Abstract

The paper discusses the economic and infrastructural challenges preventing the adoption of Electric Vehicles (EVs) in Pakistan. It focuses on key factors such as affordability, consumer preferences, and the overall readiness of the market. Based on a segment-wise comparison, the analysis reveals that four-wheeler EVs carry an initial price premium of 20 to 64 percent over internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, with payback periods ranging from 11 to 25 years, placing them out of reach for most middle-income consumers. In contrast, electric two- and three-wheelers—comprising more than 90 percent of registered vehicles—offer a significantly more practical and affordable pathway for mass adoption. These vehicles exhibit minimal upfront cost differences, annual operational savings exceeding PKR 62,000, and short payback periods of just 4 to 6 months, making them highly feasible in the local context. The study adopts a mixed-methods approach using national price data, vehicle registration records, and international case studies from India, Kenya, and Norway. It evaluates financing innovations such as battery leasing, concessional green loans, and carbon-credit-linked microfinance, and outlines a consumer-focused policy framework that emphasizes financial inclusion, decentralized infrastructure development, and phased implementation strategies. By aligning global lessons with Pakistan’s socioeconomic and infrastructural realities, the paper offers a scalable and inclusive roadmap for accelerating EV adoption through targeted, consumer-driven solutions.

1. Introduction

The global transition toward electric vehicles (EVs) is driven by a combination of environmental concerns, rising fuel costs, energy insecurity, and the rapid advancement of clean technologies. In 2024, global EV sales were projected to reach 17 million units, representing nearly 20 percent of all new vehicles sold [1]. Governments across developed and developing economies are now implementing targeted incentives, investing in infrastructure, and enforcing emission regulations to accelerate the adoption of EVs.

Within this global context, the transition to EVs has taken on critical importance for developing countries like Pakistan. The transportation sector in Pakistan is among the largest contributors to energy consumption, accounting for over 40 percent of national oil use. It is also a leading source of urban air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. For instance, in the first two months of FY2024–25, Pakistan’s oil import bill surged by 23 percent to USD 2.53 billion compared to the same period the previous year [2]. Simultaneously, major cities such as Lahore have recorded extreme levels of air pollution, with the Air Quality Index (AQI) exceeding 1100 in November 2024, far beyond the hazardous threshold [3]. These alarming trends underscore the urgency of moving toward sustainable transportation solutions.

Recognizing this urgency, the Government of Pakistan introduced the National Electric Vehicle Policy (NEVP) in 2019. This policy offered tax incentives, reduced import duties, and encouraged local manufacturing to stimulate the EV market. More recently, the government has launched the New Energy Vehicle (NEV) Policy. This policy outlines an ambitious roadmap to increase EV penetration to 30 percent of all new vehicle sales by 2030, while also aiming for complete decarbonization of the transport sector by 2060. These policy initiatives reflect a strong national commitment. The introduction of the NEV Policy marks a significant step forward and signals renewed momentum in the sector. However, challenges remain. Consumers continue to face high upfront costs, limited charging infrastructure, and minimal access to financing. Additionally, there is a lack of awareness and after-sales service, particularly in smaller cities and rural areas. These barriers continue to hinder widespread EV adoption in the country.

As a result, there is a growing need to understand not only the technical and environmental dimensions of EV adoption but also the economic, financial, and social factors that determine feasibility at the local level. Therefore, this paper seeks to qualitatively assess the categories of barriers to EV adoption in Pakistan in a consumer-based perspective by considering, specifically, the cost factor, access to financing, and the readiness of the infrastructure. It focuses on analyzing two- and three-wheelers as an entry point and building a systematic structure that considers not only the country but also the best practices across the world.

Significance of Study

The study holds the significance of understanding the critical components through systemic and internal factors that affect electric vehicle (EV) adoption in emerging economies, with a particular focus on Pakistan. Despite the favorable policy landscape, the constraints of the economy, especially the high purchase cost of electric vehicles, become an overriding barrier for the majority of consumers, particularly those from low- and middle-income groups. High upfront costs have been consistently identified as a major impediment in developing countries, where financial support mechanisms are often limited [4]. Placing the issue of two- and three-wheelers front and center, the study locates the scalable and context-sensitive entry point to electrification, which can appropriately interface with the current patterns of mobility. The prior literature highlights that adaptation of EVs in such segments is critical for accelerating adoption in developing regions [5]. The study also examines consumer financing gaps, noting that innovative financial instruments, including climate finance and carbon market incentives, are needed to stimulate demand. Furthermore, the research presents the geographical inequalities in charging infrastructure and proposes its decentralization and integration with renewable energy sources to ensure equitable access. This synergized framework provides valuable insights into policymakers and development practitioners aiming to create inclusive, consumer-based, and sustainable EV transition pathways in the Global South.

