1. Introduction

The operation of long freight trains is accompanied by various problems. A significant one is related to the high longitudinal forces in the couplers. It is known that the highest forces in the longitudinal direction are generated during braking [

1,

2,

3]. Their magnitude depends on many factors related to the characteristics of the rolling stock, the braking system, and its operation. Regarding the efficiency of the braking system, there are two factors that have the greatest impact:

- -

The speed of propagation of the braking wave;

- -

The working mode of the distributor valve.

Due to the delay of the braking signal along the length of the train because of the scattering of the braking wave [

4] in order not to have high in-train forces, the filling times of the brake cylinder need to take several seconds. The filling time of the brake cylinder is called non-stationary period and is formed by the distributor valve. The operating positions of the distributor valve are G, P, and R and are characterized by filling and releasing times, respectively [

5,

6,

7,

8]:

- -

Position G—18 ÷ 30 s filling time and 45 ÷ 60 s releasing time;

- -

Position P—3 ÷ 5 s (3 ÷ 6 s for load-dependent braking) and 15 ÷ 20 s (15 ÷ 25 s for freight wagons with a gross weight of over 70 t, respectively);

- -

Position R—the same as P but with different pressure, depending on the speed of the train.

The differences in the filling times of the distributor valve and the different lengths and masses of the rolling stock are responsible for the longitudinal forces occurring during train operation. The greater the propagation speed of the braking wave, the lower the in-train forces. This means that the highest values of longitudinal forces are generated during service braking due to the lower propagation speed of the braking wave [

9]. During emergency braking, the propagation speed of the braking wave is equal to 275 m/s, and the full-service braking propagation speed is 225 m/s [

9].

Also, longitudinal forces have a significant impact on the strength and durability of the rolling stock and its components [

10], and in some cases, it can cause derailment [

11]. In Ref. [

12], accelerations for fatigue testing of the material in the three spatial directions are specified for all rolling stock, but in Ref. [

13], the main attention (for freight wagons) is on the y and z directions. This consideration does not account for the role of longitudinal loads (x-direction), which are particularly evident in braking conditions. In Ref. [

14], longitudinal forces are also included in the design of bogies, both in the static and fatigue tests, and in Ref. [

15], the impact of the braking process is taken into account.

Numerous studies including [

10] show that the fatigue of materials and assemblies in wagon structures can be affected by neglected longitudinal loads. In practice, a number of cases of damage to the traction-deflection system have been documented—for example, broken hooks, suspensions, and connecting elements [

16,

17,

18,

19]. These damages are often due to accumulated dynamic forces that are not fully taken into account when dimensioning structures using current standards.

By optimizing and precisely controlling the braking system, it is possible to significantly reduce longitudinal forces, which would not only improve braking efficiency and reduce loads in the couplers but would also increase the reliability of the entire railway fleet [

10,

15]. This would avoid the need to redesign future structures with additional reserves for strength and fatigue.

The results of such studies can serve as a basis for updating the regulatory framework by including additional fatigue assessment criteria that take into account the actual longitudinal loads during operation.

This study presents a simulation model for determining the forces that occur in the couplers during braking. It was developed by using the MATLAB Simulink® version R2015a software product. The train model is developed with all the forces that act on every single vehicle during its movement on the railroad. The main resistance forces accompanying the movement of the train are derived based on known equations presented below. The specific feature of this study is that the braking force is calculated based on the results about the pressure developed in the brake cylinder from a test bench for gas-dynamic simulation of braking processes. This allows us to take into account the real non-stationarity of the braking process, which is the main cause of large longitudinal forces.

2. Simulation Model for Studying the Longitudinal Train Dynamics

The main approach of this research is to choose a suitable dynamical model [

1,

20,

21] describing the motion of the train in the longitudinal direction. All the forces which act on a single vehicle must be determined and solved. When using multi-mass model [

1,

22,

23], it is usually assumed that the train is composed of “n” number of vehicles that are connected by couplers with elastic and damping characteristics. For developing the model that describes the behavior of a train set in braking mode, the MATLAB Simulink

® version R2015a software is used. The model consists of a locomotive and 43 wagons. It is schematically presented in

Figure 1:

mi is the masses of individual vehicles, and ai is its acceleration. The forces shown in the figure are, respectively, as follows:

- -

Bc,i—braking force, kN;

- -

W0,i—resistance force from the main resistance, kN;

- -

WR,i—resistance force from the curve, kN;

- -

Wi,i—resistance force from the road slope, kN;

- -

Fi—forces in the inter-car connections, kN.

