Abstract

The article describes the use of light dynamic penetration on potentially unstable terrain. Geophysical and geological surveys were carried out, including two core boreholes with samples for lab analysis. DPL (Dynamic penetration light) results were compared with lab-determined soil properties to verify its use in geotechnical surveys.

1. Introduction

Landslides and slope deformations represent significant environmental risks that impact both construction and mineral extraction industries. Slope instability arises not only due to anthropogenic interventions but also on natural slopes composed of both soils and rocks. The activation of instability can occur very rapidly or develop over an extended period, gradually disrupting otherwise stable environmental conditions [1].

For the prevention and remediation of high-risk areas, it is essential to carry out geotechnical investigations. One suitable method is light dynamic penetration (DPL). This method was originally designed for rapid field testing during the design of linear structures, with the aim of determining bearing capacity parameters, degree of compaction, and soil consolidation. However, its application has since expanded to include investigations of areas affected by slope instabilities and landslides [2].

Penetration tests are among the oldest geotechnical methods. Since ancient times, various probing tools and procedures have been used to verify the properties of foundation soils. Modern penetration methods have been developing especially since the early 20th century, with standardization efforts taking place, for example, at the 1953 ISSMFE (International Society on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering) conference in Zurich. As a result, an international committee for the standardization of penetration tests was established, which recommended the use of German dynamic penetrometers, Dutch static penetrometers, and Swedish probing procedures as the European standard [1].

2. Principle of Dynamic Penetration

The general principle of dynamic penetration tests is to measure the resistance of soils (or semi-rocky materials) against the penetration of a cone [3]. In DPL, the number of hammer blows required to drive the cone 100 mm into the ground is recorded. This allows for the estimation of the soil’s resistance to penetration and, based on the collected data, the determination of basic physico-mechanical properties (e.g., cohesion, internal friction angle, and degree of compaction) [4]. Dynamic tests complement direct methods of geotechnical investigation, especially data obtained from borehole drilling. Based on the results obtained from dynamic probing, it is possible to determine:

- boundaries between individual geological layers;

- indicative strength and deformation properties of soils;

- relative density index of cohesionless soils;

- consistency state of cohesive soils;

- suitability of the area for the use of shoring systems (e.g., sheet pile walls);

- localization of potential slip surfaces;

- identification of zones affected by suffosion.

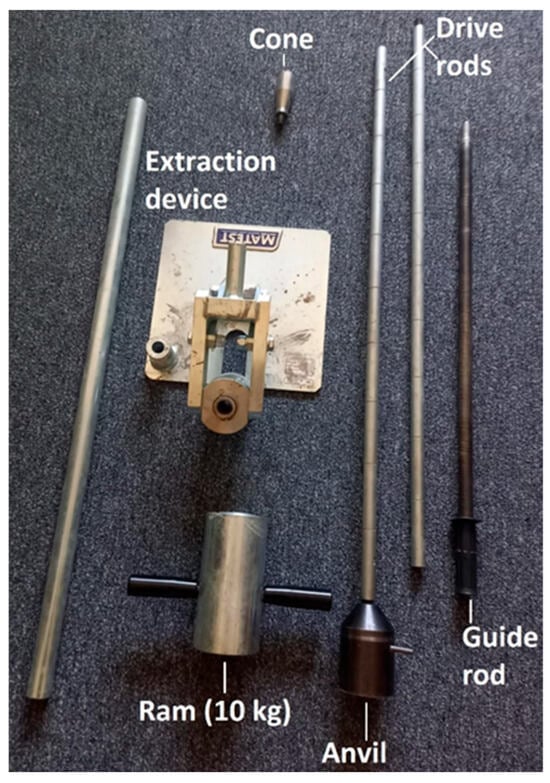

The equipment used for Light Dynamic Penetration (DPL) consists of six main components (Figure 1):

- Anvil—transmits the impact force from the hammer;

- Hammer—a weight of 10 kg ± 0.1 kg, falling from a height of 500 mm ± 10 mm;

- Guide rod—ensures that the hammer falls with minimal friction;

- Drive rods—calibrated rods marked at 10 cm intervals;

- Cone—with a specified apex angle of 90°, either fixed or detachable;

- Extraction device—used to pull the rods out after the measurement is completed.

Figure 1.

Basic parts of DPL.

