Abstract

Background: This work aimed to determine whether curcumin influences the development of type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM) in a murine model. Methodology: Four groups of six non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice (A, B, C, and D) and one CD1 control group (E) were included. Groups A, B, and C received different doses of turmeric curcumin (50 mg/kg body weight (bw), 100 mg/kg bw, and 200 mg/kg bw, respectively) for six weeks, while groups D and E received only the vehicle simultaneously. Glycemia, body weight, and inflammatory infiltrate in the pancreatic islets were determined in all cases. Also, insulin and vitamin D receptor (VDR) expression in pancreatic cells was evaluated relative to the basal expression in the control (group E). Results: Glycemia in all the animals treated with curcumin remained stable from weeks 1 to 6, while the control group showed hyperglycemia (≥500 mg/dL) and weight loss (16.7 g ± 1 g). Treated animals had less inflammatory infiltrate, while maintaining insulin and VDR expression in the pancreas, compared with the control group. Finally, the serum concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines in treated animals were statistically lower than in the control group without curcumin. Conclusions: Curcumin delays the onset of T1DM and reduces pancreatic inflammatory infiltrate.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a noninfectious chronic disease [1] and the leading cause of many health-related complications such as pathologies related to microcirculation, including coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, and microvascular complications such as end-stage renal disease, retinopathy, and neuropathy [2]; in addition to an increase in the risk of premature death, which is significantly influenced by socioeconomic factors (relative risk: 0–54 years (1.59 (confidence interval 1.24–2.04)) [3]. This disease is accompanied by chronic inflammation and oxidative stress [4,5].

Natural products, including medicinal plants, have traditionally been used to treat different health problems in humans and animals. According to the World Health Organization, 80% of the population in developing countries still depends on traditional or folk medicines to prevent or treat various conditions [6]. Traditional medicine derived from plant extracts has proven to be affordable and clinically effective in treating some diseases, and, through multiple analyses of their effects, it has been possible to verify the impact of some plants and rule out others [7]. Regarding DM, it has been described that some plant organisms act like insulin (e.g., Momordica charantia) [8], induce insulin secretion (e.g., Allium cepa, Allium sativum) [9], have bioactive compounds that regenerate beta-cells of the islets of the pancreas (e.g., Pterocarpus marsupium) [10], reduce glucose absorption at the intestinal level (e.g., Cyamposis tertragonoloba, Ocimum sanctum) [11], or have bioactive compounds with oxygen radical scavenging activity (e.g., Eugenia jambolana) [12]. Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by progressive degradation of pancreatic function due to the destruction of beta-cells [12]. Due to this background, plant organisms with anti-inflammatory potential could delay T1DM development.

Curcumin is a polyphenol found in turmeric (Curcuma longa) and is used as a spice, food coloring, and traditional herbal medicine [13]. Also, curcumin has health benefits such as antioxidant [14], anti-inflammatory [15], and anticancer properties [16], improvement of brain function [17], and control of obesity and DM [18].

1α, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25-(OH) 2D3), the active metabolite of vitamin D, is an essential element in the maintenance of mineral homeostasis and bone architecture [19] and has immunomodulatory effects mediated by its nuclear receptor (vitamin D Receptor (VDR)) [20], which has been found in a large variety of cells from different tissues like the skin, intestines, and kidneys [21]. The VDR contains two overlapping ligand binding sites, a genomic pocket and an alternative pocket (AP), that mediate the regulation of gene transcription and rapid responses, respectively. Flexible VDR ligand docking calculations predict that the major blood metabolite, 25(OH)-vitamin D3 (25D3), and curcumin (CM) bind more selectively to the VDR-AP when compared with the related metabolite secosteroid hormone 1α,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 (1,25D3) [22]. However, despite this knowledge, the possibility that administering plant-derived ligands, such as curcumin, may induce effects similar to those of 25D3 has not been fully explored.

The main objective of this work was to determine whether curcumin influences the development of T1DM in a murine model and whether this effect is related to its anti-inflammatory activity at three different oral doses. The protocol was performed in a murine model of T1DM, an autoimmune disease characterized by pancreatic infiltration of immune cells that leads to T cell-mediated destruction of insulin-producing beta cells. Non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice are an important and successful resource for studying T1DM; unlike many autoimmune disease models, the NOD mouse spontaneously develops the disease and shares many similarities with human T1DM [23].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. An Animal Model of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and the Experimental Design

The present study is an experimental, prospective, controlled, and randomized study. Twenty-four-week-old female mice and six CD1 mice of the same age and gender were purchased from Harlan Laboratory (Mexico City, Mexico). They were raised at the Unidad de Medicina Experimental, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), animal facility, in accordance with the National Guidelines for Animal Care. Four groups of six NOD mice (Groups A, B, C, and D) and a control group of six CD1 mice (Group E) were included in the study.

This study was previously approved by the local Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, National Autonomous University of Mexico (research project number: 105-2014). Animals were housed in acrylic cages, with six mice per cage. The recommended living space for all animals was always respected, e.g., it was kept at 97 cm2 for animals weighing more than 25 g. Environmental conditions were maintained in accordance with NOM-062-ZOO-1999, “Technical specifications for the production, use, and care of laboratory animals,” so that the animals were kept in rooms with a temperature range of 20–22 °C, a humidity of 55%, and a 12/12 h light/dark cycle. Food and water were offered ad libitum during the entire experiment. After six weeks of treatment, all the animals in each group were euthanized by an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (200 mg/kg bw) administered intraperitoneally (IP). Blood was collected by cardiac puncture. After coagulation, the serum was separated by centrifugation and frozen at −80 °C until use, and finally, the pancreas was removed for histopathological analysis.

2.2. Curcumin Treatment

To explore whether curcumin altered the development of T1DM, we administered the compound in olive oil, as turmeric curcumin (C1386, Sigma-Aldrich™, St. Louis, MO, USA) had previously been reported to be dose-dependent [24]. We selected three increasing doses previously shown to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in mouse models and tested them in the first three groups of mice [25]. Curcumin was administered daily for 6 weeks as follows: Group A 50 mg/kg body weight (bw) [24], Group B 100 mg/kg bw [26], and Group C 200 mg/kg bw [27].

