Abstract

The increasing resistance of Candida tropicalis to conventional antifungal agents has necessitated the development of effective, biocompatible alternatives derived from natural sources. Garlic (Allium sativum), known for its potent antimicrobial activity, contains 33 bioactive sulfur compounds, some of them being allicin, ajoene, and diallyl sulfides, that exhibit strong antifungal effects. However, the clinical application of garlic extract in pharmaceutical formulations remains limited due to its chemical instability, rapid degradation, and limited bioavailability. This review highlights recent advancements in pharmaceutical processing and particle engineering approaches to enhance the stability, delivery, and therapeutic efficacy of garlic extract-based antifungal formulations. Key strategies such as nanoparticle encapsulation, nanoemulsification, advanced drying techniques, and hydrogel-based delivery systems are discussed as effective approaches to enhance the stability and antifungal performance of garlic extract formulations. Special attention is given to hydrogel-based systems due to their excellent mucoadhesive properties, ease of application, and sustained release potential, making them ideal for treating localized C. tropicalis infections. The review also discusses formulation challenges and in vitro evaluation parameters, including minimum inhibitory concentration, minimum fungicidal concentration, and biofilm inhibition. By analyzing recent findings and technological trends, this review underscores the potential of garlic extract-based particle-engineered systems as sustainable and effective antifungal therapies. The scope of this review includes an in-depth evaluation of garlic extract-derived formulations, the application of particle processing technologies, and their translational potential in the design of next-generation antifungal delivery systems for managing C. tropicalis infections.

1. Introduction

C. tropicalis is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that causes candidiasis, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. It remains a critical global health threat due to its high morbidity and mortality rates [1]. It is frequently isolated from bloodstream infections, urinary tract infections, and deep-seated candidiasis, especially in patients with malignancies, neutropenia, or those undergoing prolonged antibiotic or corticosteroid therapy. Candida species is generally classified as Candida albicans & Non-Candida Albicans Candida (NCAC). Among the NCAC species, C. tropicalis has gained attention due to its increasing prevalence, high virulence potential, and ability to form robust biofilms, which significantly complicate treatment efforts. It is included as a ‘high priority’ fungal pathogen on the most recent World Health Organization (WHO) list of the most dangerous fungal infections, ranked second only to the ‘critical priority’ category [2,3]. The burden of this fungal infection has intensified in the post-COVID-19 era, driven by the growing number of immunocompromised individuals and increased hospitalization rates, which predispose patients to severe co-infections such as invasive candidiasis. Major virulence factors in C. tropicalis are biofilm, drug resistance, and morphological transition [4]. All these challenges underscore the urgent need for safe, effective, and naturally derived antifungal alternatives [5,6].

In recent years, the global incidence of antifungal resistance has become an increasing public health concern, particularly among Candida species isolated from invasive infections. Retrospective surveillance studies have documented rising resistance to commonly used antifungal agents, especially azole drugs, in non-albicans Candida species such as C. tropicalis, with noticeable trends of reduced susceptibility in clinical isolates over time [7]. In one regional study, C. tropicalis exhibited higher azole resistance rates compared with other Candida species, reflecting the growing therapeutic challenge posed by this pathogen [8]. Biofilm formation further exacerbates this resistance by creating a protective matrix that increases minimal inhibitory concentrations to frontline drugs such as fluconazole [4]. These evolving resistance patterns underscore the limitations of current antifungal therapies and the urgent need to explore alternative or adjunctive strategies. Against this backdrop, garlic extract-based formulations, when integrated with advanced pharmaceutical processing and particle engineering approaches, offer a promising route to enhance antifungal efficacy and overcome resistance mechanisms associated with C. tropicalis infections.

Garlic (Allium sativum) has long been valued for its potent antimicrobial and antifungal properties, primarily attributed to its rich composition of organosulfur compounds such as allicin, ajoene, diallyl sulfides, and S-allylcysteine [9]. These bioactive molecules exhibit strong inhibitory effects against Candida spp., disrupting cell wall integrity, interfering with enzyme activity, and impairing biofilm formation [10]. However, the therapeutic application of garlic extracts is limited by their instability, volatility, and poor solubility, leading to reduced bioavailability and inconsistent efficacy in pharmaceutical formulations [11].

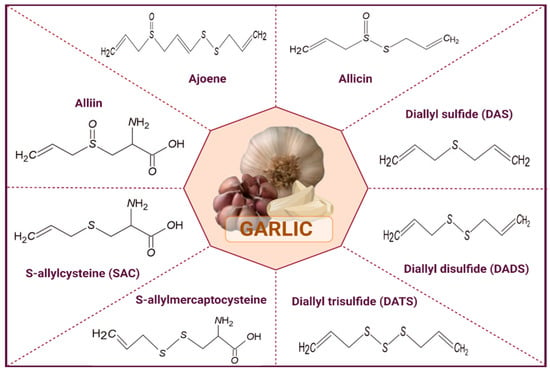

Garlic is rich in pharmacologically active organosulfur derivatives, which are primarily responsible for its broad-spectrum therapeutic properties. These compounds are generated through enzymatic conversion of alliin to allicin upon tissue disruption and subsequently transform into more stable derivatives such as diallyl sulfide (DAS), diallyl disulfide (DADS), diallyl trisulfide (DATS), ajoene, and S-allyl cysteine (SAC). Collectively, these organosulfur compounds exhibit diverse biological activities, including antifungal, antibacterial, antibiofilm, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and anticancer effects [12].

Among them, allicin demonstrates potent antifungal activity by disrupting thiol-containing enzymes, altering membrane integrity, and inducing oxidative stress in fungal cells. Secondary sulfur compounds such as DADS and DATS have been shown to inhibit fungal growth and biofilm formation through modulation of mitochondrial function, induction of apoptosis-like pathways, and interference with quorum-sensing mechanisms. Ajoene exhibits notable antibiofilm and anti-virulence activity, particularly against Candida spp., by inhibiting morphogenetic transition and adhesion. In contrast, S-allyl cysteine, a water-soluble and more stable derivative, contributes antioxidant and immunomodulatory effects, enhancing host defense while improving systemic bioavailability [13].

Beyond antifungal activity, garlic organosulfur compounds have demonstrated synergistic interactions with conventional antifungal agents, reducing minimum inhibitory concentrations and potentially mitigating resistance development. However, the clinical translation of these bioactives is limited by instability, volatility, and poor pharmacokinetic profiles, thereby necessitating advanced pharmaceutical processing and particle engineering approaches to preserve their pharmacological efficacy and enable targeted delivery.

Despite their potent biological activity, isolating and stabilizing garlic’s bioactive compounds poses significant challenges that have direct implications for formulation design. The principal antimicrobial compound allicin is inherently unstable and degrades rapidly under common processing conditions, including elevated temperature, pH changes, and prolonged storage, forming secondary sulfurous decomposition products such as DADS, DATS, and vinyldithiins. Experimental studies have shown that allicin content can decline sharply with time and temperature, with rapid loss observed at temperatures ≥ 75 °C and significant degradation over days at ambient conditions, indicating the susceptibility of thiosulfinates to thermal and environmental stress [14]. In addition to thermal instability, allicin reacts readily with endogenous garlic matrix components, including amino acids (e.g., cysteine, lysine) and other organics, which further accelerates its degradation and complicates purification and quantitative isolation efforts [15]. These characteristics, combined with variability in raw material composition due to genotype, cultivation conditions, and extraction methods, make it difficult to obtain standardized, reproducible garlic bioactive preparations with consistent potency. As a result, advanced pharmaceutical processing strategies such as nanoencapsulation, nanoemulsification, controlled drying, and nanoformulation are essential to protect labile organosulfur compounds, enhance stability during storage and delivery, and ensure sufficient therapeutic exposure [16].

