The Influence of Corrosion of Steel Reinforcement on the Shear Strength of Existing Structure and 2nd Degree Pre-Earthquake Inspection †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Corrosion of Steel Reinforcement

2.1. The Influence of Corrosion on the Mechanical Properties of Steel Reinforcement

2.2. The Effect of Corrosion on the Shear Strength of RC Members

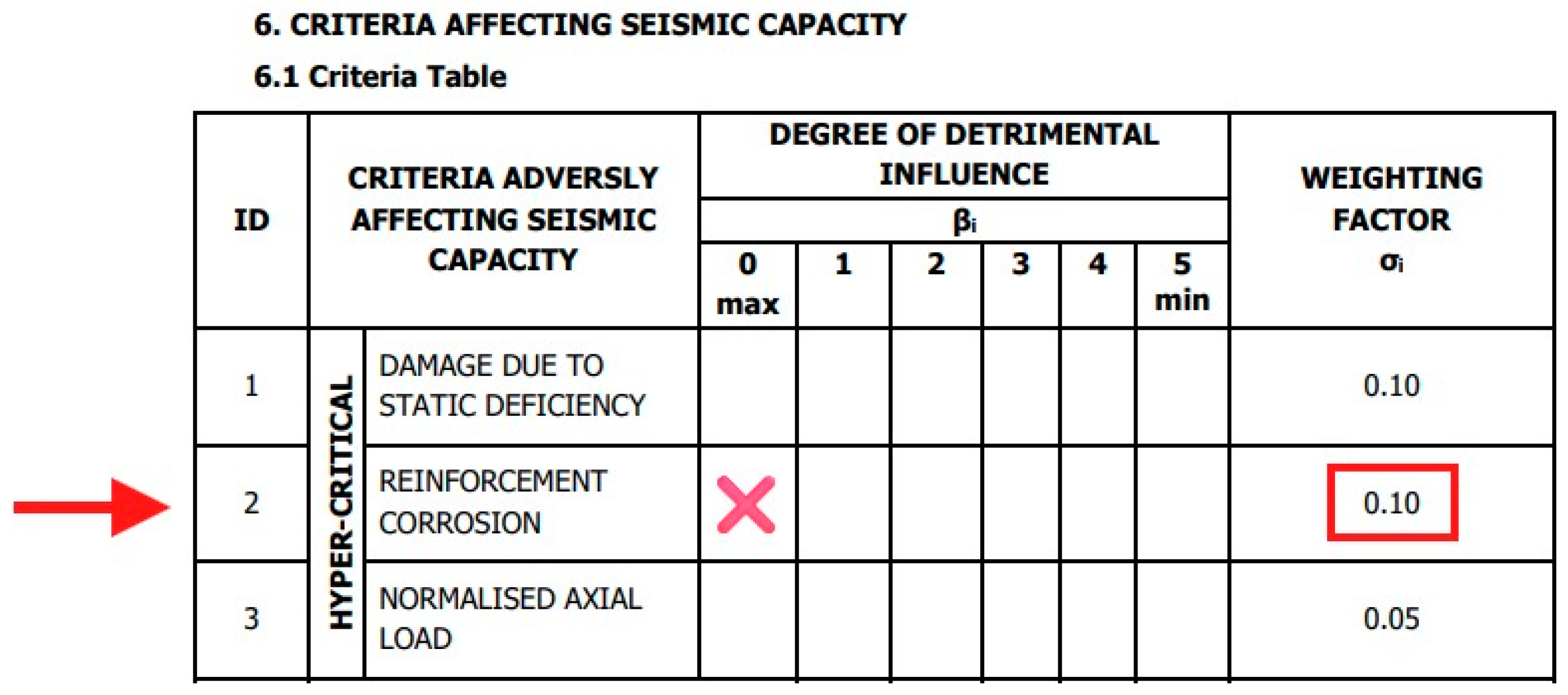

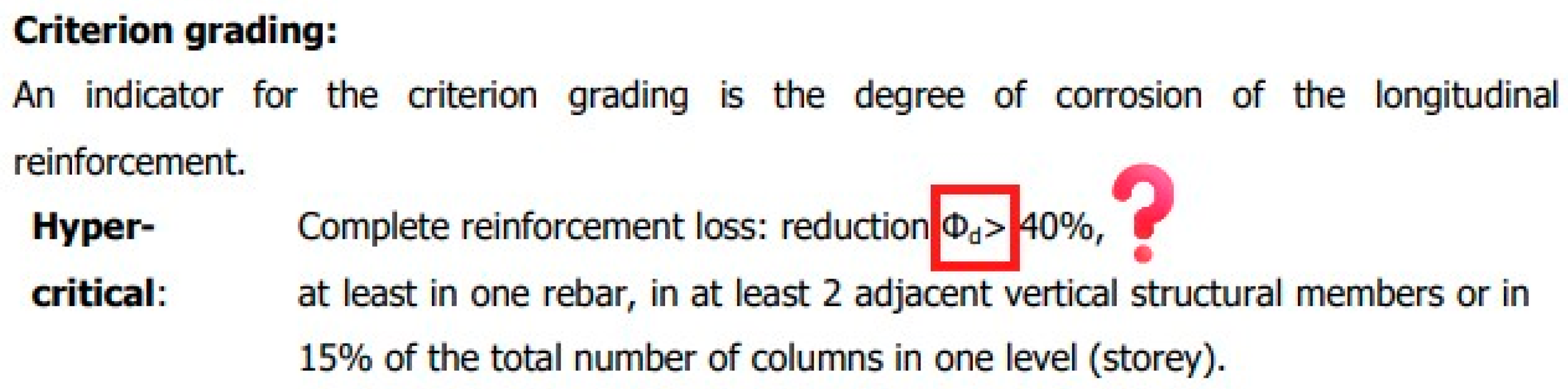

3. Discussion on the Provisions of the 2nd Degree Pre-Earthquake Inspection

4. Conclusions

- Comparing the degradation of the shear strength and the maximum deformation of a structural member, in the presence of corrosion, the guidelines of the 2nd degree Pre-earthquake Inspection overestimate the shear strength, in contrast to several experimental results, which demonstrated its significant degradation due to the corrosive factor.

