Abstract

Construction accidents cause property damage and harm the environment. The construction industry in the UAE has recorded high fatalities and injuries. However, there has been limited research to prevent accidents on construction sites. Hence, this study aims to uncover the factors causing accidents and prevention measures. All the factors and prevention measures were identified through a literature review and verified in a questionnaire survey. A total of 50 incident causative factors were identified in two groups, and direct and underlying causes and six main preventive measures were determined. The questionnaire survey involved 30 experts who had 10 years of working experience in the UAE construction industry. The experts assessed each of the causative factors and the preventative measures based on a 5-point Likert scale. Reliability was tested on the collected data using Cronbach’s alpha value, and the value was 0.977. The most severe relevant factors of direct causes included violation, taking shortcuts, inadequate leadership/supervision, and human errors. The probability and severity were moderate, and the hazardous activities included unsafe working at height and unsafe lifting. This study shows that workers with experience from 1 to 5 years were engaged in the most accidents. In total, 26 preventive measures were determined. The results benefit the construction industry of the UAE in preventing or avoiding potential accidents at construction sites.

1. Introduction

Buildings and infrastructure development are a part of the construction industry. The UAE has a strong economic foundation, and the construction industry is expanding. According to the United Nations Accounts Database, the UAE was ranked 18th out of 25 countries in the world for construction. It is mandated that all organizations establish a management system for occupational health and safety. Under the mandate, the Abu Dhabi Occupational Health and Safety (OSHAD) Center was established to formulate the requirements, practices, and guidelines for the establishment, implementation, and oversight of occupational health and safety. The most recent version of these guidelines was released in 2017.

The construction industry is one of the most hazardous industries in terms of occupational accidents [1]. There is still a dearth of detail in accident models and the factors for construction accidents. Effective prevention of accidents involves an understanding of significant factors [2]. The factors are interrelated with each other and cannot be isolated. However, there is still a need to realign and re-balance the priorities assigned to factors to significantly improve safety on construction sites [3]. Duryan et al. [4] proved that workplace injuries and fatalities in the UK at construction sites have declined markedly since the occupational health and safety (OHS) management system was introduced [5]. The system summarizes frequent major risks, demanding scientific approaches for investigating fall-from-height incidents and intended preventive measures to enhance safety. Nevertheless, the accidents lack an assessment of the relationship between these factors. Organizational factors and shared values reflect the security perspectives of organization members [6].

Weiy and Jwong (2015) [7] researched safety management, concentrating on safety risk management, environment, behavior, system safety evaluation, and other topics that necessitate a large amount of objective and historical data, including risk analysis, management, and influence. Human beings are affected by safe environments and behavior. The construction industry in the USA implements the concept of designing construction safety as a standard practice to reduce overall project risks [8]. Construction is one of the riskiest jobs in the world. In 2009, the United States’ fatal work-related injury rate for construction workers was three times higher than that of all other workers. The most common cause of injuries was falls from heights.

We carried out a literature review on occupational health and safety to determine related factors. As a result, 53 factors were defined in four categories. Protection equipment for safety, such as guardrails, hard hats, and harnesses, was also researched. Workplace accidents related to scaffolding can be prevented by using the right safety gear and practices, such as locking ladders and having scaffolding inspected by a qualified individual. In the construction industry, trench cave-ins, transportation accidents, and electrocution are the leading causes of fatal injuries. Given that construction works take place in dangerous surroundings, there are many causes of accidents. Accidents increase the costs of construction and negative publicity. Authorities have tightened safety regulations to improve safety on construction sites. However, accidents still occur, which necessitates more research.

Accidents in the construction industry are unanticipated. In construction projects, accident prediction is crucial [9]. In 2014, 4251 workers on private projects suffered fatal injuries, of which 874 were involved in a construction project, according to the United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration. In total, 5% of the occupational fatalities in the US occurred in the construction industry. Additionally, once engineers and designers are aware of the implications of occupational health and safety, key performance metrics for these areas can be improved. In the safety and health performance in the UAE, the design of safety and health measures reduces work-related injuries and related costs and improves work progress and personal protective equipment [10].

