Abstract

This study explores the design, synthesis and preliminary in silico screening of novel thiadiazole-isatin hybrid derivatives targeting diabetes mellitus. Building on thiadiazole and isatin compounds’ demonstrated antidiabetic potential, the research objectives were to design and synthesize thiadiazole-isatin hybrids and evaluate their antidiabetic potential. The methodology encompassed a literature review, computational screening using “molecular docking, ADME prediction, Lipinski’s rule”, and the synthesis of thiadiazole intermediates from thiosemicarbazide combined with isatin derivatives. The key findings revealed that compounds 2a and 2b exhibit favorable binding affinity with “human aldose reductase, monoglyceride lipase, GLP-1, and alpha-amylase”, satisfying Lipinski’s rule for optimal drug likeness. Docking scores ranged from −10.6 to −7.0 for 2a and −10.2 to −7.0 for 2b. Thiadiazole-isatin derivatives, particularly 2a and 2b, demonstrate promise as antidiabetic agents through multi-enzyme inhibition, warranting pre-clinical and in vitro validation. This research offers a novel therapeutic strategy for diabetes management and potential pharmaceutical lead compounds. Future directions include experimental validation, in vitro and in vivo efficacy studies, and structure–activity relationship exploration, contributing to innovative antidiabetic therapies.

