Abstract

Arduino-based sensor systems are gaining widespread adoption in modern technological applications due to their accessibility, low-cost components, diverse sensor compatibility, high reliability, and user-friendly programming. Because of these advantages, such a system was selected to monitor and control microclimate parameters in a small-scale experimental greenhouse. The greenhouse will cultivate several vegetable species in soils with varying zeolite concentrations. The aim of this paper is to present the design and prototype development of a sensor system capable of tracking key environmental parameters, including temperature, humidity, atmospheric pressure, and soil moisture, while also enabling automated irrigation.

1. Introduction

Embedded systems have become ubiquitous in modern technological applications, driven by their ability to perform dedicated tasks with high reliability and real-time responsiveness [1], particularly in industrial automation and IoT domains where deterministic operation is critical.

Unlike general-purpose computing architectures, embedded systems employ purpose-built designs that eliminate resource-intensive peripherals [2], instead utilizing optimized interfaces (e.g., MEMS sensor arrays, capacitive touch inputs) to achieve ultra-low-power operation (<1 W typical) and compact form factors, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of architectural features between general-purpose computing systems and embedded systems.

This architectural efficiency has enabled transformative adoption across vertical markets, particularly in precision agriculture, where distributed sensor networks require both energy autonomy and environmental robustness [3].

Within this landscape, the Arduino ecosystem has established itself as a paradigm-shifting platform for rapid prototyping and cost-optimized automation [4]. Its open-source architecture integrates three key innovation vectors: (1) a versatile microcontroller unit (MCU) with mixed-signal I/O capabilities (10-bit ADC, PWM outputs), (2) configurable digital/analog interfaces supporting over 20 sensor protocols (I2C, SPI, 1-Wire), and (3) modular expansion through standardized hardware shields (e.g., GSM, LoRa, PLC) and object-oriented software libraries [5]. This tripartite flexibility has enabled cross-domain solutions spanning from precision environmental monitoring to closed-loop robotic systems, with documented deployment in over 85% of academic prototyping projects [6].

However, Arduino’s accessibility comes with inherent constraints:

- Electrical limitations: TTL-level signals (0–5 V) and limited current sourcing (≤20 mA per pin) necessitate external circuitry (e.g., amplifiers, optoisolators) for industrial integration [7].

- Computational bounds: Finite memory and clock speeds restrict complex algorithms, often requiring optimization or hybrid architectures [8].

Despite these challenges, Arduino remains a preferred choice for experimental systems, as evidenced by its use in microclimate monitoring (e.g., [9,10]). This paper leverages Arduino’s strengths to address agritech needs, focusing on a low-cost sensor network for greenhouse automation—a critical step toward sustainable precision agriculture [11].

The primary application of this sensor system is going to be for monitoring and controlling microclimate parameters within a smart greenhouse, where multiple vegetable species will be cultivated in soils with varying zeolite concentrations.

Our sensor system employs real-time data logging to calibrate environmental parameters, ensuring operational stability.

2. Design and Development

The designed prototype integrates an Arduino Mega platform (Atmega2560 microcontroller) with the following components:

- Sensors:Resistive soil moisture sensors;

- -

- Temperature and humidity sensors (DHT22);

- -

- Barometric pressure sensor (BMP180).

- Data logging: SD card module storing measurements in Excel-compatible format

- Peripherals:

- -

- GPS module for geolocation tracking.

- -

- Real-time clock (RTC) for timestamping and background task scheduling.

- -

- Four-line LCD display for the control panel.

- Software Architecture:The embedded operating system was programmed in C++ (Arduino IDE) and features a control panel with the following menu options:

- -

- Sensor Status (real-time readings);

- -

- Temperature/Humidity Monitoring;

- -

- Time/Date Configuration (RTC sync);

- -

- Barometric Pressure Status;

- -

- GPS Coordinates;

- -

- File System Management (SD card data);

- -

- Environmental Actuators Schedule (fan/light triggering based on time thresholds);

- -

- System Info (firmware version, memory usage).

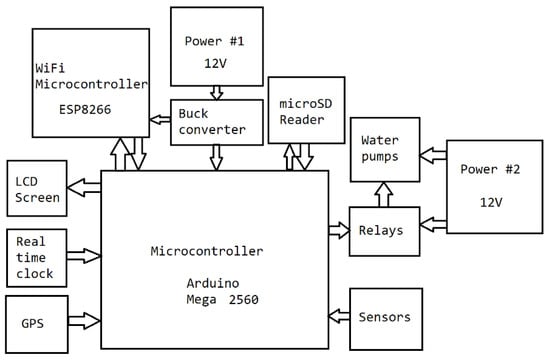

Detailed block diagram of the sensor system is presented in Figure 1. Figure 1. Block diagram of the sensor system.