To overcome these limitations, pharmaceutical processing and particle engineering strategies offer promising approaches to stabilize and enhance the delivery of garlic-derived bioactives. Particle processing is a set of pharmaceutical and engineering techniques that are used to convert liquid, semi-liquid, or otherwise unstable bioactive mixtures into solid or semi-solid particles with controlled size, morphology, structure, and functionality. The primary objective is to enhance the stability, delivery efficiency, handling, and therapeutic performance of bioactive compounds by transforming them into well-defined particulate systems such as microparticles, nanoparticles, granules, or engineered powders.

Particle processing plays a crucial role in stabilizing the highly labile bioactive constituents of garlic extract, particularly allicin, ajoene, and related organosulfur compounds, which are prone to rapid degradation. The processing sequence typically begins with mechanical size-reduction operations such as milling, grinding, jet milling, and homogenization, which reduce particle size, increase surface area, and improve dispersion prior to formulation. Following this, drying techniques such as freeze-drying or spray-drying convert the liquid or semi-solid extract into stable solid powders while minimizing thermal or oxidative degradation of thermolabile constituents [17]. The resulting dried intermediates can then be encapsulated or structurally protected using polymeric, lipidic, or phospholipid-based carriers through techniques such as coacervation, liposome formation, granulation, or fluid-bed coating. More advanced particle engineering methods, including high-pressure homogenization, nanomilling, microfluidics, nanoemulsification, and supercritical fluid processing, further refine the particles into micro- or nanoscale systems with enhanced solubility, permeability, and biological activity [18]. Collectively, these operations improve the physical and chemical stability of garlic organosulfur compounds, reduce volatility, and enable controlled- or sustained-release profiles [19]. Overall, the integration of conventional and advanced particle-processing techniques transforms unstable garlic phytochemicals into robust, bioavailable, and therapeutically relevant micro- and nano-structured formulations suitable for pharmaceutical and antifungal applications.

Overall, this study highlights the growing impact of particle engineering strategies in enhancing the stability, bioavailability, and therapeutic performance of garlic extract. Advances in micro- and nano-structured delivery systems have significantly improved the protection of labile organosulfur compounds, optimized encapsulation efficiency, and strengthened antifungal activity. These developments position engineered garlic-based particles as a promising natural and sustainable platform to overcome current limitations in antifungal therapy, particularly for emerging multidrug-resistant pathogens such as C. tropicalis. By integrating conventional and advanced formulation approaches, particle-engineered garlic systems represent a viable path toward safer, more effective, and next-generation antifungal interventions.

2. Major Bioactive Constituents of Garlic

Garlic (Allium sativum) is a rich source of bioactive compounds with significant pharmaceutical potential. Its most prominent constituents are sulfur-containing compounds such as allicin, alliin, diallyl disulfide (DADS), diallyl trisulfide (DATS), S-allyl cysteine (SAC), and ajoene as shown in (Figure 1). Allicin, produced enzymatically from alliin when garlic is crushed, exhibits strong antimicrobial, antifungal, antiviral, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, making it valuable for developing antimicrobial formulations [20]. However, due to its instability, allicin is often incorporated into nanoparticles, liposomes, or hydrogels to preserve its activity. Other sulfur compounds like DADS, DATS, and ajoene contribute additional antimicrobial, anticancer, and antifungal effects, while SAC, being water-soluble and stable, is widely used in oral supplements for cardiovascular and neuroprotective benefits [9]. Garlic also contains flavonoids (quercetin, kaempferol, rutin) and saponins, which offer antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antimicrobial properties. In pharmaceutical processing, these compounds are utilized in various forms, including oral capsules, controlled-release formulations, topical gels and creams, and nutraceuticals. Encapsulation and stabilization techniques, such as microencapsulation, freeze-drying, and co-crystallization, are often employed to maintain bioactive efficacy [21]. Furthermore, garlic bioactives can act synergistically with conventional drugs, enhancing therapeutic outcomes while potentially reducing required dosages and side effects [15]. Overall, the versatile pharmacological properties of garlic compounds make them highly valuable in the design of modern pharmaceutical formulations targeting infections, oxidative stress, and chronic diseases.

Figure 1.

Major Bioactive Compounds of Garlic.

To further deepen understanding of garlic’s bioactive constituents in a clinical context, it is important to consider their absorption, metabolic fate, and bioavailability as explained in (Table 1). The principal organosulfur compound allicin is formed from alliin via alliinase upon disruption of garlic tissue, but once ingested, allicin and many of its immediate derivatives are rapidly metabolized and are often not detected in systemic circulation. Human studies indicate that allicin itself is generally not found in blood or urine after ingestion, suggesting rapid decomposition into volatile metabolites such as DAS, DADS, AMS, and other breakdown products. These volatile metabolites can be detected in breath, indicating intake and metabolism, but their precise systemic bioactivities remain incompletely understood. In contrast, water-soluble compounds such as S-allyl cysteine (SAC), which arise during aqueous processing or aging of garlic, have been shown to be absorbed intact and measured in plasma and tissues in animal models and human studies, making them useful pharmacokinetic markers of bioavailability [22]. The variations in absorption and metabolic pathways underscore the importance of formulation strategies that protect labile compounds and improve delivery of active moieties to target sites, particularly for therapeutic applications where systemic exposure or sustained concentrations are desirable [23].

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetics of Major Garlic Bioactive Compounds.

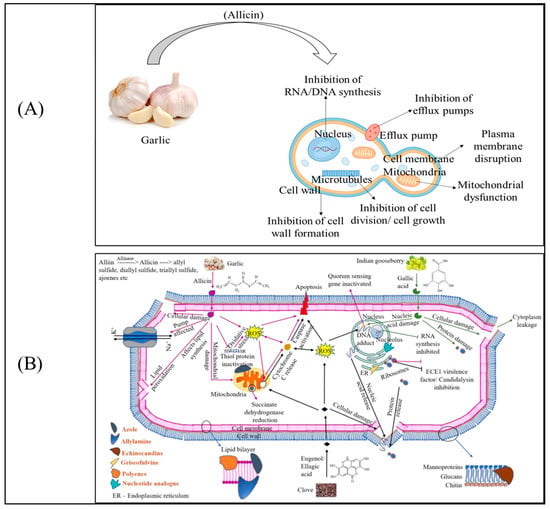

3. Mechanism of Action of Garlic in Treating C. tropicalis

Garlic-derived allicin exerts antifungal activity through a multifaceted mode of action that targets several essential cellular pathways in C. tropicalis [25]. Upon exposure, allicin rapidly penetrates the fungal cell due to its small size and high reactivity. Its primary biochemical target is thiol-containing proteins, and this broad thiol-reactivity underpins many of the inhibitory effects shown in (Figure 2). One of the earliest responses is disruption of the plasma membrane, where allicin reacts with membrane-associated proteins and phospholipids, leading to compromised membrane integrity, leakage of intracellular components, and loss of membrane potential [26].

