.1–17.8 nm size for RhB degradation to achieve 98% removal efficiency in 30 min [27]. Abdel-Messih et al. developed SnO2/TiO2 NPs with a size of 19 nm and achieved 92% efficiency within 189 min [28]. Ruíz-Santoyo et al. formulated TiO2-ZrO2 as NPs of 10.1 nm exhibiting 84.6% RhB removal after 150 min [29]. Indira et al. constructed 2.28 nm Ce-TiO2 NPs that removed 95% RhB after 100 min [30]. Safajou et al. engineered Pd/TiO2 NPs with a 50 nm size that removed 76% of RhB within 40 min [31]. Wang et al. obtained RGO–TiO2 NPs of 5 nm that could degrade RhB with an efficiency rate of 86% after 5 h [32]. Karimi et al. found 20–30 nm TFNA/TiO2 NPs were 86% efficient in RhB removal after 100 min [33]. Gatou et al. synthesized 1.82 nm TiO2/SiO2 NPs that degraded 100% of RhB after 210 min [34]. Malika et al. generated 20 and 30 nm Cu-Ni (75:25)-TiO2/MMT NPs that achieved 97% degradation efficiency after 50 min [35]. Baruah et al. processed GO/PANI/15%TiO2 NPs of 15.91 nm, which degraded 98% of RhB within 80 min [36]. Mekprasart et al. yielded CuPc/TiO2 NPs with a 20–30 nm size and achieved 87.5% efficiency after 35 min [37]. Ali et al. found that TiO2@rGo NPs of 25 nm could degrade 96% of RhB within 60 min [38]. Mufti et al. fabricated Fe3O4@TiO2 NPs with a size of 38.5–72.8 nm, degrading 67.7% of RhB within 120 min [39]. Rasalingam et al. synthesized Ti-HTS-240 of 12 nm, which degraded more than 97% of RhB within 180 min [40].

7. Conclusions

It can be seen that the best synthesis method for TiO2 NPs is sol–gel. Sol–gel, CVD, and hydrothermal are a few of the main approaches, but the sol–gel method has superior control over crystallinity, size of particles, and surface area. The reviewed literature shows that doping and heterojunction formation can enhance the degradation rate of RhB. Controlled synthesis and tuning by surface engineering of TiO2 NPs will be useful for energy-efficient and sustainable photocatalytic systems for RhB degradation.

8. Strategies to Overcome Challenges

Adding QAD molecules to the TiO2 surface causes a two-fold improvement in the photoactivity of the QAD/TiO2 nano-heterostructure in comparison with undoped TiO2 NPs, and QAD/TiO2 achieved nearly complete photocatalytic degradation (~98%) of RhB dye within 3 h under only UV-A light irradiation [41]. Now, doping with non-metallic elements, such as S, C, and N, is receiving a lot of research interest. Researchers showed that the p atomic orbitals of these elements considerably overlap with the band of valence electrons of O 2p-orbitals, which helps the movement of light-induced charge particles to the surface of the catalytic material [42]. When In2O3 and TiO2 are closely combined with each other under photoexcitation, the photoinduced electrons from In2O3 will efficiently move to the excited-state band of TiO2, while the holes in TiO2 will quickly migrate to the valence electronic band of In2O3. This action will obviously promote the detachment of the charge carriers and produce the generation of many light-sensitive ·OH free radicals throughout the decomposition procedure, which are the main reactive particles for enhancing the light-induced decomposition [43]. Normally, crystal facets with a large surface energy display a high light-driven activity due to their strong affinity, effective electron/hole partition, and rich reactive active sites. It is a practical approach to increase the photocatalytic activity at the atomic scale, forming a strongly reactive crystal facet. For example, it has been broadly confirmed that the (001) facets of anatase TiO2 photoactive catalysts display improved photocatalytic performance compared to the other facets because of the high proportion of reactive, not saturated, pentacoordinated Ti atom (Ti5c) sites, which show a high tendency for reactants. Integrating photoactive semiconductors in combination with co-catalysts efficiently adjusts electronic band structure, improves surface electron transfer, and provides more reactive sites. This is another path to enhancing photoactive characteristic semiconductor compounds. For photocatalytic CO2 reduction, H2 evolution, and carbon-based pollutant decomposition, noble metals are commonly used as co-catalysts to pave the way. When combining noble metals with a semiconductor, a Schottky barrier is created at the surface between the noble metals and the semiconductor due to their high work function, enabling the interfacial transfer of charge. The photoexcited electrons move to the surface of noble metal NPs and participate in the reduction reaction because the semiconductor is irradiated by light. Meanwhile, the generated holes migrate to the surface, where they participate in photocatalytic oxidation reactions. Consequently, incorporating a noble metal co-catalyst into the semiconductor can promote charge separation and enhance photocatalytic performance [44].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I.H.; writing—original abstract, A.I.H.; writing—original draft (introduction), M.G.S.; writing—original draft (conclusion), M.G.S.; wrote—original draft (without abstract, introduction, conclusion), H.R.; writing—review, M.G.S.; writing—editing, M.R.R.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Isari, A.A.; Payan, A.; Fattahi, M.; Jorfi, S.; Kakavandi, B. Photocatalytic degradation of rhodamin B and real textile wastewater using Fe-doped TiO2 anchored on reduced graphene oxide (Fe-TiO2/rGO): Characterization and feasibility, mechanism and pathway studies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 462, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Jing, L.; Zhou, J.; Lin, J.; Fu, H. Synthesis of nanocrystalline anatase TiO2 by one-pot two-phase separated hydrolysis-solvothermal processes and its high activity for photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 176, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Ma, H. Degradation of rhodamine B in water by ultrasound-assisted TiO2 photocatalysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.R.; Martin, S.T.; Choi, W.; Bahnemann, D.W. Environmental Applications of Semiconductor Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peral, J.; Domènech, X.; Ollis, D.F. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis for Purification, Decontamination and Deodorization of Air. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. Int. Res. Process Environ. Clean Technol. 1997, 70, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Rad, S.; Gan, L.; Li, Z.; Dai, J.; Shahab, A. Reviw of the sol-gel method in preparing nano TiO2 for advanced oxidation process. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2023, 12, 20230150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avasarala, B.K.; Tirukkovalluri, S.R.; Bojja, S. Magnesium Doped Titania for Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes in Visible Light. J. Environ. Anal. Toxicol. 2016, 6, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, H.G.; Abdulrahman, N.A. Synthesis of TiO2 Nanoparticles by Hydrothermal Method and Characterization of their Antibacterial Activity: Investigation of the Impact of Magnetism on the Photocatalytic Properties of the Nanoparticles. Phys. Chem. Res. 2023, 11, 771–782. [Google Scholar]

