Abstract

This study investigates the gendered implications of Pakistan’s Special Economic Zones (SEZs) under CPEC 2.0, focusing on risks and opportunities for women in the country’s green industrial transition. Using a mixed-methods approach that combines secondary research with multi-stakeholder consultations, including engagement with SEZ authorities, Chinese investors, and women’s professional networks, the paper examines how legal ambiguity, defeminization, and occupational segregation restrict women’s participation and mobility in SEZs. Drawing on global comparative evidence and Pakistan’s specific legal and institutional gaps, the paper argues that SEZs can support gender-equitable industrialization if reforms are integrated into their design and governance. It recommends introducing mandatory gender equity plans in zone licensing, providing targeted skills training for women in high-tech sectors, operationalizing Pakistan’s National Gender Policy Framework within SEZ development, and embedding the Zone Social Responsibility (ZSR) framework across all SEZs to ensure long-term inclusion and empowerment.

1. Introduction

Pakistan’s SEZs under CPEC are central to the country’s ambitions for industrial upgrading, technology localization, and export diversification. Positioned at the nexus of industrial policy and regional integration, these zones promise large-scale job creation, skills development, and foreign investment. However, this transformation remains incomplete without the deliberate integration of gender responsiveness as a foundational pillar of SEZ governance, infrastructure, and labor force strategy. While SEZs are heavily embedded in national development plans and CPEC priorities, gender equality is largely absent from their formal planning frameworks. This omission limits not only women’s participation in industrial value chains but also undermines the inclusive growth potential of the SEZ model.

Despite women constituting nearly half the population, their national labor force participation remains stagnant at 24%, with even lower rates in CPEC-linked sectors [1]. Without institutional mechanisms to address legal ambiguity, occupational segregation, and structural barriers, SEZs risk replicating global patterns where women are concentrated in low-skill, low-wage, and highly precarious work with minimal upward mobility. By treating the labor force as a neutral category, gender-neutral policies obscure unequal starting points and ignore the systemic disadvantages women face in accessing high-value industrial opportunities. Institutionalizing gender-responsiveness into SEZ development is therefore not only a social imperative but also a strategic economic necessity for inclusive green industrialization under CPEC as Pakistan seeks to diversify its industrial base and localize green technologies.

Globally, industrialization strategies are increasingly recognized as vehicles for women’s empowerment, but only if gender is deliberately mainstreamed. As UNIDO emphasizes, well-designed industrial policies “have the potential to decrease existing gender-based discrimination and become a tool for the empowerment of women”, whereas neglecting gender often means lost opportunities [2]. A World Bank report on Bangladesh’s EPZs finds that the most successful zones actively integrate three pillars of gender inclusion, fair working conditions for female staff, career advancement programs, and support for women entrepreneurs [3]. Yet such gender-forward planning remains the exception rather than the rule in most SEZ contexts.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the broader strategic framework under which CPEC operates, similarly lacks a gender-sensitive lens. As Yin and Shieh (2022) observe, although China officially promotes gender equality, the BRI “has no specific policy or serious discussion” on gender [4]. Given that most BRI projects are large-scale infrastructure, energy, or mining endeavors with long operational lifespans, they caution that “if BRI projects do not consider gender impacts throughout the project life cycle, they can reinforce gender inequalities for decades,” undermining both developmental outcomes and social equity. China could assume a leadership role within the Global South not only by exporting its own “valuable experience in achieving economic prosperity through women’s empowerment,” but also by ensuring that its state-owned enterprises and private firms adopt a “gender lens” when investing overseas. A gender-equitable approach to CPEC would thus reinforce the kind of “win–win” outcomes frequently championed by Chinese leadership [4]. For Pakistan, integrating gender considerations into CPEC SEZs is not only consistent with global best practices but also necessary to align with Pakistan’s own National Gender Policy Framework (2022).

