Abstract

This paper describes an example of a failure of the rotating support girder of a spreader bridge. The root cause of the damage was buckling of one of the girder’s plates. This caused plastic deformation, which made the continued safe operation of the machine impossible. An FEM analysis was performed to determine the probable cause of the failure. Conclusions and recommendations are also presented in the paper to prevent similar failures in the future.

1. Introduction

Large objects, such as excavators, stackers or stackers–reclaimers, are very large moving machines that are designed for long-term operation (usually intended to last for decades) [1]. Their weight reaches up to tens of thousands of tons. Such machines usually consist of a superstructure that is mounted on the substructure. The superstructure can rotate relative to the substructure. The substructure is a very important part of the machine when it comes to stability. If a part of the superstructure fails, it usually has less significant consequences than a failure in the substructure. As an example, we can point to a discharge boom suspension failure in a bucket wheel excavator, which did not cause complete or serious failure of the machine [2]. In contrast, a substructure failure usually results in the destruction of the entire machine, which puts the employees using it at risk of severe injury or death. Due to these machines’ very long periods of operation, about 90% of their failures are fatigue-related [3,4]. However, there are also known cases of failures resulting from damage caused by exceeding the strength of the material, loss of stability [5], or problems related to welded joints [6].

In the case of large objects, the phenomenon of buckling is particularly dangerous. It is characterized by an uncontrolled loss of stability by the elements from which the technical object is made. Slender structural elements are particularly susceptible to this phenomenon. Subjecting them to compressive loads can lead to buckling. This may lead to their destruction. This was the situation in the event analyzed in this paper. The phenomenon of buckling is well recognized in the literature. The paper [7] describes how operating and design errors impact cranes’ susceptibility to buckling. Similar aspects are described in the paper [8] with regard to pressure vessels. The paper [9] describes the influence of the wind on the possibility of buckling. An example of a buckling failure of the conveyor is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Belt conveyor failure due to buckling phenomena.

2. Object of the Research

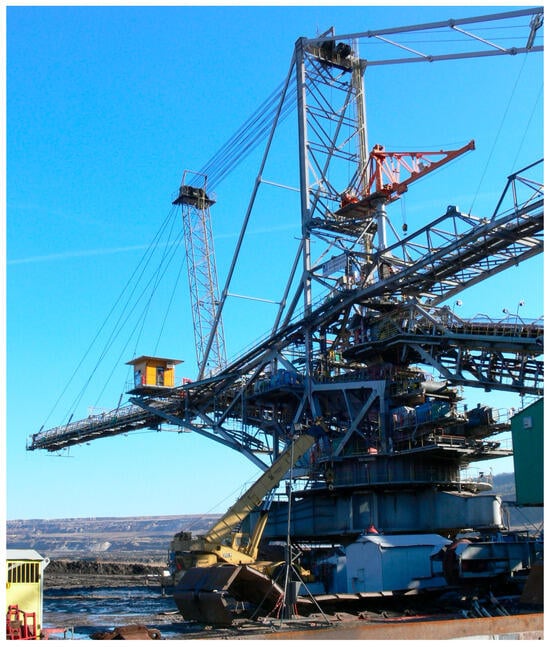

The research object was a stacker used in an open-cast mine. The purpose of this type of machinery is to transport the excavated material to a new storage site or to areas subject to reclamation. These machines are also used in bulk material storage areas, e.g., in seaports.

From a technical perspective, in open-cast mines, as well as in transshipment yards, these are key machines. Their failure makes it impossible to carry out the storage process in a given area. In extreme cases, this leads to the entire plant being unable to function. In the paper [10], an attempt was made to estimate the costs resulting from the failure of mining equipment that caused production to stop. Using the data available for the analyzed case, the costs accrued during the machine’s downtime were determined to be at the level of EUR 150/h, resulting from the inability to operate the mining or transshipment plant, which was solely and exclusively due to the lack of transport (ignoring other components).

The analyzed technical object was originally delivered by a German company in the 1980s. Since then, it has remained in operation. The machine type is A2RsB 12.500. During its operation, it underwent modifications and necessary overhauls. In Figure 2, the entire technical object is presented, including the spreader and bridge.

Figure 2.

A2RsB 12.500 spreader.

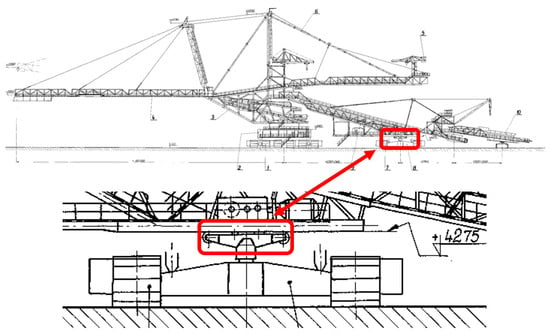

The failure described in the article concerns a relatively small part of the entire machine. The damaged component is part of the support system of the loading bridge. Its location in relation to the entire machine is shown in Figure 3. The rotating support girder is an element that connects the substructure of the bridge to its main carrying structure. It allows for the relative movement of the substructure and superstructure in the following directions: translation along the machine axis, rotation around the substructure, and inclination to compensate for height differences in the stacker substructure. It is important, from the point of view of further work, to note that the support system prevents rotation along the axis of the entire machine.

Figure 3.

Rotating support girder location in relation to the entire machine.

