Utilization of TiO2 Nanoparticles for Methylene Blue Degradation †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis Methods

2.2. Photocatalytic Activity Test

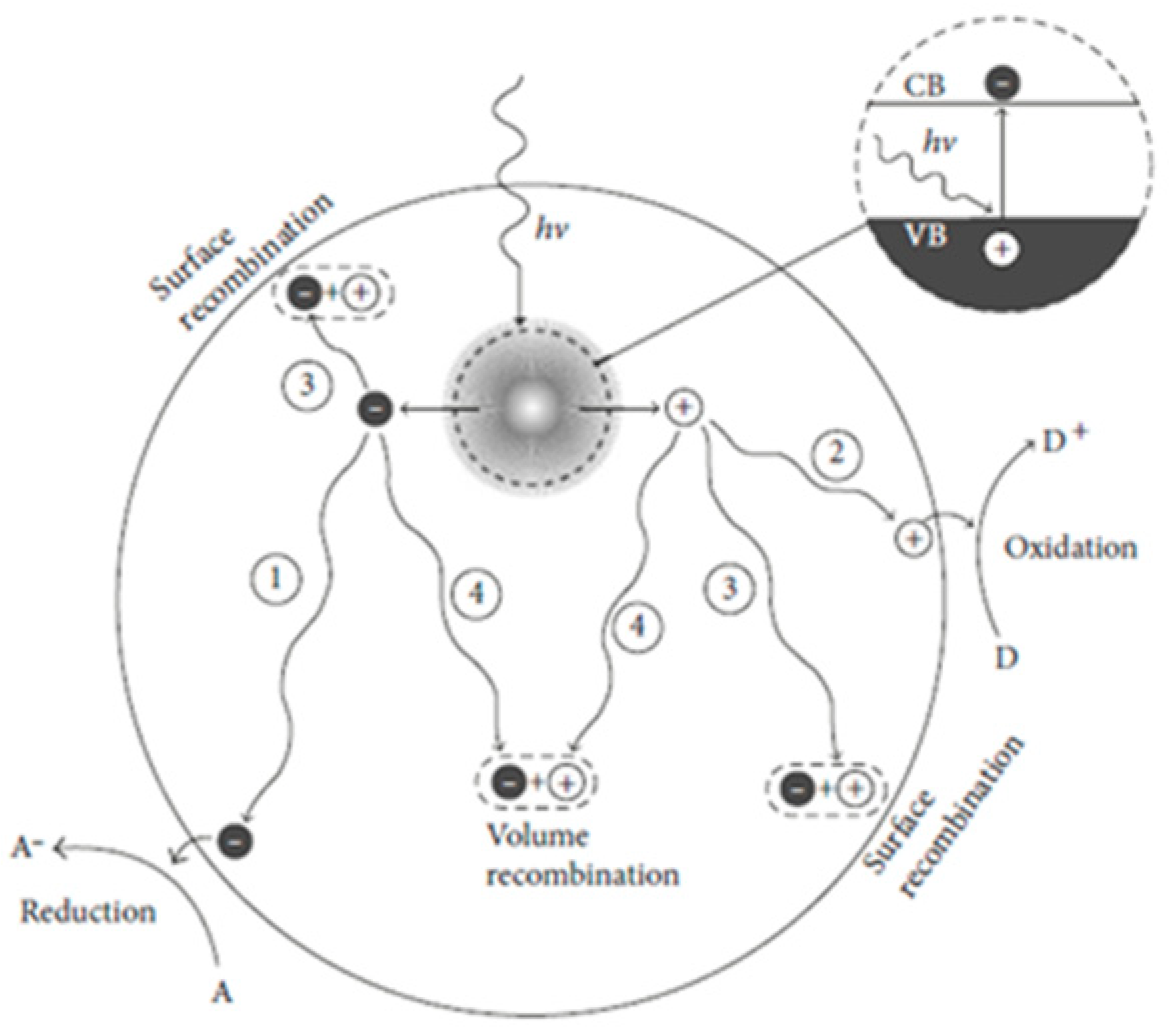

3. Photocatalytic Mechanism in TiO2

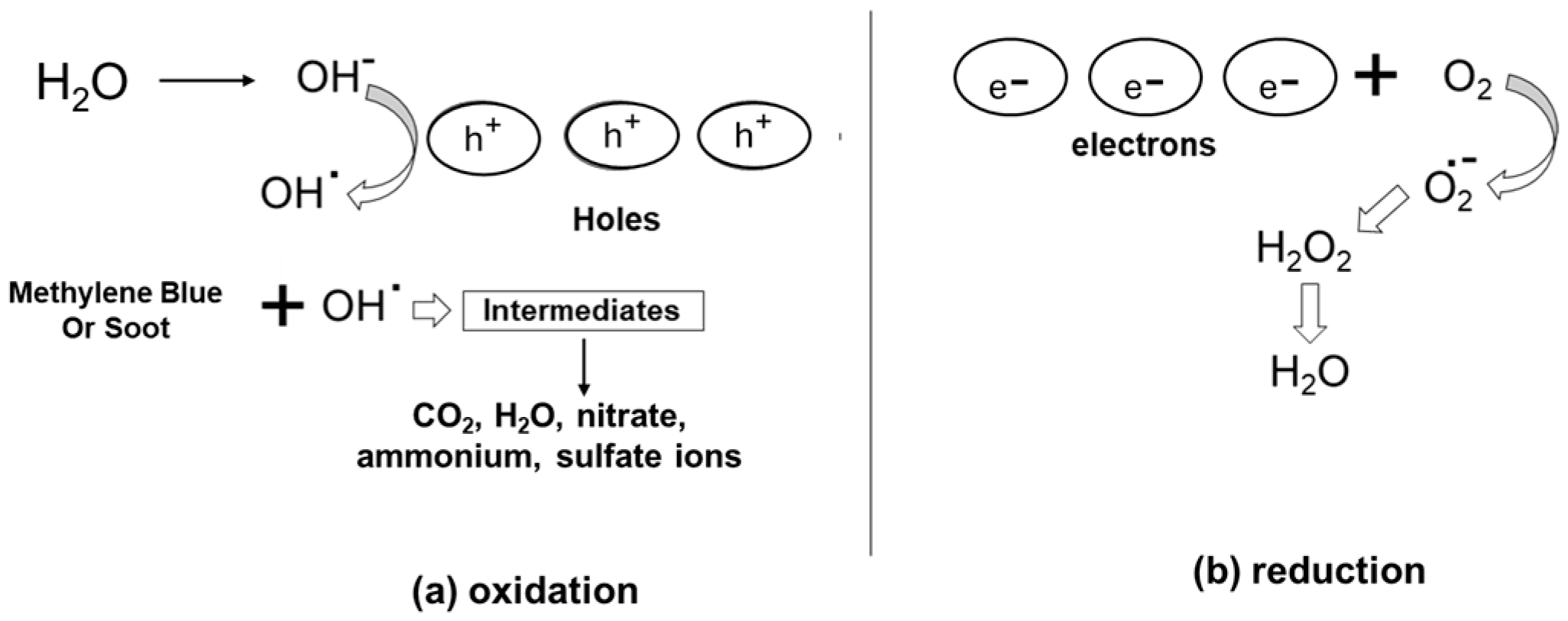

4. Electrons and Holes Participate in Redox Process

5. Parameters of TiO2 NPs Influencing Photocatalytic Activity

6. Active Sites and Recombination Rates in TiO2 Photocatalysis

7. Disadvantages of TiO2 as a Photocatalyst

8. Improvements in TiO2 NPs’ Photocatalytic Activity

9. Strategies to Overcome Challenges

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Govindhan, P.; Pragathiswaran, C.; Chinnadurai, M. A Magnetic Fe3O4 Decorated TiO2 Nanoparticles Application for Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue (MB) under Direct Sunlight Irradiation. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 6458–6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhan, M.A.; Choudhury, K.P.; Neogi, N. Advances with molecular nanomaterials in industrial manufacturing applications. Nanomanufacturing 2021, 1, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Gamra, Z.M.; Ahmed, M.A. Synthesis of Mesoporous TiO2–Curcumin Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 160, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; El-Katori, E.E.; Gharni, Z.H. Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye Using Fe2O3/TiO2 Nanoparticles Prepared by Sol–Gel Method. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 553, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Mohammadizadeh, M.R. Simultaneous Improvement of Photocatalytic and Superhydrophilicity Properties of Nano TiO2 Thin Films. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2012, 90, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchak, N.M.; Deshpande, M.P.; Mistry, H.M.; Pandya, S.J.; Chaki, S.H.; Bhatt, S.V. Kinetic Study of Adsorption and Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye Using TiO2 Nanoparticles with Activated Carbon. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 0659d6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.C.; Lin, H.J.; Yang, T.S. Characteristics and Optical Properties of Iron Ion (Fe3+)-Doped Titanium Oxide Thin Films Prepared by a Sol–Gel Spin Coating. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 473, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coba, A.J.O.; Briceño, S.; Vizuete, K.; Debut, A.; González, G. Diatomite with TiO2 Nanoparticles for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Carbon Trends 2025, 19, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Zekker, I.; Zhang, B.; Hendi, A.H.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, S.; Zada, N.; Ahmad, H.; Shah, L.A.; et al. Review on Methylene Blue: Its Properties, Uses, Toxicity and Photodegradation. Water 2022, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reduction of Methylene Blue by Using Direct Continuous Ozone. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 10, 46–56. [CrossRef]

