Abstract

Currently, the possibility for the high-value utilization of abandoned oyster shells in the Zhuhai–Macao region of Guangdong Province, China, lacks sufficient attention, leading to resource wastage. Most oyster shells are treated as kitchen waste or directly landfilled, and their potential cultural and material value is not fully realized. To address this issue, this study explores sustainable utilization pathways for local abandoned oyster shells from the dual perspectives of environmental and cultural sustainability. Our research develops a 3D printing material made of oyster shells and designs a series of incense holders inspired by the traditional marine culture of the Zhuhai–Macao area. Within the framework of systematic design, this study focuses on optimizing key aspects such as material regeneration, design transformation, and cultural empowerment, thereby validating the effectiveness of systematic design in material recycling and culturally sustainable innovation. The findings not only provide theoretical and practical support for local ecodesign but also lay a foundation for promoting the synergistic development of environmental and cultural sustainability.

1. Introduction

Currently, the planet faces serious environmental concerns and an expanding scarcity of resources. For this reason, designers are increasingly concerned with reusing material and with design that perpetuates culture locally [1,2]. The Reduce–Reuse–Recycle (3R) principle offers a fundamental strategy for reducing resource waste and easing ecological pressure, and design is gradually shifting toward a system-based approach focused on resource management and cultural empowerment [3,4]. Tang et al. have proposed a “use–display–reuse” packaging framework to extend the lifecycle of cultural products [5]. Rudan has emphasized the value of heritage reuse in promoting cultural tourism [6]. Adenia et al. developed an architecture project integrating 3R principles with public education [7]. Rahmi et al. used 3R training to strengthen residents’ cultural identity and sustainable practices [8]. In recent years, additive manufacturing has shown strong potential in local material reuse due to its small-scale adaptability and material efficiency. It supports distributed design processes based on local sourcing, digital reconstruction, and cultural reinterpretation [9].

The Pearl River Delta region is China’s second largest oyster production area, with output reaching 1141.5 thousand tons in 2018, accounting for 22.2% of the national total [10]. Oyster shells make up more than 75% of oysters’ weight, and with calcium carbonate content as high as 90%, they show potential for recycling [11]. However, abandoned oyster shells from Zhuhai’s restaurant industry are mostly treated as food waste, which wastes resources and may cause environmental problems [12]. Local records show that in the late Qing Dynasty, local boat people and oyster farmers used oyster shells, which symbolize peace and luck, to build houses and make sea offerings.

System design is a method for coordinating multiple elements. It links material and cultural systems and helps support different levels of sustainability goals. Romani et al. have introduced the idea of the “materials designer,” a designer who focuses on finding cultural meaning in materials [13]. Ceccarelli has used the “Neo-local Design” framework to show that cultural sustainability comes from rebuilding local resources in their original context [14]. Pei has further emphasized its re-interpretation in lifestyle and collective memory [15]. The local sourcing—digital reconstruction—cultural reinterpretation pathway uses digital tools to make local resources useful again. Muthu et al. have noted that 3D printing allows people to produce locally while keeping traditional skills and cultural identity [16]. In Chile, Valencia et al. used natural materials like lichen and moss in digital making at their FabLab [17]. Most current methods for using waste in additive manufacturing turn it into polyhydroxyalkanoate filaments for fused deposition modeling printing, but this process is costly and complex. Direct ink writing (DIW) printing works better with natural polysaccharides and inorganic fillers [9]. Perera et al. have found that adding shell powder to natural binders can improve printing stability [18]. Sauerwein et al. and Romario et al. printed with mussel shell powder mixed with sugar water [19,20]. Sauerwein, and Doubrovski tested oyster shells as additives for 3D printing clay [21].

Oyster shells serve as a bridge between cultural and material value, demonstrating significant potential for transformation into cultural products. With the growing emphasis on local material use and low-carbon production, converting local waste into sustainable materials and cultural products has become key to local innovation. Overall, this study aims to (a) explore the upcycling of restaurants’ abandoned oyster shells as bio-based material for 3D printing, (b) investigate the incorporation of local cultural elements from the Zhuhai–Macau region into design processes to ensure repurposed material products are both culturally meaningful and usable, and (c) refine the current system design pathway of local sourcing, digital reconstruction, and cultural reinterpretation to facilitate sustainable material circulation and cultural expression through additive manufacturing processes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overall Methodological Framework

