Abstract

Deploying autonomous vehicles in urban mobility systems promises significant improvements in safety, efficiency, and sustainability. On the other hand, running these vehicles in the continuously changing and often uncertain conditions of modern cities turns out to be a major challenge. These cars need advanced systems that can continuously change in order to observe conditions. This paper puts forward a new way that brings together multiple LIDAR sensors for the real-time spotting and following of objects, along with adaptive motion planning methods made to handle the difficulties of city traffic. Using LIDAR-based mapping for environmental modeling and predictive tracking techniques helps the system build a richly detailed, consistently updating depiction of surroundings that supports accurate and quick decisions. Another feature of the system is dynamic path planning that ensures safe navigation by considering traffic, pedestrian movement, and road conditions. Simulations carried out in highly dense urban scenarios show improvement in collision avoidance, path-planning optimization, and response to environmental dynamics. Such outcomes prove that combining multi-LIDAR tracking and adaptive motion planning contributes significantly to the performance and safety of an autonomous vehicle when operating in very complex urban conditions.

1. Introduction

The broad use of self-driving cars can greatly change city transport systems, improve traffic flow, and cut down on accidents. There are, however, many major obstacles in the introduction of autonomous vehicles to high-density, constantly shifting urban dynamics. A very strong perception system that is able to see and follow all of the moving parts is needed, along with equally advanced decision-making mechanisms that can adjust to unexpected changes, to ensure safe and good self-driving car performance in such places. This has placed LIDAR technology among the crucial technologies for navigation within autonomy, as it can offer accurate spatial information [1]. Using many LIDAR sensors, autonomous vehicles can make fine 3D maps of their surroundings, which helps them see things at different distances and angles with great accuracy [2]. Even with these perks, merging data from several LIDAR sensors and dealing with the issues of real-time dynamic tracking and path planning in cities is still difficult [3].

Safety calls for the fusion of LIDAR data from all sensors to track and predict dynamic, moving elements such as pedestrians, cyclists, and other vehicles in the environment. Sudden appearances and disappearances of elements, as well as unpredictable behavior, pose great challenges to traditional algorithms in keeping their accuracy [4]. High-resolution data needs to be processed performatively in real-time for effective decision-making within an appropriate time frame; this also further adds to the complexity [5]. In addition, autonomous vehicles need to dynamically adapt to altering environments that include construction, traffic signs, and other unpredictable road users [6]. Real-time planning that considers safety, comfort, and efficiency allows an autonomous vehicle to run through such scenarios [7]. This paper presents a new framework for the fusion of multi-LIDAR tracking and adaptive motion planning to address the problems outlined in [8]. The environment is represented using a dynamic occupancy grid, while moving entities are detected through clustering techniques, followed by real-time tracking and prediction using a Kalman filter [9]. Moreover, we propose a motion planning approach that is cost-driven and enables autonomous vehicles to swiftly adapt to alterations in the environment with maximum safety and efficiency [10].

2. Context and Problem Formulation

The urban environment is an arena of unpredictability, posing dynamic challenges to an autonomous navigation system in a car. Some of the major dynamic challenges include tracking all the surrounding moving elements, adapting to changes in the environment, constraints on data processing, and collision avoidance. Dynamic tracking involves detecting and following multiple moving elements; this task is extremely important for the safety of an autonomous vehicle [11]. Achieving high accuracy and continuity of tracking such elements in real-world conditions is an uphill task [12]. Frequent updating of autonomous vehicle paths in urban environments is required due to changing traffic patterns, new road signage, and unpredictable behaviors by other road users. This type of real-time path adjustment is very important for safe navigation [13]. The computational burden of processing high-resolution data from several LIDAR sensors in real-time adds complexity to this challenge and demands effective algorithms [14]. Finally, collision avoidance is the task that stands out as the most important for autonomous vehicles. The vehicle needs to make decisions swiftly, including changes in its path to avoid collisions, even in very dense and complicated traffic [15].

