Abstract

The utilization of waste biomass such as chicken manure (CM) for producing valuable products like fermentable sugars has gained increasing research attention. However, limited studies have explored the effect of acid pretreatment on sugar recovery efficiency specifically from CM. This study investigates the production of glucose and xylose from CM using dilute sulfuric acid (H2SO4) at concentrations of 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 M under varying conditions. The results indicate that the highest yields were achieved from decrystallized CM, producing 46.21 mg glucose/g CM and 8.47 mg xylose/g CM under optimal conditions of 0.6 M H2SO4 and 100 °C. In contrast, non-decrystallized CM yielded 13.98 mg glucose/g CM and 1.67 mg xylose/g CM under 1.0 M H2SO4 and 100 °C. The decrystallization process using concentrated sulfuric acid effectively disrupted the lignin structure and partially hydrolyzed hemicellulose, enhancing cellulose accessibility during subsequent dilute acid hydrolysis. The study also revealed that glucose and xylose yields decreased as the dilute acid concentration increased from 0.6 to 0.8 M and temperature rose from 80 to 100 °C for decrystallized CM. Conversely, for non-decrystallized CM, sugar yields increased with higher acid concentration and temperature. These findings highlight the critical role of pretreatment in improving sugar recovery from CM and suggest that optimizing acid concentration and thermal conditions can enhance the efficiency of biomass conversion. This research contributes to the sustainable valorization of agricultural waste into bio-based products.

1. Introduction

The quick growth of the world population and fast expansion of economies has led to an increasing energy demand. These challenges are the driving force for the researchers to conduct a study to look for feasible alternative fuels. The poultry industry is one of the successful businesses in the Philippines. The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) reported that as of September 2023, the total chicken inventory reached 202.82 million birds; a 1.1% increase compared to the same period in the previous year [1]. Despite the challenges brought to chickens by the hot weather, the PSA reported that there was an increase of about 7.67% in chicken production in the first quarter of 2023. The rise in production resulted in a lower farm gate price of chicken meat in the same year up to 2024 [2]. The increase in the chicken population and production is expected to continue up to 2040 according to the Philippine Poultry Boiler Industry Roadmap 2022–2040 [3].

The continuous growth of large poultry industries leads to the large production of waste such as animal litter, wastewater, and animal manure, with the latter accounting for 50% of the total waste. Chicken manure is rich in nutrients such as nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus, making it a good fertilization material. However, only about 20% of animal manure is sold as organic fertilizer, because excess usage of fertilizer on land results in serious problems such as the eutrophication of water and contamination of groundwater [4]. The rest of chicken manure is then disposed of in landfills, which leads to problems such as bad odor, land space wastage, contamination of groundwater, and the production of ammonia and methane gas. Chicken manure also contains heavy metals such as arsenic, zinc, iron, copper, and manganese [4]. One waste management approach to reducing the problems caused by disposing of chicken manure is to use it as biofuel [5]. One of its currently widespread uses is as biogas [6]. Since animal manure contains carbohydrates, chicken manure has potential as a feedstock for bioethanol production.

Many studies were conducted on the conversion of chicken manure into biogas as an alternative source of energy. It also shows different advantages of biogas production using chicken manure as a feedstock such as low cost of maintenance and ease of operation. However, there are disadvantages such as long residence time, production of inhibitors, and also production of secondary waste such as wastewater [7]. Bioethanol production may pose advantages over biogas production in terms of the following: (1) calorific value, (2) market value, and (3) time of production [8,9,10]. Converting chicken manure into bioethanol is therefore explored in this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Sulfuric acid was purchased from AI MED Laboratory Supplies with a purity of 95%. Ethanol (98% purity), glacial acetic acid (99% purity), and hydrochloric acid (98% purity) were procured from the Adamson University Chemical Engineering Laboratory, Manila, Philippines. Phloroglucinol (99% purity) was procured from the Adamson University Chemistry Laboratory. Deionized water was produced from a Mixed Bed Deionizer Standard Model (On The Go® Portable Water Softeners, LLC, Bloomington, IN, USA).

2.2. Sample Preparations

Fresh chicken manure was obtained from Pecaso Farm in Bicol Province. The sample was placed in an air-tight polyethylene bag. It was placed in an insulated container together with ice to prevent contamination. Two (2) kilograms of raw manure were sun-dried for 48 h and underwent size reduction using a Nutriblitzer (John Mills Limited, Shanghai, China). Afterwards, the sample was screened using a Sieve Shaker and particles passing through Mesh 20 were used for the experiment.

2.3. Physical Pre-Treatment

Fifty-four test tubes were prepared and seven (7) grams of ground manure were mixed with 3.5 mL of deionized water with 2:1 solid (g) to liquid (mL) ratio in each tube. Each test tube underwent centrifugation at 4700 rpm for 5 min to make sure that most of the soluble nitrogen was isolated. Then, water was removed from the sample through decantation. Afterwards, the residue was washed three times with 3.5 mL of deionized water. Samples were sun-dried for 48 h. The samples were refrigerated at 4 °C and will be used in the succeeding steps.

2.4. Acid Decrystallization

Of the 54 samples, 27 samples underwent acid decrystallization. Three (3) grams of pre-treated manure was placed in a 125 mL Erlenmeyer flask. At a solid to liquid ratio of 3:5 by weight loading, approximately 5 g of 75% (wt/wt) sulfuric acid was added to each flask. The flasks were placed in a water shaker bath at 30 °C for 30 min. Afterwards, the samples were immediately subjected to dilute acid hydrolysis.

2.5. Dilute Acid Hydrolysis

All samples were subjected to dilute sulfuric acid hydrolysis. Acid concentrations of 0.6 M, 0.8 M, and 1.0 M were added to the samples that did not undergo acid decrystallization while samples that did undergo acid decrystallization were diluted with deionized water to the desired concentrations. Then, the flasks were placed in an oil bath at a stable temperature (60 °C, 80 °C, and 100 °C) for 30 min. Afterwards, the flasks were removed and cooled to room temperature. The mixtures were filtered. Then, the filtrates were refrigerated at 4 °C and will be used for monomeric sugar analysis.