According to data from the UAE Labour Office in 2010, 40% of all employees were employed in the construction sector. There are three authorities for construction in the UAE: TRAKHEES, Dubai Municipality (DM), and the Dubai Technology and Media Free Zone Authority (DTMFZA). The authority has its jurisdiction and establishes rules and controls construction. Safety and health measures can be determined by designers, as workers’ health and safety are the contractor’s exclusive responsibility. Designers need to consider safety and health in the design process before the project starts [11]. Al Zarooni, Awad, and Alzaatreh [12] noted that research is necessary to understand how policies have affected industry sectors and work-related incidents. To determine common causes, linkages, and factors of construction accidents, the Labour Inspection Authority investigated 176 significant construction accidents using the construction accident causation (ConAC) method. Worker activities, risk management, immediate supervision, material or equipment usability, local dangers, worker capabilities, and project management were important factors. Causal relationships between these factors were found using a set-theoretic method, risk management, direct supervision, and worker behaviors.

According to Gungor [13], safety signs are crucial for health hazards, fire safety, emergency evacuation, and accident avoidance. These factors are consistently associated with worker behaviors. A correlation between worker behavior, risk management, and immediate supervision was found, highlighting the supervisor’s responsibility for dangerous situations or behaviors and organizing tasks to reduce risks. Planning and risk control at various levels are necessary for risk management and immediate supervision, underscoring the necessity of risk management [14].

The types of accidents are identified using construction accident investigation and reporting systems. However, a sufficient explanation for accident is lacking. Therefore, the theories of accident causes and human errors must be investigated. Due to the unique characteristics of the construction industry, human errors and accident causes must be understood.

The Accident Root Causes Tracing Model (ARCTM), created especially for the construction sector, was used in this study. According to ARCTM, there are three main reasons for accidents: (1) not identifying an unsafe condition that was present before or developed after an activity started; (2) carrying out work even after noticing an unsafe condition; and (3) acting unsafely despite the initial conditions. The ARCTM highlights how critical it is to comprehend unsafe conditions during work, attributing them to four primary causes: (1) mismanagement; (2) worker or colleague misconduct; (3) non-human-related incidents; and (4) an unsafe condition inherent to the original construction site. As a result, the ARCTM offers a comprehensive framework for understanding construction site accidents by acknowledging the possible contributions of both management and labor to the accident process. Preventative action is needed for efficient accident avoidance [15].

The social dynamics at work have an impact on industrial accidents. The sociological explanation is in opposition to safety procedures, which are related to risky behaviors and environmental factors in accidents. Accidents happen at the individual member level as well as at the social level at work. Data from a semi-experimental design were used to assess hypotheses, with variables including shift type (rotating/fixed), shift type (day/night), technology kind, and management styles. Social interactions varied, although the same workers worked in different shifts. The majority of the variations in accident rates between shifts were described by the sociological hypothesis, and statistical analyses indicated that it explains better than other theories. When workers lose orientation, accidents can be avoided by safety management, as described by sociology and by self-control. When making changes to ergonomics, how the workspace’s machinery, plant, and procedures interact with the social dynamics of the workplace must be explained. Social knowledge ought to be incorporated into the ergonomics [16].

Construction-related accidents are a major problem. In Australia, variables and interactions in construction investigations were determined. We examined the contributing variables, preventive measures, and factors in 100 construction accident investigation reports by applying a thematic analysis. We assessed how well they matched up with current theories of accident occurrence. The investigation of construction accidents concentrated on human mistakes to uncover contributing factors and their interactions. The study results highlighted the advantages of using theory-based techniques for accident investigation and analysis as well as significant ramifications [17]. Recently, there has been a noticeable decrease in occupational accidents in the construction industry. Nonetheless, the death toll is still higher than in other industries. Previous research provided analytical models to determine factors of occupational accidents and the causes of accidents. A novel model was constructed by studying various projects and surveying design and site supervision. A thorough analysis of the factors included the state of the economy, the skill of the design team, project and risk management, financial capability, health and safety regulations, and early planning for effective risk prevention [18].

It has been normal practice to avoid construction accidents using the behavior-based approach. Nevertheless, the effects of these treatments did not have advantages. Instead of concentrating on the immediate causes of accidents, systemic variables need to be determined. By examining heat sickness on construction sites, a causal relationship between construction accidents and illnesses was found. In heating sickness, a person is partially the agent and the sufferer. Even though it has the potential to be lethal, the effect affects the afflicted person only and does not spread to others. To determine institutional factors that affect construction accidents in construction, a simplified example of heat sickness was studied. In 36 heat sickness incidents, 216 individual patients from 29 construction sites were interviewed, and site observations were conducted. The study revealed institutional characteristics to support behavioral interventions to prevent heat sickness. The results provided efficient interventions and elements to be improved [19].