3. Solution and Methodology

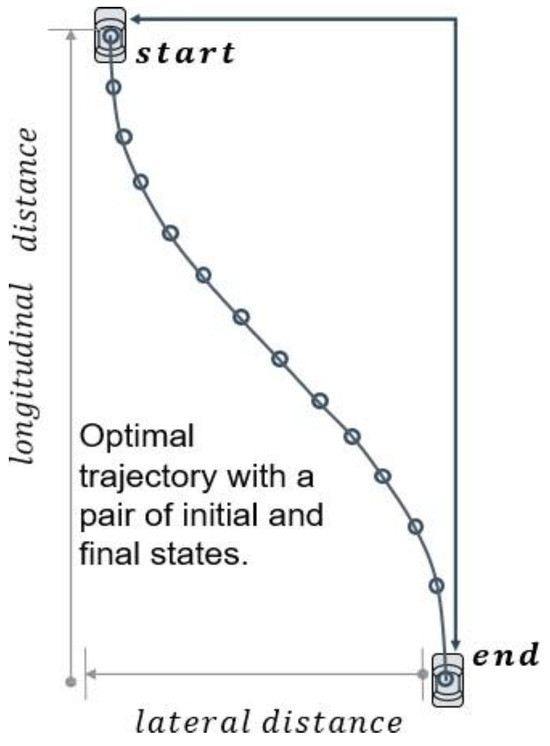

This part focuses on the problems pertaining to real-time motion planning in complex and dynamic environments where traditional methods are likely to be ineffective and less safe [16]. The vehicle can make optimal choices of trajectories that minimize risks and enhance performance, as it incorporates advanced techniques such as dynamic occupancy grid mapping, Kalman filtering, and Frenet coordinates. The Franco system can garner substantial benefits from the use of advanced filtering within s(t), where the quintic polynomial is defined to model the motion of a vehicle through a reference path (Refer to Figure 1). The quintic polynomial is given in the following form:

5

s(t) = ∑ aiti

i= 0

s(t) = ∑ aiti

i= 0

Figure 1.

Trajectory in Frenet coordinates using a quintic polynomial.

This polynomial provides assistance in controlling the position and velocity, as well as the acceleration, to ensure motion is smooth and continuous at all times. The coefficients ai (i = 0 to 5) are calculated based on the boundary conditions located on the two ends of the trajectory. This smoothness is vital, as it avoids jolts in motion and, in turn, assists in making the systems safe and efficient to operate within dynamic environments. Furthermore, the movement of “jerk”, in the proceedings, is the rate of change in acceleration, and “snap”, in the proceedings, is the rate of change in jerk, which are essential for making vehicle motion even smoother and more comfortable. To ensure comfort, these “higher order” derivatives are essential for loosening the constraints of the trajectory and providing comfort or less agitation and instability (Refer to Figure 1).

The suggested model uses multiple LIDAR sensors to create an active occupancy grid that models the environment using free and occupied spaces. As the vehicle moves and new data comes in, the grid is updated. Clustering methods, such as DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise), are used in order to segment the LIDAR dataset and capture components that are dynamic. The element is then refined perpendicular to extraction through a Kalman filter, which is a sensor fusion technique, to improve the position and velocity of a target by using current observation of the device and past locations of that device [17]. This is the way to demonstrate the predictive model of the Kalman filter, with the following formula:

where xk is the predicted state at time k, A is the state transition matrix, B is the control input matrix, uk represents control variables (such as velocity or steering angle), and wk is process noise. This approach enables accurate trajectory prediction, facilitating proactive motion planning [18].

xk = Axk−1 + Buk + wk

For motion planning, the system continuously evaluates possible trajectories using a cost function that balances safety, comfort, and efficiency. The cost function is defined as follows:

where Jlong and Jlat are the longitudinal and lateral jerks, representing abrupt changes in acceleration, Pc is the collision probability, s˙ is the current speed, s˙limit is the maximum allowable speed, and α, β, γ, and δ are weighting coefficients [19]. By minimizing this cost function C, the algorithm selects an optimal path that prioritizes safety and smoothness while maintaining efficiency, ensuring that the autonomous vehicle can quickly adapt to changes in the environment [20,21].