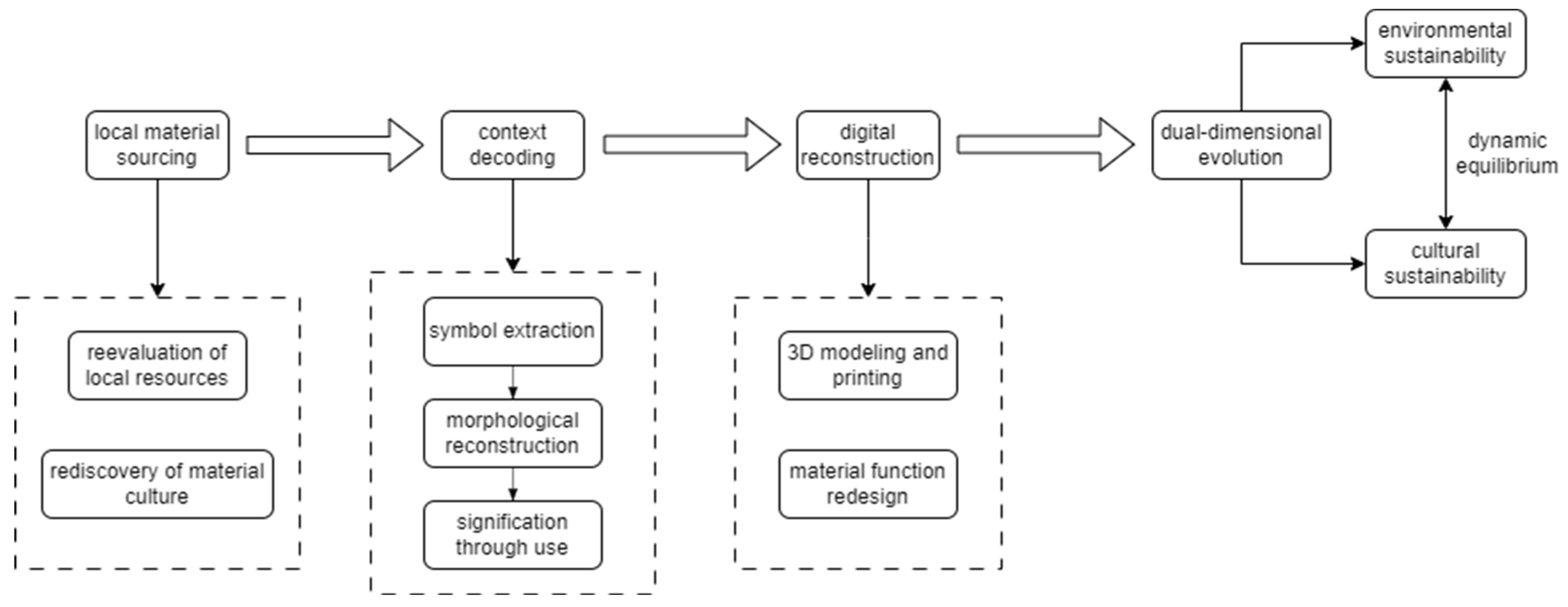

We adopted a system design-oriented multi-method integration approach that combined material experiments, extraction of cultural symbols, and development of prototype design evolution to build up a sustainable redesign closed-loop process based on local sourcing, contextual decoding, digital reconstruction, and dual-dimensional evolution (Figure 1). The overall methodology involves the combination of the multi-disciplinary practice logic of resource-based design research and the system design theoretical framework.

Figure 1.

Closed-loop pathway for sustainable redesign. (Note: Boxes drawn with dashed lines indicate items belonging to the same hierarchy/level).

In this design, local material sourcing extends beyond the physical collection of local materials to encompass the reevaluation of local resources and the rediscovery of material culture, emphasizing the ecological, regional, and overlooked symbolic potential of materials. Context decoding involves researching and interpreting materials to uncover their cultural symbolism through symbol extraction, morphological reconstruction, and signification through use, and then re-encoding cultural symbols into material forms to achieve perceivable, communicable, manufacturable, and sustainable cultural value. Digital reconstruction encompasses not only 3D modeling and printing but also material function redesign, such as DIW printing adaptation. The concept of dual-dimensional evolution in this study refers to both environmental sustainability and cultural sustainability, implying the dynamic equilibrium and developmental needs of their parallel evolution.