A study examining one hundred distinct construction incidents was carried out with focus groups. Qualitative information on the circumstances in each incident and the contributing elements were studied. Interviews with accident participants and their managers or supervisors, site inspections, and evaluations of pertinent records were conducted. For site investigations, stakeholders including designers, manufacturers, and suppliers were consulted. Problems with employees or work groups accounted for 70% of the causes of the accidents. Workplace-related concerns accounted for 49%; equipment flaws accounted for 56% of the accidents; difficulties with material appropriateness and condition accounted for 27% of the accidents; and inadequate risk management for 84%.

A model of an ergonomic system showed how management, design, and cultural elements affected circumstances and behaviors in accidents. For long-term construction safety, it is imperative to address worker issues (unsafe acts/personal factors), workplace issues (unsafe condition factors), equipment/material issues (unsafe condition factors), and management concerns (system factors), which are the categories into which the causal elements of accidents fall. To test a prospective analytic approach of the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) Construction Division, a small sample of fatal construction incidents was studied. This study was conducted as a government inquiry. Out of 211 fatal incidents between 2006 and 2008, 26 occurrences (resulting in 28 fatalities) were included. These accidents were chosen to reflect a variety of accident characteristics. Structured interviews with the investigating inspectors and the inspectorate reports were used to assess the accidents. A systematic categorization was carried out using the Human Issue Analysis and Categorization System (HFACS), covering organizational and task-level issues in addition to mistakes. The results described underlying issues associated with shortcomings in design, procurement and installation, competence assurance, planning and risk assessment, and contracting techniques. By comparing the findings with fifty incidents, the results were verified [20].

Project management involves managing a temporary project team to achieve objectives related to cost, quality, function, and utility throughout all stages of a project’s life cycle by applying fundamental management in planning, organizing, controlling, and leading. Rather than being a fundamental idea, worker safety is frequently seen as an external factor in project management. Planning and environmental restrictions, codes of conduct, labor laws, safety rules, licenses, insurance, and tax laws play a significant role in the construction industry. Since most of these rules and regulations are well stated, it is possible to estimate how they will affect building projects with a fair degree of accuracy. However, it is typical for industrial, safety, tax, and environmental rules to change regularly due to difficulties in law changes and projects. The principal contractor’s major responsibility is to oversee the work of subcontractors.

The construction site is a crucial resource, similar to labor, equipment, materials, and time, and resource allocation is a vital part of construction planning. The construction plan aims to optimize the site by strategically placing facilities in available locations. An effective site layout shortens transportation time, reduces the frequency of material transport, minimizes material re-handling, lowers labor costs, and consequently reduces construction costs. By reasonably assigning construction operation and areas, auxiliary operational areas, and material laydown areas within the site layout plan, conflicts between workers and facilities, between different facilities, between workers and the environment, and between facilities and the environment must be avoided to ultimately enhance the safety level of the construction site.

2. Methodology

A questionnaire was developed for the objectives of this research. The outcome of the literature review was used to develop the questionnaire. It was distributed to construction experts in Abu Dhabi, the UAE, who had more than 5 years’ experience [21]. Four useful recommendations were given in the questionnaire, which consisted of three parts: demography, factors affecting accidents, and prevention measures. In the demography part, the profile of respondents included company category, types of accidents, age, and working experience. Factors of accidents were extracted from the literature review. Preventive measures were also listed based on the results of the literature review (Table 1).

Table 1.

Factors affecting accidents.

3. Results

The measurement scale was used to measure the level of relevancy of the factors, the nature of the incident, the body part affected by the incident, and prevention measures. Table 2 presents the scale used in the survey [22].

Table 2.

Scale in questionnaire.

The questionnaire’s content was validated using the method in Refs. [23,24]. Hill [25] and Isaac and Michael [26] included 10 to 30 respondents in their research. Van Belle [27] included 12 volunteers for their research. In this study, the semi-structured questionnaire survey was carried out for contractors, consultants, and others who had more than 5 years of experience in the UAE. In the survey, the respondents responded online, on the telephone, and via email [26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. A total of 30 respondents were included in the survey, with a return rate of 88% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Respondents and scoring scale.