This paper addresses a critical gap: the lack of Pakistan-specific analysis on the gendered risks of SEZ development. While there is no disaggregated SEZ employment data currently available in Pakistan, the literature and stakeholder consultations point toward likely risks of exclusion, defeminization, and occupational stratification if corrective action is not taken. The paper therefore aims to establish both the urgency and the policy rationale for gender-responsive SEZ governance.

2. Methodology

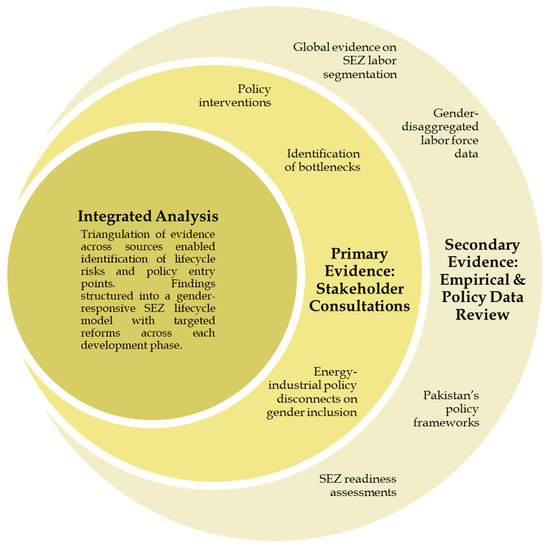

This study analyzes the gendered dynamics of SEZ development under CPEC 2.0, with a particular focus on opportunities and risks for women in Pakistan’s shift toward green industrialization. Recognizing the structural nature of gender segmentation in industrial employment, the study combines secondary data analysis with stakeholder consultations to triangulate findings and offer a grounded policy lens. An extensive desk review was conducted, drawing on government reports and academic literature on the social impacts of SEZs, gendered labor dynamics in industrial development, and employment patterns in energy transitions. This included analysis of the SEZ Act, the Pakistan’s National Gender Policy Framework, and labor laws. The review also draws on global evidence of gender outcomes in SEZs, studies on defeminization, and women’s participation in clean energy value chains. This review informed both the identification of gender-specific risks across the SEZ lifecycle and the design of recommended interventions. To validate and deepen the secondary findings, the study engaged approximately 30–40 stakeholders through focus group discussions, key informant interviews, and participation in high-level policy dialogues. Participants included SEZ authorities, and zone developers such as the Board of Investment (BoI), the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Economic Zones Development and Management Company (KPEZDMC), Chinese private sector representatives operating in energy and green manufacturing, policymakers from the federal and provincial levels, and members of professional networks such as Women in Energy Pakistan, which is a strategic partner of the World Bank’s WePower platform.

Two key events directly informed the consultation process:

- High-Level Conference on CPEC and Beyond: How China Enabled Pakistan’s Energy Transition.

- Policy Dialogue on the Development of SEZs under CPEC: Learnings from China’s Green Model.

These interactions focused on the current state of SEZ governance, their gender implications, the localization of green technologies, and the regulatory frameworks shaping women’s inclusion in Pakistan’s industrial future. Insights from these engagements informed the analysis of institutional bottlenecks and recommendations proposed in this paper. The study’s methodological framework is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodological approach for the study.

3. Key Findings and Discussion

3.1. Gender-Blind Industrialization and Legal Ambiguity in SEZ Governance

Pakistan’s SEZ development is advancing under the SEZ Act (2012), which mandates compliance with domestic labor laws, but it does not clarify the nature and scope of the laws which apply to different SEZ models [1]. Export Processing Zones are explicitly exempt from key labor protections, including minimum wage guarantees, social security, and occupational safety. This creates a legal vacuum that disproportionately affects women, who are significantly overrepresented in temporary or precarious jobs; recent study found a persistent gender gap in permanent contracts [5]. These legal and regulatory gaps intersect with gender-specific vulnerabilities. Safety protocols are rarely designed with women in mind; standard Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is often ill-fitting for women and night-shift assignments expose women to heightened risks of harassment and violence, particularly during commutes or when working in isolation [6,7].