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of antifungal activity of garlic against C. tropicalis. (A) Simplified representation of allicin interaction with fungal cells demonstrating interference with cell wall synthesis, membrane integrity, efflux pumps, mitochondrial activity, and nucleic acid synthesis. (B) Detailed molecular pathways involving ROS induction, membrane disruption, protein oxidation, and inhibition of nucleic acid synthesis, efflux pumps, and virulence signals  For garlic,

For garlic,  Indian gooseberry and

Indian gooseberry and  clove (Reproduced from [25]).

clove (Reproduced from [25]).

For garlic,

For garlic,  Indian gooseberry and

Indian gooseberry and  clove (Reproduced from [25]).

clove (Reproduced from [25]).

Allicin also affects mitochondrial function, where interaction with thiol-dependent enzymes of the respiratory chain results in reduced ATP generation and accumulation of reactive oxygen species. This mitochondrial impairment contributes to metabolic arrest and eventual cell death. Another critical action comes from its ability to disturb cell wall biosynthesis [27]. By targeting enzymes involved in β-glucan and chitin production, allicin weakens the fungal cell wall, making the organism more susceptible to osmotic and environmental stress. It also highlights the compound’s inhibitory effect on cell division and microtubule organization, suggesting interference with structural proteins required for mitosis and hyphal elongation.

Furthermore, allicin inhibits RNA and DNA synthesis, likely by modifying thiol-containing proteins involved in nucleic acid replication and transcription. This results in impaired genetic material synthesis and diminished cell proliferation [28]. In addition, allicin suppresses the activity of efflux pumps, particularly ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, which are major contributors to azole resistance. By impairing pump function, allicin enhances intracellular accumulation of antifungal drugs and strengthens combination therapy outcomes [29].

Collectively, the mechanisms emphasize that allicin exerts its antifungal effect through simultaneous disruption of cell wall formation, membrane integrity, efflux pump activity, mitochondrial function, and nucleic acid synthesis. This multi-targeted mode of action explains its potency against drug-resistant Candida strains and underscores its relevance as a promising adjunct in antifungal therapy.

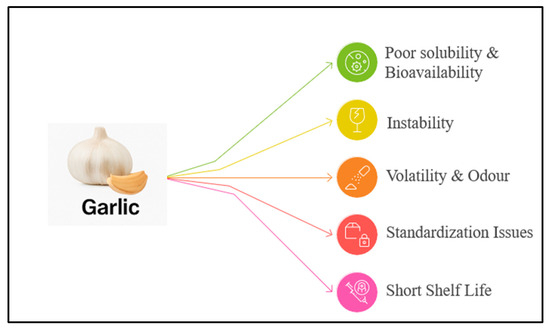

4. Challenges in Formulating Garlic Extract

Formulating garlic extract for pharmaceutical use presents several significant challenges as shown in (Figure 3), primarily due to the chemical instability of allicin. Allicin degrades rapidly under physiological and processing conditions, its half-life shortens at elevated temperature, non-neutral pH, or in the presence of endogenous amino acids [14]. The enzyme responsible for generating allicin, alliinase, is itself sensitive to pH, buffers, salts, and storage conditions, making consistent in situ synthesis difficult to maintain [30]. Furthermore, allicin’s reactivity toward thiols and other nucleophiles makes it prone to rapid degradation or conversion to other sulfur compounds, which affects both potency and stability. The pH of aqueous formulations plays a crucial role: allicin is most stable in mildly acidic to neutral pH (around pH 5–6), but it degrades quickly at more extreme pH values [31]. Moreover, storage temperature and solvents influence its preservation, long-term stability requires careful control, and even then, allicin may degrade within days or weeks depending on formulation type.

Figure 3.

Major Challenges Associated in Formulating Garlic Extract.

In terms of shelf-life assessment, both accelerated and real-time stability studies are typically employed following International Council for Harmonisation (ICH)-guided conditions (40 °C/75% Relative humidity (RH) for accelerated testing and 25 °C/60% RH for long-term storage). Stability testing commonly involves chemical assays for allicin content (HPLC/UPLC), antioxidant assays (DPPH, ABTS), and periodic evaluation of moisture content, colour change, odour intensity, pH shift, and microbial load. Encapsulated or nano-engineered formulations generally exhibit extended stability, retaining allicin activity for months rather than days, highlighting the importance of carrier-based protection. Despite improvements, maintaining a predictable degradation profile over extended storage remains difficult, and there is still limited long-term stability data for garlic-based pharmaceutical products under varied climatic zones [7].

In addition to pH and temperature, the choice of formulation matrix significantly influences the stability and shelf life of allicin and other garlic bioactives. Aqueous formulations tend to accelerate degradation due to enhanced hydrolytic reactions and increased exposure to water and dissolved oxygen, leading to rapid breakdown of allicin into secondary sulfur compounds. Stability studies have demonstrated that allicin is particularly sensitive in aqueous environments, degrading quickly unless pH is maintained within a narrow range and storage conditions are rigorously controlled [32,33]. Conversely, colloidal and lipid-rich delivery systems provide a more protective microenvironment, limiting direct contact with water and reducing oxidative degradation. For example, phytosome systems and emulsion gels have been shown to improve the physical and chemical stability of allicin by encapsulating the bioactive within lipid or protein-polysaccharide interfaces, protecting it against thermal and environmental stress [28]. These observations suggest that oil-based, lipid carrier, and nano-encapsulated formulations may offer superior shelf-life performance compared with simple aqueous solutions, providing a practical guideline for formulation design in future research and product development.

Overcoming these challenges may involve optimizing micro- and nano-encapsulation systems, co-processing with stabilizers (cyclodextrins, lipids, biodegradable polymers), and employing modified-atmosphere or oxygen-free packaging to reduce oxidative breakdown [15]. Future research should focus on well-designed multi-factor stability studies, kinetic modelling of allicin degradation, and comparative evaluation of different particle-engineering techniques under ICH Q1A(R2) conditions.

Despite their potent biological activity, garlic-derived organosulfur compounds, particularly allicin, exhibit poor physicochemical stability, rapid degradation, and high volatility, which significantly limit their pharmaceutical applicability. Allicin readily decomposes in aqueous environments, at elevated temperatures, and in the presence of thiol-containing biomolecules, resulting in reduced shelf life and inconsistent bioactivity. These formulation challenges necessitate the development of advanced encapsulation and particle engineering strategies to protect labile garlic bioactives, improve stability, and enable controlled delivery.

4.1. Liposomal Systems

Liposomal encapsulation represents one of the most effective approaches for stabilizing allicin and related sulfur compounds. Phospholipid bilayers act as protective barriers, shielding allicin from hydrolysis, oxidation, and direct exposure to environmental stressors. Recent studies have demonstrated that liposome-loaded garlic extracts exhibit significantly improved chemical stability, higher encapsulation efficiency, and sustained antimicrobial activity compared to free extracts. Moreover, liposomal systems reduce volatility and odour while facilitating controlled release, thereby enhancing pharmaceutical suitability [34].