3.1. Reliability Test

The reliability test results of the 126 items in the questionnaire are displayed in Table 4. Cronbach’s alpha value was calculated for the test. Cronbach’s alpha values were higher than 0.9, indicating legitimacy [33]. The questionnaire had internal consistency, too.

Table 4.

Reliability of questionnaire survey.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

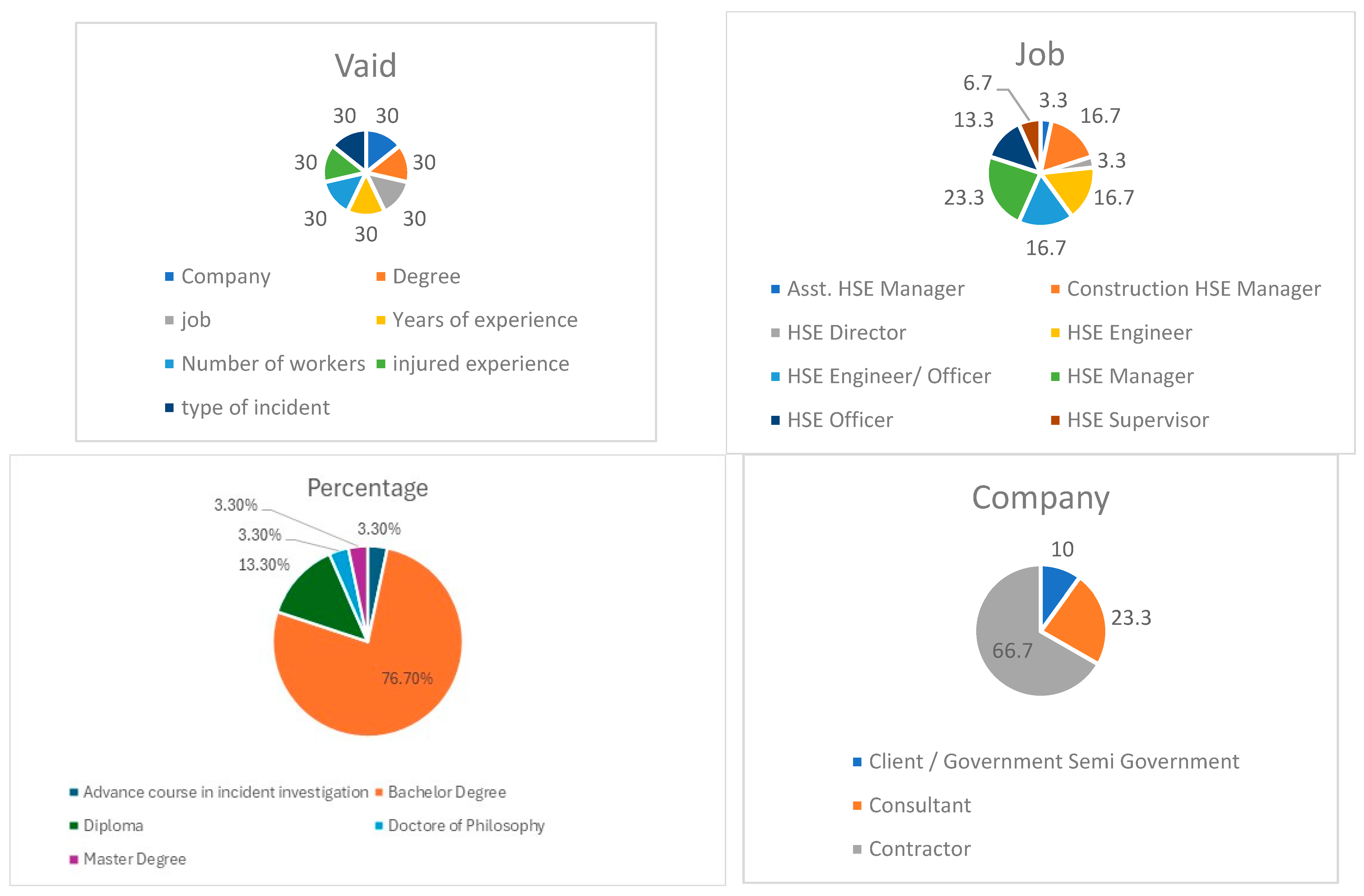

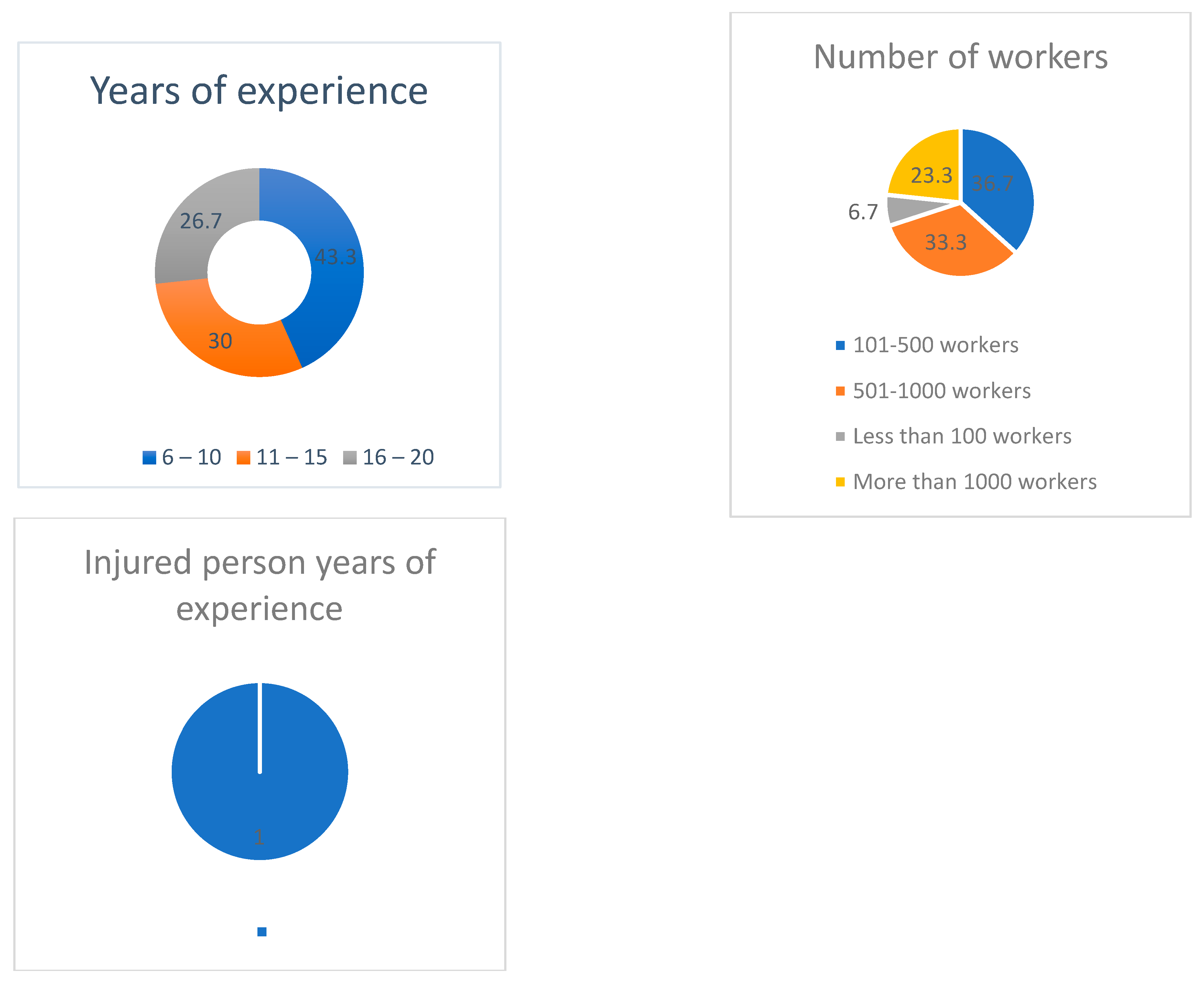

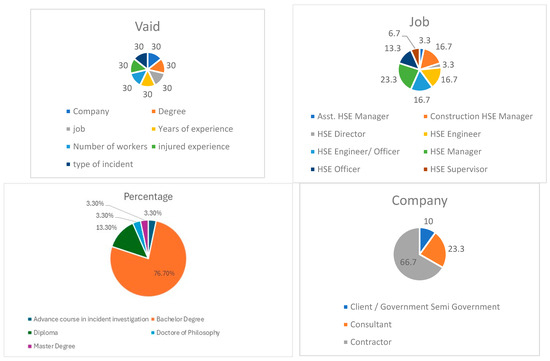

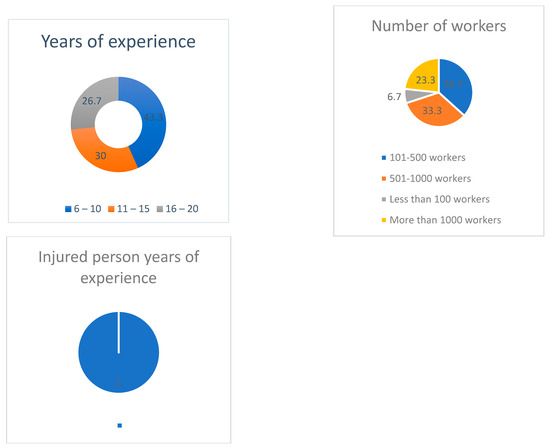

The demography of the respondents is described in Figure 1. The majority (83.3%) held a degree or postgraduate certification, whilst 16.6% had advanced diplomas. Given that the majority of respondents had a decent level of expertise, the questionnaire responses were regarded as reliable. In total, 43.3% of the respondents had experience with occupational safety and health in the construction business, whereas 56.7% had been employed for 11 to 20 years.

Figure 1.

Descriptive statistics of questionnaire survey results.

3.3. Factors and Preventive Measures

Q20 had a p-value of 0.039, and Q57 had 0.031, so they were not statistically significant. Other items were significant statistically. There were 27 slightly relevant factors, 62 moderately relevant factors, and 5 factors that were relevant, while there were no irrelevant or extreme factors, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Factors affecting accidents on construction sites.

The incident preventive measures had no statistically significant difference in the years of working experience, and all of them were scored higher than 4 (extremely relevant), as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Preventive measures and their scores.

