Abstract

WAAM is a technique for fabricating large-scale metallic components in an efficient and cost-effective way. Inconel alloys are a nickel-based superalloy popular for their excellent mechanical properties and corrosion resistance. They have been widely investigated for fabricating components using WAAM. This review aims to fill the gap dedicated to the fabrication of WAAM-based Inconel alloy parts. The WAAM of Inconel alloys is then thoroughly reviewed in terms of microstructure and mechanical behavior, as well as the effect of relevant process variables, including heat input, travel speed, and shielding gas mixture. Furthermore, this article also highlights several challenges and defects that occurred during and after fabricating the component, providing valuable insights. Several strategies for improvement are presented to improve the performance of the WAAM of Inconel alloys.

1. Introduction

WAAM is a special type of metal AM technique. It provides substantially improved deposition rates, economic feasibility, and the potential to produce large-sized parts [1,2]. Among other alloys that were tested with WAAM, Inconel 625 and Inconel 718, which are nickel-based superalloys, have drawn much attention owing to their superior mechanical strength and stability at high temperatures [3]. Inconel alloys are utilized in the aerospace, chemical, marine, and nuclear industries due to their ability to perform well in hostile environments [4]. Traditional methods of fabrication, such as casting and forging, are not viable due to high material wastage, significant production time, and high processing costs [5]. WAAM of Inconel alloys provides a reliable choice as it allows for cost-effective material use and freedom of designing while ensuring exceptional mechanical and microstructural properties [1].

Despite its benefits, WAAM-fabricated parts of Inconel alloys face several challenges, including microstructural inhomogeneity, residual stresses, pores, and phase segregation [6]. The variables of the WAAM process—heat input, wire feeding rate, torch travel speed, and shielding gas—have a significant influence on the final material properties [7]. In addition, machining is sometimes required to enhance mechanical performance and structural integrity [1]. This paper provides a review of the WAAM of Inconel alloys, focusing on their microstructure and mechanical properties. This work examined the effect of various process variables, challenges, and strategies during WAAM-based fabrication on Inconel alloys. By synthesizing findings from earlier literature, this review provides insights into the current state of WAAM for Inconel alloys and highlights potential research directions to further enhance the technology for ready use in industries.

2. WAAM Variants Used with Inconel Alloys

2.1. Cold Metal Transfer Welding-Based WAAM

Cold Metal Transfer (CMT) WAAM has become a productive way of producing Inconel parts. It has merits such as high deposition rates, less heat input, and better microstructural integrity [8]. CMT-WAAM relies on precise control of the torch and short-circuit metal transfer, which promotes a stable arc and minimizes spattering. This results in spatter-free deposition with excellent mechanical and corrosion-resistant properties [9]. One of the major merits of CMT-WAAM is that it controls heat input, resulting in a fine microstructure and improved mechanical performance. Mookara et al. [10] fabricated WAAM parts of Inconel 625. They reported that the deposition achieved by combining steady dip short-circuiting of metal is the best choice to develop defect-free builds with desirable microstructural characteristics [2]. They compare samples developed through a standard CMT continuous and discontinuous WAAM of Inconel 625 alloy. They concluded that discontinuous CMT is suitable for fine, detailed components.

Microstructural analysis of CMT-WAAM-fabricated Inconel 625 exhibited a homogeneous dendritic microstructure with finer intermetallic phases. The low heat input in CMT-WAAM reduced the presence of harmful Laves phases, which are well-documented to have a detrimental effect on mechanical properties, such as tensile strength and ductility [8]. Additionally, the study using electrochemical corrosion validation confirmed that CMT-WAAM deposited specimens exhibit higher corrosion resistance compared to conventionally produced Inconel 625, due to the improved microstructure and homogeneous phase distribution [1]. For Inconel 718, CMT-WAAM yielded a UTS of 1110 MPa and a yield strength (YS) of 858 MPa in the heat-treated form, which is significantly better than the as-deposited condition [11]. Refinement of cellular-dendritic microstructures, achieved through reduced heat input, contributed to strengthening the mechanical properties, in addition to enhancing corrosion resistance.