The couplers are represented as elastic elements with damping characteristics. They have an elasticity coefficient ki and a damping coefficient ci. For the sake of simplicity, the vertical and transverse forces are neglected [

1]. The differential equation of motion for each car, if there are linear characteristics, is as follows [

1]:

where

xi—vehicle displacement, m;

vi—vehicle velocity, m/s.

To solve the equations describing the motion of the train, it is necessary to clarify the nature of all the forces acting on it.

2.1. Braking Force

From the literature review on longitudinal train dynamics [

3,

24,

25], it can be concluded that the main approach for determining the braking force of each vehicle in the train set is performed through theoretical simulation of the gas-dynamic processes in braking or by empirical functions [

26]. For modeling the braking force of an individual railway vehicle, this study uses data from the test bench, which represents the pneumatic part of train set consisting of 44 cars. The test bench is located in the laboratory of the Department of Railway Engineering at the Technical University of Sofia and is shown in

Figure 2:

The main components of the test bench are the (1) structural frame; (2) brake pipe; (3) distributor valve; (4) brake cylinder; (5) driver’s brake valve; (6) auxiliary reservoir; (7) air compressor; and (8) measuring system.

By using a measuring system developed in Ref. [

27], data about the change in brake cylinder pressure specified in time for each wagon are recorded. These results are processed in Excel in tabular form, which is appropriate for using them in the model created in Simulink

® to determine the braking distance and speed of individual wagons for each time of its motion. The braking model and the results obtained have already been published in Ref. [

28].

2.2. Retardation Force

The main resistance impact on each individual railway car of the train set traveling on a straight horizontal section of the track is given by Equation (2). This is the resistance force that acts throughout the entire movement of the train and includes the resistance from friction in the axle bearings, sliding and rolling of the wheels on the rails, and air resistance. It is usually calculated based on second-degree formulas experimentally derived for different types of rolling stock. They have the following form [

29]:

where

Coefficients A and B describe the impact of the mass movement on the resistance and the mechanical component of the interaction with the track [

29];

Coefficient C defines the effect of the aerodynamic resistance or the air resistance on the movement [

29].

2.3. Retardation Force Due to the Track Topography

This study was conducted by simulating the motion of a train along a straight horizontal section of the railroad. This means that the resistance forces from the slope and curve are neglected and are equal to zero.