1. Introduction

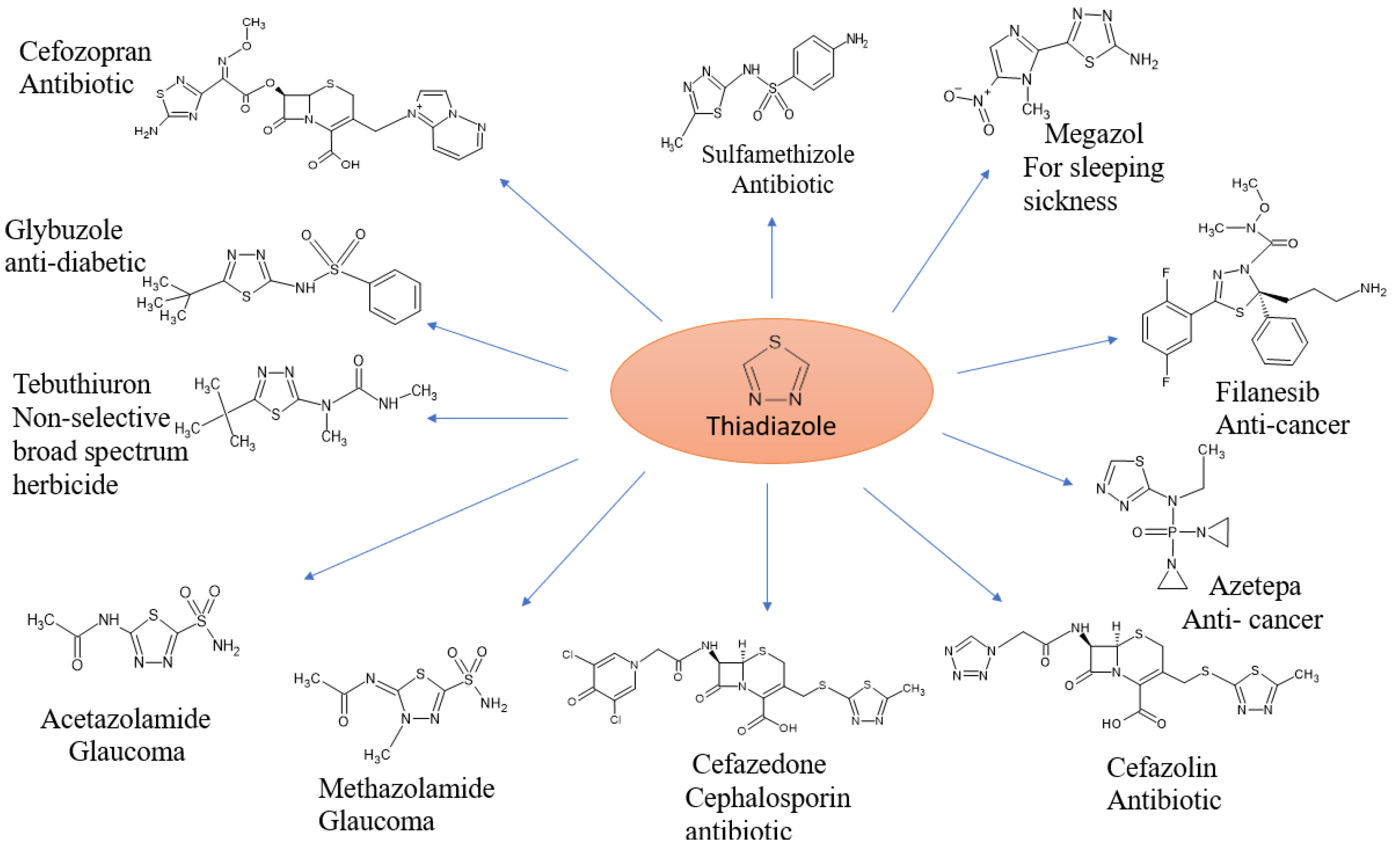

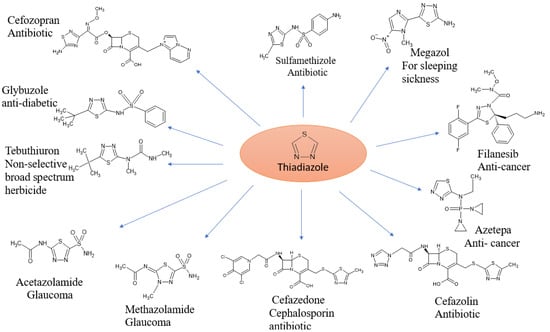

Heterocyclic substances have garnered much interest due to several of their significant biological and therapeutic uses. Because heterocyclic molecules are useful and have been extensively studied synthetically, research interest on them is growing quickly.Nearly 90% of new drugs contain them, and they are found across chemistry and biology, where a lot of scientific study and usage takes place [1]. Heterocyclic compounds are of great interest in organic chemistry as they have “strong coordination ability, high electron-blocking capacity”, and a wide range of applications [2]. In medical chemistry, heterocyclic molecules are primarily of interest. Together with the mother scaffold’s effective substituent groups, the ring structures’ size and type clearly demonstrate their physicochemical characteristics [3]. “Heterocyclic” comes from “heteros”, a Greek word that means “distinct.” These substances are essentially organic cyclic structures that contain a heteroatom. Common heteroatoms include nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur; other elements such as Se, P, Si, and B can additionally combine to form heterocyclic molecules [4]. In addition, they are widely distributed in natural and synthetic bioactive compounds, such as “alkaloids, antibiotics, amino acids, vitamins, hormones, hemoglobin, dyes”, and many other therapeutic agents [5]. “Alkaloids, cardiac glycosides, antibiotics, and insecticides” are some of the heterocycles of importance to human and animal health. In aromatic rings where a carbon has been substituted by a heteroatom from a N or S family, the electron pair donation availability, and electronegativity difference that characterizes these closed-ring systems, are fundamental in circular systems [6]. Nitrogen heterocycles are the most essential pharmacophores and a significant class of compounds; however, sulfur-containing heterocycles are frequently present in FDA-approved drugs, and are reported to possess various “anticancer, antimicrobial, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, anti-Alzheimer’s, and antifungal activities” [7]. One sulfur atom and two nitrogen atoms make up the framework of the thiadiazole chain. Thiadiazole has 4 distinct isomeric structures. One of the most prevalent and significant components found in the fundamental structure of an array of natural goods and medications is thiadiazole. Since the discovery of powerful sulfa medications that include this nucleus, the pace of advancement pertaining to thiadiazole has significantly increased. Thiadiazole and its derivatives are well known for being important scaffolds in pharmacology. ‘1-3-4-thiadiazoles’ show a variety of inhibitory activities, encompassing enzymes and inhibitors of human platelet aggregation, as well as inhibitors that are antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antioxidant, antitubercular, neuroprotective, and antiviral. These compounds have exceptional pharmacological applications. Some drugs are available on the market containing the thiadiazole moiety. Additionally, some natural products, including polycarpathiamines (A) and (B), in which dendrodoine was taken from the Ascidian Polycarpa aurata., which is derived from Penicillium thiamines B and the marine algae Dendrodoa grossularia (13) (which come from Penicillium oxalicum via extraction), contain the 1,2,4-thiadiazole nucleus, as demonstrated [8]. Fischer originally described 1,3,4-thiadiazoles in 1882, and Busch went on to develop them. Thiadiazoles with amino, hydroxyl, and mercapto substituents can take on a variety of tautomeric forms. In its completely conjugated form, the ring of the 1,3,4-thiadiazole structure, which contains three different types of atoms, does not exhibit tautomerism. However, tautomerism is achievable in the presence of specific substituents. Because of the S (sulfur) atom’s inductive effect, this base is incredibly weak with a reasonably elevated aromaticity, the 1,3,4-thiadiazole ring. While it can experience ring cleavage with an aquatic foundation, in aqueous acid solutions, it is reasonably stable. The thiadiazole ring system is a versatile heterocyclic scaffold widely used in medicinal chemistry due to its diverse biological activities, as illustrated in Figure 1. Additionally, the ring is demonstrated to be extremely electron-poor because of the nitrogen atoms effect of electron withdrawal, making it largely resistant to electrophilic substitution, while vulnerable to assault by nucleophiles. Conversely, the ring becomes very active, and reacts rapidly to generate an assortment of derivatives when substitutions were introduced at its 5′ and 2′ locations [9].

Figure 1.

Representative medicinal scaffolds featuring the thiadiazole ring system.

Rationale of Design

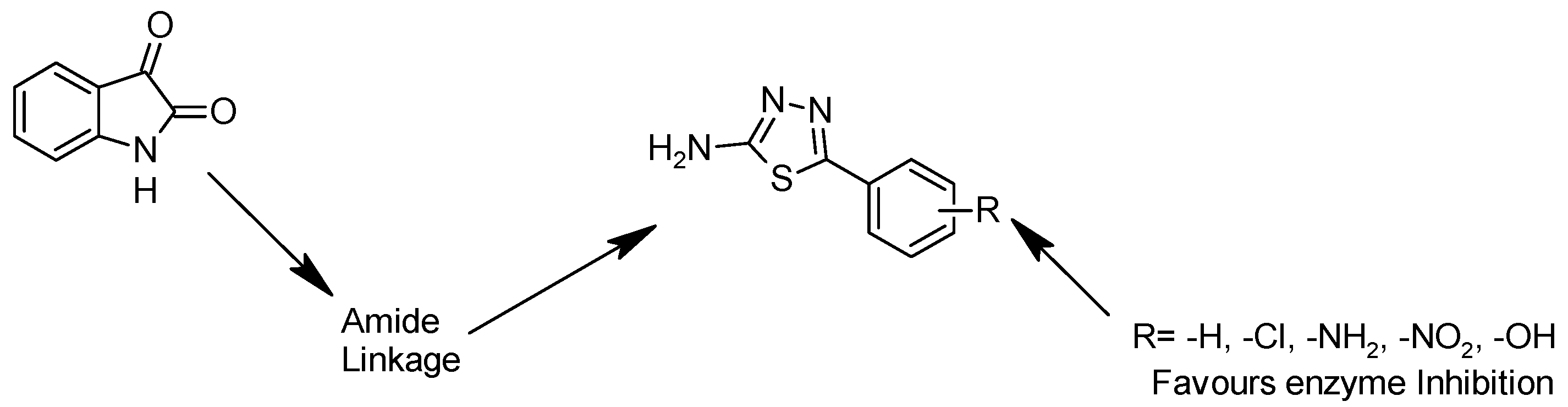

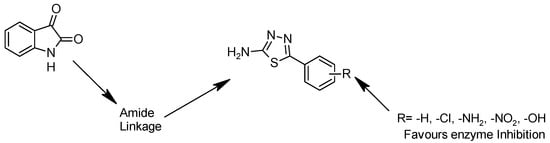

Isatin is an important heterocyclic scaffold with diverse pharmacological properties. Structural modification through an amide linkage to bioactive 1,3,4-thiadiazoles enhances rigidity and target interactions. The substituted thiadiazole ring adds pharmacophoric features, improving binding affinity. Aromatic substituents (R = –H, –Cl, –NH2, –NO2, –OH) modulate activity by influencing electronic and steric properties. Thus, isatin–amide–thiadiazole conjugates are expected to show significant enzyme inhibitory activity through combined pharmacological potential and substituent fine-tuning. The 1,3,4-thiadiazole scaffold was selected due to its favorable electronic properties, bioisosteric behavior, and ability to enhance biological activity. The rationale underlying the selection and modification of the 1,3,4-thiadiazole compound is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Rationale of 1,3,4-thiadiazole compound.

2. Materials and Methods

The designed compounds were evaluated through in silico analysis for antidiabetic activity (aldose reductase and MAGL) and further synthesized for in vitro efficacy studies. Computational tools confirmed their pharmacological, physicochemical, and bioactivity properties, supporting their selection for synthesis. Solvents (LR grade) from Central Drug House Pvt. Ltd., E. Merck, and S. D. Fine Chemicals Ltd. were purified prior to use. Melting points were determined by the capillary method. IR spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu IR Affinity-1 FTIR spectrophotometer, and 1H NMR spectra on a Bruker DRX-300/400 spectrometer using TMS as an internal standard in DMSO/CDCl3. Ethanol (99.5%) was employed, obtained from rectified spirit (95.6%) through purification to absolute ethanol. The proposed research work can be broadly divided into two parts. The first part was based on design and synthetic work, while the second part dealt with the physicochemical evaluation and chemical docking of the substances. Various derivatives of 5-phenyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-amine were prepared (1a–1f) on reaction with isatin, yielding substituted amides as the final products.