C = α · Jlong + β · Jlat + γ · Pc + δ · (s˙ − s˙limit)2

Several key components were carefully adjusted and integrated to improve situational awareness as well as motion prediction in complex urban scenes. The DBSCAN clustering algorithm was used to separate LIDAR point cloud data into static and dynamic parts. The parameters for detecting objects at the scale of a city were chosen empirically, with ε = 0.35 m for the neighborhood radius and minPts = 6 for the minimum cluster size. These values make a good compromise between being able to identify middle-sized dynamic agents (like pedestrians and cyclists) correctly and being robust regarding sensor noise. A linear Kalman filter for object tracking under a constant-velocity motion model was applied. The state vector contains position and velocity. The process and measurement noise covariance matrices were set to Q = 0.01·I4 and R = 0.05·I2, respectively, in a manner in which stability and responsiveness are balanced with each other. Trajectory generation is governed by a cost function that combines longitudinal and lateral jerk (Jₗₒₙ, Jₗₐₜ), predicted collision probability (Pc), and speed deviation from the desired target ((s˙ − s˙limit)2). These terms are weighted by α, β, γ, and δ. Relative weighting factors determined by sensitivity analysis for optimal values of weights resulted in α = β = 1.0, γ = 3.0, and δ = 0.5. This provided the following conclusions: more γ values result in better collision avoidance but more conservative behavior; lower α and β values increase jerk and worsen motion comfort. Performance offered a tradeoff between safety, comfort, and efficiency in dynamic environments.

4. Simulation and Results

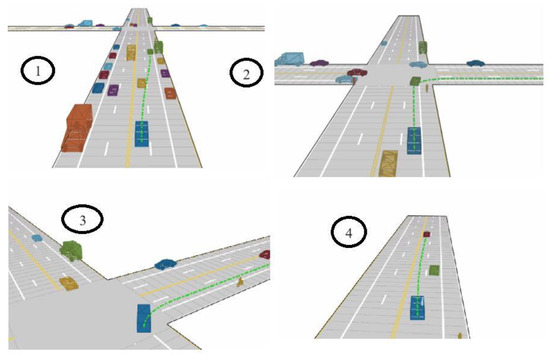

The system had to be validated by simulating urban areas with high traffic, crosswalks, and traffic lights. During every stage of the simulation, the algorithm for planning attempts to propose possible maneuvers for the ego vehicle that correspond to its current position and the desired end states. These actions are based on the topology of the road and the movement intention of the vehicle, which may include keeping the speed constant or overtaking another vehicle. The method of creating such paths caters to smooth trajectory generation via 5th order polynomial approximations, as shown in the Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Trajectory generation example.

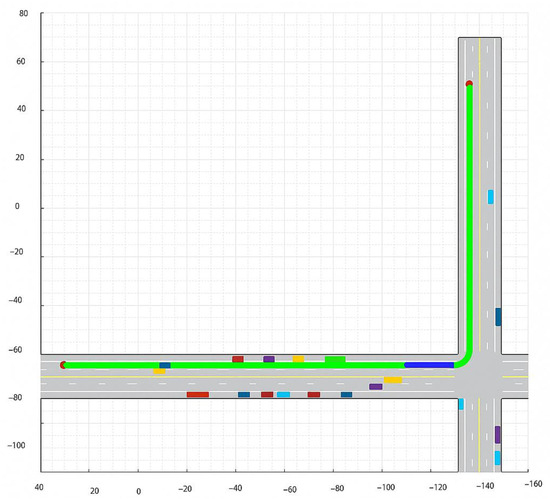

The output of the local path-planning algorithm is scrutinized to comprehend how the map predictions supported the vehicle guidance. The animation reveals how the autonomous vehicle maneuvered around dynamic obstacles and successfully reached its goal. The automobile also changed its typical behavior at some critical points; for example, it stopped at crossroads. This occurred as a result of the shifts that happened in the regional sampling policy. These alterations guaranteed that the vehicle was able to change its heading as well as actively respond to the surrounding environment, as the Figure 3 illustrates.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive visualization of ego vehicle path planning and adaptive behavior.

