Abstract

This article deals with legislative and environmental safety gaps in tailings management facilities handling within the Czech Republic and the EU (European Union). Through analysis of regulatory frameworks, incidents and old environmental burdens, it highlights deficiencies, aiming to bolster the effective management of environmental risks and improve the lack of information, transparency and cross-border cooperation.

1. Introduction to Tailing Management Facilities Issues

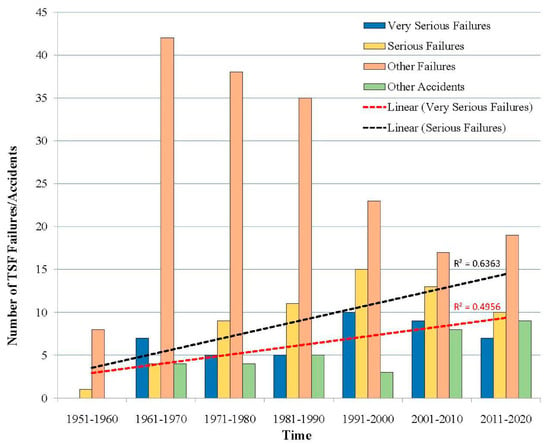

Tailing management facilities (TMFs) are dam-like structures engineered to contain tailing particles—“fine-grained waste material remaining after the metals and minerals recoverable with the technical processes applied have been extracted” [1]. Despite their intended purpose, the presence of these often-massive structures poses significant risks to surrounding environments due to the potential for long-term (often accidental) environmental contamination. Numerous incidents have been reported in which TMF failures have resulted in immediate and devastating impacts, including the loss of human life [2]. For instance, the Stava disaster led to the deaths of 268 individuals and the destruction of 56 houses and six industrial buildings, exemplifying the severe consequences that can result from TMF failure [3]. Although TMF failures have historically been rare, both their frequency and severity are increasing due to aging infrastructure and climate-related stresses [4]. This trend underscores growing concerns regarding public health and environmental safety showcased in (Appendix A, Figure A1).

TMFs typically contain materials in a liquid or semi-liquid (mud) state, which inherently carry the potential to generate destructive mudflows in the event of structural failure. The consequences extend beyond environmental degradation, frequently resulting in severe socio-economic impacts for affected communities, including loss of livelihoods, displacement, and long-term economic disruption [5].

The increasing manifestations of climate change—particularly in the form of extreme hydrometeorological events such as intense precipitation and rapid snow melt—are becoming more frequently contributing factors, and in some cases the primary causes, of TMF failures. It is often burdened with great level of uncertainty, too, as can be seen on (Appendix A, Figure A2) [6]. These events are commonly classified as natural hazard-triggered technological disasters (NaTech), with TMF accidents serving as prominent examples of this phenomenon [7].

While the frequency of water-retention dam failures has declined over time, the rate of tailings management facility failures has remained consistent [8]. This persistent trend is attributed to several factors, including the use of tailings-derived materials for dyke construction, sequential dam raising methods, and fragmented regulatory frameworks [6]. The structural and functional differences between water-retention dams and TMFs necessitate distinct legal and policy approaches (Appendix A, Table A1). However, the complexity of TMF-related issues often leads to regulatory overlaps and, more critically, gaps—particularly during the transposition of international standards into national legislation. Failure to address TMF-specific challenges in policy frameworks can result in catastrophic outcomes, underscoring the need for targeted regulatory measures.

2. European Union Legal Framework of Tailing Management Facilities

The European Union employs various secondary legislative instrument regulations, directives, decisions, recommendations, and opinions which differ in legal force and application. During the transposition of EU policies into national legislation many gaps may arise and will be explored below.

EU legislative acts concerning TMFs are primarily represented by directives and decisions; however, these are not specifically tailored to TMFs and instead address broader contexts in which TMF-related issues are only collaterally included.

Effective TMF regulation requires addressing its potential impacts on water bodies, ecosystems, and downstream communities. Transposed EU legislation serves as a key instrument for preventing and mitigating these impacts at the national level. As a result, the relevant legislation will be examined across four thematic areas, each reflecting a distinct challenge related to TMFs and their impacts. Accordingly, the following sections will focus on four legislative domains relevant to TMFs—waste, water, disaster prevention, and general environmental protection.

2.1. Waste Legislation Concerning TMFs

Directive 2006/21/EC of the European Parliament and Council on the management of waste from extractive industries (commonly known as the Mining Waste Directive) [9] establishes a framework for sustainable mining practices, including tailings management. It emphasizes risk minimization, disaster prevention, sustainable environmental practices, public participation in emergency planning, financial guarantees, and the application of best available techniques.