2.4. Modeling the Couplers

To represent the train behavior accurately in the simulation model in Simulink

®, the real characteristics of the couplers [

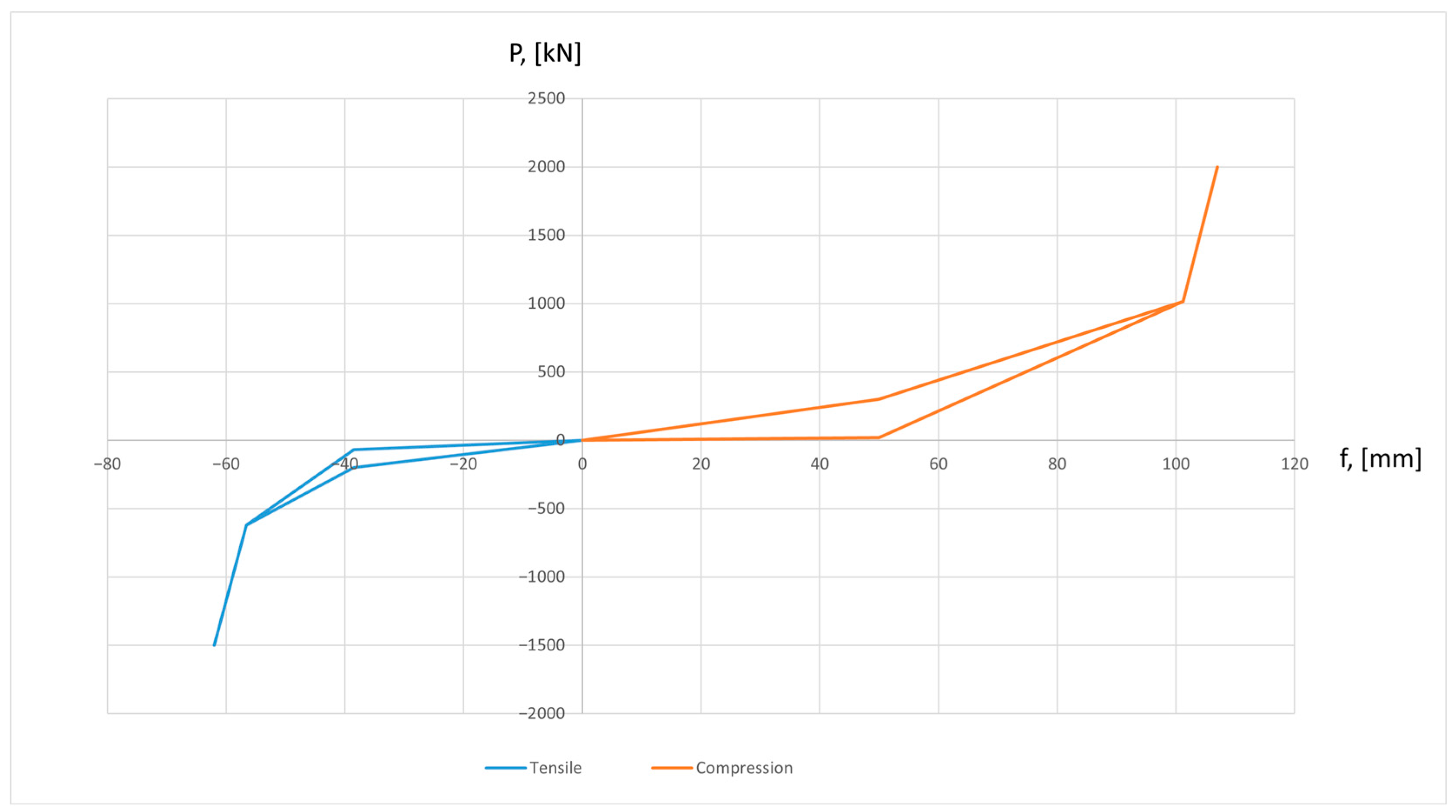

30] have been modeled. An energy absorbing element is with a nonlinear force characteristic. This characteristic represents the dependence between the force in coupler P and the coupler displacement f. It is shown in

Figure 3:

As can be seen from the figure, the two force characteristics of the buffer and the drawbar differ slightly from the real ones (they have a truncated appearance). This is because in this model they are presented at three points. They are, respectively, at the beginning, middle, and end of the coupler stroke. This was performed to simplify the model, which will significantly reduce the calculation time and at the same time will not significantly affect the results. When the coupler maximum stroke is reached, the load curve of the main frame begins. It is determined according to Ref. [

13], where the maximum longitudinal load in tension is set to be 1.5 MN, and in compression to be 2 MN. At these forces, the corresponding deformations in the main frame of the wagon structure are considered. The last part of the graph is made taking into account the stiffness of a wagon structure in the longitudinal direction, which was determined through a strength-deformation analysis of various wagon structures using the finite element method, and an arithmetic mean value was taken.

3. Results

The simulation results are derived based on the following initial parameters of the train set and its braking system:

- -

The train consists of 44 railway cars, each of which weighs 80 t (loaded wagon);

- -

The motion is simulated on a straight horizontal section of the road;

- -

The speed at which braking begins is 80 km/h;

- -

Simulations were performed at full-service braking and emergency braking;

- -

The two positions of operation of the distributor valve and mixed mode were considered.

3.1. Position “G”

In full-service braking (ninth position of the Knorr D2 driver’s brake valve), the first impacts between the wagons are observed when the train length exceeds 35 wagons. With this train length, the maximum longitudinal forces do not exceed 104 kN (for a 35-wagon train). Impacts between the wagons in a longer train lead to local significant forces in the couplers, reaching up to 344 kN for a 44-wagon train. The impacts begin after the 10th wagon and are observed up to the 31st wagon of the train. Compared to the 35-wagon train, the increase in forces is over three times. The development of longitudinal forces F in time for a 44-wagon train is shown in

Figure 4.