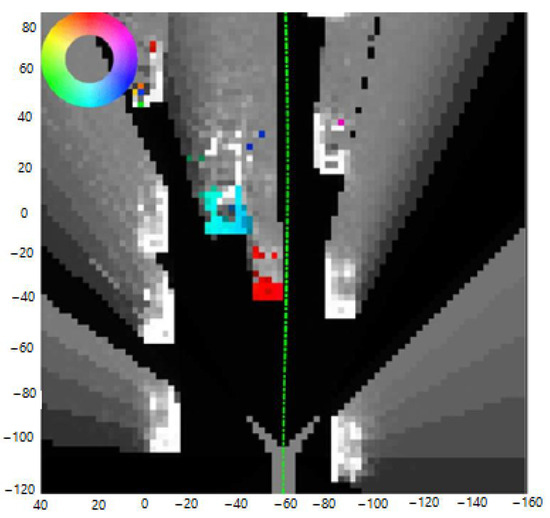

In Figure 4, the skeleton of a grid structure, termed a dynamic occupancy grid, is shown, whereby every color is indicative of the movement direction of the corresponding objects within the environment. The red cells encode objects (for example, the car in front of the ego vehicle), which are moving in a negative direction with respect to the abscissa axis; other colors, like violet and blue, are indicative of motion in different directions. The color coding is critical to learning the movement patterns around the vehicle, which has to be taken into consideration so that the system can maneuver within the ever-changing traffic situation.

Figure 4.

Dynamic occupancy grid showing object movement directions.

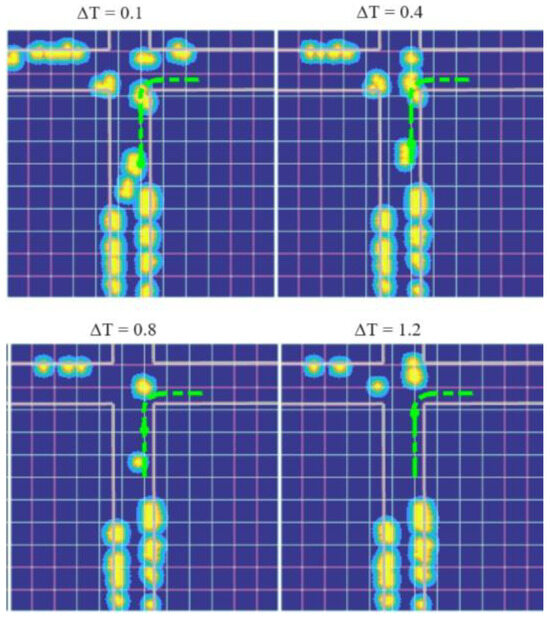

In Figure 4, the starting path of the ego vehicle crosses areas marked as occupied, which may, in turn, indicate a collision through the conventional static validation process. However, in an actively occupied space, the dynamic virtual occupancy adjusts via prediction of the movements of the neighboring objects. Red zones denote danger from collision, while blue denotes safety. With the passing of time, the car in front moves forward on the map, while stationary objects remain where they are. Figure 5 shows snapshots at 2.5 s, thus confirming the nature of collision-free parking of the ego vehicle in real-time motion.

Figure 5.

Predicted movement of dynamic obstacles in the cost map.

In addition to those results, extensive simulations in different urban environments were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the trajectory planning system. The results of the simulation prove that this trajectory planning system can be effective in extremely dynamic urban environments where the obstacles themselves are in motion. The simulations were performed in MATLAB (version R2022a), allowing real-time modeling and visual output of vehicle movement over a dynamic urban landscape. In all the simulations with moving obstacles (pedestrians and moving vehicles), the system, having been informed of the necessity, came up with new paths for the vehicle to avoid any potential collision. One of the simulations includes an intersection with pedestrians, and the vehicle slows down. In another simulation, the vehicle in front applies brakes, and then the trajectory of the vehicle is adjusted. The table below (Table 1) gives a summary of probability of collisions, reaction times, and what was performed under different conditions:

Table 1.

Collision probability and actions taken.

