1. Introduction

Food serves as a critical lens for understanding Indian culture, identity, and social structure, reflecting dimensions such as caste, class, religion, ethnicity, and lifestyle. In India’s rapidly evolving socio-economic landscape, food has emerged as a prominent form of cultural expression shaped by globalization and increased consumption. While these changes have expanded dietary choices, they have also contributed to unhealthy eating patterns and a rising prevalence of obesity, emphasizing the importance of effective dietary monitoring and calorie management.

Recent advances in computer vision and machine learning have enabled automated food recognition and calorie estimation through image analysis, offering a practical solution for promoting healthier dietary behaviors [

1,

2]. The increasing availability of food images from social media, mobile applications, and online platforms has facilitated the creation of large-scale datasets, accelerating research in this domain. Automated dish recognition not only supports personal diet tracking and meal planning but also has applications in epidemiological research and the formulation of public health dietary guidelines [

3].

Dietary assessment methods based on visual data can be broadly categorized into image-assisted and image-based approaches. Image-assisted methods complement traditional text-based assessments with manual image analysis, whereas image-based techniques enable fully automated dietary evaluation without human intervention. Although both approaches yield reliable results, image-based systems significantly reduce the workload of nutrition professionals and enhance scalability for real-world applications.

Despite significant progress, food image recognition remains a challenging task due to high intra-class variability, occlusion of food items, irregular shapes, and difficulties in segmentation under complex backgrounds. Additional challenges include accurate volume estimation for liquid foods, non-uniform food density affecting calorie estimation, high computational costs for real-time deployment, and the lack of comprehensive nutritional databases accounting for variations in recipes and cooking methods [

4]. Addressing these challenges is essential for improving the accuracy, reliability, and applicability of food recognition systems in practical health-oriented applications.

The primary objective of this research is to evaluate the effectiveness of deep learning-based food image classification for Indian cuisine using transfer learning techniques. In this study, multiple pre-trained convolutional neural network architectures, including DenseNet, Inception, MobileNet, VGG16, and Xception, are systematically investigated and compared to assess their classification performance. Particular emphasis is placed on the MobileNetV3 architecture due to its computational efficiency and suitability for real-time and resource-constrained environments. Through comparative performance evaluation, this work aims to identify an optimal transfer learning framework for accurate and efficient Indian food classification.

2. Related Work

Reddy, U.K et al. (2022) [

5] developed an automated food classification system using deep learning techniques. SqueezeNet and VGG-16 models were implemented for real-time food image classification in healthcare applications. After dataset augmentation and hyper-parameter tuning, VGG-16 outperformed Squeeze Net, achieving an accuracy of 85.07% due to superior feature extraction.

Nithiyaraj, E.E et al. (2021) [

6] proposed a transfer learning-based food classification framework using AlexNet on the India-Food-21-Categories-Small dataset. Data augmentation was applied to address dataset limitations. The model achieved 96.6% accuracy within five training epochs and supported calorie monitoring and dietary habit analysis.

Survase, A.S et al. (2022) [

7] introduced a CNN-based approach for Indian food classification using multiple pre-trained transfer learning models. The models reduced computational cost and achieved effective classification of food categories, recipes, and automated dietary analysis.

Giramkar, J. et al. (2023) [

8] presented a transfer learning-based CNN framework evaluated on an Indian food dataset with 11 classes. InceptionV3, VGG16, VGG19, and ResNet models were compared, with InceptionV3 achieving the highest accuracy of 87.9% and providing calorie and ingredient information.

Ramesh, A. et al. (2020) [

9] developed a real-time food detection and classification system using an SSD model integrated with CNN architectures. The system achieved an overall accuracy of 97.6%, demonstrating effectiveness for automatic food localization and classification.

Sharma, A. et al. (2023) [

10] proposed a custom CNN incorporating edge and shape features for food image classification. The model achieved 92.89% accuracy on benchmark datasets and improved to 96.27% when combined with InceptionV3 features on a South Indian food dataset.

Zhao, H. et al. (2019) [

11] introduced a few-shot and many-shot fusion learning model for food classification and created the NTU-IndianFood107 dataset. The model achieved a top-1 accuracy of 72% and effectively handled limited and large-sample food categories.

Liu, Y.C. et al. (2022) [

12] proposed an EfficientNet-based framework for multi-dish food recognition with bounding-box detection. The system achieved a mean average precision of up to 92%, enabling real-time recognition and improved dietary reporting.

