Abstract

The optimization of battery electric vehicles requires advanced high-strength steels that combine ductility and toughness, enabling lightweight leaf spring constructions with improved performance. This study investigates processing optimization by comparing the newly developed 45SiCrV9Ni, previously identified as promising for stress peening and fatigue, with the conventional 51CrV4 as a benchmark. Dilatometric, mechanical, and microstructural analyses were conducted in as-supplied and heat-treated conditions. Both steels show excellent high-temperature ductility, making them suitable for hot forming under similar conditions. However, 45SiCrV9Ni requires a higher temperature for homogenized austenitization. After tempering, it consistently exhibits superior hardness and toughness compared to 51CrV4. Importantly, its ductility remains nearly constant over a wide tempering temperature range, allowing lower ones to be chosen without compromising strength or toughness, offering additional energy-saving possibilities. These results highlight the potential of 45SiCrV9Ni for leaf spring applications.

1. Introduction

To optimize battery electric vehicles (BEVs), the development of ultralight, high-quality leaf springs that meet suspension requirements and withstand exceptionally high operational loads is a key factor. This target can be reached by the deployment of new high-strength steel grades with pronounced resistance to residual stress relaxation during operation in conjunction with advanced stress shot peening processes. Numerous studies have explored methods for increasing strength without compromising other properties, such as ductility and toughness, through approaches including modification of chemical composition [1], grain refinement [2], nanoparticle alloying [3], optimization of heat treatment [4], and cryogenic processes [5]. However, there remains a deficiency in understanding the interaction between optimized steels and surface treatments, specifically stress peening, a critical step in the production of leaf springs. An initial investigation into a newly developed leaf spring steel in [6] revealed highly promising fatigue properties compared to traditional leaf spring steels. This alloy, designated 45SiCrV9Ni, has also demonstrated excellent suitability for shot peening applications, evidenced by significant residual stress magnitudes and penetration depths, which are critical factors in spring applications. Consequently, the goal of this work is to further fundamentally study and optimize the processing of this advanced steel grade, to leverage its maximum potential for incorporation in fatigue-loaded applications, and to achieve enhanced performance in leaf springs of BEVs, while reducing the weight.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

This study aims to improve steel strength while reducing weight by examining two types of steel: the newly developed 45SiCrV9Ni and the conventional 51CrV4 as a reference. The novel 45SiCrV9Ni steel differs from 51CrV4 in three fundamental aspects: the inclusion of Si to increase strength and the incorporation of Ni along with a reduction in the C content to improve toughness. The chemical compositions of both materials are listed in Table 1. The materials in question were developed and produced by Sidenor. Initially, the scrap material was melted in an electric arc furnace, succeeded by processing in a ladle furnace. Subsequently, continuous casting was used to form billets of 185 , which were then subjected to hot rolling to fabricate flat bars of 90 × 31 .

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the two investigated spring steels.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Tensile Tests

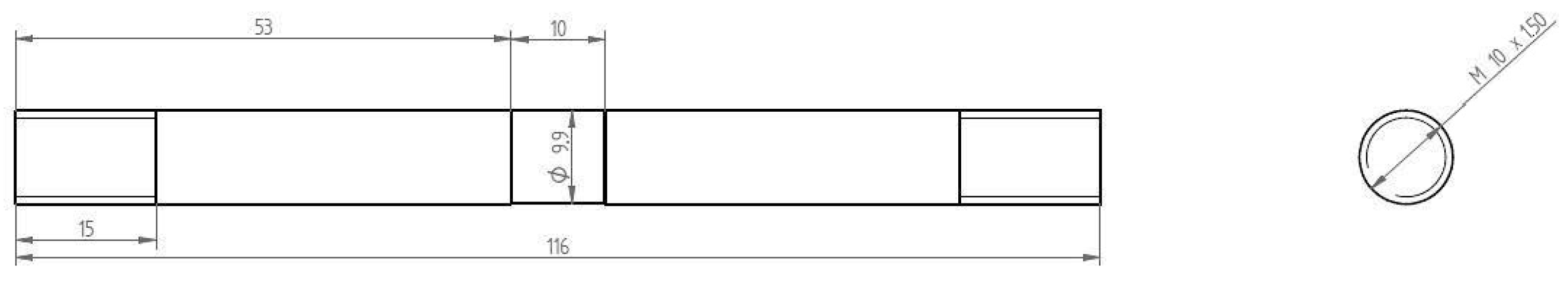

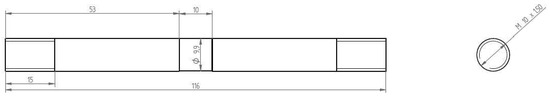

For the hot tensile tests, Gleeble 3800c thermomechanical equipment was used. The samples had the geometry shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Geometry of the Gleeble samples, with all dimensions indicated in .

