Abstract

Autonomous vehicle control has undergone remarkable developments in recent years, especially in maneuvering at the limits of traction. These developments promise improved maneuverability and safety, but they also highlight a constant challenge: translating control strategies developed in simulation into robust, real-world applications. The complexity of real-world environments, with their inherent uncertainties and rapid changes, poses significant obstacles for autonomous systems that need to dynamically adapt to unpredictable conditions, such as varying traction. The aim of this research is to investigate the effectiveness of robust adversarial reinforcement learning (RARL) for controlling circular drift maneuvers under dynamic road adhesion changes and uncertainties. The presented simulation results show that agents trained with RARL can enhance agents developed using only standard reinforcement learning techniques, where they were most critically vulnerable, such as sudden significant loss of traction during the drift initiation phase. This could present another step towards the application of more robust autonomous systems.

1. Introduction

Autonomous vehicle (AV) control at the limits of handling has emerged as a crucial frontier for improving safety, stability, and maneuverability in extreme driving scenarios. Recent years have witnessed growing interest in enabling AVs to perform complex dynamic maneuvers (such as drifting) that inherently operate in the nonlinear region of tire dynamics and demand precise, adaptive control. Traditional autonomous driving solutions, often designed for structured environments, can falter under conditions where the dynamics of the environment—like road adhesion—can suddenly change, prompting a shift toward robust, learning-based strategies and advanced control-theoretic frameworks.

A multitude of control strategies have been proposed to tackle these challenges. Classical control methods, such as model predictive control (MPC) [1,2,3] and linear quadratic regulator (LQR) [4], have been successfully applied to path tracking and drift stabilization by leveraging simplified vehicle models and optimization schemes, even under model-based and environmental uncertainties, such as varying road friction. These approaches offer transparency and safety guarantees, and some have demonstrated feasibility in 1:5 scaled or full-scale vehicle experiments [5,6].

Parallel to these developments, data-driven and neural network-based approaches have gained traction for their ability to approximate unmodeled dynamics [7] and learn control policies directly from experience [8]. Notably, hybrid schemes combining traditional control structures with neural components have been developed to track drift references and adapt to varying terrain using online learning and virtual sensing [9]. Several works have reported real-world implementation of such strategies on test vehicles, including production sports cars retrofitted for by-wire control [10].

Reinforcement Learning (RL) could also be a powerful tool for controlling dynamic maneuvers at the limits of handling [11,12,13,14]. However, it can be a significant challenge to train such agents that could perform well in the real world [15,16] due to the challenge of crossing the so-called sim-to-real gap. On the other hand, RL could still have a reasonable advantage for solving this problem since its wide range of applicability and potential for handling uncertainties for autonomous vehicles [17,18] and other fields too [19].

Apart from the above, another promising approach to bridging this sim-to-real gap is Robust Adversarial Reinforcement Learning (RARL) [20]. RARL enhances the resilience of learned policies by introducing adversarial agents during training. These agents are not simple noise injectors but are instead trained to actively perturb the learning process, creating challenging scenarios such as sudden changes in road adhesion or dynamic friction profiles. By confronting the control agent with these tailored disturbances during training, RARL encourages the development of policies that generalize better to unpredictable real-world conditions. The main advantage of RARL against other conventional approaches, like MPC or game theoretic approaches, is that it does not require explicit definitions for the disturbances that must be accounted for in the training environment; rather, this method focuses on finding these disturbances through learning [15].

This paper aims to explore the application of RARL to the specific problem of circular drift maneuvering under dynamic traction conditions. Drifting, particularly at high slip angles, presents a unique set of control challenges due to the nonlinear and rapidly changing dynamics of tire-road interaction. As such, it serves as a compelling test case for evaluating the robustness of control strategies.

2. Methodology

2.1. Vehicle Modeling and Simulation Environment

In this paper, for training both the drift control and adversary agents, a two-wheel planar RWD vehicle model [21] was implemented in a MATLAB/Simulink (R2025a) simulation environment. The model’s continuous state space has three dimensions (): the longitudinal velocity , the lateral velocity , and the yaw rate . The state transition function can be written with the following equations:

where is the lateral acceleration, is the longitudinal acceleration, is the yaw acceleration, is the vehicle’s mass, is the yaw inertia of the vehicle’s body frame, is the longitudinal force component, is the lateral force component, and is the yaw moment of the vehicle. The vehicle’s side-slip angle is very important from the aspect of drifting, and it is defined for this model as follows:

The model’s actuators are the current accelerator pedal position and the steering wheel angle , thus, . The model also considers actuator dynamics, which means that the actuator demands are transferred through an actuator model to calculate a realized accelerator pedal input and steering wheel angle .