3. Description of the Failure

The failure occurred during the normal operation of the technical object. At some point during the workday, the staff heard a loud noise. After a visual inspection of the integral parts of the machine was performed, a displacement of the trolley supporting the carrying structure of the loading bridge was observed. After preliminary analysis, it was determined that the rotating support girder was deformed. Therefore, a decision was made to dismantle it and find the root causes of the failure.

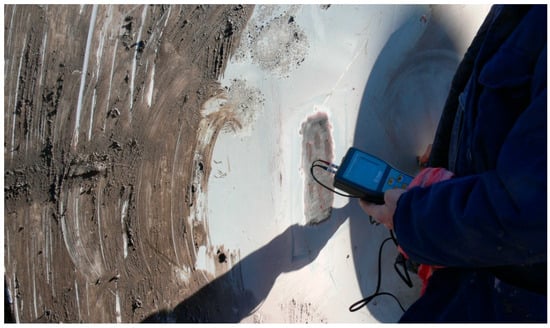

At first, NDT tests were carried out. Their aim was to provide information on two main issues. The first involved verifying whether there were cracks in the structure of the damaged element. The magnetic particle method was used for this purpose. It did not reveal any defects that could cause the described failure. The second issue concerned the correctness of the design and the corrosion phenomenon. For this purpose, thickness gauge measurements (Figure 4) of all components of the rotating support girder were provided. As was the case for the magnetic particle method, no problems were found—all dimensions were in accordance with the available technical documentation.

Figure 4.

TIEDE TM-11 thickness gauge used for rotating support girder measurements.

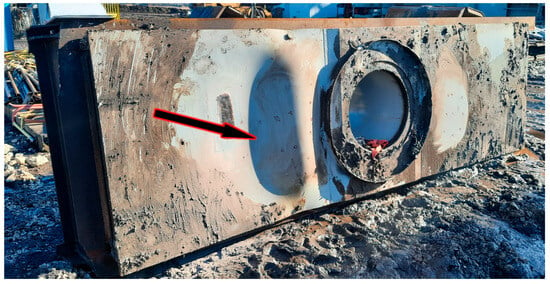

In Figure 5, a disassembled rotating support girder is presented. In the area marked by the arrow, plastic deformation is clearly visible. It has a characteristic shape that is typical of buckling forms in steel sheet structures [11]. With reference to the investigation from the previous paragraph, material defects, corrosion, and design inconsistencies should be excluded from the probable causes of failure. The tests performed did not show any deviations from the assumed parameters.

Figure 5.

The rotating support girder after disassembly. The buckling area is marked with a black-red arrow.