- Jawad, N.H.; Najim, S.T. Removal of Methylene Blue by Direct Electrochemical Oxidation Method Using a Graphite Anode. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 454, 012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhan, M.A.; Neogi, N.; Choudhury, K.P. Industrial Manufacturing Applications of Zinc Oxide Nanomaterials: A Comprehensive Study. Nanomanufacturing 2022, 2, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Rad, S.; Gan, L.; Li, Z.; Dai, J.; Shahab, A. Review of the Sol–Gel Method in Preparing Nano TiO2 for Advanced Oxidation Process. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2023, 12, 20230150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghrib, S.; Gherdaoui, C.E.; Belgherbi, O.; Benaskeur, N.; Boudissa, M.; Kanagaraj , A.; Aouffa , N. Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Using TiO2 Nanoparticles Synthesized via the Sol–Gel Method in Acidic and Neutral Media. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2025, 138, 1725–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastan, D.; Chaure, N.; Kartha, M. Surfactants Assisted Solvothermal Derived Titania Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Simulation. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 7784–7796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Kumar Prasad, A.; Benoy, T.; Rakesh, P.P.; Hari, M.; Libish, T.M.; Radhakrishnan, P.; Nampoori, V.P.N.; Vallabhan, C.P.G. UV-Visible Photoluminescence of TiO2 Nanoparticles Prepared by Hydrothermal Method. J. Fluoresc. 2012, 22, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhoshkumar, T.; Rahuman, A.A.; Jayaseelan, C.; Rajakumar, G.; Marimuthu, S.; Kirthi, A.V.; Velayutham, K.; Thomas, J.; Venkatesan, J.; Kim, S.-K. Green Synthesis of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Using Psidium Guajava Extract and Its Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014, 7, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-K.; Okada, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Lee, S.-W. Top-Down Synthesis and Deposition of Highly Porous TiO2 Nanoparticles from NH4TiOF3 Single Crystals on Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene Oxides. Mater. Des. 2016, 108, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggerty, J.E.S.; Schelhas, L.T.; Kitchaev, D.A.; Mangum, J.S.; Garten, L.M.; Sun, W.; Stone, K.H.; Perkins, J.D.; Toney, M.F.; Ceder, G.; et al. High-Fraction Brookite Films from Amorphous Precursors. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisitsoraat, A.; Tuantranont, A.; Comini, E.; Sberveglieri, G.; Wlodarski, W. Characterization of N-Type and p-Type Semiconductor Gas Sensors Based on NiOx Doped TiO2 Thin Films. Thin Solid Films 2009, 517, 2775–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Pillai, S.C.; Falaras, P.; O’Shea, K.E.; Byrne, J.A.; Dionysiou, D.D. New Insights into the Mechanism of Visible Light Photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 2543–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Li, Y.; Xia, T. Black Titanium Dioxide Nanomaterials in Photocatalysis. Int. J. Photoenergy 2017, 2017, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahurul Islam, M.; Amaranatha Reddy, D.; Han, N.S.; Choi, J.; Song, J.K.; Kim, T.K. An Oxygen-Vacancy Rich 3D Novel Hierarchical MoS2/BiOI/AgI Ternary Nanocomposite: Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity through Photogenerated Electron Shuttling in a Z-Scheme Manner. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 24984–24993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, C.V.; Ung, F.; Zárate, J.; Cortés, J.A. Evaluation of Surface Phenomena Involved in Photocatalytic Degradation of Acid Blue 9 by TiO2 Catalysts of Single and Mixed Phase—A Theoretical and Experimental Study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 508, 145114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dariani, R.S.; Esmaeili, A.; Mortezaali, A.; Dehghanpour, S. Photocatalytic Reaction and Degradation of Methylene Blue on TiO2 Nano-Sized Particles. Optik 2016, 127, 7143–7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayade, R.J.; Surolia, P.K.; Kulkarni, R.G.; Jasra, R.V. Photocatalytic Degradation of Dyes and Organic Contaminants in Water Using Nanocrystalline Anatase and Rutile TiO2. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2007, 8, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianati, R.A.; Mengelizadeh, N.; Zazouli, M.A.; Yazdani Cherati, J.; Balarak, D.; Ashrafi, S. Photocatalytic Degradation of Bisphenol A by GO-TiO2 Nanocomposite under Ultraviolet Light: Synthesis, Effect of Parameters and Mineralisation. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2024, 104, 5065–5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnajady, M.; Modirshahla, N.; Hamzavi, R. Kinetic Study on Photocatalytic Degradation of C.I. Acid Yellow 23 by ZnO Photocatalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 133, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Calebe, V.C.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Lei, Y. Interstitial N-Doped TiO2 for Photocatalytic Methylene Blue Degradation under Visible Light Irradiation. Catalysts 2024, 14, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Jia, Y.; Chen, X.; Han, H.; Li, C. Titanium Dioxide-Based Nanomaterials for Photocatalytic Fuel Generations. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9987–10043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Carmona, A.J.; Mora, E.S.; Flores, J.I.P.; Márquez-Beltrán, C.; Castañeda-Antonio, M.D.; González-Reyna, M.A.; Barrera, M.C.; Misaghian, K.; Lugo, J.E.; Toledo-Solano, M. Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue by Magnetic Opal/Fe3O4 Colloidal Crystals under Visible Light Irradiation. Photochem 2023, 3, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sazid, M.G.; Rashid, H.; Rashid Nafi, M.R.; Helal, A.I. Utilization of TiO2 Nanoparticles for Methylene Blue Degradation. Mater. Proc. 2025, 25, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025025013

Sazid MG, Rashid H, Rashid Nafi MR, Helal AI. Utilization of TiO2 Nanoparticles for Methylene Blue Degradation. Materials Proceedings. 2025; 25(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025025013

Chicago/Turabian StyleSazid, Md. Golam, Harunur Rashid, Md. Redwanur Rashid Nafi, and Asraf Ibna Helal. 2025. "Utilization of TiO2 Nanoparticles for Methylene Blue Degradation" Materials Proceedings 25, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025025013

APA StyleSazid, M. G., Rashid, H., Rashid Nafi, M. R., & Helal, A. I. (2025). Utilization of TiO2 Nanoparticles for Methylene Blue Degradation. Materials Proceedings, 25(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025025013