Moreover, Pakistan’s broader labor rights regime remains inadequate for ensuring gender equity in industrial zones. Pakistan lacks an enforceable Equal Pay Act. Women currently earn between Rs 700 to Rs 750 for every Rs 1,000 earned by men, reflecting a pay gap of 25 to 30 percent [8]. Pakistan also does not have any specific law prohibiting discrimination on the grounds of pregnancy, marital status, or family responsibilities. Employer liability schemes for maternity benefits incentivize exclusionary hiring practices, where women of childbearing age are often bypassed or dismissed upon marriage or pregnancy [9]. Even after the 2022 amendments to the Protection Against Harassment of Women at the Workplace Act, enforcement remains uneven [10], especially for women in informal or precarious employment, who face systemic vulnerabilities due to weak grievance mechanisms, lack of safe transport, and inadequate childcare infrastructure.

Compounding these governance deficiencies is the broader absence of gender-disaggregated labor market data across Pakistan. This national-level data gap extends into SEZs; without reliable data on employment patterns, wages, skills, and leadership representation, policymakers cannot track progress, identify exclusionary trends, or design effective interventions. This data gap is particularly concerning given Pakistan’s stated ambitions to position CPEC 2.0 as a driver of green and high-tech manufacturing, including solar photovoltaics, electric vehicles, and electronics assembly. Global experience shows that unless addressed early, high-tech industrialization often reproduces male-dominated labor hierarchies, leaving women concentrated in low-skill, peripheral roles.

Evidence from Pakistan’s own SEZ development highlights the risks of moving forward without corrective action. A recent empirical study of the Allama Iqbal Special Economic Zone in Faisalabad reveals how SEZs can generate structural social vulnerabilities when governance frameworks are underdeveloped [11]. Although land compensation initially raised household consumption, the lack of structured employment pathways and social protections triggered structural vulnerabilities including unproductive spending, labor market precarity, and social risks such as dowry inflation and early marriages.

These findings confirm that SEZs will not automatically translate into inclusive development and may in fact produce adverse social outcomes if left unchecked. The absence of social safeguards, labor protection and gender-responsive governance mechanisms, such as upskilling quotas, hiring targets, and workplace safety standards, in SEZs means that even in formal employment, gender-based exploitation, wage theft, and unsafe working conditions remain prevalent.

3.2. Global Patterns of Gendered Discrimination in SEZ Employment

Globally, SEZs have long relied on feminized labor, with women comprising 60–80% of the SEZ workforce on average, and up to 90% in some countries [12]. Yet this inclusion has often been structurally exploitative rather than empowering. Women, when hired, are typically concentrated in low-skill, low-value assembly work, often justified through stereotypes of docility, and low wage expectations [13]. These assumptions perpetuate occupational segregation, wage suppression, and restricted mobility. SEZs have also been linked to poor wage compliance, denial of maternity rights, forced resignations and discriminatory hiring practices against married women and women with children [14]. Evidence from SEZs around the world underscores these dynamics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparative Impacts of SEZ Development on Women’s Autonomy.

Beyond exploitation, the initial gains from feminization of labor have proven structurally unsustainable as women’s employment is based on their disadvantages in the labor market. Women’s participation in SEZs is often temporary, insecure, and structurally vulnerable to defeminization, a decline in the share of female workers as industries upgrade. There is clear evidence of defeminization in export labor as industrial structures are upgraded to higher value-added, capital and technology intensive, or skill-based sectors or, in some cases, where the gender wage gap has narrowed [14]. This trend is reinforced by both structural and institutional factors The drivers of defeminization are both structural and institutional. Women’s socialization into feminine vocational streams systematically restricts their entry into higher-wage, innovation-linked sectors, reserved for men. Technical roles are gender-typed as ‘masculine,’ excluding women from promotion pathways in upgraded sectors. Women are also less likely to receive on-the-job training and retraining due to employer biases which perceive women as unreliable due to anticipated domestic responsibilities [14,21]. The unpaid care economy further limits women’s ability to engage in training. Globally, women perform over 70% of caregiving hours and 75% of all unpaid care work. In Pakistan, women shoulder the majority of household and family care, leaving them with little time or energy for skilling initiatives [22].