In the first step, material experiments are conducted to research the means of converting oyster shells into a printable slurry for DIW, building the material groundwork for the future design of an incense holder. Then, through field studies of Zhuhai–Macau marine cultural beliefs and incense rituals, cultural elements of oyster shell wall textures, Portuguese cobblestone patterns, Macau sacred incense, Mazu worship, and sacrificial rituals involving the sea are abstracted, translated, and re-expressed morphologically. Finally, product prototypes are constructed by virtue of DIW technologies, and cultural recognizability of recreated materials is achieved through the double embedding of material properties and cultural symbols.

2.2. Material Experiment

We used abandoned oyster shells from poultry and seafood restaurants in Zhuhai as the original materials. The entire process, from material collection to producing 3D-printable oyster shell-based materials, will be classified into four stages: recovery and pretreatment, material preparation, printing modification, and post-processing and drying.

At high pressure and low temperature (45 °C, 24 h), abandoned oyster shells were cleaned of organic deposits that carry the risk of decay, roughly crushed, and finely ground. Oyster shell powder of ≤150 μm particle size was collected after sifting through a 100-mesh sieve. A particle size of ≤150 μm, as reported by Licursi & Hernández (2025) [1], increases the stability of composites used in combination with alginate materials, as well as the fluidity and the printability of the slurry.

2.3. Preparation and Formulation of Material

Sodium alginate was dissolved in warm water at 50–60 °C following the addition of potassium sorbate to prevent mold. Due to its slow dispersion but high hydrophilicity, a homogenizer was employed to accelerate dissolution in this research. Glycerol and oyster shell powder were subsequently added to produce a homogeneous paste. The desired concentration of sodium alginate was 5–10% w/v. Glycerol enhances flexibility and extrudability [22]. We ensured printing stability and supported molding strength. The optimal slurry formulation was determined through multiple experimental iterations, as shown below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Printing slurry formulation.

Natural dyes derived from orange-red wood and yellow fragrant flowers—traditionally used in the five-color glutinous rice of Guangxi ethnic minorities as part of their intangible cultural heritage—were adopted for their non-toxicity and cultural significance. The plants were boiled to extract color solutions, which were then used to dissolve sodium alginate, replacing plain water in the preparation of the binder. All other steps remained consistent.

