Abstract

The selectivity of photosensitizers for light activation is a key advantage in photodynamic therapy (PDT), allowing for precise targeting while sparing healthy cells. Boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY)derivatives have emerged as promising PDT candidates due to their tunable photophysical properties and versatile synthesis. Herein, we explore the photophysical characterization and the in vitro photodynamic activity of BODIPY analogues meso-substituted with an anthracene moiety and functionalized with iodine atoms or formyl group at the 2,6-position. The formylated anthracene–BODIPY derivative exhibited the highest phototoxicity in 4T1 breast cancer cells, making it a potential candidate for a PDT photosensitizer.

1. Introduction

Photosensitizers are light-activated compounds that play a crucial role in the field of photodynamic therapy (PDT), an emerging non-invasive therapeutic modality for the treatment of various diseases, including cancer. PDT combines light and photosensitizers, which, in the presence of oxygen, generate cytotoxic reactive oxygen species and induce cellular death. In fact, PDT relies on the ability of photosensitizers to be selectively activated by light, allowing a precise local treatment, while minimizing collateral damage to healthy cells and tissues [1]. Moreover, studies have demonstrated that PDT is able to trigger the immune system and enhance the anti-tumor immunity [2,3,4].

Amongst the well-known photosensitizers (e.g., porphyrins, chlorin, xanthene, and ruthenium-based complexes), BODIPY derivatives have shown promising potential because of their highly tunable photophysical properties and versatile synthetic accessibility. Several studies have explored the optimization of the BODIPY core to improve singlet-to-triplet intersystem crossing and efficiency to generate singlet oxygen (singlet oxygen quantum yields) [5,6,7]. For example, the halogen substitution at the BODIPY core significantly impacts their photophysical properties by reducing their fluorescence quantum yields while enhancing intersystem crossing to the triplet state, and has been shown to improve singlet oxygen sensitization for BODIPY derivatives [8]. Similarly, complexing BODIPYs with metals such as Ir(III) can transform a photoinactive dye into an efficient triplet sensitizer, suggesting that these derivatives may act as effective PDT photosensitizers [9,10]. Moreover, the potential of BODIPY derivatives as singlet oxygen sensitizers extends beyond cancer treatment to the photodynamic inactivation of microbes, fungi, and viruses [11].

As an extension of the work developed in our research group [12,13], we report the design and evaluation of BODIPY derivatives functionalized with an anthracene moiety at meso and an iodine or formyl group at the 2,6-positions of the core. The photophysical characterization of the derivatives and in vitro PDT studies in cancer cells (the 4T1 cell line) were performed, to determine their potential as PDT photosensitizers.

2. Methods and Materials

A nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum was obtained on a Bruker Avance III 400 at an operating frequency of 400 MHz for 1H, using the solvent peak as internal reference. The solvents are indicated in parenthesis before the chemical shift values (δ relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS)). Mass spectrometry analysis was performed at the “C.A.C.T.I.-Unidad de Espectrometria de Masas” at the University of Vigo, Spain. All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Acros, and Fluka, and were used as received. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) analysis was carried out on 0.25 mm thick precoated silica plates (Merck Fertigplatten Kieselgel 60F254) and the spots were visualized under UV light. Chromatography on silica gel was carried out on Merck Kieselgel (230–400 mesh). The syntheses of BODIPY derivatives 1, 3, and 4 have been already published by our research group [13].