This directive was partly informed by Directive 1999/31/EC on waste landfills, which notably excluded TMFs. In response to major TMF disasters at Aznalcóllar and Baia Mare (Appendix A, Figure A3 and Figure A4), it addressed hazardous waste management, cross-border contamination, risk communication, and public access to information, aligning with the Aarhus Convention [10]. Such disasters highlight the high-risk nature of TMFs and the urgent need for strong legislation and preventive measures due to their potential for long-term, cross-border environmental harm and damage done to the mining sector’s reputation.

Directive 2006/21/EC brought TMFs explicitly within its scope, introducing key provisions such as classification of high-risk facilities, mandatory accident prevention and emergency plans, public involvement, environmental monitoring, water protection, and consideration of transboundary environmental impacts. Additional waste-related legislation relevant to TMFs is summarized in (Appendix A, Table A2).

2.2. Water Legislation Concerning TMFs

To achieve and maintain good status of all EU surface and groundwater bodies Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy (Water Framework Directive—WFD) was adopted to prevent water contamination, conserve and or enhance its environmental status with relation to aquatic ecosystems [11].

Commission Directive 2014/101/EU [12], which amends the WFD (Water Framework Directive), aims to improve water monitoring practices, yet it still lacks a specific reference to TMFs. Additionally, Directive 2012/18/EC addresses groundwater protection against pollution and deterioration, including provisions relevant to potential TMF-derived contaminants such as AMD (acid mine drainage) [13].

2.3. Disaster Risk Reduction Concerning TMFs

Directive 2012/18/EU (called SEVESO III Directive) addresses the control of major-accident hazards involving dangerous substances and plays a key role in the prevention and management of TMF-related incidents [13]. Unlike its predecessor, Directive 96/82/EC, SEVESO III explicitly includes “operational tailings disposal facilities, including tailing ponds or dams, containing dangerous substances” under its scope.

However, SEVESO III applies only to TMFs containing substances classified as hazardous, excluding many facilities that still pose significant environmental or structural risks.

2.4. Environmental Issues Related Legislation Concerning TMFs

Directive 2004/35/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 April 2004 on environmental liability regarding the prevention and remedying of environmental damage [14] imposed the “polluter pays” principle, assigning bodies responsible for the remediation in case of failure. This directive defines the terms of “damage” and “imminent threat of damage”, which are transposed into national legislation.

Some general environmental directives (Regulation 2019/1010, Directive 2010/75/EU, Directive 2011/92/EU) may apply to TMFs in specific cases (e.g., EIA Directive 2011/92/EU, IPPC Directive 2010/75/EU and others), but none of them are directly tailored considering their unique properties.

3. Czech Policies and Legislation Concerning Tailing Management Facilities

3.1. Waste Legislation Concerning TMFs

In the Czech Republic, according to Act. No. 541/2020 Coll. [15] TMFs are considered specific waste disposal facilities in surface impoundments. Act No. 61/1988 Coll. [16] also specifies that TMFs are subject to the Mining Act too (Act No. 44/1988 [17]) if they fall under the activities mentioned in §2 (a)–(d). Additional legislation, such as Act. No.157/2009 Coll on Mining Waste manipulation, Act No. 61/1988 Coll. [18] defining the mining activities (where TMFs belong to) and Decree No. 51/1989 Coll. [19] on Health and safety during mineral processing, indirectly lays down the rules for monitoring, dam stability and emergency events which may take place.

3.2. Water Legislation Concerning TMFs

Tailing Management Facilities (TMFs) in the Czech Republic are classified as water works structures under Act No. 254/2001 Coll. [20] This legislation mandates that TMF operators prepare an emergency response plan to be enacted in the event of an incident. Decree No. 471/2001 Coll. [21] lays down the rules for technical safety oversight of TMFs and CTS 753310 [22] deals specifically with the design and operation of TMFs. Moreover, Czech Technical Standards (CTS) serve an important role in adhering to the policy interpreted and applied by laws.

Following the Bečva River disaster in 2020 [23], which involved a large-scale cyanide-induced fish kill, an emergency amendment—Act No. 182/2024 Coll. [24]—was introduced to enhance the provisions of Act No. 254/2001 Coll. This amendment aimed to improve inter-institutional cooperation, clarify responsibility attribution, and rectify deficiencies in accident reporting observed during the incident. Responsibility allocation among involved agencies remains unclear, particularly in trans-regional incidents, as demonstrated by the Bečva River case.

According to §41 of the amended act, any individual who causes or detects an accident is obligated to report it to the Fire Rescue Service. The Fire Rescue Service is then responsible for notifying the relevant water authority, the river basin administrator, the Czech Environmental Inspectorate, and the Police of the Czech Republic. The authority responsible for managing accident remediation is the competent water authority, while the Fire Rescue Service manages rescue operations and immediate response measures. In special cases requiring extraordinary expertise, the Czech Environmental Inspectorate may assume responsibility for both the cleanup and investigation.

