Abstract

This paper presents the results of experimental research focused on the production of a cement composite in which natural aggregate was entirely replaced by recycled glass recovered from photovoltaic panels. The resulting cement composites were subjected to measurements of their physical and mechanical properties, followed by surface treatment (polishing) carried out under both laboratory and industrial conditions. Surface image analysis showed that the selected polishing process enabled the creation of a uniformly treated surface without compromising the internal structure of the innovative composite.

1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of photovoltaic (PV) panel use, which began in the 1990s, has brought with it the need to address the recycling of these systems once they reach the end of their life cycle, typically estimated at 25 to 30 years [1,2]. Since the glass from PV panels is a non-biodegradable material, its disposal in landfills poses an environmental concern, particularly in terms of limited storage capacity [3]. In line with the growing emphasis on sustainability and the circular economy, increasing efforts are being made to develop effective recycling methods for the various components of PV panels. These include not only aluminum but also glass, plastics, photovoltaic cells, heavy metals, and rare elements such as silver, tellurium, indium, gallium, and molybdenum [4,5,6].

However, the glass from photovoltaic panels is not suitable for reuse in traditional glassmaking, as it may contain impurities that could contaminate raw materials and compromise the quality of final products [7]. As a result, alternative applications are being explored, especially in the construction industry. One well-established method involves incorporating recycled glass into cement matrices as a substitute for natural aggregate, contributing to the reduction in primary raw material consumption [8,9,10,11]. Another promising approach is the use of finely ground glass powder as a partial replacement for Portland cement—typically between 10% and 30%—which can enhance the mechanical properties of the composite while simultaneously reducing CO2 emissions associated with cement production [12].

Further research indicates that crushed glass can effectively replace natural aggregate, as it demonstrates good adhesion with the cement paste and does not negatively affect the workability of the mixture [13]. Additionally, when finely ground waste glass from PV panels is used, improvements in the strength of cement composites have been observed, suggesting partial pozzolanic activity of the material [14].

There are also other studies focused on the utilization of industrial waste materials—such as waste cellulose fibers, rigid polyurethane foam at the end of its life cycle, and waste calcium silicates from production processes—as secondary raw materials for the development of unconventional cement composites based on these components [15,16,17,18].

In this study, recycled glass material originating from photovoltaic panels was used as a 100% replacement for natural aggregate in the production of a cement-based composite. The aim was to evaluate its physical and mechanical properties and to assess the potential for surface finishing of the final material for application in the construction industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the Cement-Based Composite

Portland cement CEM I 52.5 R (Cement Hranice, a.s., Bělotínská 288, 753 01 Hranice I-Město, Czech Republic) and tap water from the public water supply system were used to produce the cement composites. As a replacement for natural aggregate, recycled glass material sourced from end-of-life photovoltaic panels (denoted as GR) was supplied by Bambas Elektroodpady s.r.o. The material was sorted into the following particle size fractions: 0–0.5 mm, 0.5–1 mm, 1–4 mm, and 4–10 mm.

To improve the workability of the fresh mix and to reduce the water-to-cement ratio, a plasticizing admixture, MasterGlenium SKY 980 (Master Builders Solutions CZ s.r.o., Czech Republic), was added. For coloring purposes, pigments were incorporated into the mix—specifically blue CB840, white R200M, green G820, and black B630 (PRECHEZA a.s., Czech Republic). The mix design is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recipe for the preparation of cement composites.

The fresh composite was poured into steel molds to produce prismatic test specimens (40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm) and into wooden molds for tile specimens (400 mm × 400 mm × 30 mm). The prisms were cured in a water bath for 28 days, while the tile specimens were kept under laboratory conditions (20 °C) and subsequently subjected to a surface finishing process (polishing).

2.2. Mechanical Properties

Table 2 presents the results of flexural and compressive strength tests performed on prismatic specimens cured in water for 2, 7, 28, 90, and 180 days. The highest values of flexural and compressive strength were recorded after 28 days of curing.

Table 2.

Flexural and compressive strengths.

2.3. Bulk Density Measurement of Glass Fractions

The bulk density of the recycled glass (including particles smaller than 0.063 mm) was determined according to the ČSN EN 1097-6 standard [19]. The results are summarized in Table 3. The measured bulk density values of individual fractions ranged between 2.47 and 2.51 Mg/m3.

Table 3.

Bulk density of recycled glass grains.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Laboratory Polishing

Specimens measuring 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm were cut using a Struers (Copenhagen, Denmark) Discoplan-TS diamond blade with continuous water cooling. This method produced clean cuts, free of dust and thermal degradation in the cutting zone. Surface finishing was performed in accordance with standards for petrographic analysis [20,21]. The procedure involved sequential grinding of the samples using abrasive papers with grit sizes of 220, followed by 400 and 800, and finally polishing with a cloth and a white polishing paste containing 2% aluminum oxide. (See Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Sanding of cement composite on sandpaper with a grain size of 400.

Figure 2.

Polishing of cement composite with white polishing paste.

3.2. Industrial Polishing

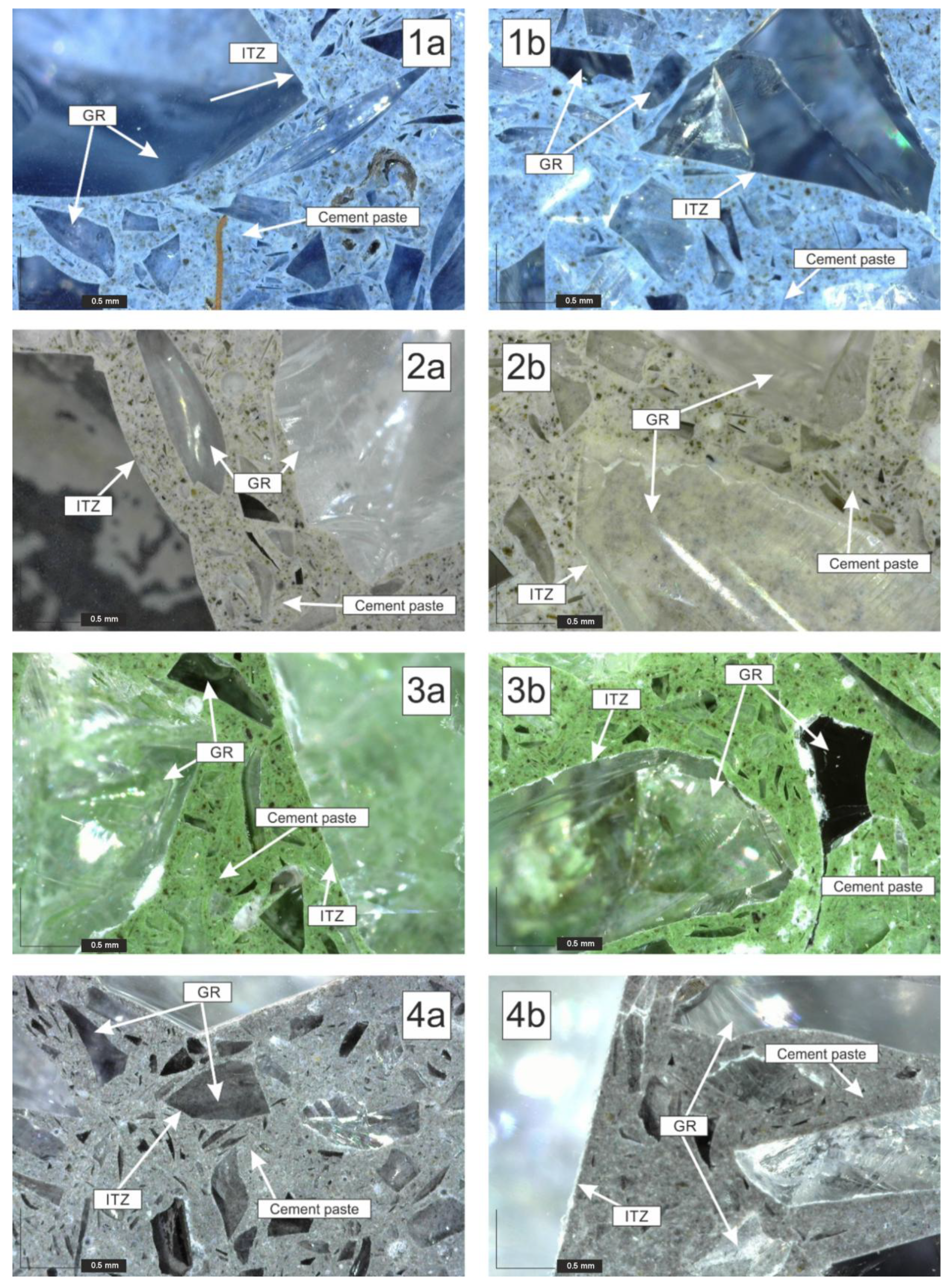

In the industrial setting, the surface finishing process was carried out in a custom-designed polishing chamber. Samples were placed into a box equipped with four abrasive belts and one stone polishing plate. To ensure uniform hardness during processing, each sample was wrapped in plastic and embedded in a gypsum mixture of medium to fast setting consistency (setting time: 24–48 h). After demolding, the sample was fixed between polishing arms that ensured a planar surface. The polishing process employed diamond discs with grit sizes ranging from 30 to 3000, using abrasives supplied by various manufacturers [22]. (See Figure 3 and Figure 4 for examples of polished samples containing different pigments.)

Figure 3.

(a) Original sample; (b) ground sample; (c) polished sample.

Figure 4.

(1a–4a) Samples polished by Technistone s.r.o. Company (Hradec Králové, Czech Republic); (1b–4b) samples polished in laboratory conditions (GR—recycled glass; ITZ—contact zone between recycled glass grains and cement paste).

The comparison of laboratory and industrial surface finishing confirmed that both methods can achieve a uniform and defect-free surface texture. This finding is consistent with the results of Park et al. [13], who reported that recycled glass aggregate shows good bonding properties with the cement paste, enabling the formation of compact and visually homogeneous composites. Similarly, Saccani and Bignozzi [8] demonstrated that fine glass fractions, when adequately treated, do not induce harmful alkali–silica reactions (ASR) and maintain the mechanical integrity of the material after surface processing.

3.3. Comparison of Methods

Surface image analysis conducted with a USB microscope (Dino-Lite Premier Digital Microscope AM4113ZT, AnMo Electronics Corporation, Tchaj-pej, Taiwan) revealed that both polishing techniques—laboratory and industrial—produced a comparable surface finish without noticeable defects. The primary difference lay in the treated surface area: the laboratory method processed a smaller surface (1600 mm2), whereas the industrial method could polish much larger areas (160,000 mm2).

From a microstructural perspective, the smooth surface and well-defined interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the glass particles and the cement paste (Figure 4) support the conclusions of Ludvík et al. [22], who emphasized the importance of aggregate petrography in the development of composite microstructure. Moreover, the use of PV glass fractions with particle densities of 2.47–2.51 Mg/m3 is advantageous because it is close to that of natural siliceous aggregates, ensuring good particle packing and minimal segregation.

4. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to compare the polishing outcomes of a cement-based composite in which 100% of the natural aggregate was replaced with recycled glass sourced from photovoltaic panels, processed under both laboratory and industrial conditions. Based on the surface image analysis, it can be concluded that both approaches yield comparable results without significant defects or differences in surface quality. The experiment confirmed that recycled glass can be effectively incorporated into a cement matrix and subsequently subjected to surface finishing without compromising the integrity of the composite structure. From a practical perspective, the developed material shows great potential for use in architectural and interior applications, particularly where a polished and aesthetically appealing surface is required. These include decorative floor tiles, façade panels, terrazzo-like pavements, countertops, and cladding elements. Due to its high surface hardness and visual appearance comparable to natural stone, the composite can also be used for urban furniture or prefabricated façade components. Moreover, the utilization of end-of-life photovoltaic glass contributes to reducing landfill waste, conserving natural aggregate resources, and promoting circular manufacturing principles within the construction industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M.; methodology, K.M.; investigation, K.M. and T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M. and T.K.; writing—review and editing, K.M.; visualization, K.M. and T.K.; supervision, K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chowdhury, M.S.; Applasamy, S.; Yusup, S.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Techno-economic review of solar photovoltaic systems: Case study of a PV-powered community microgrid in Malaysia. Energy Strategy Rev. 2020, 27, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padoan, F.C.S.M.; Byrne, J.; Reinders, A. A review of PV shading effects. Sol. Energy 2019, 177, 746–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.; Benveniste, G.; Sharma, A.; Apul, D.S. Waste from solar photovoltaic panels: A literature review. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2020, 4, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aman, M.M.; Jasmon, G.B.; Bakar, A.H.; Mokhlis, H.; Bakar, A. Analysis of the performance of grid-connected solar PV systems in Malaysia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 1190–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Tokoro, C.; Yamazaki, S.; Ogata, Y. Recycling technology of waste photovoltaic panels for sustainable resource utilization. Adv. Powder Technol. 2021, 32, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckend, S.; Wade, A.; Heath, G. End-of-Life Management: Solar Photovoltaic Panels; International Energy Agency (IEA): Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bajer, T. Possibilities of Using Recycled Glass from Photovoltaic Panels in Construction. Master’s Thesis, Brno University of Technology, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Brno, Czech Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saccani, A.; Bignozzi, M.C. ASR expansion behavior of recycled glass fine aggregates in concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagnit-Hamou, A.; Tagnit-Hamou, A.; Ait-Mokhtar, A. Use of recycled glass in concrete: A review. Concr. Int. 2015, 39, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili, J.; Oudah AL-Mwanes, A. Recycled glass aggregate as a partial replacement for fine aggregate in concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 42, 1958–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latunussa, C.E.L.; Ardente, F.; Blengini, G.A.; Mancini, L. Life Cycle Assessment of an innovative recycling process for crystalline silicon photovoltaic panels. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 156, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabdo, A.A.; Abd Elmoaty, M.A.; Aboshama, A.Y. Utilization of waste glass powder in the production of cement and concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 124, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.B.; Lee, B.C.; Kim, J.H. Studies on mechanical properties of concrete containing waste glass aggregate. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 2181–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Habert, G.; Bouzidi, Y.; Jullien, A. Environmental impact of cement production: Detail of the different processes and cement plant variability evaluation. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 18, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Václavík, V.; Valíček, J.; Dvorský, T.; Hryniewicz, T.; Kušnerová, M.; Daxner, J.; Bendová, M. A Method of Utilization of Polyurethane after the End of Its Life Cycle. Rocz. Ochr. Sr. 2012, 14, 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Števulová, N.; Hospodárová, V.; Václavík, V.; Dvorský, T.; Danek, T. Characterization of Cement Composites Based on Recycled Cellulosic Waste Paper Fibres. Open Eng. 2018, 8, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Břenek, A.; Václavík, V.; Dvorský, T.; Daxner, J.; Dirner, V.; Bendová, M.; Harničárová, M.; Valíček, J. Capillary Active Insulations Based on Waste Calcium Silicates. In Mechanical and Materials Engineering of Modern Structure and Component Design; Głowacki, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Václavík, V.; Daxner, J.; Valíček, J.; Dvorský, T.; Kušnerová, M.; Harničárová, M.; Bendová, M.; Břenek, A. The Use of Industrial Waste as a Secondary Raw Material in Restoration Plaster with Thermal Insulating Effect. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 897, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ČSN EN 1097-6; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates—Part 6: Determination of Particle Density and Water Absorption. Czech Standards Institute: Prague, Czech Republic, 2013.

- EN 12326-2; Slate and Stone Products for Discontinuous Roofing and Cladding—Part 2: Methods of Test. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- EN 12407; Natural Stone Test Methods—Petrographic Examination. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2007.

- Ludvík, J.; Dobeš, P.; Kužvart, M. Petrographic assessment of aggregate in terms of influence on microstructure development of cement composites. Minerál 2020, 6, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).