The mixture was prepared before each administration and administered by intragastric gavage, introducing the substance directly into the stomach with precise doses and consistent timing. At each timepoint, any signs of discomfort in the animals were evaluated. Group D (NOD mice) and Group E (CD1 mice) were maintained as controls, receiving only oral administration of the vehicle, which was olive oil. These turmeric curcumin doses were chosen because they fell within the range reported to have anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects. Treatment with curcumin or vehicle, and monitoring of blood glucose levels, began at 24 weeks of age, a time at which hyperglycemia begins in this T1DM model [28].

2.3. Glucose Levels

Fasting blood glucose levels were measured weekly for six weeks in all groups of mice by puncturing the caudal vein, which had previously been disinfected, with the blood glucose monitoring system Accu-Check Active® (F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland), in which approximately 20 µL of whole blood was placed. Hyperglycemia was defined by fasting blood glucose levels above 120 mg/dL.

2.4. Histopathological Analysis of Mice Pancreas

Histological analysis of inflammation in NOD mice from each group was performed at the end of the experiment. The pancreas samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde buffered with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and embedded in a medium containing purified paraffin and plastic polymers with regulated molecular weights, with a melting point of 56 °C, enriched with Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Cuttings of 2 and 3 μm thickness were made with each sample. The first cuts were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) to characterize the inflammatory infiltrate surrounding pancreatic islets. This procedure was performed blindly by a specialist histopathologist.

Insulitis degree was assessed using the following scale, ranging from 0 to 4: 0 normal islets with no sign of inflammatory cell infiltration; 1 peri-islet inflammatory cell infiltration; 2 more extensive peri-islet infiltration, but with less than one-half of the islet area occupied; 3 extensive intra-islet inflammation involving more than half of the islet area, and 4 completely infiltrated by inflammatory cells. At least 25 islets were scored for each animal [29].

2.5. Vitamin D Receptor and Insulin Expression by Immunostaining

Immunostaining was performed on 3 μm thick sections to explore VDR expression in the pancreas of the mice. Immunostaining was performed using the biotin-free protein detection system EPOS/HRP (Enhanced Polymer One Step/Horseradish Peroxidase) for epitope unmasking. Epitope Retrieval Solution 10× concentrate, pH 6 (Novocastra Leica Biosystems, Newcastle Ltd., Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK) was used. The samples were treated with 0.9% hydrogen peroxide in an aqueous medium for 5 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. The sample was incubated for 45 min with the polyclonal antibody anti-VDR (Abcam™-ab3508, Cambridge, UK) dilution 1:50. For insulin detection, a different sample was incubated with the rabbit monoclonal anti-insulin antibody, clone EP125 (Bio SB™, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) at a final dilution of 1:50. The samples were incubated with the anti-rabbit antibody of the Detection System: polymer/peroxidase BondTM (Polymer Refine Detection) for 10 min each (Leica Biosystems Newcastle Ltd., Newcastle upon Tyn, UK). To visualize the reaction, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine-H2O2 was used as substrate (Biocare Medical, Pacheco, CA, USA). The reaction was monitored under a microscope. The counterstain was made with Gill’s hematoxylin and adjusted with ammonium hydroxide solution at 0.37 M.

2.6. Quantification of Cytokines

After 6 weeks, circulating cytokines in the serum were quantified through ELISA. We determined the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, Interferon (IFN)-γ, Interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-10 (all from Peprotech™, Cranbury, NJ, USA). All procedures were conducted following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The capture antibody was diluted to 100 mg/mL in PBS, and 100 μL per well was added to an ELISA plate (Nunc MaxiSorp™, Ridgefield, NJ, USA), which was incubated overnight at room temperature. Subsequently, the wells were washed with 300 μL of washing solution (0.05% Tween 20 in PBS) per well. Next, 300 μL of blocking solution (1% BSA in PBS) was added. Next, 100 μL of standard or serum sample was added to each well in duplicate and incubated at room temperature for 2 h, and then the plate was washed three times. The detection antibody was diluted to 0.25 mg/mL and 100 μL was added to each well, then incubated at room temperature for 2 h. After the time had elapsed, the plate was rewashed three times. Streptavidin–HRP was diluted to 0.025 μg/mL and 100 μL was added to each well. The plate was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the plate was washed three times. Then, 100 μL of the substrate solution was added to each well, and the wells were incubated in the dark for 20 min. The colorimetric reaction was quantified in an ELISA plate; we read it at 450 nm with a wavelength correction of 620 nm. Finally, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, cytokine concentrations were determined by comparing them with a 7-point standard curve.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are described with frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables with mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median ± interquartile range (IQR), depending on the distribution of the variables. To compare serum glucose levels across weeks and body weights at week 6, a Kruskal–Wallis test was used to evaluate whether there was a difference among populations. The differences between groups were analyzed with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. If a difference was found, comparisons between groups were performed using Bonferroni correction. All analyses were two-sided; α was set at 5% unless otherwise specified. Stata v. 14.2 was used to perform all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Three Different Doses of Curcumin Delay Serum Glucose Elevation in Non-Obese Diabetic Mice

