Abstract

Introduction: Advancements in diabetes technology have transformed diabetes management, yet technology implementation remains inconsistent due to barriers at both the clinician and patient levels. Team-based collaborative care offers a promising strategy to bridge these gaps. Framework: The Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM), which incorporates the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance (RE-AIM) framework, was applied to identify clinician and patient-level barriers to technology implementation and guide development of team-based strategies for improvement. Application of this framework is illustrated through a rural primary care clinic implementing a remote patient monitoring program. Results: Analysis across RE-AIM domains identified team-based, interprofessional strategies for enhancing technology implementation and sustainability. Recommended strategies include structured onboarding and digital literacy support for both patients and clinicians, clear delineation of team roles and intentional integration of workflows, continuous quality improvement through feedback and huddles, and sustained organizational and policy support that ensures security, reimbursement, and equitable access. Conclusions: Application of the PRISM framework to improve diabetes technology implementation allows for translation of technological innovation into meaningful outcomes.

1. Introduction

Diabetes technology has advanced rapidly in the last decade, resulting in a transformation of patient care. In particular, devices such as continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and automated insulin delivery (AID) systems have revolutionized diabetes management, and are recommended by the American Diabetes Association for many patients. Consistent CGM use has lowered A1c in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with type 1 patients experiencing lower rates of hypoglycemia. Improvements in type 2 patients tend to occur even without medication or insulin dose changes [1]. AID systems combine an insulin pump, CGM, and a smart algorithm that automatically adjusts insulin delivery based on glucose patterns. These systems reduce A1c and hypoglycemia while also decreasing diabetes-related stress and improving sleep [2]. Beyond these devices, innovations such as smart insulin pens [3], digital health platforms, mobile health applications, and clinical decision support software (CDSS) have also shown promise in enhancing diabetes care [4,5]. Likewise, broader digital tools including telemonitoring [6], telehealth visits [7], and online patient portals [8] may expand access to care and improve outcomes. Studies show that app-based and digital diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES) produce outcomes that are comparable to or better than usual care [9]. More recently, advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have opened the door for technology to take on entirely new roles—screening for complications, predicting disease progression, automatically optimizing insulin delivery, and streamlining documentation in the medical record [10]. Emerging patient-facing AI tools, including those that support dietary management or count carbohydrates from photographs, may further improve glycemic outcomes and patient engagement [10,11].

Despite these advancements, use of diabetes technology remains uneven. In US youths with type 1 diabetes, CGM use increased from 4% in 2011 to 82% in 2023, and in adults with type 1 it rose from 5% to 57% over the same time period [12]. Yet uptake in type 2 diabetes has been far slower, with only 13% of patients with type 2 diabetes having used a CGM in a 2021 study [13]. Utilization rates are even lower for smart insulin pens, likely due to limited evidence on their efficacy and cost-effectiveness [14]. Broad app use (CGM apps, dietary apps) is more common, though concentrated among younger, more educated, and higher-income patients [15]. Even when digital platforms are available, only about half of individuals eligible for DSMES through their insurance actually receive it [9]. AI adoption and implementation are also in their early stages, with applications such as diabetic retinopathy screening and AI-driven CDSS still emerging in practice, though AI is increasingly embedded in consumer-facing products such as smart devices and mobile health applications [10]. While use is increasing, the benefits of these technologies are not yet fully realized and equitably applied across patient populations.

One strategy to bridge implementation gaps and enhance the impact of technology is team-based collaborative care. Team-based care has been consistently associated with improved diabetes outcomes, including reductions in HbA1c, enhanced efficiency, reduced burnout, and better patient-reported outcomes [16,17,18,19]. When integrated with healthcare technology and DSMES, interprofessional models can further enhance engagement and clinical effectiveness [4,9]. However, realizing these benefits requires overcoming persistent barriers that may occur at the system, clinician, and patient levels.

In this essay, we focus on clinician- and patient-level barriers to the adoption, implementation, and maintenance of diabetes technology and propose strategies to address them. We argue that team-based collaborative care is essential for translating technological innovation into real-world improvements in outcomes. Without deliberate approaches to implementation, these advancements may fail to achieve their full potential and may even risk widening disparities.