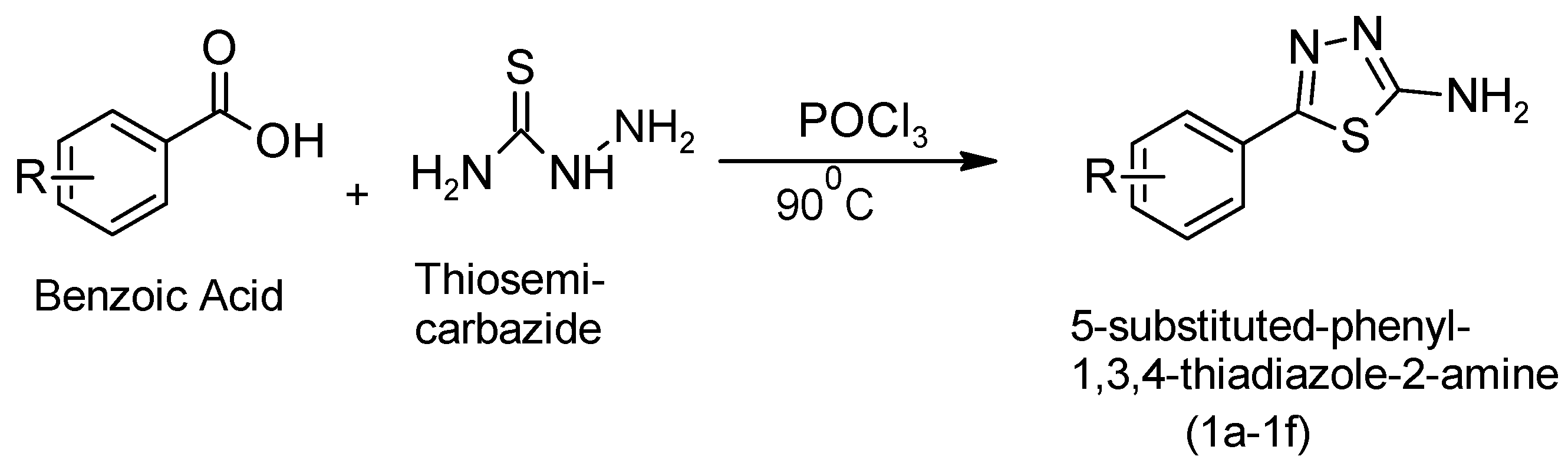

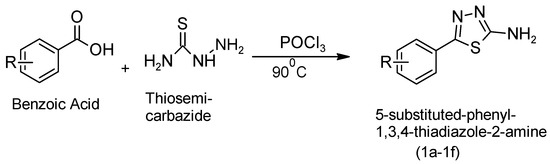

- Synthesis of 5-phenyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-amine (1a–1f):

Series 1a–1f: Benzoic acid (0.1 mol) and thiosemicarbazide (0.1 mol) were gently refluxed in 30 mL of phosphorous oxychloride for 30 min. Next, the mixture took time to cool before water (90 mL) was carefully added. The mixture of DMF and ethanol (9:1) was filtered, dried, and crystallized, yielding a white solid in 65% yield. After the solid separated, it was collected by filtration, resuspended in water, and then made basic with aqueous KOH to isolate the final product [10,11]. The synthesis of 5-phenyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-amine was initiated through a key reaction step, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Synthetic reaction to obtain 5-phenyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-amine as the first step.

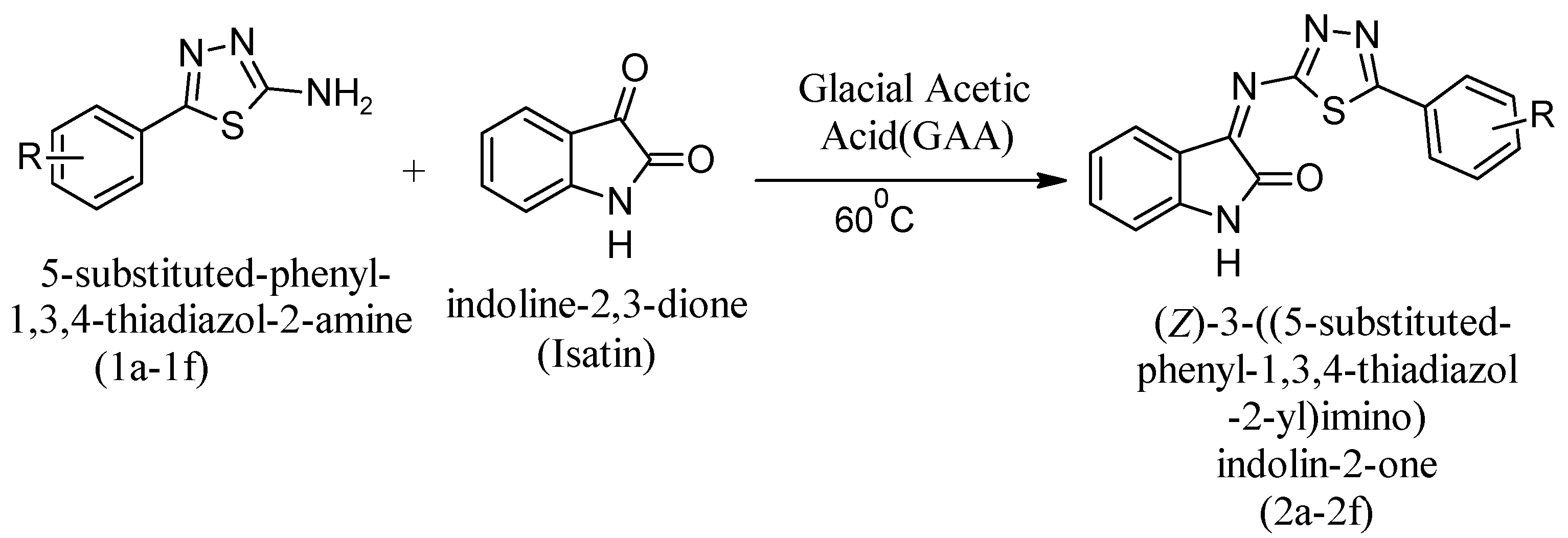

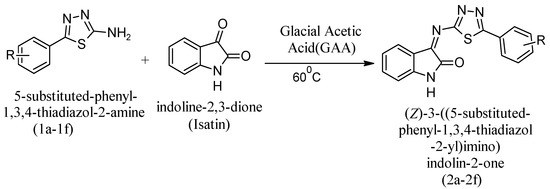

- Synthesis of the Final 1,3,4-Thiadiazole Derivatives (2a–2f):

In the 100 mg, 0.0036 mole solution in ethanol (20 mL), Isatin (0.52 gm) was added and reflux was introduced for condensation. 60 °C was the constant outside temperature. When condensation of the mixture began, GAA was introduced to the mixture to provide acidic conditions. Monitoring of the reaction was performed by TLC in DCM:MeOH (9:1). After confirmation of the final product, the reaction mixture was kept at room temperature. The reaction mixture underwent a neutralization reaction via concentration from ice in an ice bath. A solid precipitate formed after complete neutralization, and the final product was obtained by filtering, washing with water, drying, and recrystallizing with ethanol. The final step of the synthetic pathway involved the preparation of substituted 5-phenyl-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2-amine derivatives, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Synthetic reaction to obtain substituted 5-phenyl-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2-amine derivates as the final compounds.

3. Result

- Chemistry

Each one of the designed compounds was examined via in silico computational analysis for their antidiabetic activity (aldose reductase and monoacylglyceryl lipase (MAGL)). These products underwent additional synthesis, and the resulting in vitro efficacy was investigated. All the designed compounds were also accepted by other online computational tools for pharmacological activities, physicochemical properties, and bioactivity properties. Hence, they were chosen for synthesis as per the given reaction scheme.