Patel, J. et al. (2022) [

13] proposed a transfer learning-based Indian food image classification system using the MobileNetV3 architecture, achieving an overall classification accuracy of approximately 90%.

3. Methodology

In the present research, the CNN and transfer learning with DenseNet, Inception, MobileNet, VGG16, and Xception is used. Our Indian food classification system is shown in

Figure 1.

3.1. Indian Food Dataset

The 13_Indian_food dataset [

14] used in this study consists of approximately 3500 images distributed across 13 commonly consumed Indian food categories, with each category containing more than 250 images. This relatively balanced class distribution helps minimize training bias and ensures fair comparative evaluation across different deep learning and transfer learning models. Although Indian cuisine comprises hundreds of regional and traditional dishes, the selected categories represent visually distinctive and frequently consumed foods, making the dataset suitable for benchmarking classification performance under controlled experimental conditions.

It is acknowledged that broader category coverage would further enhance real-world applicability. Future extensions of this work may include expanding the dataset by crawling food images from social media and recipe platforms, crowdsourced data collection through mobile applications, and collaborations with catering services, restaurants, and food delivery platforms to capture real-world variations in lighting, background, and presentation styles.

Preprocessing on Dataset

Upon acquiring the dataset, image preprocessing was performed to enhance image quality and ensure consistency. The research employed a diverse dataset comprising 13 food categories and applied preprocessing techniques such as HSV color space conversion, noise reduction, and edge detection to improve visual clarity and feature representation. Additionally, standard preprocessing operations including normalization, contrast enhancement, and image resizing were carried out. Data augmentation methods such as random rotation, horizontal flipping, cropping, and illumination variation were applied during training to reduce overfitting, increase data diversity, and improve model robustness, particularly for transfer learning models. As part of the rescaling process, pixel values were normalized by dividing each value by 255 to facilitate efficient model training.

3.2. Feature Extraction and Classification

For feature extraction and classification from the images, here we used a Convolutional Network method. We used a CNN model and different transfer learning methods.