2. Methodology

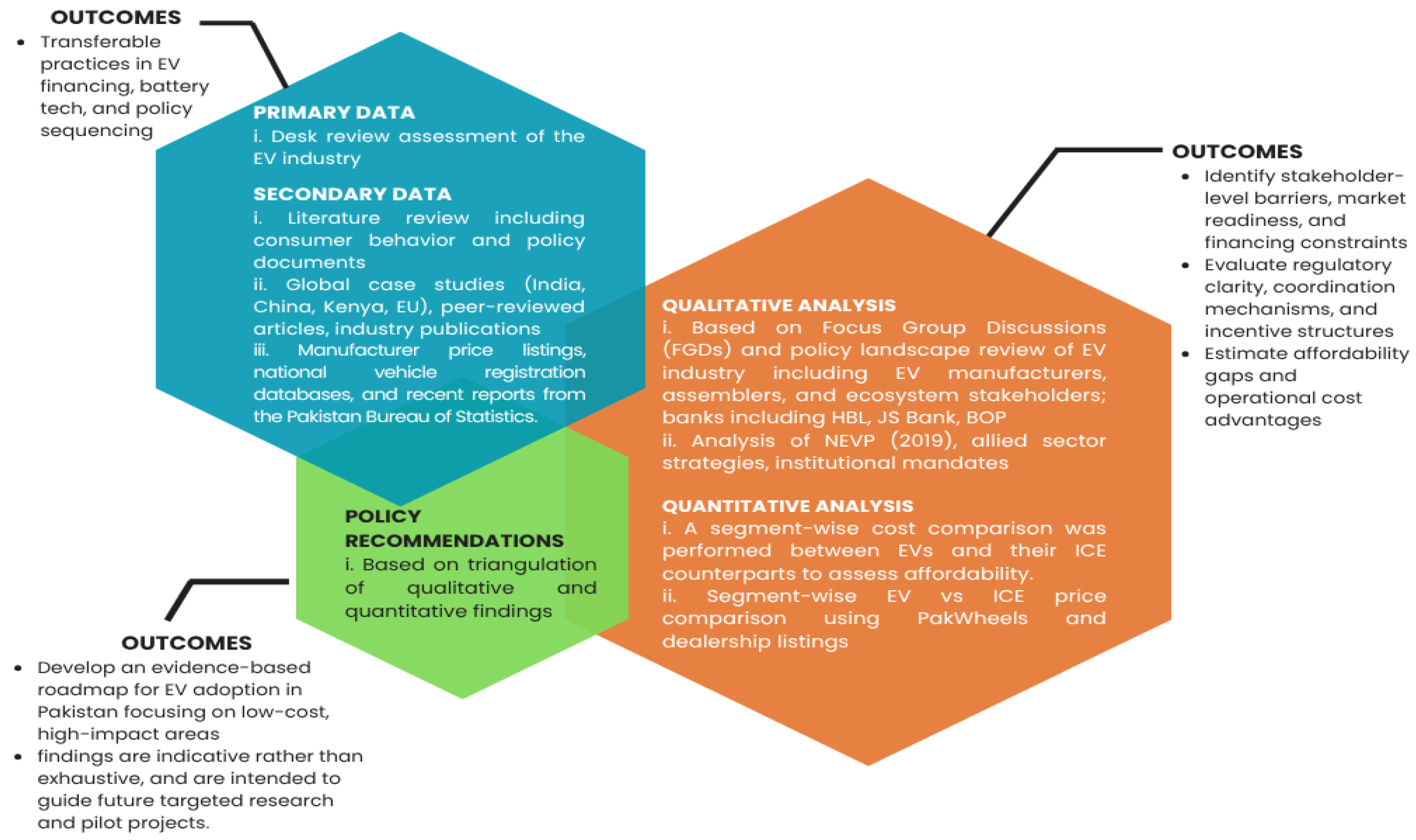

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, integrating both qualitative and quantitative techniques to investigate the economic, infrastructural, and financial barriers to electric vehicle (EV) adoption in Pakistan as shown in Figure 1. Given constraints in accessing primary datasets, the research primarily relies on secondary data selected based on relevance, credibility, and recency. These sources include manufacturer and dealership price listings (e.g., PakWheels, OLX), national registration data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics and Excise Departments, policy documents such as the National Electric Vehicle Policy (2019) and the New Energy Vehicle Policy, and the peer-reviewed literature and global case studies from India, China, Kenya, and the European Union. Complementing these, limited primary data was obtained through desk-based expert interviews and informal policy analysis sessions involving stakeholders from EV manufacturing, financial institutions (e.g., HBL, JS Bank), and government agencies. The analysis included a segment-wise cost comparison of EVs and internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles across multiple categories—entry-level compact cars, sedans, SUVs, and two- and three-wheelers—using dealership prices and consumer platforms. The study also reviewed financing mechanisms and policy strategies through international benchmarks such as India’s FAME II and Kenya’s carbon-credit microfinance models. However, the methodology is subject to limitations. The absence of primary field data and comprehensive consumer surveys restricts the granularity of behavioral insights and usage patterns. Moreover, lifecycle cost analysis could not be conducted due to insufficient operational data. Consequently, the findings are indicative rather than exhaustive, designed to guide further research, policy experimentation, and pilot interventions.

Figure 1.

Snapshot of the paper’s methodology.

3. Results

This study finds that while electric vehicles (EVs) hold long-term environmental and economic benefits, their adoption in Pakistan remains limited by significant affordability and infrastructure constraints. A detailed cost comparison across different vehicle types reveals that four-wheeler EVs remain economically unviable for most consumers due to high upfront costs and long payback periods, while two- and three-wheelers present a far more accessible and scalable opportunity. This section presents results across three dimensions: upfront cost comparisons, operational savings, and payback periods—with a particular focus on the case for mass electrification of two- and three-wheelers.