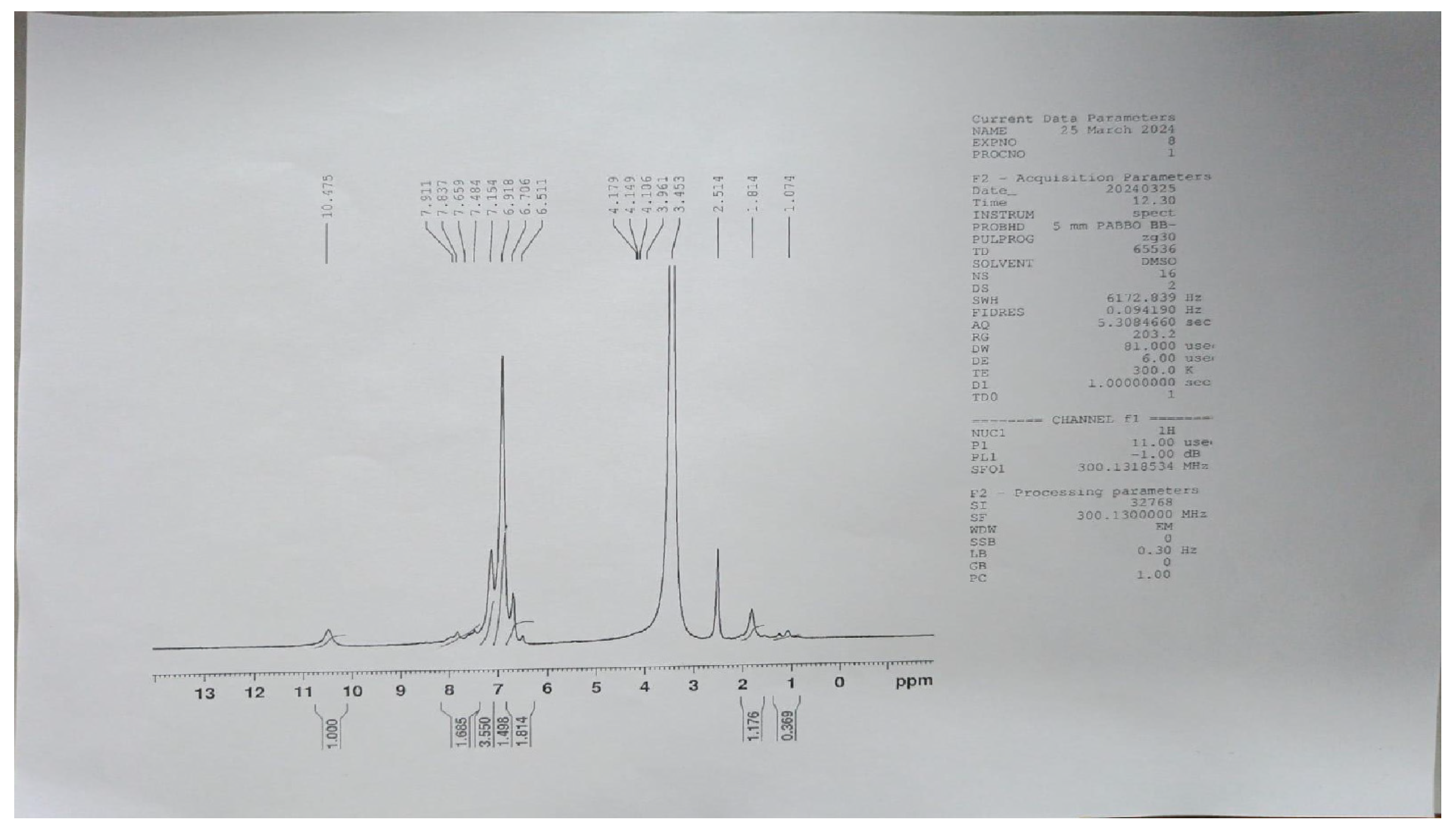

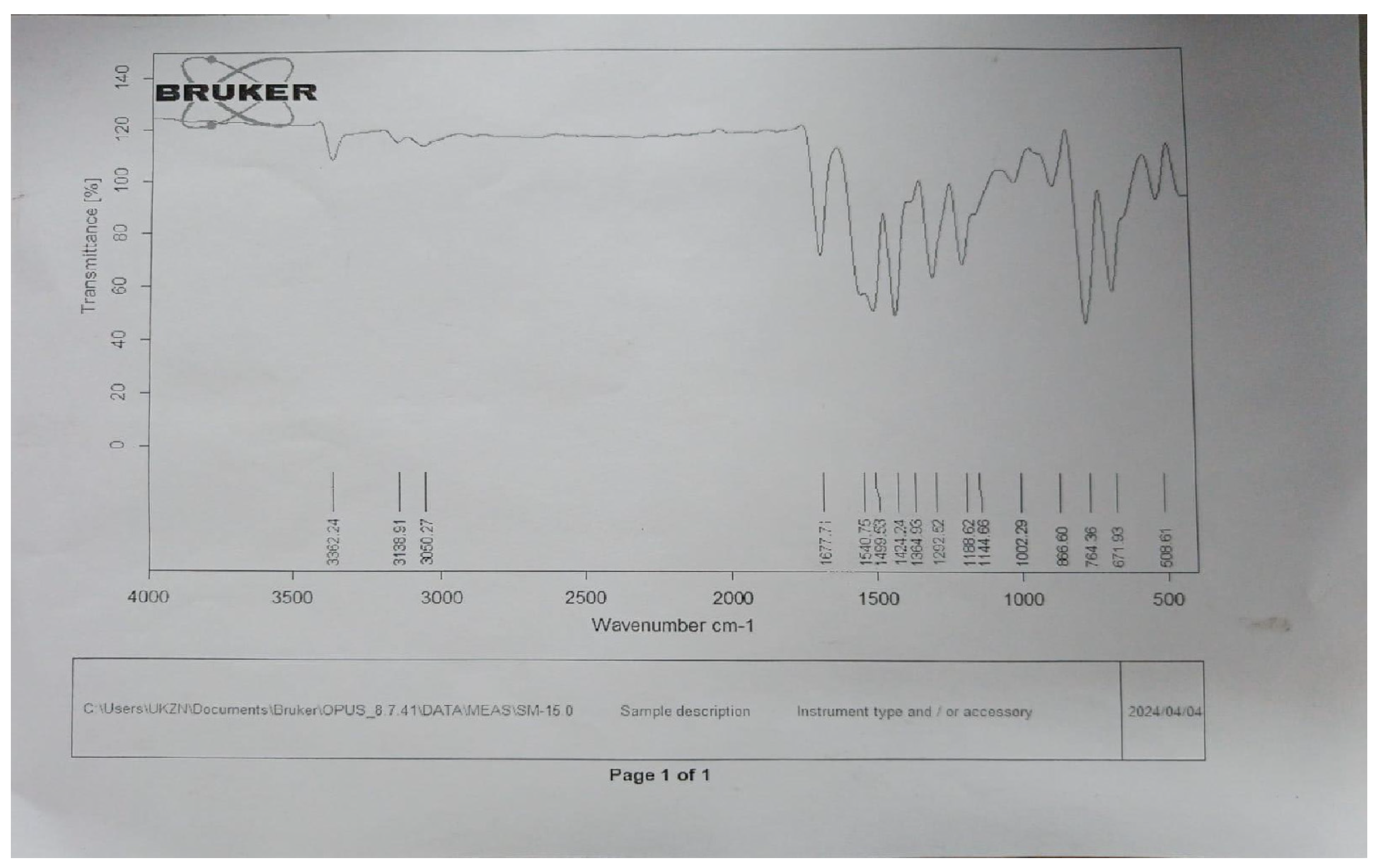

(Z)-3-((5-phenyl-1,3,4-thidiazole-2-yl)imino)indolin-2-one synthesis process (2a) Yield: 35%, M.P.: 160 °C, Appearance: White crystals, 1H NMR (400 MHz): δ 7.33 (1H, ddd, J = 7.8, 7.6, 1.2 Hz), 7.52-7.76 (5H, 7.58 (ddd, J = 8.2, 1.2, 0.4 Hz), 7.60 (dddd, J = 7.8, 7.4, 1.3, 0.4 Hz), 7.61 (tdd, J = 7.4, 1.6, 1.5 Hz), 7.69 (ddd, J = 8.2, 7.6, 1.5 Hz)), 8.06 (2H, dtd, J = 7.8, 1.5, 0.4 Hz), 8.93 (1H, ddd, J = 7.8, 1.5, 0.4 Hz). IR(cm−1): 3462(N-H, Stretch), 3075-3110(C-H, Stretch), 1769(C=O, Stretch), 1672(C=N, Stretch), 1604(C=C, Bend), 1496 (C=C, Stretch), 1342 (C-N Stretch), 1265 (N-N, Stretch).