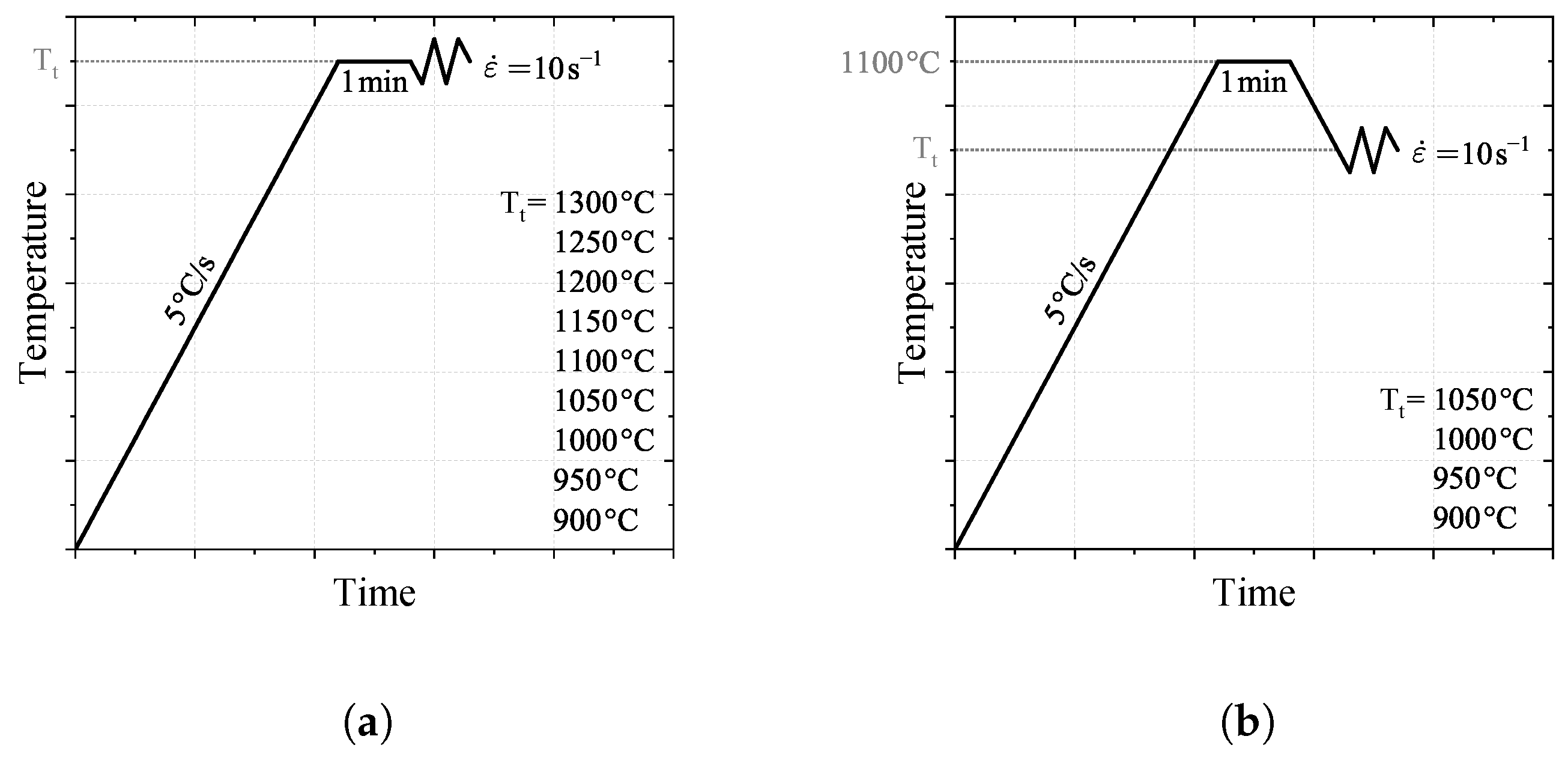

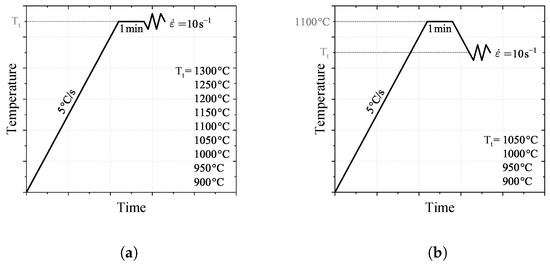

Figure 2 schematically shows the time–temperature diagram of the experiments. All specimens were heated at 5 °C until reaching the specified test temperature , where they were kept for a duration of 1 before starting the tensile test at a strain rate of 10 . The test temperatures were systematically varied between 900 °C and 1300 °C in increments of 50 °C. Furthermore, the lowest four test temperatures were examined during cooling, after 1 of austenitization at 1100 °C, with subsequent cooling to the test temperature at a rate of 1 °C. This approach was required because these test temperatures could not achieve proper homogenization, resulting in heating outcomes that might not accurately reflect industrial processes.

Figure 2.

Schematic course of the time–temperature diagram as a result of the hot tensile tests during (a) heating and (b) cooling.

Tensile tests of tempered samples at room temperature were performed according to the DIN EN ISO 6892-1 standard [7]. The samples had a diameter of 9 and a gauge length of 45 .

2.2.2. Dilatometer

A Bähr 805L dilatometer was used to determine the length change during heat treatments. The samples were 10 long and 4 in diameter. To develop a continuous cooling transformation (CCT) diagram for the novel alloy, ten samples were heated to a temperature of 1050 °C at a rate of 3 °C. The temperature was maintained for a duration of 5 before initiating the cooling process. The cooling rate was systematically altered for each sample in the range of °C to 20 °C, covering a spectrum of achievable microstructures.

2.2.3. Microscopy

Microstructure characterization was performed using an Olympus DSX500 optodigital microscope. During preparation, samples were polished with a 1 diamond solution and subsequently etched with Nital 3%.

2.2.4. Hardness Measurement

A Vickers KB 30 S hardness tester was used for the hardness measurements according to the DIN EN ISO 6507-1 standard [8]. The samples were prepared by polishing with 1 diamond solution.