In short train sets (up to 20 wagons), where no large delays in the braking signal are observed, the longitudinal forces are entirely in the positive direction (tension). For more than 20 wagons, due to the delay of the braking wave, the forces are negative (compression).

Emergency braking is generally a mode in which the highest values of longitudinal forces are observed. Compared to full-service braking, the increase is of the order of 50 kN. Again, the nature of the change in forces is smooth in train sets with a length of up to 35 wagons; however, in longer ones, impacts are observed between the wagons located in the middle of the train. Another thing that is observed from the results is a difference in the response of the distributor valve of the individual wagons. The braking systems do not operate sequentially along the length of the train but chaotically. This leads to a change in the direction of the longitudinal forces. At the beginning of the braking process, there are compression and impacts between the wagons (for long trains). Then, it passes into tension and a smoother distribution of forces along the length of the train. The compression forces are much greater due to the impacts between the wagons, with the maximum force reaching 385 kN at the 27th wagon connection. This can be seen in

Figure 5.

3.2. Position “P”

This position of operation of the distributor valve is not typical for freight trains. There are significantly larger longitudinal forces compared to those in “G” mode. They are the result of the very large differences in the time it takes for a braking signal to travel to the specific wagon. The first wagons, due to the short distance from the driver’s brake valve, stop quickly, and gradually the brake signal lags along the train’s length. The lag becomes significant in the wagons located at the end of the train. This is confirmed by the results regarding the pressure in the brake cylinder specified in time as presented in

Figure 6.

At full-service braking maximum forces occur in the train set with the longest length, and they have a value of 395 kN. The period of action of the impacts between the wagons is 17.9 s. Also, in this position of the driver’s brake valve, impacts between the wagons are observed after the train set length exceeds 20 wagons. Up to this length, the nature of the longitudinal forces is smooth, and the values do not exceed 105 kN. The first impacts are observed in a train set with 25 wagons, in which the forces in the coupler go up to 345 kN and the impact time goes from 10.81 s to 18.5 s. This comparison shows that, regardless of the length of the train set (whether it is 25 or 44 wagons long), the values of the maximum longitudinal forces do not have a significant difference (50 kN). However, the impact time increases significantly with the increase in the number of wagons, which is clearly visible in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

In “G” position of the distributor valve, the largest longitudinal forces are obtained during emergency braking. Similar severe loads are observed in position “P”. Maximum longitudinal forces reach 512 kN for a train set with a length of 44 wagons. At this length of the train, impacts between the wagons are again observed which, in this case, are not the cause of the highest forces. They occur in coupler No. 17, in which the nature of the force change over time is smooth. This can be seen in

Figure 9.

The figure shows that, at the time from 17.75 s to 19.14 s, there are impacts between the two adjacent cars due to the differences in the maximum pressure of the individual brake cylinders. These impacts do not lead to achieving large longitudinal forces.

3.3. First 22 Wagons Are in “G” Position of the Distributor Valve, the Rest Are in “P” Position

Theoretically, this brake control strategy should compensate for the delay of the brake wave. This would lead to a drastic reduction in the longitudinal forces received in the couplers. The study was conducted at the test bench in

Figure 2. The distributor valves of the first 22 cars operate in the “G” position, and the remaining 22 in the “P” position. The results of the tests are shown in

Figure 10.

The figure shows that the individual pressure curves in the brake cylinders are more collected compared to those shown in

Figure 6, with all the wagons in the “P” position. The difference in the time for reaching the maximum pressure of the first and forty-fourth wagons in this case is 10 s. If all distributor valves are in the “P” mode, this difference is 20 s. Compared to a train set operating in the “G” position, the difference is 10.4 s. This shows that the obtained results should not differ from those obtained for a train set whose distributor valves of the wagons operate entirely in the “G” mode. The results of the calculations are shown in

Figure 11.

The figure shows that the maximum longitudinal forces occur in the middle of the train between the 22nd and 23rd wagons reaching 360 kN. The nature of the change in the longitudinal forces is close to the results obtained for a train set with distributor valve operating in the “G” position (

Figure 4). This is due to the identical change in the pressure in the brake cylinders in the two cases considered.