(Z)-3-((5-(2-chlorophenyl)-1,3,4-thidiazole-2-yl)imino)indolin-2-1 (2b) Yield: 36%, M.P.: 180 °C, Appearance: Brownish Crystals, 1H NMR (400 MHz): δ 7.32 (1H, ddd, J = 7.8, 7.6, 1.2 Hz), 7.45–7.87 (5H, 7.53 (ddd, J = 7.9, 7.6, 1.7 Hz), 7.57 (ddd, J = 8.2, 1.2, 0.4 Hz), 7.62 (td, J = 7.6, 1.2 Hz), 7.68 (ddd, J = 8.2, 7.6, 1.5 Hz), 7.80 (ddd, J = 7.9, 1.2, 0.4 Hz)), 8.06 (1H, ddd, J = 7.6, 1.7, 0.4 Hz), 8.92 (1H, ddd, J = 7.8, 1.5, 0.4 Hz).

(Z)-3-((5-(4-nitrophenyl)-1,3,4-thidiazole-2-yl)imino)indolin-2-1 (2c) Yield: 38%,M.P.: 170 °C, Appearance: Brownish crystals, 1H NMR (400 MHz): δ 7.42–7.58 (2H, 7.49 (ddd, J = 7.5, 7.1, 1.9 Hz), 7.52 (ddd, J = 7.9, 1.9, 0.5 Hz)), 8.01–8.18 (3H, 8.08 (ddd, J = 7.9, 7.5, 1.5 Hz), 8.12 (ddd, J = 8.8, 1.6, 0.5 Hz)), 8.26 (2H, ddd, J = 8.8, 1.5, 0.5 Hz), 8.67 (1H, ddd, J = 7.1, 1.5, 0.5 Hz).

(Z)-3-((5-(3,5-Dinitrophenyl)-1,3,4-thidiazole-2-yl)imino)indolin-2-1 (2d) Yield: 40%, M.P.: 190 °C, appearance: Yellowish crystal, 1H NMR (400 MHz): δ 7.42–7.60 (2H, 7.49 (ddd, J = 7.5, 7.0, 1.9 Hz), 7.54 (ddd, J = 8.0, 1.9, 0.5 Hz)), 8.01 (1H, ddd, J = 8.0, 7.5, 1.4 Hz), 8.54 (1H, ddd, J = 7.0, 1.4, 0.5 Hz), 8.88 (1H, t, J = 1.7 Hz), 9.00 (2H, dd, J = 1.7, 1.3 Hz).

(Z)-3-((5-(4-aminophenyl)-1,3,4-thidiazole-2-yl)imino)indolin-2-1 (2e) Yield: 42%, M.P.: 195 °C, Appearance: Pale yellow crystal, 1H NMR (400 MHz): δ 6.78 (2H, ddd, J = 8.3, 1.2, 0.4 Hz), 7.28–7.46 (2H, 7.34 (ddd, J = 8.2, 1.3, 0.4 Hz), 7.40 (td, J = 7.6, 1.3 Hz)), 7.64–7.81 (3H, 7.70 (ddd, J = 8.3, 1.7, 0.4 Hz), 7.73 (ddd, J = 8.2, 7.6, 1.5 Hz)), 8.58 (1H, ddd, J = 7.6, 1.5, 0.4 Hz).

(Z)-3-((5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,3,4-thidiazole-2-yl)imino)indolin-2-1 (2f) Yield: 45%, M.P.: 200 °C, Appearance: Whitish crystal, 1H NMR (400 MHz): δ 7.16 (2H, ddd, J = 8.6, 1.2, 0.4 Hz), 7.29–7.47 (2H, 7.35 (ddd, J = 8.2, 1.3, 0.4 Hz), 7.41 (td, J = 7.6, 1.3 Hz)), 7.61–7.79 (3H, 7.69 (ddd, J = 8.2, 7.6, 1.5 Hz), 7.73 (ddd, J = 8.6, 1.7, 0.4 Hz)), 8.90 (1H, ddd, J = 7.6, 1.5, 0.4 Hz).