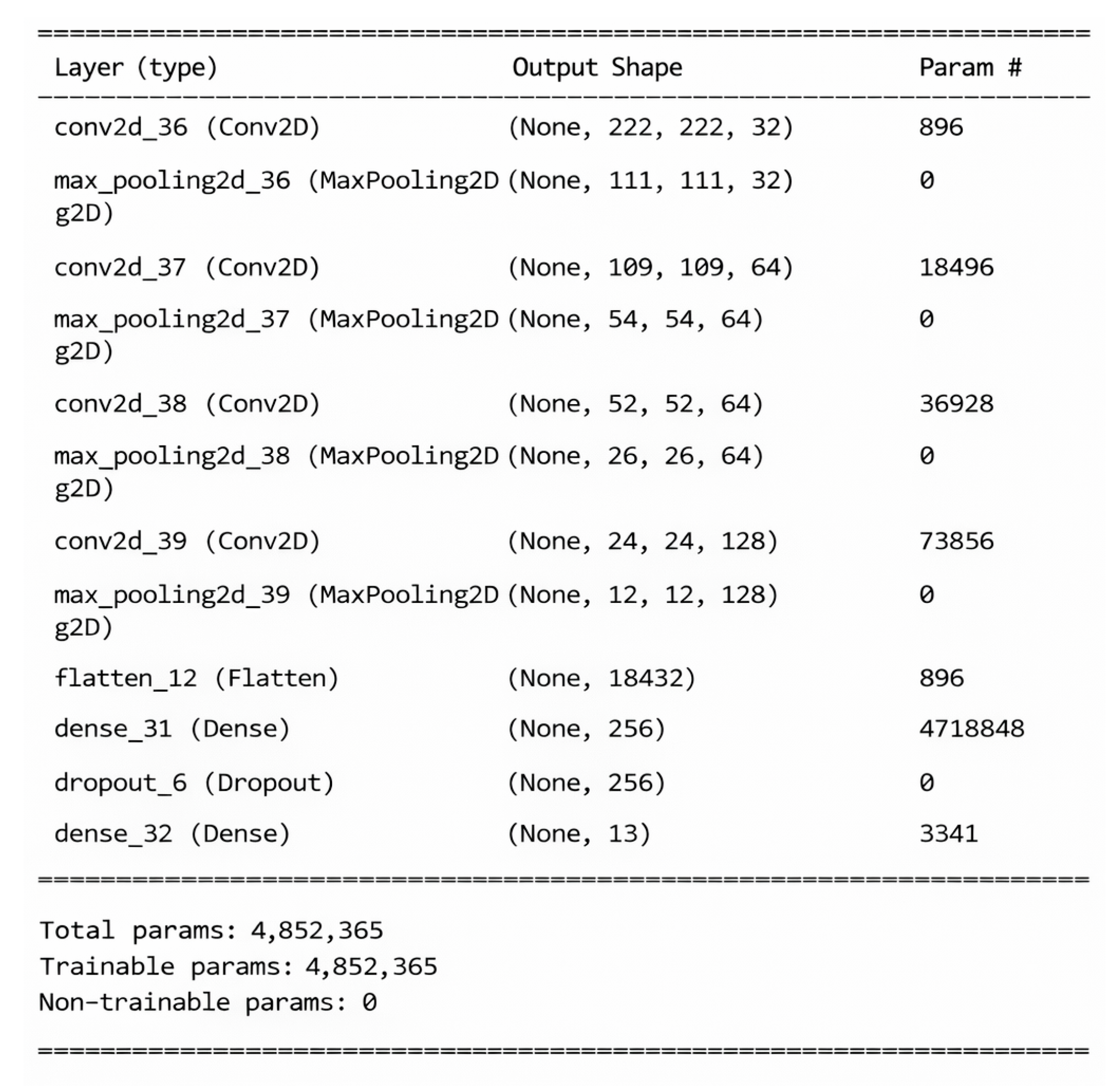

3.2.1. CNN (Self Designed)

The input image is 224 × 224 pixels with 3 channels, and the convolutional layers progressively double the number of filters from 32 to 256, each followed by a 2 × 2 max-pooling layer to reduce dimensionality while preserving key features. The resulting feature maps are flattened and fed into a dense layer with 256 units using ReLU activation, followed by a final dense layer with 13 units and a SoftMax activation function for food image classification. Basic architectural tuning was explored but did not significantly improve performance. Advanced optimizations such as Batch Normalization, alternative activation functions, attention mechanisms, and kernel optimization are identified as future research directions. The model summary is presented in

Figure 2.

3.2.2. Transfer Learning with MobileNetV3

MobileNetV3 [

13] was employed for transfer learning using ImageNet pre-trained weights to enhance food classification performance. The model was used for feature extraction, followed by a dense layer with 1280 units and ReLU activation. Final classification was performed using a dense layer with units equal to the number of food categories (13). The model summary is presented in

Figure 3.