3.3. Disaster Risk Reduction Concerning TMFs

While the European SEVESO III Directive includes TMFs under its scope, the Czech transposition Act No. 224/2015 Coll. on major accident prevention with the presence of dangerous substances [25] may exclude such sites due to its §1 (3) (e) clause. In cases where the TMF does not contain any dangerous substances and/or does not originate from mining activities, this law may not be applied. This phrasing might prove rather risky, especially considering the above-mentioned major TMF disasters.

In light of these regulatory gaps and the potential oversight of certain TMFs, particularly non-mining or legacy sites, attention has also turned to alternative risk mitigation strategies. In the broader context of TMF-related risk management, some studies have explored the potential reuse of industrial waste to reduce environmental hazards. For example, bottom ash or digestate from biogas production have demonstrated sorption capacities for selected heavy metals, suggesting their possible role in stabilization efforts or as remediation materials in specific scenarios [26,27]. Such valorization strategies may be particularly relevant where conventional remediation methods are lacking or economically unfeasible.

3.4. Environmental Issue-Related Legislation Concerning TMFs

As TMFs are classified as large-scale structures with the potential for significant environmental impacts, they fall under the purview of Act No. 100/2001 Coll. (Environmental Impact Assessment Act) [28]. This legislation mandates the assessment of environmental impacts in the event of new construction or substantial technological modifications of such facilities.

In the case of a dam breach or contamination of the surrounding environment, Act No. 167/2008 Coll. (on the Prevention and Remedying of Environmental Damage) may be applied [29]. The original version of this legislation contained a broad and insufficiently defined concept of ecological damage, and until 2021, it had not been applied. Following the Bečva River disaster, the act was amended to provide a more precise definition of ecological damage and to increase penalties for environmental violations; however, its practical application was not yet verified.

4. Identified Gaps

Unchecked policy inadequacies contribute to TMF failures with severe environmental consequences. While external triggers may initiate such events, legislative shortcomings often exacerbate their scale and impact. Gaps in regulation—outdated standards, weak enforcement, or poor inter-agency coordination—undermine TMF resilience and risk mitigation. Systematic legislative gap identification is therefore essential for detecting structural weaknesses, aligning policy with technological developments, and enhancing regulatory effectiveness. Proactive gap analysis is critical to preventing TMF-related disasters and protecting environmental and public health. Resulting from the comparison of the European and the Czech environmental and disaster prevention policies and their transpositions, several gaps were identified.

4.1. Fragmented and TMF-Unspecific Legislation

Due to their complex nature, TMFs fall under the jurisdiction of multiple legislative domains in the Czech Republic, most of which are not specifically tailored to TMFs. These include acts relating to waste management, mining, water protection, ecological damage, and disaster prevention.