2.4. Printing Process

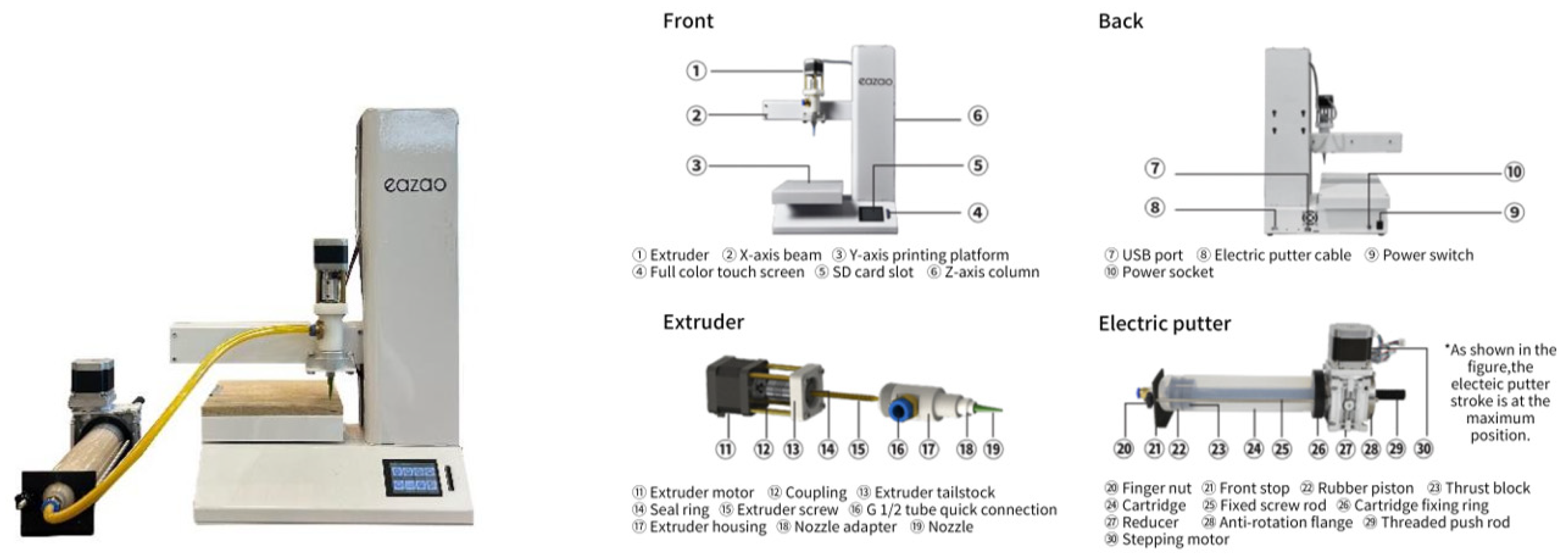

We used the EAZAO DIW-type 3D printer (EAZAO, Qingdao, China). In the absence of heat control to prevent melting, the DIW printer relies on a material’s shear-thinning characteristics and the tendency of the material to gelate quickly. The machine includes an electric pusher, material tube, nozzle, and XYZ triaxial build system. The CAD model design was through Rhino 7, while slicing was performed using Cura 5.6.0. Parameter adjustments were made to suit the material’s properties and to ensure low-speed printing, and the Z-axis was lifted to prevent scraping the nozzle (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Components of EAZAO DIW-type 3D printer.

2.5. Post-Processing and Drying

After printing, the samples along with the substrate were immersed in an 8% CaCl2 solution for 10–15 min, allowing Ca2+ ions to form ionic crosslinks with the carboxyl groups of sodium alginate. This reaction generates a stable calcium alginate gel network, enhancing both structural strength and resistance to deformation [23]. Ca2+ ions diffuse layer by layer from the surface, ensuring uniform crosslinking and improved molding fidelity and surface quality. The drying temperature was set at 40 °C, with humidity controlled at 80–90%. The samples were fully dried after approximately 45 h. Maintaining high humidity helps slow surface hardening, thereby preventing cracks caused by rapid moisture loss. A breathable mesh was used to ensure uniform drying and to prevent deformation by warping.

3. Product Design

We adopted a design method involving local material sourcing, context decoding, digital reconstruction, and dual-dimensional evolution. In the design, a three-color incense holder was developed to explore how local waste can be transformed into a green cultural product.

The Zhuhai–Macau region has a strong tradition of incense worship, with incense holders serving as carriers of folk beliefs and emotions. This research transforms abandoned oyster shells into “wishing objects,” achieving an inversion of material property that demonstrates sustainable cultural design principles. The small scale and simple structure of incense holders match the material characteristics of oyster shells, which, due to shrinkage and brittleness, are not a suitable material for complex components. Incense holders sit at the critical point between controlled experimentation and practical application.

Symbol Extraction and Morphological Reconstruction

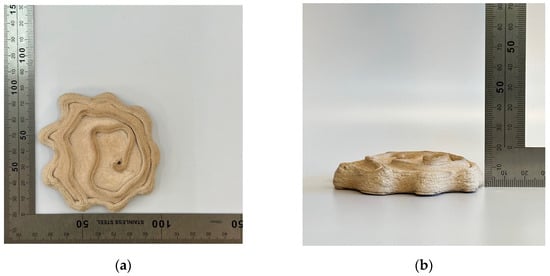

The surface of the incense holder preserves the oyster shell’s natural rough texture, highlighting the material’s inherent qualities (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Through morphological metaphor and surface representation, marine beliefs and everyday experiences from the Zhuhai–Macau region are encoded into the object, establishing the cultural recognizability of the regenerated material.

Figure 3.

Physical incense holder: (a) front view and (b) side view.

Figure 4.

Incense holder color variations: (a) natural color, orange-red wood stain, and yellow floral dye (from left to right) and (b) incense holder in use.

We translated cultural meaning by digitally reconstructing the ecological qualities of oyster shells together with cultural elements from the Zhuhai–Macau region, shaping them into a tangible form that gives the object both cultural recognizability and everyday relevance. The form of the incense holder combines textures from oyster shell houses and Portuguese-style cobblestone paths—the former reflects local sustainable wisdom and the idea of “local material sourcing,” while the latter, as a symbol of Portuguese–Macanese exchange, highlights the cultural hybridity of the Zhuhai–Macau region.

As a local material tied to regional memory and maritime culture, oyster shells are reactivated from a cultural sustainability perspective as a medium that carries both functional and symbolic meaning. By transforming them into an everyday object, a cultural connection is built through use, allowing tradition to continue in a living, evolving form.

4. Material Performance

4.1. Compressive Strength Test

To evaluate the strength and load-bearing capacity of the incense holder (Figure 4), compressive strength was tested using a universal testing machine (Songshu SS-8600-20KN) (Songnu Co., Ltd, Guangzhou, China), in accordance with ASTM C109 [24]. Samples measuring 76 × 98 × 12 mm were placed at the center of the compression plate and loaded at a strain rate of 1.25 mm/min. No visible damage occurred during the test. The maximum load was recorded at 7.2535 mm of deformation, reaching 17,998.715 N.