3. Results

3.1. As-Supplied State

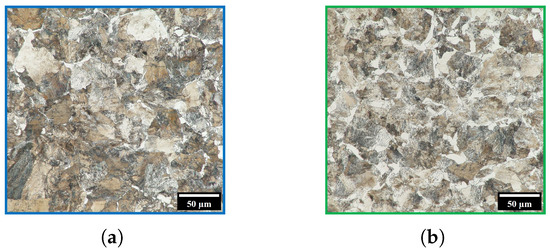

3.1.1. Microstructural Properties

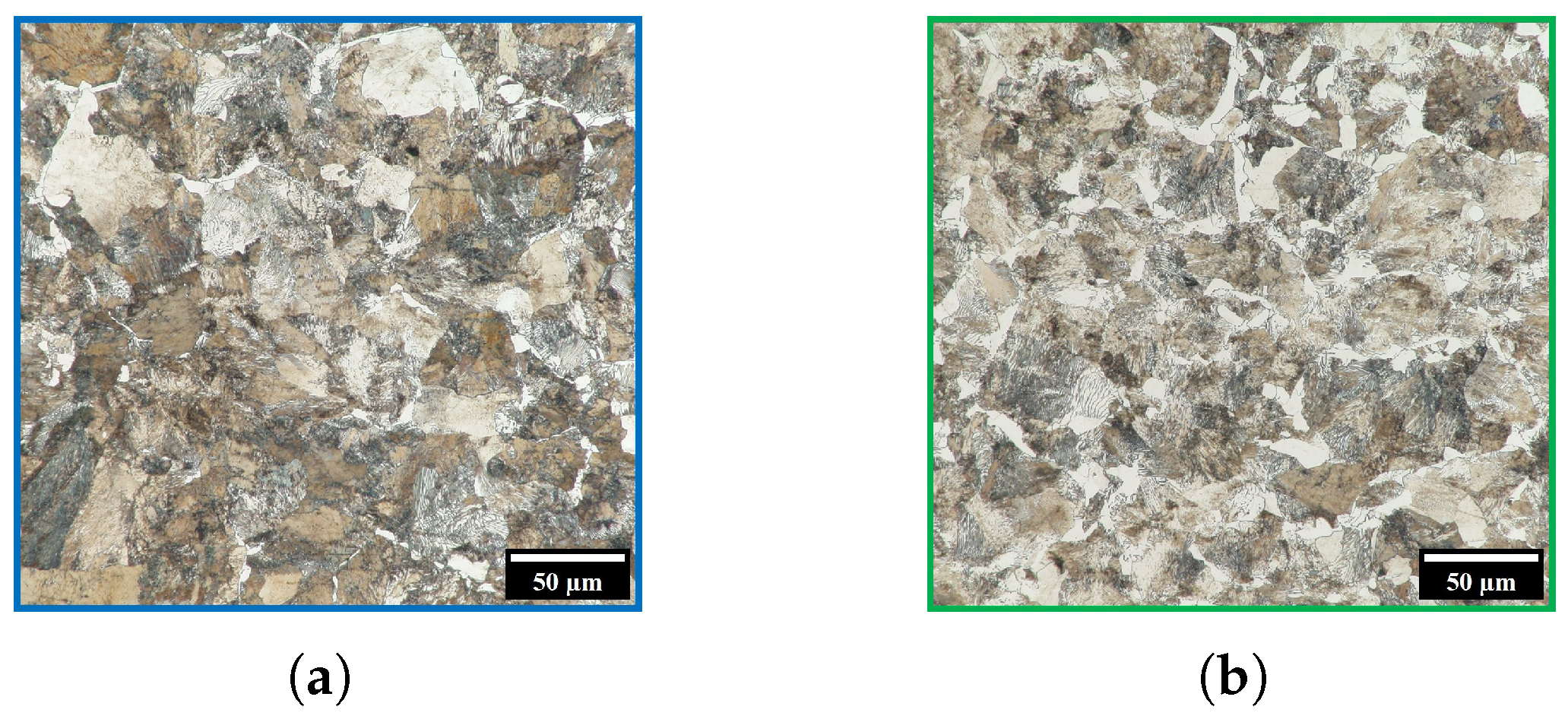

Initially, the microstructure and hardness of the supplied materials were examined using the methods mentioned in Section 2.2.3 and Section 2.2.4. Representative images at ×1000 magnification are presented in Figure 3. The standard alloy 51CrV4 comprises approximately 5% ferrite and 95% pearlite, resulting in a hardness of 304 ± 33 HV. In contrast, the new steel 45SiCrV9Ni possesses a higher proportion of ferrite with 15% and a reduced amount of pearlite with 85%, but its hardness is increased to 337 ± 34 HV. Furthermore, the microstructure of 45SiCrV9Ni appears to be finer compared to that of 51CrV4.

Figure 3.

Microstructure of as-supplied (a) 51CrV4 and (b) 45SiCrV9Ni at a magnification of ×1000.