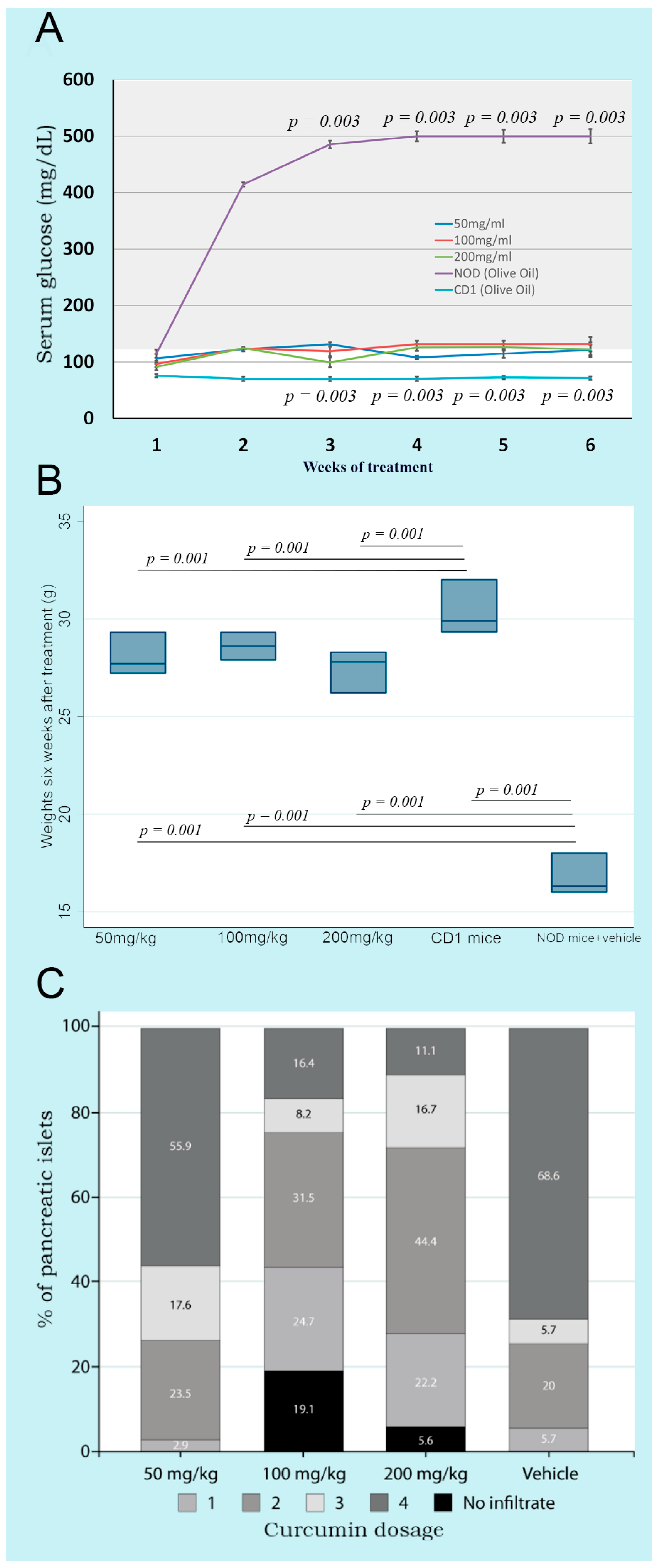

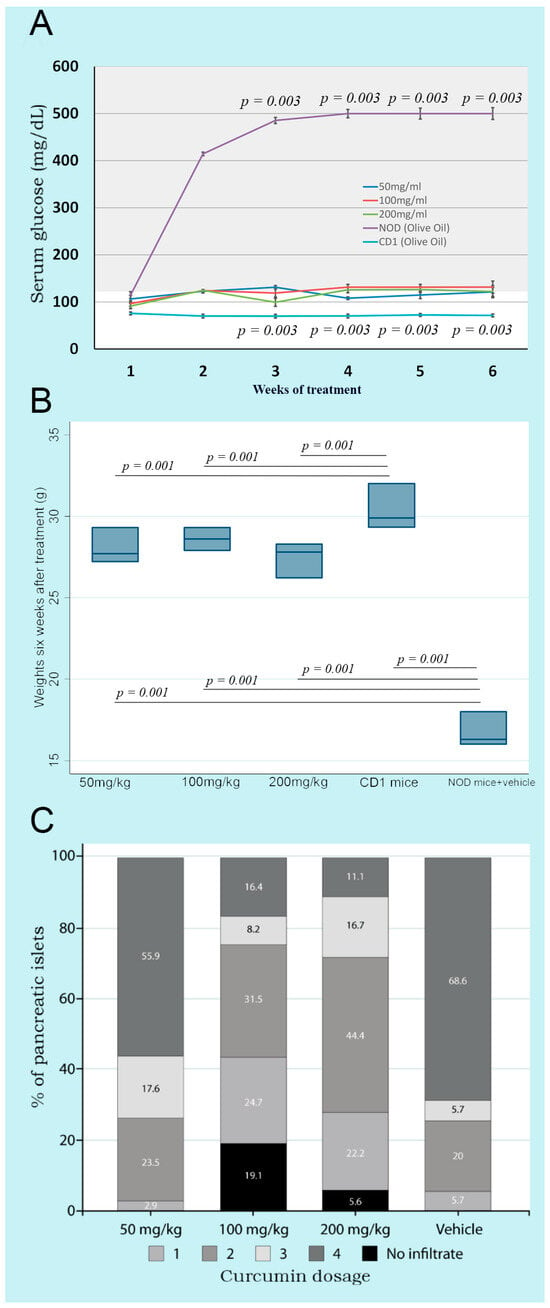

Oral administration of three doses of curcumin (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg bw) showed that glycemia remained stable from weeks 1 to 6, without significant differences between groups. However, the NOD control group treated only with the vehicle, from weeks 1 to 6, presented significantly higher glucose levels than the three treated groups. CD1 mice showed significantly lower serum glucose levels than NOD mice, which developed the autoimmune phenomenon that induces diabetes (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Kinetics of glycemia, weights, and insulitis in non-obese diabetic mice treated with three different doses of curcumin administered orally. (A) shows the kinetics of glycemia throughout the experimental process. The gray area shows hyperglycemia. NOD mice with olive oil and CD1 mice without any treatment are shown as controls; (B) shows the weight of the mice after six weeks of treatment. NOD mice with olive oil and CD1 mice without any treatment are shown as controls; (C) shows the insulitis in the pancreas determined at the end of the experimental process.

3.2. Curcumin Treatment Prevents Weight Loss in Non-Obese Diabetic Mice

The body weight of the curcumin-treated mice was significantly greater than that of the control group of NOD mice without curcumin after six weeks. On the other hand, CD1 mice (an ancestor of the NOD strain) showed significantly higher weights compared to all NOD mice. This finding indicated that curcumin treatment in any of the three doses prevented the weight loss accompanying the characteristic hyperglycemia in T1DM (Figure 1B).