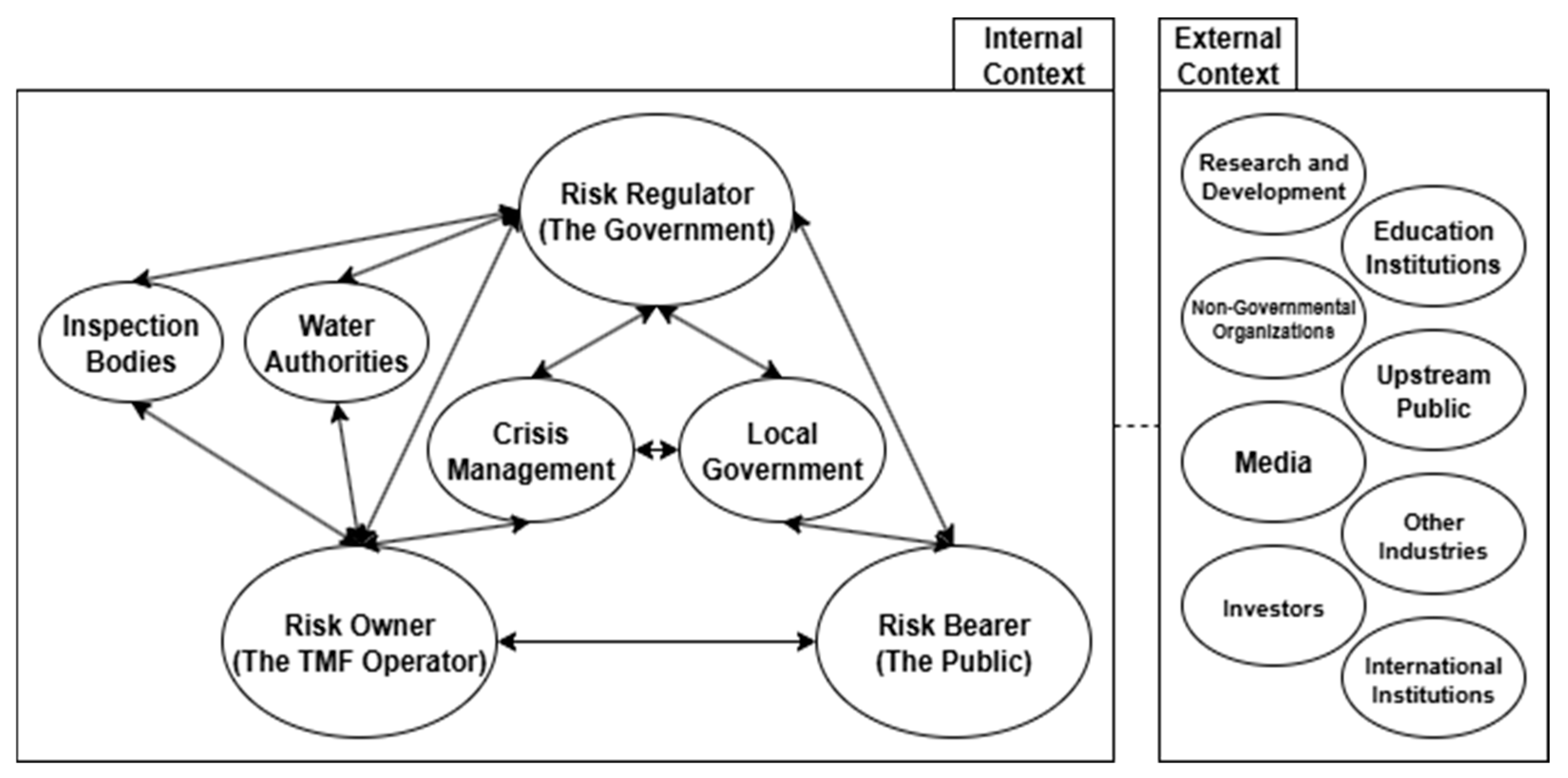

Operators and authorities often face overlapping or unclear responsibilities, hindering rapid decision-making during TMF emergencies. Many stakeholders may interfere with the process of TMF management (Figure 1), with each of them possessing various rights, responsibilities, interests, influence and risks.

Figure 1.

TMF stakeholder ecosystem concept model adapted from SAFETY4TMF project [30].

In the event of an emergency, this legal fragmentation can lead to confusion over which emergency response protocols should be applied, and under which legislative framework. Moreover, existing legislation generally does not adequately address historical ecological burdens—namely, closed, orphaned, or abandoned TMFs—that may pose latent risks and become environmental hazards in the future.

4.2. TMFs as Legacy Environmental Liabilities

While operational TMFs are documented in the national waterworks registry, historical or abandoned TMFs are listed separately in the SEKM (System of Evidence of Contaminated Sites) database [31]. Currently, SEKM identifies 71 such sites as TMFs, of which 17 are classified as being in environmentally uncertain conditions. In many of these cases, available data is either insufficient to confirm contamination or confirms contamination without being able to provide a more specific classification. As a result, these sites remain in a regulatory vacuum, with insufficient data and an unclear fate. Without proactive management, these facilities may evolve into serious environmental threats. Of the 17 facilities mentioned above classified as being in environmentally uncertain conditions, only 2 of them have some procedure of recultivation established to a lesser extent, whereas for the remaining sites, recultivation objectives have not been defined whatsoever.

4.3. Narrow Scope of Act No. 224/2015 Coll. on Major Accident Prevention

The Czech transposition of the EU SEVESO III Directive, Act No. 224/2015 Coll., may in certain circumstances exclude TMFs from its scope. Specifically, TMFs that do not contain legally defined “dangerous substances” and are not operated under mining legislation may not meet the inclusion criteria set out in the Act. However, TMFs can pose substantial risks unrelated to substance classification, such as failures due to structural instability, the release of mud or debris flows, or adverse impacts linked to biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and extreme pH levels. This is particularly relevant for non-mining TMFs (e.g., those related to fly ash or food industry residues, chemical industries), where the waste materials may exhibit hazardous properties despite lacking formal classification. Given that Act No. 224/2015 Coll. outlines obligations regarding public information, emergency preparedness, and post-accident reporting, the inclusion of TMFs under its scope should be more actively considered and formally defined.

4.4. Governance and Responsibility Gaps

The Bečva River disaster in 2020 highlighted significant deficiencies in the coordination and clarity of institutional responsibilities during environmental emergencies. Although Act No. 182/2024 Coll. amended existing law with the aim of improving reporting duties, it does not sufficiently clarify which authority is ultimately responsible for joint operations. Under the current legal framework, the water authority is tasked with managing accident remediation, while the Fire Brigade is responsible for immediate rescue and disposal efforts. The Act defines the accident site as either the location where the accident occurred or, if unknown, the location where it was first detected. This ambiguity becomes particularly problematic in incidents with trans-regional impacts, where the allocation of roles and activities remains undefined.