3.1.2. Hot Strength Properties

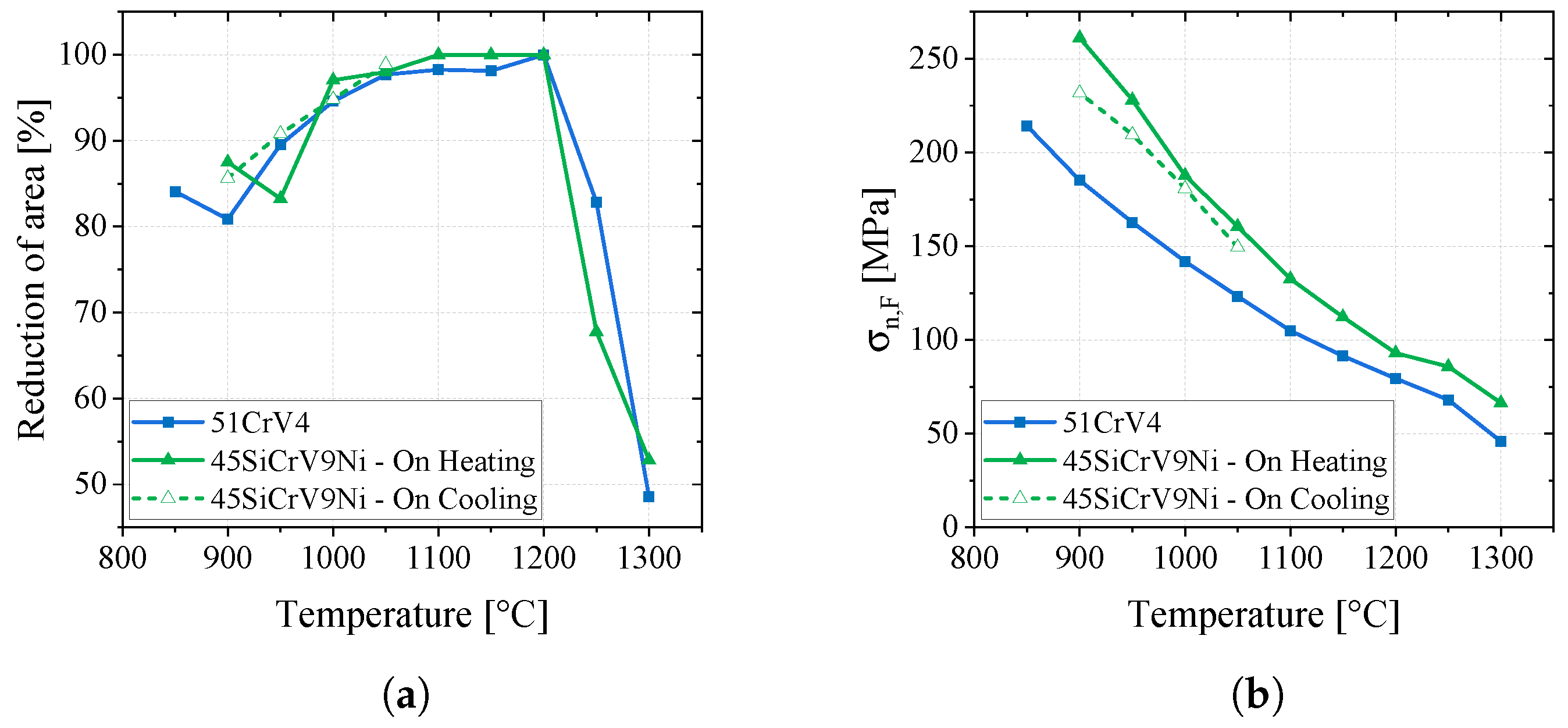

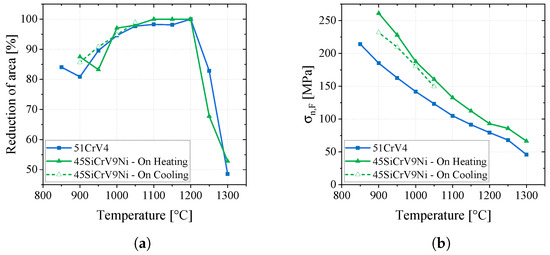

Hot tensile tests were conducted to assess the force needed for fracture and the ductility at elevated temperatures. As mentioned in Section 2.2.1, a Gleeble thermomechanical system was used, and the results are shown in Figure 4. Both materials exhibit comparable excellent ductility with at least 80% reduction in area up to 1200 °C, beyond which a marked decline in ductility is observed due to coarsening. This is corroborated by the fracture characteristics observed in Figure 5, where the 45SiCrV9Ni specimens are depicted post tensile test. In addition, 45SiCrV9Ni consistently requires a higher normal stress for fracture . However, this required stress decreases for both materials as the test temperature increases. It is important to emphasize that for 45SiCrV9Ni, the measurements during the cooling phase should be taken into account at lower temperatures in order to accurately reflect processing conditions.

Figure 4.

The results of hot tensile tests, showing (a) the reduction in area in %, and (b) the necessary stress for fracture, depending on the test temperature.

Figure 5.

Image of the 45SiCrV9Ni hot tensile test samples after the experiments, depicting their fracture behavior depending on the test temperature indicated below each sample.

3.2. Heat Treatment Optimization

A sequence of experiments was performed to optimize the heat treatment process of the newly developed alloy 45SiCrV9Ni, as elaborated in the subsequent sections.

3.2.1. Continuous Cooling Transformation (CCT) Diagram

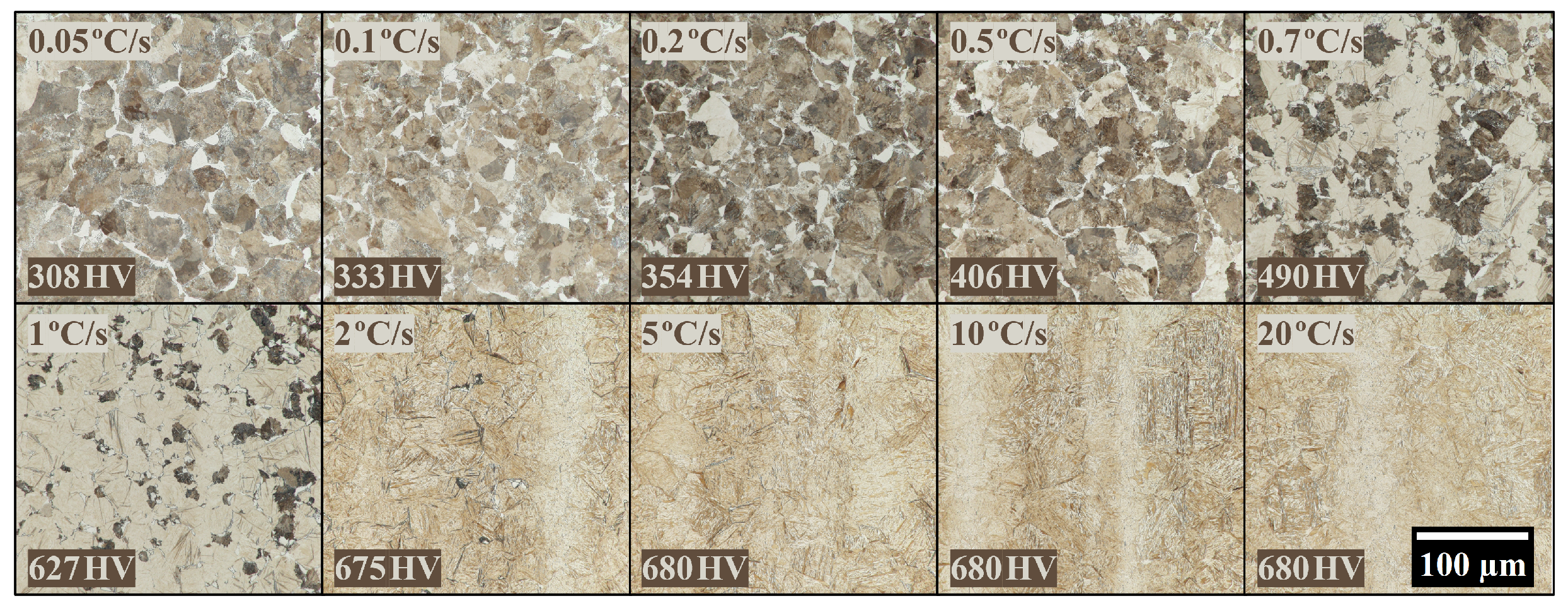

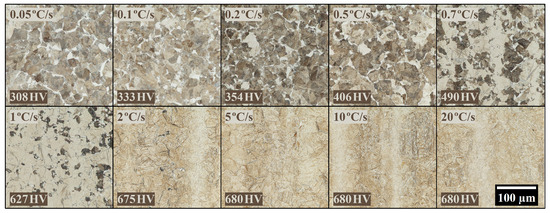

First, the CCT diagram of 45SiCrV9Ni was to be determined. Therefore, dilatometric experiments were performed as described in Section 2.2.2. The microstructures obtained at various cooling rates, along with their corresponding hardness values, are illustrated in Figure 6. An enhancement in hardness is evident with increased heating rates, attributable to the transition from a ferritic/pearlitic to a martensitic microstructure. At rates exceeding 5 °C, the hardness does not exhibit any further change, indicating the achievement of the maximum possible amount of martensite.

Figure 6.

OM images of the 45SiCrV9Ni dilatometric samples after different cooling rates, as well as the corresponding hardness values.