4. Discussion

The analysis of the results shows that the optimal mode of the distributor valve for long freight trains is the “G” position. The highest values of the longitudinal forces are obtained during emergency stopping with the driver’s brake valve, and it does not exceed 380 kN. Impacts between the wagons (the curly part of the graph) are characteristic of train lengths of over 35 wagons.

In the “P” position, the greatest values of the longitudinal forces are also obtained during emergency braking and reach 520 kN. Impacts between the wagons are obtained at a much shorter train length, which depends on the position of the driver’s brake valve. For full-service braking and emergency braking, this occurs when the train length exceeds 20 wagons.

In the mixed mode of operation of the distributor valves of the train set, there is no significant difference in the longitudinal forces compared to those in a train set that operates entirely in the “G” mode. This is because the pressure development in the braking cylinders does not differ much, unlike in the “P” position, where the difference is significant.

In the introduction, it was said that the higher values of longitudinal forces should be obtained during full-service braking due to lower speed of the propagation wave. But the results show that the higher forces occur during emergency braking. This can be explained with the speed of action of every distributor valve. The lower speed of propagation wave provides time for reaching the maximum pressure in brake cylinders with small differences for every vehicle in the train composition.

5. Conclusions

An in-depth study of the longitudinal train dynamics consisting of locomotive and 43 wagons has been conducted. The study reproduces the actual operation of the train set’s braking system in different braking modes, taking into account the non-uniform performance of the 44 distribution valves. The data are also linked to the real speed of propagation of the brake signal and, respectively, to the simulation of the operation of the brake system. The results of the above tests were used to create a computational model (results about the pressure brake cylinders) in MATLAB R2015a/Simulink® so that the longitudinal forces are calculated. The results about the longitudinal forces obtained from the study can be used in future developments to improve the control of the brake system in order to reduce the magnitude of the in-forces. The results can also be used to precisely define load cases in evaluating the rolling stock and its components, especially for fatigue assessment in the longitudinal direction.

In order to expand the research, it is also necessary to validate the computational model in a real train composition by measuring the real magnitude of the braking and coupler forces and comparing it with the calculated ones.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K., S.S., and V.M.; experimental studies, S.K., S.S., V.M., and M.V.; simulation model, S.K., S.S., P.S., and V.M.; data curation, S.K., S.S., P.S., and V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.S., V.M., P.S., and M.V.; visualization, S.K. and V.M.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science under the National Program “Young Scientists and Postdoctoral Students—2”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this study from the computational models are not publicly available due to commercial confidentiality and proprietary rights. Data may be made available upon reasonable request and with permission from the respective institutions.

Acknowledgments

The use of measuring equipment is supported by the Operational Program “Research, Innovation, and Digitalization for Smart Transformation 2021–2027” under Project NoBG16RFPR002-1.014-0006-C01, “National center of excellence for mechatronics and clean technologies”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Spiryagin, M.; Cole, C.; Sun, Y.Q.; McClanachan, M.; Spiryagin, V.; McSweeney, T. Design and Simulation of Rail Vehicles; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.B.; Jeong, R.; Kim, Y.; Chai, J. Comparisons Between Braking Experiments and Longitudinal Train Dynamics Using Friction Coefficient and Braking Pressure Modeling in a Freight Train. Open Transp. J. 2020, 14, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Q.; Ahmad, S.N.; Persson, I.; Spiryagin, M.; Arango, E.B.; Cole, C. Freight container wagon modelling and simulation analysis due to braking. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2024, 62, 3255–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velkov, K.; Krastev, O.; Purgić, S. About the process of braked weight loss in the freight trains. In Proceedings of the XVI Scientific-Expert Conference on Railways—RAILCON’14, Nis, Serbia, 9–10 October; 2014; pp. 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- UIC Code 540: 2002; Brakes—Air Brakes for Freight Trains and Passenger Trains. 4th ed. International Union of Railways: Paris, France, 2002.

- UIC Code 544-1: 2014; Brakes—Braking Power. 4th ed. International Union of Railways: Paris, France, 2014.

