Abstract

Monitoring women’s health during the menstrual cycle is crucial. Traditional methods for estimating ovulation dates involve measuring body temperature and analyzing blood, urine, cervical mucus, or saliva. While effective, these methods come with various advantages and limitations. Therefore, we introduce a novel approach to more easily and accurately detect both the menstrual period and the ovulation date. After gathering essential physiological data from test subjects, the ovulation date is predicted. Heart rate waveform signals are used to identify physiological parameters linked to ovulation, enhancing prediction accuracy without relying on consumable items such as test strips or patches. By integrating non-invasive image signal processing technology and heart rate variability analysis algorithms, the timing of ovulation within the menstrual cycle is accurately predicted.

1. Introduction

A complex and close relationship exists between the autonomic nervous system and female hormone secretion. Imbalances in female hormones are considered a significant factor contributing to autonomic nervous system instability. Among various hormones, sex hormones are particularly noteworthy due to the crucial roles they play at different stages of a woman’s life. For example, estrogen levels dramatically increase during puberty and significantly decrease during menopause. Furthermore, estrogen secretion exhibits regular fluctuations throughout the menstrual cycle and irregular changes during pregnancy and lactation. Progesterone, another key female hormone, also fluctuates during the menstrual cycle. The complex balance of female sex hormones is susceptible to disruption by multiple factors. This is particularly evident during puberty, pregnancy, lactation, and menopause when hormone fluctuations are more pronounced, consequently impacting the stability of the autonomic nervous system [1,2].

Previous research results have indicated that menstrual cycle-related headaches in women are associated with autonomic dysfunction resulting from hormonal imbalances. They are also attributed to disruptions in cerebral blood circulation caused by uterine contractions during menstruation. Additionally, progesterone can induce brain swelling, potentially contributing to headaches. Concurrently, common menstrual symptoms such as nausea and vomiting are thought to be manifestations of gastric contractions triggered by autonomic and hormonal imbalances. Furthermore, fatigue and excessive sleepiness during menstruation are also potentially linked to autonomic dysfunction. On the other hand, significant hormonal fluctuations before the menstrual cycle, along with progesterone-induced brain swelling, can lead to anxiety and irritability in women. It is important to note that the female body possesses a unique hormonal cyclicity. The central regulatory hub for this cyclicity is the pituitary gland, which also serves as the center of the autonomic nervous system. Consequently, changes in hormone levels can impact the autonomic nervous system [1].

Moreover, when individuals encounter stimuli or stress, sympathetic nervous system activity increases, leading to physiological and psychological tension. Conversely, when adaptability or stress-coping abilities are strong, parasympathetic activity is enhanced, promoting relaxation. In everyday life, psychological stimuli like interpersonal relationships and stressful events are prevalent. Furthermore, abrupt changes in environmental conditions cause imbalances in the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, resulting in autonomic dysfunction. Several women experience premenstrual syndrome around their menstrual cycles or develop autonomic dysfunction during menopause due to estrogen instability. Because the control centers for both female hormones and the autonomic nervous system are located in the hypothalamus, there is a mutual influence. Therefore, when female hormones are imbalanced, autonomic dysfunction is likely to follow [2].

The interactive relationship between the autonomic nervous system and female hormones is well established. While attending to women’s menstrual health, it is also crucial to assess individual autonomic nervous system activity and stability. In this study, the appropriate utilization of heart rate variability (HRV) technology is used to develop a useful method for women’s health in menstrual cycles and evaluate autonomic nervous system function.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related studies and key theoretical foundations. Section 3 describes the proposed system architecture, including data acquisition, signal processing techniques, and physiological index calculation. Section 4 presents experimental results based on extensive physiological data collection and evaluation. Section 5 concludes this study with the contributions and future research directions.

2. Related Works

2.1. Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Detection

The female menstrual cycle is not only a manifestation of reproductive function but also a crucial indicator of overall health. The regularity of the menstrual cycle, the amount of menstrual flow, and the severity of dysmenorrhea are key factors in assessing a woman’s health status. Although the menstrual cycle is mainly regulated by female hormones such as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and progesterone, its complex regulation mechanism involves the interplay between the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and ovaries [3]. Any disruption in this intricate system leads to menstrual irregularities. Stress is considered a significant factor contributing to menstrual disorders, as mental stress affects hormone secretion, thereby disrupting normal menstrual cycles. Even short-term intense stress can have adverse effects on a woman’s menstrual cycle.

Ovarian dysfunction or hormonal imbalances can cause infertility, shoulder and neck stiffness, headaches, and the early onset of menopausal-like symptoms. Prolonged menstruation (lasting more than 8 days) is often associated with hormonal imbalances or uterine pathologies. Hormone imbalance affects related organs such as the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and ovaries, leading to anovulatory cycles or luteal phase defects. Excessive menstrual bleeding, the presence of blood clots, and severe menstrual pain indicate conditions such as uterine fibroids or adenomyosis. Conversely, short menstrual periods (lasting less than 2 days) may be attributed to insufficient hormone secretion or incomplete uterine development. If these issues are ignored, they can lead to infertility.