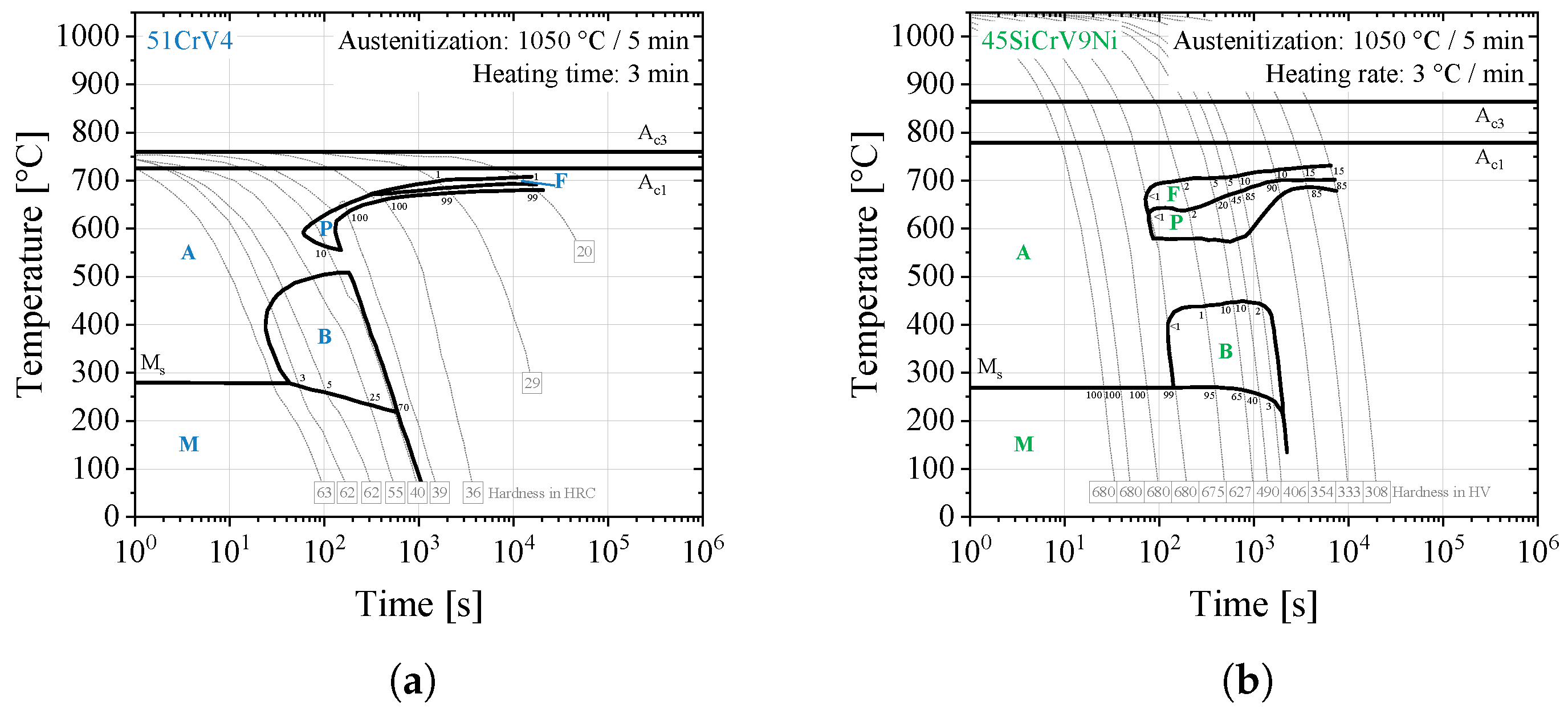

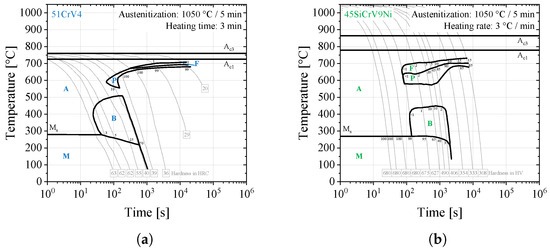

Using the dilatometric curves, as well as the microstructural and hardness characteristics of the samples, a CCT diagram was created for 45SiCrV9Ni, which is shown and compared with the CCT diagram of 51CrV4 from [9] in Figure 7. Both samples have the same martensite start temperature = 270 °C. The main difference is the lower critical cooling rate of 45SiCrV9Ni, as well as its higher transformation temperatures and .

Figure 7.

The CCT diagrams of (a) 51CrV4 51CrV4 reproduced with permission from Rose et al., Atlas zur Wärmebehandlung der Stähle – Band 1 – Teil 2 (1954) [9], published by Stahleisen, rights held by Maenken Kommunikation GmbH, and (b) 45SiCrV9Ni from the dilatometric investigations in this study.