A Kruskal–Wallis H Test was conducted for the 30 respondents. Between the three groups of different experiences, there was no statistically significant difference (p-value > 0.05). The mean score was higher than 3 (moderately relevant). Table 7 shows the relevancy of the factors in the expert’s opinions.

Table 7.

Relevancy of factors affecting accidents in expert’s opinions.

In total, 26 methods for incident prevention were identified and were relevant. The methods were grouped into management, personal, task, material, work environment, and personal protective equipment, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Preventive measures.

The hazard relevancy of the accidents in the construction industry is shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Relevancy of factors to accidents.

The risk evaluation and assessment for the construction site showed moderate relevancy (Table 10).

Table 10.

Relevancy of risk evaluation.

The factors affecting the accidents, the nature of the accidents, and related body parts are shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Relevancy of accident nature, mechanism, and related body parts.

4. Conclusions

A total of 92 factors were determined for accidents on construction sites in the UAE in immediate and root causes. The immediate causes were grouped into safe (15 factors) and unsafe conditions (14 factors), while the root causes were grouped into personal factors (7) and system factors (15). Seven causative factors such as direct supervision and local hazards were linked to worker behaviors. There was a substantial correlation between worker behaviors, risk management, and immediate supervision. The results highlight the significance of the supervisor’s management of dangerous conditions/acts and the