3. Mathematical Expression of Penetration Resistance

The number of blows per 10 cm is only indicative, as it does not account for the influence of the rod weight or the shaft friction. Therefore, a parameter called the dynamic penetration resistance (qd) is introduced, which compensates for these effects. The value of qd is calculated using the following formulas [5]:

| rd | Specific dynamic resistance | [Pa]; |

| qd | dynamic penetration resistance | [Pa]; |

| Etheor | theoretical energy generated by the impact | [J]; |

| A | base area of the cone | [m2]; |

| e | average penetration per blow | [m]; |

| m | mass of the hammer | [kg]; |

| m′ | total mass of the drive rods | [kg]; |

| g | gravitational acceleration | [m/s2]. |

4. Measured Location

The evaluated plot was deliberately selected due to the presence of several indicators suggesting slope movements and potential slope instability, which necessitated a detailed engineering geological investigation. During the initial reconnaissance, a so-called “drunken forest” was observed—i.e., a stand of trees with trunks tilted in various directions. This phenomenon typically indicates recent slope movements to which the vegetation has not yet adapted by straightening. Another important indicator was an older landslide located on the northern part of the site, which could become reactivated under unfavourable climatic conditions.

These indications are further supported by unfavourable geological conditions—namely, a subsurface composed of flysch rocks with a shallow groundwater table—and by adverse geomorphological features. The entire plot is situated on a slope whose toe is being eroded by a watercourse, resulting in material loss and a negative mass balance of the slope.

Since the construction of a residential house is planned on this parcel, a preliminary investigation was carried out using the geophysical method of electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) and dynamic penetration testing (DPL). The results were subsequently verified through a detailed engineering-geological survey.

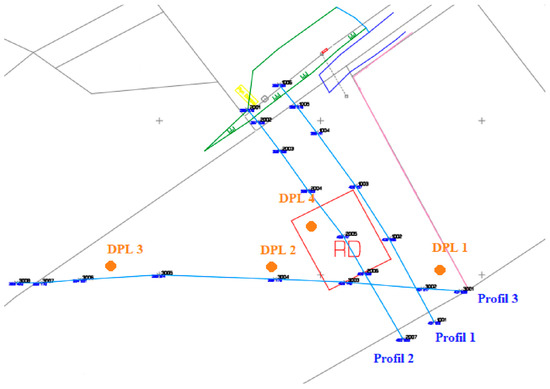

In the area of interest, three measurement profiles were carried out using the ERT method (Figure 2), with their placement corresponding to the planned location of the future building. Two transverse profiles were conducted across the full width of the parcel, and one longitudinal profile was completed along the upper part of the site.

Figure 2.

Situation map of individual ERT and DPL profiles.

For the dynamic penetration testing (DPL), four points were designated: three of them followed the path of longitudinal profile no. 3, while the fourth point was located at the edge of the future building, near transverse profile no. 2.

5. DPL Measurements

During the execution of DPL testing in the investigated area, two main factors were identified that complicated the measurements. The first was the presence of pressurized groundwater encountered at all penetration points. After the probe was withdrawn, water and disintegrated clayey soil were observed flowing out of the borehole (Figure 3). The groundwater level at points DPL1–DPL3 was located at a depth of approximately 2.4 m, and at point DPL4, even as shallow as 1.6 m (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

HPV measurement using an electrocontact level meter (left), sample of clay soil in a liquid state on a DPL (right).

Repeated measurements after the completion of penetrations revealed that the groundwater level rose to approximately 1.3 m at all tested points, indicating the presence of artesian (confined) groundwater. At point DPL4, the rise was less significant, as the initial measurement had already shown a higher starting level.

The second complicating factor—confirmed later by borehole investigation—was the nature of the soils: exclusively clays and claystones, which are characterized by high shaft friction. This leads to distorted results and complicates the interpretation of this method.

The measured dynamic resistances ranged from 0.5 MPa to 15 MPa, with values up to 15 MPa occurring at shallow depths. These high values were likely caused by a combination of pressurized groundwater and increasing shaft friction. Therefore, in some cases, the test had to be terminated upon reaching 50 blows per 10 cm, as stipulated by the standard.

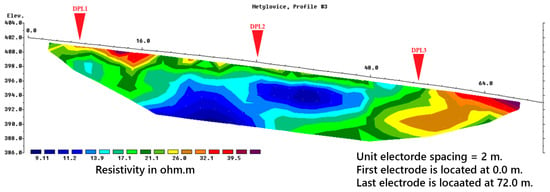

The ERT method identified zones with low electrical resistivity (Figure 4), which may correspond to water-saturated layers. An interesting feature is the green-coloured horizon, which functions as an insulating layer above the pressurized water. After this layer was disturbed during the DPL testing, a rapid increase in dynamic resistance was observed.