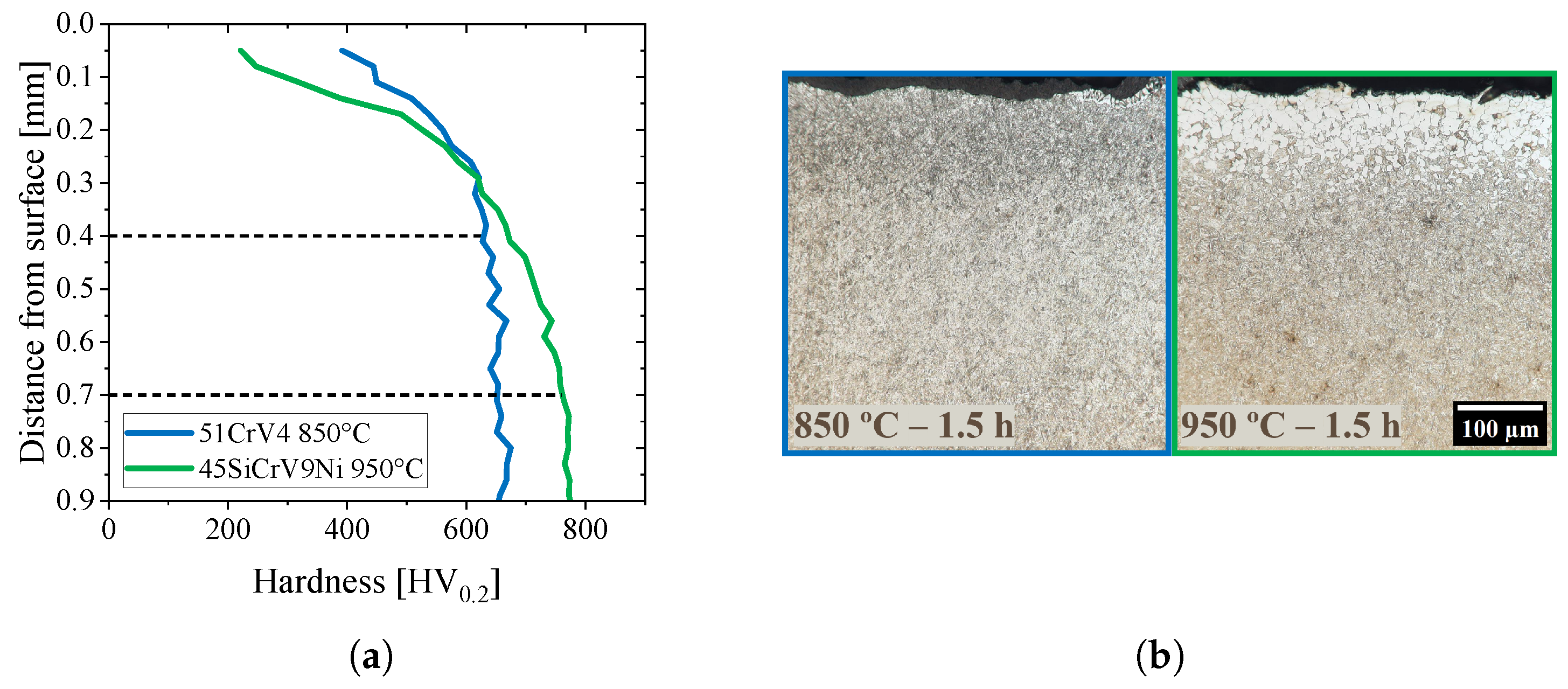

3.2.2. Austenitization and Decarburization

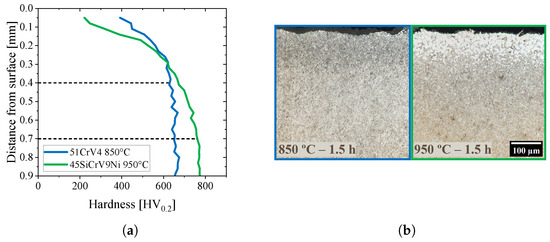

Given that decarburization can directly compromise the safety and performance of the springs by affecting their mechanical properties, it is crucial to analyze the impact of decarburization on the novel steel after austenitization. To determine the optimal austenitization temperature for 45SiCrV9Ni, the samples were first subjected to heat treatment at temperatures exceeding , specifically 875 °C and 900 °C. However, microstructural analysis revealed the presence of undissolved ferrite within the segregated bands at the core of the bar. Consequently, the austenitization temperature for the following investigations was set to 950 °C. For the verification of decarburization, 51CrV4 and 45SiCrV9Ni samples were austenitized for at 850 °C and 950 °C, respectively. The micrographs of the surface cross-section, as well as the hardness profiles starting at the surface toward the core of the material, are shown in Figure 8. The decarburized depth is about , and its influence can be seen in the hardness values up to for 51CrV4 and for 45SiCrV9Ni.

Figure 8.

(a) Hardness and (b) microstructure of 51CrV4 and 45SiCrV9Ni at the surface after austenitization, showing the decarburization depth, which is deeper for 45SiCrV9Ni.