Figure 1. Block diagram of the sensor system.

The Arduino Mega platform was selected as the core controller due to its

(1) Extensive GPIO pin count (54 digital I/O pins);

(2) High-density analog-to-digital conversion capability (16-channel 10-bit ADC);

(3) Expanded memory resources (256 KB flash, 8 KB SRAM)-critical features for simultaneous multi-sensor integration and data processing in our greenhouse monitoring system.

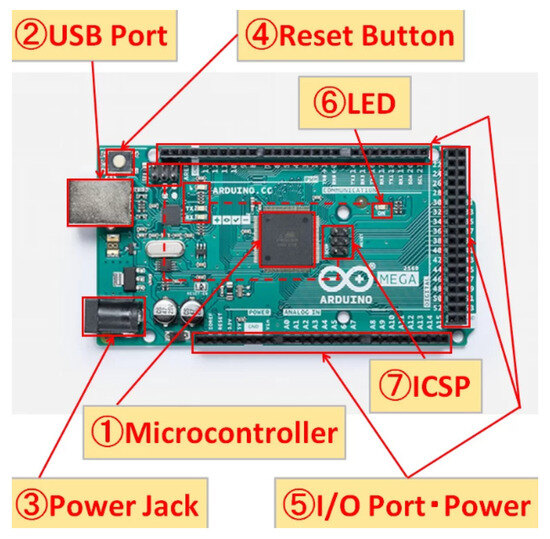

A general overview of the platform architecture is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

General overview of the Arduino Mega platform architecture.

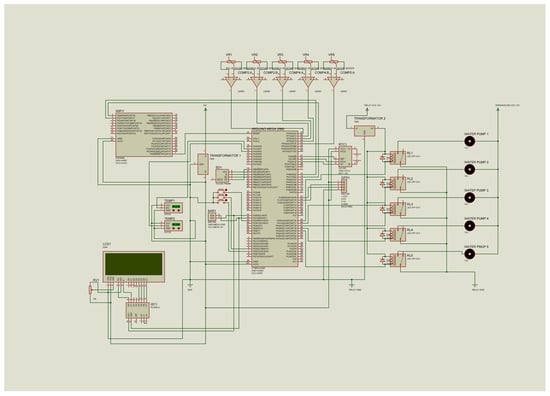

The schematic diagram (Figure 3) presents the full electrical implementation of the monitoring system.

Figure 3.

Full electrical diagram of the Arduino-based monitoring and controlling system.

To achieve full system functionality, the following peripheral components were selected and integrated

- A 20 × 4 character LCD (Liquid Crystal Display) with I2C interface (Figure 4).

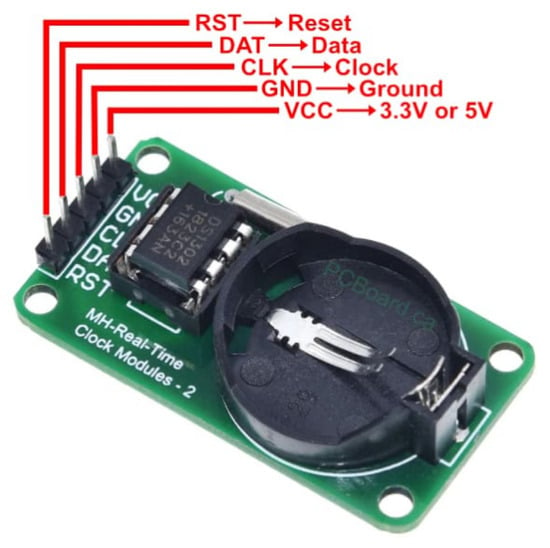

Real-time clock (RTC): The DS1302 model was chosen, which operates in Low Power Consumption mode and stores the time and date in Unix format. It communicates with the microcontroller via a three-channel serial interface (Data, Clock, Reset) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

A 20×4 character LCD.

Figure 5.

RTC-DS1302.

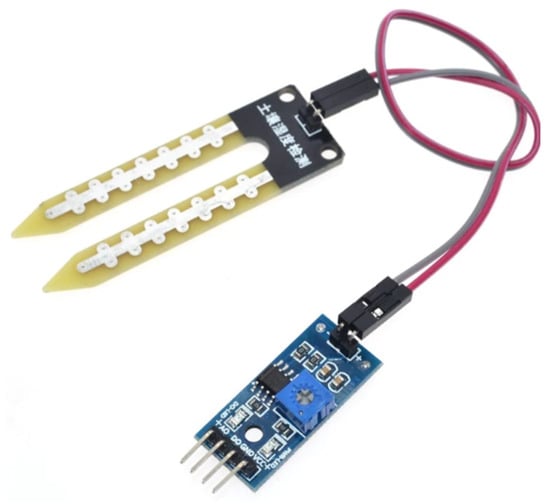

Resistive soil moisture sensor with operational amplifier conditioning (Figure 6). Table 2 shows its main characteristics.