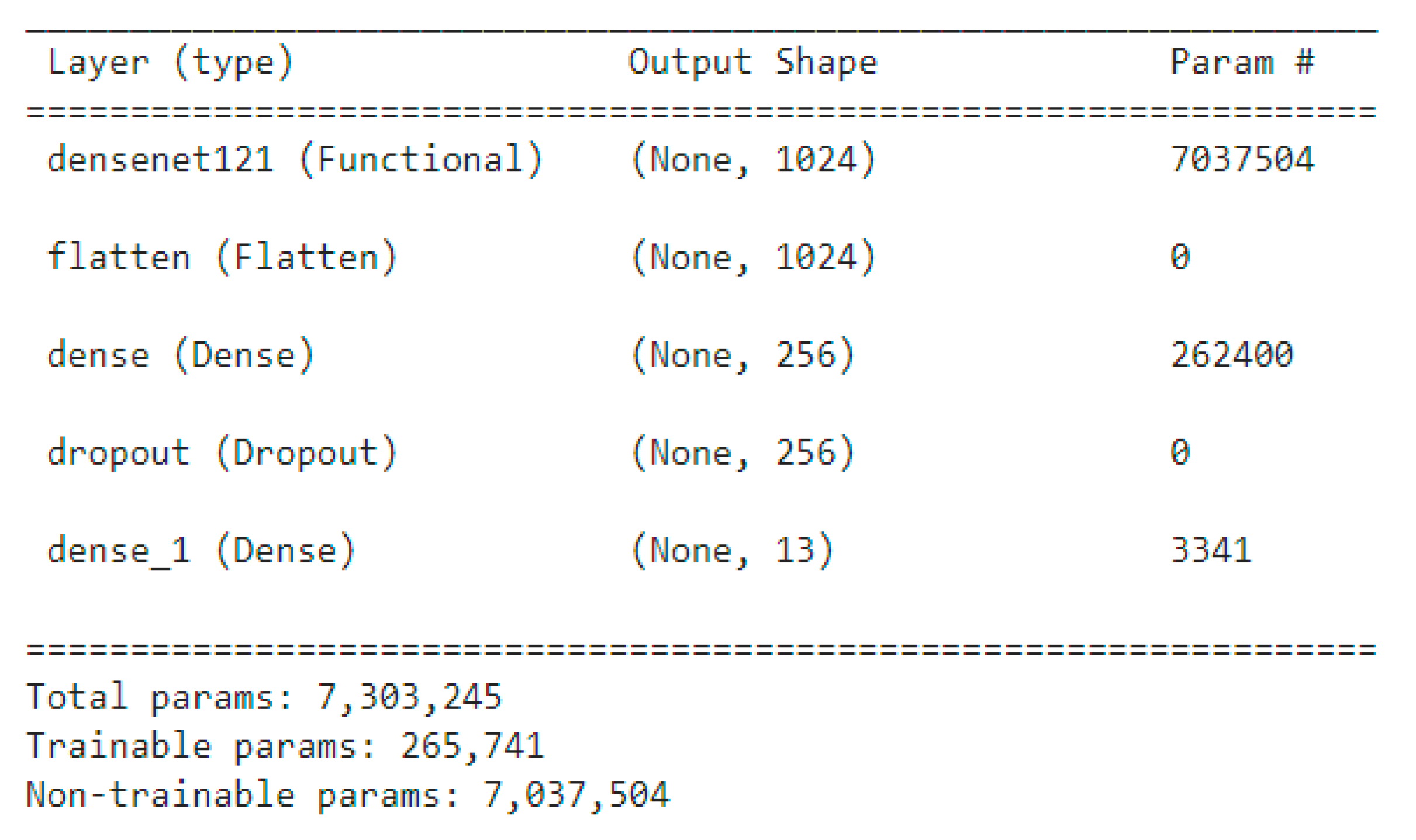

3.2.3. Transfer Learning with DenseNet-121

DenseNet-121 [

15] is a convolutional neural network with densely connected layers that promote feature reuse and mitigate the vanishing gradient problem. Its architecture is well suited for capturing fine-grained details in Indian food images, making it effective for accurate food classification. The model summary is presented in

Figure 4.