3.2.3. Influence of Tempering

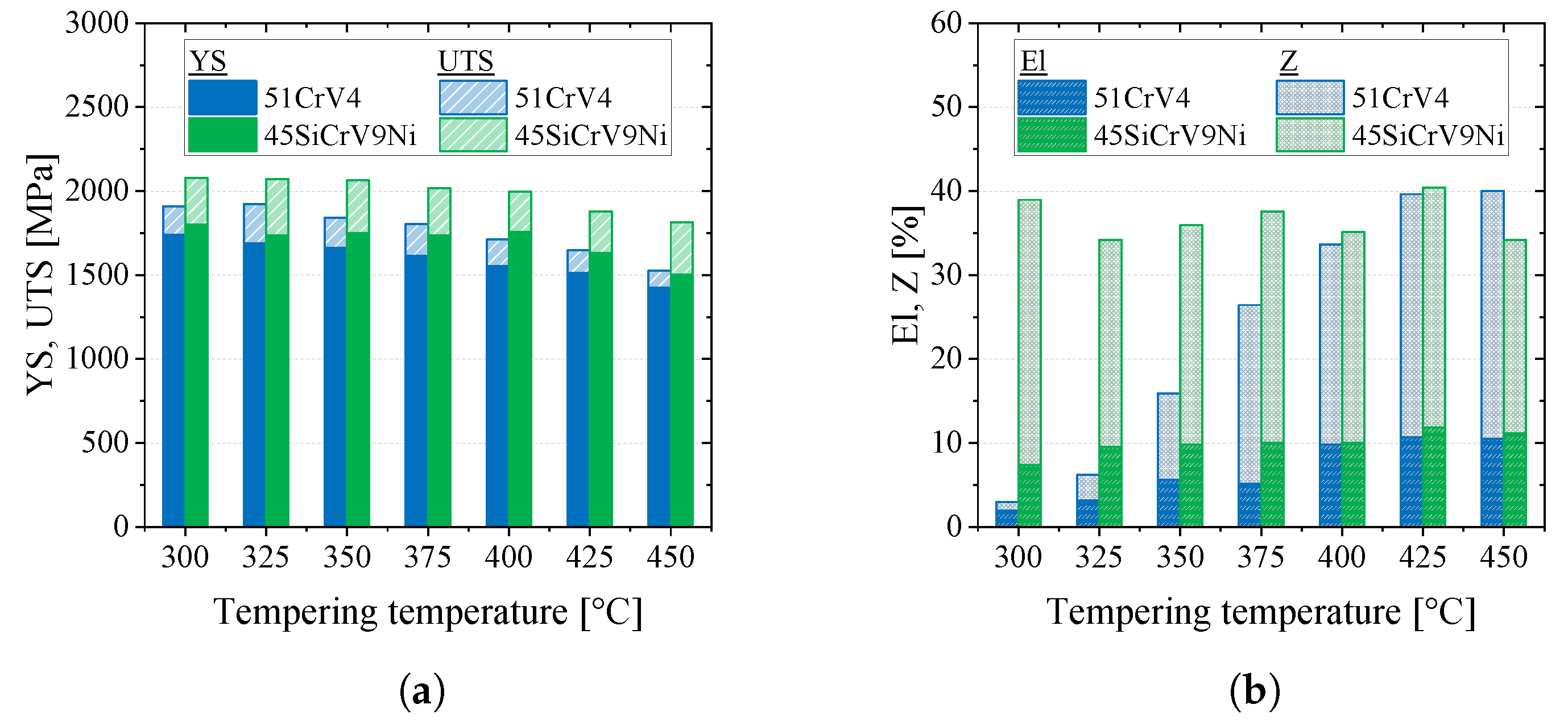

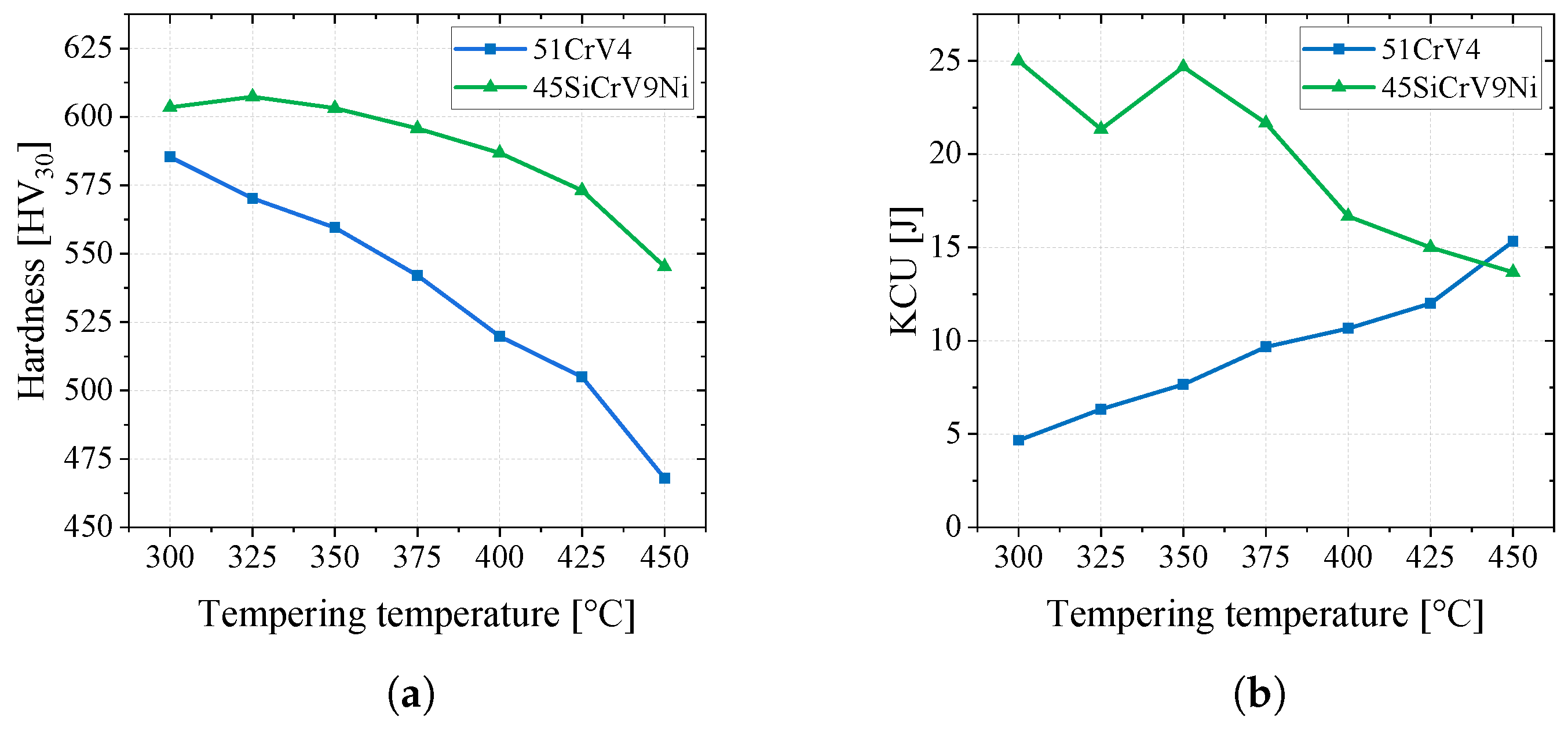

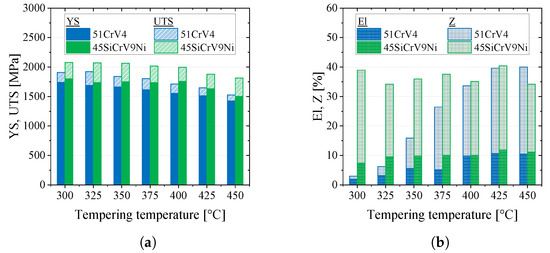

Different tempering temperatures between 300 °C and 450 °C were used on both materials and the impact of the heat treatment on strength, ductility, hardness, and toughness was investigated by using the methods mentioned in Section 2.2.1. Figure 9 illustrates the correlation between the tempering temperature and the strength, as well as ductility properties, for both materials.

Figure 9.

Influence of tempering temperature on (a) strength (ultimate tensile strength, UTS, and yield strength, YS) and (b) ductility (reduction in area, Z, and elongation, El) for both materials.

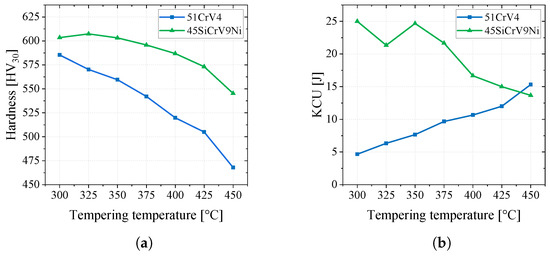

The 45SiCrV9Ni alloy consistently demonstrates higher ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and yield strength (YS) compared to 51CrV4. A decline in UTS and YS for 45SiCrV9Ni begins at 375 °C and 425 °C, respectively, while for 51CrV4, this decline occurs continuously. The reduction in area (Z) for the 45SiCrV9Ni alloy remains relatively constant between 30% and 40%, whereas the 51CrV4 alloy demonstrates a substantial increase in Z as the tempering temperature increases, ultimately achieving values comparable to those of 45SiCrV9Ni at 425 °C. The elongation (El) of 45SiCrV9Ni is predominantly constant, while 51CrV4 exhibits a slight increase in El with elevated tempering temperatures, achieving values similar to 45SiCrV9Ni from 400 °C. Figure 10 illustrates the relationship between tempering temperature and hardness and toughness for the materials under study. The hardness values exhibit a decrease for both materials, which is more pronounced in 51CrV4. In particular, 45SiCrV9Ni demonstrates superior hardness regardless of the tempering temperature. A noticeable reduction in charpy impact, KCU, is observed with increasing tempering temperature for 45SiCrV9Ni, while an increase is noted for 51CrV4. Furthermore, 45SiCrV9Ni consistently exhibits a higher charpy toughness than 51CrV4 up to 425 °C.