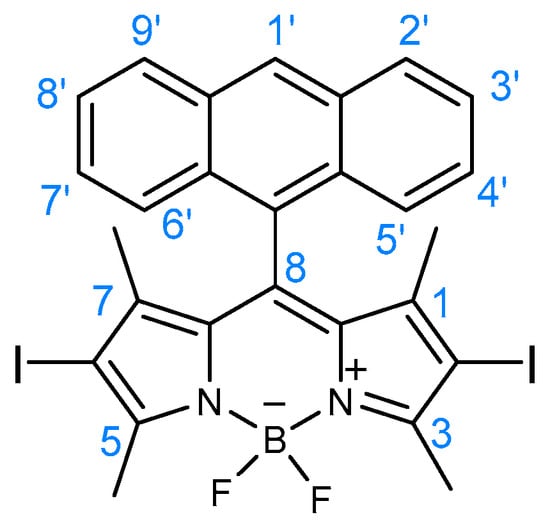

2.1. Synthesis of BODIPY Derivative 2

N-iodosuccinimide (NIS, 0.57 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (DCM, 6 mL) and added to a solution of BODIPY 1 (0.12 mmol) in DCM (6 mL). The reaction was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The solvent was evaporated under low-pressure conditions. The crude product was resuspended in ethyl ether (15 mL) and the solid was filtered under vacuum (0.042 g, η = 57%), giving the pure compound 2 (Figure 1), as a red solid.

Figure 1.

Structure of BODIPY derivative 2.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 0.68 (s, 6H, CH3-1 and CH3-7), 2.72 (s, 6H, CH3-3 and CH3-5), 7.45 (dt, J = 1.2 and 8 Hz, 2H, H-3′ and H-8′), 7.52 (dt, J = 1.2 and 8 Hz, 2H, H-4′ and H-7′), 7.83 (dd, J = 0.8 and 8 Hz, 2H, H-2′ and H-9′), 8.07 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, H-5′ and H-6′), 8.64 (s, 1H, H-1′) ppm.

MS (ESI) m/z (%): 678 ([M + 2]+•, 8), 677 ([M + 1]+•, 28), 676 ([M]+•, 7), 550 (100), 469 (50), 453 (46), 447 (80), 381 (35), 381 (35), 359 (38), 227 (33), 226 (30), 149 (45); HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + 1]+• calcd for C27H22BF2I2N2, 676.9928; found 676.9910.

2.2. Photophysical Characterization

The photophysical characterization of BODIPY derivatives was performed in tetrahydrofuran (THF) and toluene solutions. Absorption and fluorescence emission spectra were collected in a Shimadzy UV-2600i and Horiba-Jobin-Yvon FL322 spectrometer, respectively. The fluorescence quantum yields and singlet oxygen photosensitization quantum yields were obtained as previously reported [13].

2.3. Cell Culture and In Vitro Assays

Murine mammary carcinoma cell line from a BALB/cfC3H mouse (4T1 cells) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% of penicillin–streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were plated and passaged according to American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) recommendations and were used for the experiments while in the exponential growth phase.

The stock solutions of the BODIPY derivatives 1, 2 and 3 were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (10 mM) and the final DMSO percentage in each well was adjusted to be less than 1%.

2.3.1. Cellular Uptake Assay

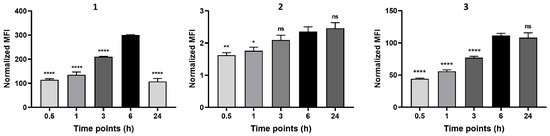

4T1 cells (40,000 cells/well) were seeded in 24-well plates in a final volume of 1 mL of DMEM and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Then, cells were incubated with the BODIPY derivatives at a concentration of 2.5 μM. After different incubation times (0.5, 1, 3, 6, and 24 h), the cells were washed and detached with 250 μL of trypsin, transferred to a 96-well U-shaped plate, and centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in 200 μL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution and the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a Novocyte 3000 cytometer (ACEA) with 488 nm laser excitation and filter 530/30. Data are presented as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) normalized to the mean fluorescence of untreated cells. This experiment was performed in duplicate and repeated in two sets of tests. Statistical analysis of results was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to study the statistical significance of the incubation times related to 6 h of incubation, and significance levels were established at p < 0.05.

