Utilisation of Mining Waste †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Creation of the Mining Waste

- Accessibility and feasibility of sample collection with necessary site agreements;

- Inclusion of waste from deep black coal mining only;

- Heap volume exceeding 100,000 m3;

- Status of the heap (active, inactive, or reclaimed);

- Environmental risk assessment based on chemical composition and potential hazards.

2.2. Sampling Strategy and Site Selection

2.3. Sample Preparation

2.4. Gasification Testing

2.4.1. Reactor Description

2.4.2. Test Description

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Selection Criteria and Data for Database Creation

3.2. Results of Gasification

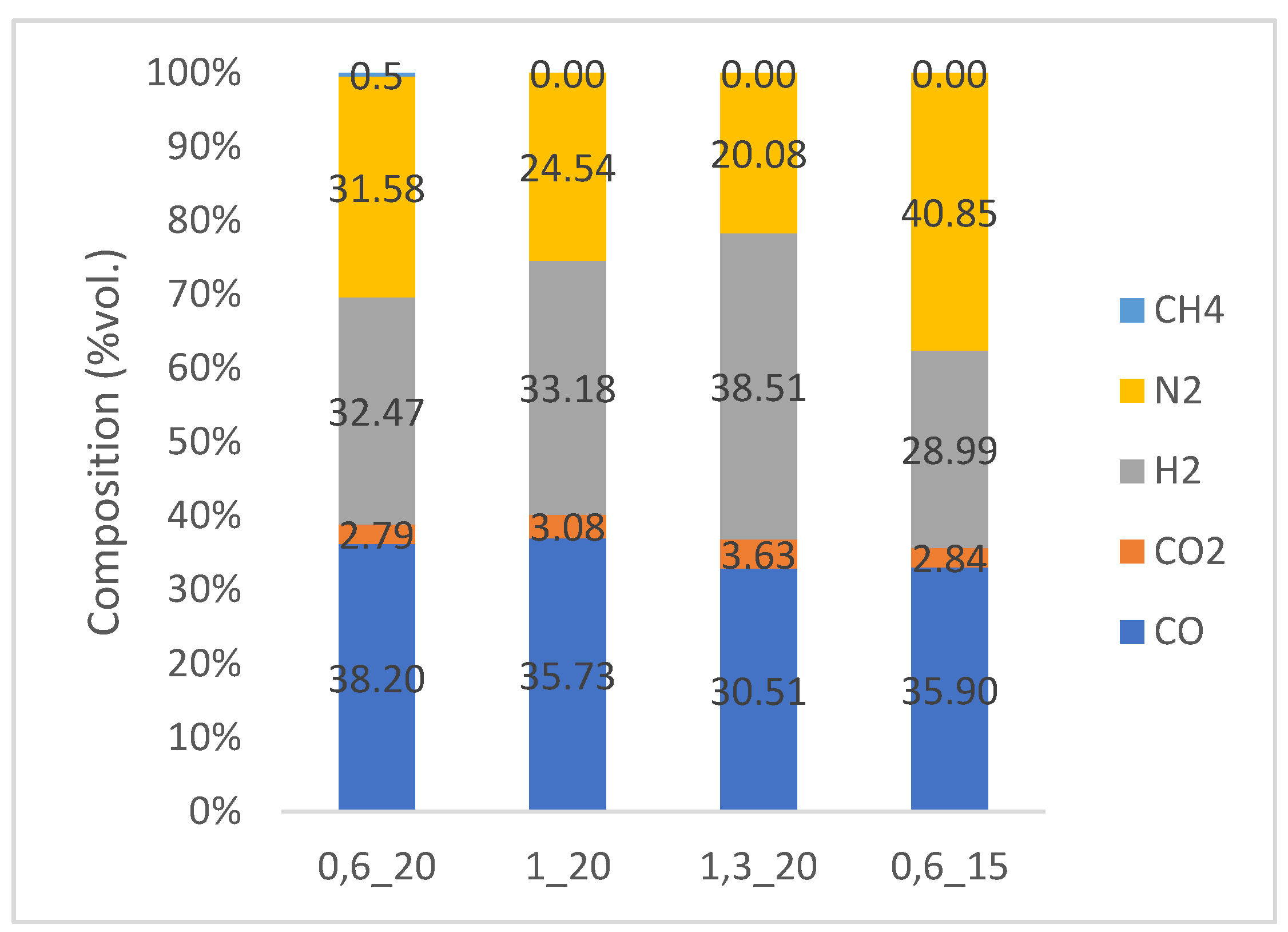

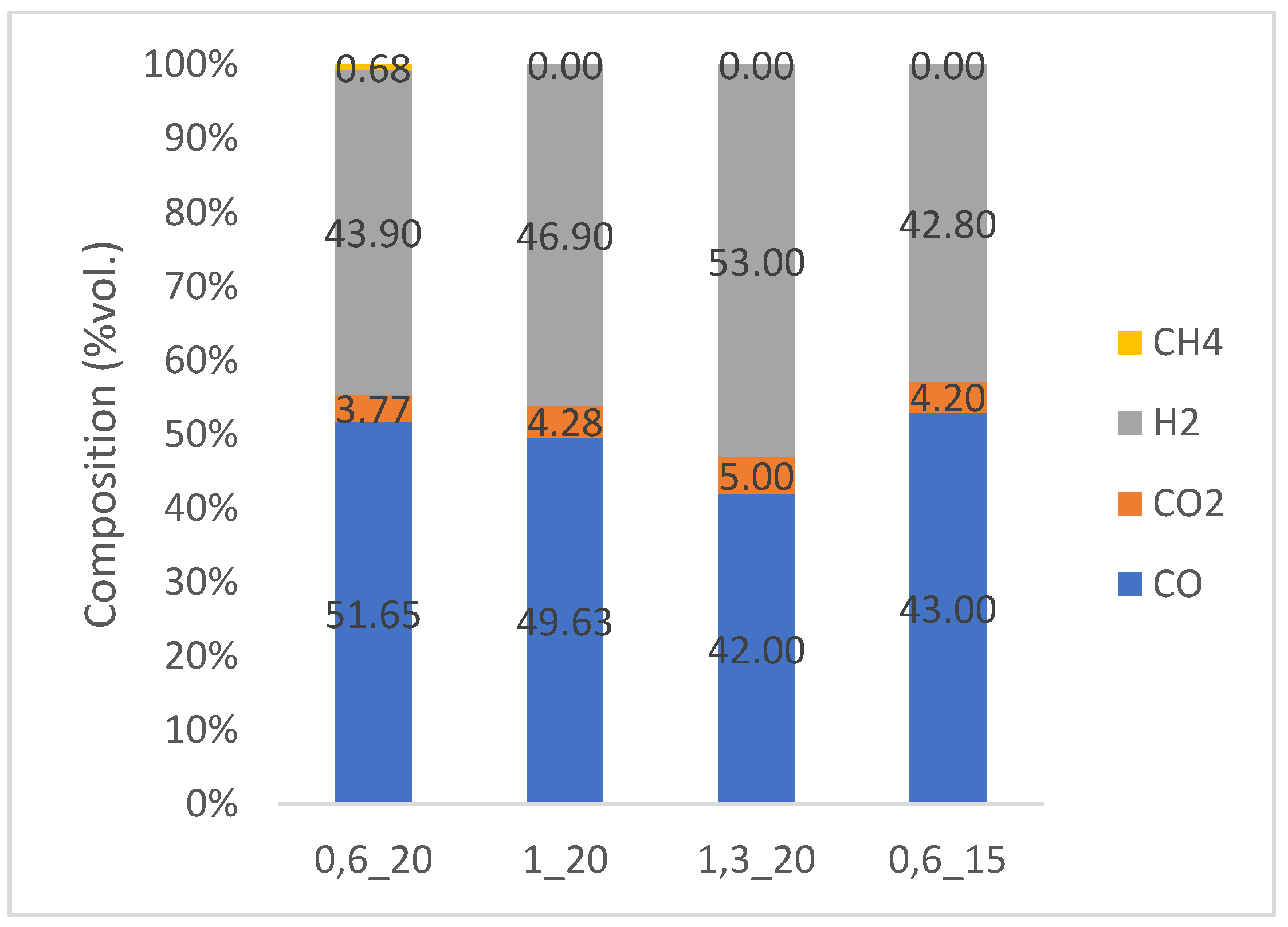

3.2.1. Analysis of Syngas Composition

3.2.2. Mass Balance

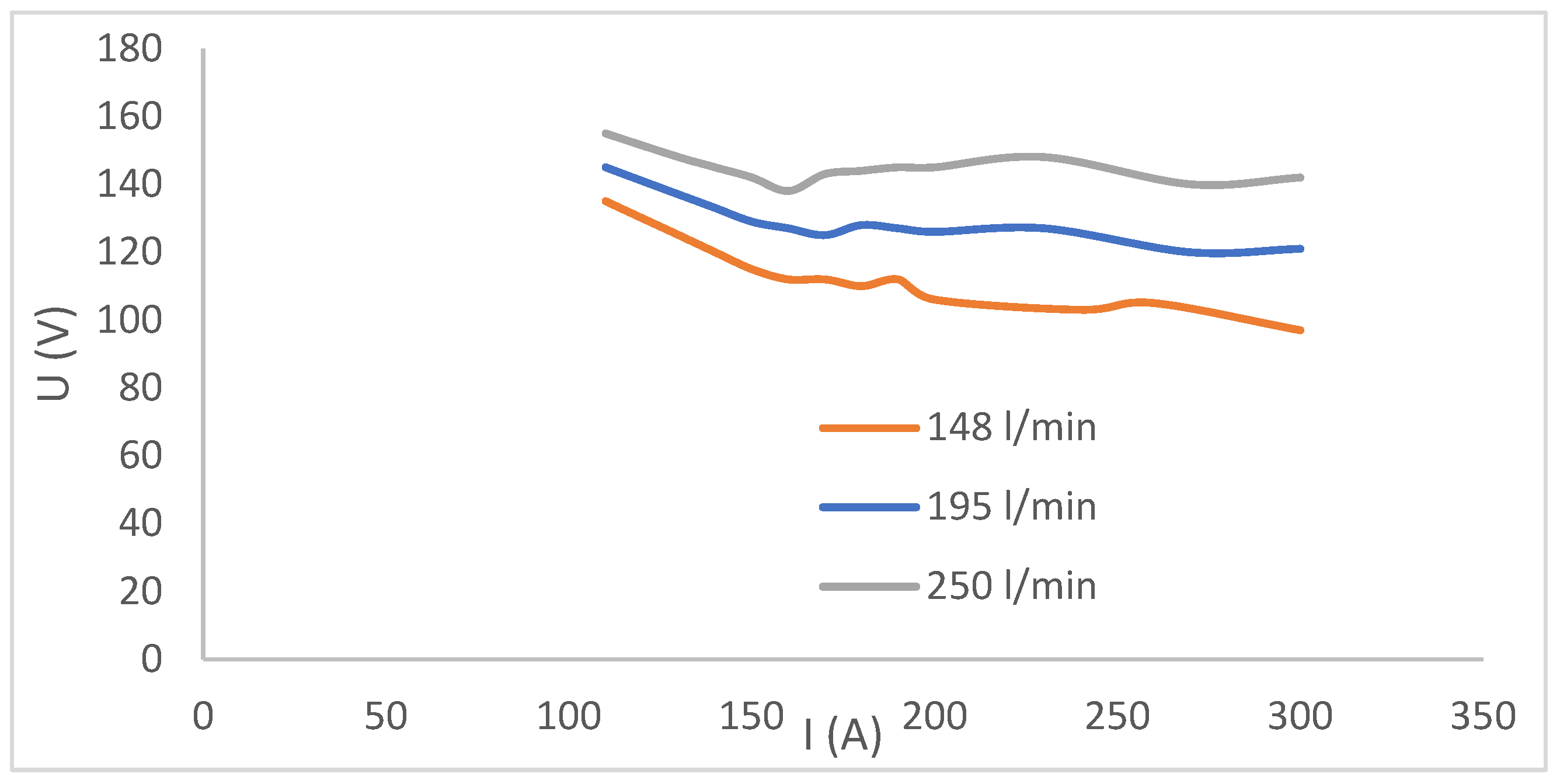

3.2.3. VA Characteristics of Plasma Torch

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balat, M. Coal in the Global Energy Scene. Energy Sources B Econ. Plan. Policy 2009, 5, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, V.; Salieiev, I.; Kovalevska, I.; Chervatiuk, V.; Malashkevych, D.; Shyshov, M.; Chernyak, V. A New Concept for Complex Mining of Mineral Raw Material Resources from DTEK Coal Mines Based on Sustainable Development and ESG Strategy. Mining Miner. Depos. 2023, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosmukhamedov, N.K.; Zholdasbay, E.E.; Egizekov, M.G. New Opportunities for the Development of the Coal Industry: Technology of Waste Gas Purification from SO2, NOx, CO2. Eng. J. Satbayev Univ. 2022, 144, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Coal Mid Year Update—July 2024. Paris, 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/coal-mid-year-update-july-2024 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Ribeiro, J.; Suárez Ruiz, I.; Flores, D. Geochemistry of Self Burning Coal Mining Residues from El Bierzo Coal Field (NW Spain): Environmental Implications. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2016, 159, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babets, Y.K.; Bielov, O.P.; Shustov, O.O.; Barna, T.V.; Adamchuk, A.A. The Development of Technological Solutions on Mining and Processing Brown Coal to Improve Its Quality. Nauk. Visn. Nats. Hirn. Univ. 2019, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chou, C.-L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ge, Y.; Zheng, C. Trace Element Emissions from Spontaneous Combustion of Gob Piles in Coal Mines, Shanxi, China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2008, 73, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haibin, L.; Zhenling, L. Recycling Utilization Patterns of Coal Mining Waste in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šigut, O.; Široký, T.; Janáková, I.; Střelecký, R.; Čablík, V. Assessment of Gravity Deportment of Gold Bearing Ores: Gravity Recoverable Gold Test. Minerals 2024, 14, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Hao, W.; Bian, Z.; Lei, S.; Wang, X.; Sang, S.; Xu, S. Effect of Coal Mining Activities on the Environment of Tetraena mongolica in Wuhai, Inner Mongolia, China—A Geochemical Perspective. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2014, 132, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, V.; Perov, M.; Bilan, T.; Novoseltsev, O.; Zaporozhets, A. Technological State of Coal Mining in Ukraine. In Geomining; Shukurov, A., Vovk, O., Zaporozhets, A., Zuievska, N., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Querol, X.; Izquierdo, M.; Monfort, E.; Álvarez, E.; Font, O.; Moreno, T.; Alastuey, A.; Zhuang, X.; Lu, W.; Wang, Y. Environmental Characterization of Burnt Coal Gangue Banks at Yangquan, Shanxi Province, China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2008, 75, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertile, E.; Surovka, D.; Sarcaková, E.; Bozon, A. Monitoring of Pollutants in an Active Mining Dump Ema, Czech Republic. Inzyn. Miner.-J. Pol. Miner. Eng. Soc. 2017, 1, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertile, E.; Surovka, D.; Božon, A. The Study of Occurrences of Selected PAHs Adsorbed on PM10 Particles in Coal Mine Waste Dumps Hermanice and Hrabuvka (Czech Republic). In Proceedings of the 16th 2016, (SGEM 2016) Energy and Clean Technologies (Extended Scientific Sessions), Vienna, Austria, 2–5 November 2016; STEF92 Technology Ltd.: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2016; pp. 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Pallarés, J.; Herce, C.; Bartolomé, C.; Peña, B. Investigation on Co Firing of Coal Mine Waste Residues in Pulverized Coal Combustion Systems. Energy 2017, 140, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xie, M.; Yu, G.; Ke, C.; Zhao, H. Study on Calcination Catalysis and the Desilication Mechanism for Coal Gangue. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 10318–10325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Guo, S.; Guo, Y. Waste Coal Gasification Fine Slag Disposal Mode via a Promising “Efficient Non Evaporative Dewatering & Mixed Combustion”: A Comprehensive Theoretical Analysis of Energy Recovery and Environmental Benefits. Fuel 2023, 339, 126924. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 17246:2024; Coal and Coke—Proximate Analysis. 