Mechanical testing results of CMT-WAAM of Inconel 625 reported YS to vary between 369 MPa and 417 MPa, UTS from 630 MPa to 773 MPa, and elongation from 49.6% to 59.2% at ambient temperature (20 °C) [2]. For Inconel 718, the YS decreased by 27–30%, and the UTS dropped by 25–31% with thermal exposure at higher temperatures of 650 °C, indicating the impact of thermal exposure on mechanical strength [12]. CMT-WAAM of Inconel 825 produced a UTS between 505 MPa and 514 MPa and a YS between 199 MPa and 207 MPa [13]. The major benefit of employing CMT compared to traditional MIG-WAAM is the significant reduction in dilution effects, resulting in a more uniform microstructure with enhanced mechanical properties. CMT-WAAM also resulted in a finer grain structure, which enhanced fatigue life and wear resistance.

2.2. Tungsten Inert Gas Welding-Based WAAM

GTAW is widely utilized in WAAM due to its precise heat control and superior weld quality. The GTAW-WAAM process offers advantages such as minimal spatter, controlled heat input, and improved mechanical properties when optimized [3]. Despite its slower deposition rate compared to GMAW-based WAAM, GTAW is preferred for applications requiring high structural integrity and minimal defects [12].

GTAW-WAAM of Inconel 625 showed a fine-grained dendritic structure. It also highlighted uniform phase distribution [5]. Their study concluded that adjusting the travelling rate and feeding rate of wire significantly affects the formation of interdendritic Laves phases. These phases deteriorate hardness and tensile strength. Furthermore, the implementation of hot-wire GTAW showed significant deposition efficiency and reduced pores in WAAM-fabricated Inconel 625 components [14]. The tensile properties of GTAW-WAAM Inconel 625 indicated YS as similar to conventionally manufactured parts, making it a good choice for marine and high-temperature applications. Hardness measurements revealed that post-processing heat treatment can significantly enhance wear resistance and overall component performance [10]. The corrosion resistance of the GTAW-WAAM deposited wall part was found to be improved due to the reduced heat input, thereby reducing oxidation-related defects [9]. At 20 °C, GTAW-WAAM Inconel 625 has YS of 414 MPa–758 MPa, UTS of 827 MPa–1103 MPa, and elongation percentage of 30–60% [12].

Inconel 718 components manufactured using TIG-WAAM exhibit tensile strengths comparable to those manufactured using traditional methods, and with better grain refinement and solidification cracking resistance [15]. One of the most significant advantages of TIG-WAAM in Inconel 718 is the reduced formation of unwanted phases, such as Laves phases, which are typically observed in high-energy input processes, like MIG-WAAM. The finer equiaxed microstructure leads to improved fatigue life and creep resistance. TIG-WAAM is thus appropriate for aerospace and gas turbine applications where high performance is needed. Low dilution rates of TIG-WAAM also lead to improved chemical homogeneity between deposited layers, resulting in uniform mechanical properties throughout the component.

2.3. Metal Inert Gas Welding-Based WAAM

GMAW is a common welding technique for Inconel alloys using the WAAM process. MIG-WAAM is used for high-deposition-rate components due to its effective material deposition and high energy density [10]. MIG-WAAM provides a quicker build time than GTAW-WAAM, but it requires stringent process control to prevent defects such as porosity and cracking [12].

MIG-WAAM of Inconel 625 components revealed that the process results in a coarser dendritic microstructure with greater interdendritic Laves phase development, impacting mechanical performance [10]. Welding parameter optimization, such as travel speed, wire feed rate, and shielding gas composition, can reduce these effects and improve deposit quality [8]. Research has proven that the MIG-WAAM heat input is slightly higher than that of CMT-WAAM, resulting in more residual stresses. Interpass cooling techniques and stress-relief heat treatment are recommended to reduce this, ensuring improved fatigue life and reduced defects [14]. The pulsed arc transfer hybrid MIG-based WAAM process has been shown to enhance microstructure refinement and mechanical properties [5]. The mechanical properties of parts produced using MIG-WAAM exhibited high tensile strength and hardness, with minimal variability in ductility, compared to GTAW-based WAAM deposits [16]. The rapid cooling rate characteristic of MIG-WAAM causes residual stress accumulation, which needs post-deposition stress relief treatments to enhance the reliability of components [1]. The summary comparision of WAAM variants is presented in Table 1.