The vehicle model is augmented with a combined-slip Magic Formula tire model [22,23] to address the nonlinearities during drifting. The equations of the tire model connect the actuators and the vehicle force components and moments together. Further details and specifications of this vehicle model can be addressed in [15].

2.2. Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning (RL) is a machine learning framework in which agents learn to perform tasks through repeated interactions with a dynamic environment, guided by the objective of maximizing cumulative rewards. In the context of this study, the environment comprises the vehicle and its surrounding conditions. The primary RL agent, referred to as the protagonist, is responsible for controlling the vehicle’s actuators by selecting actions based on the observed state of the environment. Its goal is to learn a control policy that maximizes a reward signal associated with successful execution of a circular drifting maneuver.

In this paper, the protagonist’s state space consists of the vehicle’s state vector , along with the derivate state vector :

The protagonist’s task is to drive the vehicle, with an inference time of . The action space of the protagonist is identical to the actuator space of the vehicle model:

The reward function is designed for the protagonist to perform a quasi-equilibrium circular drifting maneuver with a target speed of , a target side-slip angle of , and target path curvature . From and , a yaw rate target was derived as follows:

The designed reward function has three components:

The first component is responsible for encouraging the agent to initiate and stabilize the target drift maneuver based on and as follows:

The second component augments the agent’s goal to try to find a yaw equilibrium around the target state to ensure system stability:

The third component encourages the agent to minimize the excessiveness of the actuator commands:

The main idea in this paper is to introduce an adversary agent using adversarial RL [20] to enhance robustness under dynamically changing road adhesion conditions. The adversary achieves this by dynamically modifying the road friction coefficient based on the current state of the environment. Thus, always the same information is known for both the protagonist and the adversary, which is the vehicle’s velocities and accelerations. The adversary’s exact action space was defined as the following:

Thus, the adversary is able to select any value of road friction between 0.35 and 1.05. These represent values between snow-covered roads and commonly traversed dry asphalt. Since the first protagonist was able to ignore oscillating sudden traction changes which were more frequent than 10 Hz, the inference time of the adversary was set to to increase the ability to find more practical disturbances. The adversary’s goal is to minimize the protagonist’s reward function, thus, .