2. Framework

To guide this essay, we apply the integrated Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) framework, which includes the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework [20]. RE-AIM is commonly used to plan, evaluate, and report on interventions across its five domains. In parallel, PRISM accounts for contextual factors that shape implementation, such as organizational characteristics, stakeholder perspectives, and the external environment. (Conceptual figures of PRISM are available at https://re-aim.org/resources-and-tools/figures-and-tables/ [accessed on 26 November 2025]). Together, these integrated frameworks capture both intervention outcomes (RE-AIM) and the contextual factors that determine whether adoption efforts succeed in practice (PRISM). This integrated model was chosen for its emphasis on practicality and sustainability, with the goal of connecting implementation context with measurable outcomes in real-world clinical settings. We used an inductive approach to framework mapping. Through this implementation lens, we examine how interprofessional teams can systematically overcome barriers, integrate technology into routine care, and ultimately enhance both clinical outcomes and quality of life for individuals with diabetes.

Contextual factors that may influence diabetes technology implementation are organized using the PRISM framework. Table 1 outlines considerations at both the organization/clinician and patient levels, including perceptions of the technology, available resources, external influences like coverage and regulation, and the infrastructure needed to support long-term use. A positive response to the questions in Table 1 indicates that the factor may be a facilitator whereas a negative response may indicate a barrier to implementation. These factors provide important background for understanding the conditions that make implementation more or less successful [21]. Building from this foundation, our discussion is structured using the RE-AIM framework, looking at how each domain can be leveraged by interprofessional teams to improve outcomes [22].

Table 1.

PRISM Factors Influencing Diabetes Technology Implementation at the Organization/Clinician and Patient Levels.

To demonstrate how this can work in practice, we include a case scenario of a rural primary care clinic implementing remote patient monitoring.

Case Scenario

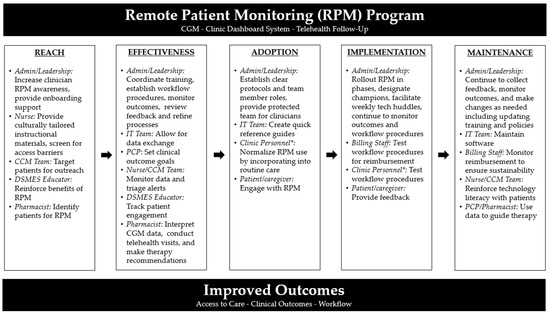

A rural primary care clinic has decided to implement a remote patient monitoring (RPM) program using CGM, a clinic dashboard system, and telehealth follow-ups to make frequent medication adjustments in real time based on CGM data. The goal is to increase access to diabetes care, improve glycemic outcomes, and leverage technology to improve clinic workflows. Figure 1 provides a visual for enhancing RE-AIM outcomes with this case scenario.

Figure 1.

Recommendations for Enhancing RE-AIM Outcomes in Case Scenario Example. Abbreviations: Admin = administration; CCM = chronic care management; CGM = continuous glucose monitor; DSMES = diabetes self-management and support; IT = information technology; PCP = primary care provider; RPM = remote patient monitoring. * Clinic personnel may include PCP, nurse, CCM team member, DSMES educator, pharmacist, or others.

3. Discussion

3.1. Reach

In the context of diabetes technology adoption, reach determines whether the intended patients and clinicians are aware of, have access to, and feel able to engage with new tools. Reaching the target population can be done by using established and effective communication systems to spread awareness of the available technology and its benefits. Identifying potential drivers and motivators of use will be helpful in selecting those benefits that should be promoted. Initial information sharing is important, but onboarding must also be user-friendly. Step-by-step digital literacy education, tailored training, and direct sign-up opportunities help patients engage early and build confidence. Such training opportunities need to be offered at multiple touchpoints, especially in the early phases, and will also allow for barriers to use to be identified and addressed.

It is also important to acknowledge and address structural barriers to healthcare technology access. This may include supporting policies that expand broadband infrastructure and affordable internet access, or working with technology developers to create inclusive, accessible tools. Patients can be screened to determine if they are at risk for digital exclusion (e.g., rural populations, older adults, patients without internet). Promotional and educational materials should also be provided in multilingual and culturally competent ways.