Their findings revealed that the excellent deposition efficiency and mechanical homogeneity of MIG-WAAM facilitate part manufacturing at a large scale [9]. In the case of Inconel 718, the MIG-WAAM components exhibited a UTS ranging between 760 MPa and 766 MPa and a YS between 440 MPa and 482 MPa, with an elongation of 39% to 45.6% [17].

Table 1.

Summary of comparison of WAAM variants.

Table 1.

Summary of comparison of WAAM variants.

| Parameter | MIG-WAAM | TIG-WAAM | CMT-WAAM | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat input | High | Moderate | Low | [8] |

| Deposition Rate (kg/h) | High (4–6) | Low (1–2) | Moderate (2–4) | [18] |

| Residual stress | High due to rapid solidification | Moderate | Low due to reduced heat input | [5] |

| Surface finish | Rough due to spatter and high heat input | Smooth, minimal defects | Very smooth, minimal spatter | [19] |

| Cracking susceptibility | High (solidification cracking) | Moderate (controlled cooling) | Low (reduced thermal gradients) | [16] |

| Best application areas | Large-scale structural components, marine and energy industries | Aerospace and high-precision applications | Corrosion-resistant applications, thin-walled structures | [2,20] |

3. Challenges with WAAM of Inconel Alloys

Although WAAM has made great strides toward producing Inconel alloy components, a series of intrinsic limitations restricts its bulk industrial use. Microstructural inhomogeneity is one of the fundamental issues resulting from the repetition of thermal cycling in the build process. Rapid heating and cooling produce an inhomogeneous microstructure with the tendency to form brittle Laves phases, which degrade the mechanical properties [10]. The enhanced segregation of Nb and Mo in the interdendritic regions is responsible for localized embrittlement, as it lowers ductility and impact strength [3]. Although optimized heat treatment and controlled processing parameters to some degree minimize Laves phase formation, the complete avoidance of these detrimental phases is elusive [20].

Residual stress accumulation is another major disadvantage of WAAM. Layer-by-layer deposition introduces non-uniform expansion and shrinkage, leading to the development of high tensile residual stresses that are prone to cause warping and part distortion [4]. The process is most prevalent in large-area builds, and high-stress gradients develop in the part. Stress relief processes, such as interpass cold rolling, heat treatment, or peening, have, in some cases, been employed to mitigate internal stress, although the success is dependent on the deposition strategy and part geometry [5]. Unrelieved residual stresses also increase the material’s propensity to form crack propagation, primarily through solidification and liquation cracks [2]. The impact on structural integrity resulting from such cracks is appreciable; hence, WAAM-manufactured Inconel 625 parts are less reliable for use in safety-critical applications.

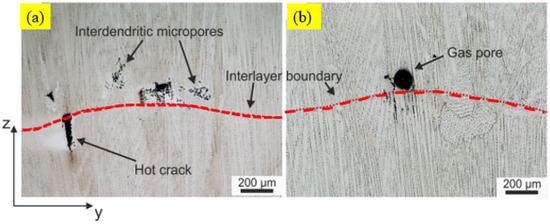

Porosity is another long-term problem with Inconel 625 fabricated with WAAM. The process itself is impacted by gas entrapment, lack of fusion defects, and keyhole instability, all of which are sources of voids in the deposit [9]. The defects, including hot cracks and micropores, are illustrated in Figure 1. Porosity reduces overall mechanical performance, notably fatigue resistance, which is a key concern for aerospace and marine applications. While advanced process control techniques, such as CMT and shielding gas composition optimization, have been designed, achieving a defect-free build remains beyond reach [21].

Figure 1.

(a) The micropores, hot crack, (b) gas porosity in WAAM of IN718 [22].