Figure 6.

Resistive soil moisture sensor with operational amplifier.

Table 2.

Technical specifications—resistive soil moisture sensor.

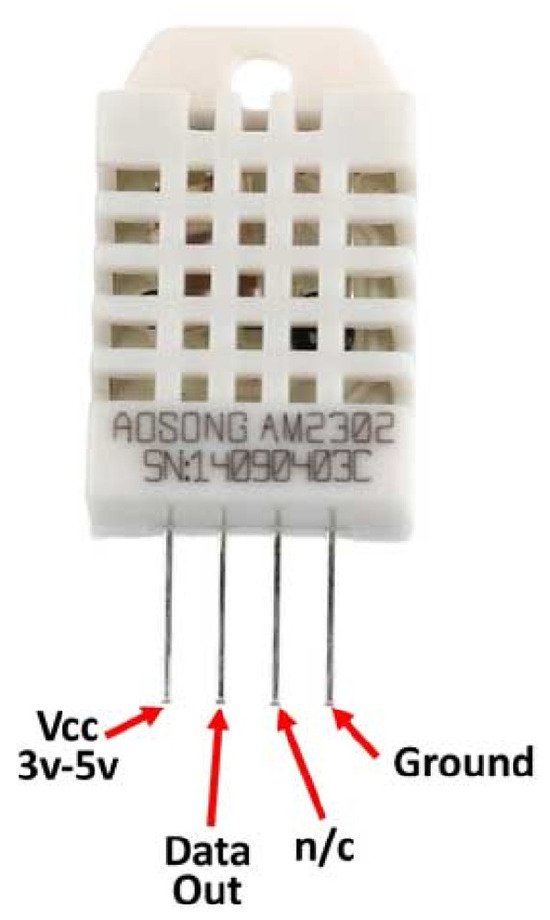

The system employs a DHT22 digital sensor for atmospheric measurements (Figure 7), with the following metrological characteristics (Table 3).

Figure 7.

DHT22 digital sensor.

Table 3.

Metrological characteristics of sensor DHT22.

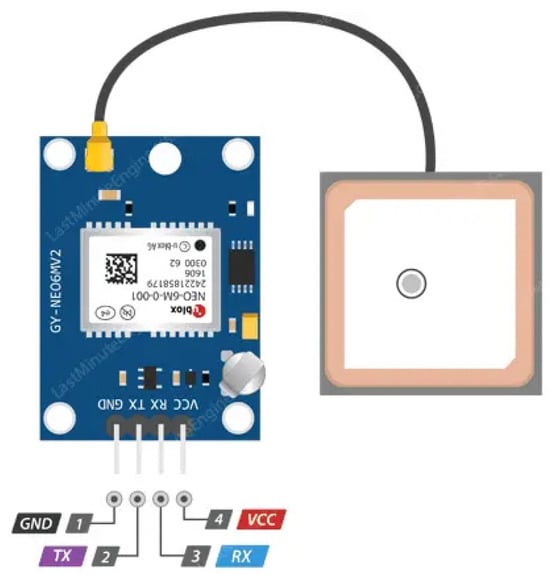

Figure 8.

U-blox NEO-6M GPS module.

Table 4.

Metrological characteristics of GPS module.

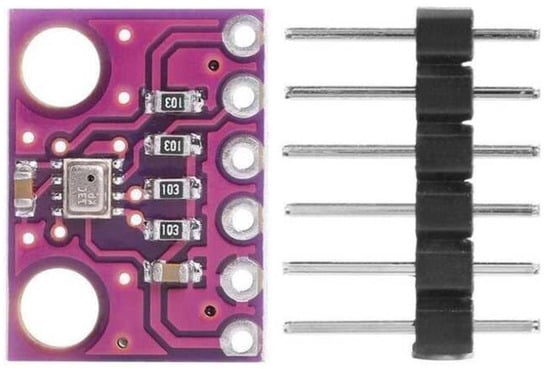

For atmospheric pressure monitoring the system incorporates a Bosch BMP280 digital barometric pressure sensor (Figure 9) with the technical specifications shown in Table 5).

Figure 9.

BMP 280 module.

Table 5.

Metrological characteristics of module BMP280.