Unless legal and procedural responsibilities are clearly assigned, coordination failures like those seen in the Bečva incident are likely to repeat. As for the proposed steps further, defining a central coordinating authority for TMF-related accidents and pollution as well as updating and considering them in a joint register may turn out to be a good practice of the future.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of legislative transposition reveals that the current regulatory framework governing TMFs in the Czech Republic is tainted by fragmentation, non-specificity, and persistent governance ambiguities. These gaps hinder the effectiveness of environmental protection and disaster prevention principles, particularly in the context of legacy sites, ecological damage and disaster risk reduction.

First, the absence of TMF-specific provisions across multiple overlapping legal domains creates a risk of jurisdictional ambiguity, which may sabotage timely and coordinated emergency responses. Second, the inadequate integration of abandoned and orphaned TMFs into the national risk management framework exposes the environment to unresolved historical burdens in a temporarily dormant state. Third, the limited scope of Act No. 224/2015 Coll. may exclude TMFs based on narrow definitional criteria, thereby omitting facilities that may still pose significant hazards. Finally, recent legislative amendments aimed at clarifying emergency responsibilities for the case of river disasters remain insufficient, particularly for transboundary incidents where multi-agency coordination is essential.

To help prevent TMF-related disasters and accidental pollution, it would be highly beneficial to develop a conjunctive database of TMFs, accompanied by a methodology for risk assessment of sites with uncertain environmental conditions.

Addressing these challenges requires a unified TMF-specific legal framework, clear inter-agency coordination protocols, and consistent oversight of both active and legacy sites. Aligning national legislation more closely with comprehensive frameworks such as the SEVESO III Directive would enhance the resilience, transparency, public information availability and accountability of TMF governance and possible accidents happening in the future on the territory of the Czech Republic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B.; formal legislative analysis, P.B. and L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, P.B.; writing—review and editing, L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by VŠB–TUO, Faculty of Mining and Geology grant number SP2024/30, 2025/014.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Rising trend in TMF accidents over the decades [32].

Figure A1.

Rising trend in TMF accidents over the decades [32].