organization of the jobs to minimize risk. A strong correlation was revealed between worker behaviors and risk management, as well as between risk management and timely monitoring. The significance of risk must be addressed at different levels and by different behaviors in construction projects because risk management and immediate supervision are important in risk control at different levels. Correlations between the causative elements were also observed. To effectively prevent accidents, factors related to requirements, the state of the economy, the skill of the design team, project and risk management, financial capacity, health and safety policy, and early planning must be assessed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, funding acquisition and project administration by First author A.M.M. supervision, by second and third author I.B.A.R. and N.A.B.A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bilir, S.; Gurcanli, G.E. The New Severity Scale of Occupational Accidents for Construction Projects. In Proceedings of the 5th international Project and Construction Management Conference (Conference Paper), Kyrenia, Cyprus, 16–18 November 2018; Civil Engineering Department, Istanbul Technical University: Istanbul, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rafindadi, A.D.; Shafiq, N.; Othman, I.; Ibrahim, A.; Aliyu, M.M.; Mikić, M.; Alarifi, H. Data mining of the essential causes of different types of fatal construction accidents. Heliyon 2023, 9, E13389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, K.; Amrit, S.S.; Benachir, M. Safety Management System (SMS) framework development—Mitigating the critical safety factors affecting Health and Safety performance in construction projects. Saf. Sci. 2021, 143, 105402. [Google Scholar]