3rd ed. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Mapy.cz. Available online: https://mapy.com/en/zakladni?x=18.4679454&y=49.8288349&z=12 (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- ISO 1171:2024; Coal and Coke—Determination of Ash. 5th ed. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- ISO 29541:2025; Coal and Coke—Determination of Total Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen—Instrumental Method. 2nd ed. International Standard: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Han, R.; Guo, X.; Guan, J.; Yao, X.; Hao, Y. Activation Mechanism of Coal Gangue and Its Impact on the Properties of Geopolymers: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yugesh, V.; Ganesh, R.; Kandasamy, R.; Goyal, V.; Meher, K. Influence of the Shroud Gas Injection Configuration on the Characteristics of a DC Non-Transferred Arc Plasma Torch. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2018, 38, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meher, K.; Tirwari, N.; Ghorui, S.; Sahasrabudhe, S.; Das, A. Axial Evolution of Radial Heat Flux Profiles Transmitted by Atmospheric Pressure Nitrogen and Argon Arcs. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2012, 23, 065017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulos, M.; Fauchais, P.; Pfender, E. Handbook of Thermal Plasmas, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kezelis, R.; Grigaitiene, V.; Levinskas, R.; Brinkiene, K. The Employment of a High Density Plasma Jet for the Investigation of Thermal Protection Materials. Phys. Scr. 2014, 2014, 014069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Jan Karel (Karviná) | Paskov D | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximate analysis (dry basis) | |||