These dynamics are well documented across regions. In Mexico’s maquiladoras, the female share of operatives fell from 77% to 41% as production became more technologically intensive, despite overall employment growth [23]. In Korea’s Masan SEZ, the female share dropped from 85% to 62% due to a combination of industrial upgrading and wage pressures following female-led labor resistance [24]. Similarly, a cross-national analysis found that a 1 percent increase in capital intensity leads to a 0.244 percent decrease in women’s share of employment, confirming a significant negative relationship. [25]. Studies show jobs dominated by women (e.g., clerical, low-skill assembly) are more vulnerable to automation than male-dominated occupations. A recent UN report found that 9.6% of “female” jobs are likely to be transformed by AI, compared to only 3.5% of “male” jobs [26].

Pakistan’s SEZs under CPEC 2.0 risk replicating these patterns. The expansion of high-tech sectors such as solar PV, EV manufacturing, and advanced electronics, if undertaken without gender-responsive safeguards, may displace women from even the limited roles they currently occupy. A study from Gujarat found that while the absolute number of female SEZ workers increased from 2010 to 2020, their proportional share declined due to casualization and socio-cultural barriers [27]. These trends show how gender-neutral SEZ models can reinforce, rather than redress, gendered inequalities unless proactively corrected.

3.3. Women in Green Industrialization: A Missed Opportunity?

CPEC’s first phase was defined by energy cooperation, with China emerging as Pakistan’s largest energy investor. As CPEC 2.0 shifts focus toward industrial development and technology transfer through SEZs, green industrialization is gaining strategic relevance, both due to domestic imperatives and China’s broader investment transition [28]. In 2024, renewable energy accounted for nearly 30% of all energy-related BRI activity, a 60% increase over the previous year and the highest share on record [29]. As a key BRI partner, Pakistan is likely to follow this shift. SEZs under CPEC will be central to enabling this transition, especially as Dhabeji SEZ in Sindh attracted direct interest from Chinese solar firms to set up manufacturing units for solar panels, inverters, and batteries [30]. But unless their design and governance proactively address structural gender inequalities, these SEZs may reinforce, rather than rectify, existing disparities.

Energy is one of the least gender-diverse sectors globally. Women make up only 20% of the global energy workforce, despite accounting for 40% of overall employment. They face a gender pay gap of nearly 15% at equivalent skill levels, and are starkly underrepresented in decision-making; women hold less than 15% of senior management roles and only 11% of startup founder positions in the energy sector [31].

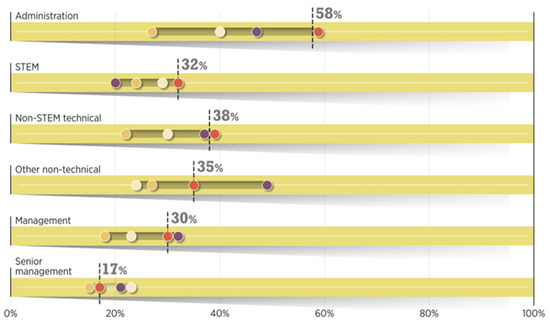

Renewables, however, offer a relatively better landscape. Women represent 32% of the workforce in renewables, higher than the 22% in fossil fuels, and approximately 40% in the solar PV industry [32]. This makes solar one of the most gender-inclusive subsectors in energy by overall participation. Yet this headline figure obscures deeper structural exclusions. Women are concentrated in administrative and finance functions, and significantly underrepresented in engineering, operations, and technical management roles [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Women in the solar PV workforce, by activity and region [32].

The trend is echoed in national contexts. In Brazil’s solar sector, for example, women made up 41% of the workforce in 2023. Yet this concentration was highest in administrative, finance and human resource roles, at 53%, compared with 24% in commercial activities. Women held only 7% share in marketing, management and project engineering in and just 2% in assembly and installation. One third of PV integrators reported having no female employees at all [33]. Therefore, even in the most inclusive energy subsector, systemic exclusion persists.