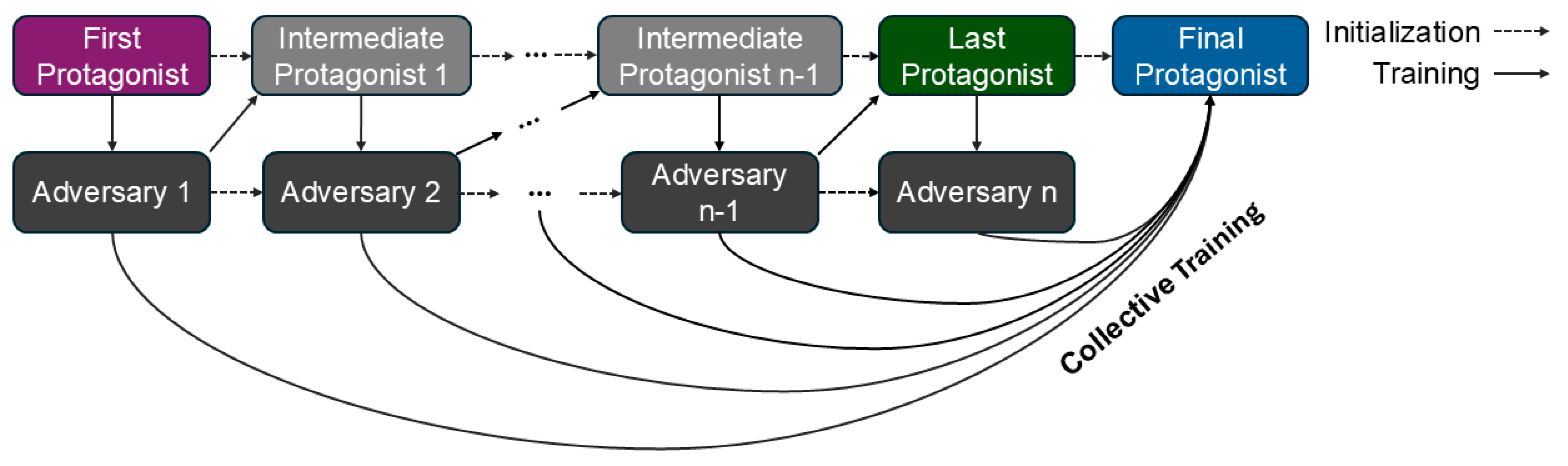

The protagonists and adversaries were trained in an iterative asynchronous manner (see Figure 1). A first protagonist was trained in advance in environments where the road friction coefficient was constant during training episodes, although diverse between them, selected in the beginning of every episode from the interval . Then, the first adversary was trained against the first protagonist. After the first adversary reached a certain average episode reward value, a second (intermediate) protagonist was initialized based on the first protagonist, and trained against the first adversary. This process was repeated until 10 adversaries were trained. Then, initialized from the last intermediate protagonist, a final protagonist was trained on all of the adversaries collectively to reduce overfitting and forgeting due to the iterative manner of the method.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the Collective Adversarial Reinforcement Learning training scheme with adversaries.

The number of adversaries was determined with early stopping. After each iteration, we evaluated the previous protagonist’s performance on this new adversary. If the episode reward of the protagonist did not decrease compared to the previous iteration, the iterative training process was stopped, and the final collective training step followed.

Each training episode started from the same initial state , which is a constant speed forward movement. Every training episode lasted for . The main point behind this difference between the start speed and is to also demand from the agent to accelerate the vehicle to a desired speed for drifting, not just to perform a drift maneuver at the current speed.