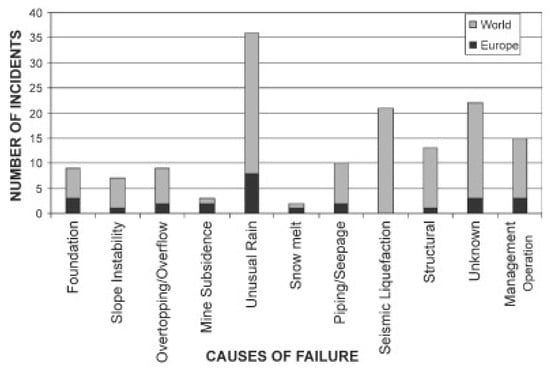

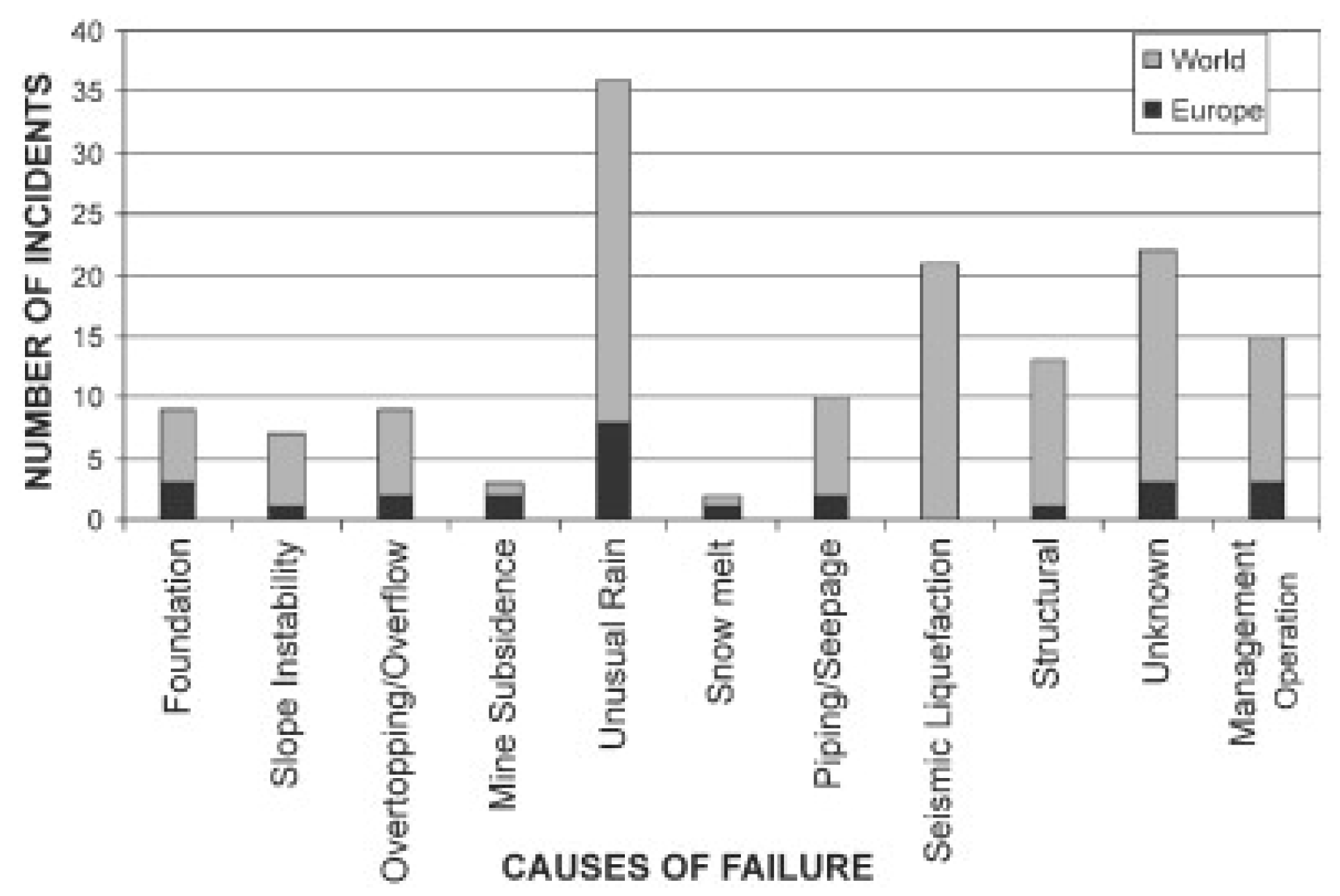

Figure A2.

Causes of TMF failures [33].

Figure A2.

Causes of TMF failures [33].

Table A1.

Key differences between TMFs and water-retention dams [8].

Table A1.

Key differences between TMFs and water-retention dams [8].

| Aspect | TMFs | Water-retention dam |

|---|---|---|

| Stored content | Tailings solids and technological water, diverse contaminant spectrum, concentrations | Water |

| Regulatory body | Mining bodies, Ministries of Environment | Ministries of the Public, Regional Authorities, National Dam Associations |

| Construction phase | Raised usually over mining operation time | Usually 1–3 years |

| Operation phase | 5–40 years (but uncertain) | Intended for 100 years (used for “as long as required by society”) |

| Closure and recultivation | Infinite closure period, potential for abandonment or orphanage | Often not addressed, can be decommissioned |

| Oversight | Owner and operator can change frequently | Usually, one engineering enterprise |

| Failure consequences | Mudflow damage, environmental contamination and derived socio-economic damage | Waterflow and inundation damage |

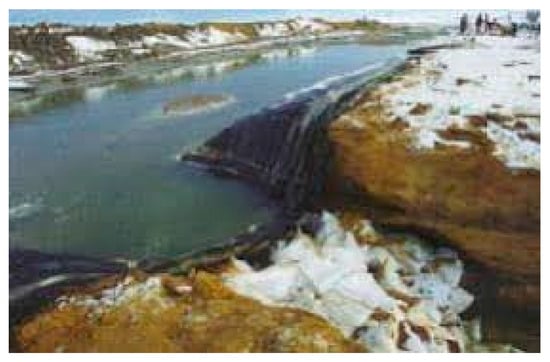

Figure A3.

The Aznacóllar TMF dam breach—The 1998 Aznalcóllar TMF failure contaminated over 4500 hectares with sludge and acidic water, affecting agriculture, water bodies, and the Doñana National Park [34,35].

Figure A3.

The Aznacóllar TMF dam breach—The 1998 Aznalcóllar TMF failure contaminated over 4500 hectares with sludge and acidic water, affecting agriculture, water bodies, and the Doñana National Park [34,35].

Figure A4.

The Baia Mare TMF dam breach—In 2000, another incident, the Baia Mare cyanide spill, reached the Danube Delta, with toxicity detected up to 2000 km downstream and near-total aquatic life loss within the first 30–40 km [34,35].

Figure A4.

The Baia Mare TMF dam breach—In 2000, another incident, the Baia Mare cyanide spill, reached the Danube Delta, with toxicity detected up to 2000 km downstream and near-total aquatic life loss within the first 30–40 km [34,35].

Table A2.