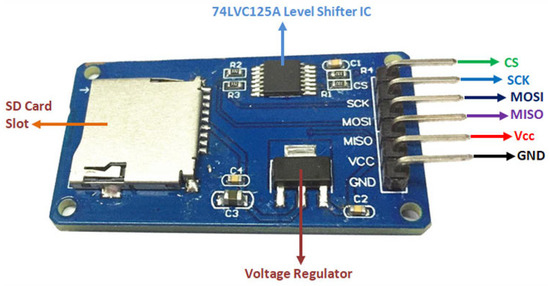

- The system implements an SPI-based SD card module for Excel-compatible data storage (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Micro SD card module.

Figure 10. Micro SD card module.

3. Results and Discussion

After the electrical circuit diagram of the sensor system for monitoring greenhouse parameters was synthesized and the individual modules and components were delivered, the system prototype was fully implemented. The system’s software was developed in C++. The capabilities provided by the sensor system are as follows:

When power is turned on, the user settings are loaded from the microcontroller’s EEPROM memory, and the main menu is displayed on the screen.

From the main menu, the user can select the following submenus: Start; Temperature; GPS; Real-Time Clock (RTC); Barometer; Data Storage; Greenhouse Environment Control; and System Information. The Temperature, GPS, and Barometer menus are read-only and contain no configurable settings. The Soil menu allows the user to check the moisture levels in each section, set the moisture percentage threshold for activating irrigation, and set the stop threshold for the irrigation pumps. The microcontroller uses this information to control the relay switches for the water pumps. The RTC menu enables the user to configure the system date and time, which are critical for the microcontroller’s timer functionality. The Data Storage menu is used to set the logging interval for sensor data storage. All sensor readings are saved on an SD card in tabular format. The Environment Control menu allows configuration of fan operation cycles (ON/OFF intervals) and configuration of artificial lighting (start/stop times). The System Information menu provides options for software updates and system reboot.

The system is powered by a 12 V battery with a corresponding battery charger. Future upgrades include the integration of solar panels and a solar charge controller. This enhancement will make the system mobile and fully autonomous.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we discussed the design of a sensor system which is capable of tracking key environmental parameters such as temperature, humidity, atmospheric pressure, and soil moisture. The irrigation process is MCU-controlled and thus fully automatic. The sensor system features input of user settings in order to perform the whole process of monitoring and sensing according to a user-defined scenario. Moreover, a physical prototype of the sensor system has been built and implemented.

The primary advantage of the proposed sensor system prototype lies in its ability to enable automated, real-time monitoring and precise control of environmental parameters within experimental greenhouse conditions.

As future upgrade of the system is regarded the integration of solar panels and solar charge controller. This enhancement will make the system mobile and fully autonomous.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation and data acquisition, I.B. and A.M.; investigation and writing—original draft preparation, I.B., A.M. and T.M.; conceptualization, validation, methodology and supervision, I.B., A.M. and T.M.; methodology, I.B., A.M., T.M. and E.K.; manuscript editing, E.K. and I.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the KP-06-N87/11 with the Research Fund/BG-175467353-2024-11-0287, funded by the Research Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Derler, P.; Lee, E.A.; Vincentelli, A.S. Modeling Cyber-Physical Systems. Proc. IEEE 2012, 100, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwedel, P. Embedded System Hardware. In Embedded System Design; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Chapter 3; ISBN 978-3-030-60910-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, C.M.; Myburgh, H.C. An Intra-Vehicular Wireless Multimedia Sensor Network for Smartphone-Based Low-Cost Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems. Sensors 2022, 22, 3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banzi, M.; Shiloh, M. Advanced Input and Output. In Getting Started with Arduino, 4th ed.; Make Community, LLC: Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 2022; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- Widhalm, D.; Goeschka, K.M.; Kastner, W. An Open-Source Wireless Sensor Node Platform with Active Node-Level Reliability for Monitoring Applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 7613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J. Quantifying the Value of Open Source Hardware Development. Mod. Econ. 2015, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drymonitis, A. Introduction to Arduino. In Digital Electronics for Musicians; Maker Innovations Series; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Guerra, L.H.; Leal-Flores, A.J. Potentializing the problemsolving competence in programming courses through a practice-based learning + tutoring strategy. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Porto, Portugal, 27–30 April 2020; pp. 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Marín, A.M.; Sánchez-Vívas, D.F.; Duarte-Carvajalino, J.M.; Góez-Vinasco, G.A.; Araujo-Carrillo, G.A. Estimating Carrot Gross Primary Production Using UAV-Based Multispectral Imagery. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhao, L.; Liang, C.; Cui, N.; Gong, D.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Hu, X.; Zou, Q. Comparison of Satellite-Based Models for Estimating Gross Primary Productivity in Agroecosystems. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 297, 108253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanavaram, B.; Reddy, E.M.K.; Rashmi, M.K. Arduino based Automation of Agriculture A Step towards Modernization of Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Electronics Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA), Coimbatore, India, 5–7 November 2020; pp. 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).