A key constraint to EV penetration is the higher upfront cost relative to ICE vehicles, which is a major determinant for price-sensitive consumers. Segment-wise comparisons reveal that electric vehicles are 20% to 64% more expensive than their gasoline counterparts, with the largest disparities observed in the compact SUV and mid-range SUV categories. Table 1 summarizes these differences.

Table 1.

Segment-wise ICE vs. EV Ownership Comparison between ICE & EV Cars.

As shown in Table 1, price differentials are exacerbated by limited financing options, import duties, and the high cost of lithium-ion batteries, which continue to restrict access for middle- and lower-income consumers [6]. While operational savings and lower maintenance costs provide long-term benefits, they are often insufficient to overcome the financial burden of the initial investment, particularly in the absence of widespread credit facilities or leasing mechanisms.

While it is often argued that EVs deliver operational savings through reduced fuel and maintenance costs, this benefit varies substantially by vehicle segment. When calculating five-year ownership costs based on segment-specific mileage (ranging from 8 to 22 km/L for ICEs) and electricity rates of PKR 39/kWh for EVs, the operational savings become clearer. Table 2 shows that EVs can save between PKR 1 to 4.6 million in running costs over five years, depending on the ICE vehicle being replaced.

Table 2.

5-Year Operational Cost Comparison—ICE vs. EV (4-Wheelers).

However, these long-term savings do not necessarily justify the high upfront cost, particularly for middle-income consumers. As shown in Table 3, the payback period for entry-level compact cars is over 11 years, while mid-range sedans and SUVs exceed 20 years. Only luxury SUVs achieve a relatively shorter payback of around 16 years. This reinforces the notion that, without targeted incentives or financing support, four-wheeler EVs remain out of reach for the majority of Pakistan’s population.

Table 3.

Payback Period—ICE vs. EV (4-Wheelers).