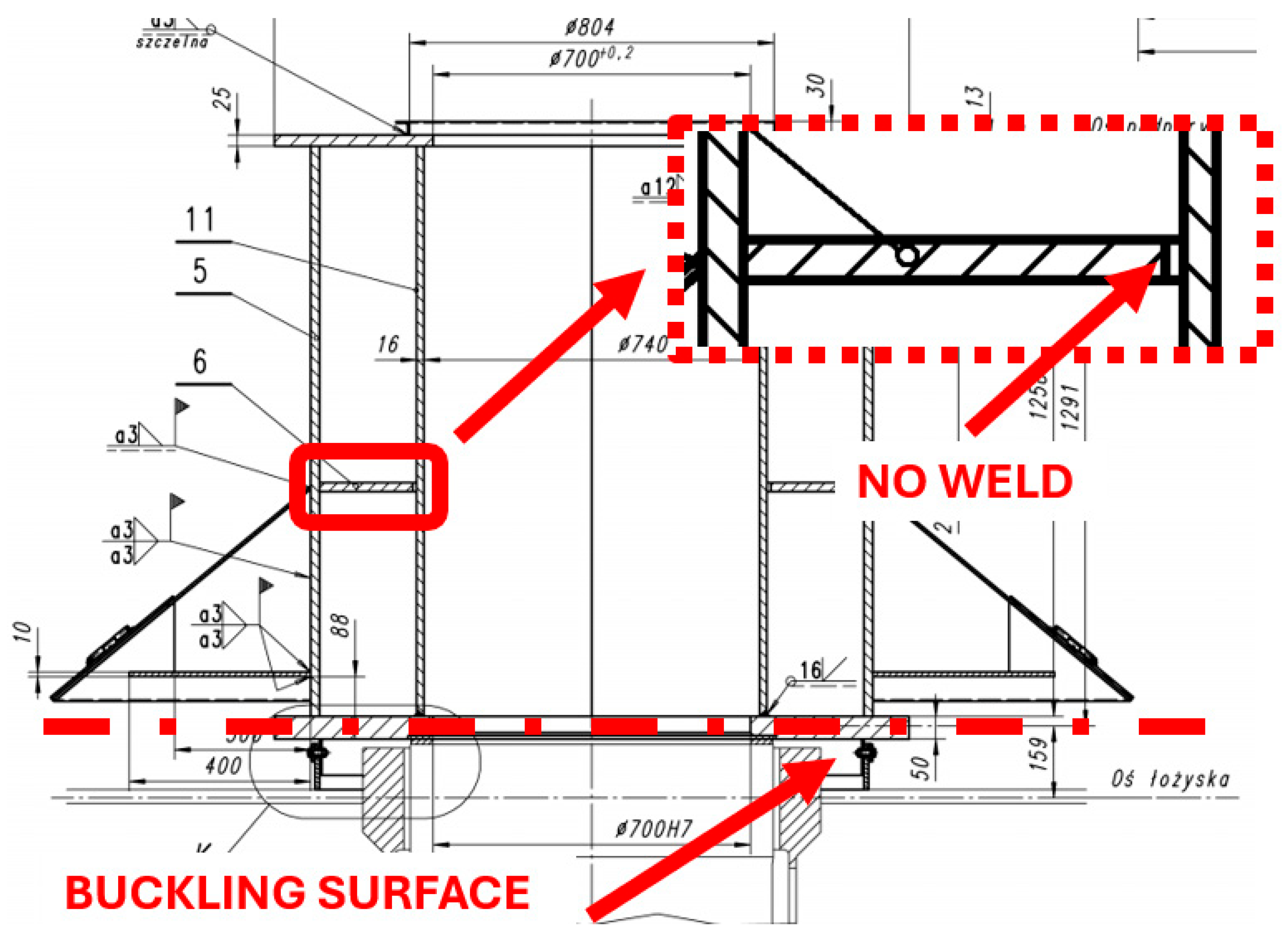

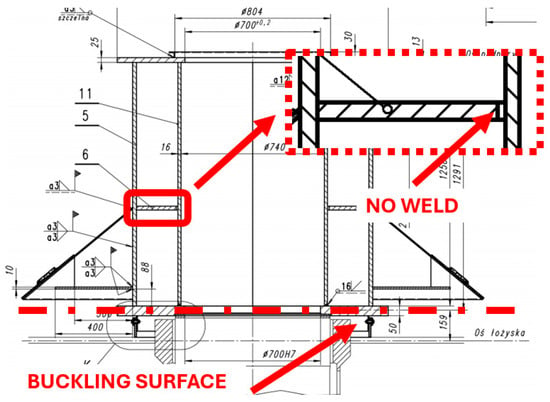

An analysis of the technical documentation of the deformed element revealed an area of interest, which is shown in Figure 6. The horizontal steel plate that forms the profile of the box section is not welded to the vertical tube of the drum that transfers vertical loads to the plain bearing. The purpose of this bearing is to allow the superstructure of the bridge to rotate in relation to its substructure. Such a construction solution significantly affects the stiffness of the entire structure. For this reason, we decided to perform an FEM analysis to verify the original design.

Figure 6.

Location of an incomplete connection (no weld) of the box section forming the rotation support girder.