4.2. Polymeric & Lipid Nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles (chitosan, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) and lipid-based carriers such as solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) further enhance the stabilization of garlic bioactives. These systems encapsulate allicin within solid or semi-solid matrices, reducing exposure to moisture and oxygen while enabling sustained or targeted release. Nanoparticle-based encapsulation has been shown to improve physicochemical stability, protect thermolabile compounds during processing, and enhance bioavailability through nanoscale size reduction and surface modification [14].

4.3. Nanoemulsions & Advanced Systems

Nanoemulsification provides an additional strategy for stabilizing volatile garlic constituents by dispersing them within nanosized oil droplets stabilized by surfactants. Garlic extract-loaded nanoemulsions demonstrate high encapsulation efficiency, controlled release behaviour, and improved storage stability. Emerging technologies such as microfluidics, electrospraying, and supercritical fluid-based particle formation further allow precise control over particle size, morphology, and release kinetics, offering scalable solutions for stabilizing sensitive phytochemicals [35].

Collectively, these encapsulation and particle engineering approaches directly address the inherent instability of allicin and other organosulfur compounds, transforming garlic extract from a chemically fragile natural product into a stable, reproducible, and pharmaceutically viable antifungal formulation.

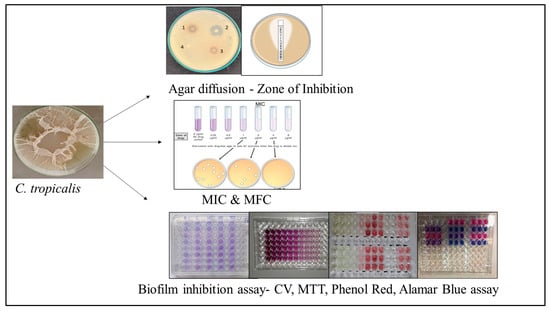

5. Evaluation of Antifungal Efficacy of Garlic Extract-Based Formulations Against C. tropicalis

The antifungal activity of garlic extract and its engineered pharmaceutical formulations have been widely assessed using a combination of in vitro experimental models as shown in (Figure 4). These established methods allow researchers to evaluate the inhibitory, fungicidal, and antibiofilm properties of garlic-derived bioactive compounds, particularly allicin and organosulfur nanoparticles, against C. tropicalis. Collectively, these assays serve as the primary benchmark tools reported in antifungal research.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of antifungal efficacy of garlic extract against C. tropicalis. Agar-based disc diffusion assays show zones of inhibition, while MIC and microtiter plate assays demonstrate concentration-dependent growth inhibition.

5.1. Agar Diffusion Assays (Qualitative or Semi-Quantitative Screening Methods)

Agar well diffusion and disc diffusion methods are commonly used as qualitative or semi-quantitative screening assays to evaluate the antifungal activity of garlic extracts and particle-based formulations. In these techniques, the diameter of the inhibition zone reflects how effectively the bioactive compounds diffuse through the agar and suppress C. tropicalis. Strip-based diffusion assays, such as gradient strip or E-strip methods, further allow assessment of concentration-dependent responses by creating a predefined gradient of the antifungal agent on the strip. These assays help establish the relationship between garlic extract concentration and the corresponding zone of inhibition, enabling comparison of potency, release behaviour, and diffusion characteristics among different formulations [6,36].

5.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Fungicidal Concentration (MFC)

The MIC and MFC values are routinely reported as quantitative indicators of antifungal strength. MIC determination using broth microdilution assays reveals the minimum concentration required to inhibit visible growth of C. tropicalis. MFC determination further establishes the concentration required to achieve complete fungal killing. When garlic extract is incorporated into nanoemulsions, liposomes, or polymeric particles, changes in MIC/MFC values are often used to demonstrate enhanced stability, controlled release, or improved cellular uptake relative to unprocessed extracts [37,38,39].

5.3. Biofilm Inhibition Evaluation Assays

C. tropicalis exhibits strong biofilm-forming ability and notable resistance to antifungal agents, making biofilm-specific assays essential when assessing garlic extract-based formulations. The crystal violet (CV) microtiter plate assay is the most commonly used method to quantify total biofilm biomass, where decreases in absorbance indicate disruption or inhibition of the biofilm matrix. To evaluate cellular activity within the biofilm, metabolic assays such as XTT, MTT, phenol red and Alamar Blue (resazurin), based methods are widely employed, providing information on viability, respiration, and proliferative capacity. These approaches help differentiate between biomass reduction and metabolic suppression. Advanced analytical techniques including confocal microscopy further elucidate how garlic-derived organosulfur compounds affect biofilm architecture, hyphal development, and extracellular polymeric substance production [25,40,41].

MIC and MFC assays are widely used as initial screening tools for evaluating antifungal activity, they have inherent limitations in predicting in vivo efficacy. These assays are typically performed under static, planktonic conditions and therefore do not fully replicate the complex physiological environment encountered during infection. In particular, MIC/MFC values may underestimate the antifungal concentrations required in vivo, as they do not account for host–pathogen interactions, immune responses, or pharmacokinetic factors such as absorption, distribution, and metabolism [42].

Moreover, MIC- and MFC-based assays inadequately capture the behaviour of fungal cells within structured communities. Biofilm-associated infections are characterized by altered metabolic states, restricted drug penetration, and enhanced stress tolerance, features that are not reflected in standard planktonic susceptibility testing. As a result, antifungal agents that demonstrate promising MIC/MFC values may show reduced effectiveness against biofilm-associated cells in more complex models. These limitations highlight the importance of complementing conventional antifungal assays with advanced in vitro and ex vivo models that better simulate physiological conditions and infection complexity when assessing the therapeutic potential of garlic-based formulations [43].

6. Particle Processing of Garlic Extract for Pharmaceutical Applications

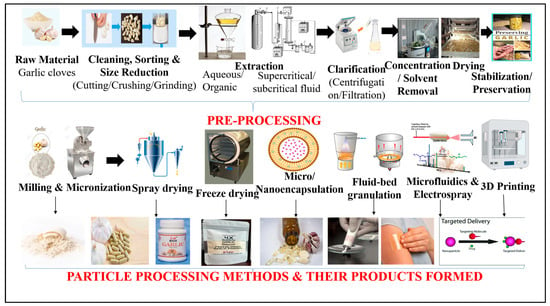

Pharmaceutical processing of garlic involves two stages: pre-processing and particle processing as shown in (Figure 5). The first stage focuses on recovery and stabilization of organosulfur compounds, whereas the second stage deals with engineering them into delivery-ready particulate forms.

Figure 5.

Workflow of Pharmaceutical Processing—Pre-Processing & Particle Processing.

6.1. Pre-Processing Stage

This stage converts raw garlic into a stable, extractable intermediate suitable for formulation. At this point, the raw garlic biomass undergoes a series of unit operations designed to maximize the yield of bioactive compounds while preventing thermal or enzymatic degradation. In the pre-processing stage, garlic cloves undergo cleaning, peeling, mechanical size reduction and enzymatic activation, followed by solvent extraction, filtration/centrifugation and extract concentration. The output from this stage serves as a feed material for particle engineering, where the extract is transformed into pharmaceutically functional particulate systems.