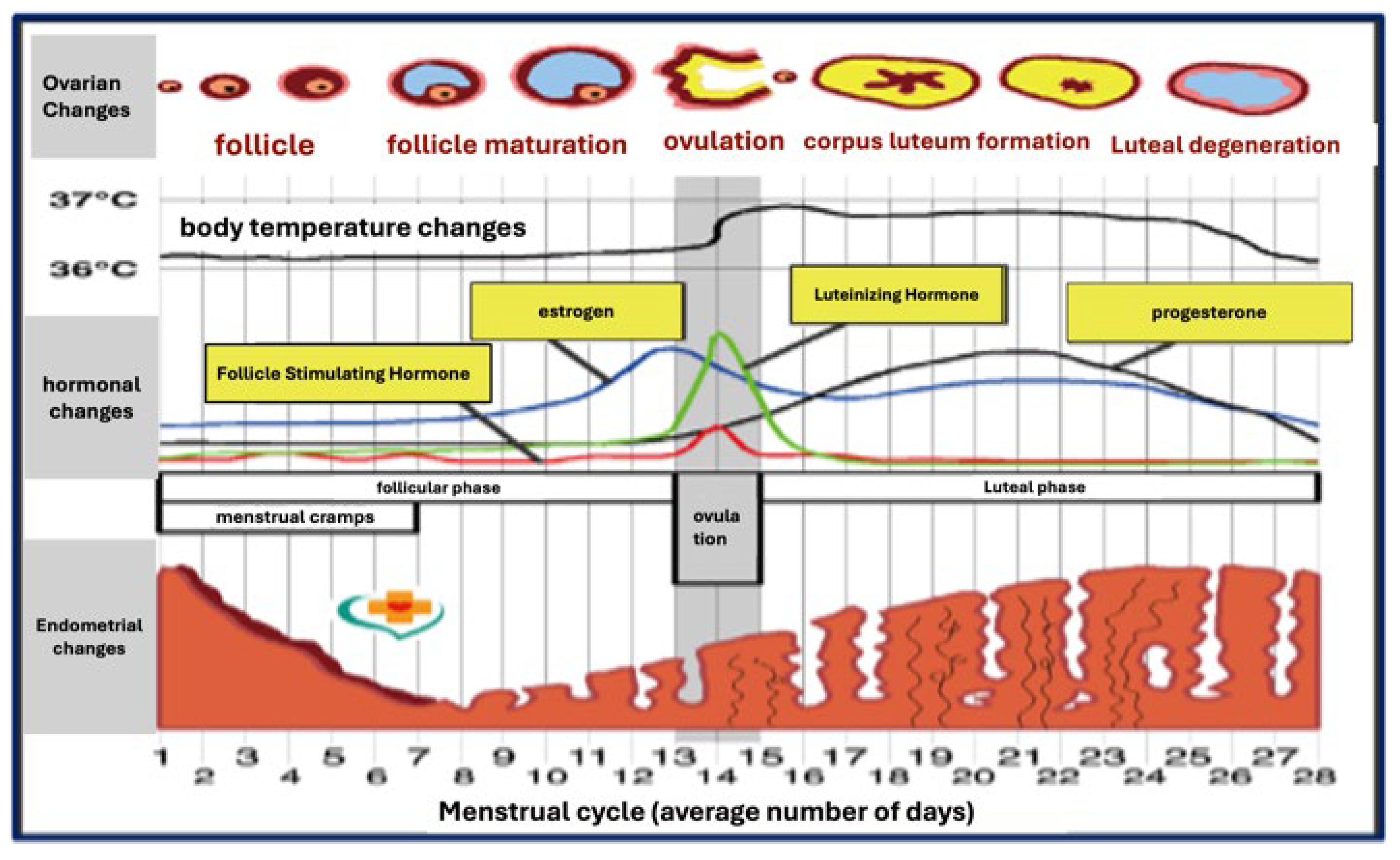

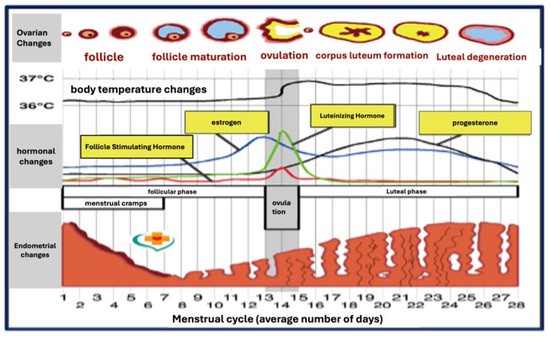

The female menstrual cycle is divided into three phases: the follicular phase, the ovulatory phase, and the luteal phase (Figure 1) [3]. The follicular phase extends from the first day of menstruation to ovulation, and its length is the most variable. The ovulatory phase is between the follicular and luteal phases. Luteinizing hormone (LH) levels peak before ovulation, prompting follicle maturation and ovulation. The luteal phase is relatively fixed, averaging about 14 days, and concludes before the onset of the next menstruation. To fully grasp women’s menstrual cycle health, common ovulation detection methods are described below.

Figure 1.

Female menstrual cycle diagram.