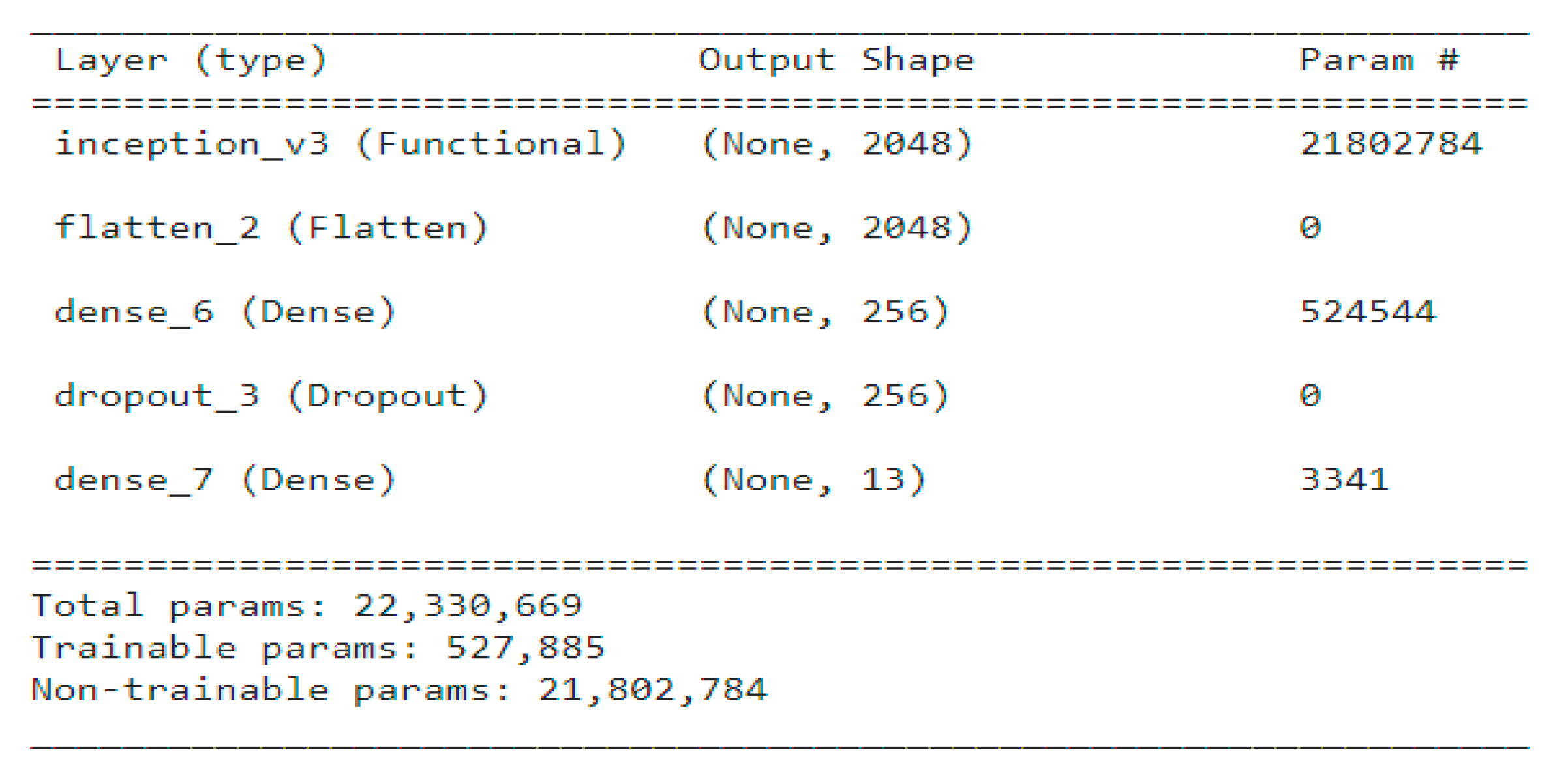

3.2.4. Transfer Learning with Inception

InceptionV3 [

16], also known as GoogleNet, employs multi-scale feature extraction using multiple filter sizes within each layer. This architecture is effective for capturing diverse textures and structural details in Indian food images, enabling improved classification performance. The model summary is presented in

Figure 5.