6.2. Unit Operations Involved

- Cleaning & Sorting: Removal of dirt and non-uniform bulbs for quality consistency.

- Size Reduction (Cutting/Crushing/Grinding)Cell rupture activates alliinase → alliin converts to allicin.

- Solvent Extraction (Aqueous/Organic)Aqueous extraction → SAC and hydrophilic compounds.Ethanolic/acetone extraction → DADS, DATS, ajoene (lipophilic actives).Modern assisted techniques: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE), MAE—Microwave-Assisted Extraction, Soxhlet, Supercritical/subcritical CO2.

During the extraction stage, the choice of solvent plays a critical role in determining both the yield and composition of garlic bioactive compounds. Polar solvents such as water and ethanol (or hydroalcoholic mixtures) are commonly employed to extract allicin, S-allyl cysteine, and other polar organosulfur compounds, owing to their high solubility in aqueous or alcoholic media. Ethanol, in particular, offers an optimal balance between extraction efficiency and reduced enzymatic degradation compared to pure aqueous systems. In contrast, non-polar solvents such as hexane or vegetable oils are primarily used to recover lipid-soluble sulfur compounds, including diallyl disulfide and diallyl trisulfide. These solvent systems not only influence extraction yield but also affect the stability, odour profile, and downstream formulation behaviour of the extract [44]. Consequently, solvent selection must be tailored to the targeted bioactive fraction and intended pharmaceutical application, highlighting its importance in garlic extract processing.

- Clarification (Centrifugation/Filtration)Removal of residual biomass → supernatant rich in volatile sulfur compounds.

- Concentration & Solvent RemovalReduced-pressure evaporation increases potency; minimizes thermal degradation.

- DryingMoisture is eliminated to convert the extract into a solid powder suitable for particle processing and formulation.

- Stabilization/PreservationpH control (≈6–7), low-temperature storage, antioxidant inclusion to slow degradation.

7. Particle Processing Stage

The second stage deals with engineering the stabilized extract into delivery-ready particulate systems. Particle-processing begins with milling and micronization, producing fine garlic powder suitable for tablet and capsule compaction. This may be followed by drying-based particle formation, such as spray drying for spherical microparticles or freeze-drying for porous reconstitutable cakes. Subsequently, nanoscale structuring via high-pressure homogenization generates nanoemulsions with improved absorption and transdermal permeability. Encapsulation systems, including coacervates and liposomes, yield micro/nano-capsules with odour shielding, improved stability and controlled release. Further downstream, fluid-bed granulation and coating convert powders into granules or pellets ideal for solid dosage fabrication. For advanced precision loading, microfluidics and electrospray produce monodisperse nano/micro-particles. Finally, next-generation dosage personalization is achieved through 3D additive manufacturing, enabling printed tablets, films and patches with programmable release behaviour. Thus, while the pre-processing safeguards and concentrates bioactives, particle processing transforms them into functional drug-delivery formats suitable for oral, topical, transdermal or inhalable formulations.

Following extraction and stabilization, garlic bioactives are transitioned into the particle-processing stage, where the goal shifts from simple recovery of organosulfur compounds to engineering them into functional particulate drug-delivery formats. As summarized in (Table 2), this involves classification of particle processing methods and (Table 3) further details the downstream unit operations within each method, highlighting how processing parameters directly influence the end product (whether micropowder, nanoparticle, granule, capsule or emulsion).

Table 2.

Classification of Particle Processing Methods.

Table 3.

Unit Operations in Particle Processing of Garlic Extract: Downstream Steps, End Products, and Applications.

7.1. Size Reduction Stage—Primary Conversion into Pharmaceutically Workable Solids

Milling & Micronization

- Dried garlic solid/extract is subjected to mechanical comminution using ball mills, jet mills or hammer mills.

- Micronization reduces particle size to 1–50 µm, increasing surface area, flowability, compressibility and dissolution rate.

- Smaller particle size enhances uniform blending in tablet/capsule formulations.

- If freeze-dried/spray-dried materials are produced later, milling may be used both before and after drying for size refinement.

- Output: Fine garlic powder.

7.2. Drying-Based Particle Formation Stage—Solid Particle Generation from Liquid Extract

7.2.1. Spray Drying

- Aqueous/ethanolic garlic extract is atomized into a hot-air chamber.

- Rapid evaporation produces spherical, free-flowing microparticles (1–100 µm).

- Supports large-scale production and encapsulation of bioactives using carriers (maltodextrin, gum arabic, cyclodextrin).

- Product: Uniform micropowder.

7.2.2. Freeze Drying (Lyophilization)

- Extract is frozen at −40 to −60 °C; ice sublimates under vacuum forming porous, sponge-like structure.

- Minimizes thermal degradation of allicin and other thiosulfinates.

- Secondary drying removes bound moisture → long shelf life, reconstitutable powder.

- Product: Highly porous freeze-dried matrix.

7.3. Nanoscale Structuring Stage—Improving Solubility, Bioavailability, Permeation

High-Pressure Homogenization/Nanoemulsification

- Garlic extract + oil + surfactant are pre-emulsified.

- Passed through homogenizer at 500–1500 bar, droplet size reduces to <200 nm.

- Surfactants stabilize droplets preventing coalescence.

- Outcome: Nanoemulsion with increased permeability and intestinal absorption.

7.4. Encapsulation & Stabilization Stage—Protection, Odour Masking, Controlled Release

Encapsulation/Liposomes/Coacervation

- Garlic extract is entrapped in polymers (chitosan, alginate) or phospholipid bilayers.

- Ionic gelation or solvent evaporation produces micro/nanocapsules.

- Liposomes mimic cell membranes enabling better penetration into microbial biofilms.

- Products: Microcapsules, nanocapsules, liposomes.

7.5. Particle Enlargement & Coating Stage—Conversion of Powders into Structured Multi-Particle Units

Fluid-Bed Granulation & Coating

- Garlic powder is fluidized in an air stream.

- Binder solution or coating polymer is sprayed, causing particles to agglomerate.

- Coating may include enteric layers, moisture-barriers or flavour masks.

- Output: Granules, coated pellets.

7.6. Precision Micro-/Nano-Particle Manufacturing Stage—Controlled Particle Size, Monodispersity, Tailored Drug-Loading

Microfluidics/Electrospray

- Garlic extract flows through microchannels or electrospray nozzle.

- Droplets form under electric field or laminar flow.

- Solvent evaporates → well-defined nano/micro spheres.

- Output: Highly monodisperse particles (50 nm–10 µm)—Targeted delivery systems, precision dosing nanoparticles.

7.7. Advanced Dosage Fabrication Stage—Transformation into Personalized Medicinal Products

3D Printing/Additive Manufacturing

- Garlic extract incorporated into printable polymer filament/ink.

- Layer-by-layer fabrication produces tablets, scaffolds or wound patches.

- Release profile is controlled digitally (slow, pulsatile, biphasic).

- Products: Printed tablets, films, patches, tissue-compatible scaffolds.