Without deliberate, enforceable gender mechanisms, Pakistan’s green industrialization under SEZs risks reproducing these global trends. This trajectory, however, is not inevitable. Evidence from Ghana challenges the view that SEZs are inherently disempowering for women. A study of 328 firms found that women-led SEZ firms outperformed non-SEZ counterparts in both product and process innovation, driven by inclusive firm policies, access to mentoring, and strong compliance systems [34]. Zambia’s Skills Development for Renewable Energy (SkiDRES) project also offers valuable lessons; by conducting gender-sensitive skills assessments and offering demand driven training, it successfully increased women engineers’ participation in training courses [33]. More broadly, evidence shows that women’s autonomy in SEZs is deeply shaped by institutional design. When gender is mainstreamed in firm strategy and policy, from hiring to promotion and infrastructure provision, SEZs can serve as effective platforms for gender-equitable industrial upgrading. Table 2 provides a lifecycle-based framework of SEZ development stages, matched with gender-specific risks and policy interventions.

Table 2.

Operationalizing a Gender-Responsive SEZ Lifecycle.

Other programs offer institutional models. Bangladesh’s BEPZA Labor Program led to protection of wage rights and fewer worker grievances. Cambodia’s Better Factories program and Lesotho’s sourcing codes linked buyer accountability to gendered workplace outcomes [12]. Though often donor-backed, these interventions underscore that gender-equitable SEZs are not only possible but necessary for inclusive industrial growth.

4. Conclusions and the Way Forward

Pakistan’s SEZ policy under CPEC 2.0 must evolve from narrow metrics of investment and exports to a broader commitment to equitable industrial transformation. Global and regional experience underscores that industrial upgrading does not automatically translate into gender-equitable outcomes; instead, if pursued without gender safeguards, it often displaces women from even the limited roles they initially occupy. Pakistan risks reproducing this pattern unless gender equity is embedded from the outset, before value chains solidify and institutional hierarchies are entrenched.

SEZs, by design, offer centralized governance frameworks and limited geographies, making them ideal platforms for piloting gender-responsive reforms for gender-responsive industrial reform. Pakistan should institutionalize ZSR as an operational framework across all CPEC SEZs [35]. This includes safeguarding informal livelihoods during land acquisition, ensuring direct access to both factory and service-sector jobs for women, and providing targeted skilling in supervisory, managerial, and entrepreneurial roles. Promotion and retention pathways must be structured to ensure gender parity across the industrial hierarchy.