| Moisture (as received) | 1.06 | 1.23 | wt% |

| Volatile matter | 20.10 | 19.4 | wt% |

| Fixed carbon | 75.4 | 72.9 | wt% |

| Ash | 21.8 | 24.0 | wt% |

| Ultimate analysis (dry, ash-free basis) | |||

| Carbon (C) | 66.12 | 62.74 | wt% |

| Hydrogen (H) | 3.47 | 3.59 | wt% |

| Nitrogen (N) | 0.94 | 0.92 | wt% |

| Sulfur (S) | 0.56 | 0.6 | wt% |

| Oxygen (O) | 4.4 | 4.5 | wt% |

| Calorific value | |||

| Higher heating value (HHV) | 27.9 | 25.3 | MJ/kg |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Janáková, I.; Drabinová, S.; Kielar, J.; Šigut, O.; Heviánková, S. Utilisation of Mining Waste. Eng. Proc. 2025, 116, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116035

Janáková I, Drabinová S, Kielar J, Šigut O, Heviánková S. Utilisation of Mining Waste. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 116(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116035

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanáková, Iva, Silvie Drabinová, Jan Kielar, Oldřich Šigut, and Silvie Heviánková. 2025. "Utilisation of Mining Waste" Engineering Proceedings 116, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116035

APA StyleJanáková, I., Drabinová, S., Kielar, J., Šigut, O., & Heviánková, S. (2025). Utilisation of Mining Waste. Engineering Proceedings, 116(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116035