Figure 4.

Profile 3 evaluated using the ERT method at the measured location.

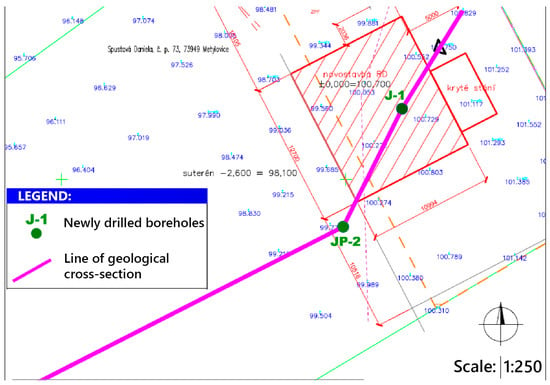

For a detailed interpretation of the results, a core drilling survey was essential. Two boreholes, J-1 and JP-2, were carried out near the planned construction site (Figure 5). The boreholes were drilled using core drilling methods to depths of 4 m (J-1) and 5 m (JP-2). An infiltration test was also performed in borehole JP-2.

Figure 5.

Location of individual geological boreholes with the geological section line marked.

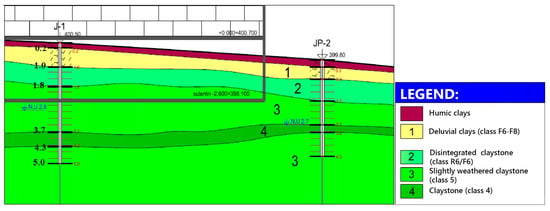

Based on the collected data, a conceptual geological cross-section was developed, enabling a more accurate interpretation of the results from the dynamic penetration tests. The following figure (Figure 6) presents a detailed excerpt of this documentation, focusing on the area surrounding both completed boreholes to enhance clarity.

Figure 6.

Detail from the geological profile.

The geological cross-section illustrates the course of both boreholes and the approximate stratification of individual soil layers. The planned family house, including the proposed basement, is marked in grey. By comparing the dynamic resistances obtained using the DPL method with the results of the borehole survey, it is possible to approximately determine the boundaries between soil layers.

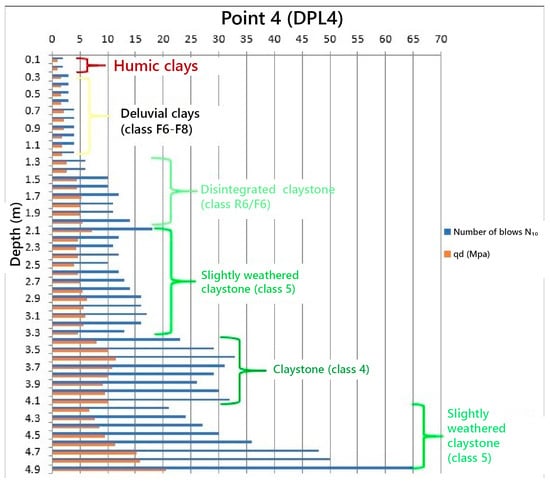

The penetration point closest to borehole J-1 was point DPL4 (Figure 7); therefore, a mutual comparison was carried out. The upper layer of humic clays (marked in dark red) was confirmed in the borehole down to a depth of approximately 0.2 m. At the same depth in profile DPL4, a dynamic resistance value of 1.03 MPa was recorded, which gradually increased to an average value of 1.75 MPa. This trend suggests that the boundary between the humic layer and the underlying material is located at a depth of approximately 1.0–1.2 m, slightly deeper than indicated by the borehole (0.8 m).

Figure 7.

Graphical evaluation of DPL point 4 at the measured location.

In the deeper strata, it was challenging to distinguish the boundary between disintegrated claystone (class R6/F6) and slightly weathered claystone (class 5). From a depth of 1.2 m to approximately 3.3 m, the dynamic resistance values remained relatively constant (ranging between 5 MPa and 3 MPa), which without borehole data could lead to the erroneous interpretation of a single homogeneous layer. It is important to note that groundwater was detected within this zone, which may have influenced and distorted the results.