Pakistan’s National Gender Policy Framework (2022) provides a roadmap for integrating gender perspectives into economic and institutional planning, including mandates for gender-responsive budgeting, institutional capacity building, and sex-disaggregated data systems [36]. Aligning SEZ policies with this framework, mandating gender equity plans and reforming the SEZ Act to clarify the applicability of national labor laws can accelerate gender inclusion in industrial zones. Anti-discrimination audits and third-party monitoring, sex-disaggregated targets, responsible actors and enforceable, workplace safety standards, and indicators to measure progress and outcomes must be linked to zone licensing and incorporated into SEZ planning and budgeting to retain and empower women workers. Importantly, these downstream reforms must be matched by upstream interventions. Gendered occupational segregation is rooted in broader educational and social norms. Without reforms in vocational training, STEM education, and elimination of gender biases in admission policies, curriculum design, and instruction, women will remain excluded from the very sectors driving Pakistan’s green industrial transition. The goal is not just participation, but upward mobility and structural transformation of the gendered labor regime.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N. and S.S.; methodology, A.N. and U.U.R.Z.; formal analysis, A.N. and S.S.; data curation, analysis and discussion, A.N. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shahid, Z.; Hameed, S.; Faruqi, S. Special Economic Zones in Pakistan Undermine Women’s Human Rights. OpenGlobalRights, 27 October 2020. Available online: https://www.openglobalrights.org/special-economic-zones-in-pakistan-undermine-womens-human-rights (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). Training on Gender and Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial Development. 2021. Available online: https://www.unido.org/gender-and-isid-training#:~:text=Industrialization%20directly%20affects%20women%E2%80%99s%20roles,if%20properly%20designed%20and%20implemented (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Fostering Women’s Economic Empowerment Through Special Economic Zones: The Case of Bangladesh. World Bank. 2011. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/653131468006880220/pdf/727030WP0Box370and0women0bangladesh.pdf#:~:text=Economic%20Zones%E2%80%9D%E2%80%94summarizes%20their%20findings,to%20opportunities%20for%20professional%20advancement (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Yu, Y.; Shieh, S. Why Gender Should Matter in the Belt and Road Initiative. Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, 8 December 2022. Available online: https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/blog/why-gender-should-matter-in-the-belt-and-road-initiative/#:~:text=sensitivity%20to%20gender%20impacts,such%20policy%20for%20the%20BRI%E2%80%99 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Brilli, Y.; Fanfani, B.; Piazzalunga, D. The Gender Gap in Employment Protection: The Role of Fertility and Statistical Discrimination. World Bank, 21 March 2025. Available online: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/9fe224595c1ecfe9e508d7f3be205a8d-0080012025/related/D2-3-P-Temporary-contracts-Fertility-1.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Personal Protective Equipment Is Sexist. 9 March 2021. Available online: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2021/03/09/personal-protective-equipment-is-sexist/#:~:text=obligation%20to%20put%20the%20needs,to%20fit%20HCWs%20of%20some (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Moore, S.; Ballardie, R. The Health and Safety Impacts of Night Working. Trades Union Congress (TUC), 24 October 2024. Available online: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/health-and-safety-impacts-night-working#:~:text=match%20at%20L1692%20and%20the,work%2C%20in%20particular%2C%20on%20fatigue (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Ahmed, A. Women in Pakistan Earn Significantly Less than Men: ILO. Dawn, 17 July 2025. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1924668#:~:text=The%20’Pakistan%20Gender%20Pay%20Gap,also%20significant%20by%20international%20standards (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Ahmad, I. Maternity Protection in Pakistan. The News International, 8 February 2020. Available online: https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/610420-maternity-protection-in-pakistan (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Iqbal, S. Evolution of Workplace Harassment Laws in Pakistan: The Protection Against Harassment of Women at the Workplace Act 2010 and the 2022 Amendment. International Bar Association, 12 December 2023. Available online: https://www.ibanet.org/Evolution-of-workplace-harassment-laws-in-Pakistan (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Karim, S.; Xiang, K.; Hameed, A. Impact of Special Economic Zones on Socioeconomics and Local Development in Pakistan: Evidence from Allama Iqbal Special Economic Zone, Faisalabad. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fostering Women’s Economic Empowerment through Special Economic Zones: Comparative Analysis of Eight Countries and Implications for Governments, Zone Authorities and Businesses. World Bank. 2011. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/657561468148771219/pdf/727040WP0Box370sez0and0women0global.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Elson, D.; Pearson, R. ‘Nimble Fingers Make Cheap Workers’: An Analysis of Women’s Employment in Third World Export Manufacturing. Fem. Rev. 1982, 7, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejani, S. The Gender Dimension of Special Economic Zones. In Special Economic Zones: Progress, Emerging Challenges, and Future Directions; Farole, T., Akinci, G., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goodburn, C.; Knoerich, J.; Mishra, S.; Calabrese, L. Zones of Contention: Performance, Pitfalls and Politics of China-Associated Economic Development Zones in Africa. Lau China Institute, King’s College London. 2024. Available online: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/lci/assets/2024/zones-of-contention.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Glick, P.; Roubaud, F. Export Processing Zone Expansion in Madagascar: What Are the Labour Market and Gender Impacts? J. Afr. Econ. 2006, 15, 722–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregnancy-Based Sex Discrimination in the Dominican Republic’s Free Trade Zones: Implications for the U.S.-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA). Human Rights Watch, April 2004. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/legacy/backgrounder/wrd/cafta_dr0404.htm#:~:text=Women%20seeking%20employment%20in%20the,submit%20to%20mandatory%20pregnancy%20testing (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU). Behind the Brand Names Working Conditions and Labour Rights in Export Processing Zones. 2004. Available online: https://biblioteca.cejamericas.org/bitstream/handle/2015/4882/Behind_the_brand_names.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Pun, N. Women Workers and Precarious Employment in Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, China. Gend. Dev. 2004, 12, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Pun, N. The Dormitory Labour Regime in China as a Site for Control and Resistance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 17, 1456–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, D. ‘More and More Technology, Women Have to Go Home’: Changing Skill Demands in Manufacturing and Caribbean Women’s Access to Training. Gend. Dev. 2001, 9, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.B.; Ramanarayanan, D. Global Health & Gender Policy Brief: The Global Care Economy. Wilson Center, 21 April 2022. Available online: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/global-health-gender-policy-brief-global-care-economy#:~:text=work%2C%20which%20is%20unpaid%2C%20underpaid%2C,to%20greater%20gender%20inequities%20worldwide (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Fussell, E. Making Labor Flexible: The Recomposition of Tijuana’s Maquiladora Female Labor Force. Fem. Econ. 2000, 6, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, M.; Yokota, N. Revisiting Labour and Gender Issues in Export Processing Zones: The Cases of South Korea, Bangladesh and India. October 2008. Available online: https://ir.ide.go.jp/record/37993/files/IDP000174_001.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Caraway, T. From Cheap Labor and Export-Oriented Industrialization to the Gendered Political Economy Approach. In Assembling Women: The Feminization of Global Manufacturing; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Le Poidevin, O. AI Poses a Bigger Threat to Women’s Work, than Men’s, Says Report. Reuters, 20 May 2025. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/world-at-work/ai-poses-bigger-threat-womens-work-than-mens-says-report-2025-05-20/#:~:text=It%20found%209.6,jobs%2C%20such%20as%20secretarial%20work (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Thapa, P.M.; Chudasama, K.M. Gender dimension of employment in special Economic Zones: A Study of Gujarat State. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2022, 7, 1587–1588. [Google Scholar]