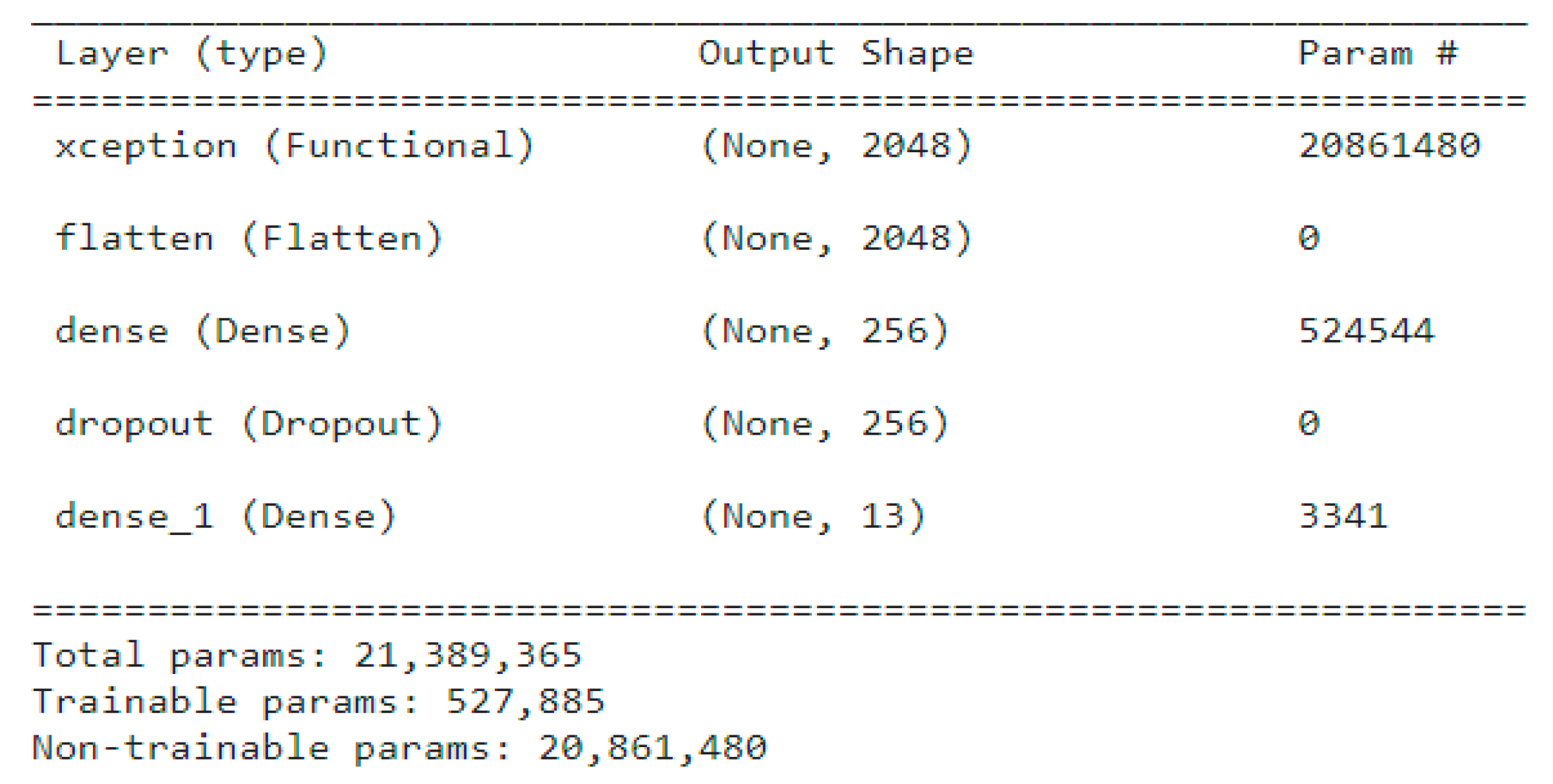

3.2.5. Transfer Learning with Xception

Xception is an advanced variant of the Inception architecture that utilizes depthwise separable convolutions to efficiently learn both local and global features. Its capability to capture complex hierarchical patterns makes it well suited for Indian food classification, where textures and visual variations differ widely across dishes. The model summary is presented in

Figure 6.