- Byun, D.; Jin, Y.; Kim, B.; Lee, J.K.; Park, D. Photocatalytic TiO2 deposition by chemical vapor deposition. J. Hazard. Mater. 2000, 73, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Tao, F.F.; Tang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, J. Size- and shape-dependent catalytic performances of oxidation and reduction reactions on nanocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 4747–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.J.; Yang, S.; Lee, H. Surface analysis of N-doped TiO2 nanorods and their enhanced photocatalytic oxidation activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 204, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.; Lin, C. Effect of particle size of titanium dioxide nanoparticle aggregates on the degradation of one azo dye. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Zhao, Z.; Kumar, A.; Boughton, R.I.; Liu, H. Recent progress in design, synthesis, and applications of one-dimensional TiO2 nanostructured surface heterostructures: A review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6920–6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, C.L.; Gatto, S.; Pirola, C.; Naldoni, A.; Michele, A.D.; Cerrato, G.; Crocellà, V.; Capucci, V. Photocatalytic degradation of acetone, acetaldehyde and toluene in gas-phase: Comparison between nano- and micro-sized TiO2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 146, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdjoub, N.; Allen, N.; Kelly, P.; Vishnyakov, V. Thermally induced phase and photocatalytic evolution of polymorphous titania. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2010, 210, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Li, S.; Song, S.; Xue, L.; Fu, H. Investigation on the electron transfer between anatase and rutile in nano-sized TiO2 by means of surface photovoltage technique and its effects on the photocatalytic activity. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2008, 92, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersani, D.; Antonioli, G.; Lottici, P.P.; Lopez, T. Raman study of nanosized titania prepared by sol–gel route. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1998, 232, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.S.; Mahdjoub, N.; Vishnyakov, V.; Kelly, P.J.; Kriek, R.J. The effect of crystalline phase (anatase, brookite and rutile) and size on the photocatalytic activity of calcined polymorphic titanium dioxide (TiO2). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 150, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libanori, R.; Giraldi, T.R.; Longo, E.; Leite, E.R.; Ribeiro, C. Effect of TiO2 surface modification in Rhodamine B photodegradation. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2009, 49, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhan, M.A.; Choudhury, K.P.; Neogi, N. Advances with Molecular Nanomaterials in Industrial Manufacturing Applications. Nanomanufacturing 2021, 1, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, H.; Mahmood, A.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.H.; Park, J.; Yip, A.C.K. Photocatalysts for degradation of dyes in industrial effluents: Opportunities and challenges. Nano Res. 2019, 12, 955–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, K.M.; Kurny, A.; Gulshan, F. Parameters affecting the photocatalytic degradation of dyes using TiO2: A review. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.; Zafar, M. Titanium dioxide nanostructures as efficient photocatalyst: Progress, challenges and perspective. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 3569–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhan, M.A.; Neogi, N.; Choudhury, K.P. Industrial Manufacturing Applications of Zinc Oxide Nanomaterials: A Comprehensive Study. Nanomanufacturing 2022, 2, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhou, C.; Ma, Z.; Yang, X. Fundamentals of TiO2 photocatalysis: Concepts, mechanisms, challenges. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1901997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, T.S.; Thomas, M.; Natarajan, K.; Bajaj, H.C.; Tayade, R.J. Study on UV-LED/TiO2 process for degradation of Rhodamine B dye. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 169, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimani, Y.; Almessiere, M.A.; Mohamed, M.J.S.; Hannachi, E.; Caliskan, S.; Akhtar, S.; Baykal, A.; Gondal, M.A. Synthesis of Ce and Sm Co-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity for Rhodamine B Dye Degradation. Catalysts 2023, 13, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Messih, M.F.; Ahmed, M.A.; El-Sayed, A.S. Photocatalytic decolorization of Rhodamine B dye using novel mesoporous SnO2–TiO2 nano mixed oxides prepared by sol–gel method. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2013, 260, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruíz-Santoyo, V.; Marañon-Ruiz, V.F.; Romero-Toledo, R.; Vargas, O.A.G.; Pérez-Larios, A. Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B and Methylene Orange Using TiO2-ZrO2 as Nanocomposite. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indira, A.C.; Muthaian, J.R.; Pandi, M.; Mohammad, F.; Al-Lohedan, H.A.; Soleiman, A.A. Photocatalytic Efficacy and Degradation Kinetics of Chitosan-Loaded Ce-TiO2 Nanocomposite towards for Rhodamine B Dye. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1506. [Google Scholar]