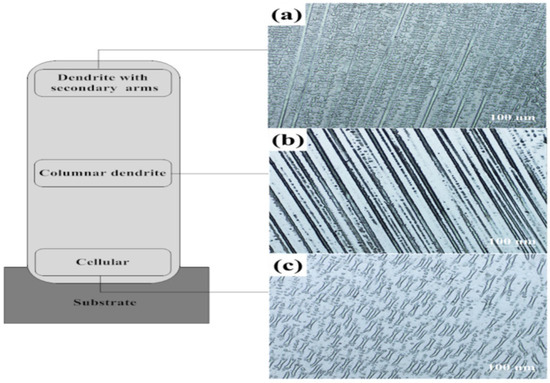

Additionally, oxidation-based defects also contribute to the integrity of the WAAM part. High-temperature processing within an uncontrolled environment resulted in the formation of surface oxides, which negatively impact corrosion resistance [1]. Shielding gas composition and post-processing treatments, such as surface machining and peening, must be used to restore surface quality; however, these are expensive and add complexity to the overall process [20]. Another critical limitation of WAAM is the anisotropy of the mechanical properties of the manufactured components. The directional solidification layer-by-layer build-up creates a large property [12]. Figure 2 presents anisotropy in IN625 [23]. Components exhibit superior strength in the transverse direction but are marred with inferior ductility and toughness along the direction of build as a result of columnar grain structures [3]. Mechanical performance inhomogeneity makes it challenging to apply WAAM components to load-carrying structures without extensive post-processing, such as heat treatment or mechanical working, to enhance the structure’s homogeneity [14]. Even with such post-processing methods, it is challenging to achieve isotropic properties comparable to those of wrought Inconel 625, thereby limiting the full potential of WAAM for high-priority engineering applications.

Figure 2.

The longitudinal section microscopic appearances of the top, middle, and bottom different parts (a) dendrite with secondary arms, (b)columnar dendrite, (c) celular [23].

Despite such limitations, current research continues to look for ways to enhance the microstructural homogeneity and reliability of WAAM-fabricated Inconel 625. Emerging process monitoring, strategic deposition planning, and hybrid processes combining WAAM with conventional fabrication processes are being looked into to transcend such limitations [7]. Still, significant effort is yet to be directed toward bridging the gap between conventionally manufactured parts and WAAM-fabricated parts in terms of microstructural homogeneity, mechanical response, and longevity. Such limitations need to be overcome in order to transition WAAM from an experimental process to an advanced industrial production process for high-temperature nickel alloys.

4. Strategies to Improve Properties of WAAM of Inconel Alloys

4.1. Interpass Cold Rolling

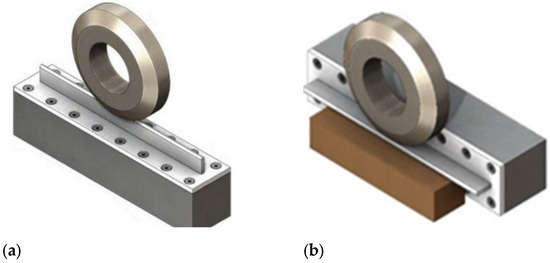

Interpass cold rolling is an effective technique applied between successive layers during WAAM to improve the microstructure and, consequently, the mechanical behavior of Inconel 625. Cold rolling refines the coarse columnar dendritic grains formed during WAAM by introducing plastic deformation, promoting recrystallization, and transforming them into finer equiaxed grains. This refinement mitigates anisotropic behavior and enhances the isotropic properties of WAAM-fabricated components. Zhang et al. [24] investigated the effect of several rolling forces (50 kN and 75 kN) on WAAM Inconel 718, which responds similarly to Inconel 625 under cold rolling, as shown in Figure 3a,b. Their study demonstrated that the coarse columnar dendritic structure with a mean dendrite arm spacing of 85 µm in the as-deposited condition was refined into equiaxed grains of 26.5 µm and 14.7 µm for rolling forces of 50 kN and 75 kN, respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic of vertical rolling of WAAM part; (b) side rolling of WAAM part [25].

This microstructural refinement led to a substantial improvement in mechanical properties. The UTS increased from 840.7 MPa in the as-deposited condition to 1357.3 MPa after 75 kN cold rolling, with a corresponding increase in YS from 472.5 MPa to 1067.4 MPa, while maintaining a reasonable elongation of 15.8%. Moreover, at elevated temperatures (650 °C), the UTS and YS of the 75 kN rolled sample increased to 1137 MPa and 1009.1 MPa, respectively, with an elongation of 11.48%, approaching that of the wrought material (12% elongation).

4.2. Interpass Cooling

Interpass cooling is employed during the WAAM process, utilizing active cooling of the deposited passes. Interpass cooling minimizes the accumulation of heat. Zhang et al. [24] investigated the effect of interpass layer temperatures on Inconel 625 fabricated with WAAM. The findings established that lower interpass temperatures created finer grain microstructures and better mechanical properties in the form of higher UTS and microhardness. Specifically, a reduction in interpass temperature from 300 °C to 100 °C enhanced the UTS by 7.3% and microhardness by 11.5%. Yangfan et al. [23] investigated the effect of heating input on Inconel 625 alloy produced using WAAM and revealed that interpass temperatures achieved with cooling under active conditions resulted in finer microstructures and good mechanical properties.