Case Scenario: Enhancing Reach

To ensure RPM is offered to appropriate patients, the clinic can use patient portal announcements and targeted telephone outreach from the Chronic Care Management (CCM) team. Administration can develop culturally tailored and multi-lingual instructional materials that nurses can provide during diabetes management visits, along with screening for access barriers. DSMES educators can reinforce the value of the RPM program in their sessions and offer direct enrollment. Pharmacists can identify eligible patients based on medication use or glycemic control patterns. Offering step-by-step onboarding support, including device and app set-up, to patients and caregivers will also promote early engagement. In addition, leadership can build awareness among clinicians through demonstration sessions and presentation of evidence demonstrating clinical and workflow benefits.

3.2. Effectiveness

Effectiveness in this context reflects whether the intervention produces meaningful improvements in clinical outcomes, patient/clinician experience, and care delivery, while minimizing unintended negative outcomes. Enhancing program effectiveness begins with using evidence-based tools and resources, and learning from similar implementation efforts when possible. Programs will be more effective if there are sufficient resources for implementation, including the availability of tools or processes that allow for seamless integration into the current workflow and everyday use. Clinicians require training and leadership support, and patients require the confidence and resources to engage with new tools. Workflows for securing insurance coverage and billing for relevant clinical services should be developed where applicable.

Effectiveness should be tracked and measured, including both process outcomes and clinical endpoints. Using interdisciplinary teams is necessary to identify clinically relevant metrics. Gathering and using feedback from others can increase effectiveness and help identify additional training and development opportunities.

Case Scenario: Enhancing Effectiveness

Integration of data is important, and the clinic’s information technology (IT) team can build a data exchange that directly integrates with their electronic medical record (EMR) to display data in the patient’s chart [23]. As primary care providers set clinical outcome goals, clinical pharmacists can interpret incoming CGM data and use regular telehealth visits to make timely therapy recommendations. Nurses and the CCM team can monitor and triage alerts and provide support when needed. DSMES educators can track engagement with the technology and adapt materials accordingly. Administrators coordinate clinician training sessions to standardize use of the platform, establish workflows for billing and insurance coverage, and monitor outcomes such as glycemic control, emergency visits, and patient satisfaction. Leadership uses these data for ongoing feedback and to refine processes over time.

3.3. Adoption

Adoption reflects the extent to which clinicians, staff, and patients choose to use a technology and integrate it into their care or practice. Encouraging adoption can be supported through a team-based approach that assigns clear roles. For example, nurses providing education on patient portals and onboarding support, pharmacists interpreting remote monitoring data, primary care providers reinforcing technology use as a standard part of care, and IT staff ensuring that troubleshooting is efficient. Team members who have a comprehensive understanding of their role may have increased buy-in to sustain new technology. The development of team protocols for onboarding, troubleshooting, and integrating digital tools and platforms (e.g., third-party CGM platforms, telehealth platforms, CDSS tools) can increase consistency and confidence. Simulation-based training can also provide hands-on experiences and an opportunity to troubleshoot common challenges to allow for sustained use of technology. For patients, leveraging family and caregivers as digital health allies can strengthen patient adoption and engagement through supports like integrating companion apps and patient portals into care plans.

Case Scenario: Enhancing Adoption

Successful adoption depends on building confidence in the technologies and commitment among staff, clinicians, and patients. The clinic can achieve this by establishing clear protocols and delineating team roles to ensure consistency and accountability. Staff and clinicians should be involved early in protocol development to ensure buy-in and that procedures will align with existing workflows. Nurses, providers, and pharmacists can be given demonstrations and protected time to practice with the platform before launch, and the IT team can provide quick-reference guides to support troubleshooting. Simulation-based sessions allow the team to address common challenges and improve confidence before implementation. For patient buy-in, clinical staff and DSMES educators can normalize RPM by incorporating it into standard diabetes care and education. Patients and caregivers can also be engaged as active partners through shared data access by the routine offering of CGM companion apps and patient portal engagement.

3.4. Implementation

The implementation domain in this setting examines how consistently and effectively a new technology is integrated into routine practice. Successful implementation requires engagement of diverse stakeholders in program design, including clinical and nonclinical staff, patients, and caregivers. During the implementation phase, target workflow optimization by integrating technology review huddles to gather feedback, refine use cases, talk through barriers, and prevent workflow disruption. Ensuring easy access to resources and personnel is also beneficial. While fidelity to the planned rollout is important, so is flexibility and adaptability. In many situations, alternative solutions may need to be used. Ongoing evaluation during this phase is also critical to inform refinements and support a seamless transition to the maintenance phase, which emphasizes long-term sustainability.