- Duryan, M.; Smyth, H.; Roberts, A.; Rowlinson, S.; Sherratt, F. Knowledge transfer for occupational health and safety: Cultivating health and safety learning culture in construction firms. Sci.—Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 139, 105496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.L.; Liu, X.; Peng, C.; Shao, Y. Comprehensive factor analysis and risk quantification study of fall from height accidents. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederico, G.P.M.; Camila, P.D.; Oliveira, C.A.F. Workplace accidents and the probabilities of injuries occurring in the civil construction industry in Brazilian Amazon: A descriptive and inferential analysis. Saf. Sci. 2024, 173, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Weiyan, J.; Wong, K.W.J. Embedding Corporate Social Responsibility into the Construction Process: A Preliminary Study. In ICCREM 2015: Environment and the Sustainable Building, Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Construction and Real Estate Management, Lulea, Sweden, 11–12 August 2015; Wang, Y., Olofsson, T., Shen, G.Q., Bai, Y., Eds.; American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE): Reston, VA, USA, 2015; Volume 11–12, p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Behm, M. Linking construction fatalities to the design for construction safety concept Review. U. S. Saf. Sci. 2005, 43, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asanka, W.A.; Singapore, M.R. Study on the impact of Accidents on construction projects. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Structural Engineering and Construction Management, Kandy, Sri Lanka, 11–13 December 2015; Conference Paper: ICSECM, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hinze, J.; Gambatese, J. Factors Influencing Safety Performance of Specialty Contractors. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2003, 129, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinze, J.; Wiegand, F. Role of Designers in Construction Worker Safety. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 1992, 118, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarooni, A.; Awad, M.; Alzaatreh, A. Confirmatory factor analysis of work-related accidents in UAE. Saf. Sci. 2022, 153, 105813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celal, G. Safety sign comprehension of fiberboard industry employees. Heliyon 2023, 9, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Winge, S.; Albrechtsen, E.; Mostue, B.A. Causal factors and connections in construction Accidents. Saf. Sci. 2018, 112, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, T.S.; Everett, J.G. Identifying Root Causes Of Construction Accidents. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2000, 126, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, T.; Raftery, A.E. Industrial Accidents Are Produced by Social Relations of Work: A Sociological Theory of Industrial Accidents. Appl. Ergon. 1991, 22, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, M.; Goode, N.; Read, G.; Salmon, P. Have we reached the organisational ceiling? a review of applied accident causation models, methods and contributing factors in construction. J. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 2019, 20, 533–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Coutinho, A.; Cardoso, C.V. Correlation of causal factors that influence construction safety performance: A Model. Work 2015, 51, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowlinson, S.; Jia, Y.A. Construction Accidents causality: An institutional analysis of heat illness Accidents on site. Saf. Sci. 2015, 78, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, A.A.B.; Walker, D.C.; Walters, N.D.; Bolt, H.E. Developing the understanding of underlying causes of construction fatal Accidents. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 2020–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedy, P.D. Practical Research: Planning and Design; Prentice-Hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, A.H. Structural Modelling of Factors Causing Cost Overrun in Construction Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Parit Raja, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.-B.; Peng, S.-C. Development of a Customer Satisfaction Evaluation Model for Construction Project Management. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, L.M. Pilot studies. Medsurg Nurs. 2008, 17, 411–412. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, R. What Sample Size Is Enough in Internet Survey Research. Interpers. Comput. Technol. Electron. J. 21st Century 1998, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, S.; Michael, W.B. Handbook in Research and Evaluation: A Collection of Principles, Methods, and Strategies Useful in the Planning, Design, and Evaluation of Studies in Education and the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; EdITS Publishers: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gerald, v.B. Statistical Rules of Thumb; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers, N.; Fox, N.; Hunn, A. Surveys and Questionnaires; The NIHR RDS for the East Midlands/Yorkshire & the Humber Nottingham: Sheffield, UK, 2007; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Szolnoki, G.; Hoffmann, D. Online, face-to-face and telephone surveys—Comparing different sampling methods in wine consumer research. Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechhofer, F.; Paterson, L. Principles of Research Design in the Social Sciences, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frances, R.; Coughlan, M. Interviewing in qualitative research. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2009, 16, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Dibb, S. Using email questionnaires for research: Good practice in tackling non-response. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2006, 14, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, R.A. Measurement Error, Issues and Solutions. In Encyclopedia of Social Measurement; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 665–676. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).