2.6. Glucose and Xylose Analysis

The produced monomeric sugar extracts were analyzed using a UV–Visible Spectrophotometer (Lambda 25 Series, Perkin Elmer, Inc., Boston, MA, USA). Phloroglucinol was used as a coloring agent. The reagent was prepared by dissolving 2 g of Phloroglucinol in 110 mL of glacial acetic acid, followed by adding 10 mL of anhydrous alcohol and 2 mL of hydrochloric acid. A total of 1 mL of the sample was mixed with 10 mL of the coloring reagent in a 30 mL test tube. The test tubes were subjected to a water bath at approximately 100 °C. Afterwards, samples were cooled before analysis. The spectral scanning was set between wavelengths of 350 and 600 nm [11].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Yield of Glucose and Xylose from Chicken Manure

The production of glucose and xylose from chicken manure required proper chemical treatment and operating conditions to maximize the yield of glucose and xylose. For this research, three factors were considered: acid decrystallization, dilute acid concentration, and temperature. The results are shown in Table 1. Table 1 shows the average yield of glucose and xylose produced from chicken manure. The maximum average yield of glucose of 46.21 mg glucose/g chicken manure was achieved when subjected to acid decrystallization using 75% (w/w) sulfuric acid.

Table 1.

The average yield of glucose and xylose from chicken manure.

It was obtained with a dilute acid concentration of 0.6 M and a temperature of 100 °C at a constant reaction time of 30 min. On the other hand, the maximum yield of xylose of 8.47 mg xylose/g chicken manure was achieved when subjected to acid decrystallization using 75% (w/w) sulfuric acid. It was obtained with a dilute acid concentration of 0.6 M and a temperature of 100 °C at a constant reaction time of 30 min. For the non-decrystallized chicken manure, the maximum yields of glucose and xylose were 13.98 mg glucose/g chicken manure and 1.67 mg xylose/g chicken manure, respectively. Both results were obtained when dried chicken manure underwent dilute acid hydrolysis without being subjected to acid decrystallization, with an acid concentration of 1.0 M at the temperature of 100 °C at a constant reaction time of 30 min. The study conducted by Woldesenbet et al. [12] stated that the maximum yield of glucose was obtained from the hydrolysis of chicken manure at 0.8 M sulfuric acid and a temperature of 100 °C for 30 min of reaction time. The difference is due to the chicken manure characteristics, which reflect the food they intake and their origin [13].