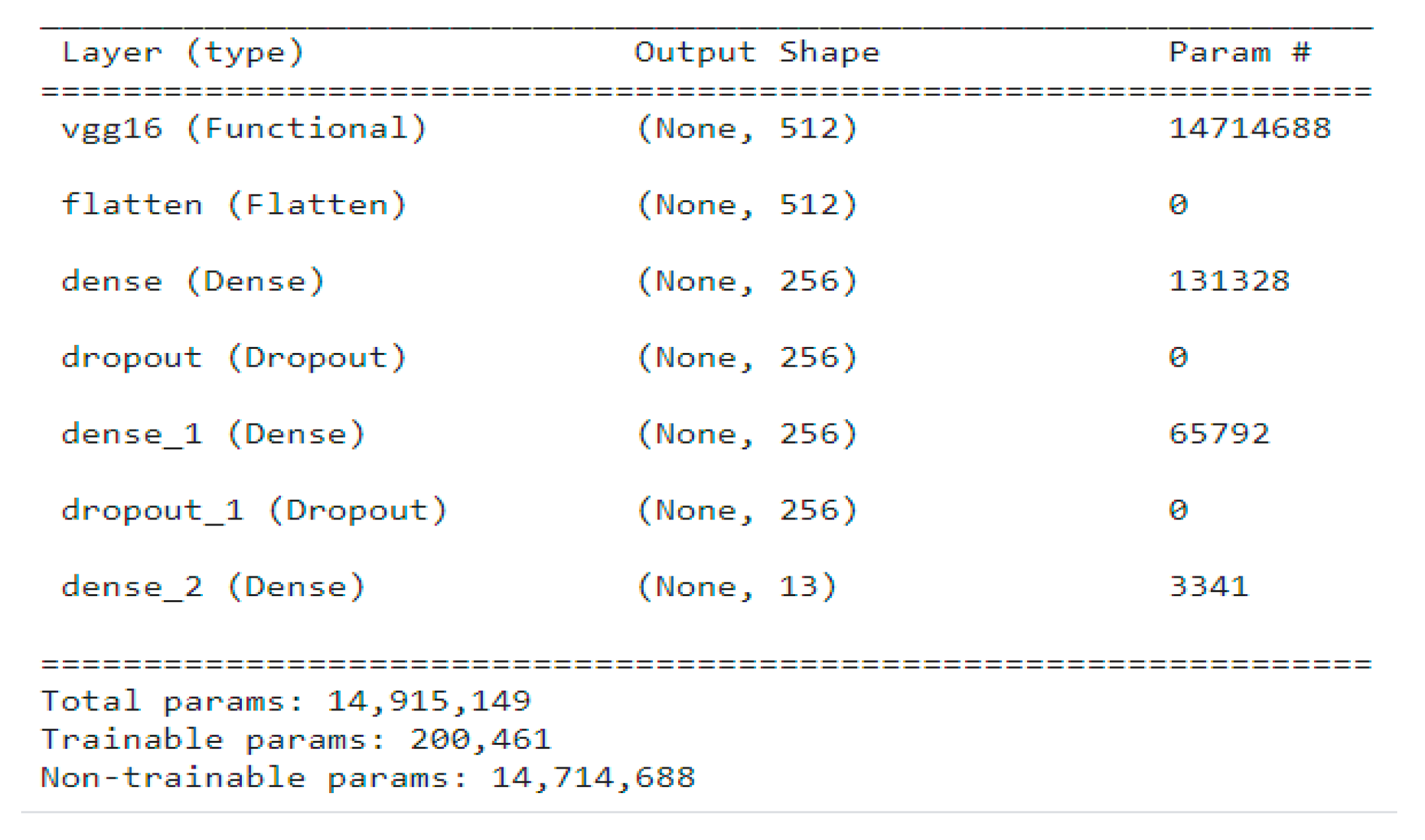

3.2.6. Transfer Learning with VGG

VGG16 [

16] is a deep convolutional neural network recognized for its simple and consistent design. It uses a series of layers with small convolutional filters combined with max-pooling operations. Although it is deeper than some alternative architectures, it remains effective at learning and extracting features from food images. However, it is important to note that VGG16 has a relatively large number of parameters, making it computationally heavier. The model summary is presented in

Figure 7.

3.3. Evaluation

The performance of the classification system is evaluated using standard metrics widely adopted in the scientific community. A confusion matrix is employed to analyze the model’s effectiveness through key parameters, including true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN). Based on these parameters, evaluation metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score are computed.

4. Implementation and Results

The experiments undertaken in this study used Kaggle.com, an online platform specifically built for the purpose of deep learning. The following hyper-parameters were used for the experiments.

Image Size: 224 × 224.

Epoch: 30 for CNN (Self Designed) & 10 for (Transfer Learning Methods).

Optimizer: Adam.

Loss Function: categorical_crossentropy.

Initial learning rate: 0.0001.

Batch size: 32.

The testing accuracy was determined to be 50% for the CNN (Self-Designed) Model. The testing accuracy of different models is shown below in

Table 1.

Misclassifications mainly occur among visually similar dishes with overlapping textures, colors, or presentation styles, often due to complex backgrounds, occlusion, and lighting variations. Transfer learning models show stable performance under moderate viewpoint and illumination changes, while detailed robustness evaluation under severe noise and extreme angles is identified as future work.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the problem of Indian food image classification by comparing a custom-built convolutional neural network (CNN) with several well-known transfer learning models, namely DenseNet, Inception, MobileNet, VGG16, and Xception. The performance of each model was evaluated using standard metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score to ensure a comprehensive comparison. The custom CNN achieved only a moderate performance, with an accuracy of approximately 50%, indicating a limited feature learning capability. In contrast, the transfer learning models demonstrated significantly superior results due to their pre-trained feature representations. DenseNet, Inception, and Xception achieved around 92% across all evaluation metrics, while MobileNet and VGG16 recorded performances in the range of 86–91%. Overall, these findings clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of pre-trained deep learning models, as they provide enhanced feature extraction and improved classification accuracy for diverse Indian food images. Future work will focus on expanding dataset diversity, conducting preprocessing ablation studies, improving custom CNN architectures, and performing detailed robustness evaluations under real-world conditions to further enhance generalization and practical applicability.