3. Results

3.1. Collective Training Resulted in More Robust Autonomous Drifting

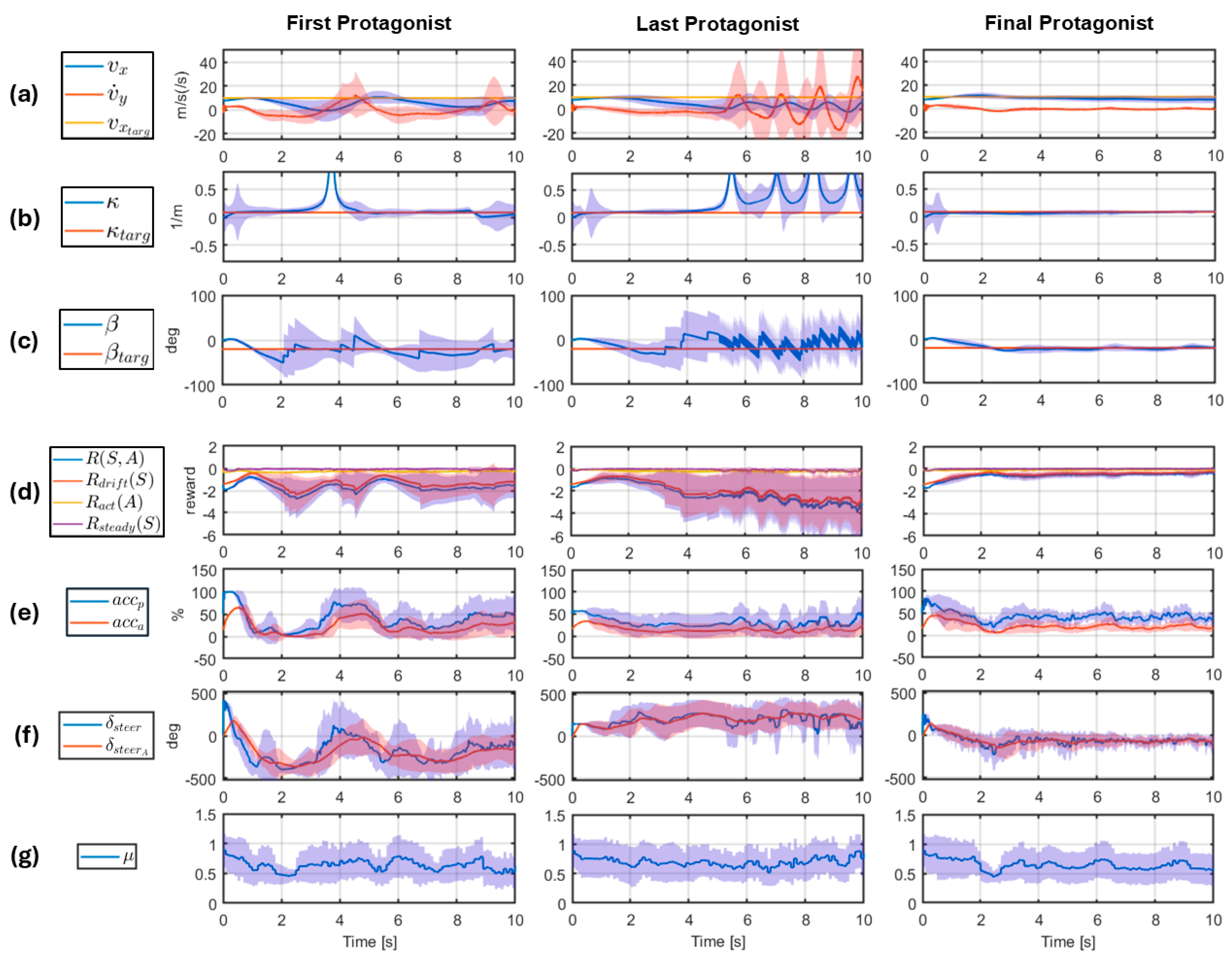

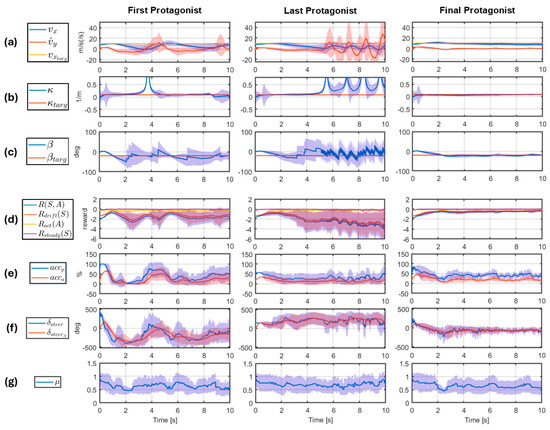

In Figure 2, the evaluation of first, last, and final protagonists on a 10 s long episode simulation is shown.

Figure 2.

Performance comparison for autonomous drifting between the first (1st column), final (2nd column), and last (3rd column) protagonists under the effects of the 10 adversaries with confidence intervals.

Figure 2 shows the longitudinal state variables , , and the target (row (a)), the path curvature and the target (row (b)), the side slip angle and the target (row (c)), the agent’s current reward , along with the reward components , , and (row (d)), the actuator commands and their realized values (rows (e,f)), and the current adhesion coefficient (row (g)). The bold lines show the mean values at the given timestamp across evaluations on the 10 trained adversary policies (one evaluation per adversary). The shaded areas around the bold lines serve as showing the uncertainty of the controller with respect to the disturbances at these timesteps by picturing the standard deviation of the signals.

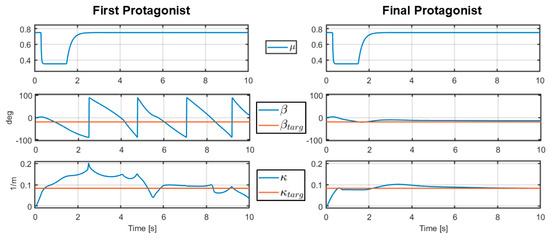

3.2. Realizing Stable Autonomous Drifting in Case of Sudden Loss in Traction

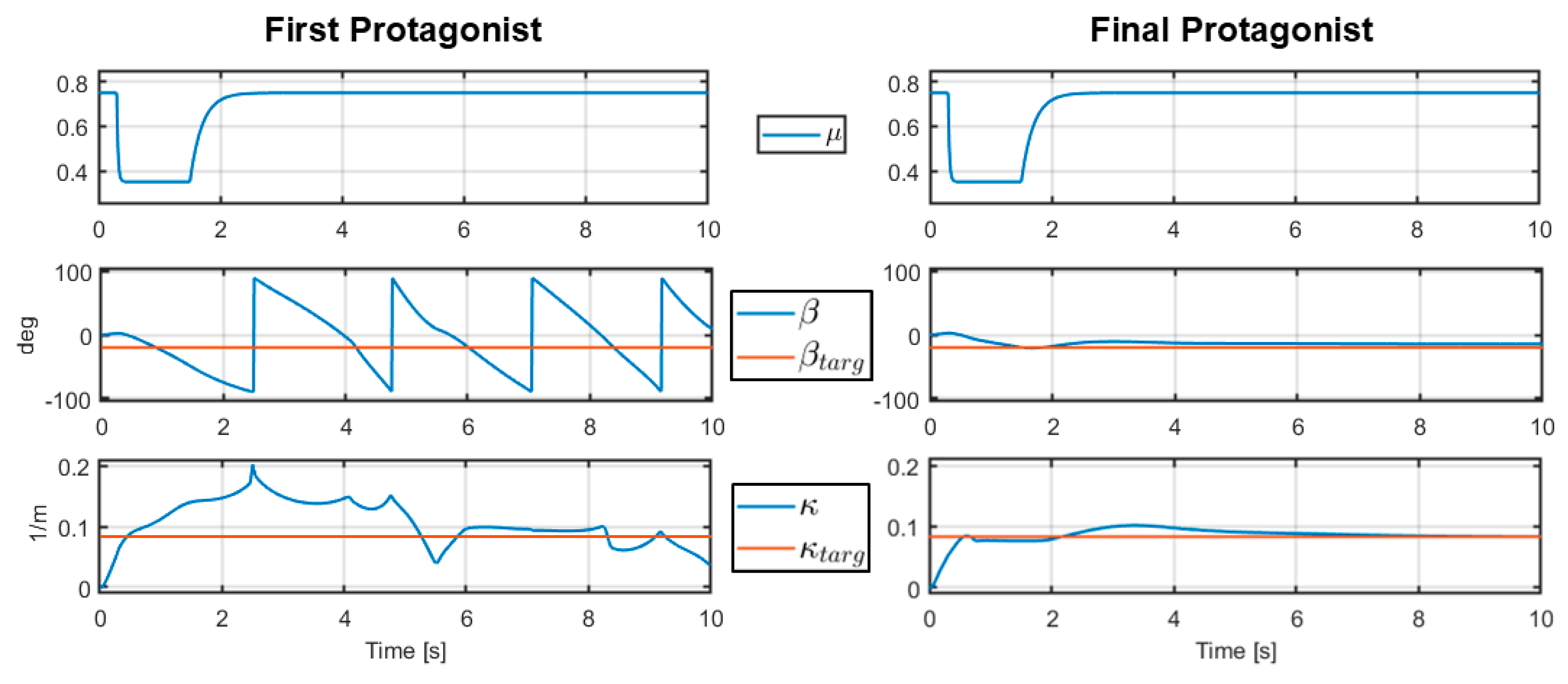

Figure 3 shows a scope graph of a 10 s long simulation in a case where the adhesion coefficient drops during the drift initiation phase from to , stays there for a while, then increases back to . This case is a representation of a real-world event where the car would traverse onto a heavily wet or snow-covered area of the road during a drift initiation phase, then proceed to a dry asphalt surface again. In the figure, the first row shows the changes in the adhesion coefficient , the second row shows the side slip angle and the target , and the third row shows the path curvature and the target . While they are not shown in the figure, the longitudinal state variables , , and the actuator commands and in the first protagonist’s case are similar to the ones shown in the left column in Figure 2. This is also true for the final protagonist, but with the right column in Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Comparison between the first (left column) and final (right column) protagonists in case of a sudden loss of traction under the drift initiation phase.