In contrast, electric two- and three-wheelers offer a more affordable and scalable route to electrification. With over 90% of registered vehicles in provinces like Punjab comprising motorcycles and rickshaws, this segment presents an accessible entry point for millions of daily commuters and small business operators. As shown in Table 2, price differences between EV and ICE models in this category are relatively modest—ranging from PKR 7000 to 27,000 (USD 30 to 100)—making electrification more economically viable.

Table 4 shows that despite the marginally higher costs, electric two-wheelers deliver substantial operational cost savings due to lower fuel and maintenance expenses. Furthermore, their compatibility with home charging and battery swapping models reduces infrastructure dependency, enhancing feasibility even in regions with limited charging stations.

Table 4.

ICE vs. EV Price Comparison—Two-Wheelers.

More importantly, the operational cost benefits are immediate and substantial. As shown in Table 5, the annual fuel and maintenance savings from switching to an electric two-wheeler can exceed PKR 62,000. This makes electrification not just an environmentally responsible choice, but an economically smart one.

Table 5.

Annual Operational Cost and Savings—ICE vs. EV (2-Wheelers).

Due to these high savings and relatively low initial price difference, the payback period for electric two-wheelers is remarkably short. Table 6 shows that the cost difference can be recovered in as little as 4.1 months for the Jolta JE-70D, and around 6 months for the Evee Nisa.

Table 6.

Payback Period—ICE vs. EV (2-Wheelers).

Therefore, while four-wheeler EVs continue to face major affordability and financing challenges in Pakistan, electric two- and three-wheelers offer a practical and economically sound entry point for mass EV adoption. Their compatibility with home charging, alignment with current transportation patterns, and short financial payback periods make them a viable path forward for both consumers and policymakers seeking an inclusive and scalable transition to electric mobility.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal that Pakistan’s transition to electric vehicles is constrained not only by affordability but also by gaps in infrastructure, financing, and institutional alignment. However, within these constraints lie targeted opportunities, particularly through the electrification of two- and three-wheelers, which represent the most viable entry point for large-scale EV deployment in the country.

4.1. Affordability Dynamics and Market Segmentation

The segment-wise analysis underscores a persistent affordability gap between EVs and internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. Four-wheeler EVs remain prohibitively expensive, with prices often exceeding their ICE counterparts by 40% to 64%, depending on the vehicle category. For instance, the compact SUV segment shows a price differential of PKR 5.09 million, while mid-range SUVs cost PKR 6 million more than their ICE equivalents. Although EVs offer operational savings—up to PKR 4.6 million over five years in the luxury SUV segment—the average payback period ranges from 11 to 25 years, which is far beyond the financial planning horizon of most middle-income Pakistani consumers. This cost premium is particularly acute in the compact and mid-range SUV categories, where the average consumer also lacks access to low-interest loans, vehicle leasing options, or residual value guarantees. Consequently, EV adoption in the four-wheeler category remains restricted to niche, high-income consumers with greater purchasing power and risk tolerance.

In comparison, the electrification of two- and three-wheelers demonstrates immediate economic viability. These vehicles show marginal price differences, with electric models costing only PKR 21,000 to 31,000 more than their ICE counterparts. Despite the slightly higher upfront cost, they offer substantial annual operational savings of PKR 62,050, resulting in payback periods as short as 4 to 6 months. Given that two- and three-wheelers account for over 90% of registered vehicles in provinces like Punjab, targeting this segment represents a highly scalable and inclusive strategy for mass electrification. Their relatively low battery capacity requirements and compatibility with household charging infrastructure also reduce dependence on the national grid, making adoption more feasible in both urban and peri-urban environments.

4.2. Financial Mechanisms and Inclusion Challenges

One of the most significant barriers to EV adoption is the lack of structured financing mechanisms tailored to low-income and informal-sector users. Conventional vehicle loans are often inaccessible due to weak credit histories and rigid collateral requirements. While several commercial banks in Pakistan have initiated pilot EV financing schemes, these remain limited in scale and are not designed for high-volume, low-margin two-wheeler segments [7].

Battery leasing has emerged as a promising alternative that can significantly lower the financial barrier to EV ownership. Since the battery typically accounts for 35 to 40 percent of an electric vehicle’s total cost, removing this component from the purchase equation through leasing could reduce upfront prices by approximately 30 to 35 percent. For example, an electric two-wheeler priced at PKR 150,000 could be made available for closer to PKR 100,000 under a battery leasing arrangement, bringing it in line with conventional ICE motorcycles. However, successful implementation requires a national framework for battery standardization, a scalable battery-swapping infrastructure, and backend logistics management—none of which currently exist in Pakistan. These operational prerequisites present significant deployment challenges, particularly outside major cities.