Case Scenario: Enhancing Implementation

The clinic can begin with a phased rollout, piloting RPM in a small group of patients identified by the CCM and pharmacy teams. Leadership can designate physician, nurse, pharmacist, and IT champions to help guide the initial process, supported by administrative, billing, and IT staff. Weekly technology huddles are helpful to bring together all team members to review barriers, refine workflows, identify technical challenges, and share patient and staff feedback. Billing staff can develop and test workflows for reimbursement for RPM clinical services including identification of relevant codes and reporting requirements. Similarly, clinical staff can develop workflows for securing insurance coverage, including a prior authorization protocol for CGMs. Patient and caregiver feedback should be actively and frequently solicited from those involved in the pilot using surveys and other feedback tools distributed through the patient portal. Administrators should monitor clinic workflow and identify disruptions. Flexibility is emphasized during the rollout process, actively encouraging adaptation to challenges and testing of alternative solutions when appropriate.

3.5. Maintenance

The maintenance domain reflects the ability to sustain technology use over time at both the patient and organizational levels. Sustaining new programs involves continued education and training, consistent metric tracking, and adaptation to an ever-evolving healthcare landscape. Clinicians and staff benefit from incorporating technology literacy into continuing education, professional curricula, and institution-specific training. Patients and communities benefit from health technology literacy embedded into DSMES and community health initiatives

Continued monitoring may include tracking previous metrics as well as creating new ones. With more technology use, additional data will be available so evaluations and comparisons can be made pre/post new technology use. Lastly, institutional adoption and maintenance may require updating and creating new and transparent policies and procedures.

Case Scenario: Enhancing Maintenance

Sustaining the RPM program will require continued training, education, evaluation, and adaptation. Nurses and the CCM team should reinforce technology literacy at routine patient visits and continue to screen for access and utilization barriers. Providers and pharmacists can use long-term CGM trends to guide therapy and ensure equitable access through proactive insurance documentation and advocacy for coverage expansion. Administrators can continue to monitor metrics such as glycemic control, patient satisfaction, and technology engagement to inform program refinements over time. The team can work to update training, protocols, and policies annually to reflect new payer requirements and regulatory changes. To sustain the program, billing staff can also monitor reimbursement for RPM and services, updating billing practices and payer documentation as requirements change to ensure financial viability. IT staff should maintain platform compatibility, security, and troubleshooting steps for technical issues. Billing staff monitor reimbursement trends and adjust documentation practices to sustain financial viability. Lastly, it is important to continually collect feedback (e.g., through portal surveys and DSMES visit follow-ups).

3.6. Additional Considerations

When planning for the implementation of new technology, there are additional considerations of note. Healthcare professionals may face a learning curve during the initial technology adoption phase, including increased time demands and workflow adjustments. It may be tempting to rely on the “tech-savvy” and the “early adopters” on the team, but an interdisciplinary approach is critical in order to distribute responsibility, enhance team efficiency, prevent burnout, and improve continuity of care. Effective implementation requires teamwork and awareness of each technology’s limitations. Teams should identify challenges, share feedback, refine workflows, and uphold ethical standards. Tools like CDSS may assist in care by making suggestions and identifying gaps, but human oversight remains essential in order to appropriately contextualize and apply AI-driven insights. Biases in algorithms caused by the underrepresentation of certain populations in training datasets may result in inequitable care or even misdiagnosis by CDSS. For example, underrepresentation of racial minorities in healthcare datasets has been linked to less accurate diagnostic tools for these groups [24]. AI tools that utilize black-box systems whose internal operations are not transparent can also hinder healthcare providers’ ability to assess the accuracy or appropriateness of AI-generated recommendations, raising concerns about accountability [25]. The healthcare team must be comfortable and confident with AI-driven tools, but must also ensure that these recommendations are accurate and not a replacement for clinical judgment.

The use of multiple technologies and platforms may also introduce risks to patient privacy and data security. Safeguarding of sensitive health information is imperative to avoid data breaches that can compromise patient safety and undermine trust in the healthcare system. For example, in 2024, a digital mental health technology company called Confident Health had a data breach of 5.3 terabytes of information which included medical notes, personal documents such as driver’s licenses and insurance cards, and audio and video recordings of personal therapy sessions [26]. Safeguarding patient data and ensuring ethical implementation of these tools are technical challenges that must be mitigated in order to preserve trust and equity in healthcare.