- Gfatter, G.; Berger, P.; Krause, G.; Vohla, G. Basics of Brake Technology; KNORR-BREMSE: Munchen, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pudovikov, O.E.; Murov, S.A. Simulation of regulating braking mode of long train. World Transp. Transp. 2015, 13, 28–33. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Lin, Y. Simulation of a freight train brake system with 120 valves. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2009, 223, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, B.; Pérez, J.Á. Comparative analysis of fatigue strength of a freight wagon frame. Weld. World 2024, 68, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, N.; Li, Z.; Dollevoet, R. Fast estimation of the derailment risk of a braking train in curves and turnouts. Int. J. Heavy Veh. Syst. 2016, 23, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BDS EN 12663-1:2010+A1:2015; Railway Applications—Structural Requirements of Railway Vehicle Bodies—Part 1: Locomotives and Passenger Rolling Stock (and Alternative Method for Freight Wagons). Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2015.

- BDS EN 12663-2:2010+A1:2023; Railway Applications—Structural Requirements of Railway Vehicle Bodies—Part 2: Freight Wagons. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2023.

- BDS EN 13749:2021+A1; Railway Applications—Wheelsets and Bogies—Method of Specifying the Structural Requirements of Bogie Frames. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2024.

- Xiu, R.; Spiryagin, M.; Wu, Q.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y. Fatigue life assessment methods for railway vehicle bogie frames. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 116, 104725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulewicz, R.; Nový, F.; Novák, P.; Palček, P. The investigation of the fatigue failure of passenger carriage draw-hook. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 104, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nový, F.; Jambor, M.; Petrů, M.; Trško, L.; Fintová, S.; Bokůvka, O. Investigation of the brittle fracture of the locomotive draw hook. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 105, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernescu, A.; Dumitru, I.; Faur, N.; Branzei, N.; Bogdan, R. The analysis of a damaged component from the connection system of the wagons. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2013, 29, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukšić Popović, M.; Tanasković, J.; Glišić, D.; Radović, N.; Franklin, F.J. Experimental and numerical research on the failure of railway vehicles coupling links. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 127, 105497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydov, Y.; Keyno, M. Longitudinal dynamics in connected trains. Procedia Eng. 2016, 165, 1490–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosso, N.; Magelli, M.; Zampieri, N. Long train dynamic simulation by means of a new in-house code. In WIT Transactions on The Built Environment; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2020; pp. 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwnicki, S. Handbook of Railway Vehicle Dynamics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cruceanu, C. Train Braking; InTech: Houston TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lovska, A.; Ravlyuk, V.; Elyazov, I. Determination of the load of a composite brake pad of a wagon with wedge-dual wear. In Proceedings of the 6th Annual Conference—Technology Transfer: Fundamental Principles and Innovative Technical Solutions, Tallinn, Estonia, 29 November 2022; pp. 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyulan, C.; Arslanm, E. Simulation and time-frequency analysis of the longitudinal train dynamics coupled with a nonlinear friction draft gear. Nonlinear Eng. 2020, 9, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosso, N.; Magelli, M.; Zampieri, N. A numerical method for the simulation of freight train emergency braking operations based on the UIC braked weight percentage. Rail. Eng. Sci. 2023, 31, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krastev, S.; Velkov, K.; Slavchev, S.; Maznichki, V. Measurement System for Determining the Main Pneumatic Parameters of Train Braking System. In Proceedings of the 13th International Scientific Conference on Aeronautics, Automotive and Railway Engineering and Technologies BulTrans-2021, Sozopol, Bulgaria, 10–13 September 2023; pp. 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Krastev, S.; Velkov, K.; Krastev, O. Simulation model for defining brake distance of rail vehicle. In Proceedings of the 13th International Scientific Conference on Aeronautics, Automotive and Railway Engineering and Technologies BulTrans-2021, Sozopol, Bulgaria, 10–13 September 2021; pp. 45–50. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Sapronova, S.Y.; Tkachenko, V.P.; Fomin, O.V.; Kulbovskiy, I.I.; Zub, E.P. Rail Vehicles: The Resistance to the Movement and the Controllability. Monograph; Ukrmetalurginform STA: Dnipro, Ukraine, 2017; p. 160. ISBN 978-966-921-163-7. [Google Scholar]

- ERRI B 51/RP 28; Draw and Buffing Gears Passenger coaches, Testing the Service Life of Hydrodynamic and Hydrostatic Coach buffers. European Rail Research Institute: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 1995.

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |