Abstract

At present, a wide range of commercial resins is available for diverse applications, whether in both the food and industrial sector. However, limited information is available in the literature to scientifically evaluate the effectiveness and behaviour of new commercial resins under varying application conditions. In this study, the Purolite MB400 ion-exchange resin was investigated for its capacity to simultaneously remove metal cations (Cu, Zn, Fe) and sulphates from model solutions. The highest efficiency was observed in the CuSO4 model solution (10 mg/L), where Cu2+ removal reached 97.8% and SO42− removal 95.1%. However, increasing concentrations of metals and sulphates resulted in a gradual decline in removal efficiency.

1. Introduction

Surface waters, including rivers, lakes, and streams, are vital resources for ecosystems and human activities. However, these water bodies are increasingly exposed to contamination from a variety of pollutants, with heavy metals and sulphates being of particular concern [1]. Although some heavy metals are essential in trace amounts for biological processes, elevated concentrations in surface waters pose serious environmental and health risks [2]. Heavy metals are not biodegradable and therefore tend to bioaccumulate in living organisms. They are also persistent and can directly or indirectly impact various species through biomagnification. Moreover, many heavy metal ions are toxic or carcinogenic [3,4].

Mining represents a key sector of economic activity, playing a central role in both developed and developing countries. However, this industry is also a major source of heavy metal contamination, as mineral extraction releases significant quantities of metals that are subsequently transported through rivers and streams, either dissolved in water or bound to sediments. These metal species can infiltrate groundwater, contributing to water scarcity, hindering crop growth through soil degradation, and posing serious health risks to animals and local human populations [5].

Sulphates, on the other hand are naturally present in the environment, often as a consequence of mineral weathering. Sulphur is an essential nutrient for living organisms; thus, sulphate is a common nutrient, and sulphate therefore occurs commonly as a nutrient in both natural waters and wastewaters [6]. Its concentration varies according to location for example, in rivers from 0 to 630 mg/L, in lakes from 2 to 250 mg/L, in groundwater from 0 to 230 mg/L, in seawater up to 2700 mg/L and in rain water 1–6 mg/L [7]. However, anthropogenic activities such as industrial discharges, mining, and agricultural runoff can significantly increase sulphate concentrations in surface waters. Elevated sulphate levels may cause acidification of water bodies, with harmful effect on aquatic life, alterations in water chemistry, and increased solubility of toxic metals [8].

To mitigate the environmental and health risks posed by heavy metals and sulphates in surface waters, a variety of treatment technologies have been developed, among which ion exchange resins have proven particularly effective. Compared with other conventional methods, ion exchange offers distinct advantages. This method allows for the effective removal of nearly all ionic species from a solution or substances [9]. Ion exchange resins are synthetic polymers capable of exchanging specific ions in a solution with those bound to the resin. These resins can selectively remove heavy metals and sulphates from contaminated water by replacing them with less harmful ions, such as sodium or chloride, present on the resin [10,11]. Ion-exchange resins can therefore be classified into those designed for the selective removal of specific ions from contaminated water and those intended for the complete deionization of wastewater. The choice between these types depends primarily on the composition of the solution and the required extent of decontamination. Selectivity is achieved through the use of specific ion exchangers with a high affinity for particular metal ions or groups of metals. In most cases, ion exchange involves replacing undesirable ions with others that are non-toxic to aquatic systems [4]. This process is highly efficient, offering the advantages such as a high removal capacity, reusability of the resin, and the ability to target specific contaminants. Ion exchange resins are widely used in water treatment plants and in industrial applications to purify surface waters and ensure compliance with environmental standards [12,13].

Understanding the sources, pathways, and effects of heavy metals and sulphates in surface waters, along with effective removal methods such as ion exchange resins, is essential for developing comprehensive strategies to protect aquatic ecosystems and ensure water quality for human use.

The aim of this paper is to investigate the efficiency of Purolite MB400 ion-exchange resin in removing SO42− and selected metal cations from model solutions.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Ion Exchange Resin Characterisation

The ion-exchange resin Purolite MB400, supplied by a commercial distributor in Slovakia, was applied in static adsorption experiments. This material is a mixed-bed ion-exchange resin of high quality, primarily intended for water purification processes. It can be used in both regenerable and non-regenerable cartridges, as well as in large-scale ion-exchange installations. The resin is composed of approximately 40% cation-exchange (Catex) and 60% anion-exchange (Anex) components, providing a balanced ion mixture. Purolite MB400 was originally developed for the production of high-purity water, with about 97% of its particles having a diameter below 0.3 mm. In addition, it is widely applied for the preparation of demineralized water, free of carbon dioxide and silica impurities.

2.2. Synthetic Solutions

Stock solutions of copper, zinc, and iron (1000 mg/L) were prepared by dissolving the corresponding sulphate salts (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in distilled water. Lower concentrations of metals (10, 50, 100, 200, and 300 mg/L) and the appropriate amounts of sulphates were obtained by diluting the stock solutions with distilled water.

2.3. Sorption Experiments

A sample of 1 g of resin was added to 100 mL of each prepared model solution and maintained at laboratory temperature (20 ± 1 °C). The adsorption tests were carried out in a batch system under static conditions, with a contact time of 24 h. After the interaction period, the resin was separated by filtration. The remaining concentrations of sulphates and metals were determined using a colorimetric technique (Colorimeter DR 890, HACH Company, Loveland, CO, USA). The pH values of the solutions were measured with a pH metre (inoLab pH 730, WTW, Weilheim, Germany). All adsorption experiments were conducted in triplicate under batch conditions, and the obtained results are expressed as arithmetic mean values.

3. Results and Discussion

Purolite MB400 ion exchange resin was used in this experiment to determine the efficiency of removing SO42− and heavy metal ions from model solutions.

Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 present the results of batch adsorption experiments for the removal of Zn2+, Cu2+, and Fe2+, along with SO42−, using Purolite MB400 resin after 24 h of contact. Initial concentrations (Input) and residual concentrations (after 24 h) are shown for each ion. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the values are reported as arithmetic means.

Table 1.

Initial concentration of Zn2+ and SO42− and concentration after 24 h of contact time with PUROLITE MB400 resin; ZnSO4 solution; dosage 1 g/100 mL.

Table 2.

Initial concentration of Cu2+ and SO42− and concentration after 24 h of contact time with PUROLITE MB400 resin; CuSO4 solution; dosage 1 g/100 mL.

Table 3.

Initial concentration of Fe2+ and SO42− and concentration after 24 h of contact time with PUROLITE MB400 resin; FeSO4 solution; dosage 1 g/100 mL.

The data demonstrate that Purolite MB400 resin effectively reduced the concentrations of both metal cations and sulphates across all tested initial levels. At the lowest concentrations, removal was nearly complete, with residual metal and sulphate concentrations approaching minimal values (e.g., Zn2+ 0.3 mg/L, Cu2+ <0.05 mg/L, Fe2+ 0.5 mg/L; SO42− 0.8–1.4 mg/L). As the initial concentrations increased, the absolute amounts of ions removed also increased; however, the residual concentrations after 24 h were higher, reflecting a decrease in relative removal efficiency at elevated concentrations.

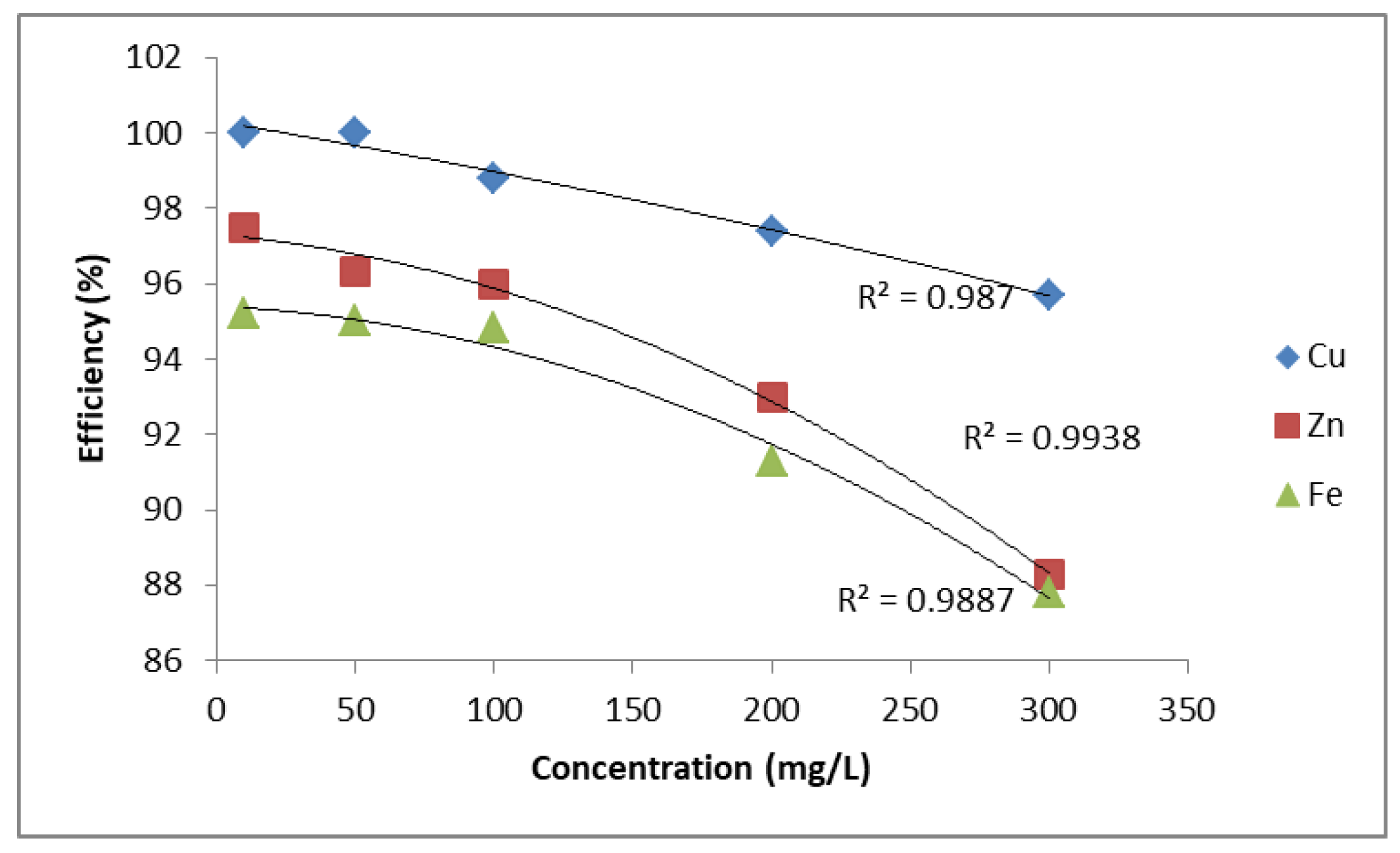

A comparison of removal efficiency is shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Figure 1 shows the relationship between ion concentration (mg/L) and removal efficiency (%) for Cu2+, Zn2+, and Fe2+. The efficiency decreases with increasing concentration for all three metal ions. Among them, Cu2+ demonstrates the highest removal efficiency, remaining above 95% even at higher concentrations, with a linear regression fit (R2 = 0.987). Zn2+ and Fe2+ show slightly lower efficiencies, both following polynomial regression trends with high correlation values (R2 = 0.9938 for Zn2+ and R2 = 0.9887 for Fe2+). Overall, PUROLITE MB400 is more effective in removing Cu2+ compared to Zn2+ and Fe2+.

Figure 1.

Removal efficiency of Zn2+, Cu2+, and Fe2+ using PUROLITE MB400.

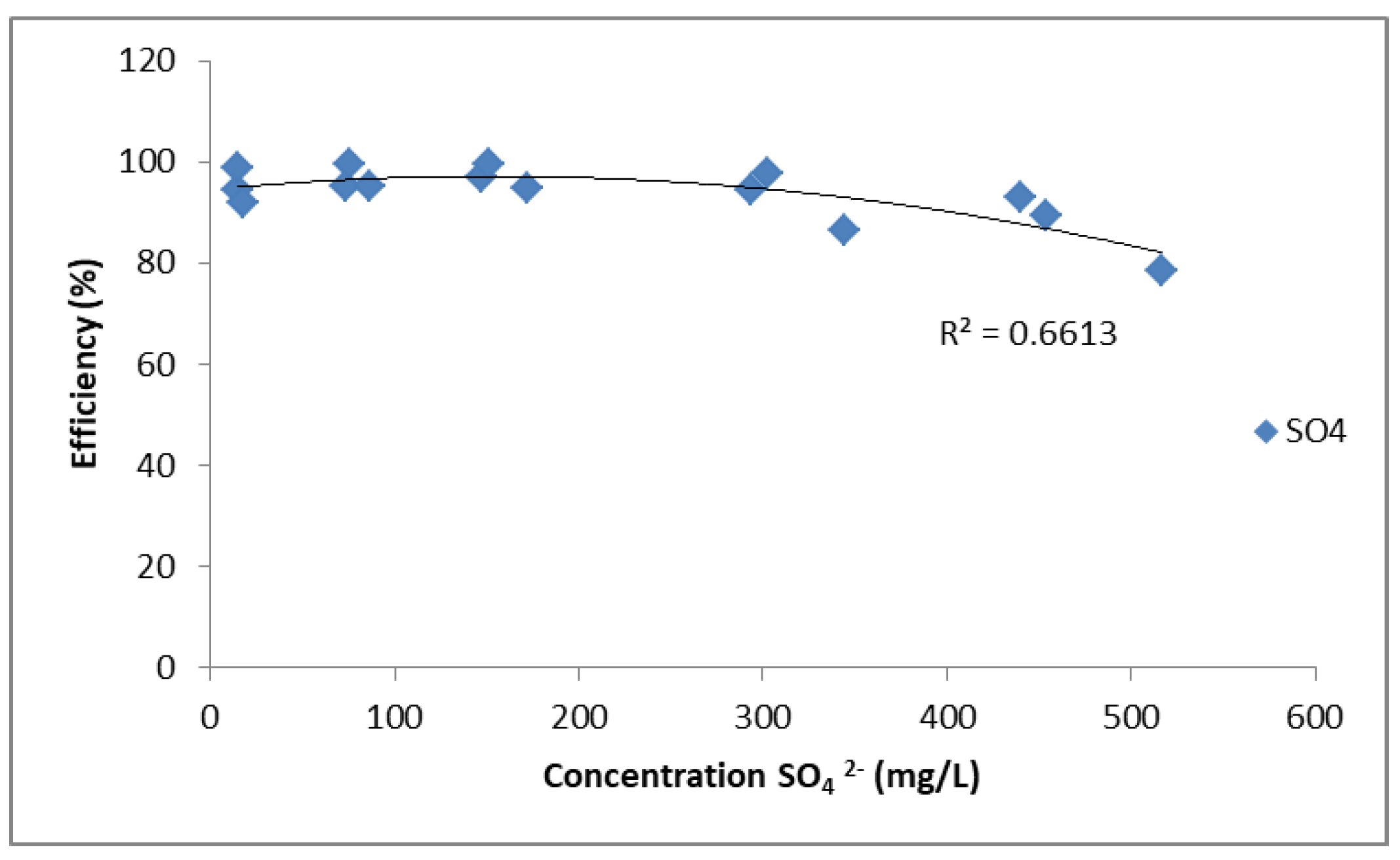

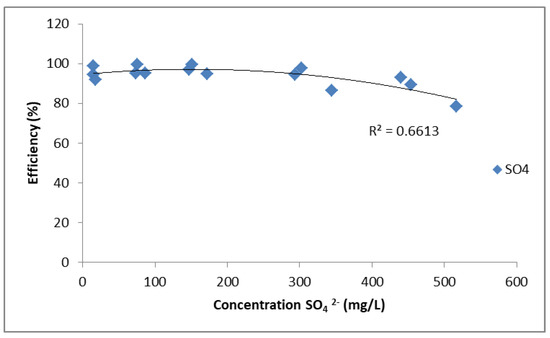

Figure 2.

Removal efficiency of SO42− using PUROLITE MB400.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between SO42− ion concentration (mg/L) and removal efficiency (%), obtained from CuSO4, ZnSO4, and FeSO4 solutions. The removal efficiency remains high, close to 95–100%, at lower concentrations but shows a gradual decrease as the SO42− concentration increases beyond 300 mg/L, reaching around 80% at 500 mg/L. The fitted curve has a correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.6613, indicating moderate agreement with the experimental data. Overall, PUROLITE MB400 demonstrates high efficiency in removing sulphate ions, although efficiency slightly decreases at higher concentrations.

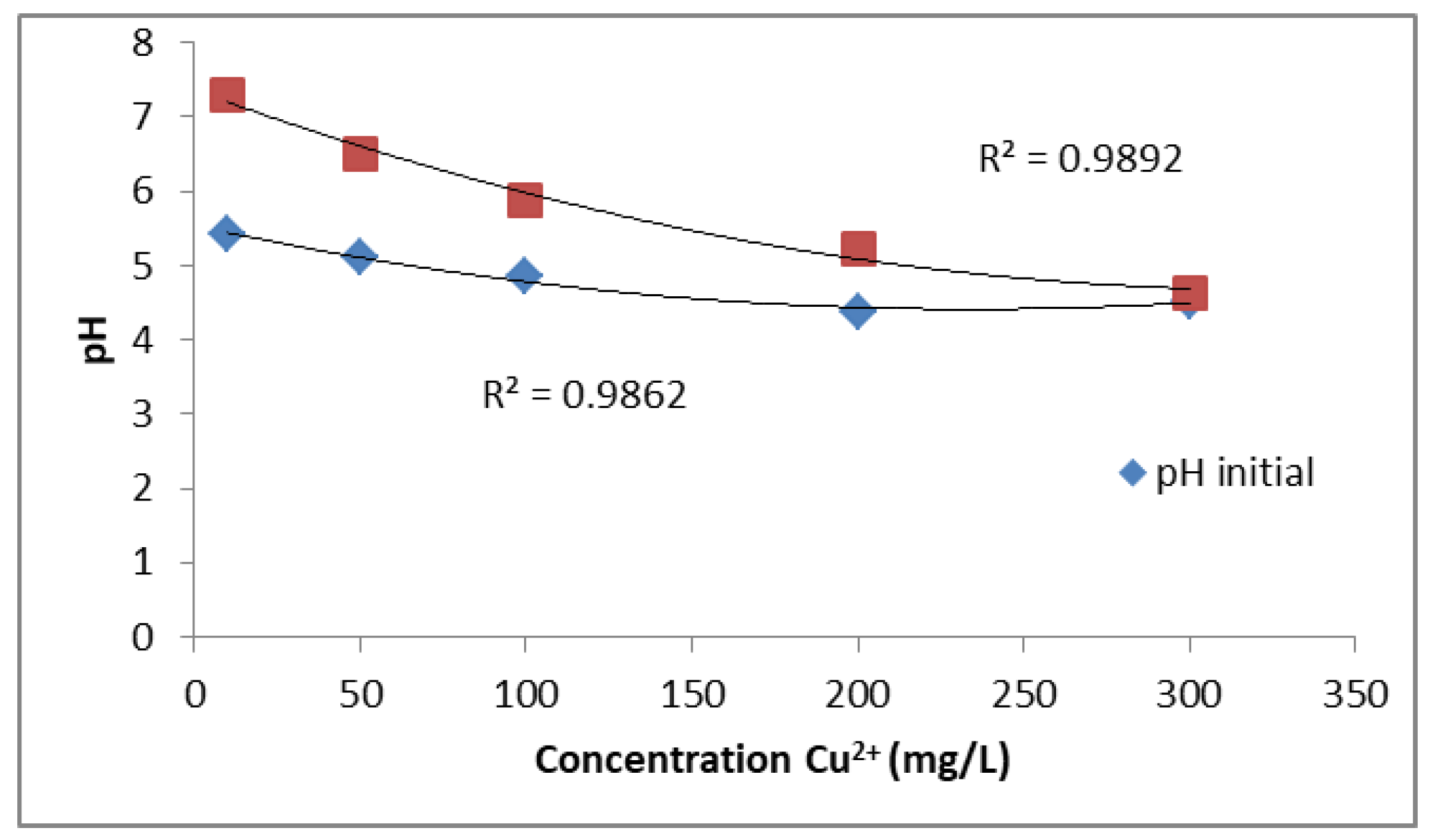

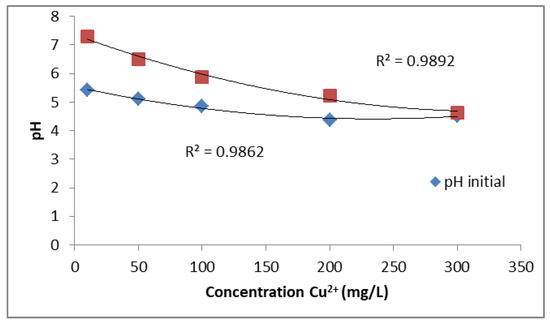

The pH is one of the key parameters influencing the adsorption of sulphates and heavy metals from aqueous solutions. In this study, the initial pH of the solutions was not adjusted prior to the experiments. However, after the ion exchange process with PUROLITE MB400, the pH values of the solutions consistently increased. As shown in Figure 3, the initial pH decreases gradually with increasing Cu2+ concentration, ranging from about 5.5 at low concentrations to below 4.5 at higher concentrations. After ion exchange, the final pH values are notably higher, especially at lower Cu2+ concentrations, but also follow a decreasing trend with increasing metal ion concentration. The fitted curves show strong correlations (R2 = 0.9862 for initial pH and R2 = 0.9892 for final pH). These results confirm that the ion exchange process contributes to a measurable increase in solution pH across all tested concentrations.

Figure 3.

Effect of ion exchange on the pH of CuSO4 solution at different Cu2+ concentrations.

4. Conclusions

Ion exchange represents a widely applied method for the removal of pollutants from wastewater, owing to its high treatment capacity, efficiency, and rapid kinetics. The present study demonstrated the applicability of Purolite MB400 ion exchange resin for the removal of sulphates and selected cations (Zn, Cu, Fe) from model solutions. The experimental results confirmed that the resin exhibits the following order of affinity for the investigated cations: Cu2+ > Zn2+ > Fe2+. The highest performance was achieved for the CuSO4 model solution (10 mg/L), where the removal efficiency reached 97.8% for Cu2+ and 95.1% for SO42−. Nevertheless, a decrease in efficiency was observed with increasing concentrations of metals and sulphates.

These findings suggest that ion exchange may be considered a suitable treatment option for water contaminated with sulphates and heavy metals, given its operational simplicity, high efficiency, selectivity, and comparatively low operating costs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and N.J.; methodology, M.B.; validation, A.E. and A.L.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, A.E.; resources, N.J.; data curation, A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, N.J. and A.E.; supervision, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic, projects VEGA Grant No. 1/0286/25 and VEGA Grant No. 2/0108/23.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Carolin, C.F.; Kumar, P.S.; Saravanan, A.; Joshiba, G.J.; Naushad, M. Efficient techniques for the removal of toxic heavy metals from aquatic environment: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2782–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Ledezma, C.; Negrete-Bolagay, D.; Figueroa, F.; Zamora-Ledezma, E.; Ni, M.; Alexis, F.; Guerrero, V.H. Heavy metal water pollution: A fresh look about hazards, novel and conventional remediation methods. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 22, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Cabral-Pinto, M.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, M.; Dinis, P.A. Estimation of risk to the eco-environment and human health of using heavy metals in the Uttarakhand Himalaya, India. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Wang, Q. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birn, A.E.A.; Shipton, L.; Schrecker, T.; Shipton, L. Canadian mining and ill health in Latin America: A call to action. Can. J. Public Health 2018, 109, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zak, D.; Hupfer, M.; Cabezas, A.; Jurasinski, G.; Audet, J.; Kleeberg, A.; McInnes, R.; Kristiansen, S.M.; Petersen, R.J.; Liu, H.; et al. Sulphate in freshwater ecosystems: A review of sources, biogeochemical cycles, ecotoxicological effects and bioremediation. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 212, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runtti, H.; Tolonen, E.T.; Tuomikoski, S.; Luukkonen, T.; Lassi, U. How to tackle the stringent sulfate removal requirements in mine water treatment—A review of potential methods. Environ. Res. 2018, 167, 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Chatla, A.; Almanassra, I.W.; Abushawish, A.; Laoui, T.; Alawadhi, H.; Atieh, M.A.; Ghaffour, N. Sulphate removal from aqueous solutions: State-of-the-art technologies and future research trends. Desalination 2023, 558, 116515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowski, A.; Hubicki, Z.; Podkościelny, P.; Robens, E. Selective removal of the heavy metal ions from waters and industrial wastewaters by ion-exchange method. Chemosphere 2004, 56, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, Y.; Ekmeci, Z. Removal of sulfate ions from process water by ion exchange resins. Miner. Eng. 2020, 159, 106613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benalla, S.; Addar, F.Z.; Tahaikt, M.; Elmidaoui, A.; Taky, M. Heavy metals removal by ion-exchange resin: Experimentation and optimization by custom designs. Desalin. Water Treat. 2022, 262, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyabrata, P.; Banat, F. Comparison of heavy metal ions removal from industrial lean amine solvent using ion exchange resins and sand coated with chitosan. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2014, 18, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demcak, S.; Balintova, M.; Holub, M. The removal of sulphate ions from model solutions and their influence on ion exchange resins. Econ. Environ. 2020, 73, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).