- Isaad, H.; Sayed, M.H. Pakistan Must Rebuild Chinese Investor Confidence in Its Energy Transition. IEEFA, 5 March 2025. Available online: https://ieefa.org/resources/pakistan-must-rebuild-chinese-investor-confidence-its-energy-transition (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Nedopil, C. China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2024. February 2025. Available online: https://greenfdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Nedopil-2025_China-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-BRI-Investment-Report-2024-1.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- China Eyes $1B Medical City in Dhabeji SEZ. The Daily CPEC, 12 December 2024. Available online: https://thedailycpec.com/china-eyes-1b-medical-city-in-dhabeji-sez/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Understanding Gender Gaps in the Energy Sector. International Energy Agency (IEA). Available online: https://www.iea.org/spotlights/understanding-gender-gaps-in-the-energy-sector (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Solar PV: A Gender Perspective. 2022. Available online: https://www.pseau.org/outils/ouvrages/irena_solar_pv_a_gender_perspective_2022.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA); International Labour Organization (ILO). Renewable Energy and Jobs: Annual Review 2024. IRENA and ILO, 2024. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/2024-10/IRENA-ILO%20Renewable%20energy%20and%20jobs_2024.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Ackah, C.G.; Osei, R.D.; Kusi, B.A. Special Economic Zones, Gender and Innovations: New Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2342487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zone Social Responsibility Toolbox. King’s College London. Available online: https://zsrtoolbox.org/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Ministry of Planning, Development and Special Initiatives. National Gender Policy Framework. Government of Pakistan. 2022. Available online: https://pc.gov.pk/uploads/report/NGPF.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).