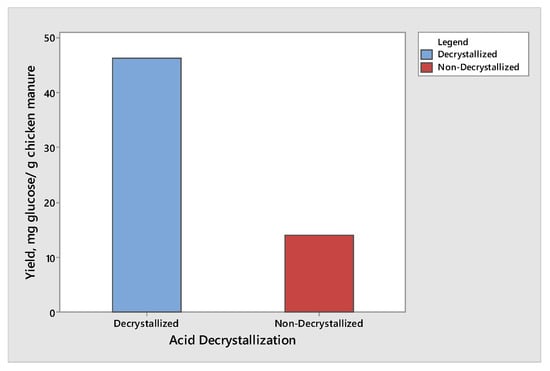

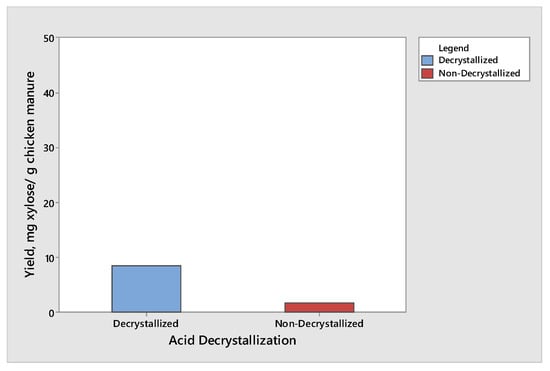

3.2. The Effect of Acid Decrystallization

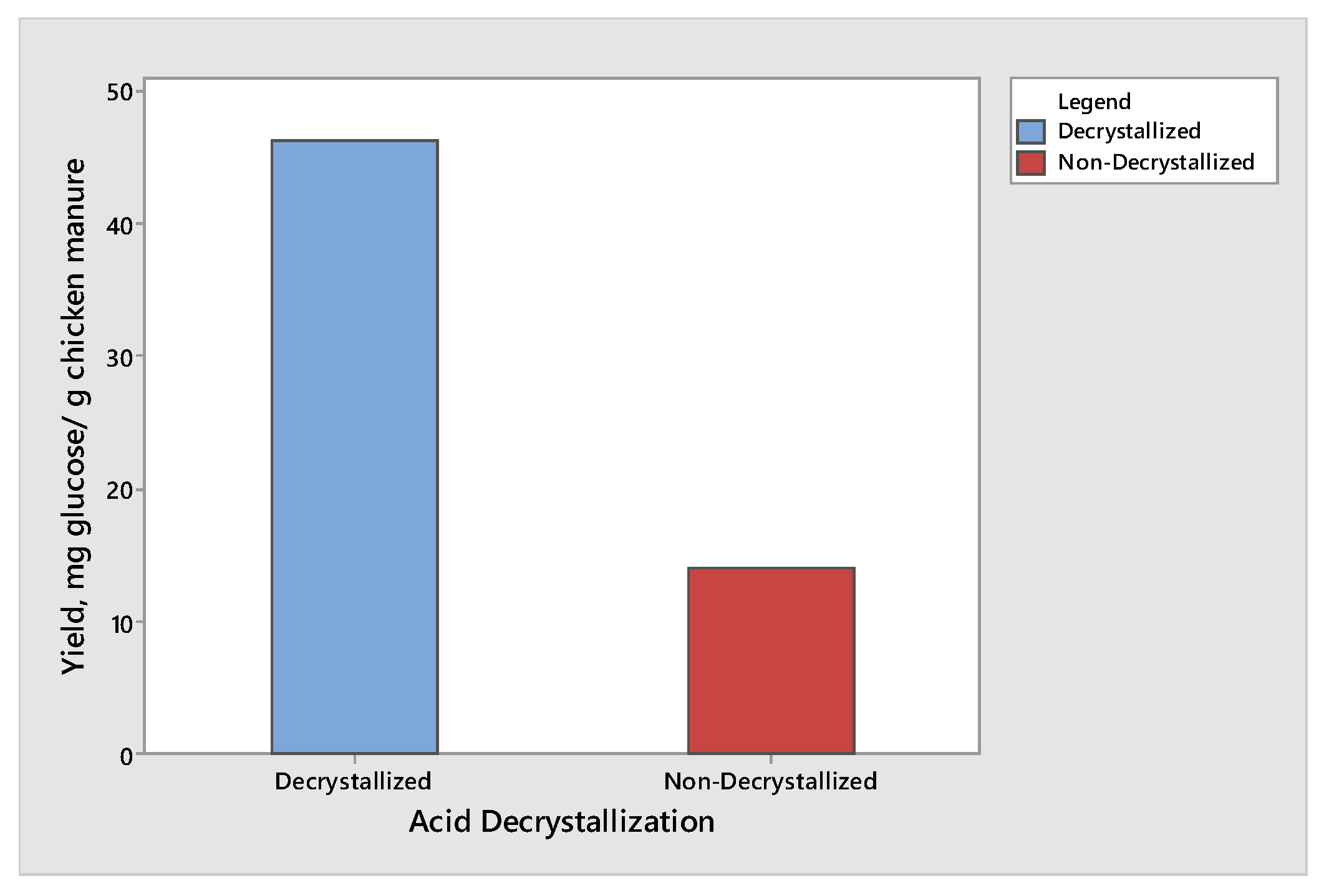

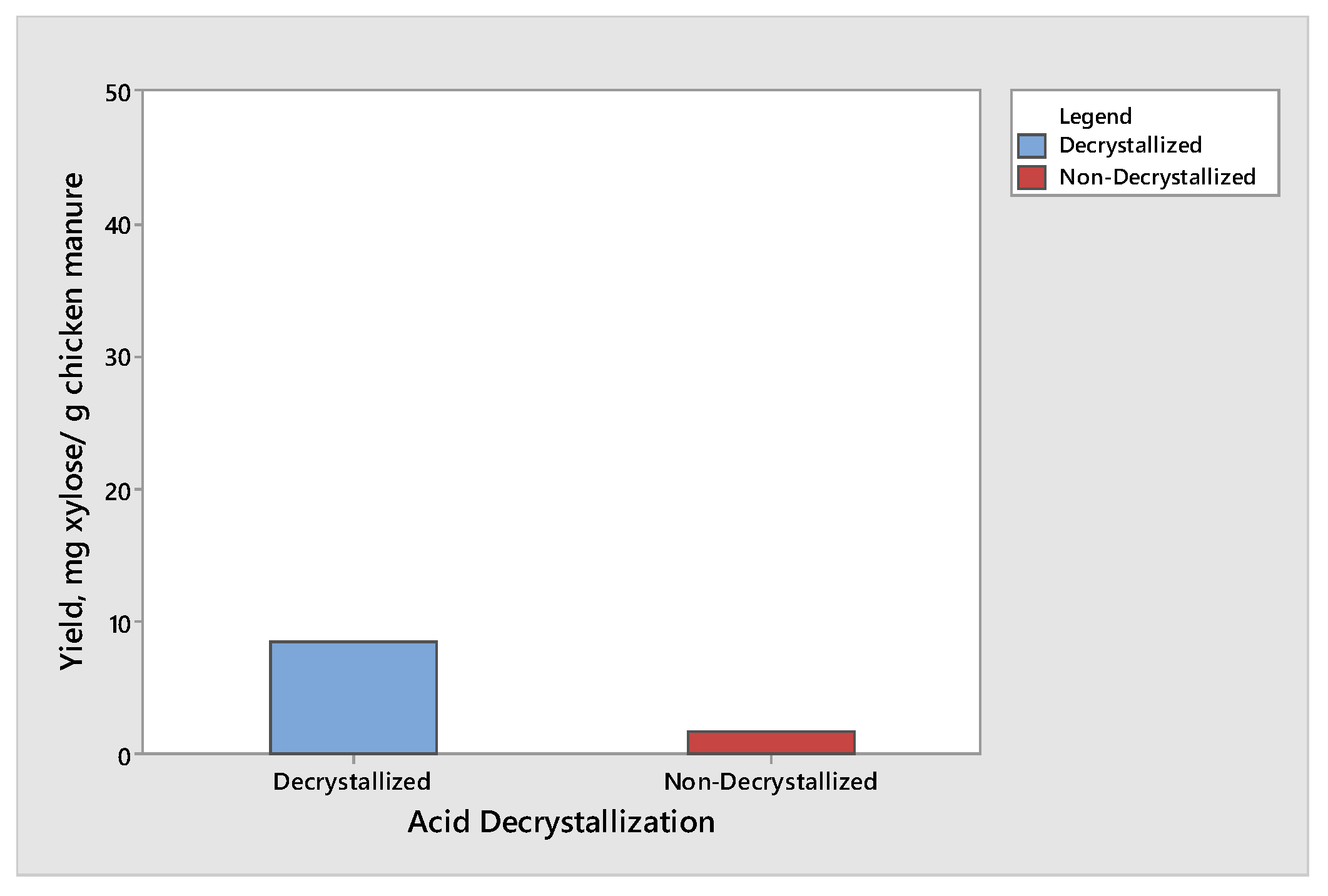

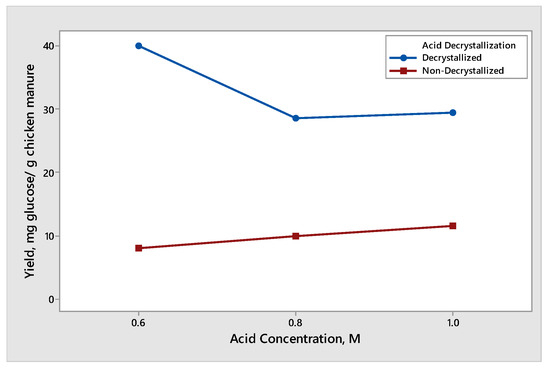

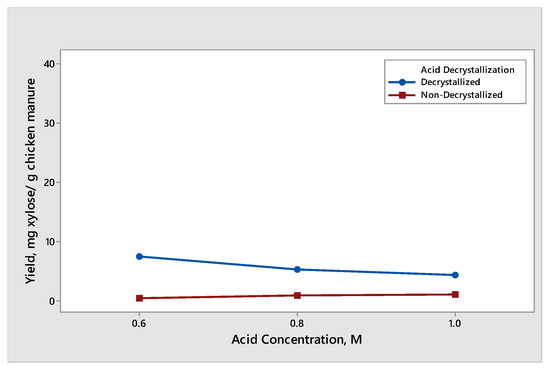

The effect of acid decrystallization on the production of glucose and xylose from chicken manure was observed by subjecting half of the samples to the acid decrystallization before dilute acid hydrolysis, while the remaining half of the samples were subjected to dilute acid hydrolysis without subjecting to acid decrystallization. The results showed that the chicken manure produced the highest yield of glucose and xylose when subjected to acid decrystallization before dilute acid hydrolysis. This is due to the 75% (w/w) sulfuric acid breaking the structure of the lignin and partially hydrolyzing the hemicellulose, making cellulose more accessible before dilute acid hydrolysis. The results for glucose and xylose are given in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. The results shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2 produced the same trend. The maximum yield of glucose was 46.21 mg glucose/g chicken manure, while the maximum yield of xylose was 8.47 mg xylose/g chicken