Green loans—offered at below-market interest rates or supported through government subsidies—could also bridge the affordability gap. A green loan program with a 5% interest rate and a 3-year term could reduce monthly payments by up to 40% compared to traditional loans. Yet, the financial sector in Pakistan faces difficulties in extending such credit to informal workers due to verification, collateral, and default risk concerns. Drawing from India’s FAME-II scheme, which successfully bundled consumer incentives with partial risk guarantees, Pakistan could develop a hybrid financing mechanism that combines concessional green loans with credit guarantees backed by public or donor funding [8].

Additionally, carbon credit-linked microfinance, as demonstrated in Kenya, can offer small-scale financing to low-income consumers while enabling access to international climate finance. Under this model, verified emissions reductions from EV adoption are monetized and reinvested into consumer financing pools. While theoretically appealing, this approach would require Pakistan to strengthen its carbon credit registry, create transparent verification systems, and establish intermediaries capable of aggregating and selling emissions reductions at scale.

To ensure scalability, these financial innovations must be supported by coordinated policy action, capacity-building in the financial sector, and digital systems that reduce transaction costs. Without these structural supports, even well-designed financing tools may fail to reach the intended user base.

4.3. Infrastructure Readiness and Energy Constraints

Infrastructure remains a core challenge in Pakistan’s EV transition. Current charging networks are underdeveloped and spatially uneven, concentrated primarily in metropolitan areas. Moreover, the national grid’s vulnerability—marked by load-shedding, transmission losses, and fossil-fuel dependency—raises concerns about the reliability of EV charging, especially for larger vehicles requiring high-voltage fast chargers.

However, two- and three-wheelers again offer a more flexible pathway. These vehicles can be efficiently charged via low-voltage AC outlets or battery swapping stations that do not rely heavily on grid upgrades. The global success of battery-swapping infrastructure—particularly in India, China, and Taiwan—demonstrates its value in minimizing range anxiety and downtime for commercial fleets [9]. In Pakistan’s context, integrating such decentralized charging models with renewable energy sources, such as rooftop solar, can reduce grid stress while ensuring operational continuity.

4.4. Policy Implementation and Institutional Coordination

Global experiences demonstrate that successful EV transitions require not only robust policies but also synchronized execution across government, industry, and civil society. This study references India, Kenya, and Norway as comparative cases because each offers contextually relevant insights at different development stages: India represents a regional peer with similar socio-economic dynamics and high two-wheeler reliance; Kenya illustrates the use of innovative financing mechanisms like carbon credit-linked microfinance in a resource-constrained, low-income environment; and Norway provides a global best-case model of mature policy integration for long-term EV penetration.

In India, the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles (FAME) program has combined multiple instruments—including upfront purchase subsidies, charging infrastructure development, and production incentives—to create a comprehensive EV ecosystem. The FAME-II phase placed special emphasis on two- and three-wheelers and electric public transport, aligning directly with Pakistan’s vehicle landscape. Crucially, India’s bundling of subsidies with credit guarantees for consumers and local manufacturing support has enabled wider affordability, offering a replicable roadmap for Pakistan to follow in a segmented and phased manner.

Kenya, by contrast, has innovated on the financing side by integrating EV deployment with carbon markets. Through verified emissions reductions, Kenya has monetized the environmental benefits of EVs to fund microloans and pay-as-you-go battery models. This approach is particularly relevant for Pakistan, where conventional financing is inaccessible for informal workers. However, implementing such a model would require Pakistan to establish a verifiable carbon credit registry and transparent aggregation systems—elements that remain underdeveloped.

Norway exemplifies how long-term consistency, and holistic planning can accelerate EV transition. Its policies eliminated VAT on EVs, provided toll and parking exemptions, invested in high-density fast charging, and ensured wide public engagement. While Norway’s fiscal capacity and consumer base differ significantly from Pakistan’s, the core lesson lies in aligning fiscal tools, regulatory enforcement, and public–private partnerships. For Pakistan, these lessons reinforce the need for coordinated institutional reform and a reliable incentive delivery mechanism.