2.3.2. Dark Toxicity and Phototoxicity of the BODIPY Derivatives

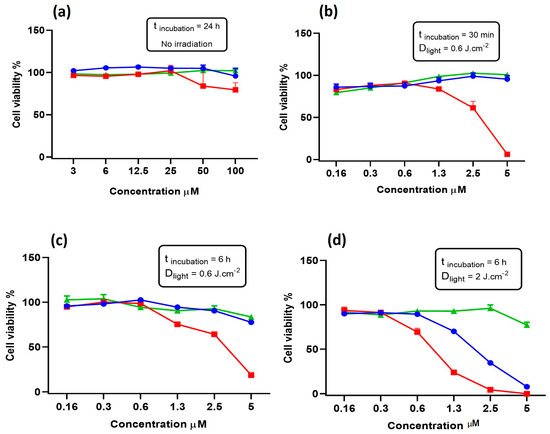

4T1 cells (6000 cells/well) were plated in 96-well plates and kept in incubation for 24 h to allow the attachment of the cells. Cells were then treated with the BODIPY derivatives in a concentration range from 0 to 100 µM. After 24 h, cell viability (dark toxicity) was determined by the Resazurin assay.

Phototoxicity was evaluated in parallel experiments using two sets of light doses (0.6 J·cm−2 and 2 J·cm−2) and two sets of incubation times (30 min and 6 h). Cells were treated with the BODIPY derivatives in a concentration range from 0.16 to 5 μM and, after each incubation time, the cells were washed with PBS, and 200 μL of Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) cell culture medium without Phenol Red was added. Controls, namely the untreated cells, were included on every plate. The cells were then irradiated with a green LED light source (505 nm). A correction factor from the overlap of the absorption spectra between the laser and each compound was calculated and applied to achieve an accurate light dose [14]. After irradiation, cells were washed and fresh DMEM was added. The cell viability was determined by the Resazurin assay 24 h post-illumination. Both studies were performed in triplicates and repeated in two sets of tests. Statistical analysis of results was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Photophysical Characterization of the BODIPY Derivatives

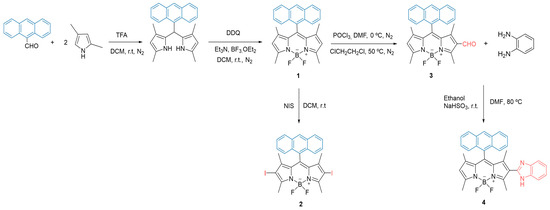

Scheme 1 shows the synthetic route to obtain the derivatives bearing an anthracene group at meso position and different functionalization at position 2 and/or 6 of the BODIPY core. The syntheses of BODIPY derivatives 1, 3, and 4 have been recently reported by our research group [13]. We employed the well-known Lindsey’s method (BODIPY precursor 1), followed by the halogenation reaction using N-iodosuccinimide (NIS) to obtain the BODIPY derivative 2, functionalized with iodine at positions 2 and 6.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the BODIPY derivatives 1–4.

3.2. Photophysical Characterization

A comprehensive photophysical evaluation of the BODIPY derivatives was performed, to investigate the effects of the substituent groups on the photophysical properties, including the singlet oxygen generation efficiency (Table 1). Compared to BODIPY precursor 1, the heavy atom effect of the iodine atoms in BODIPY 2 and the electron-withdrawing behavior of the formyl group in BODIPY 3 promoted a significant reduction in the fluorescence quantum yield and a concomitant increase in the triplet formation quantum yield (estimated from the efficient singlet oxygen sensitization quantum yield). The introduction of the benzimidazole heterocycle (BODIPY 4) in the position 2 of the BODIPY core significantly decreased the singlet oxygen sensitization quantum yield value (ɸΔ = 0.04 vs. 0.27, 0.76, and 0.74 for compounds 1, 2, and 3 in tetrahydrofuran solution, respectively), which may ultimately impair the compound’s in vitro photosensitization efficacy.

Table 1.

Photophysical data (including absorption, λabs, fluorescence emission maxima, λfluo, fluorescence quantum yields, ɸF, and singlet oxygen sensitization quantum yields, ɸΔ) for BODIPY derivatives 1–4, in toluene (a) and tetrahydrofuran solution (b) at 293 K.

3.3. In Vitro Assays

Considering the photophysical data obtained regarding the singlet oxygen quantum yields (ɸΔ), the BODIPY derivatives 1, 2, and 3 were investigated in 4T1 breast cancer cells.