4. Numerical Investigations

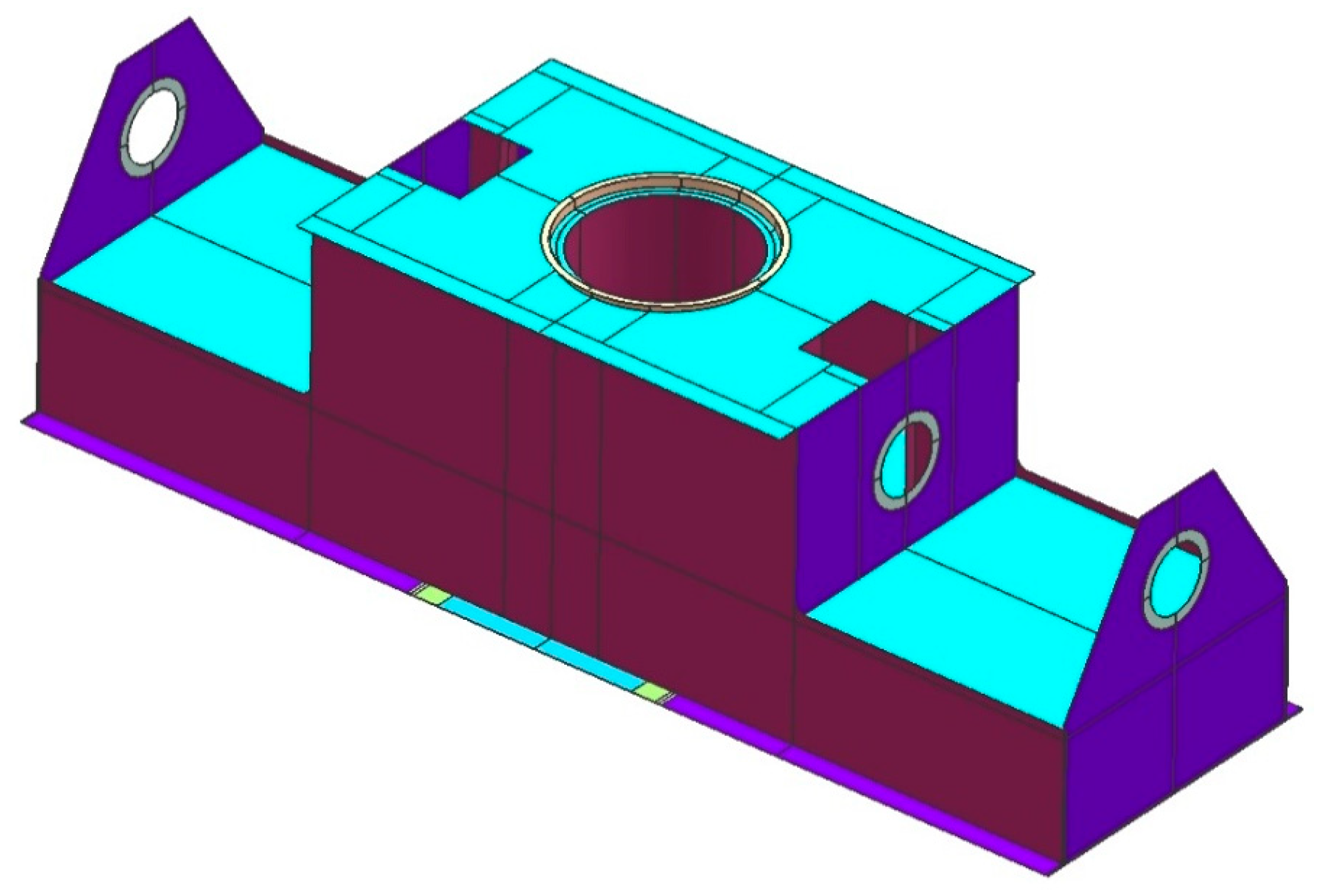

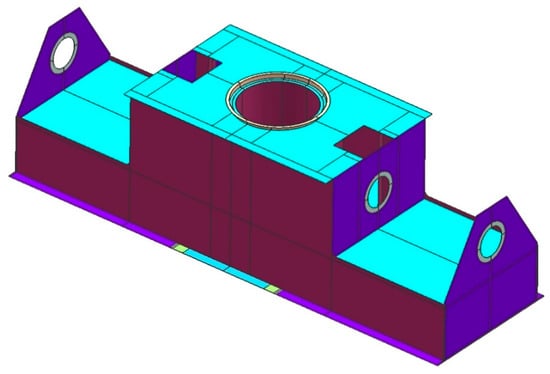

Numerical calculations were carried out in order to identify the causes of the buckling phenomenon. For this purpose, we created a geometric model of the analyzed object: the rotating support girder. The model was made using the surface technique. In Figure 7, the geometric model is shown. It was created according to the available technical documentation. Based on the geometric model, a discrete model was developed. It consisted of the following types of finite elements: shell, beam, and rigid. In total, 40,412 finite elements were used to build the model. Structural steel with a yield strength of Re = 355 MPa was adopted as the material model. The calculations were performed based on the Polish standard used in this type of machine. It is marked with the symbol PN-G-47000-2 [12] and is similar to the DIN 22261-2:1997 standard [13], which is widely used in this industry.

Figure 7.

Geometrical model of the rotating support girder.