4.2. Three-Point Bending Test

To examine whether the incense holder is prone to fracture at structurally weak points, a three-point bending test was conducted using a universal testing machine (Songshu SS-8600-20KN), in accordance with ASTM D790 [25]. Samples measuring 76 × 98 × 12 mm were tested with a span length of 40 mm. The loading probe moved downward at a strain rate of 1 mm/min until fracture occurred. The maximum force recorded was 660.990 N.

4.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

To evaluate whether the incense holder undergoes material degradation due to heat from burning incense, thermogravimetric analysis was performed using a Shimadzu TG209F3 analyzer (Shimadzu Corporation, Shanghai, China), in accordance with ASTM E1131 [26]. A 13.14 mg sample was weighed and placed in an alumina crucible. The crucible was then loaded onto the instrument platform and heated from 30 °C to 300 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen flow of 20 mL/min. The results showed a weight loss of 13.57% at 300 °C.

5. Results and Discussion

We showed that the incense holder’s load-bearing capacity, bending performance, and heat resistance all match its function and meet daily use requirements. The experiment tested the oyster shell–sodium alginate composite strategy and led to the development of a bio-based material suitable for DIW printing. The material demonstrated good rheological behavior and formability, meeting initial requirements for both structural stability and environmental compatibility. This provides practical support for resource-driven design. Furthermore, the oyster shell’s association with “ocean–daily life–ritual” imagery further reinforces the product’s symbolic meaning and sense of ceremony.

The design involving local material sourcing, context decoding, digital reconstruction, and dual-dimensional evolution integrates material ecological transformation, structural language in design, and the re-encoding of local culture. It has potential for theory transfer and model expansion, and has proved that circular economy and neo-localism could work together in design practice.

Although this study has achieved preliminary results in material transformation, cultural expression, and the construction of a system pathway, there are still three main limitations to address: (i) In terms of material experimentation, the printing accuracy remains unstable and is noticeably affected by external factors such as weather. Overall material performance is still at an early experimental stage. (ii) The design pathway lacks a user feedback mechanism for validation. (iii) The product prototypes remain relatively uniform, with limited variation in form and structure. Future research should aim to improve material performance and printing processes, including by incorporating user feedback to test the design, and explore a full system linking resource reuse, material design, product development, and cultural communication. The design offers useful insights for circular design in Zhuhai–Macau and other areas.

6. Conclusions

We demonstrated how abandoned oyster shells can be transformed into functional 3D printing materials through a systematic design approach. The oyster shell–sodium alginate composite that was developed proved effective for DIW printing, with the resulting incense holders meeting structural and thermal requirements for everyday use. By integrating local material sources with the extraction of a cultural symbol from the Zhuhai–Macau region, this research moves beyond simple waste recycling to create culturally meaningful products. Our methodology successfully combines material innovation with cultural preservation, showing potential for broader applications in resource-driven design practices that value both environmental and cultural sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-S.L. and L.-Q.K.; methodology, J.-S.L. and L.-Q.K.; software, J.-S.L.; validation, J.-S.L.; formal analysis, J.-S.L.; investigation, J.-S.L.; resources, J.-S.L.; data curation, J.-S.L. and L.-Q.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-S.L. and L.-Q.K.; writing—review and editing, J.-S.L., L.-Q.K., P.-W.H. and C.-Y.W.; visualization, J.-S.L.; supervision, L.-Q.K. and P.-W.H.; project administration, P.-W.H., C.-Y.W. and L.-Q.K.; funding acquisition, P.-W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Science and Technology Development Fund (FDCT; funding number: 0045/2023/ITP2). This article presents the results of a phase of the project titled “The Combination of Two” that was funded by the Major Project of the National Social Science Fund in Arts and Innovation Research on Contemporary Chinese Art Theory (no. 24ZD02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Licursi, D.; Hernández, J.J. Biomass Transformation: Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, E.; Witt, V.; Quijano, J.F.; Dörstelmann, M. Digital Upcyling: Transforming Waste Wood for Circular Construction through Digital Strategies. In Proceedings of the 44th Annual Conference for the Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture (ACADIA), Banff, AB, Canada, 11–16 November 2024; pp. 365–376. [Google Scholar]