manure. Both results were obtained from decrystallized chicken manure. On the other hand, the maximum yield of glucose and xylose under non-decrystallized chicken manure were 13.98 mg glucose/g chicken manure and 1.67 mg xylose/g chicken manure, respectively. Based on the results gathered, there was a decrease of 69.74% and 80.28% in the yield in glucose and xylose, respectively, if the samples did not undergo acid decrystallization. The results agreed with the study conducted by Wijaya et al. [14] who compared the two-step concentrated acid hydrolysis process for the extraction of sugars from lignocellulosic biomass. It shows that acid decrystallization plays an important role in the hydrolysis of cellulose and hemicellulose. This indicates that the concentrated acid effectively dismantles the lignocellulosic structure and increases the porosity of lignocellulosic materials. It indicates that the fast degradation of cellulose is achieved under acid decrystallization. The cellulose in the biomass became more accessible before acid hydrolysis [15,16].

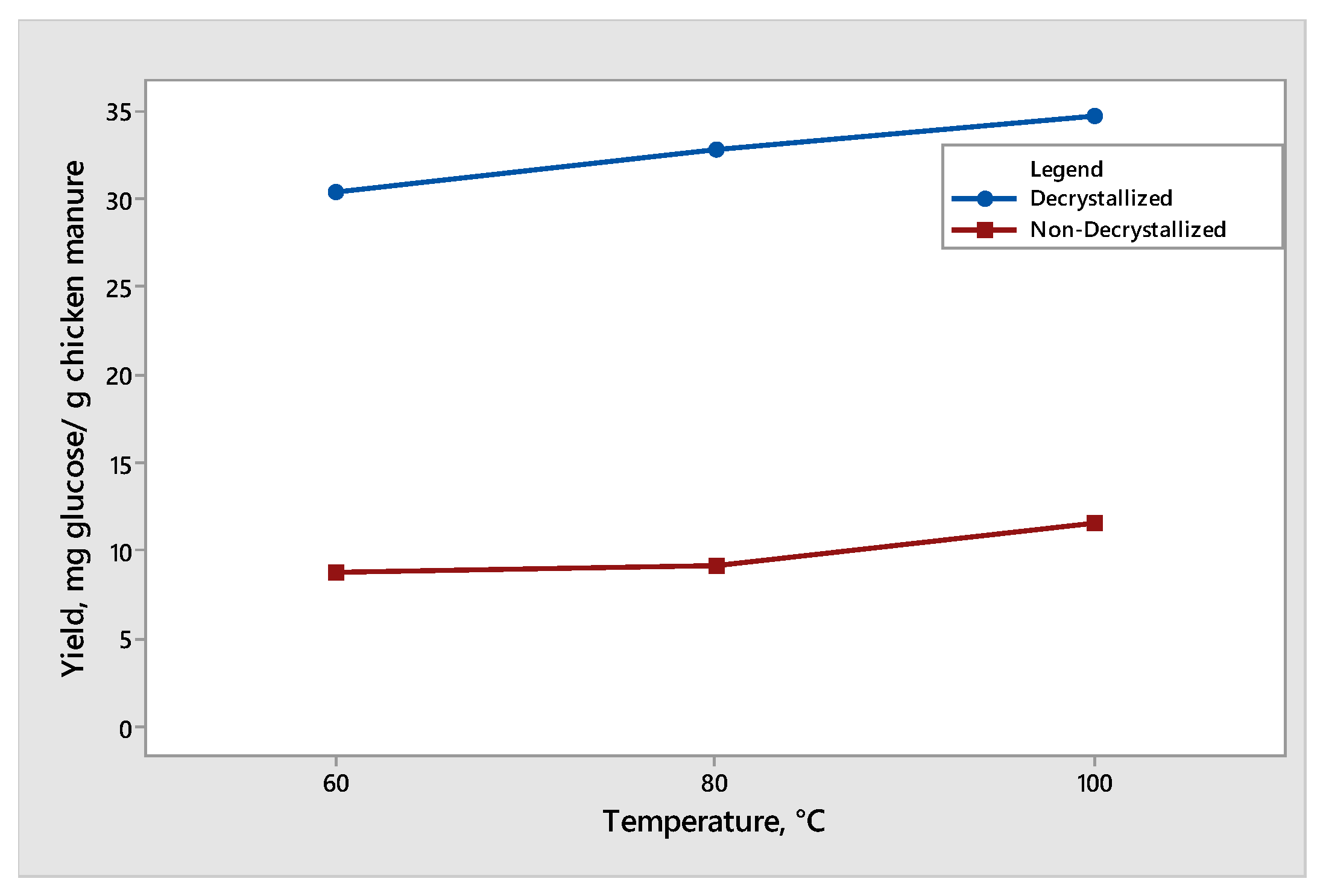

Figure 1.

Yield of glucose produced from decrystallized and non-decrystallized chicken manure.

Figure 2.

Yield of xylose produced from decrystallized and non-decrystallized chicken manure.