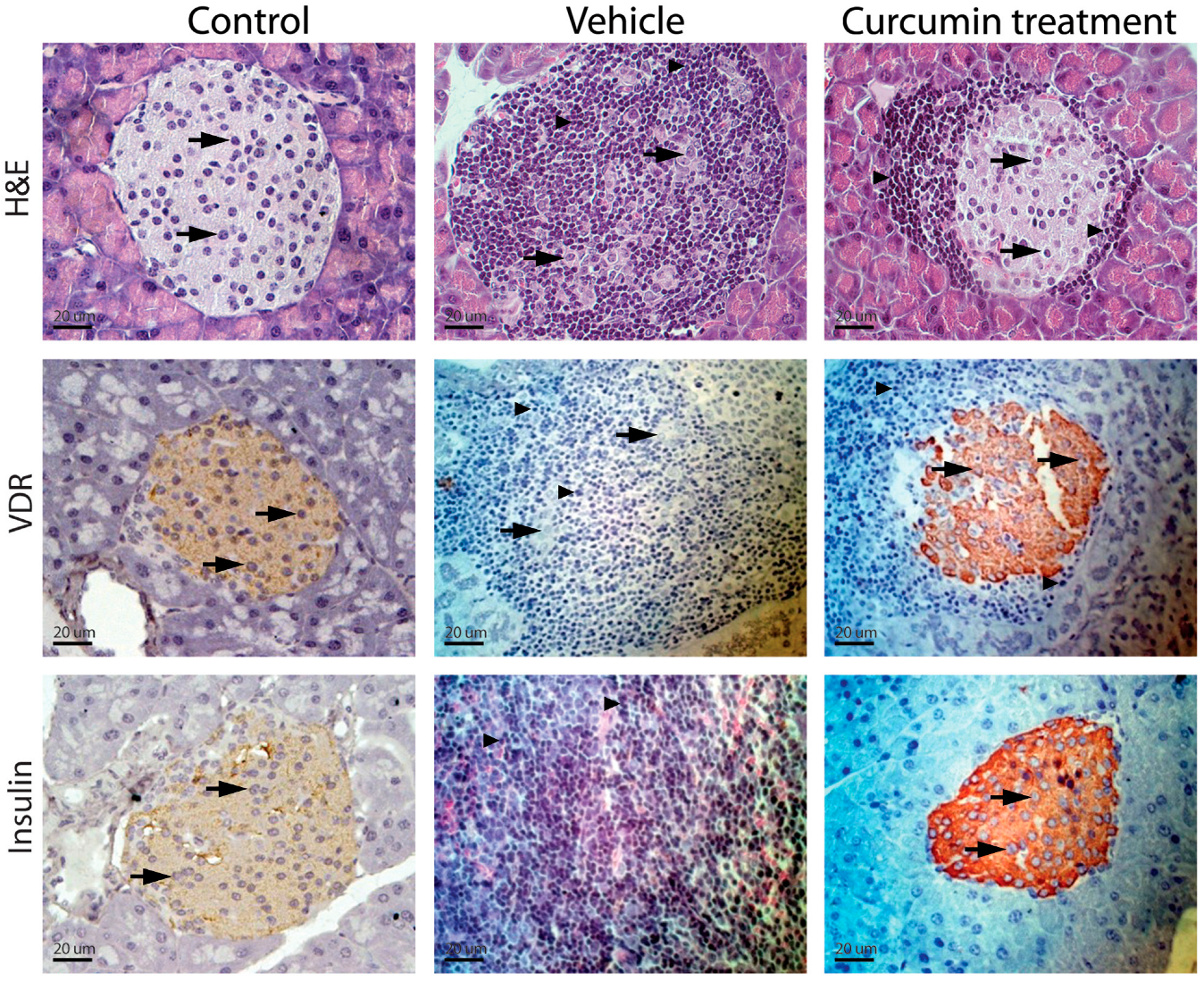

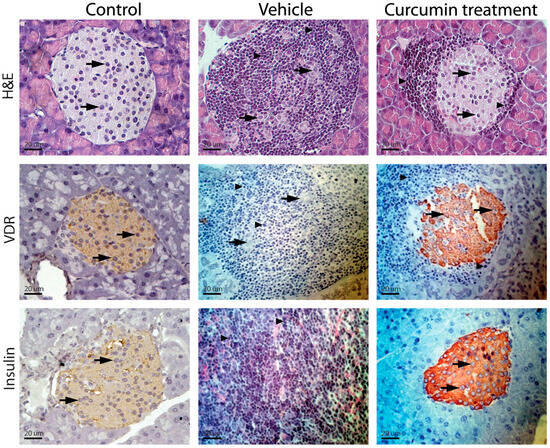

3.3. Curcumin Treatment Decreases the Inflammatory Infiltrate in the Pancreas of Non-Obese Diabetic Mice

Control NOD mice (group D) presented compact parenchyma with marked atrophy of the pancreatic islets. The islets showed chronic lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate and extensive lymphocyte aggregates between islets and ducts. Lymphocytes were monomorphic and uniform, although larger cells resembling centroblasts were occasionally observed. The inflammatory infiltrate dissected the acini. NOD mice treated with different doses of curcumin (groups A–C) presented a pancreas with compact acini, partial atrophy, and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate, with variable intensity and clusters of lymphocytes in the peripancreatic fat. Control CD1 mice (group E) showed no apparent changes in cellular architecture (Figure 2). The degree of insulitis showed agreement with the histological observations. The mice treated only with the vehicle (group D) had more destroyed islets, with a score of 4. In contrast, the animals treated with different doses of curcumin presented islets with a lower degree of insulitis (Figure 1C). The groups treated with higher doses of curcumin (100 and 200 mg/kg bw) presented islets without inflammatory infiltrates, with a score close to 0, only with residual inflammation.

Figure 2.

Inflammatory infiltrate intensity and insulin and vitamin D receptor expression. Control NOD mice (group D) presented compact parenchyma with marked atrophy of the pancreatic islets. The islets showed chronic lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (arrowheads) and extensive lymphocyte aggregates between islets and ducts. Lymphocytes were monomorphic and uniform, although larger cells resembling centroblasts were occasionally observed. The inflammatory infiltrate dissected the acini (thick arrows). NOD mice treated with different doses of curcumin (groups A–C) showed a pancreas with compact acini, partial atrophy, and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate of variable intensity (thin arrows), as well as clusters of lymphocytes in the peripancreatic fat. Control CD1 mice (group E) showed no apparent changes in cellular architecture (Figure 2). The images shown correspond to animals treated with 50 mg/kg; however, the findings reflect what was observed across the three doses.

3.4. Vitamin D Receptor and Insulin Expression in Pancreatic Islets Characterize Curcumin Treatment

The possible anti-inflammatory effect of curcumin treatment may result from its interaction with VDR. However, this T1DM model is characterized by intense inflammatory infiltration and pancreatic cell destruction, leading to reduced expression of multiple signaling proteins. With all this in mind, we determined whether VDR expression continued in pancreatic cells, which was the first requirement for a probable interaction with curcumin.

Immunostaining of the pancreas in mice showed that, in preserved pancreatic islet cells in groups A, B, and C (Figure 2), the VDR expression and insulin were maintained despite being surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate. However, in group D, due to extensive infiltration of inflammatory cells and tissue destruction, it was impossible to detect expression of either molecule (Figure 2).