2.2. Common Ovulation Detection Methods

In order to refer to the use of other ovulation detection methods on the market, the following is a list of currently common ovulation detection methods, and the use and comparison of each method are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of seven common ovulation testing methods.

2.2.1. Ovulation Date Calculation Method [4]

This method relies on a regular menstrual cycle. It estimates the ovulation day as 14 days before the first day of the next menstrual period, with the fertile window being five days before and four days after this calculated ovulation day. While simple, this method is only applicable to women with regular menstrual cycles.

2.2.2. Basal Body Temperature (BBT) Measurement [5]

This method involves the daily measurement of body temperature before waking up or engaging in any activity, with the results recorded on a BBT chart. If ovulation occurs, the BBT chart shows a biphasic pattern, with the latter half of the cycle having a temperature of approximately 0.3–0.5 °C higher than the first half. On the day of ovulation, a sudden temperature drop is observed, followed by a sudden increase. If ovulation does not occur, the chart will show a monophasic pattern. However, the BBT method is susceptible to factors such as fever, colds, and insufficient sleep, and therefore has limited reliability.

2.2.3. Cervical Mucus Method [6]

This method involves observing changes in cervical mucus. Before ovulation, the mucus is scant and sticky; during ovulation, it becomes egg-white-like, abundant, and clear. While not requiring any special equipment, this method is affected by vaginal infections, douching, and sexual arousal.

2.2.4. Ovulation Predictor Kits (Opks) Using Urine [7]

This method employs ovulation predictor kits to test urine for luteinizing hormone (LH) concentration. A result where the test line is as dark as or darker than the control line indicates an LH surge, which suggests ovulation will occur within 24–48 h. While convenient, OPKs require repeated testing, and the LH peak might be missed.

2.2.5. Blood Test for Progesterone Levels [8]

This method involves drawing blood to test for the concentration of luteinizing hormone (LH), which provides a more precise indication of the ovulation day than other methods. However, it requires visiting a medical laboratory or hospital, and is time-consuming and inconvenient, as well as being an invasive method. Additionally, blood tests are conducted to assess estradiol (E2) and progesterone levels, assisting in the confirmation of ovulation.

2.2.6. Vaginal Ultrasound for Follicle Monitoring [9]

This is the most direct and accurate method, allowing for the observation of follicle size and maturity. It requires a visit to a hospital and is performed by an experienced professional physician, making it time-consuming and costly.

2.2.7. Saliva Ferning Test [10]

This method observes the formation of ferning patterns in dried saliva before ovulation. This method is simple and economical but requires the use of a microscope, and its accuracy is affected by various factors.

Each aforementioned ovulation detection method has its limitations. The ovulation date calculation method is only appropriate for women with regular cycles, the BBT method is susceptible to interference, the cervical mucus method is subjective, urine-based ovulation test kits may miss the peak, blood tests for progesterone are invasive and time-consuming, vaginal ultrasound is costly, and the saliva ferning test requires expertise.

2.3. Limitations of Existing Menstrual Cycle Management Applications

Recently, numerous menstrual cycle management apps have emerged on the market, capable of recording menstrual periods, calculating cycles, and reminding users of ovulation and menstruation days. These apps even offer calorie logging and sleep-tracking features [11]. For example, Flo, Xiaoyueli, Clue, and PinkBird have shown excellent performance in predicting menstrual periods, with Flo partnering with medical professionals and international health organizations to provide more reliable health information. However, these apps primarily rely on empirical rules for predicting ovulation (i.e., ovulation occurs 14 days before the next menstrual period) and cannot measure users’ physiological data. This limitation leads to imprecise ovulation date estimations.

In contrast, we propose a “non-invasive female ovulation detection method based on heart rate variability”, which extracts heart rate signals non-invasively and then combines HVR analysis with heart rate sensing image processing technology and a self-developed ovulation day detection algorithm to achieve more precise and reliable ovulation date detection.