3.3. The Effect of Dilute Acid Concentration

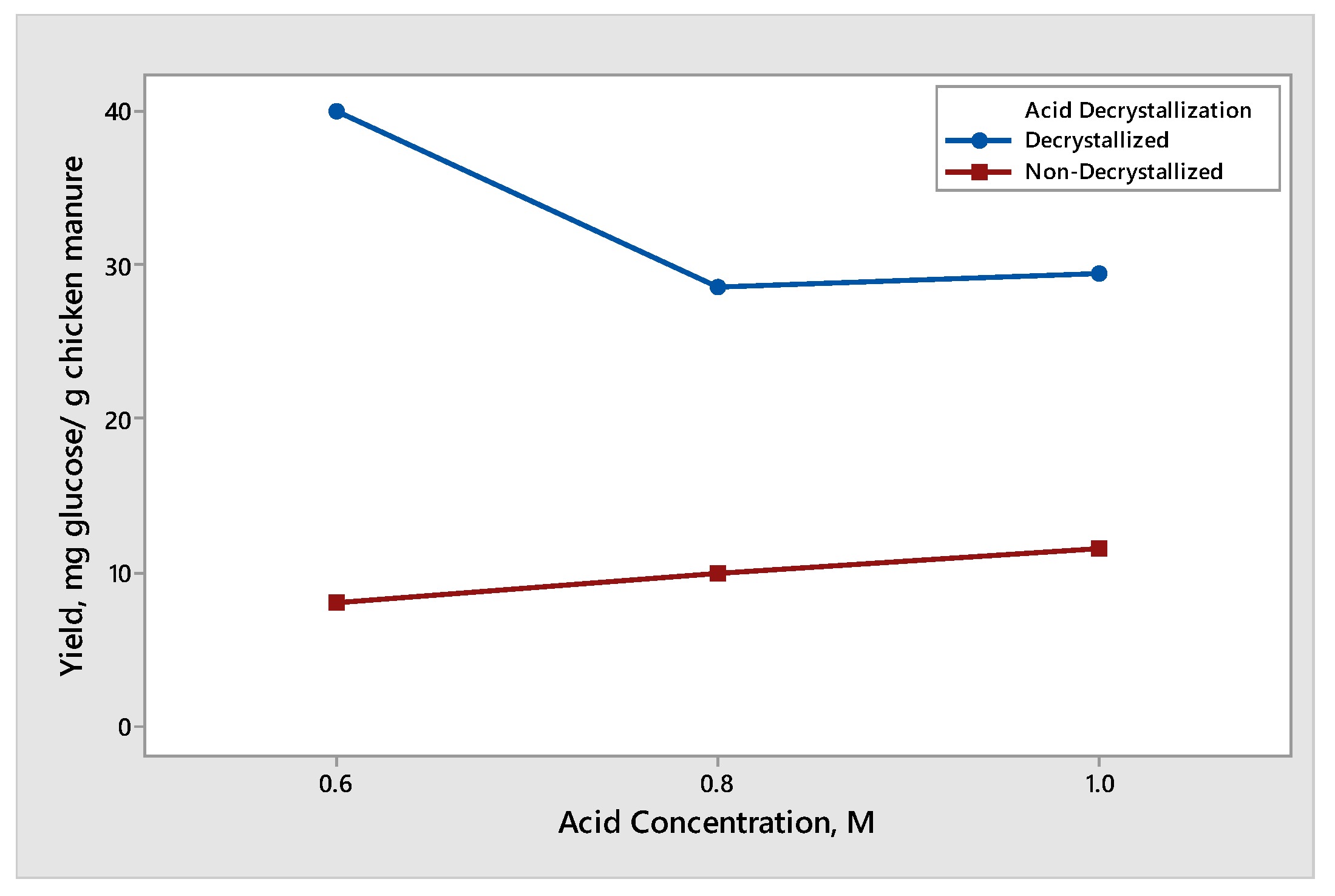

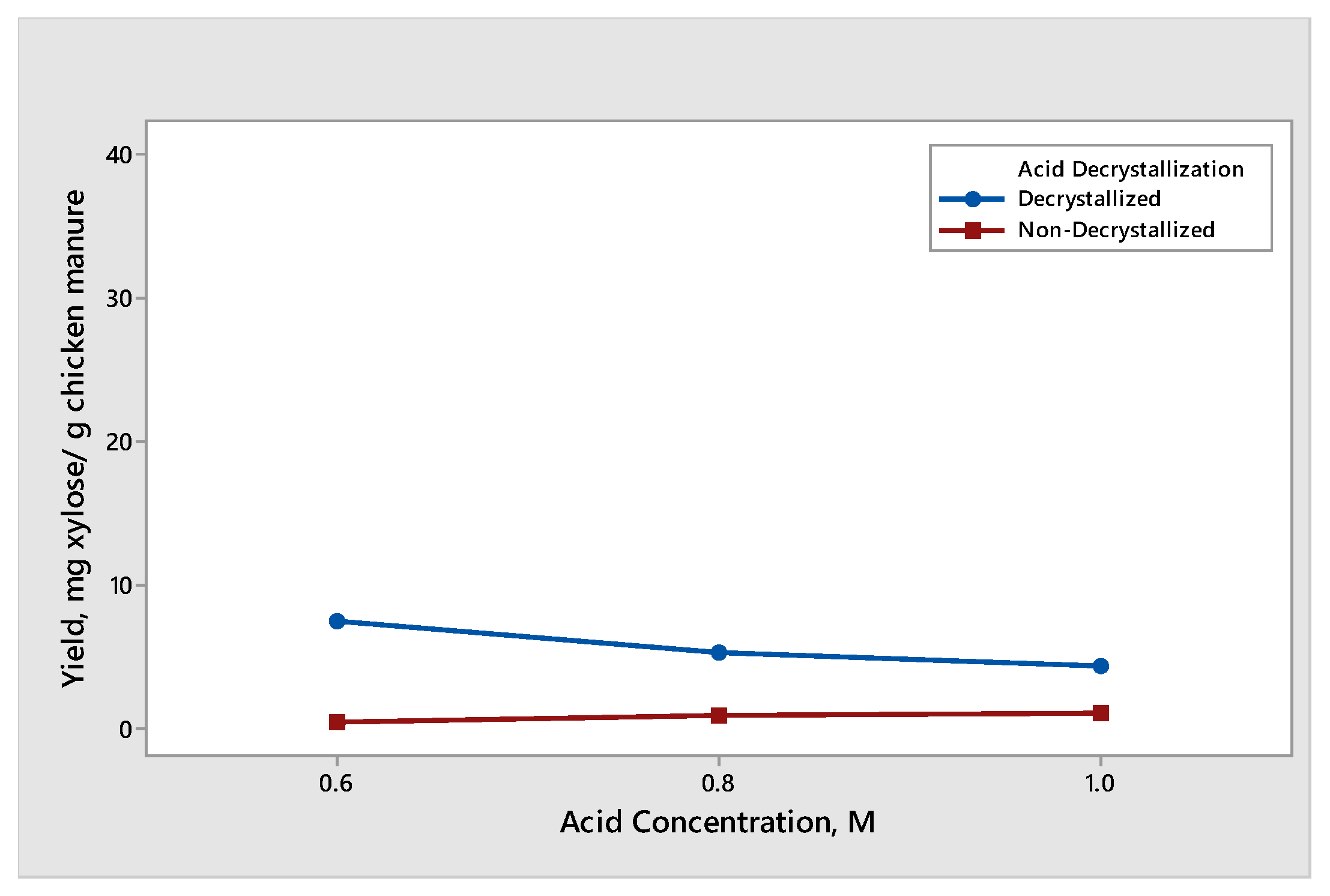

The effect of acid concentration was observed when decrystallized chicken manure samples and non-decrystallized chicken manure were subjected to dilute acid hydrolysis with an acid concentration of 0.6 M, 0.8 M, and 1.0 M. The results for the yield of glucose and xylose produced different trends and are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively. The effect of dilute acid concentration on the production of glucose from decrystallized and non-decrystallized chicken manure is shown in Figure 3. The maximum average yield of glucose was 39.93 mg glucose/g chicken manure. It was obtained from decrystallized chicken manure under the condition of 0.6 M sulfuric acid. On the other hand, the maximum average yield of glucose from non-decrystallized chicken manure was 11.54 mg glucose/g chicken manure under the condition of 1.0 M. The result shown in Figure 3 under non-decrystallized chicken manure indicates that as we increased the acid concentration, the yield on the glucose production was also increasing. This is due to the lignin structure being delignified at a slower rate compared to decrystallized chicken manure. For this reason, it is difficult to hydrolyze the hemicellulose and cellulose that are trapped under the lignin structure. On the other hand, the result shown in Figure 3 under decrystallized chicken manure indicates that as we increased the acid concentration from 0.6 M to 0.8 M, the average yield for glucose decreased. The decrease in the yield of glucose from 0.6 M to 0.8 M is due to the conversion of glucose into inhibitors such as furfural derivatives. However, as we increased the concentration from 0.8 M to 1.0 M, the average yield for glucose also increased. The results gathered agreed with the study conducted by Woldesenbet et al. [12], wherein the glucose yield decreased as they increased the acid concentration from 0.6 M to 0.8 M. On the other hand, increasing the acid concentration from 0.8 M to 1.0 M causes the glucose yield to increase. The effect of dilute acid concentration on the production of xylose from decrystallized and non-decrystallized chicken manure is shown in Figure 4. The maximum average yield of xylose was 7.37 mg xylose/g chicken manure. It was obtained from decrystallized chicken manure under the condition of 0.6 M sulfuric acid. On the other hand, the maximum average yield of xylose from non-decrystallized chicken manure was 0.94 mg xylose/g chicken manure under the condition of 1.0 M. The result shown in Figure 4 under decrystallized chicken manure indicates that xylose was degrading into inhibitors such as furfural derivatives as we increased the concentration. It shows that as we increased the acid concentration, the yield in xylose started to decrease. The results also agreed with the study conducted by Wijaya et al. [14], where the glucose/xylose ratio started to increase, indicating that the xylose started to degrade and was converted to furfural derivatives as we increased the acid concentration.