4. Discussion

Figure 2 tells a lot about the importance of the collective training step of the algorithm. As it might be obvious, the first protagonist performs poorly under the influence of the adversaries. The method itself proves its point here that the adversaries aim at the protagonist’s weakness during training. What is more important is that the last protagonist performs even worse in confidence under the different adversaries. This means that the last protagonist is overfitting on the last adversary’s manipulations. This shows the critical importance of the collective training step, since the final protagonist can confidently handle all adversaries with high performance. The last row in Figure 2 also shows that the trained adversaries were indeed utilizing the whole range of adhesion coefficient values during training to find the weak spots of the agent.

Nevertheless, these findings might also highlight an issue that the trained adversaries could correlate with each other. For example, since the 5th intermediate protagonist possibly overfitted on the 4th adversary and might have some knowledge left on the 2nd and 3rd adversaries, the 1st adversary might be barely remembered. Thus, the 5th adversary could be close to or identical to the 1st adversary and still be a problem for the 5th intermediate protagonist. This phenomenon could be addressed, for example, with an extended collective training structure, where each intermediate protagonist is trained on all the previous adversaries. Another solution might be to apply a more careful early stopping method.

The use case presented in Section 3.2 is a case which was found by the first adversary during training. After the first iteration, the first protagonist was evaluated under the influence of the first adversary. It was found that the first protagonist was unable to initiate a successful drift in the case where the road adhesion suddenly dropped under the drift initiation phase. As Figure 3 shows, the side slip angle in the first protagonist’s case is way off the target, and the values can be translated as the vehicle’s spinning out after the road adhesion had dropped. On the other hand, the final protagonist manages to initiate and even stabilize the drift with high performance even in this case. This also means that the training method indeed produces a robust control agent against the cases which the adversaries have presented, even if it occurred during the first iteration. It is also very important that this specific use case could occur in real life with a decent probability, so the fact that the first protagonist failed during this case is critical.

5. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated the effectiveness of Robust Adversarial Reinforcement Learning (RARL) in enhancing the resilience and performance of autonomous drifting controllers under dynamically changing road adhesion conditions. The results confirm that standard reinforcement learning approaches are insufficient for handling rapid and unexpected changes in environmental dynamics, particularly during critical phases such as drift initiation. In contrast, agents trained with adversarial reinforcement learning consistently outperformed their non-robust counterparts, showing improved stability, tracking accuracy, and robustness against unseen scenarios. The final protagonist, trained through a collective adversarial strategy, exhibited strong generalization across all adversarial challenges, validating the benefit of ensemble adversary training to mitigate overfitting. However, the iterative training framework may result in adversary redundancy or policy forgetting, which future research should address through mechanisms like continual learning, diversity-preserving adversarial generation, or curriculum-based training. Future work will aim to improve the applied methodology to address the potential issues discovered, while also testing the final protagonist on real vehicles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.T. and Z.J.V.; methodology, S.H.T. and Z.J.V.; software, S.H.T.; validation, S.H.T. and Z.J.V.; formal analysis, S.H.T. and Z.J.V.; investigation, S.H.T. and Z.J.V.; resources, Z.J.V.; data curation, S.H.T. and Z.J.V.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.T.; writing—review and editing, S.H.T. and Z.J.V.; visualization, S.H.T.; supervision, Z.J.V.; project administration, Z.J.V.; funding acquisition, S.H.T. and Z.J.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research described in this publication, which was carried out by the HUN-REN Institute of Computer Science and Control, and the Budapest University of Technology and Economics, was partially supported by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology and the National Research, Development, and Innovation Office within the framework of the National Laboratory of Autonomous Systems (RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00002). The project is supported by the Doctoral Excellence Fellowship Programme (DCEP), which is funded by the National Research Development and Innovation Fund of the Ministry of Culture and Innovation and the Budapest University of Technology and Economics, under a grant agreement with the National Research, Development, and Innovation Office (2020-2.1.1-ED-2023-00239). The research of the adversarial agents was supported by Project no. 2024-2.1.1-EKOP-2024-00003 that has been implemented with the support provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the EKOP-24-3-BME-295 funding scheme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Czibere, S.; Domina, Á.; Bárdos, Á.; Szalay, Z. Model Predictive Controller Design for Vehicle Motion Control at Handling Limits in Multiple Equilibria on Varying Road Surfaces. Energy 2021, 14, 6667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas, J.; Wurts, J.; Stein, J.L.; Ersal, T. Contingent Nonlinear Model Predictive Control for Collision Imminent Steering in Uncertain Environments. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 14330–14335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Jiang, C.; Qiu, M.; Wu, D.; Zhang, B. Research on Intelligent Vehicle Lane Changing and Obstacle Avoidance Control Based on Road Adhesion Coefficient. J. Vib. Control. 2022, 28, 3269–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárdos, Á.; Domina, Á.; Tihanyi, V.; Szalay, Z.; Palkovics, L. Implementation and Experimental Evaluation of a MIMO Drifting Controller on a Test Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 19 October–13 November 2020; pp. 1472–1478. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Yang, S.; Yang, Y.; Song, W.; Fu, M. A Multi-Layer Drifting Controller for All-Wheel Drive Vehicles Beyond Driving Limits. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2024, 29, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, S.; Bertipaglia, A.; Shyrokau, B. A Nonlinear Model Predictive Control for Automated Drifting with a Standard Passenger Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM), Besançon, France, 15–19 July 2024; pp. 284–289. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X.; He, X.; Lv, C.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J. Adaptive-Neural-Network-Based Robust Lateral Motion Control for Autonomous Vehicle at Driving Limits. Control Eng. Pract. 2018, 76, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, M.; Kanarachos, S. Teaching a Vehicle to Autonomously Drift: A Data-Based Approach Using Neural Networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2018, 153, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Xu, K.; Cui, Y.; Zou, Y.; Pan, Z. Learning-Based Motion Control of Autonomous Vehicles Considering Varying Adhesion Road Surfaces. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Macau, China, 8–12 October 2022; pp. 4259–4264. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, N.; Thompson, M.; Dallas, J.; Goh, J.Y.M.; Subosits, J. Drifting with Unknown Tires: Learning Vehicle Models Online with Neural Networks and Model Predictive Control. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 2–5 June 2024; pp. 2545–2552. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, P.; Mei, X.; Tai, L.; Sun, Y.; Liu, M. High-Speed Autonomous Drifting with Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domberg, F.; Wembers, C.C.; Patel, H.; Schildbach, G. Deep Drifting: Autonomous Drifting of Arbitrary Trajectories Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 7753–7759. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, S.H.; Viharos, Z.J.; Bárdos, Á. Autonomous Vehicle Drift with a Soft Actor-Critic Reinforcement Learning Agent. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 20th Jubilee World Symposium on Applied Machine Intelligence and Informatics (SAMI), Herl’any, Slovakia, 2–5 March 2022; pp. 000015–000020. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, S.H.; Bárdos, Á.; Viharos, Z.J. Tabular Q-Learning Based Reinforcement Learning Agent for Autonomous Vehicle Drift Initiation and Stabilization. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2023, 56, 4896–4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, S.H.; Viharos, Z.J.; Bárdos, Á.; Szalay, Z. Sim-to-Real Application of Reinforcement Learning Agents for Autonomous, Real Vehicle Drifting. Vehicle 2024, 6, 781–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djeumou, F.; Thompson, M.; Suminaka, M.; Subosits, J. Reference-Free Formula Drift with Reinforcement Learning: From Driving Data to Tire Energy-Inspired, Real-World Policies. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.20990. [Google Scholar]

- Fayyazi, M.; Golafrouz, M.; Jamali, A.; Lappas, P.; Jalili, M.; Jazar, R.; Khayyam, H. Adaptive Multi-Armed Bandit Reinforcement Learning-Based Energy Management and Real-Time Control System for Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 7303–7312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laflamme, C.; Doppler, J.; Palvolgyi, B.; Dominka, S.; Viharos, Z.J.; Haeussler, S. Explainable Reinforcement Learning for Powertrain Control Engineering. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 146, 110135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viharos, Z.J.; Jakab, R. Reinforcement Learning for Statistical Process Control in Manufacturing. Measurement 2021, 182, 109616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.; Davidson, J.; Sukthankar, R.; Gupta, A. Robust Adversarial Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 2817–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Jazar, R.N. Advanced Vehicle Dynamics, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, E.; Nyborg, L.; Pacejka, H.B. Tyre Modelling for Use in Vehicle Dynamics Studies. SAE Trans. 1987, 96, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacejka, H.B. Tire and Vehicle Dynamics, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).