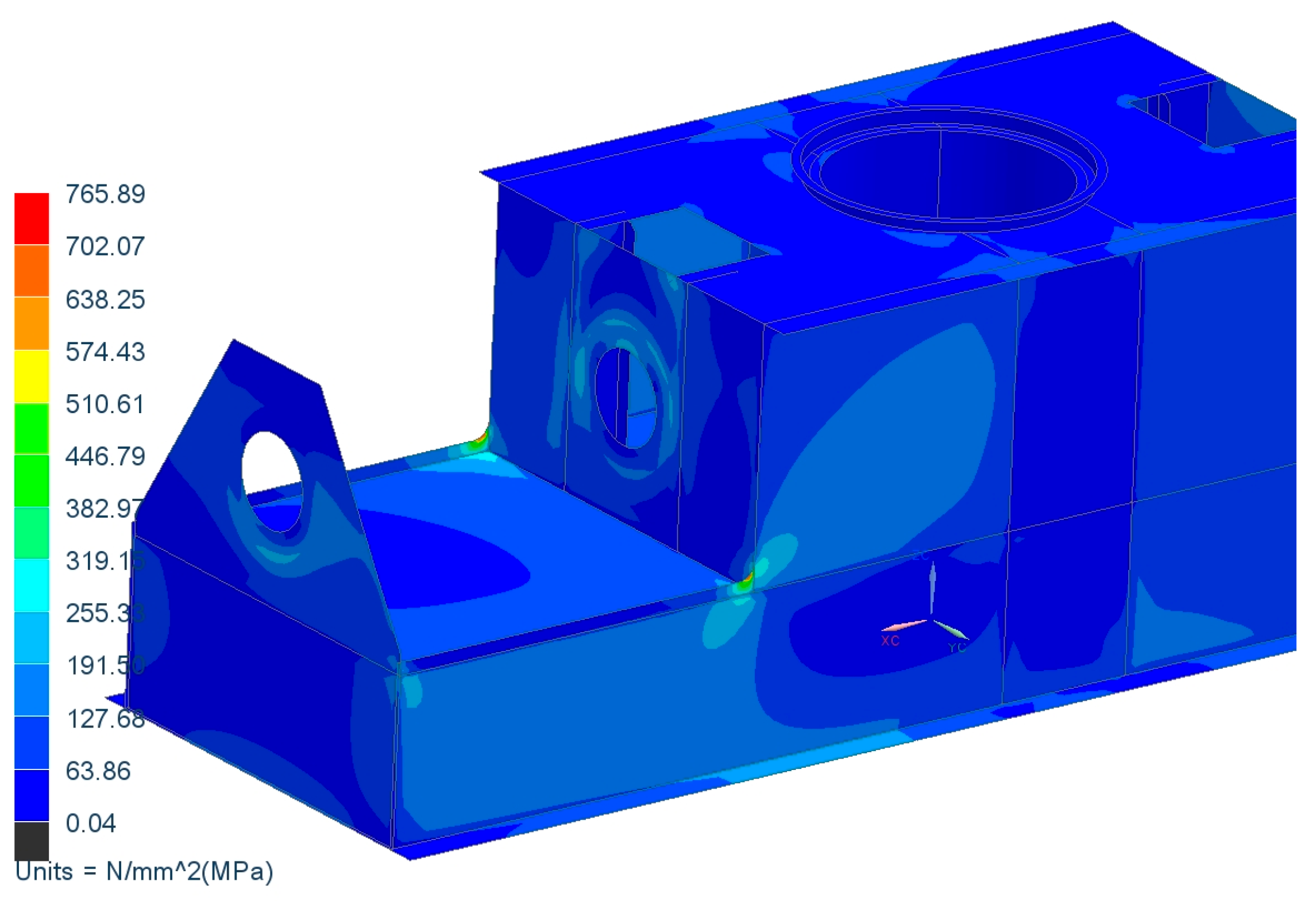

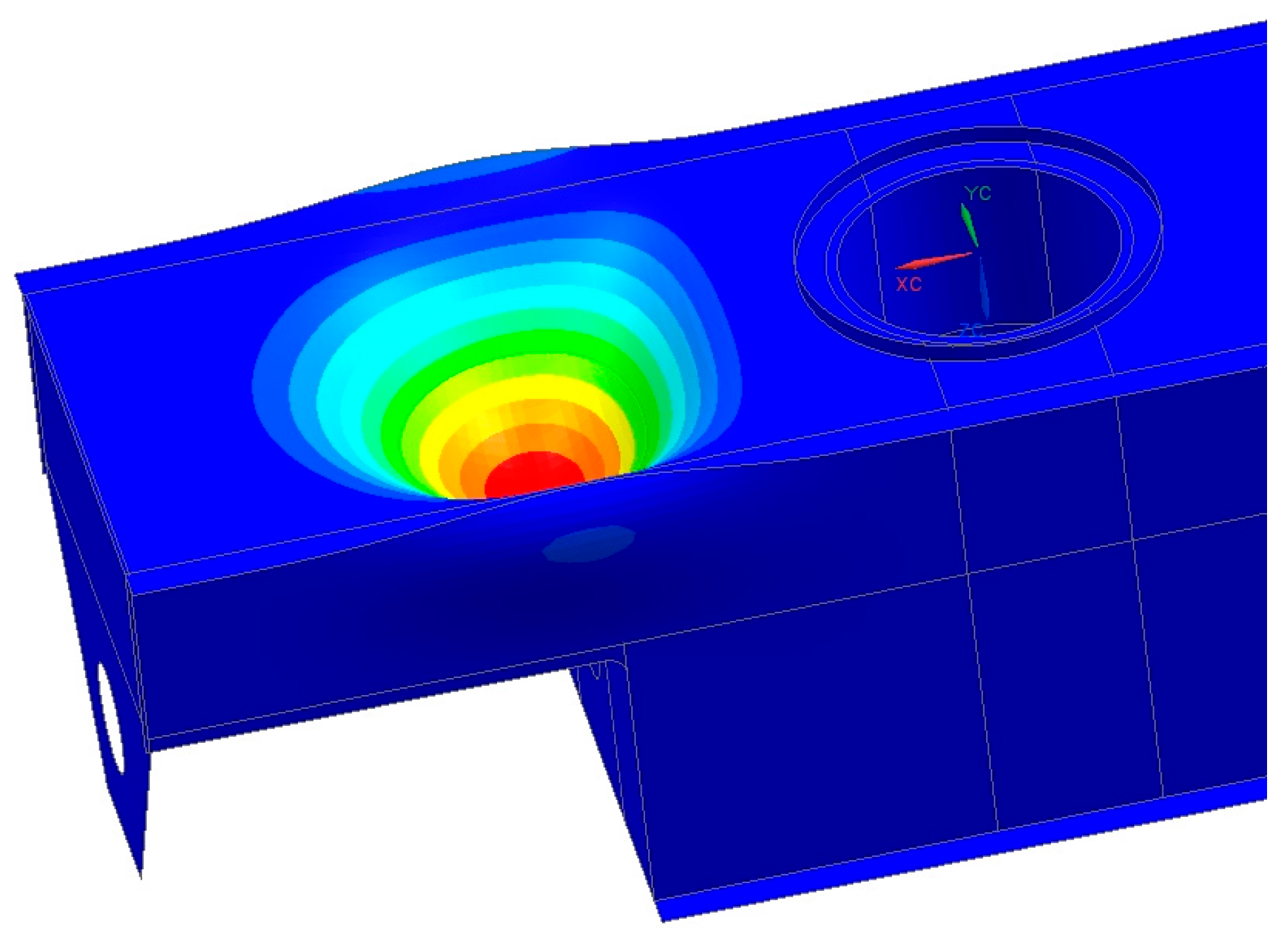

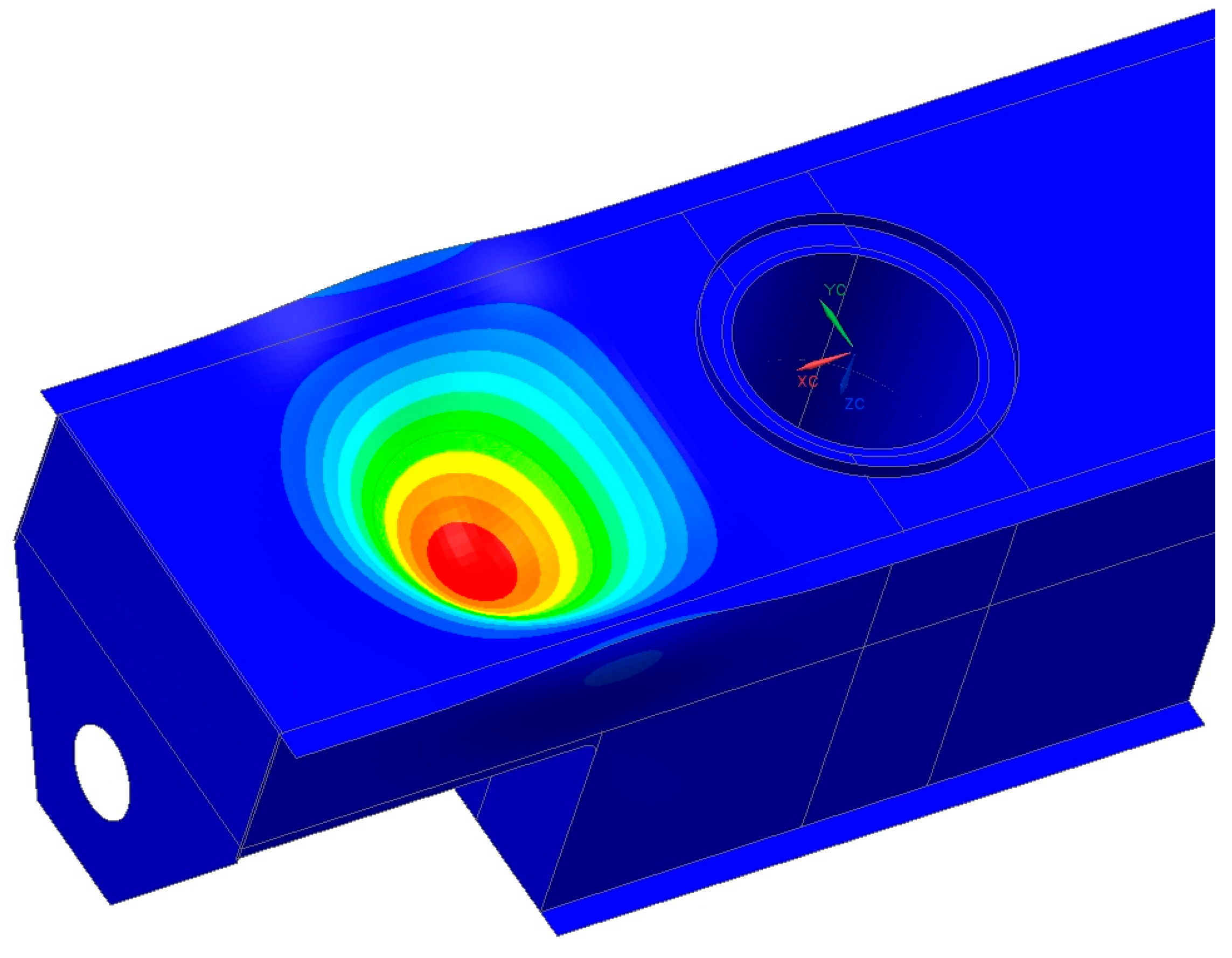

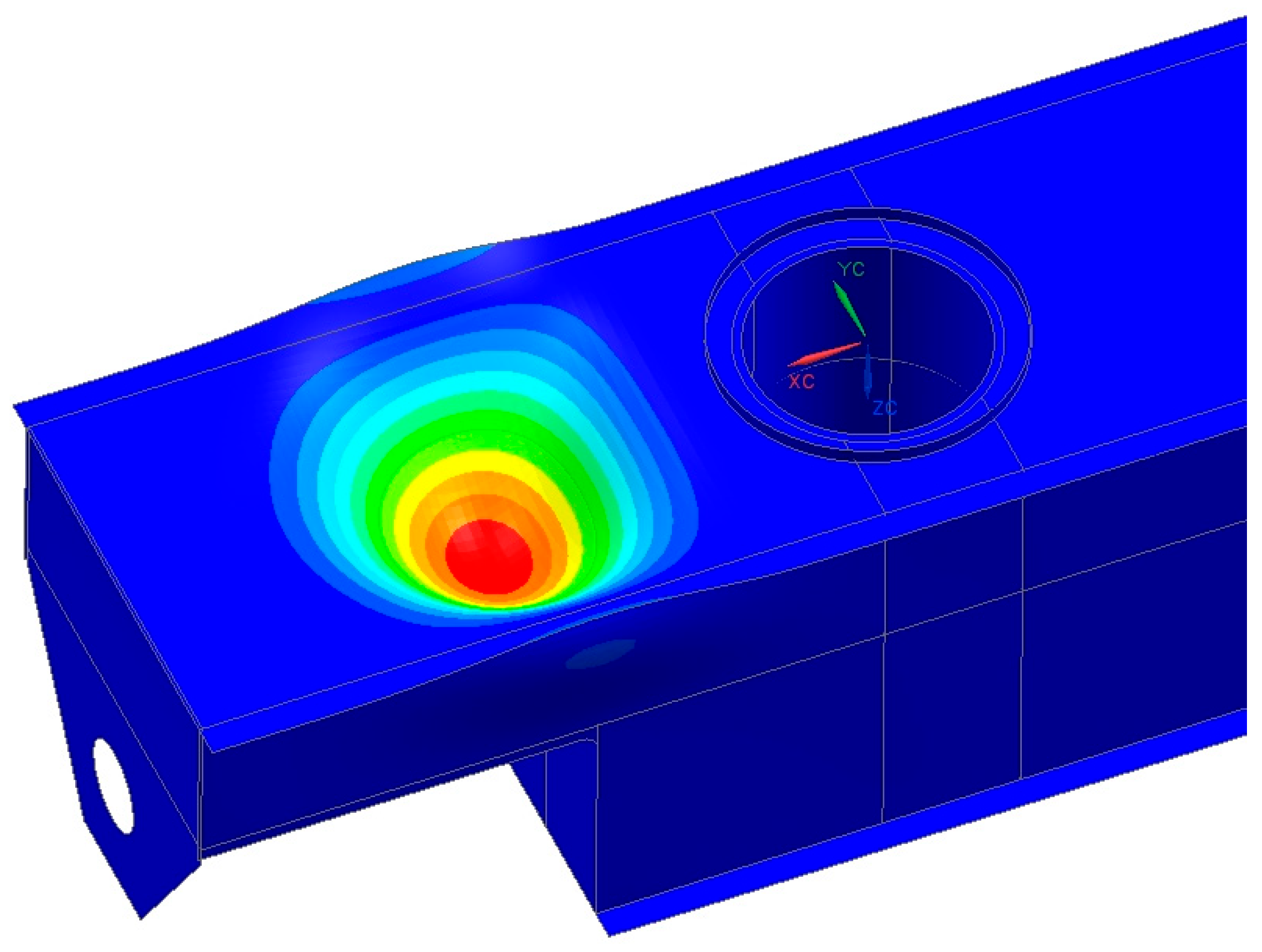

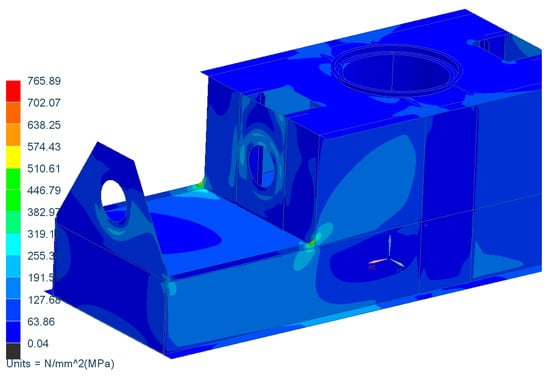

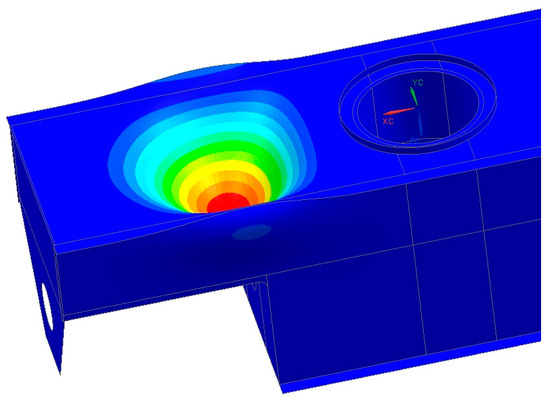

According to the available technical data for the A2RsB-12500 stacker, the total reaction forces acting on the rotating support girder were determined in two selected calculation cases. The first one, designated by the standard as HZS4, concerns the travel of a machine (its independent movement). During the normal operation of the bridge of the spreader, it has three support points. Analyzing them in relation to Figure 3 (looking from the left), we identify the following: on the superstructure, a rotating support girder is used and the end conveyor is supported with plaids. In this case, the rightmost support point from Figure 3 does not exist. The second calculation case concerns the extraordinary material on the conveyor belt, which is marked as HZS6 in the standard. In addition to the self-weight of the analyzed structure, the vertical loads resulting from the reaction forces exerted by the carrying structure of the bridge superstructure were also taken