The simulation results validate the efficacy of the trajectory planning system for an autonomous vehicle in complex urban environments containing dynamic obstacles. Furthermore, the system also ensured smooth motion by minimizing jerk, since the system output showed low values for longitudinal and lateral jerk. The latter condition enhances a much more comfortable ride. The graph of variation with time is shown below (Table 2).

Table 2.

Longitudinal and lateral jerk over time.

To benchmark the performance of the proposed multi-LIDAR dynamic planning system, comparative experiments were run against a classical baseline: A* path planner + PID tracking controller. This baseline runs on static occupancy grids and does not predict dynamic agents as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Quantitative comparison with baseline methods.

Our approach makes a cut of about 65% in hit chance and a 38% betterment in response time compared to the baseline. Also, the lower jerk values show smoother vehicle paths, while the higher replanning rate highlights the system’s improved flexibility to fast changes in surroundings.

5. Limitations of the System and Challenges in the Environment

Although the results of the simulation are promising, there are several challenges to applying the proposed multi-LIDAR dynamic planning system to actual environments. Noise from the sensors and factors relating to the environment adversely affect the quality of LIDAR data. In conditions such as fog, rain, or snow, feasible object detection and occupancy estimation become weak. Therefore, robust multi-sensor fusion with more complementary modalities, angular radar and cameras, is needed to enhance the reliability of the system. Furthermore, occlusion of important dynamic agents, smaller vehicles or pedestrians, by big static or sometimes even moving obstacles is one more problem in object tracking as well as motion prediction, usually leading to late detections or misses of these targets, particularly within complex urban scenarios. Also, the real-time multi-LIDAR point cloud processing, dynamic clustering, prediction, and adaptive motion planning are very computationally heavy. Thus, further optimization is needed in the whole processing pipeline, especially in embedded platforms with resource constraints, to keep the system responsive and scalable [22].

6. Conclusions

This research proposes an integrated approach for improving the navigation of autonomous vehicles (AVs) in urban environments through multi-LIDAR tracking with LIDAR-enabled adaptive motion planning. The system we have developed has demonstrated significant effectiveness in safety, adaptability, and real-time responsiveness in simulations of active cityscapes. The system collects real-time data through multiple LIDAR sensors mounted on the vehicle to track various dynamic obstacles in the environment. These objects are monitored and anticipated, which allows the automobile to alter its course to prevent crashes while maintaining effectiveness. Real-world verification has to be performed to evaluate the system’s performance in uncontrolled and more difficult settings with elevated levels of sensor sound and unpredictable human behavior.