Hydrogel crosslinking strategy plays a critical role in governing both the release behaviour and stability of garlic bioactives, particularly labile organosulfur compounds such as allicin. Ionic crosslinking (Ca2+-crosslinked alginate or tripolyphosphate-crosslinked chitosan), produces physically crosslinked networks with high water content and porosity, enabling relatively rapid diffusion-controlled release, and are most suitable for highly labile compounds like allicin and ajoene. However, these hydrogels may exhibit reduced long-term stability under physiological conditions due to ion exchange and matrix relaxation. In contrast, UV-induced crosslinking generates covalently crosslinked polymer networks with higher structural integrity, improved mechanical strength, and slower, more sustained release profiles, which can better protect unstable garlic constituents from premature degradation and is therefore better suited for relatively stable sulfur compounds such as DADS and DATS, or systems where allicin is first nanoencapsulated. Thermal crosslinking further enhances matrix density and thermal stability, reducing burst release and improving the retention of encapsulated bioactives during storage. This approach favor thermally stable constituents such as SAC, while direct incorporation of allicin remains challenging due to rapid heat-induced degradation. Overall, the selection of the crosslinking method allows precise modulation of hydrogel network density, swelling behaviour, and degradation rate, thereby directly influencing garlic bioactive stability and controlled release, which are the key considerations for antifungal formulation development [64,65].

Several formulation-based studies have clearly demonstrated enhanced antifungal activity of garlic-derived systems compared to crude extracts. Garlic oil nanoemulsions prepared using high-pressure homogenization exhibited significantly lower MIC values against C. tropicalis and C. albicans than unformulated garlic extract, which was attributed to nanoscale droplet size (<200 nm), enabling improved fungal membrane disruption and intracellular delivery [66].

In another study, liposome-encapsulated allicin showed prolonged antifungal activity and superior inhibition of Candida biofilm formation compared to free allicin, owing to improved stability of the labile compound and sustained release from the phospholipid bilayer [67]. Similarly, chitosan-based garlic extract nanoparticles demonstrated enhanced antifungal efficacy and biofilm penetration, with chitosan’s positive surface charge facilitating stronger interactions with the negatively charged fungal cell wall [68].

Topical delivery systems have also benefited from formulation engineering. Chitosan–PVA hydrogels loaded with garlic nanoparticles produced sustained antifungal activity against Candida spp. and improved retention at the application site compared to aqueous garlic extract, highlighting their suitability for mucosal and cutaneous candidiasis [69]. Furthermore, spray-dried microencapsulated garlic powder using maltodextrin showed improved antifungal stability and retained activity during storage when compared with non-encapsulated extract, demonstrating the advantage of solid-state formulations [70].

These formulation-specific examples collectively demonstrate that nanoemulsions, liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, hydrogels, and spray-dried microcapsules significantly enhance the antifungal performance, stability, and delivery efficiency of garlic bioactives.

8. Conclusions

Advances in pharmaceutical processing and particle engineering have greatly enhanced the therapeutic potential of garlic extract against C. tropicalis infections, shifting it from a traditional herbal remedy to a scientifically engineered antifungal system. Modern extraction, purification, and formulation technologies now enable stabilization of sensitive actives like allicin, improved bioavailability, odour masking, and targeted delivery through nanoencapsulation, nanoemulsions, polymeric nanoparticles, liposomes, hydrogels, nanofibrous dressings, and 3D-printed matrices. Particle-engineered systems demonstrate superior penetration, sustained release, and improved antifungal performance compared to crude extracts, representing a significant technological leap.

However, translation into clinical application remains limited, with gaps in pharmacokinetics, regulatory validation, and long-term stability. The future of garlic-based antifungal therapeutics lies in establishing standardized manufacturing workflows, real-time ICH-guided stability data, advanced biofilm-targeting nanocarriers, and well-designed animal studies followed by clinical trials. Collectively, the continued integration of processing science, material engineering, and therapeutic biology positions garlic-based formulations as a strong emerging candidate in antifungal drug development, with significant potential to address rising drug resistance in C. tropicalis and broaden the scope of plant-derived therapeutics.

Author Contributions

B.S.: conceptualization, validation, visualization, supervision, review and editing; K.M.Y.: writing—original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Kavyasree Marabanahalli Yogendraiah thanks the Management of M S Ramaiah Institute of Technology for the Ramaiah Doctoral Fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| DADS | diallyl disulfide |

| DATS | diallyl trisulfide |

| SAC | S-allyl cysteine |

| ICH | International Council for Harmonisation |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MFC | Minimum Fungicidal Concentration |

| CV | Crystal violet |

| UAE | Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction |

| MAE | Microwave-Assisted Extraction |

| SC-CO2 | Supercritical Carbon Dioxide |

| RESS | Rapid Expansion of Supercritical Solutions |

| SLNs | Solid lipid nanoparticles |

| NLCs | Nanostructured lipid carriers |

| HPH | High-Pressure Homogenization |

References

- Chen, Y.C.; Dhillon, S.; Adomakoh, N.; Roberts, J.A. The Changing Epidemiology of Candida Species in Asia Pacific and Evidence for Optimizing Antifungal Dosing in Challenging Clinical Scenarios. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2025, 23, 969–983. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Fungal Priority Pathogens List to Guide Research, Development and Public Health Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: The World Health Organization (WHO) Fungal Priority Pathogens List in Response to Emerging Fungal Pathogens During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Med. Sci. Monit. 2022, 28, e939088. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, H.; Zhao, R.; Han, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jia, Z.; Wang, X. Research Progress on the Drug Resistance Mechanisms of Candida tropicalis and Future Solutions. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1594226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keighley, C.; Kim, H.Y.; Kidd, S.; Chen, S.C.-A.; Alastruey, A.; Dao, A.; Bongomin, F.; Chiller, T.; Wahyuningsih, R.; Forastiero, A.; et al. Candida tropicalis—A Systematic Review to Inform the World Health Organization of a Fungal Priority Pathogens List. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadanandan, B.; Vijayalakshmi, V.; Ashrit, P.; Babu, U.V.; Sharath Kumar, L.M.; Sampath, V.; Awaknavar, R. Aqueous Spice Extracts as Alternative Antimycotics to Control Highly Drug Resistant Extensive Biofilm Forming Clinical Isolates of Candida albicans. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281035. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Hong, H.T.; O’Hare, T.J.; Wehr, J.B.; Menzies, N.W.; Harper, S.M. A Rapid and Simplified Methodology for the Extraction and Quantification of Allicin in Garlic. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 104, 104114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Lan, X.; Cai, M.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ye, N.; Liang, X. Nineteen years retrospective analysis of epidemiology, antifungal resistance and a nomogram model for 30-day mortality in nosocomial candidemia patients. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1504866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P.; Dhiman, A.; Kumar, S.; Suhag, R. Garlic (Allium sativum L.): A Review on Bio-Functionality, Allicin’s Potency and Drying Methodologies. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 171, 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Rais, N.; Ved, A.; Ahmad, R.; Kumar, M.; Barbhai, M.D.; Chandran, D.; Lorenzo, J.M. S-Allyl-L-Cysteine—A Garlic Bioactive: Physicochemical Nature, Mechanism, Pharmacokinetics, and Health Promoting Activities. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 107, 105657. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Bai, S.; Wu, J.; Fan, Y.; Zou, Y.; Xia, Z.; Yang, R. Antifungal Activity and Potential Action Mechanism of Allicin Against Trichosporon asahii. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e00907-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maji, S.; Anand, P.; Akhter, Y. An updated account of multifaceted medicinal values of garlic: A systematic review. Curr. Tradit. Med. 2025, 11, e051023221812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, T.; Hosono, T. Functionality of garlic sulfur compounds. Biomed. Rep. 2025, 23, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yan, X.; Qiao, X.; Qiu, Z.; Zhu, W.; Lu, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, B. Evaluate the Stability of Synthesized Allicin and Its Reactivity with Endogenous Compounds in Garlic. npj Sci. Food 2025, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, D.B.; Parmar, D.K.; Sen, A.K.; Maheshwari, R.A.; Zanwar, A.S.; Joshi, K.; Koradia, S.K. Extraction and Quantification of Allicin: A Bioactive Component of Allium sativum. Pharmacogn. Res. 2025, 17, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Gwak, H.; Han, B. Advanced Manufacturing of Nanoparticle Formulations of Drugs and Biologics Using Microfluidics. Analyst 2024, 149, 614–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazár, J.; Albert, K.; Kovács, Z.; Koris, A.; Nath, A.; Bánvölgyi, S. Advances in Spray-Drying and Freeze-Drying Technologies for the Microencapsulation of Instant Tea and Herbal Powders: The Role of Wall Materials. Foods 2025, 14, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, J.; Pathania, K.; Pawar, S.V. Recent Overview of Nanotechnology-Based Approaches for Targeted Delivery of Nutraceuticals. Sustain. Food Technol. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfiyani, R.; Radjab, N.S.; Wijaya, A.N. Garlic Extract Phytosome: Preparation and Physical Stability. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2024, 16, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Korma, S.A.; Salem, H.M.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Alkafaas, S.S.; Elsalahaty, M.I.; Elkafas, S.S.; Mosa, W.F.A.; Ahmed, A.E.; et al. Garlic Bioactive Substances and Their Therapeutic Applications for Improving Human Health: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1277074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutasy, B.; Kiniczky, M.; Decsi, K.; Kálmán, N.; Hegedűs, G.; Alföldi, Z.P.; Virág, E. ‘Garlic-lipo’4Plants: Liposome-Encapsulated Garlic Extract Stimulates ABA Pathway and PR Genes in Wheat (Triticum aestivum). Plants 2023, 12, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamoto, M.; Kunimura, K.; Ohtani, M. Pharmacokinetics of sulfur-containing compounds in aged garlic extract: S-allylcysteine, S-1-propenylcysteine, S-methylcysteine, S-allylmercaptocysteine and related metabolites. Exp. Ther. Med. 2025, 29, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Mosna, K.; Orzeł, A.; Tracz, M.; Wu, S.; Krężel, A. Modification of human metallothioneins by garlic organosulfur compounds, allicin and ajoene: Direct effects on zinc homeostasis with relevance to immune regulation. BioMetals 2025, 38, 1513–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Dewali, S.; Pathak, V.M. Therapeutic role of allicin in gastrointestinal cancers: Mechanisms and safety aspects. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadanandan, B.; Vijayalakshmi, V.; Shetty, K.; Rathish, A.; Shivkumar, H.; Gundreddy, M.; Narendra, N.K.; Devaiah, N.M. In Situ Aqueous Spice Extract-Based Antifungal Lock Strategy for Salvage of Foley’s Catheter Biofouled with Candida albicans Biofilm Gel. Gels 2025, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Huang, X.; Ma, G. Antimicrobial Activities and Mechanisms of Extract and Components of Herbs in East Asia. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 29197–29213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkacz, D.; Krasowska, A. Alterations in the Level of Ergosterol in Candida albicans’ Plasma Membrane Correspond with Changes in Virulence and Result in Triggering Diversed Inflammatory Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Yu, F.; Ye, F.; Tan, W.; Hao, L.; Li, S.; Deng, J.; Hu, X. Garlic-Derived Quorum Sensing Inhibitors: A Novel Strategy Against Fungal Resistance. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 6413–6426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X. Inhibition of Efflux Pumps by Natural Compounds: Implications for Azole Resistance in Candida. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e02354-20. [Google Scholar]

- Janská, P.; Knejzlík, Z.; Perumal, A.S.; Jurok, R.; Tokárová, V.; Nicolau, D.V.; Štěpánek, F.; Kašpar, O. Effect of Physicochemical Parameters on the Stability and Activity of Garlic Alliinase and Its Use for In-Situ Allicin Synthesis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, M.; Patil, N.; Mohammed, A.; Hamzah, Z. Valorization of Garlic (Allium sativum L.) Byproducts: Bioactive Compounds, Biological Properties, and Applications. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Li, S.; Yin, Y.; Xu, W.; Xue, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F. Preparation, characterization, formation mechanism and stability of allicin-loaded emulsion gel. LWT 2022, 161, 113389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Shen, D.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Song, J. Influence of pH, concentration and light on stability of allicin in garlic (Allium sativum L.) aqueous extract as measured by UPLC. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 1838–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Saleem, M.F.; Hassanzadeh, H. Optimization of Solvent Evaporation Method in Liposomal Nanocarriers Loaded with Garlic Essential Oil (Allium sativum): Based on Encapsulation Efficiency, Antioxidant Capacity, and Instability. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 17, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushram, P.; Bose, S. Improving biological performance of 3D-printed scaffolds with garlic-extract nanoemulsions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 48955–48968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, H. Structural Characterization, Cytotoxicity, and the Antifungal Mechanism of a Novel Peptide Extracted from Garlic (Allium sativum L.). Molecules 2023, 28, 3098. [Google Scholar]

- Bhairavi, V.A.; Vidya, S.L.; Sathishkumar, R. Identification of Effective Plant Extracts Against Candidiasis: An In Silico and In Vitro Approach. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 9, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Ashrit, P.; Sadanandan, B.; Shetty, K.; Vaniyamparambath, V. Polymicrobial Biofilm Dynamics of Multidrug-Resistant Candida albicans and Ampicillin-Resistant Escherichia coli and Antimicrobial Inhibition by Aqueous Garlic Extract. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 573. [Google Scholar]