For Pakistan, a phased and segmented approach will be key. Prioritizing electrification in high-penetration vehicle segments such as motorcycles and rickshaws can deliver rapid results. Supporting this transition through incentives for local assembly, battery recycling systems, and low-interest consumer financing can help bridge current market gaps. Furthermore, policy coherence across transport, energy, industry, and finance sectors is essential to align infrastructure deployment, electricity tariffs, and investment incentives. Building a responsive institutional architecture that enables public–private collaboration, clear incentive delivery mechanisms, and accountability will determine the success of EV deployment in the coming years.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study finds that despite the presence of favorable government policies, Pakistan’s electric vehicle adoption remains limited due to high upfront costs, constrained financing options, and inadequate infrastructure. The segment-wise cost analysis revealed that four-wheeler EVs carry a price premium of 20 to 64 percent compared to internal combustion engine vehicles. Furthermore, the payback period for these EVs ranges between 11 and 25 years, which places them well beyond the affordability range for average consumers. These findings suggest that, under current conditions, four-wheeler electrification is unlikely to scale without significant financial and structural reforms.

On the other hand, the electrification of two- and three-wheelers emerges as a more viable and inclusive pathway. This segment, which accounts for over 90 percent of registered vehicles in provinces such as Punjab, demonstrates a far smaller cost differential and offers substantial operational savings. With average fuel and maintenance savings exceeding PKR 62,000 annually and a payback period as short as 4 to 6 months, electric two- and three-wheelers offer a compelling case for near-term adoption. Therefore, this study emphasizes the urgent need to channel policy attention and financial innovation toward this segment to achieve scalable electrification.

Moving forward, the analysis suggests several actionable strategies for policymakers. First, targeted financial mechanisms such as battery leasing, concessional green loans, and credit-guaranteed microfinance programs should be developed with a focus on informal sector consumers. Second, the deployment of decentralized, renewable-powered charging infrastructure—including battery swapping stations, should be prioritized in urban and peri-urban areas. Finally, international lessons from countries like India, Kenya, and Norway highlight the importance of integrating policy coordination, localized incentives, and infrastructure planning. If implemented strategically, these interventions can help Pakistan initiate a just and economically feasible transition to low-emission transport.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Q.; methodology, S.Z., S.Q. and A.I.; software, formal analysis, S.Z., S.Q. and M.Z.; data curation, analysis and discussion. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support received from the Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI). Also, we really appreciate the valuable inputs from Ubaid ur Rehman Zia and Khalid Waleed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- BloombergNEF. New Energy Outlook. 2024. Available online: https://about.bnef.com/insights/clean-energy/new-energy-outlook/ (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Khan, M.Z. Oil Imports Surge 23pc in July–August. Dawn, 17 September 2024. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1859454 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Record-High Pollution Sickens Thousands in Pakistan’s Cultural Capital of Lahore. AP News, 6 November 2024. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/pakistan-lahore-record-pollution-3bada25447094a3b1bd62d3be38b5984 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Mahal, K.; Patil, P. Electric Vehicles and India: Recent Trends in the Automobile Sector. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2021, 2, 661–668. [Google Scholar]

- Narassimhan, E.; Johnson, C. The Role of Demand-Side Incentives and Charging Infrastructure on Plug-in Electric Vehicle Adoption: Analysis of US States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 074032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, F. Electric Vehicles: Benefits, Challenges, and Potential Solutions for Widespread Adaptation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global EV Outlook 2025: Trends in Electric Car Affordability; IEA: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025/trends-in-electric-car-affordability (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Kohli, S. Electric Vehicle Demand Incentives in India: The FAME II Scheme and Considerations for a Potential Next Phase; International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT): Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: http://theicct.org/publication/electric-vehicle-demand-incentives-in-india-the-fame-ii-scheme-and-considerations-for-a-potential-next-phase-june24 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Guerra, M. Battery Swapping Market: CATL and Ample Lead Global Expansion. Battery Tech, 13 June 2025. Available online: https://www.batterytechonline.com/ev-batteries/battery-swapping-market-catl-and-ample-lead-global-expansion (accessed on 5 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).