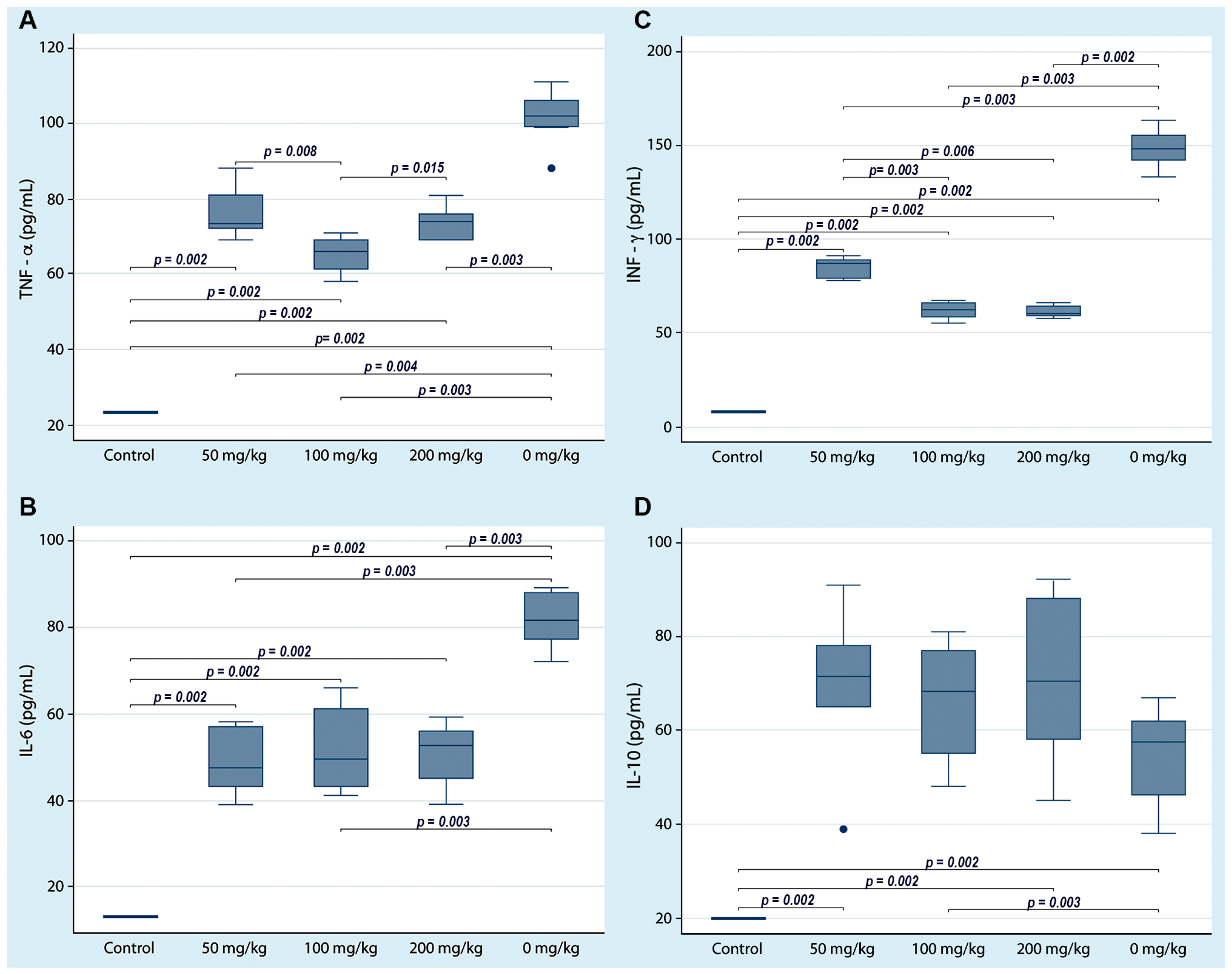

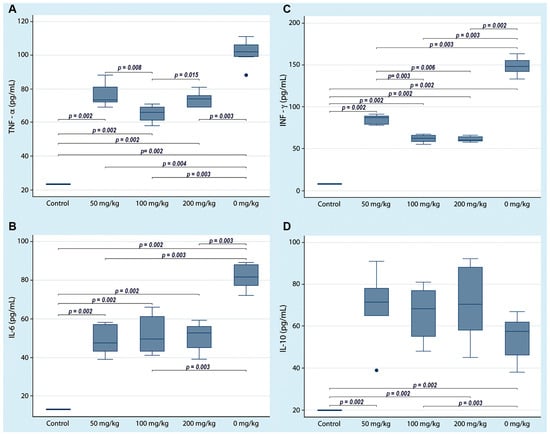

3.5. The Three Doses of Curcumin Applied Decrease Proinflammatory Cytokines

To assess the immune status of NOD mice treated with three curcumin doses, ELISA was performed to quantify the serum concentrations of four cytokines. The serum concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, INF-γ, and IL-6) were significantly variable; however, it is notable that the serum concentrations in the NOD mice (group D) that received only the vehicle were statistically higher than those in the mice that received the different curcumin doses (groups A–C). Otherwise, the serum concentration of IL-10 was significantly lower in the animals that did not receive curcumin compared to the other three groups of animals that received curcumin (Figure 3). The centrality and dispersion indicators for each cytokine are shown in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Serum cytokine concentrations in non-obese diabetic mice with three doses of curcumin administered orally. Cytokines were quantified by ELISA at the end of the experiment. Each box shows a particular cytokine (A) TNF-α, (B) IL-6, (C) INF-γ and (D) IL-10. The lines indicate significant differences with the corresponding p-value. All control group determinations were below the limit of detection for each cytokine.

Table 1.

Quantification of proinflammatory cytokines in the three doses of curcumin and the control group.

4. Discussion

In this work, we have shown that animals treated with three different doses of curcumin had normal serum glucose levels during treatment compared to the hyperglycemia observed in the control group at the same time; furthermore, this effect was characterized by increased expression of insulin and VDR in pancreatic islets.

The findings in this report are consistent with a remarkable anti-inflammatory effect previously reported for three different curcumin doses [24,26,30]. A lower quantity of inflammatory infiltrate in the pancreas is associated with a delay in the development of hyperglycemia in animals treated with curcumin. This anti-inflammatory effect could enable beta cells in the pancreas to survive for longer.