- Safajou, H.; Khojasteh, H.; Salavati-Niasari, M.; Mortazavi-Derazkola, S. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of dyes over graphene/Pd/TiO2 nanocomposites: TiO2 nanowires versus TiO2 nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 498, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, K. Reduced graphene oxide–TiO2 nanocomposite with high photocatalystic activity for the degradation of rhodamine B. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2011, 345, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Grayeli, A.R. Synthesis and Characterization of Nonmetal-doped TiO2 Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B Dye. Prog. Color Color. Coat. 2024, 17, 263–273. [Google Scholar]

- Gatou, M.A.; Fiorentis, E.; Lagopati, N.; Pavlatou, E.A. Photodegradation of Rhodamine B and Phenol Using TiO2/SiO2 Composite Nanoparticles: A Comparative Study. Water 2023, 15, 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malika, M.; Sonawane, S.S. Statistical modelling for the Ultrasonic photodegradation of Rhodamine B dye using aqueous based Bi-metal doped TiO2 supported montmorillonite hybrid nanofluid via RSM. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 44, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, S.; Kumar, S.; Nayak, B.; Puzari, A. Optoelectronically suitable graphene oxide-decorated titanium oxide/polyaniline hybrid nanocomposites and their enhanced photocatalytic activity with methylene blue and rhodamine B dye. Polym. Bull. 2021, 78, 1703–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekprasart, W.; Vittayakorn, N.; Pecharapa, W. Ball-milled CuPc/TiO2 hybrid nanocomposite and its photocatalytic degradation of aqueous Rhodamine B. Mater. Res. Bull. 2012, 47, 3114–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.H.; Al-Afify, A.D.; Goher, M.E. Preparation and characterization of graphene—TiO2 nanocomposite for enhanced photodegradation of Rhodamine-B dye. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2018, 44, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mufti, N.; Munfarriha, U.; Fuad, A.; Diantoro, M. Synthesis and photocatalytic properties of Fe3O4@TiO2 core-shell for degradation of Rhodamine B. AIP Conf. Proc. 2016, 1712, 050009. [Google Scholar]

- Rasalingam, S.; Wu, C.M.; Koodali, R.T. Modulation of Pore Sizes of Titanium Dioxide Photocatalysts by a Facile Template Free Hydrothermal Synthesis Method: Implications for Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 4368–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel-Hamza, M.; Rizk, S.A.; Ezz-Elregal, E.E.M.; El-Rahman, S.A.A.; Ramadan, S.K.; Abou-Gamra, Z.M. Photosensitization of TiO2 microspheres by novel Quinazoline-derivative as visible-light-harvesting antenna for enhanced Rhodamine B photodegradation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Cao, C.; Erickson, L.; Hohn, K.; Maghirang, R.; Klabunde, K. Photo-catalytic degradation of Rhodamine B on C-, S-, N-, and Fe-doped TiO2 under visible-light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 91, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Tan, Z.; Wang, C.; Yang, X.; Zhang, G.; Pan, H. Fabrication of In2O3/TiO2 nanotube arrays hybrids with homogeneously developed nanostructure for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018, 106, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Tao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Bian, Z.; Li, H. Challenges of photocatalysis and their coping strategies. Chem Catal. 2022, 2, 1315–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).