Apart from real-world testing, further work will also incorporate more sophisticated machine learning algorithms, like reinforcement learning, for improved trajectory prediction and decision-making. There also needs to be further work to increase the system’s robustness against severe weather and lighting conditions for larger adoption of autonomous driving systems. Also, the ability to integrate data from other sensors, including cameras and radar, has the potential to increase the vehicle’s environmental understanding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and M.A.Y.; methodology, M.B. and M.A.Y.; software, M.B.; validation, M.B., M.A.Y., R.D., M.E.W. and Y.E.K.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, M.B.; resources, M.B. and M.A.Y.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, M.B.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, M.A.Y. and R.D.; project administration, M.B. and M.A.Y.; funding acquisition, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lee, G.; Kim, S.; Seo, D.; Kang, Y. Inverse Reinforcement Learning with Dynamic Occupancy Grid Map for Urban Local Path Planning: A CNN Model Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 15 July 2024; pp. 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, K.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.Y.; Zhang, W.; Yu, H. DORF: A Dynamic Object Removal Framework for Robust Static LiDAR Mapping in Urban Environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 7922–7929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kästner, L.; Zhao, X.; Shen, Z.; Lambrecht, J. A Hybrid Hierarchical Navigation Architecture for Highly Dynamic Environments Using Time-Space Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration (SII), Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–20 January 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrabi, N.; Fesharakifard, R.; Menhaj, M.B. Dynamic reconfiguration of costmap parameters with Fuzzy controllers to enhance path planning. In Proceedings of the 2022 10th RSI International Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics (ICRoM), Tehran, Iran, 22–24 November 2022; pp. 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.C. Safe Navigation of a Non-Holonomic Robot with Low Computational-power in a 2D Dynamic Environment. In Proceedings of the 2022 Australian & New Zealand Control Conference (ANZCC), Gold Coast, Australia, 5 December 2022; pp. 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, S.; Yin, H.; Ang, M.H. Exploring the Effect of 3D Object Removal using Deep Learning for LiDAR-based Mapping and Long-term Vehicular Localization. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Macau, China, 8–12 October 2022; pp. 1730–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Kobayashi, Y.; Arjonilla, F.J.; Nagasaka, S.; Koike, M. Evaluation of mapping and path planning for non-holonomic mobile robot navigation in narrow pathway for agricultural application. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration (SII), Iwaki, Fukushima, Japan, 11–14 January 2021; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mashhadani, Z.; Mainampati, M.; Chandrasekaran, B. Autonomous Exploring Map and Navigation for an Agricultural Robot. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Control and Robots (ICCR), Tokyo, Japan, 26–29 December 2020; pp. 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghmara, H.; Boudali, M.-T.; Laurain, T.; Ledy, J.; Orjuela, R.; Lauffenburger, J.-F.; Basset, M. Obstacle Avoidance, Path Planning and Control for Autonomous Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Paris, France, 09–12 June 2019; pp. 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhuang, M.; Zhong, X.; Wu, W.; Liu, Q. RSPMP: Real-time semantic perception and motion planning for autonomous navigation of unmanned ground vehicle in off-road environments. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 4979–4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, Y.; Liu, Z. OccFusion: Depth Estimation Free Multi-sensor Fusion for 3D Occupancy Prediction. In Computer Vision–ACCV 2024. ACCV 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Cho, M., Laptev, I., Tran, D., Yao, A., Zha, H., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 15481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Duan, H.; Ding, Y.; Xiao, X.; Yuan, J. Scene reconstruction techniques for autonomous driving: A review of 3D Gaussian splatting. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Quadrotor Trajectory Tracking and Simultaneous Localization and Mapping Implementation in CoppeliaSim. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. C 2024, 106, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburaya, A.; Selamat, H.; Muslim, M.T. Review of vision-based reinforcement learning for drone navigation. Int. J. Intell. Robot Appl. 2024, 8, 974–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Dhara, B.C. 3D LiDAR-based obstacle detection and tracking for autonomous navigation in dynamic environments. Int. J. Intell. Robot Appl. 2024, 8, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, M.; Youssefi, M.A.; Dakir, R.; El Wafi, M. Enhancing the PRM Algorithm: An Innovative Method to Overcome Obstacles in Self- Driving Car Path Planning. Int. Rev. Autom. Control (IREACO) 2024, 17, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.H.; Nejat, G. Enhancing Robot Task Completion Through Environment and Task Inference: A Survey from the Mobile Robot Per- spective. J. Intell. Robot Syst. 2022, 106, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahani, A.; Ech-Chhibat, M.E.; Samri, H.; Zahiri, L.; Mansouri, K. Intelligent Cutting Force Control by a Cooperative Multi-Robot System: Modeling and Simulation in a Milling Application. Int. J. Eng. Appl. (IREA) 2024, 12, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.L.; Hoang, G. Path Tracking Algorithm with Wheel Radii Estimation for Automatic Guided Vehicle Based on Adaptive Backstepping Control Method. Int. J. Eng. Appl. (IREA) 2024, 12, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zourari, A.; Youssefi, M.A.; Youssef, Y.; Dakir, R. Reinforcement Q-Learning for Path Planning of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Unknown Environments. Int. Rev. Autom. Control (IREACO) 2023, 16, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Wafi, M.; Youssefi, M.A.; Dakir, R.; Bakir, M. Intelligent Robot in Unknown Environments: Walk Path Using Q-Learning and Deep Q-Learning. Automation 2025, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-Y.; Vasudevan, R.; Johnson-Roberson, M. Occlusion-Aware Risk Assessment for Autonomous Driving in Urban Environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 2235–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).