Initially, the cellular uptake was investigated through flow cytometry, as depicted in Figure 2, which demonstrated that compounds 1 and 3 are rapidly internalized by the cells, reaching a maximum at 6 h of incubation. In contrast, the fluorescence detected in the cells treated with BODIPY 2 was significantly lower, which might be due to its lower ɸF. However, we cannot exclude that the lower solubility of compound 2 in aqueous medium may have affected its ability to diffuse through the cell membrane.

Figure 2.

Cellular uptake of the BODIPY derivatives 1, 2, and 3 in 4T1 cells. Cell uptake was monitored by flow cytometry after 0.5, 1, 3, 6, and 24 h of incubation with 2.5 μM of each compound. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 2). Statistical differences versus 6 h incubation: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001.

The cell viability was evaluated in the dark after 24 h of incubation with the compounds, and no cytotoxicity was observed, even at the highest concentration tested (Figure 3a). In contrast, irradiation with a light dose of 0.6 J·cm−2 after 30 min of incubation with compound 3 resulted in cell death with concentrations above 2.5 μM (IC50 = 2.92 μM), whilst compounds 1 and 2 did not affect cell viability, even at the highest concentration tested (Figure 3b). The experiment was repeated with an incubation time of 6 h; however, the results did not significantly differ from the previous study (Figure 3c). Therefore, since a higher incubation time did not increase the BODIPYs’ phototoxicity, a light dose of 2 J·cm−2 was applied. Under this condition, it was observed that not only did BODIPY 3 became more toxic at lower concentrations (IC50 = 0.88 μM), but also, compound 1 was capable of considerably decreasing cell viability (IC50 = 2.05 μM) (Figure 3d). Unexpectedly, any phototoxic effects of BODIPY derivative 2 were not observed, although the compound displayed the highest singlet oxygen quantum yield. This could be attributed to its low solubility in aqueous medium and/or poor cell uptake.

Figure 3.

Cell viability of 4T1 cells incubated with BODIPY derivatives 1 (blue), 2 (green), and 3 (red) for 24 h without irradiation (a); for 30 min and irradiated with 0.6 J·cm−2 (b); for 6 h and irradiated with 0.6 J·cm−2 (c); and for 6 h and irradiated with 2 J·cm−2 (d).