Figure 10.

Influence of tempering temperature on (a) hardness and (b) charpy impact toughness, KCU, for both materials.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

An investigation was conducted to optimize the processing parameters for two leaf spring steels: the new alloy 45SiCrV9Ni and the reference alloy 51CrV4. In terms of hot formability, both steels showed excellent ductility and can undergo hot forming under comparable conditions. However, the force required to form 45SiCrV9Ni is approximately 20% greater than that necessary to form 51CrV4. Additionally, the novel alloy necessitates a higher temperature for homogenization during austenitization. With regard to heat treatment, the conventional alloy 51CrV4 attains its best combination of strength, toughness, and ductility when tempered at a temperature of 425 °C. This balance is crucial as improvements in ductility and toughness are prioritized, necessitating acceptance of reduced strength and hardness. For the new alloy 45SiCrV9Ni, since its ductility remains substantially constant regardless of the tempering temperature, lower temperatures can be selected to achieve optimal strength and toughness while conserving energy. However, considering its subsequent application in leaf springs and the fact that they will undergo stress peening at 350 °C, the tempering temperature must exceed 350 °C. Consequently, 375 °C has been selected for further studies. In this condition (tempered at 375 °C), the properties of 45SiCrV9Ni surpass those of 51CrV4 in its optimal state (tempered at 425 °C). UTS and YS are elevated by 22% and 14%, respectively, with the hardness showing an increase of 18%. The charpy impact toughness demonstrates a substantial enhancement by 80%. Only ductility levels remain comparable, and 51CrV4 shows marginally higher values (5% to 6%) in Z and El. This minor increase is insignificant compared to the improvements in strength and resilience of 45SiCrV9Ni. The superior strength–toughness balance of 45SiCrV9Ni results from its optimized chemical composition compared to 51CrV4. Si strengthens the matrix through solid solution hardening [10] and suppresses the growth of austenite grains, leading to a finer microstructure resulting in grain boundary strengthening, while improving toughness by impeding crack propagation [11]. Ni further refines the martensitic structure by reducing the size of packets and blocks [12]. During tempering, Si retards cementite precipitation [13], helping to retain hardness and toughness. The lower C content decreases the fraction of interlath carbides, reducing crack initiation sites and thereby improving toughness [14]. Future studies will involve employing this steel in its optimized processing condition for application in leaf springs, akin to [15], to examine its fatigue and stress relaxation characteristics. Moreover, it is imperative to consider the decarburization depth throughout the manufacturing process of the leaf springs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N., B.E., C.G., R.E. and S.D.; methodology, B.E.; validation, B.E. and R.E.; formal analysis, B.E.; investigation, B.E.; resources, B.E.; data curation, N.N., B.E. and C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, N.N.; writing—review and editing, B.E., C.G., G.S., R.E., S.D. and V.S.; visualization, N.N. and B.E.; supervision, G.S., S.D. and V.S.; project administration, G.S.; funding acquisition, G.S., R.E., S.D. and V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Fund for Coal & Steel, Grant Agreement number 101156140, Steels for ultralight asymmetric leaf springs for battery electric trucks with resistance to relaxation of residual stresses – e-TRUCKS.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors B.E. and R.E. are employed by the company Sidenor I+D. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Podgornik, B.; Tehovnik, F.; Burja, J.; Senčič, B. Effect of Modifying the Chemical Composition on the Properties of Spring Steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2018, 49, 3283–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgornik, B.; Leskovšek, V.; Godec, M.; Senčič, B. Microstructure refinement and its effect on properties of spring steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 599, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgornik, B.; Torkar, M.; Burja, J.; Godec, M.; Senčič, B. Improving properties of spring steel through nano-particles alloying. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 638, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gong, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Ren, X.; Wang, E. Effect of Quenching Conditions on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of 51CrV4 Spring Steel. Metals 2018, 8, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, V.R.M.; Podgornik, B.; Leskovšek, V.; Totten, G.E.; Canale, L.D.C.F. Influence of Deep Cryogenic Treatment on the Mechanical Properties of Spring Steels. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2019, 28, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumpp, A.; Elvira, R.; Dapprich, S.; Dietrich, S.; Schulze, V. Effects of Shot Peening on Surface Layer States and Fatigue Behavior in Experimental Casts of Enhanced Leaf Spring Steels. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Shot Peening (ICSP14), Milan, Italy, 4–7 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- DIN EN ISO 6892-1; Metallische Werkstoffe-Zugversuch. DIN Media GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 6507-1; Metallische Werkstoffe-Härteprüfung nach Vickers. DIN Media GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.; Peter, W.; Strassburg, W.; Rademacher, L. Atlas zur Wärmebehandlung der Stähle-Band 1-Teil 2; Max—Planck-Institut für Eisenforschung in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Werkstoffausschuß des Vereins Deutscher Eisenhüttenleute: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, M.; Jing, K.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, R.; Li, G.; et al. Effect of Si content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of 9Cr-ferritic/martensitic steels. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2023, 35, 101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anya, C.; Baker, T. The effect of silicon on the grain size and the tensile properties of low carbon steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1989, 118, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, F. Influence of Nickel on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties in Medium-Carbon Spring Steel. Materials 2024, 17, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Borgenstam, A.; Stark, A.; Hedström, P. Effect of Si on bainitic transformation kinetics in steels explained by carbon partitioning, carbide formation, dislocation densities, and thermodynamic conditions. Mater. Charact. 2022, 185, 111774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Ye, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, G.; Wang, B. Effect of carbon content on microstructure and mechanical properties of hot-rolled low carbon 12Cr–Ni stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 7407–7412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaidis, A. Surface Properties and Fatigue Life of Stress Peened Leaves. Mater. Test. 2012, 54, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.