- Given that the shear strength of a crucial structural element in an earthquake, as in the case of a column, depends significantly on the presence of strong confinement (stirrups), it is worrisome that the 2nd degree Pre-earthquake Inspection does not also address the consequences of corrosion damage on the most vulnerable part of the element, namely, the transverse reinforcement.

- Given that the majority of existing structures are approaching or have already exceeded their useful life, and a pre-seismic check is carried out, considerable emphasis should be placed during the assessment on the corrosive factor so as not to overestimate the structural adequacy of the structures.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Imperatore, S. Mechanical properties decay of corroded reinforcement in concrete—An overview. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2022, 3, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprili, S.; Moersch, J.; Salvatore, W. Mechanical performance vs. corrosion damage indicators for corroded steel reinforcing bars. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 2015, 739625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbari, K.; George, D.-W.A.; Kennedy, C. The Effect of Corrosion on the Mechanical Properties (Diameter, Cross-Sectional Area, Weight) of the Reinforcing Steel. Middle East Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2024, 4, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earthquake Planning; Protection Organization-EPPO. 2nd Degree Pre-Earthquake Inspection of Reinforced Concrete Buildings, 1st ed.; Earthquake Planning & Protection Organization-EPPO: Athens, Greece, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Earthquake Planning and Protection Organization (OASP). Code of Structural Interventions (KAN.EΠE.), 3rd ed.; Earthquake Planning and Protection Organization (OASP): Athens, Greece, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Imperatore, S.; Rinaldi, Z.; Drago, C. Degradation relationships for the mechanical properties of corroded steel rebars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 148, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Joukhadar, N.; Tsiotsias, K.; Pantazopoulou, S. Consideration of the state of corrosion in seismic assessment of columns. Int. J. Struct. Integr. 2020, 11, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andisheh, K.; Scott, A.; Palermo, A.; Clucas, D. Influence of chloride corrosion on the effective mechanical properties of steel reinforcement. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2019, 15, 1036–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, C.A.; Drakakaki, A.; Basdeki, M. Seismic assessment of RC column under seismic loads. Int. J. Struct. Integr. 2019, 10, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basdeki, M.; Koulouris, K.; Apostolopoulos, C. Effect of Corrosion on the Hysteretic Behavior of Steel Reinforcing Bars and Corroded RC Columns. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulouris, K.; Apostolopoulos, C. An experimental study on effects of corrosion and stirrups on bond behavior of reinforced concrete. Metals 2020, 10, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, S.; Imperatore, S.; Rinaldi, Z. Influence of corrosion on the bond strength of steel rebars in concrete. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Li, H.; Ba, X.; Guan, X.; Li, H. Experimental investigation on the cyclic performance of reinforced concrete piers with chloride-induced corrosion in marine environment. Eng. Struct. 2015, 105, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Che, Y.; Gong, J. Behavior of corrosion damaged circular reinforced concrete columns under cyclic loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 29, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-Y.; Song, X.-B.; Jia, H.-X.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.-L. Experimental research on hysteretic behaviors of corroded reinforced concrete columns with different maximum amounts of corrosion of rebar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 121, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEB-FIP. FIB Model Code 2010: Structural Concrete; Ernst and Sohn: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 152–189. [Google Scholar]

- Meda, A.; Mostosi, S.; Rinaldi, Z.; Riva, P. Experimental evaluation of the corrosion influence on the cyclic behaviour of RC columns. Eng. Struct. 2014, 76, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Zheng, S.; Zheng, H.; Li, Y.; Dong, J. Seismic behavior and damage evolution of corroded RC columns designed for bending failure in an artificial climate. Structures 2022, 38, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, K.; Zhu, B.; Liu, Y.; Ni, K. Deterioration of Mechanical Properties of Axial Compression Concrete Columns with Corroded Stirrups Coupling on Load and Chloride. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.-Q.; Feng, P.; Ozbolt, J.; Ye, H. Effects of the corrosion of main bar and stirrups on the bond behavior of reinforcing steel bar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 225, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Basdeki, M.; Koulouris, K.; Apostolopoulos, C. The Influence of Corrosion of Steel Reinforcement on the Shear Strength of Existing Structure and 2nd Degree Pre-Earthquake Inspection. Eng. Proc. 2025, 119, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119053

Basdeki M, Koulouris K, Apostolopoulos C. The Influence of Corrosion of Steel Reinforcement on the Shear Strength of Existing Structure and 2nd Degree Pre-Earthquake Inspection. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 119(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119053

Chicago/Turabian StyleBasdeki, Maria, Konstantinos Koulouris, and Charis Apostolopoulos. 2025. "The Influence of Corrosion of Steel Reinforcement on the Shear Strength of Existing Structure and 2nd Degree Pre-Earthquake Inspection" Engineering Proceedings 119, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119053

APA StyleBasdeki, M., Koulouris, K., & Apostolopoulos, C. (2025). The Influence of Corrosion of Steel Reinforcement on the Shear Strength of Existing Structure and 2nd Degree Pre-Earthquake Inspection. Engineering Proceedings, 119(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025119053