For Inconel 718, a study by Karmuhilan and Kamanan [26] investigated the effect of applying an interpass temperature of 100 °C versus deposition without interpass cooling. Their study revealed that both cooling strategies produced a microstructure dominated by columnar dendrites, extending along the height of the deposited component, indicating that interpass cooling did not significantly alter the overall microstructure. However, components deposited without interpass cooling exhibited superior mechanical properties, with an 8.5% higher UTS and an up to 19.2% higher YS compared to those fabricated with interpass cooling.

4.3. Heat Treatment

It is a very important process for the modification of the microstructure and improving the mechanical properties of WAAM-manufactured Inconel 625. A large number of studies have focused on heat treatment processing to develop higher-performance operations. Tanvir et al. [7] also conducted an experiment on the impact of different heat treatment processes on Inconel 625 fabricated using WAAM, establishing that adequate heat treatment would dissolve secondary phases and precipitates, thereby enhancing the mechanical properties. They illustrated from their study that dendritic segregation is reduced in post-heat-treated samples, ensuring microstructural homogenization with improved strength and ductility. Maronek et al. [27] carried out comparative studies of the effects of heat treatment on WAAM-fabricated Inconel 625 and noted that stress relief at 1066 °C for 1.5 h, HIP at 1163 °C for 3 to 4 h, and solution annealing at 1177 °C for 1 h led to microstructural homogenization and grain refinement and converted coarse columnar dendrites into equiaxed grains. Their results demonstrated that post-heat-treated WAAM samples were softer and exhibited better elongation, with tensile characteristics comparable to those of conventionally processed Inconel 625. Micro-indentation hardness of heat-treated WAAM samples dropped to the range of HV 186 to HV 220, whereas the as-built samples ranged from HV 191 to HV 304. Heat treatment also enhanced the YS, which varied from 285 MPa to 371 MPa, and elongation from 52% to 70% compared to the as-built state [28].

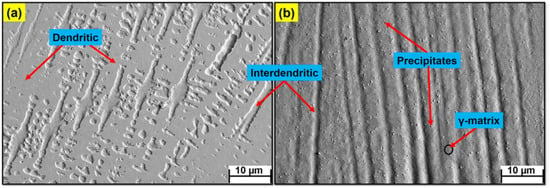

Sharma et al. [29] researched the significance of post-heat treatment on WAAM-CMT-produced Inconel 625 and illustrated that heat treatment for 2 h at 1100 °C and water quenching yielded the optimal blend of mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and grain refinement. They exhibited that this condition of heat treatment resulted in elevated tensile strength and impact toughness, while cyclic polarization tests agreed with the corrosion resistance as a result of optimized microstructure and reduced secondary phase formation. They also offered information on microstructure and hardness comparison between as-built and heat-treated WAAM-fabricated Inconel 625. According to their research, it was found that heat treatment above 1100 °C resulted in remarkable grain refinement and microstructural homogenization, leading to improved mechanical strength and reduced anisotropy in WAAM-fabricated components. These results highlight the need to optimize heat treatment parameters to obtain better performance in WAAM-fabricated Inconel 625 parts. The synergy of stress relief, HIP (Hot Isostatic Pressing), and solution annealing offers a promising solution to reduce anisotropy, refine grains, and enhance mechanical and corrosion properties. It can be seen from Figure 3a that the primary phases in the interdendritic region are Laves phases enriched with Nb, Mo, and MC carbides. As shown in Figure 3b, the existence of M6C carbides scattered at random is noted. Furthermore, certain precipitate phases, such as laves phases, are completely dissolved in the SA deposit. This leads to a higher amount of austenitic structure, as illustrated in Figure 4b.

Figure 4.

SEM of IN625 alloy: (a) as-deposited; (b) solution annealed [19].

4.4. Peening Process

It is the method to improve mechanical performance. It is a cold working technique in mechanical conditioning, in which tensile stresses are reduced by compressive pressure applied at the treatment surface. The process involves compressive stress at the component surface at a specific depth. For carbon steels, this depth is approximately 1 mm–2 mm. This technique is a good choice for small components deposited by WAAM, but it has a negligible effect on large, deposited materials [30].