Figure 3.

Yield of glucose produced from decrystallized and non-decrystallized chicken manure under different acid concentration controls (0.6 M, 0.8 M, and 1.0 M).

Figure 4.

Yield of xylose produced from decrystallized and non-decrystallized chicken manure under different acid concentration controls (0.6 M, 0.8 M, and 1.0 M).

It is due to this that xylose formed before glucose. This was caused by partially hydrolyzed hemicellulose while dried chicken manure was subjected to acid decrystallization, resulting in the formation of xylose and a small amount of glucose. On the other hand, the result shown in Figure 4 for non-decrystallized chicken manure indicates that as we increased the acid concentration, the formation of xylose started to increase. This is due to the lignin structure being delignified at a slower rate at a dilute acid concentration.

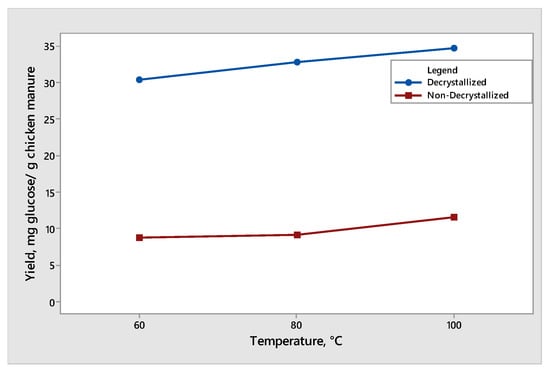

3.4. The Effect of Temperature

The effect of temperature was observed when decrystallized chicken manure and non-decrystallized chicken manure were subjected to dilute acid hydrolysis at three controlled temperatures (60 °C, 80 °C, and 100 °C). The results of the effect of the temperature on glucose and xylose are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively. The maximum mean of glucose produced was 34.68 mg glucose/g chicken manure under decrystallized chicken manure at 100 °C at a constant reaction time of 30 min. On the other hand, under the non-decrystallized chicken manure, the maximum mean of glucose produced was 11.54 mg glucose/g chicken manure at 100 °C at a constant reaction time of 30 min. Based on Figure 5, at a reaction time of 30 min, the increase in temperature from 60 °C to 80 °C and 100 °C showed an increase in the glucose yield from 30.39 to 32.80 and 34.68 mg glucose/g chicken manure for decrystallized chicken manure, respectively. The change in the results observed from 80 °C to 100 °C is noticeably higher relative to the change from 60 °C to 80 °C. For non-decrystallized chicken manure, at a reaction time of 30 min, the increase in temperature from 60 °C to 80 °C and 100 °C showed an increase in the glucose yield. As the temperature increased, the glucose produced also increased. The results and trend agreed with the study of Liao et al. (2006) [17]. As they increased the temperature at 30 min reaction time, the glucose yield started to increase. The results showed that changing the temperature positively affects the hydrolysis of cellulose and hemicellulose, which was demonstrated by the increasing generation rate of glucose when elevating the temperature. This was due to the breakage of glucose linking bonds on crystalline cellulose and hemicellulose. Also, the linking bonds between glucose in the crystalline structure of cellulose have a greater bond strength, which require high temperatures to cut the linking bonds between glucose [18].

Figure 5.

Yield of glucose produced from decrystallized and non-decrystallized chicken manure under different temperature (60 °C, 80 °C, and 100 °C).