In this work, we confirm the beneficial effect of curcumin on the development of T1DM [31]; previously, Seo et al. reported that administering curcumin to genetically modified diabetic mice was associated with reduced insulin resistance and less weight loss, which are fundamental aspects of the management of this degenerative disease [31]. Our data showed a significant anti-inflammatory effect of the curcumin treatment in NOD mice, a model of T1DM with an autoimmune origin [27].

Castro et al. reported that curcumin administration at three doses delays the onset of hyperglycemia in an accelerated model of T1DM. The authors described defects in T lymphocyte proliferation and a failure to produce gamma interferon [27]. Also, the authors showed that, as was the case in this work, the three doses tested induce the same effect on T1DM development. However, at the end of the treatment, we observed high variability in serum glucose concentrations, weight throughout the protocol, and serum cytokine concentrations across the three doses. In addition, groups treated with higher doses of curcumin presented islets without inflammatory infiltrates, with a score near 0. These observations highlight the benefits of curcumin treatment, which reduce inflammatory infiltration, preserve pancreatic islet architecture, and result in less weight loss and better blood glucose control.

Treatment with curcumin has demonstrated its potential as an anti-inflammatory agent in different experimental models [32]; here, we observed a significant effect in the reduction of IL-6, INF-γ, and TNF-α. This agrees with the results reported by Phumsuay et al., who carried out a protocol in which, in a carrageenan-induced mouse paw edema model, a lowering of IL-6 and TNF-α was observed, in addition to inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2) at three different doses; these findings were similar to those reported here, secondary to the inhibition of Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activity [33]. Regarding IL-10, an essential cytokine for regulating the inflammatory response, a phenomenon opposite to the previous cytokines was observed, since serum levels were significantly higher than those observed in NOD mice that received only the vehicle and CD1 mice used as negative controls. The choice of this strain was made because it is a genetic line that has been used as a genetic background to obtain the mouse NOD [34]; the use of this control aimed to show the histological structures without pathological alterations derived from the development of diabetes. This finding coincides with what was reported by Chai et al. in an acute lung injury mouse model, where, after applying treatment with curcumin, the researchers observed an increase in the activity of regulatory T lymphocytes, evaluated by the release of IL-10, in addition to a change in macrophage polarization, which transitioned from an M1 to an M2 phenotype, where tissue repair is favored [35]. Changes in proinflammatory cytokine levels (particularly IL-17, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-6) in T1DM patients highlight their significance as indicators of pathogenesis and as promoters of complications and problems associated with autoimmune T1DM [36]. The anti-inflammatory effect was statistically significant under these treatment conditions, as reflected by lower serum cytokine concentrations in animals treated with three different doses. However, this was highly heterogeneous and not dose-dependent; this coincides with the observations of Garcea et al., who administered three different doses of curcumin to patients with colorectal cancer. They found a lower amount of adducts in the DNA of all patients in a non-dose-dependent manner; the authors argued that this phenomenon could be related to the absorption system, which is saturable [37], and that the heterogeneity of the effect was probably influenced by the stage of the disease being treated and the composition of the microbioma [38].

VDR has been reported to stimulate a second messenger system, including phospholipase C, protein kinases C, phosphatases, and G protein receptors, which induces increased calcium influx and glucose influx into β-cells, ultimately resulting in insulin secretion [39]. On the other hand, it has been documented that VDR has two ligand-binding sites, the genomic pocket and the alternative pocket, with the former having a stronger and exclusive affinity for vitamin D3, the more active form. However, it has also been documented that the alternative pocket is more flexible, allowing it to bind not only vitamin D3, but also other ligands of different chemical natures, forming a tetramer with the retinoid receptor [22]. Indeed, Menegaz et al. demonstrated that curcumin can bind to the alternative pocket of VDR, and its binding can elicit biological responses similar to those of its preferred ligand, vitamin D3 [22]. Genetic regulation is performed by the VDR (linked to its ligand) RXR tetramer. Haussler et al. show that curcumin is a slightly more efficient lipophilic ligand when it comes to inducing transcriptional regulation through VDR activity; although the mechanism by which curcumin acts has not been fully described, these authors hypothesize that this slight advantage could explain the immunomodulatory effects, because in this same work it is described that the regulation can be stimulatory or repressive depending on the sequence of the target genes [40]. Delayed pancreatic degradation due to a direct or indirect effect of curcumin treatment could maintain VDR expression and, in turn, affect the immune system in various ways. This possibility should be explored in future studies.

Proximate analysis of turmeric reveals that the herb contains 6–13% moisture, with 60–70% carbohydrate, 6–8% protein, 5–10% fat, 3–7% minerals (potassium, sodium, calcium, iron, phosphorus), and trace amounts of vitamins. Essential oils obtained by steam distillation represent 3–7% of the turmeric rhizome and mainly consist of terpenoids, including sesquiterpenoids, monoterpenoids, and norsesquiterpenoids. There are also 3–5% curcuminoids, which comprise more than 50 structurally related compounds, the three principal ones being curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin [41]. This natural compound has demonstrated numerous beneficial effects in managing various degenerative diseases; however, like other herbal extracts, it presents some challenges with regard to its administration and dosage. In herbal extracts, the biological effect is difficult to attribute to a single compound; combining the different components apparently enhances its activity. Due to the presence of phenolic compounds, absorption is one of the main challenges that needs to be overcome prior to therapeutic administration [42]. In this work, we demonstrate that the previously documented anti-inflammatory effect could represent an alternative in autoimmune pathologies such as T1DM; however, curcumin has low aqueous solubility and is rapidly metabolized in the digestive system, which limits its potential use [43]. Nevertheless, demonstrating relevant biological effects opens up the possibility studies that seek alternatives to improve this problem, such as those in which better options for the administration of curcumin are explored, because this polyphenolic compound shows good tolerance and biosecurity, even at high doses, but is associated with poor bioavailability, rapid metabolism, and very rapid systemic elimination. Anand et al. demonstrated that bioavailability could be substantially improved with the use of glucuronidation, liposomes, nanoparticles and complexes with phospholipids [44]. On the other hand, Ataei et al. demonstrated higher bioavailability with the use of nanofibers [45]; unfortunately, the acquisition of curcumin with the adjuvants mentioned above is not common.