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, here we reported a series of BODIPY derivatives bearing an anthracene moiety at meso position and functionalized at position 2 and/or 6 with a formyl group or iodine atoms. The photophysical evaluation in toluene and THF solutions revealed that the derivatives substituted with the halogen atoms (BODIPY 2) and the electron-withdrawing formyl group (BODIPY 3) displayed the highest singlet oxygen photosensitization quantum yields. The in vitro assays demonstrated that BODIPY 1 and 3 were easily internalized, and the three compounds were non-toxic for 4T1 cancer cells in the dark. However, under irradiation with a light dose of 2 J·cm−2, compound 1 and 3 reduced cell viability by 50%, with only 2.05 and 0.88 μM, respectively. These results suggest the promising potential, especially of the formylated BODIPY derivative, as photosensitizers in anticancer PDT.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.M.R., J.P. and L.C.G.-d.-S.; methodology, R.C.R.G., M.M.M.R., J.P., L.C.G.-d.-S. and S.P.G.C.; validation, M.M.M.R., J.P., L.C.G.-d.-S. and S.P.G.C.; formal analysis, R.C.R.G., M.M.M.R., J.P., L.C.G.-d.-S. and S.P.G.C.; investigation, R.C.R.G. and S.C.S.P.; resources, M.M.M.R., J.P., L.C.G.-d.-S. and S.P.G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.R.G. and S.C.S.P.; writing—review and editing, R.C.R.G., M.M.M.R., J.P., L.C.G.-d.-S. and S.P.G.C.; supervision, M.M.M.R., J.P., L.C.G.-d.-S., and S.P.G.C.; project administration, M.M.M.R., J.P., L.C.G.-d.-S. and S.P.G.C.; funding acquisition, M.M.M.R., J.P., L.C.G.-d.-S. and S.P.G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) and FEDER (European Fund for Regional Development)-COMPETE-QRENEU, through the Chemistry Research Centre of the University of Minho (ref. CQ/UM (UID/QUI/00686/2020)), and the Coimbra Chemistry Centre (refs. UIDB/00313/2020 and UIDP/00313/2020), project PTDC/QUI-OUT/3143/2021 and a PhD grant of R.C.R. Gonçalves (SFRH/BD/05278/2020). The NMR spectrometer Bruker Avance III 400 is part of the National NMR Network and was purchased within the framework of the National Program for Scientific Re-equipment, contract REDE/1517/RMN/2005 with funds from POCI 2010 (FEDER) and FCT.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lan, M.; Zhao, S.; Liu, W.; Lee, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, P. Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1900132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, M.; Tanaka, M.; Kojima, Y.; Nishie, H.; Shimura, T.; Kubota, E.; Kataoka, H. Anti-Tumor Immunity Enhancement by Photodynamic Therapy with Talaporfin Sodium and Anti-Programmed Death 1 Antibody. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2023, 28, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reginato, E. Immune Response after Photodynamic Therapy Increases Anti-Cancer and Anti-Bacterial Effects. World J. Immunol. 2014, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Lobo, A.C.; Gomes-da-Silva, L.C.; Rodrigues-Santos, P.; Cabrita, A.; Santos-Rosa, M.; Arnaut, L.G. Immune Responses after Vascular Photodynamic Therapy with Redaporfin. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Montero, R.; Prieto-Castañeda, A.; Sola-Llano, R.; Agarrabeitia, A.R.; García-Fresnadillo, D.; López-Arbeloa, I.; Villanueva, A.; Ortiz, M.J.; De La Moya, S.; Martínez-Martínez, V. Exploring BODIPY Derivatives as Singlet Oxygen Photosensitizers for PDT. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malacarne, M.C.; Gariboldi, M.B.; Caruso, E. BODIPYs in PDT: A Journey through the Most Interesting Molecules Produced in the Last 10 Years. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gong, Q.; Wang, L.; Hao, E.; Jiao, L. The Main Strategies for Tuning BODIPY Fluorophores into Photosensitizers. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2020, 24, 603–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbe, M.; Costero, A.M.; Sancenón, F.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Ballesteros-Cillero, R.; Ochando, L.E.; Chulvi, K.; Gotor, R.; Gil, S. Halogen-Containing BODIPY Derivatives for Photodynamic Therapy. Dyes Pigm. 2019, 160, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, L.; Chiniforoshan, H. New Cyclometalated Ir (III) Complexes with NCN Pincer and Meso-Phenylcyanamide BODIPY Ligands as Efficient Photodynamic Therapy Agents. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 34160–34169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palao, E.; Sola-Llano, R.; Tabero, A.; Manzano, H.; Agarrabeitia, A.R.; Villanueva, A.; López-Arbeloa, I.; Martínez-Martínez, V.; Ortiz, M.J. AcetylacetonateBODIPY-Biscyclometalated Iridium(III) Complexes: Effective Strategy towards Smarter Fluorescent Photosensitizer Agents. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 10139–10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, B.; Situ, X.; Scholle, F.; Bartelmess, J.; Weare, W.; Ghiladi, R. Antiviral, Antifungal and Antibacterial Activities of a BODIPY-Based Photosensitizer. Molecules 2015, 20, 10604–10621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, R.C.R.; Pina, J.; Costa, S.P.G.; Raposo, M.M.M. Synthesis and Characterization of Aryl-Substituted BODIPY Dyes Displaying Distinct Solvatochromic Singlet Oxygen Photosensitization Efficiencies. Dyes Pigm. 2021, 196, 109784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.C.R.; Belmonte-Reche, E.; Pina, J.; Costa Da Silva, M.; Pinto, S.C.S.; Gallo, J.; Costa, S.P.G.; Raposo, M.M.M. Bioimaging of Lysosomes with a BODIPY pH-Dependent Fluorescent Probe. Molecules 2022, 27, 8065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaberle, F.A. Assessment of the Actual Light Dose in Photodynamic Therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2018, 23, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).