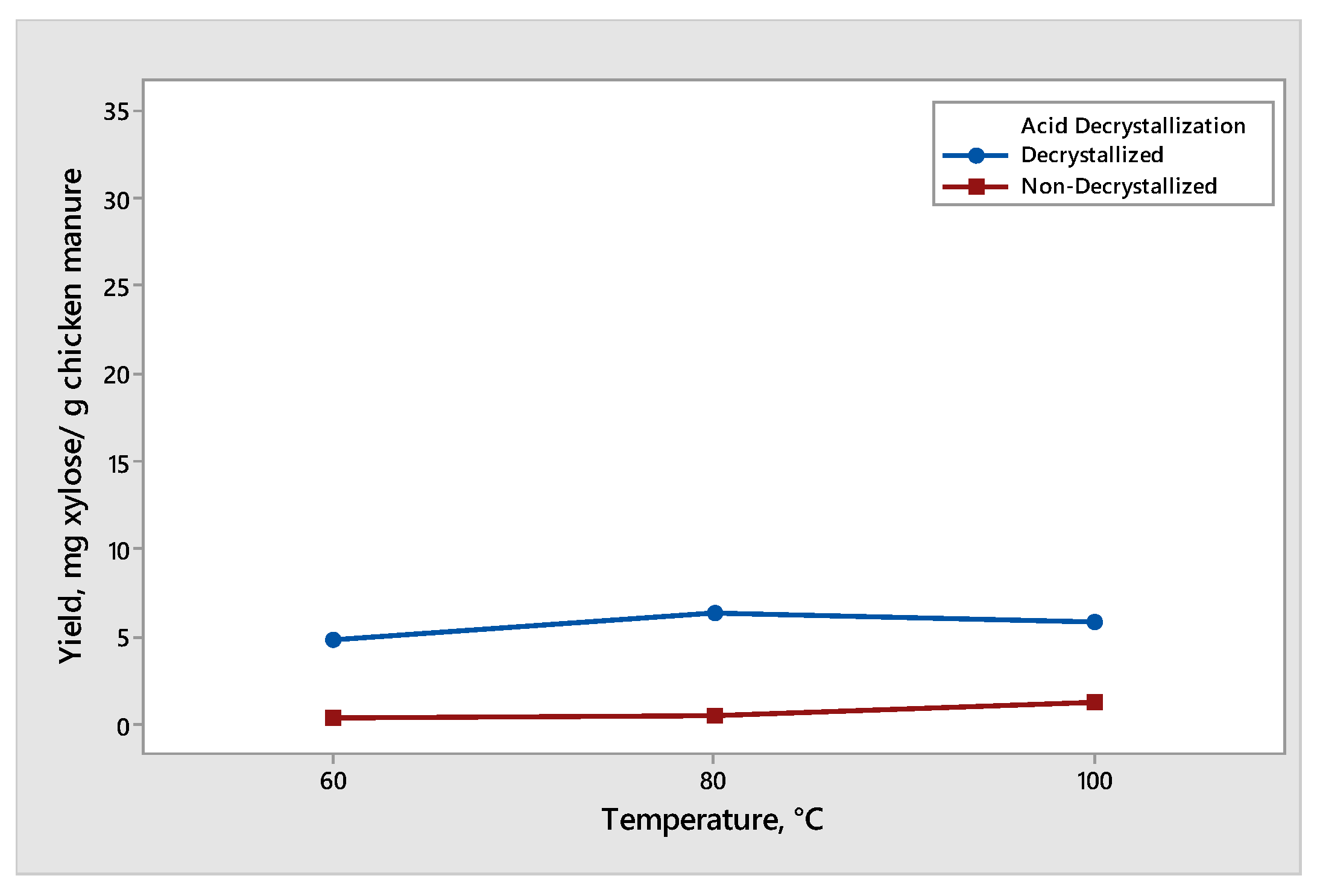

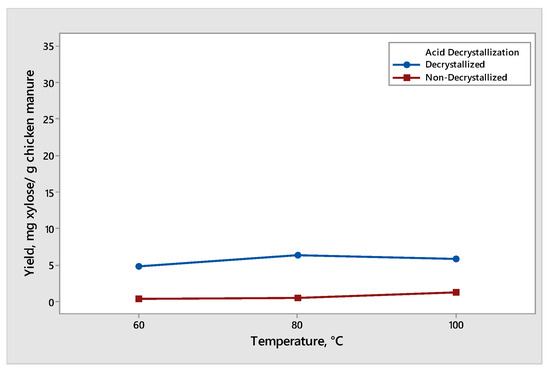

Figure 6.

Yield of xylose produced from decrystallized and non-decrystallized chicken manure under different temperature (60 °C, 80 °C, and 100 °C).

The effect of temperature on the xylose production from decrystallized and non-decrystallized chicken manure is shown in Figure 6. The maximum mean of xylose produced was 6.29 mg xylose/g chicken manure under decrystallized chicken manure at 80 °C at a constant reaction time of 30 min. The conversion of xylose to furfural derivatives started as we increased the temperature from 80 °C to 100 °C, resulting in a decrease in the yield of xylose. The result for decrystallized chicken manure shows that the lignin structure was delignified by 75% (w/w) sulfuric acid, resulting in hemicellulose which was partially hydrolyzed and formed xylose under the acid decrystallization process. Before acid hydrolysis, decrystallized chicken manure contained some amount of xylose. As a result, during the acid hydrolysis process, some xylose was hydrolyzed and converted into furfural derivatives, leading to the decrease in the yield of xylose [19]. Therefore, as we increased the temperature from 80 °C to 100 °C, we also increased the rate of degradation of xylose into furfural derivatives. On the other hand, for non-decrystallized chicken manure, the maximum mean of xylose produced was 1.12 at 100 °C at a constant reaction time of 30 min. The increase in temperature from 60 °C to 80 °C and 100 °C showed an increase in the xylose yield from 0.40 mg xylose/g, 0.56 mg xylose/g to 1.12 mg xylose/g chicken manure. As we increased the temperature, the xylose produced also increased. This showed the potential of chicken manure to be utilized as a useful product with high-value impact [20].

3.5. Statistical Analysis

In summary, the three parameters, temperature, acid concentration, and acid decrystallization, were evaluated to indicate their significance for the yield of glucose and xylose from chicken manure. Acid decrystallization, acid concentration, and temperature have p-values of less than 0.0001, indicating that these parameters are significant to the production of glucose and xylose from chicken manure. Acid decrystallization is the most significant parameter for the production of glucose and xylose from chicken manure, followed by acid concentration. Temperature is the least significant among the three parameters.

3.6. Preliminary Biometrics and Environmental Assessment

To assess industrial viability, a theoretical projection was performed based on the optimal yield (54.68 mg total sugar/g CM). Processing 1 tonne of dry CM would theoretically yield ~54.7 kg of fermentable sugars. While acid hydrolysis costs are often cited as a barrier, the use of CM as a zero-cost waste feedstock offsets material expenses [21]. Energy analysis using the specific heat of the slurry (CP ≈ 4.18 kJ/kg-K) indicates a theoretical thermal requirement of only 313.5 kJ/kg (0.087 kWh/kg) to reach 100 °C, suggesting low operational energy costs [22]. Environmentally, this rapid conversion prevents the methane emissions typically associated with manure decomposition in landfills [23]. Furthermore, the neutralization byproduct (gypsum) can be utilized as a soil conditioner rather than requiring disposal, supporting a circular economy model [24].