From a depth of 3.3 m, a layer with the highest dynamic resistance values becomes apparent. It was identified through borehole investigation as a more compact claystone (class 4) within the interval of 3.7–4.3 m. The DPL measurement indicated this layer slightly higher, approximately between 3.3 and 4.1 m, while the thickness of the layer corresponded with that observed in the borehole profile.

The last layer consisted once again of slightly weathered claystone, with its transition indicated in the DPL measurement by a drop in dynamic resistance at a depth of approximately 4.2 m. This decrease signalled a transition into a less consolidated material.

6. Conclusions

The use of light dynamic penetration testing (DPL) proved to be a fully suitable method for preliminary or supplementary geotechnical investigation at this site. In combination with electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), it enabled the identification of key risks and the determination of the need for further detailed engineering–geological investigation, which subsequently built upon the results of the DPL and ERT measurements. A major benefit was the determination of the groundwater level at individual penetration points and the accurate interpretation of geological layer boundaries, despite the challenging conditions posed by the presence of clays and claystones.

The ERT method proved helpful in localizing potentially water-bearing horizons. Interestingly, even areas with higher resistivity values (e.g., at points DPL1 and DPL3) were found to contain water-bearing horizons, like point DPL2, where such conditions had been anticipated based on the ERT results.

Based on the results of all three independent methodological approaches, it is recommended that the findings to date (elevated groundwater levels, unsuitable soils, soil consistency conditions, etc.) be considered during the design of the residential building. Furthermore, it is advised to postpone the start of construction work on this plot by at least one year. During this period, a slope stability assessment should be prepared, and geotechnical monitoring should be established—such as an inclinometer borehole—along with at least two inclinometric measurements to confirm or refute the presence of active slope movements.

The light dynamic penetration test proved to be an effective indirect method for the geotechnical investigation of a landslide-prone area. Its main advantages include fast and simple execution, equipment mobility, low time demands, and the ability to obtain initial information about the mechanical properties of soils without the need for sampling. However, as an indirect method, it also has certain limitations—primarily its increased sensitivity to local environmental conditions, which can significantly affect the interpretation of results. The measured values may be influenced by various factors, such as the presence of pressurized groundwater or soils with high shaft friction, as was the case in this study. These factors can complicate the clear interpretation of results without additional supporting data. For these reasons, it is advisable to combine the light dynamic penetration test with other methods, such as geophysical techniques like electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), or to use it as a supplementary tool within a detailed engineering–geological investigation.

The obtained results are consistent with the findings of previous studies [2] that focused on similar landslide areas. These studies confirmed the suitability of combining DPL and ERT methods for assessing geotechnical conditions and identifying risk zones. In the present research, this approach was further developed by incorporating direct investigation through borehole drilling, which helped to verify and expand the interpretation obtained from indirect measurements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.K. and L.C.; methodology, V.K.; validation, L.C. and A.Š.; formal analysis, V.K.; investigation, A.Š.; data curation, A.Š.; writing—original draft preparation, V.K.; writing—review and editing, L.C. and A.Š.; visualization, V.K.; supervision, L.C.; project administration, V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the Department of Mining Engineering and Safety, VSB–Technical University of Ostrava.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to confidentiality restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Král, T.; Široký, T.; Janega, M.; Lazorisak, P.; Molínek, O. Digitization of Measured Data in Landslide Area. In Proceedings of the 18th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM 2018, Albena, Bulgaria, 2–8 July 2018; Volume 18, pp. 737–742, ISBN 978-619-7408-36-2. [Google Scholar]

- Široký, T.; Šancer, J. Experience with Light Dynamic Penetration in a Landslide Locality. GeoSci. Eng. 2019, 65, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Široký, T.; Lazorisak, P.; Janega, M.; Král, T. Possibilities of Using Light Dynamic Penetration in the Landslide Area. In Proceedings of the 18th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM 2018, Albena, Bulgaria, 2–8 July 2018; Volume 18, pp. 547–552, ISBN 978-619-7408-36-2. [Google Scholar]

- Obert, L. Dynamické Penetračné Skúšky v Inžiniersko-Geologickom Prieskume. Ph.D. Thesis, Comenius University, Bratislava, Slovakia, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- ČSN EN ISO 22476-2; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Field Testing—Part 2: Dynamic Probing. Czech Standards Institute: Prague, Czech Republic, 2005.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).