into account; these were HZS4-5 786 469 N and HZS6-4 637 830 N. The difference in the total reaction forces is due to the fact that in the traveling case there is one less support point. Figure 8 and Figure 9 shows the stress plot for the HZS4 case and the buckling shape for the HZS4 case. It should be emphasized that, according to the standard guidelines, the permissible buckling coefficient should be ≥ 1.5. Obtaining a buckling factor of 1 in the calculation means that the object will transfer the assumed load without buckling. Obtaining a value below 1 means that the buckling phenomenon will occur. For example, for a factor of 0.9, this means that 90% of the assumed load in the calculation can be transferred. A similar relationship has been identified for coefficients greater than 1. Obtaining a negative result means that the buckling phenomenon occurs in the opposite direction of action of the loads.

Figure 8.

Equivalent Von Mises stress distribution in MPa—linear material model.

Figure 9.

Buckling shape for factor 1.86 for HZS4 horizontal position.

The FEM analyses of material strength showed one region with a yield strength exceeding that of the original material, assuming that we had a linear model of the material. It did not occur in the area where the failure occurred, nor at any of the critical points of the structure. The machine owner performed his own NDT testing of the identified area, which did not show any cracks in the material. This indicates that the strength of the material has not been exceeded. There was a local phenomenon of strengthening of the material as a result of plastic deformation. The value of the buckling coefficient for the analyzed case was also higher than the standard recommendations; for HZS 4 it was 1.86 and for HZS6 its value was 4.31. According to the available technical and operational documentation of the stacker, it is allowed to operate at an incline. The above analyses carried out do not include inclination. Therefore, additional analyses were performed, taking the slope angle into account. The tilt caused an uneven distribution of the reaction force between the left and right sides. The calculations assumed a slope of 5% (due to travel-HZS4) and 3% (based on work involving the extraordinary excavated material—HZS6). The following reaction forces are assumed according to Table 1.

Table 1.

Calculated reaction forces for individual load cases.