Healthcare providers must be cognizant of the “digital divide,” which poses significant barriers to equitable use of these technologies for patient care. Factors such as individual experience and perception, digital health literacy, cultural beliefs, and lack of access to reliable internet can all affect the ability of patients to benefit from these digital health innovations [27]. Many rural areas in the United States may face broadband accessibility limitations. As of 2024, about 79% of US adults have broadband access at home, and another 15% of U.S. adults are “smartphone-only” internet users [28]. These limitations have greater effects on older, low-income, minority, and non-English speaking populations, who may be susceptible to “digital exclusion” [29]. Concerted efforts to expand broadband infrastructure, increase access to affordable internet, and provide digital literacy programs will be required to overcome these challenges and ensure equitable access.

3.7. Limitations

There are potential limitations in the applicability of this essay. The inductive approach to framework mapping was guided by the authors’ own observations and experiences. Likewise, we made US-centric healthcare system and funding assumptions. As a result, the authors’ experiences may not translate to all other settings. We chose to consider technology broadly, but recognize that individual devices and platforms have important nuances that may be missed in our writing. We hope use of the PRISM contextual factors can help uncover specific implementation details that others should examine. Lastly, we focused on organization/clinician- and patient-level barriers, but recognize that there are barriers that also exist at the community, policy, and society levels with technology implementation.

4. Conclusions

With continued technological advancements, especially in diabetes care, strategic adoption of technology is imperative. Using the PRISM framework can help organize a standardized team-based implementation approach that prioritizes practicality and sustainability. In practice, the next steps should be to prioritize workforce preparation and effective workflow integration through clinician training, establishment of clear team roles, and embedding of continuous feedback and quality improvement processes into routine care. Sustained organizational support will be vital and should include ongoing training, attention to data privacy and security, and strategies to ensure financial sustainability through reimbursement models. Ongoing attention to digital literacy among both clinicians and patients will be essential to ensure equitable access will be essential to long-term success.

Ultimately, we believe interprofessional collaboration transforms technology from a set of tools into a vehicle for improving outcomes, reducing inequities, and strengthening patient trust. By embracing teamwork and open communication, healthcare teams can ensure that the promise of these innovations is realized for all patients with diabetes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and E.N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M. and E.N.; writing—review and editing, J.M. and E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

AI tools (ChatGPT 4o) were used for idea generation, while all writing and analysis were conducted independently.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AID | Automated insulin delivery |