Other TMF waste-related legislative acts [36,37,38,39].

Table A2.

Other TMF waste-related legislative acts [36,37,38,39].

| Legislation Act | Scope | TMF-Related Aspects |

|---|---|---|

| Decision 2009/335/EC | Technical guidelines for the establishment of the financial guarantee | Suggests TMF-related aspects to be considered for the calculation |

| Decision 2009/337/EC | Definition of the criteria for the classification of waste facilities | Classification of waste facilities, introduction of Category A |

| Decision 2009/359/EC | Completing the definition of inert waste | Defines conditions for inert waste |

| Decision 2009/360/EC | Completing the technical requirements for waste characterization | Provides guidance for waste characterization |

References

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Safety Guidelines and Good Practices for Tailings Management Facilities. New York and Geneva. 2014. Available online: https://unece.org/environment-policy/publications/safety-guidelines-and-good-practices-tailings-management-facilities (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D.; Lèbre, É.; Svobodova, L.; Peréz Murillo, G. Catastrophic Tailings Dam Failures and Disaster Risk Disclosure. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 42, 101361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luino, F.; De Graff, J.V. The Stava Mudflow of 19 July 1985 (Northern Italy): A Disaster that Effective Regulation Might Have Prevented. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 1029–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrill, J.; Chambers, D.; Emerman, S.; Harkinson, R.; Kneen, J.; Lapointe, U.; Maest, A.; Milanez, B.; Personius, P.; Sampat, P.; et al. Safety First Guidelines for Responsible Mine Tailings Management. Earthworks, MiningWatch Canada and London Mining Network. 2022. Available online: https://earthworks.org/resources/safety-first/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Oliveira, L.A.; Braga, M.A.; Prosdocimi, G.; de Souza Cunha, A.; Santana, L.; da Gama, F. Improving Tailings Dam Risk Management by 3D Characterization from Resistivity Tomography Technique: Case Study in São Paulo—Brazil. J. Appl. Geophys. 2023, 210, 104924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, S.; Li, Q. Tailing Dam Failures: A Review of Last One Hundred Years. Geotech. News 2010, 28, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kamke, C. Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change and Natech Risks for Tailings Management Facilities (TMFs) in Central Asia. In Proceedings of the Second Meeting of the Inter-Institutional Working Group on Water Pollution and Tailings Safety in Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 9 April 2025; Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2025-06/Session%202_2_Impact%20of%20CC%20and%20Natech%20risks%20for%20TMFs_ENG.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Roche, C.; Thygesen, K.; Baker, E. Mine Tailings Storage: Safety Is No Accident—A Rapid Response Assessment; United Nations Environment Programme and GRID-Arendal: Arendal, Norway, 2017; ISBN 978-82-7701-170-7. [Google Scholar]