3. System Architecture

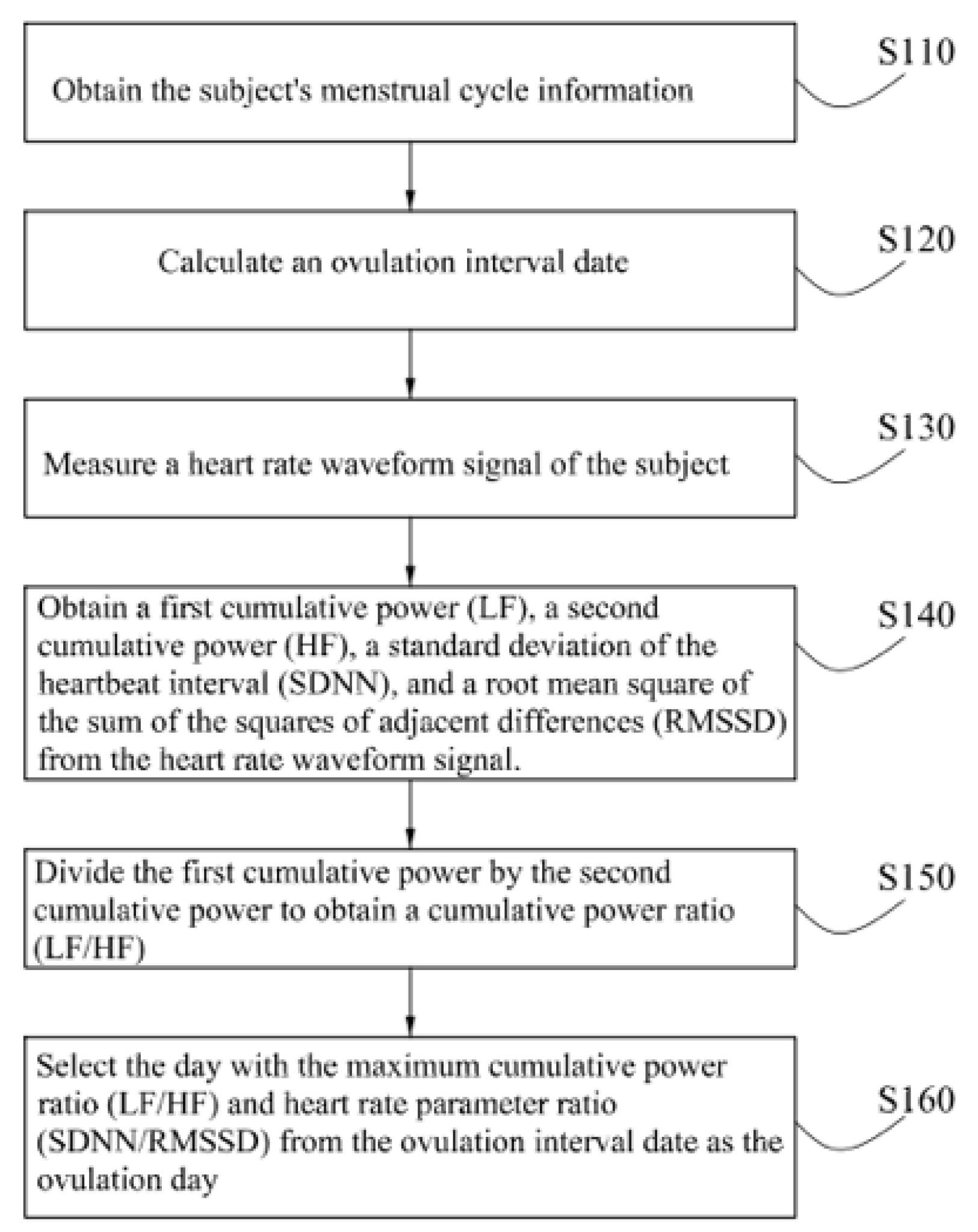

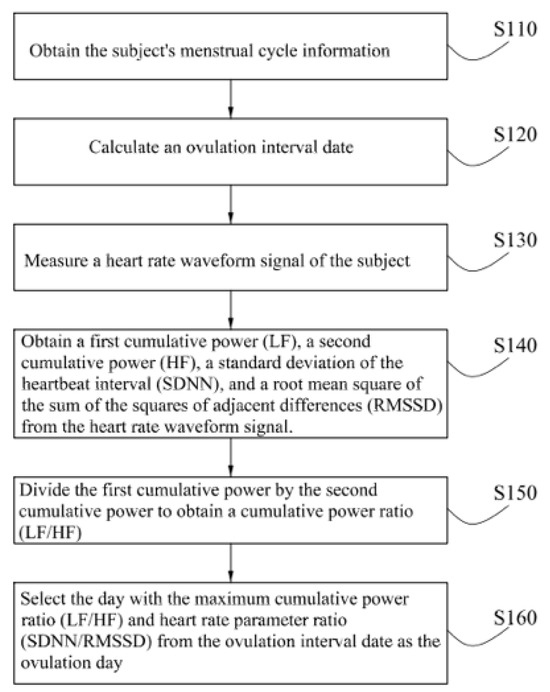

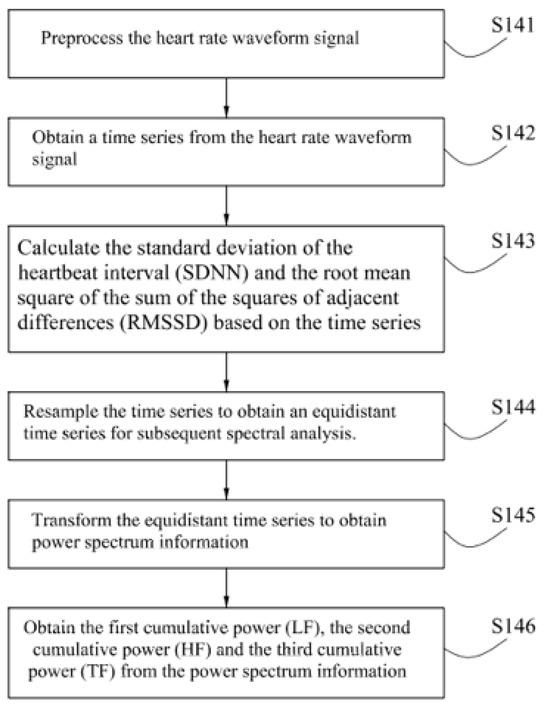

We have developed a system architecture for non-invasively detecting the ovulation day within a woman’s menstrual cycle using HVR analysis. The overarching system is depicted in Figure 2, and the detailed sub-steps for processing the heart rate waveform are shown in Figure 3. The system is structured into several key steps.