The present work has significant limitations. We accept that the number of animals considered in each group is one of them; however, the NOD strain of mice is a widely accepted model of T1DM, and because it is based on the use of an inbred strain with a high degree of similarity, the results obtained are highly reproducible. The results do not include naive controls to demonstrate the appearance of the pancreas without inflammatory alterations, because all NOD mice develop this autoimmune phenomenon; however, the histological appearance of the pancreas in CD1 mice, the origin strain of NOD mice, is shown. Finally, the quantified cytokines showed remarkable dispersion, as shown in the Supplementary Material that accompanies this article. To account for this, relevant statistical tests were selected for the data. However, the report on the anti-inflammatory effect of T1DM opens the door to new studies exploring this topic. Finally, vitamin D levels were not quantified in serum because the methodology in this work focused on verifying the effects of an alternative VDR ligand in this case, curcumin.

5. Conclusions

Previous studies have shown that curcumin can bind the alternative pocket of VDR, and our results confirm that curcumin treatment delays pancreatic degeneration and hyperglycemia in a murine model of T1DM. Furthermore, histological analysis of the pancreases of animals treated with curcumin showed VDR expression despite the inflammatory damage. All these results, taken together, indicate that oral administration of curcumin induces an anti-inflammatory effect that protects the pancreas and maintains its function in a murine model of T1DM.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diabetology7020031/s1: Table S1: Serum glucose during the six weeks of treatment with curcumin (mg/dL); Table S2: Weight of animals after 6 weeks of treatment with curcumin (g); Table S3: Insulinitis after six weeks of treatment with curcumin; Table S4: Serum concentration of proinflammatory cytokines (pg/mL).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R.-M., R.F.-V. and G.P.-R.; Methodology, F.J.G.-V., A.P.H.-A. and G.A.-U.; Formal Analysis, J.R.-S. and E.R.-M.; Investigation, A.C.-K.; Writing—Review and Editing, E.R.-M., R.F.-V. and G.P.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was previously approved by the local Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, National Autonomous University of Mexico (research project number: 105-2014, 4 November 2014). Animals were housed in acrylic cages, with six mice per cage. Environmental conditions were maintained in accordance with NOM-062-ZOO-1999, “Technical specifications for the production, use, and care of laboratory animals”.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the raw data produced in this work are included as Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marco Gudiño Zayas, Sandra Paola Chávez Jurado, and Valeria Yolid Herrera Juárez for providing technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schmidt, A.M. Highlighting Diabetes Mellitus: The Epidemic Continues. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, J.L.; Pavkov, M.E.; Magliano, D.J.; Shaw, J.E.; Gregg, E.W. Global trends in diabetes complications: A review of current evidence. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, J.A.; López-Pineda, A.; Orozco-Beltrán, D.; Carratalá-Munuera, C.; Barber-Vallés, X.; Gil-Guillén, V.F.; Nouni-García, R.; Soliva, Á.C. Diabetes mellitus as a cause of premature death in small areas of Spain by socioeconomic level from 2016 to 2020: A multiple-cause approach. Prim. Care Diabetes 2024, 18, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsholme, P.; Cruzat, V.F.; Keane, K.N.; Carlessi, R.; de Bittencourt, P.I., Jr. Molecular mechanisms of ROS production and oxidative stress in diabetes. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 4527–4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lontchi-Yimagou, E.; Sobngwi, E.; Matsha, T.E.; Kengne, A.P. Diabetes mellitus and inflammation. Curr. Diab Rep. 2013, 13, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilburt, J.C.; Kaptchuk, T.J. Herbal medicine research and global health: An ethical analysis. Bull. World Health Organ. 2008, 86, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, N.; Pham, B.; Le, L. Bioactive Compounds in Anti-Diabetic Plants: From Herbal Medicine to Modern Drug Discovery. Biology 2020, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandawate, P.R.; Subramaniam, D.; Padhye, S.B.; Anant, S. Bitter melon: A panacea for inflammation and cancer. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2016, 14, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, K.; Mathew, B.C.; Augusti, K.T. Antidiabetic and hypolipidemic effects of S-methyl cysteine sulfoxide isolated from Allium cepa Linn. Indian. J. Biochem. Biophys. 1995, 32, 49–54. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7665195 (accessed on 28 May 2025). [PubMed]