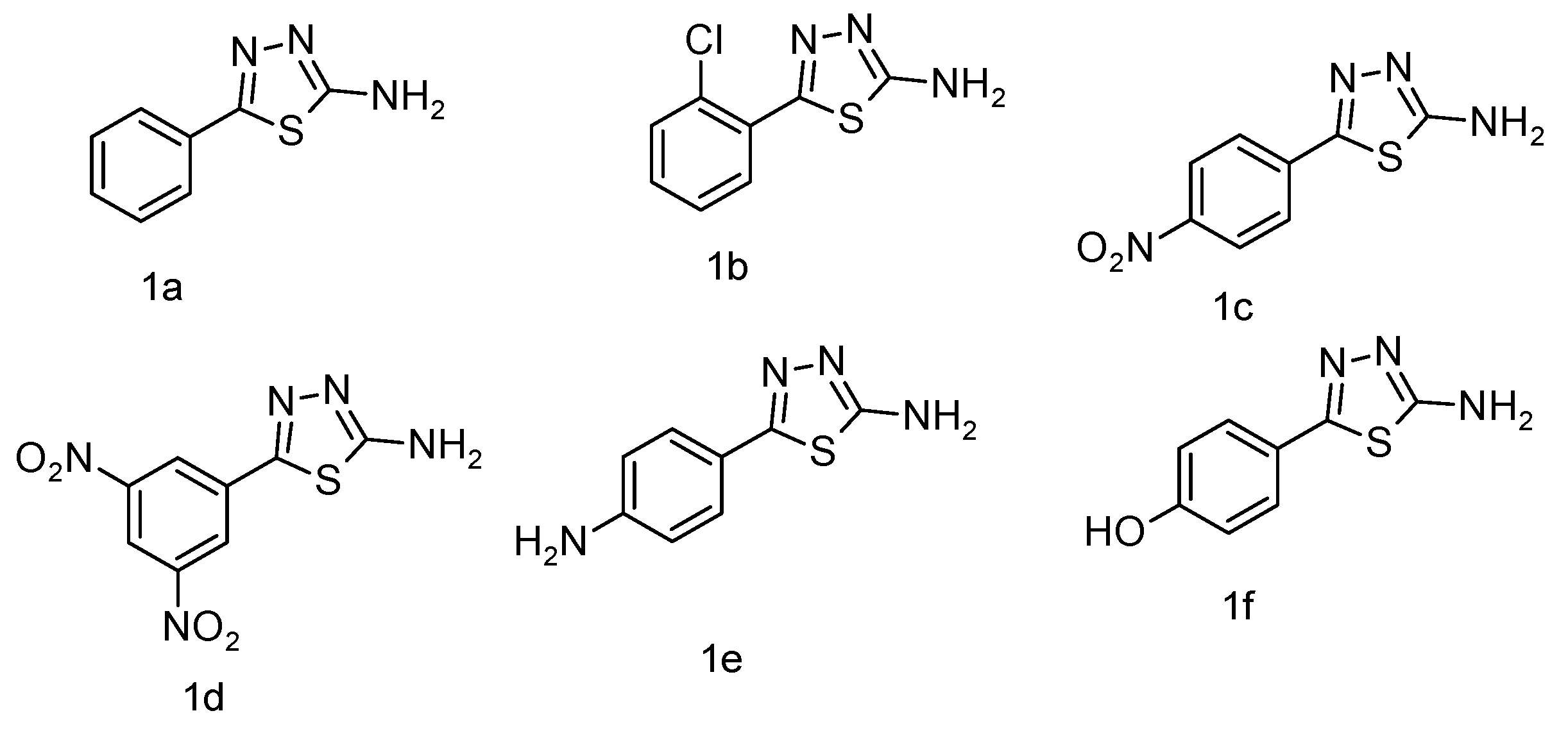

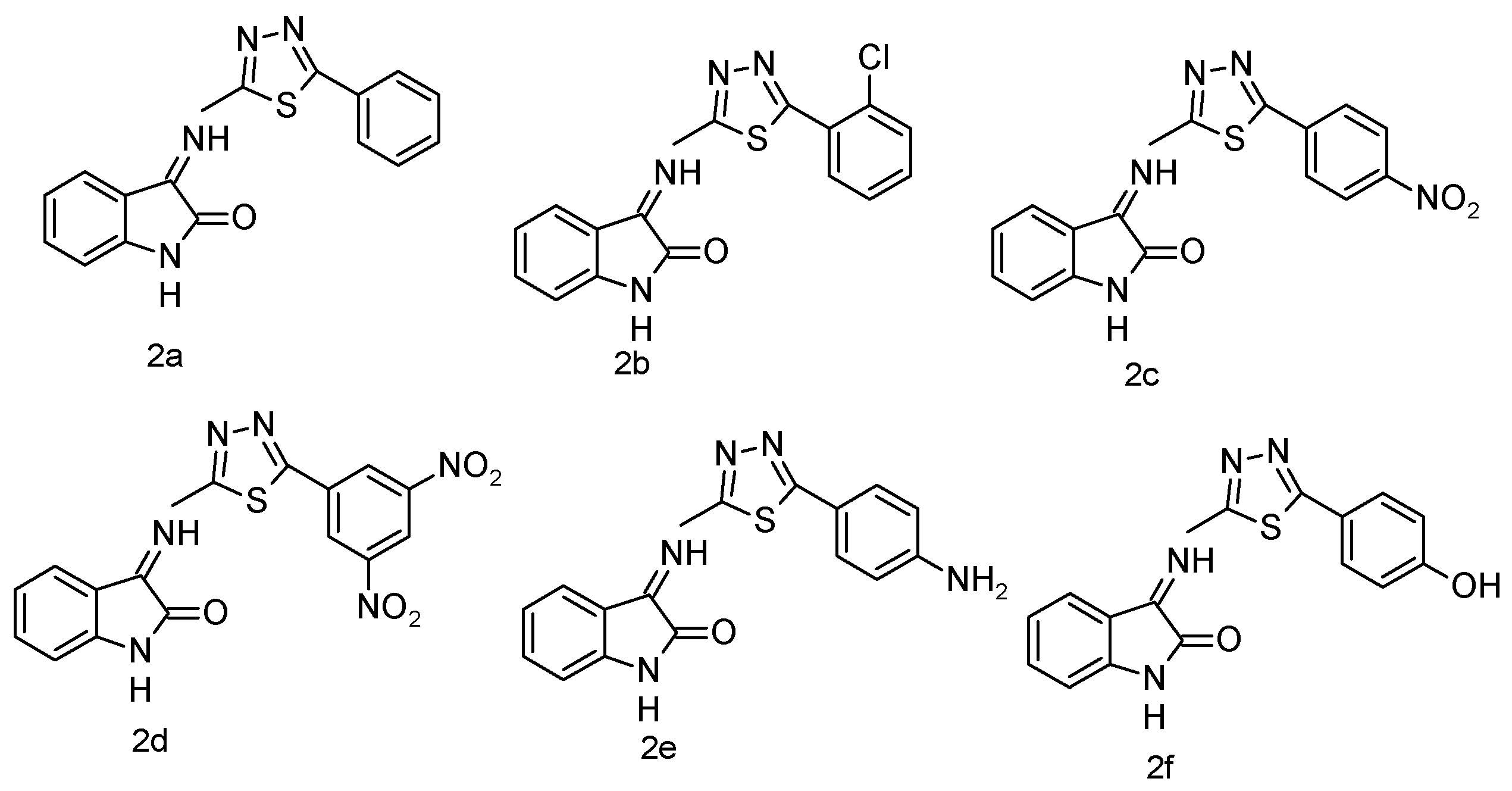

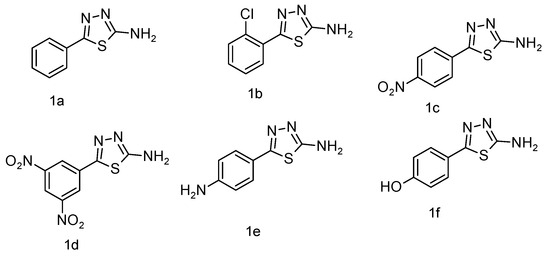

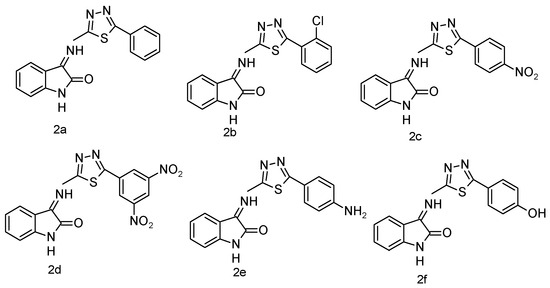

The IR spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu IR Affinity-1 FTIR spectrophotometer (KBr disc method). The ^1H NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker DRX-300/400 using DMSO or CDCl3 with TMS as the internal standard. Signal patterns were designated as d, t, q, m, s, and bs with chemical shifts in δ (ppm). The ^1H-NMR spectrum strongly supports the synthesis of the target compound. A singlet at δ 5.60 ppm corresponds to methylene (–CH2–) protons introduced during the coupling of benzotriazole with quinoline carbohydrazide, serving as a structural marker. The absence of this resonance in the starting materials confirms the new –CH2– linkage. The downfield shift (δ 5.60 ppm) arises from deshielding by adjacent N and C=O groups, substantiating the connectivity. Thus, the methylene proton peak provides unambiguous evidence for the successful formation of the isatin-thiadiazole GI hybrid system. Both IR and 1H-NMR spectra of the most potent compound are presented in Appendix A and Appendix B. The chemical structures of the synthesized 5-phenyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-amine derivatives (1a–1f) are presented in Figure 5. The chemical structures of the final 1,3,4-thiadiazole derivatives are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Compounds of 5-phenyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-amine (1a–1f).

Figure 6.

Final derivatives of 1,3,4-thiadiazole.

3.1. Molecular Docking Studies

Molecular docking was performed using Glide 7.0, with Schrödinger suite version 10.1 used to generate ligand interaction diagrams and visualize protein–ligand interactions. Glide XP docking was employed after minimizing ligand energy, and docking was performed to obtain binding affinities. The binding energy, which reflects the strength of ligand–protein interaction, was used to identify the best configuration for each target. Molecules with the highest binding affinity for each protein were selected for further analysis. The PDB IDs used as antidiabetic targets were 1US0 (aldose reductase), 4W93 (alpha amylase), 5UZN (monoglycerol lipase), and 3IOL (glycogen like protein). The molecular docking scores of the synthesized compounds against all four targets are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Molecular docking score of synthesized compounds with all four targets.

3.2. Physicochemical Studies

Predicting physicochemical characteristics is important in developing antidiabetic medications with improved pharmacological profiles. The toxicity, digital pharmacological action, physico-chemical properties, and oral bioavailability of the developed molecules were assessed using Molinspiration and Property Explorer. The molecular weight (MW), lipid solubility (cLogP), hydrophilicity (clogS), toxicity, number of rotatable bonds (nROTB), drug likeness, and Lipinski’s rule were computed. Toxicities predicted by Osiris Property Explorer and Data Warrior indicated no mutations, tumors, irritation, or adverse effects on reproduction. Higher lipophilicity with low water solubility is a key characteristic for improved pharmacological profiles. All synthesized compounds had solubility (clogS) within the satisfactory range (<−4). Lipophilicity-related clogP quantifies drug-likeness, effectiveness, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity, with favorable profiles at values less than 5. TPSA values were computed, showing poor membrane permeability and low CNS bioavailability, though values greater than 60 Å are chosen for oral molecules. Compounds with negative or null drug likeness values were excluded. These tools help screen active compounds.