4. Conclusions

Acid decrystallization plays an important role in the hydrolysis of cellulose and hemicellulose. Sulfuric acid (75% w/w) effectively reduced the cellulose crystallinity, dismantled the lignocellulosic structure, and increased the porosity of the samples which indicates faster degradation of cellulose. Concentrated sulfuric acid efficiently decrystallized the structure of lignin before acid hydrolysis of hemicellulose and cellulose to produce higher yields of glucose and xylose. Acid concentration portrayed an inverse relationship with both glucose and xylose yield for acid decrystallized chicken manure samples. For non-decrystallized chicken manure samples, on the other hand, acid concentration presented a proportional relationship with both glucose and xylose yield. Hydrolysis temperature had a proportional relationship with both glucose and xylose yield. To maximize the yield of glucose and xylose for acid decrystallized chicken manure samples, the production of glucose should operate at low acid concentration and high temperature. To maximize the yield of glucose and xylose for non-decrystallized chicken manure samples, the production of glucose should operate at high acid concentrations and high temperatures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.V.C.R. and J.G.O.; methodology, J.E.S., J.K.A., I.C.B., P.J.S. and D.N.V.; validation, R.V.C.R. and J.G.O.; formal analysis, J.E.S.; investigation, J.K.A.; visualization, D.N.V.; supervision, R.V.C.R. and J.G.O.; project administration, R.V.C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Philippine Statistics Authority. Chicken Situation Report: July to September 2023; Special Release No. 2023-SSO-201; PSA: Quezon City, Philippines, 2023.

- Gomez, C.J.J. Philippine Chicken Industry Update: Market Trends, Projected Shortages, Rising Imports, Price Surges, and DOST-PCAARRD Innovations for Stability. ISPweb–PCAARRD DOST. 2024. Available online: https://ispweb.pcaarrd.dost.gov.ph/philippine-chicken-industry-update-market-trends-projected-shortages-rising-imports-price-surges-and-dost-pcaarrd-innovations-for-stability/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Department of Agriculture–Bureau of Animal Industry. Philippine Poultry Broiler Industry Roadmap 2022–2040; Department of Agriculture–Bureau of Agricultural Research: Quezon City, Philippines; UPLB Foundation, Inc.: Quezon City, Philippines; Philippine Council for Agriculture and Fisheries: Quezon City, Philippines, 2022.

- Kocetkovs, V.; Zvirbule, A. Chicken manure as closed-loop circular economy product of poultry industry. In Proceedings of the 24th International Scientific Conference Engineering for Rural Development, Jelgava, Latvia, 21–23 May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.; Eraky, M.; Osman, A.I.; Ai, P.; Zhou, Z.; Meng, F.; Rooney, D.W. Bioenergy production from chicken manure: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 2707–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manogaran, M.D.; Hakimi, M.; Chan, X.Y.; Shamsuddin, R.; Lim, J.W.; Suparmaniam, U. Biomass waste resources as inoculum for anaerobic digestion of chicken manure for biogas generation. AIP Conf. Proc. 2025, 3225, 040004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapovalov, Y.; Zhadan, S.; Bochmann, G.; Salyuk, A.; Nykyforov, V. Dry Anaerobic Digestion of Chicken Manure: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, C.; Pong, F.; Sen, A. Chemical conversion pathways for carbohydrates. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 40–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Song, T.; Su, H. Waste Fermentation for Energy Recovery. In Waste-to-Energy; Abomohra, A.E.-F., Wang, Q., Huang, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.M.S.; Taveira, I.C.; Maués, D.B.; de Paula, R.G.; Silva, R.N. Advances in fungal sugar transporters: Unlocking the potential of second-generation bioethanol production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, C.; Chang, H.-M.; Li, Z.; Jameel, H.; Zhang, Z. A Method for Rapid Determination of Sugars in Lignocellulose Prehydrolyzate. BioResources 2012, 8, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldesenbet, A.G.; Gizachew, S.; Chandravanshi, B.S. Bio-ethanol production from poultry manure at Bonga Poultry Farm in Ethiopia. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 7, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Shamsuddin, M.R.; Aqsha; Lim, S.W. Characterization of Chicken Manure from Manjung Region. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 458, 012084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, Y.P.; Putra, R.D.D.; Widyaya, V.T.; Ha, J.-M.; Suh, D.J.; Kim, C.S. Comparative study on two-step concentrated acid hydrolysis for the extraction of sugars from lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 164, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfaardt, F.J.; Fernandes, L.G.L.; Oliveira, S.K.C.; Duret, X.; Görgens, J.F.; Lavoie, J.-M. Recovery approaches for sulfuric acid from the concentrated acid hydrolysis of lignocellulosic feedstocks: A mini-review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2021, 10, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Li, F.-L.; Lu, M.; Fang, X.-C. Emerging technologies for the pretreatment of lignocellulosic materials for bio-based products. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 104, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Wen, Z.; Chen, S. Acid hydrolysis of fibers from dairy manure. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 1687–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saady, N.M.C.; Rezaeitavabe, F.; Espinoza, J.E.R. Chemical Methods for Hydrolyzing Dairy Manure Fiber: A Concise Review. Energies 2021, 14, 6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taveira, I.C.; Carraro, C.B.; Nogueira, K.M.V.; Pereira, L.M.S.; Bueno, J.G.R.; Fiamenghi, M.B.; dos Santos, L.V.; Silva, R.N. Structural and biochemical insights of xylose MFS and SWEET transporters in microbial cell factories: Challenges to lignocellulosic hydrolysates fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1452240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilando, A.C.; Rubi, R.V.D.; Lacsa, F.J.F. Utilization of low-cost waste materials in wastewater treatments. In Integrated and Hybrid Process Technology for Water and Wastewater Treatment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Kumar, V.; Singh, J.; Sharma, N. Poultry Manure and Poultry waste management: A review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2020, 9, 3483–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, M.E.; Zambon, M.D.; Area, M.C.; Curvelo, A.A.S. Low liquid-solid ratio fractionation of sugarcane bagasse by hot water autohydrolysis and organosolv delignification. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 65, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Ward, A.J.; Moset, V.; Møller, H.B. Methane emission during on-site pre-storage of animal manure prior to anaerobic digestion at biogas plant: Effect of storage temperature and addition of food waste. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 225, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amezketa, E.; Aragüés, R.; Gazol, R. Efficiency of sulfuric acid, mined gypsum, and two gypsum by-products in soil crusting prevention and sodic soil reclamation. Agron. J. 2005, 97, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).