Figure 2.

Ovulation detection process during menstrual cycle.

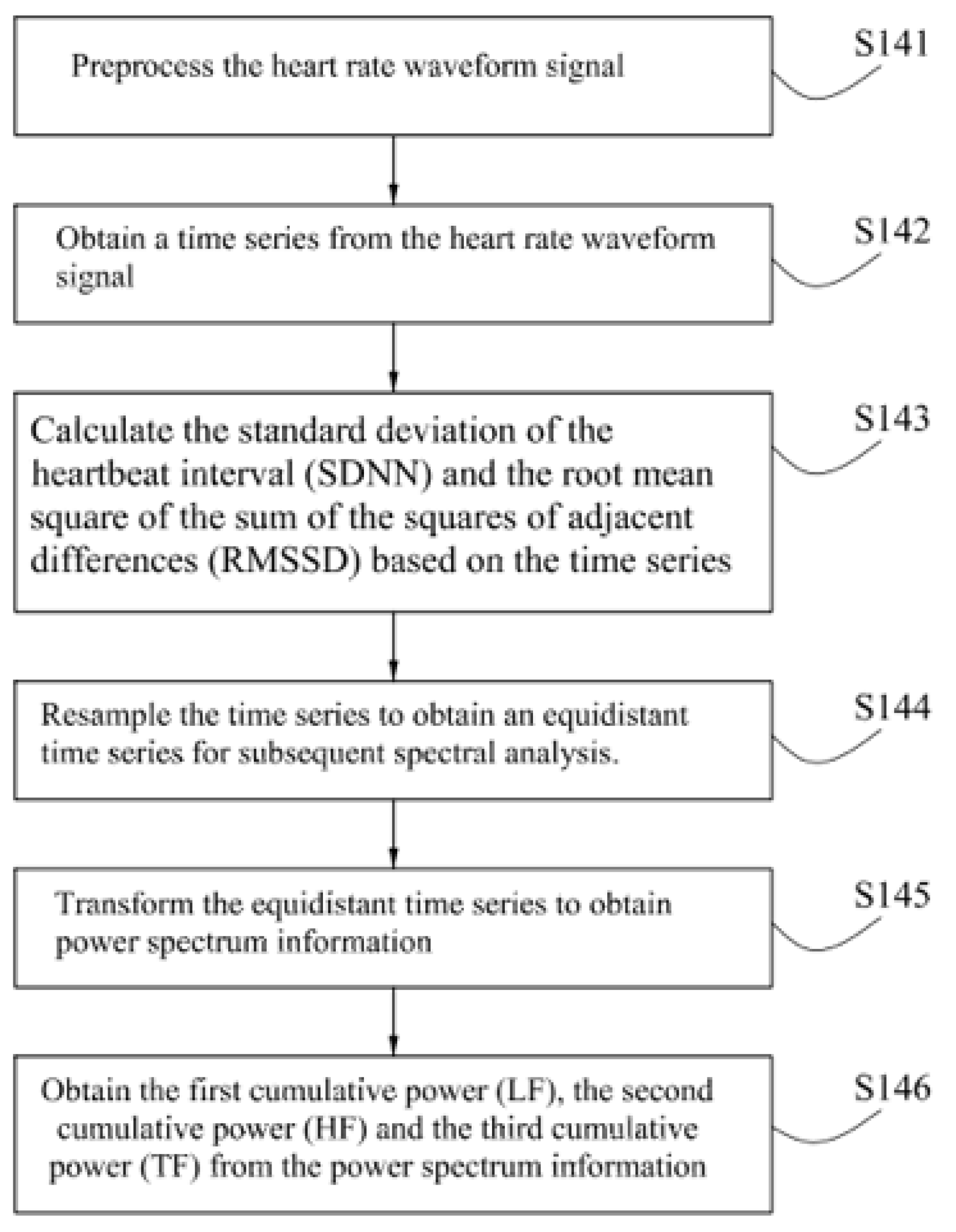

Figure 3.

Calculation of parameters.

3.1. Acquisition of Subject’s Menstrual Cycle Information (S110)

As illustrated in Figure 2, the system initially requires the input of the subject’s menstrual cycle information, including the first day of the cycle, the longest cycle length (L_max), and the shortest cycle length (L_min). If accurate cycle lengths are not available, the system defaults to L_min as 21 days and L_max as 35 days.

3.2. Calculation of Ovulation Interval (S120)

Based on the provided menstrual cycle information, the system calculates the ovulation interval. The start day (OV_start) of the ovulation interval is determined by subtracting 18 days from the shortest cycle length, and the end day (OV_end) is determined by subtracting 11 days from the longest cycle length, calculated using the following equations.

3.3. Measurement of Subject’s Heart Rate Waveform Signal (S130)

The subject’s heart rate waveform signal is acquired using either contact-based measurement methods, such as electrocardiography (ECG) or photoplethysmography (PPG), or non-contact-based methods, such as image signal processing techniques.