Analyzing and Screening ADME Results

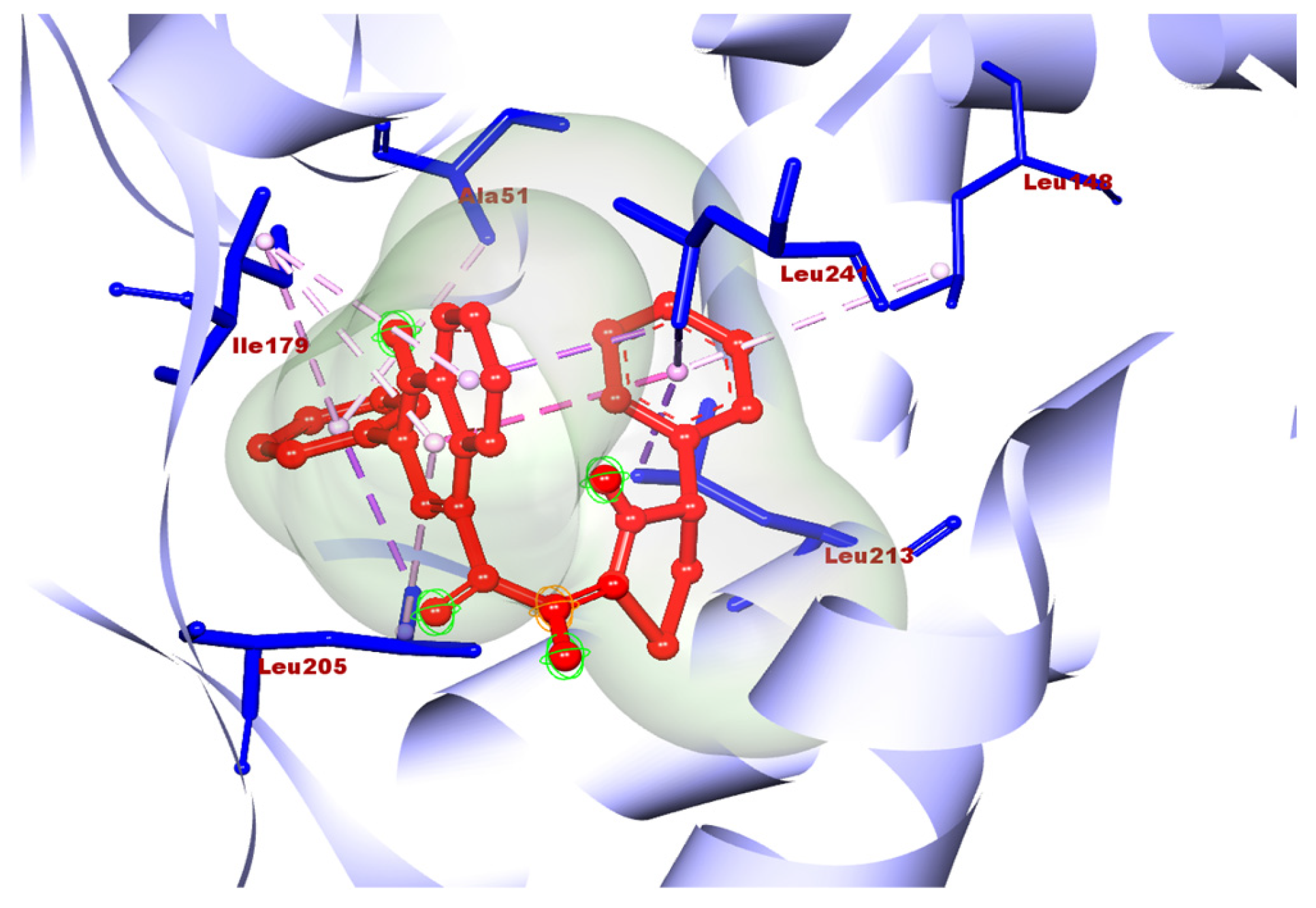

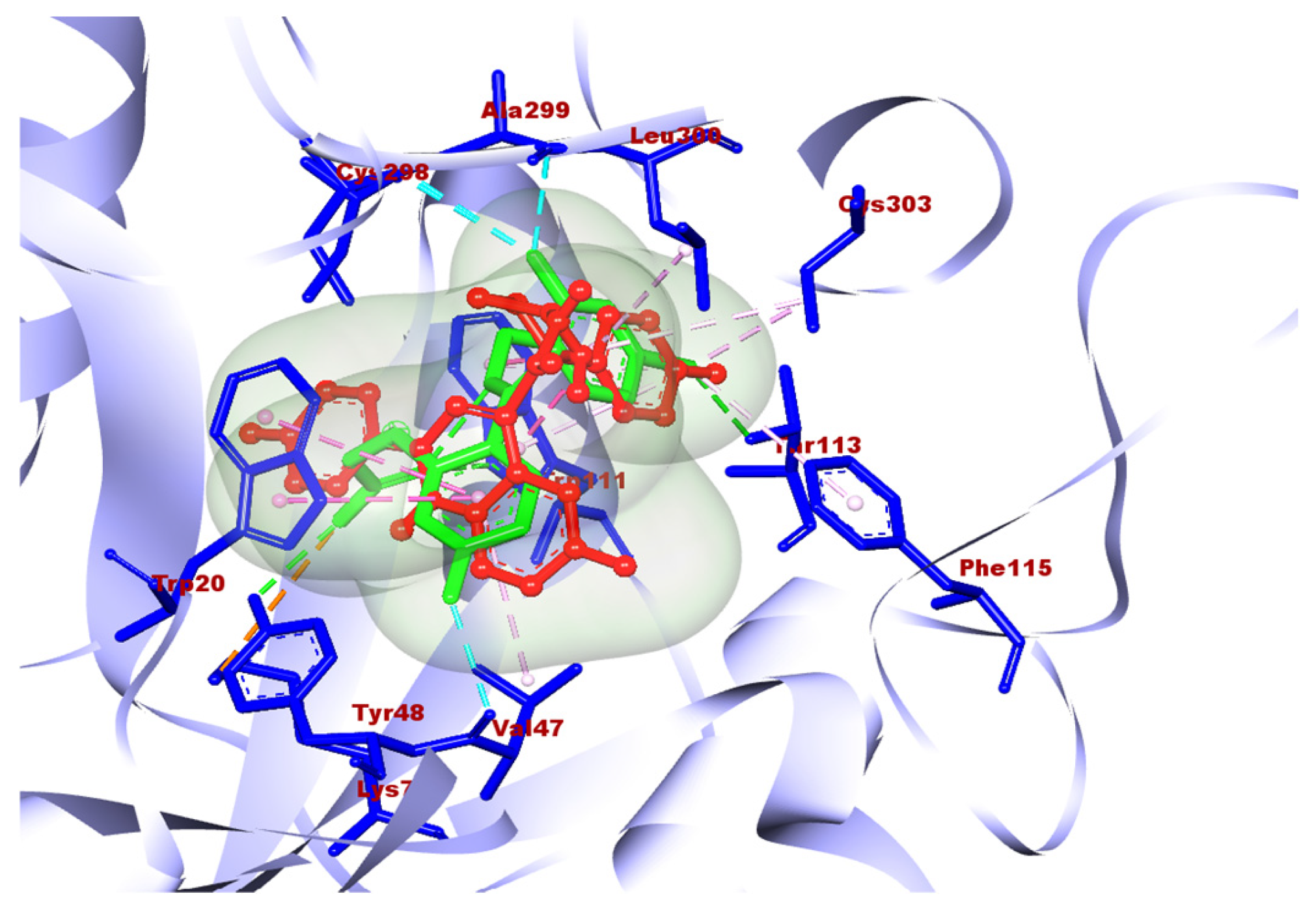

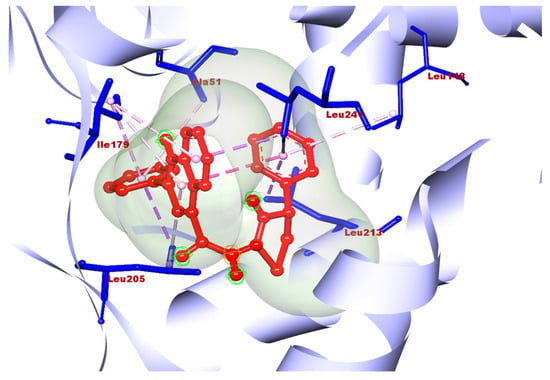

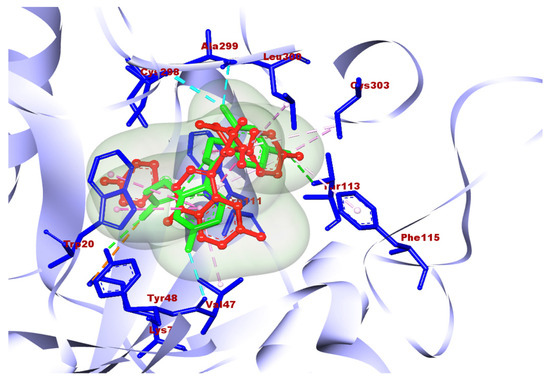

Molecule 2a showed good docking scores with the receptors human aldose reductase and monoglyceride lipase. 2a showed docking scores of −10.6, −9.8, and −7.4 with human aldose reductase, monoglyceride lipase, and GLP-1, respectively. However, a poor score (–6.8) was observed with alpha amylase. The best docking results obtained with 2b were −10.2, −9.4, −7.5, and −7.0 with human aldose reductase, monoglycerol lipase, GLP-1, and alpha amylase, respectively. 2c also gave a best docking score of −7.8 with human aldose reductase; however, poor scores were obtained with other three targets. Compound 2e was found to be best against aldose reductase with a docking score 7.7, which is comparatively less than the best compounds, 2a and 2b. Molecules 2d and 2f showed poor docking scores with all four targets. Overall, in the case of antidiabetic properties, 2a showed the highest docking score with the receptor human aldose reductase. Compounds 2a–2f were evaluated against various ADME criteria, including LogS, Lipinski’s Rule of five, LogP, BBB and polar surface area (TPSA) permeability, and gastrointestinal absorption. Compounds that met Lipinski’s Rule of five and had higher gastric absorption were chosen for additional analysis; further compounds with low or medium risk or no toxicity were also selected for additional analysis. The ADME and physicochemical properties of the titled compounds are summarized in Table 2. Compound 2a was selected as the final hit compound for additional study. The three-dimensional amino acid interactions of compound 2a with the aldose reductase receptor are illustrated in Figure 7. The binding mode of compound 2a was further validated by superimposing it with the co-crystallized ligand at the active site of aldose reductase, as shown in Figure 8.

Table 2.

ADME/physicochemical properties of titled compounds.

Figure 7.

3D amino acid interactions of 2a with the aldose reductase receptor.

Figure 8.

Superimposed picture of compound 2a with the co-crystallized ligand of the aldose reductase receptor at its active site.

4. Conclusions

The research focused on designing, synthesizing, and in silico screening thiadiazole–isatin derivatives. After a literature review, compounds were designed and evaluated using molecular docking, ADME prediction, and physicochemical analysis. The synthesis involved preparing thiadiazole intermediates followed by coupling with isatin. Docking studies of six compounds (2a–2f) showed that 2a and 2b passed Lipinski’s rule and exhibited good binding affinity, especially with human aldose reductase and monoglyceride lipase. Compound 2a gave the best docking results and better drug-likeness compared to 2b, while others showed lower activity. Overall, compounds 2a and 2b emerged as promising lead molecules for multi-enzyme targeting agents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S.; methodology, M.; software, N.S.; validation, N.S.; formal analysis, N.S.; investigation, M.; resources, N.S.; data curation, P.; writing—original draft preparation, P.; writing—review and editing, N.S.; visualization, M.; supervision, N.S.; project administration, N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding and primary author is thankful to K. N. Modi, Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, for providing necessary facilities for the completion of this research work. IIT Delhi is also acknowledged for providing the IR and NMR instrumentation facilities for characterization of compounds.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TLC | Thin layer Chromatography |