- Dhanabal, S.P.; Kokate, C.K.; Ramanathan, M.; Kumar, E.P.; Suresh, B. Hypoglycaemic activity of Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb. Phytother. Res. 2006, 20, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, G.R.; Vanlalhruaia, P.; Stalin, A.; Irudayaraj, S.S.; Ignacimuthu, S.; Paulraj, M.G. Polyphenols-rich Cyamopsis tetragonoloba (L.) Taub. beans show hypoglycemic and beta-cells protective effects in type 2 diabetic rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 66, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, A.; Varghese, A.; Kachwala, Y.; Bhaskar, M.; Laddha, A.; Jamal, A.; Yadav, P. Eugenia jambolana extract reduces the systemic exposure of Sitagliptin and improves conditions associated with diabetes: A pharmacokinetic and a pharmacodynamic herb-drug interaction study. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2019, 9, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, T. Curcumin as a functional food-derived factor: Degradation products, metabolites, bioactivity, and future perspectives. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, S.; Haylett, W.L.; Johnson, G.; Carr, J.A.; Bardien, S. Antioxidant effects of curcumin in models of neurodegeneration, aging, oxidative and nitrosative stress: A review. Neuroscience 2019, 406, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadati, S.; Sadeghi, A.; Mansour, A.; Yari, Z.; Poustchi, H.; Hedayati, M.; Hatami, B.; Hekmatdoost, A. Curcumin and inflammation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized, placebo controlled clinical trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 19, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, N.S.; Srivastava, R.A.K. Curcumin and quercetin synergistically inhibit cancer cell proliferation in multiple cancer cells and modulate Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and apoptotic pathways in A375 cells. Phytomedicine 2019, 52, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluta, R.; Ulamek-Koziol, M.; Czuczwar, S.J. Neuroprotective and Neurological/Cognitive Enhancement Effects of Curcumin after Brain Ischemia Injury with Alzheimer’s Disease Phenotype. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T.; Song, Z.; Weng, J.; Fantus, I.G. Curcumin and other dietary polyphenols: Potential mechanisms of metabolic actions and therapy for diabetes and obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 314, E201–E205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacher, T.D.; Fischer, P.R.; Pettifor, J.M. Vitamin D treatment in calcium-deficiency rickets: A randomised controlled trial. Arch. Dis. Child. 2014, 99, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, S.; Na, S.; Rathnachalam, R. Noncalcemic actions of vitamin D receptor ligands. Endocr. Rev. 2005, 26, 662–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; DeLuca, H.F. Where is the vitamin D receptor? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 523, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menegaz, D.; Mizwicki, M.T.; Barrientos-Duran, A.; Chen, N.; Henry, H.L.; Norman, A.W. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) regulation of voltage-gated chloride channels by ligands preferring a VDR-alternative pocket (VDR-AP). Mol. Endocrinol. 2011, 25, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.A.; Wong, F.S.; Wen, L. The importance of the Non Obese Diabetic (NOD) mouse model in autoimmune diabetes. J. Autoimmun. 2016, 66, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoncini-Silva, C.; Fassini, P.G.; Carlos, D.; de Paula, N.A.; Ramalho, L.N.Z.; Giuliani, M.R.; Pereira, Í.S.; Guimarães, J.B.; Suen, V.M.M. The Dose-Dependent Effect of Curcumin Supplementation on Inflammatory Response and Gut Microbiota Profile in High-Fat Fed C57BL/6 Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, e2300378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Dai, C.; Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Qiu, J. Curcumin Attenuates on Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Acute Liver Injury in Mice via Modulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 and TGF-beta1/Smad3 Pathway. Molecules 2018, 23, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Q.; Lv, X.D.; Liu, G.F.; Gu, G.L.; Chen, R.Y.; Chen, L.; Fan, J.H.; Wang, H.Q.; Liang, Z.L.; Jin, H.; et al. Curcumin improves experimentally induced colitis in mice by regulating follicular helper T cells and follicular regulatory T cells by inhibiting interleukin-21. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 72, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, C.N.; Tabarrozzi, A.E.B.; Winnewisser, J.; Gimeno, M.L.; Noguerol, M.A.; Liberman, A.C.; A Paz, D.; A Dewey, R.; Perone, M.J. Curcumin ameliorates autoimmune diabetes. Evidence in accelerated murine models of type 1 diabetes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014, 177, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Thayer, T.C.; Wen, L.; Wong, F.S. Mouse Models of Autoimmune Diabetes: The Nonobese Diabetic (NOD) Mouse. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2128, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Yue, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jin, Y. Oral Administration of Silkworm-Produced GAD65 and Insulin Bi-Autoantigens against Type 1 Diabetes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.W.; Cha, J.Y.; Jung, J.E.; Chang, B.C.; Kwon, H.J.; Lee, B.R.; Kim, D.Y. Curcumin attenuates allergic airway inflammation and hyper-responsiveness in mice through NF-kappaB inhibition. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 136, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.; Choi, M.; Jung, U.J.; Kim, H.; Yeo, J.; Jeon, S.; Lee, M. Effect of curcumin supplementation on blood glucose, plasma insulin, and glucose homeostasis related enzyme activities in diabetic db/db mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008, 52, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Ao, M.; Dong, B.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, L.; Chen, Z.; Hu, C.; Xu, R. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Curcumin in the Inflammatory Diseases: Status, Limitations and Countermeasures. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 4503–4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phumsuay, R.; Muangnoi, C.; Wasana, P.W.D.; Hasriadi; Vajragupta, O.; Rojsitthisak, P.; Towiwat, P. Molecular Insight into the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of the Curcumin Ester Prodrug Curcumin Diglutaric Acid In Vitro and In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampudia, R.M.; Alba, A.; Planas, R.; Pujol-Autonell, I.; Mora, C.; Verdaguer, J.; Vives-Pi, M. PCR-based microsatellite analysis to accelerate diabetogenic genetic background acquisition in transgenic mice. Inmunología 2011, 30, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.S.; Chen, Y.Q.; Lin, S.H.; Xie, K.; Wang, C.J.; Yang, Y.Z.; Xu, F. Curcumin regulates the differentiation of naive CD4+T cells and activates IL-10 immune modulation against acute lung injury in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 125, 109946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari Khataylou, Y.; Ahmadiafshar, S.; Rezaei, R.; Parsamanesh, S.; Hosseini, G. Curcumin Ameliorate Diabetes type 1 Complications through Decreasing Pro-inflammatory Cytokines in C57BL/6 Mice. Iran. J. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 19, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcea, G.; Berry, D.P.; Jones, D.J.L.; Singh, R.; Dennison, A.R.; Farmer, P.B.; Sharma, R.A.; Steward, W.P.; Gescher, A.J. Consumption of the putative chemopreventive agent curcumin by cancer patients: Assessment of curcumin levels in the colorectum and their pharmacodynamic consequences. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005, 14, 120–125. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15668484 (accessed on 28 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gomes, T.L.N.; Zenha, R.S.S.; Antunes, A.H.; Faria, F.R.; Rezende, K.R.; de Souza, E.L.; Mota, J.F. Evaluation of the Impact of Different Doses of Curcuma longa L. on Antioxidant Capacity: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Crossover Pilot Trial. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 3532864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizwicki, M.T.; Norman, A.W. The vitamin D sterol-vitamin D receptor ensemble model offers unique insights into both genomic and rapid-response signaling. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2, re4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haussler, M.R.; A Haussler, C.; Bartik, L.; Whitfield, G.K.; Hsieh, J.C.; Slater, S.; Jurutka, P.W. Vitamin D receptor: Molecular signaling and actions of nutritional ligands in disease prevention. Nutr. Rev. 2008, 66, S98–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; El Rayess, Y.; Rizk, A.A.; Sadaka, C.; Zgheib, R.; Zam, W.; Sestito, S.; Rapposelli, S.; Neffe-Skocińska, K.; Zielińska, D.; et al. Turmeric and Its Major Compound Curcumin on Health: Bioactive Effects and Safety Profiles for Food, Pharmaceutical, Biotechnological and Medicinal Applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 01021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlatshwayo, S.; Thembane, N.; Krishna, S.B.N.; Gqaleni, N.; Ngcobo, M. Extraction and Processing of Bioactive Phytoconstituents from Widely Used South African Medicinal Plants for the Preparation of Effective Traditional Herbal Medicine Products: A Narrative Review. Plants 2025, 14, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucevic Popovic, V.; Karahmet Farhat, E.; Banjari, I.; Jelicic Kadic, A.; Puljak, L. Bioavailability of Oral Curcumin in Systematic Reviews: A Methodological Study. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Newman, R.A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Bioavailability of curcumin: Problems and promises. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataei, M.; Roufogalis, B.D.; Majeed, M.; Shah, M.A.; Sahebkar, A. Curcumin Nanofibers: A Novel Approach to Enhance the Anticancer Potential and Bioavailability of Curcuminoids. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023, 30, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.