| CCM | Chronic care management |

| CDSS | Clinical decision support software |

| CGM | Continuous glucose monitor |

| DSMES | Diabetes self-management education and support |

| IT | Information technology |

| PRISM | Practical, robust, implementation and sustainability model |

| RE-AIM | Reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance |

| RPM | Remote patient monitoring |

References

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 7. Diabetes Technology: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 (Suppl. 1), S146–S166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherr, J.L.; Heinemann, L.; Fleming, G.A.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Bruttomesso, D.; Hanaire, H.; Holl, R.W.; Petrie, J.R.; Peters, A.L.; Evans, M. Automated Insulin Delivery: Benefits, Challenges, and Recommendations. A Consensus Report of the Joint Diabetes Technology Working Group of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 3058–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Fernandez, J.; Díaz-Soto, G.; Girbes, J.; Arroyo, F.J. Current Perspective on the Potential Benefits of Smart Insulin Pens on Glycemic Control in Patients With Diabetes: Spanish Delphi Consensus. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2025, 19, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, N.S.; Alsubki, N.; Jones, S.; Khunti, K.; Munro, N.; de Lusignan, S. Impact of Information Technology-Based Interventions for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Glycemic Control: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, E.; Roth, L.; Wiencke, K.; Bischoff, C.; Schwarz, P.E. Effect of Multimodal App-Based Interventions on Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e54324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Xu, H.; Jiang, S.; Sung, J.; Sawhney, R.; Broadley, S.; Sun, J. Effectiveness of telemonitoring intervention on glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 201, 110727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, C.; Stichling, S. Clinical Improvements by Telemedicine Interventions Managing Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: Systematic Meta-review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graetz, I.; Huang, J.; Muelly, E.R.; Fireman, B.; Hsu, J.; Reed, M.E. Association of Mobile Patient Portal Access With Diabetes Medication Adherence and Glycemic Levels Among Adults With Diabetes. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e1921429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 5. Facilitating Positive Health Behaviors and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 (Suppl. 1), S86–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parab, R.; Feeley, J.M.; Valero, M.; Chadalawada, L.; Garcia, G.-G.P.; Kar, S.S.; Madabhushi, A.; Breton, M.D.; Li, J.; Shao, H.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in Diabetes Care: Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities Ahead. Endocr. Pract. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.B.; Kim, G.; Jun, J.E.; Park, H.; Lee, J.W.; Hwang, Y.-C.; Kim, J.H. An Integrated Digital Health Care Platform for Diabetes Management With AI-Based Dietary Management: 48-Week Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Xu, Y.; Ballew, S.H.; Coresh, J.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Selvin, E.; Shin, J.-I. Trends and Disparities in Technology Use and Glycemic Control in Type 1 Diabetes. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2526353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayberry, L.S.; Guy, C.; Hendrickson, C.D.; McCoy, A.B.; Elasy, T. Rates and Correlates of Uptake of Continuous Glucose Monitors Among Adults with Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care and Endocrinology Settings. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 2546–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, A.L.; Badlani, S.; Shah, V.N. The Role, Potential Benefits and Cost-effectiveness of Digital Tools for Diabetes Management. Clin. Ther. 2025, 47, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, S.; Arthur, K.; Philip, S.R.; Smallman, R.; Kalra, V.; Yehl, K.; Lee, F.; Kerr, D. Diabetes and Wellness Smartphone Applications for Self-Management Among Adults With Diabetes in the United States. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2025, 19, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levengood, T.W.; Peng, Y.; Xiong, K.Z.; Song, Z.; Elder, R.; Ali, M.K.; Chin, M.H.; Allweiss, P.; Hunter, C.M.; Becenti, A.; et al. Team-Based Care to Improve Diabetes Management: A Community Guide Meta-analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, e17–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurchis, M.C.; Sessa, G.; Pascucci, D.; Sassano, M.; Lombi, L.; Damiani, G. Interprofessional Collaboration and Diabetes Management in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Patient-Reported Outcomes. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siaw, M.Y.L.; Lee, J.Y. Multidisciplinary collaborative care in the management of patients with uncontrolled diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2019, 73, e13288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.D.; Balatbat, C.; Corbridge, S.; Dopp, A.L.; Fried, J.; Harter, R.; Landefeld, S.; Martin, C.; Opelka, F.; Sandy, L.; et al. Implementing optimal team-based care to reduce clinician burnout. NAM Perspect. 2018, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is PRISM? Available online: https://re-aim.org/learn/prism/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Rabin, B.A.; Cakici, J.; Golden, C.A.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Glasgow, R.E.; Gaglio, B. A citation analysis and scoping systematic review of the operationalization of the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM). Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is RE-AIM? Available online: https://re-aim.org/learn/what-is-re-aim/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Espinoza, J.; Shah, P.; Raymond, J. Integrating Continuous Glucose Monitor Data Directly into the Electronic Health Record: Proof of Concept. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2020, 22, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.H.; Afsar-Manesh, N.; Bierman, A.S.; Chang, C.; Colón-Rodríguez, C.J.; Dullabh, P.; Duran, D.G.; Fair, M.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; Hightower, M.; et al. Guiding principles to address the impact of algorithm bias on racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2345050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marey, A.; Arjmand, P.; Alerab, A.D.S.; Eslami, M.J.; Saad, A.M.; Sanchez, N.; Umair, M. Explainability, transparency, and black box challenges of AI in radiology: Impact on patient care in cardiovascular radiology. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2024, 55, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, M. Confidant Health Therapy Records Exposed in Data Breach. Wired. 2024. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/confidant-health-therapy-records-database-exposure/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Lawrence, K. Digital health equity. In Digital Health; Exon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Alkureishi, M.A.; Choo, Z.Y.; Rahman, A.; Ho, K.; Benning-Shorb, J.; Lenti, G.; Velázquez Sánchez, I.; Zhu, M.; Shah, S.D.; Lee, W.W. Digitally Disconnected: Qualitative Study of Patient Perspectives on the Digital Divide and Potential Solutions. JMIR Hum. Factors 2021, 15, e33364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).