- Sadanandan, B.; Vaniyamparambath, V.; Lokesh, K.N.; Shetty, K.; Joglekar, A.P.; Ashrit, P.; Hemanth, B. Candida albicans Biofilm Formation and Growth Optimization for Functional Studies Using Response Surface Methodology. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 3277–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunanta, P.; Kontogiorgos, V.; Pankasemsuk, T.; Jantanasakulwong, K.; Rachtanapun, P.; Seesuriyachan, P.; Sommano, S.R. The Nutritional Value, Bioactive Availability and Functional Properties of Garlic and Its Related Products During Processing. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1142784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogendraiah, K.M.; Sadanandan, B.; Kyathsandra Natraj, L.; Vijayalakshmi, V.; Shetty, K. Optimization of Candida tropicalis Growth Conditions on Silicone Elastomer Material by Response Surface Methodology. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1572694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajetunmobi, O.H.; Badali, H.; Romo, J.A.; Ramage, G.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Antifungal therapy of Candida biofilms: Past, present and future. Biofilm 2023, 5, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žiemytė, M.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.C.; Ventero-Martín, M.P.; Mira, A.; Ferrer, M.D. Real-time monitoring of biofilm growth identifies andrographolide as a potent antifungal compound eradicating Candida biofilms. Biofilm 2023, 5, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, V.P.; Aazza, S.; Bertolucci, S.K.V.; Rocha, J.P.M.; Coelho, A.D.; Oliveira, A.J.M.; Dória, J. Solvent mixture optimization in the extraction of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activities from garlic (Allium sativum L.). Molecules 2021, 26, 6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar, M.; Binduga, U.E.; Szychowski, K.A. Methods of Isolation of Active Substances from Garlic (Allium sativum L.) and Its Impact on the Composition and Biological Properties of Garlic Extracts. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, B.; Qiu, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, B.; Qiao, X. Quality Improvement of Garlic Paste by Whey Protein Isolate Combined with High Hydrostatic Pressure Treatment. Foods 2023, 12, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irianto, I.; Suharmiati, S.; Zaini, A.S.; Ahmad Zaini, M.A.; Airlangga, B.; Putra, N.R. Sustainable Innovations in Garlic Extraction: A Comprehensive Review and Bibliometric Analysis of Green Extraction Methods. Green Process. Synth. 2025, 14, 20240201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Erşatır, M.; Poyraz, S.; Amangeldinova, M.; Kudrina, N.O.; Terletskaya, N.V. Green Extraction of Plant Materials Using Supercritical CO2: Insights into Methods, Analysis, and Bioactivity. Plants 2024, 13, 2295. [Google Scholar]

- Krstić, M.; Teslić, N.; Bošković, P.; Obradović, D.; Zeković, Z.; Milić, A.; Pavlić, B. Isolation of Garlic Bioactives by Pressurized Liquid and Subcritical Water Extraction. Molecules 2023, 28, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.A.; Wang, S.Y.; Wang, H.; Xiao, H.; Liu, Z.L.; Pan, Y.H.; Gao, L. Comparative Study on the Influence of Various Drying Techniques on Drying Characteristics and Physicochemical Quality of Garlic Slices. Foods 2023, 12, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.S.; Kim, M.K. Determination of Aroma Characteristics of Commercial Garlic Powders Distributed in Korea via Instrumental and Descriptive Sensory Analyses. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 27, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, L.; Santos, L.; Noreña, C.P.Z. Bioactive Compounds of Garlic: A Comprehensive Review of Encapsulation Technologies, Characterization of the Encapsulated Garlic Compounds and Their Industrial Applicability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Tang, J.; Xu, M. Synergistic Stabilization of Garlic Essential Oil Nanoemulsions by Carboxymethyl Chitosan/Tween 80 and Application for Coating Preservation of Chilled Fresh Pork. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dana, P.; Yostawonkul, J.; Chonniyom, W.; Unger, O.; Sakulwech, S.; Sathornsumetee, S.; Saengkrit, N. Nanostructured Lipid-Based Carrier for Specific Delivery of Garlic Oil through the Blood–Brain Barrier Against Glioma Aggressiveness. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 64, 102651. [Google Scholar]

- Laina, K.T.; Drosou, C.; Krokida, M. Comparative Assessment of Encapsulated Essential Oils through Innovative Electrohydrodynamic Processing and Conventional Spray- and Freeze-Drying Techniques. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 95, 103720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Pan, Y.; Feng, M.; Guo, W.; Fan, X.; Feng, L.; Cao, Y. Garlic Essential Oil-in-Water Nanoemulsion Prepared by High-Power Ultrasound: Properties, Stability and Antibacterial Mechanism Against MRSA Isolated from Pork. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 90, 106201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, H.; Rahbari, M.; Galali, Y.; Hosseini, M.; Ghanbarzadeh, B. Garlic Extract-Loaded Nanoemulsion: Physicochemical, Rheological and Antimicrobial Properties with Application in Mayonnaise. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 3799–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaraliyeva, A.; Turgumbayeva, A.; Kartbayeva, E.; Kalykova, A.; Mombekov, S.; Akhelova, A.; Bekesheva, K. GC–MS Based Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity of Garlic CO2 Subcritical Extract (Allium sativum). Amino Acids 2024, 72, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lemar, K.M.; Turner, M.P.; Lloyd, D. Garlic (Allium sativum) as an Anti-Candida Agent: A Comparison of the Efficacy of Fresh Garlic and Freeze-Dried Extracts. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 93, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fojlaley, M.; Kalkan, F.; Ranji, A. Drying Process of Garlic and Allicin Potential—A Review. World J. Environ. Biosci. 2020, 9, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, S.R.; Gofur, A.; Hartatiek, D.; Annisa, Y.; Ramadhani, D.N.; Rahma, A.N.; Aisyah, D.N.; Mufidah, I.N.; Rifqi, N.D. Characterization and In-Vitro Study of Micro-Encapsulation Chitosan-Alginate of Single-Bulb Garlic Extract. Pharm. Nanotechnol. 2024, 12, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadaga, A.K.; Gudla, S.S.; Nareboina, G.S.K.; Gubbala, H.; Golla, B. Comprehensive Review on Modern Techniques of Granulation in Pharmaceutical Solid Dosage Forms. Intell. Pharm. 2024, 2, 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Wu, S.; Ning, M. 3D Printing for Controlled Release Pharmaceuticals: Current Trends and Future Directions. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 669, 125089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, K.; Rajankar, N.; Aalhate, M.; Mahajan, S.; Maji, I.; Gupta, U.; Singh, P.K. Hydrogels as delivery systems in herbal medicine. In Formulating Pharma-, Nutra-, and Cosmeceutical Products from Herbal Substances: Dosage Forms and Delivery Systems; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 323–353. [Google Scholar]

- Azam, F.; Anwar, M.J.; Kahfi, J.; Almahmoud, S.A.; Emwas, A.H. Cracking the sulfur code: Garlic bioactive molecules as multi-target blueprints for drug discovery. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, A.R.; Borse, S.L. A comprehensive review on garlic oil as an anti-inflammatory nanoemulsion. Curr. Nanomed. 2025, 15, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmowafy, E.; El-Marakby, E.M.; Gad, H.A.; Gad, H.A. Delivery systems of plant-derived antimicrobials. In Promising Antimicrobials from Natural Products; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 397–442. [Google Scholar]

- Kotenkova, E.; Kotov, A.; Nikitin, M. Polysaccharide-based nanocarriers for natural antimicrobials: A review. Polymers 2025, 17, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masood, F.; Makhdoom, M.A.; Channa, I.A.; Gilani, S.J.; Khan, A.; Hussain, R.; Rehman, M.A.U. Development and characterization of chitosan- and chondroitin sulfate-based hydrogels enriched with garlic extract for potential wound healing and skin regeneration applications. Gels 2022, 8, 676. [Google Scholar]

- Wijayanti, N.; Widyaningsih, T.D.; Wulan, S.N.; Rifai, M. Influence of spray drying inlet temperature on the physical properties and antioxidant activity of black garlic extract powder. Trends Sci. 2024, 21, 7247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).