- Gruchmann, T. Sustainable engineering change management: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Technologies (ICST 2025), Mysuru, India, 19–20 February 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Salonen, N. Evaluating Circularity Metrics on Industrial Lifting Equipment. Bachelor’s Thesis, Metropolia University of Applied Sciences, Helsinki, Finland, 2025. Available online: https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-202502112628 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Tang, M.; Ge, H.; Sheng, L. Research on the Show-Oriented Sustainable Design of Cultural and Creative Product Packaging Based on the SOR Model. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2025, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudan, E. Circular Economy of Cultural Heritage—Possibility to Create a New Tourism Product through Adaptive Reuse. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenia, I.; Safitri, R.; Pandiangan, M.L. Integrated 3R Waste Processing Facility in Batan Indah as an Educational Waste Tourism Center. In Proceedings of the International Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Factors, Design and Education for Sustainability 2023, Bandung, Indonesia, 14–15 August 2023; p. 012002. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmi, C.; Noor, M.A.; Sukardi, S.; Mulasih, S.; Lesmana, A.S.; Syahreza, A.; Nurdin, N.; Tohiroh, T.; Saefullah, A. Menghidupkan Prinsip 3R: Reuse, Reduce, dan Recycle untuk Masa Depan yang Berkelanjutan Di Kelompok Wanita Tani Garuda 12 Cipayung, Ciputat. J. Community Res. Engagem. 2024, 1, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaali, M.J.; Moosabeiki, V.; Rajaai, S.M.; Zhou, J.; Zadpoor, A.A. Additive Manufacturing of Biomaterials—Design Principles and Their Implementation. Materials 2022, 15, 5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, D.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Pang, D.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, R.; Lin, Y.; Mu, Y.; Zhu, Y. The Oyster Fishery in China: Trend, Concerns and Solutions. Mar. Policy 2021, 129, 104524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Ji, X. Research and Practice of Oyster Shell Building Culture. In HCI International 2022—Late Breaking Papers: Ergonomics and Product Design; Duffy, V.G., Rau, P.-L.P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13522, pp. 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilakala, R.; Thannaree, C.; Shin, E.J.; Thenepalli, T.; Ahn, J.W. Sustainable Solutions for Oyster Shell Waste Recycling in Thailand and the Philippines. Recycling 2019, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, A.; Rognoli, V.; Levi, M. Design, Materials, and Extrusion-Based Additive Manufacturing in Circular Economy Contexts: From Waste to New Products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, N. Neo-Local Design: Viewing “Our Local Environment” as a Potential Resource. Des. J. 2019, 22, 931–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X. Innovation Meets Localism: An Exploratory Study on Design Strategy Towards Cultural Sustainability. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2016, 6, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthu, S.S.; Savalani, M.M. (Eds.) Handbook of Sustainability in Additive Manufacturing. In Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes; Springer: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, A.; Mackenzie, R.; Troncoso, M.; Espinosa, T. Sustainable Design as a Tool for Valorizing Natural Heritage Value Areas in the Southernmost Town in Austral Patagonia, Chile. In Proceedings of the Fab 16 Research Papers Stream, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 9–12 August 2021; pp. 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, P.; Mansouri, S.; Tang, Y. Cellulose-Derivative Based Bigels: Stability and Printability Assessment for Extrusion-Based 3D Printing. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 170, 111642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerwein, M.; Zlopasa, J.; Doubrovski, Z.; Bakker, C.; Balkenende, R. Reprocessable Paste Materials in Circular Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romario, Y.S.; Bhat, C.; Ramezani, M.; Jiang, C.-P. Marine Waste Management of Oyster Shell Waste as Clay Additives for Manufacturing Components. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2025, 12, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerwein, M.; Doubrovski, E.L. Local and Recyclable Materials in Additive Manufacturing: 3D Printing with Mussel Shells. Mater. Today Commun. 2018, 15, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrol, M.D.; Sapuan, S.M.; Zainudin, E.S.; Zuhri, M.Y.M.; Abdul Wahab, N.I. Corn Starch (Zea mays) Biopolymer Plastic Reaction in Combination with Sorbitol and Glycerol. Polymers 2021, 13, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łabowska, M.B.; Skrodzka, M.; Sicińska, H.; Michalak, I.; Detyna, J. Influence of Cross-Linking Conditions on Drying Kinetics of Alginate Hydrogel. Gels 2023, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM C109/C109M-20; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars (Using 2-in. or [50-mm] Cube Specimens). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D790-17; Standard Test Methods for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM E1131-08; Standard Test Method for Compositional Analysis by Thermogravimetry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.