5. Conclusions

With its high deposition rates, cost-effectiveness, and design flexibility, Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) has shown great promise for producing Inconel alloy components. However, obstacles like mechanical anisotropy, porosity, residual stresses, and microstructural inhomogeneity prevent it from being widely used in industry. Process variables have a significant impact on the performance of Inconel parts made using WAAM, so exact control is required to obtain the best possible material qualities. Each of the WAAM variations—CMT, TIG, and MIG—has unique benefits and drawbacks. While TIG-WAAM ensures high accuracy and fewer defects, making it a suitable choice for aerospace and marine applications, CMT-WAAM produces fine microstructures and superior mechanical properties because of its low heat input. MIG-WAAM also offers higher deposition rates, but it needs precise control of the process to mitigate defects like cracking and porosity.

To address these challenges, advanced post-processing methods such as interpass cold rolling, controlled interpass cooling, heat treatment, and peening have been explored. These methodologies refine the grain structure, thereby reducing residual stresses and enhancing mechanical and corrosion resistance, which brings WAAM-fabricated components closer to their traditionally produced counterparts. Optimization of WAAM parameters, integration with hybrid manufacturing processes, and advancements in in situ monitoring and real-time control are required to benefit from the full advantages of WAAM for Inconel alloys. By overcoming existing limitations, WAAM can revolutionize high-performance manufacturing, enabling its broader application in aerospace, marine, and energy industries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.F. and K.W.; methodology, D.P.; validation, N.S., K.F. and K.W.; formal analysis, D.P.; investigation, K.F.; resources, K.W. and D.P.; data curation, D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.P. and K.F.; writing—review and editing, K.F. and K.W.; visualization, N.S.; supervision, K.F.; project administration, N.S. and D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Silva, W.F.; Junior, G.M.M.; Oliveira, H.; Pires, J.C.A.; Carneiro, J.R.G. Evaluation of the properties of Inconel® 625 preforms manufactured using WAAM technology. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Votruba, V.; Diviš, I.; Pilsová, L.; Zeman, P.; Beránek, L.; Horváth, J.; Smolík, J. Experimental investigation of CMT discontinuous wire arc additive manufacturing of Inconel 625. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 122, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheepu, M.; Lee, C.I.; Cho, S.M. Microstructural Characteristics of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing with Inconel 625 by Super-TIG Welding. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2020, 73, 1475–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X. Investigation on the microstructure and corrosion properties of Inconel 625 alloy fabricated by wire arc additive manufacturing. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 106568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, O. Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) of Inconel 625 Alloy and its Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2021, 8, 1517–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan Kumar, S.; Kannan, A.R.; Kumar, N.P.; Pramod, R.; Shanmugam, N.S.; Vishnu, A.S.; Channabasavanna, S.G. Microstructural Features and Mechanical Integrity of Wire Arc Additive Manufactured SS321/Inconel 625 Functionally Gradient Material. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 5692–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanvir, A.N.M.; Ahsan, R.U.; Seo, G.; Kim, J.-D.; Ji, C.; Bates, B.; Lee, Y.; Kim, D.B. Heat treatment effects on Inconel 625 components fabricated by wire + arc additively manufacturing (WAAM)—Part 2: Mechanical properties. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 110, 1709–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akselsen, O.M.; Bjørge, R.; Ånes, H.W.; Ren, X.; Nyhus, B. Microstructure and Properties of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing of Inconel 625. Metals 2022, 12, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junwen, J.; Zavdoveev, A.; Vedel, D.; Baudin, T.; Motrunich, S.; Klochkov, I.; Friederichs, S.; Strelenko, N.; Skoryk, M. CMT-based wire arc additive manufacturing of Inconel 625 alloy. Emerg. Mater. Res. 2023, 12, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mookara, R.K.; Seman, S.; Jayaganthan, R.; Amirthalingam, M. Influence of droplet transfer behaviour on the microstructure, mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of wire arc additively manufactured Inconel (IN) 625 components. Weld. World 2021, 65, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ding, J.; Ganguly, S.; Williams, S. Investigation of process factors affecting mechanical properties of INCONEL 718 superalloy in wire + arc additive manufacture process. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2019, 265, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhrish, Y.E.; Asad, M.; Khan, M.A.A.; Djavanroodi, F. Experimental investigations on wire arc additive manufacturing process using an Inconel 625 alloy wire. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 31, 8242–8253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, I.J.; Srinivas, J.; Leon, S.J.; Ramesh, A.; Rohith, I.J.; Senthil, T.S. Mechanical and microstructural investigation of multi-layered Inconel 825 wall fabricated using CMT-based WAAM. J. Alloys Metall. Syst. 2024, 8, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hu, Q.; Li, T.; Liu, W.; Tang, D.; Hu, Z.; Liu, K. Microstructure and Fracture Performance of Wire Arc Additively Manufactured Inconel 625 Alloy by Hot-Wire GTAW. Metals 2022, 12, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, C.E.; Coules, H.E.; Wu, G.; Khan, R.H.U.; Xu, X.; Williams, S. Wire + Arc Additively Manufactured Inconel 718: Effect of post-deposition heat treatments on microstructure and tensile properties. Mater. Des. 2019, 183, 108157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil, T.S.; Babu, S.R.; Puviyarasan, M. Mechanical, microstructural and fracture studies on inconel 825–SS316L functionally graded wall fabricated by wire arc additive manufacturing. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, S.; N, B. A Study on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Inconel 718 Superalloy Fabricated by Novel CMT-WAAM Process. Mater. Res. 2024, 27, e20230258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srijha, T.; Balaji, V.G.; Saravanakumar, K.; Sanjay, V.; Thatchuneswaran, K. Analysis of Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Inconel 625 Alloy by Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM). Arch. Metall. Mater. 2024, 69, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, G.; Murugan, N.; Arulmani, R. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Inconel-625 slab component fabricated by wire arc additive manufacturing. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 36, 1785–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangfan, W.; Xizhang, C.; Chuanchu, S. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Inconel 625 fabricated by wire-arc additive manufacturing. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 374, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintala, A.; Kumar, M.T.; Sathishkumar, M.; Arivazhagan, N.; Manikandan, M. Technology Development for Producing Inconel 625 in Aerospace Application Using Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing Process. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 5333–5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurić, I.; Garašić, I.; Bušić, M.; Kožuh, Z. Influence of Shielding Gas Composition on Structure and Mechanical Properties of Wire and Arc Additive Manufactured Inconel 625. JOM 2019, 71, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindermann, R.M.; Roy, M.J.; Morana, R.; Francis, J.A. Effects of microstructural heterogeneity and structural defects on the mechanical behaviour of wire+ arc additively manufactured Inconel 718 components. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 839, 142826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Qiu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Z.; Muránsky, O.; Ionescu, M.; Pan, Z.; Xi, J.; Li, H. On the Effect of Heat Input and Interpass Temperature on the Performance of Inconel 625 Alloy Deposited Using Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing–Cold Metal Transfer Process. Metals 2021, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hönnige, J.R.; Colegrove, P.A.; Ganguly, S.; Eimer, E.; Kabra, S.; Williams, S. Control of residual stress and distortion in aluminium wire + arc additive manufacture with rolling. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 22, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmuhilan, M.; Kumanan, S. Effect of Inter-pass Layer Temperatures on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Inconel 625 Fabricated Using Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 1540–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maronek, M.; Sugra, F.; Bartova, K.; Barta, J.; Dománková, M.; Urminsky, J.; Pasak, M. The Effect of Interpass Temperature on the Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of Components Made by the WAAM Method from Inconel 718 Alloy. Metals 2024, 14, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, V.; Trujillo, L.; Gamon, A.; Arrieta, E.; Murr, L.E.; Wicker, R.B.; Katsarelis, C.; Gradl, P.R.; Medina, F. Comprehensive and Comparative Heat Treatment of Additively Manufactured Inconel 625 Alloy and Corresponding Microstructures and Mechanical Properties. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Singla, J.; Singh, V.; Singh, J.; Kumar, H.; Bansal, A.; Singla, A.K.; Goyal, D.K.; Gupta, M.K. Influence of post heat treatment on metallurgical, mechanical, and corrosion analysis of wire arc additive manufactured inconel 625. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 5910–5923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, K.E.K.; Srinivas, M.N.; Rajak, S. Wire arc additive manufacturing of aluminium alloys: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 41, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).