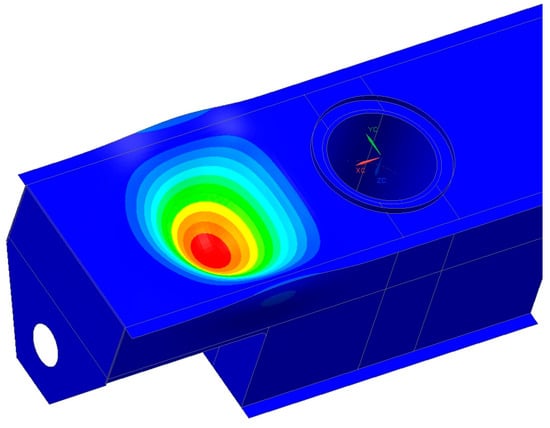

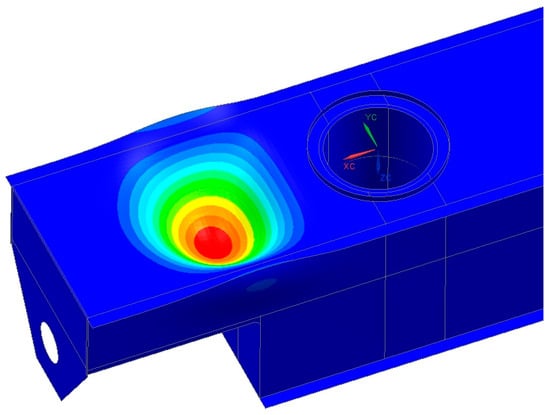

After taking into account the non-uniform distribution of reaction forces according to Table 1, the following results were obtained for the buckling analysis. It turned out that inclination has a significant impact on the recorded values of the buckling coefficients. It is an important component that determines their values. For the case of HZS4 in the incline, the value was 1.51 (Figure 10), and for the case of HZS6 in the slope, the value was 2.59 (Figure 11). These values were significantly lower than those obtained for the horizontal position, which was characterized by an even distribution of reaction forces to the rotating support girder. It should be noted that standards [12,13] do not require designers to calculate machines at the maximum allowable inclinations in the cases analyzed.

Figure 10.

Buckling shape for the factor of 1.51 for HZS4 in inclination.

Figure 11.

Buckling shape for a factor of 2.59 for HZS6 at inclination.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

As the calculations showed, in the cases both with inclination and without inclination, the values of the buckling coefficients significantly differed from each other. In the case analyzed, for HZS4, assuming that the machine traveled, the safety factor was at the limit of an acceptable value. The described machine does not always work on a well-prepared surface, which may cause local exceedances of the acceptable inclination of 5%. Therefore, there is a likelihood that the phenomenon that is presented in Figure 5 will occur. It should also be emphasized that the machine has been in operation for 40 years. Taking into account the time that elapsed from the start of use to the moment of failure, the following recommendations were presented. The first recommended step is to design a new rotating support girder with superior buckling resistance. It is also recommended that the ground be prepared more thoroughly to ensure that the risk of encountering a slope greater than allowed by the standards (5%) can be minimized. It is also suggested that the entire support system be redesigned and replaced with a modernized version. Due to the expected lifetime of operation of the examined technical facility, these measures were considered economically unjustified.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M. and J.W.; methodology, P.M. and J.W.; software, M.O. and J.W.; validation, P.M. and J.W.; formal analysis, J.W.; investigation, P.M. and J.W.; resources, P.M. and J.W.; data curation, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.O. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, P.M., M.O. and J.W.; visualization, M.O. and J.W.; supervision, P.M.; project administration, P.M.; funding acquisition, P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rusiński, E.; Czmochowski, J.; Moczko, P.; Pietrusiak, D. Challenges and strategies of long-life operation and maintenance of technical objects. FME Trans. 2016, 44, 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Dudziński, W.; Odyjas, P.; Olejnik, M.; Moczko, P.; Pietrusiak, D.; Więckowski, J. Root cause analysis and evaluation of corrective actions for discharge boom suspension failure in bucket wheel excavator. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danicic, D.; Sedmak, S.; Ignjatovic, D.; Mitrovic, S. Bucket wheel excavator damage by fatigue fracture—Case study. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2014, 3, 1723–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Papadopoulou, S.; Pressas, I.; Vazdirvanidis, A.; Pantazopoulos, G. Fatigue failure analysis of roll steel pins from a chain assembly: Fracture mechanism and numerical modeling. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 101, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moczko, P.; Pietrusiak, D.; Wieckowski, J. Investigation of the failure of the bucket wheel excavator bridge conveyor. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 106, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsić, M.; Bošnjak, S.; Zrnić, N.; Sedmak, A.; Gnjatović, N. Bucket wheel failure caused by residual stresses in welded joints. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2011, 18, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, A.A.; Venturino, P.; Otegui, J.L. Common root causes in recent failures of cranes. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2014, 39, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulfam, S.; Ahmad, K.; Mian, A.Y.; Ahmad, Z. Analyzing buckling phenomena in an external pressure vessel: Implications for design and safety. Fusion Eng. Des. 2025, 212, 114852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaca, R.C.; Godoy, L.A. Wind buckling of metal tanks during their construction. Thin-Walled Struct. 2010, 48, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugaric, U.; Tanasijevic, M.; Polo Vina, D.; Ignjatovic, D.; Jovancic, P. Lost production costs of the overburden excavation system caused by rubber belt failure. Eksploat. I Niezawodn. -Maint. Reliab. 2012, 14, 333–341. [Google Scholar]

- Mateus, A.F.; Witz, J.A. A parametric study of the post-buckling behaviour of steel plates. Eng. Struct. 2001, 23, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-G-47000-2:2011; Górnictwo Odkrywkowe—Koparki Wielonaczyniowe i Zwałowarki—Część 2: Podstawy Obliczeniowe. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. (In Polish)

- DIN 22261-2:1997; Bagger, Absetzer und Zusatzgeräte in Braunkohlentagebauen—Teil 2: Berechnungsgrundlagen. German Institute for Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 1997. (In German)

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).