3.4. Extraction of Physiological Parameters (S140)

The system then calculates various physiological parameters from the heart rate waveform signal, including the first cumulative power (LF), second cumulative power (HF), the standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN), and the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD). The sampling frequency range for the second cumulative power (HF) is greater than that of the first cumulative power (LF). The sub-processes of this step are illustrated in Figure 2.

- S141: heart rate waveform signal process:

The heart rate waveform signal is preprocessed through steps including amplification, filtering, smoothing, analog-to-digital conversion, and signal drift processing.

- S142: Time series from the heart rate waveform signal:

A time series is obtained from the time intervals between adjacent peaks in the heart rate waveform signal.

- S143: SDNN and RMSSD:

The standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN) and the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) is calculated from the time series using the following time domain analysis.

where RRi represents the time interval between the i-th pair of adjacent R-wave peaks, and N is the total number of adjacent R-wave peak pairs.

- S144: Time series resampling:

The time series is resampled using the Berger algorithm [12] to obtain an equidistant time series suitable for subsequent spectral analysis.

- S145: Equidistant time series transformation:

The equidistant time series is converted to power spectrum information using a Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT).

- S146: Cumulative power (LF, HF, and TF):

The first cumulative power (LF), the second cumulative power (HF), and total power (TF) are obtained from the power spectrum, where the sampling frequency range for LF is 0.04–0.15 Hz, for HF is 0.15–0.4 Hz, and for TF is 0.04–0.4 Hz.

3.5. Calculation of Cumulative Power Ratio and Heart Rate Parameter Ratio (S150)

The cumulative power ratio (LF/HF) is computed by dividing the first cumulative power (LF) by the second cumulative power (HF). The heart rate parameter ratio (SDNN/RMSSD) is computed by dividing the standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN) by the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD).

3.6. Determination of Ovulation Day (S160)

The day within the calculated ovulation interval that exhibits both a maximum cumulative power ratio (LF/HF) and a maximum heart rate parameter ratio (SDNN/RMSSD) is determined as the ovulation day. This selection is validated using time domain, frequency domain, adjacent-day, and screening conditions. Specifically, if on any given day within the “ovulation interval” the heart rate parameter ratio (SDNN/RMSSD) is less than 1.0 or the cumulative power ratio (LF/HF) is less than 1.0, that day is excluded.