- Council Directive 2006/21/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006 on the Management of Waste from Extractive Industries and Amending Directive 2004/35/EC. Official Journal of the European Union. 2006, L 102/15. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2006/21/oj/eng (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Council Directive 1999/31/EC of 26 April 1999 on the Landfill of Waste. Official Journal of the European Union. 1999, L 182/1. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/1999/31/oj/eng (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy. Official Journal of the European Union. 2000, L 327/1. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/60/oj (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Commission Directive 2014/101/EU of 30 October 2014 Amending Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy. Official Journal of the European Union. 2014, L 311/32. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/101/oj/eng (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Directive 2012/18/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012 on the Control of Major-Accident Hazards Involving Dangerous Substances, Amending and Subsequently Repealing Council Directive 96/82/EC. Official Journal of the European Union. 2012, L 197/1. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2012/18/oj/eng (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Directive 2004/35/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 April 2004 on Environmental Liability with Regard to the Prevention and Remedying of Environmental Damage. Official Journal of the European Union. 2004, L 143/56. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2004/35/oj/eng (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Zákon č. 541/2020 Sb. Zákon o Odpadech. 2020. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2020-541 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Zákon č. 61/1988 Sb. Zákon České národní rady o hornické činnosti, výbušninách a o státní báňské správě. 1988. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/1988-61 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Zákon č. 44/1988 Sb. Zákon o ochraně a využití nerostného bohatství (horní zákon). 1988. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/1988-44 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Zákon č. 157/2009 Sb. Zákon o nakládání s těžebním odpadem a o změně některých zákonů. 2009. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2009-157 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Vyhláška č. 51/1989 Sb. Vyhláška Českého báňského úřadu o bezpečnosti a ochraně zdraví při práci a bezpečnosti provozu při úpravě a zušlechťování nerostů. 1989. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/1989-51 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Zákon č. 254/2001 Sb. Zákon o vodách a o změně některých zákonů (vodní zákon). 2001. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2001-254 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Vyhláška č. 471/2001 Sb. Vyhláška Ministerstva zemědělství o technickobezpečnostním dohledu nad vodními díly. 2001. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2001-471 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- ČSN 75 3310 (753310). Odkaliště. 2009. Available online: https://www.technicke-normy-csn.cz/csn-75-3310-753310-225502.html# (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Vyšetřovací komise k ekologické katastrofě na řece Bečvě. Závěrečná zpráva. Sněmovní dokument 9016. 2021. Available online: https://www.psp.cz/sqw/text/orig2.sqw?idd=198287 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Zákon č. 182/2024 Sb. Zákon, kterým se mění zákon č. 254/2001 Sb., o vodách a o změně některých zákonů (vodní zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů, zákon č. 114/1992 Sb., o ochraně přírody a krajiny, ve znění pozdějších předpisů, a zákon č. 465/2023 Sb., kterým se mění zákon č. 416/2009 Sb., o urychlení výstavby dopravní, vodní a energetické infrastruktury a infrastruktury elektronických komunikací (liniový zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů, a další související zákony. 2024. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2024-182 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Zákon č. 224/2015 Sb. Zákon o prevenci závažných havárií způsobených vybranými nebezpečnými chemickými látkami nebo chemickými směsmi a o změně zákona č. 634/2004 Sb., o správních poplatcích, ve znění pozdějších předpisů. 2015. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2015-224 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Kodymová, J.; Heviánková, S.; Kyncl, M.; Rusín, J. Testing the Impact of the Waste Product from Biogas Plants on Plant Germination and Initial Root Growth. Inż. Miner. 2021, 1, 25–31. Available online: https://dspace.vsb.cz/items/159f8943-03f0-4e46-8b35-1bb1fce768b8 (accessed on 21 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pertile, E.; Dvorský, T.; Václavík, V.; Šimáčková, B.; Balcařík, L. Utilization of Bottom Ash from Biomass Combustion in a Thermal Power Plant to Remove Cadmium from the Aqueous Matrix. Molecules 2024, 29, 5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zákon č. 100/2001 Sb. Zákon o posuzování vlivů na životní prostředí a o změně některých souvisejících zákonů. 2001. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2001-100 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Zákon č. 167/2008 Sb. Zákon o předcházení ekologické újmě a o její nápravě a o změně některých zákonů. 2008. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2008-167 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Interreg-Danube Region—SAFETY4TMF Project Website. Internal Project Documents. Available online: https://interreg-danube.eu/projects/safety4tmf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Systém Evidence Kontaminovaných Míst 3 (1.2.15). Available online: https://www.sekm.cz/portal/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Lin, S.-Q.; Wang, G.-J.; Liu, W.-L.; Zhao, B.; Shen, Y.-M.; Wang, M.-L.; Li, X.-S. Regional Distribution and Causes of Global Mine Tailings Dam Failures. Metals 2022, 12, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, M.; Benito, G.; Salgueiro, A.R.; Díez-Herrero, A.; Pereira, H.G. Reported Tailings Dam Failures: A Review of the European Incidents in the Worldwide Context. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 152, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreft-Burman, K.; Saarela, J.; Anderson, R. Sustainable Improvement in Safety of Tailings Facilities TAILSAFE—A European Research and Technological Development Project Contract Number: EVG1-CT-2002-00066. Tailings Management Facilities Legislation, Authorisation, Management, Monitoring and Inspection Practices. 2005. Available online: https://www.tailsafe.com/pdf-documents/TAILSAFE_Thickened_Tailings.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Communication from the Commission. Safe Operation of Mining Activities: A Follow-Up to Recent Mining Accidents. COM/2000/0664 Final. 2000. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52000DC0664 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Commission Decision of 20 April 2009. On Technical Guidelines for the Establishment of the Financial Guarantee in Accordance with Directive 2006/21/EC Concerning the Management of Waste from Extractive Industries. Official Journal of the European Union. 2009, L 101/25. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dec/2009/335/oj/eng (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Commission Decision of 20 April 2009. On the Definition of the Criteria for the Classification of Waste Facilities in Accordance with Annex III of Directive 2006/21/EC Concerning the Management of Waste from Extractive Industries. Official Journal of the European Union. 2009, L 102/7. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dec/2009/337/oj/eng (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Commission Decision of 30 April 2009. Completing the Definition of Inert Waste in Implementation of Article 22(1)(f) of Directive 2006/21/EC Concerning the Management of Waste from Extractive Industries. Official Journal of the European Union. 2009, L 110/46. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dec/2009/359/oj/eng (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Commission Decision of 30 April 2009. Completing the Technical Requirements for Waste Characterisation Laid Down by Directive 2006/21/EC on the Management of Waste from Extractive Industries. Official Journal of the European Union. 2009, L 110/48. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dec/2009/360/oj/eng (accessed on 16 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).