| TPSA | Total polar surface area |

| LogP | lipophilicity |

| LogS | Water solubility |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| GAA | Glacial Acetic Acid |

| CDCl3 | Deuterated Chloroform |

| TMS | Trimethylsilyl |

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| KOH | Potassium hydroxide |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Kabir, E.; Uzzaman, M. A review on biological and medicinal impact of heterocyclic compounds. Results Chem. 2022, 4, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, S.; Alhazza, M.I.; Ibrahim, A.A. A review on heterocyclic moieties and their applications. Catal. Sustain. Energy 2016, 2, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Nanda, A.K. A Review on Heterocyclic: Synthesis and Their Application in Medicinal Chemistry of Imidazole Moiety. Sci. J. Chem. 2018, 6, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arella, S.; Thanyasri, P.; Bhavana, P.; Reddy, M.S. Review on Bioactive Heterocyclic Compounds. EPRA Int. J. Res. Dev. (IJRD) 2023, 8, 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Neama, R.; Aljamali, N.M.; Jari, M. Synthesis, Identification of Heterocyclic Compounds and Study of Biological Activity. Asian J. Res. Chem. 2014, 7, 664–676. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319493644 (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Sharma, P.K.; Amin, A.; Kumar, M. A Review: Medicinally Important Nitrogen Sulphur Containing Heterocycles. Open Med. Chem. J. 2020, 14, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, D.M.; Safir, N.H.; Sodani, I.J.; Saalih, T.Y.; Al-sammarraie, H.K.; Khudair, M. History, Classification and Biological activity of Heterocyclic Compounds. Int. J. Nat. Hum. Sci. 2023, 4, 72–80. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373392090 (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Dawood, K.M.; Farghaly, T.A. Farghaly, Thiadiazole inhibitors: A patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2017, 27, 477–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Li, C.-Y.; Wang, X.-M.; Yang, Y.-H.; Zhu, H.-L. 1,3,4-Thiadiazole: Synthesis, Reactions, and Applications in Medicinal, Agricultural, and Materials Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5572–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhruzhinina, T.V.; Kondrashova, N.N.; Shvekhgeimer, M.G.A. Synthesis of new derivatives of polycapromide graft copolymers containing 2-(4-Aminophenyl)Quinoline-4-carboxylic acid fragments. Fibre Chem. 2004, 36, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.R.; Kumar, S.; Afzal, O.; Shalmali, N.; Ali, W.; Sharma, M.; Bawa, S. 2-Benzamido-4-methylthiazole-5-carboxylic Acid Derivatives as Potential Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors and Free Radical Scavengers. Arch. Pharm. Chem. Life Sci. 2017, 350, e1600313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).