4. Results and Discussion

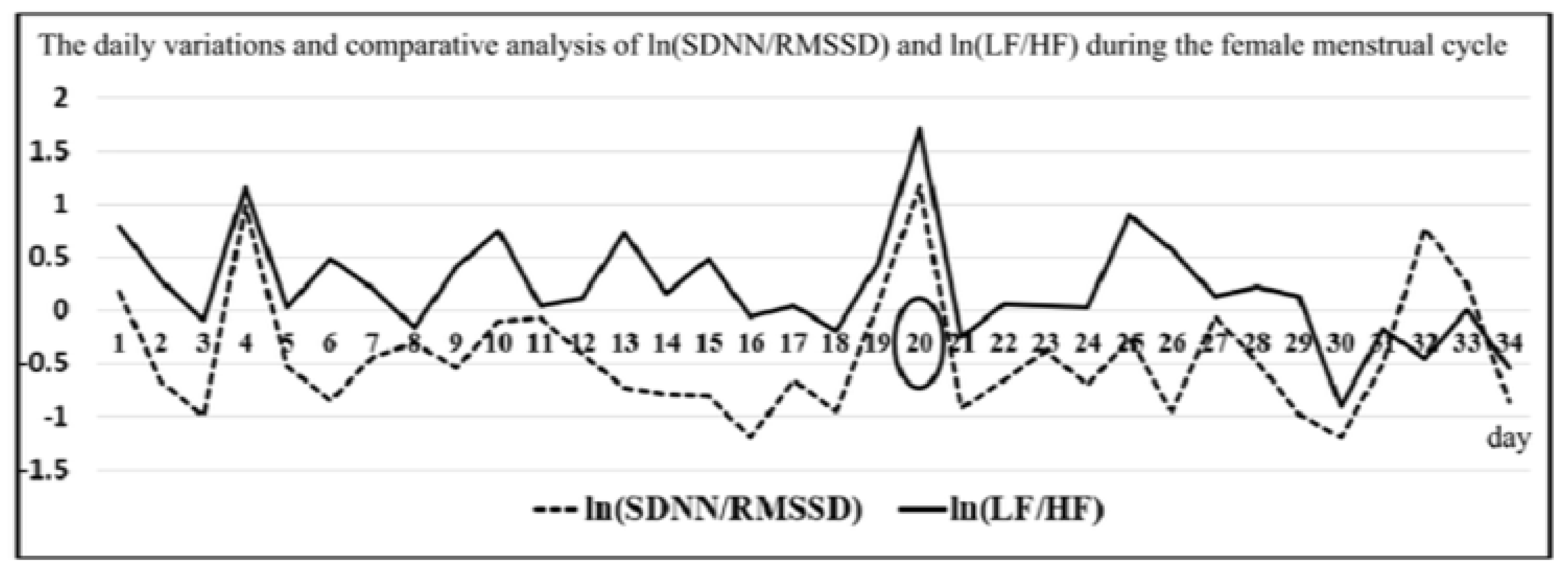

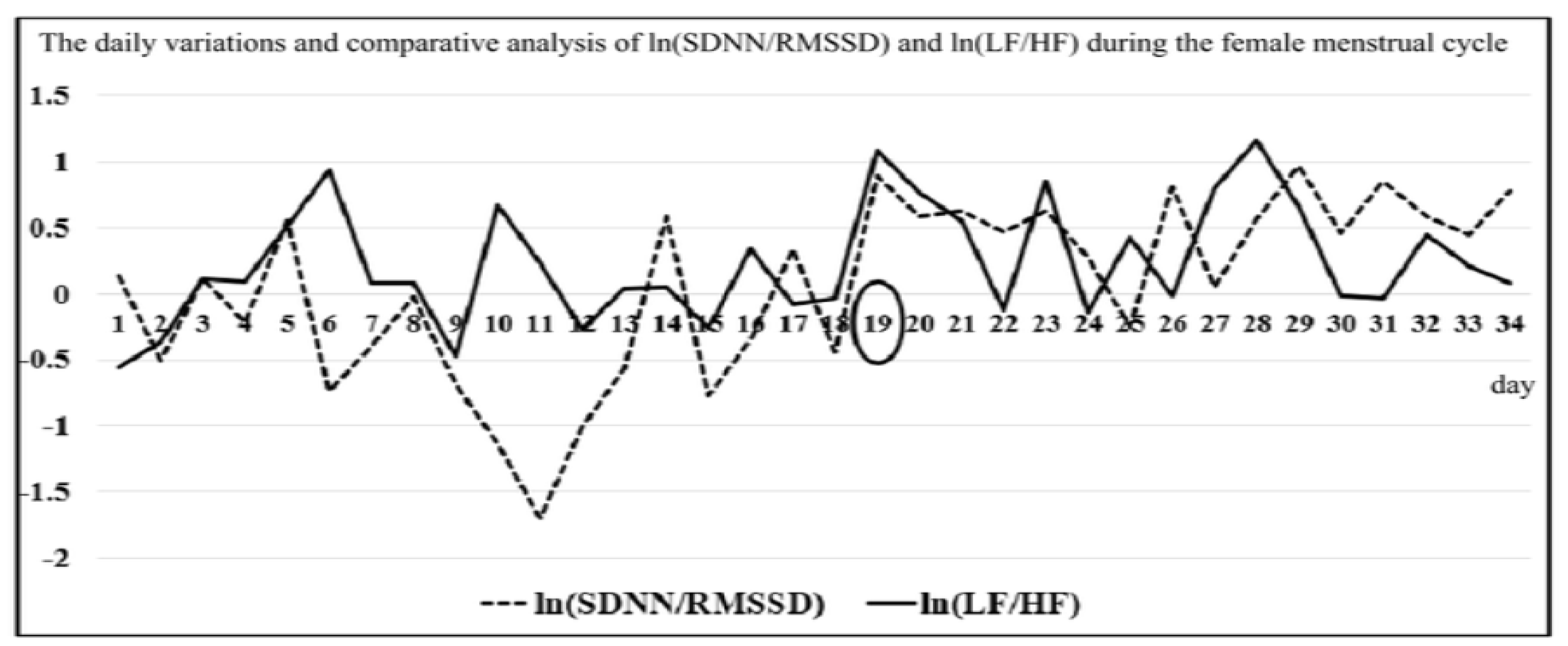

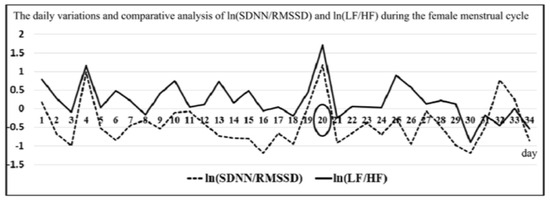

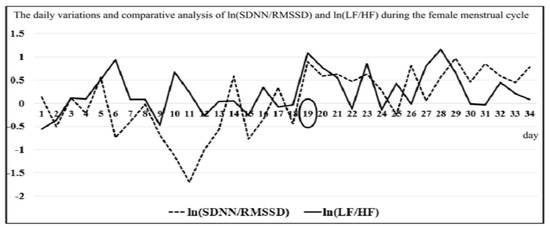

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed female ovulation detection method, practical tests were conducted. Figure 4 (Subject 1) and Figure 5 (Subject 2) present the test results of this experiment. In the experiment, two subjects’ heart rate waveform signals were measured daily after waking up in the morning. Based on the aforementioned methods, HVR indices were calculated, including SDNN, RMSSD, RMSSD percentage, SDNN/RMSSD, LF percentage, HF percentage, and the low-frequency to high-frequency power ratio (LF/HF). These data were recorded daily. Simultaneously, ovulation test strips were used for verification.

Figure 4.

Subject 1’s experiment result.

Figure 5.

Subject 2’s experiment result.

Figure 4 shows the experimental results for Subject 1, illustrating that within the estimated ovulation interval (days 13 to 23 of the menstrual cycle), the maximum values for both the natural logarithm of SDNN/RMSSD (ln(SDNN/RMSSD)) and the natural logarithm of LF/HF (ln(LF/HF)) occurred on day 20, as indicated by the circled mark. The verification result from the ovulation test strip also confirmed that day 20 was the ovulation day. Figure 5 shows the experimental results for Subject 2, which exhibited a similar pattern. Within the estimated ovulation interval (days 13 to 23 of the menstrual cycle), the maximum values for both ln (SDNN/RMSSD) and ln (LF/HF) occurred on day 19, as indicated by the circled mark, and this day was also verified as the ovulation day by the ovulation test strip. This result further validates the reliability of the proposed method.

Although the value of ln(LF/HF) on day 28 and the value of ln(SDNN/RMSSD) on day 29 were higher than those on day 19, these two days were not within the estimated ovulation interval and did not simultaneously satisfy the conditions of both ln(SDNN/RMSSD) and ln(LF/HF) being at their maximum values. Therefore, these days were not misidentified as ovulation days. This demonstrates the developed method’s effectiveness in avoiding misjudgments caused by physiological signal fluctuations during non-ovulatory periods.

The developed female menstrual cycle ovulation detection method utilizes physiological parameters of heart rate waveform signals, such as SDNN, RMSSD, LF, and HF from HVR, detecting the ovulation day by the changes in and ratios of these parameters. The experimental results indicate that this method effectively improves the accuracy of ovulation day detection. Furthermore, its non-invasive nature allows users to easily understand their physiological conditions, demonstrating practicality and convenience.

5. Conclusions

We developed a method for ovulation detection in women based on HVR analysis, using non-invasive methods to acquire heart rate waveform signals. From these signals, various physiological parameters were computed including SDNN, RMSSD, LF, and HF. The method initially calculates the ovulation interval using menstrual cycle information provided by the user. Then, heart rate waveform signals are measured daily within this interval, enabling the extraction of various HRV-related parameters. Key indicators include LF/HF, calculated by LF by HF, and SDNN/RMSSD, calculated by dividing SDNN by RMSSD. The ovulation day is determined by identifying the day within the ovulation interval where both LF/HF and SDNN/RMSSD reach their maximum values. The model demonstrated the effectiveness of this method in detecting the ovulation day while also providing a non-invasive approach that facilitates user understanding of their physiological conditions. This method emphasizes the combination of both time domain and frequency domain indicators of HRV, leveraging HVR parameters as a basis for determining the ovulation day. By implementing screening criteria, this method can effectively avoid misjudgments caused by signal fluctuations on non-ovulatory days.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, Y.-H.L.; data curation, Y.-H.L.; investigation, Y.-H.L.; conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, resources, supervision, project administration, and writing—review and editing, W.-W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank both the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) under the contract number NSTC 113-2637-E-131-008- and the Ming Chi University of Technology (VL001-1500-113) for providing their financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Health Magazine. Dominating, Fascinating, and Controversial Female Hormones. Available online: http://blog.eroach.net/?p=914 (accessed on 24 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Raphael Holistic Clinic. Why Does Menstruation Come with Period Pain? Available online: https://www.raphaelclinic.com.tw/ (accessed on 24 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Hong-Chang Traditional Chinese Medicine Clinic Blog. Reference Website for Gynecological Diseases. Available online: http://tcmcare.blogspot.com/2013/09/gynecological-diseases-a.html (accessed on 24 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Sina Parenting. Six Monitoring Methods to Help Conceive at the Right Time. Available online: https://baby.sina.com.cn/health/mmjk/hzbhy/2021-03-08/doc-ikftpnnz0387148.shtml. (accessed on 24 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Asia University Hospital. How to Measure Basal Body Temperature. Available online: https://www.auh.org.tw/NewsInfo/HealthEducationInfo?docid=1449 (accessed on 24 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Yannigo. Want to Get Pregnant? Cervical Mucus 4-Phase Ovulation Tracking. Available online: https://www.yannigo.com/baike-detail/1/28/662 (accessed on 24 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Wikipedia. Ovulation Test Strip. Available online: https://zh.m.wikipedia.org/zh-tw/排卵試紙 (accessed on 24 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Healing Daily. Pregnancy guide: Eight methods to monitor ovulation and evaluate the accuracy of ovulation blood tests. Available online: https://www.healingdaily.com.tw/articles/懷孕-有沒有排卵懶人包/ (accessed on 24 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Yung Shin Reproductive Center. Gynecological Ultrasound for More Accurate Uterine Examination. Available online: https://www.ivftaiwan.com/share-detail/137/ (accessed on 24 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Taiwan GIST. Development of a Mobile Care System for Predicting Female Ovulation Based on Saliva Image Patterns. Available online: https://taiwan-gist.net/files/past_plan/103/103-12.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- my-best. Top 10 Recommended Period Tracking Apps [2023 update]. Available online: https://tw.my-best.com/115620 (accessed on 24 December 2024). (In Chinese).

- Berger, R.D.; Akselrod, S.; Gordon, D.; Cohen, R.J. An Efficient Algorithm for Spectral Analysis of HVR. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1986, 33, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).