The Role of Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes Self-Management on Glycemic Indices: A Cross-Sectional Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

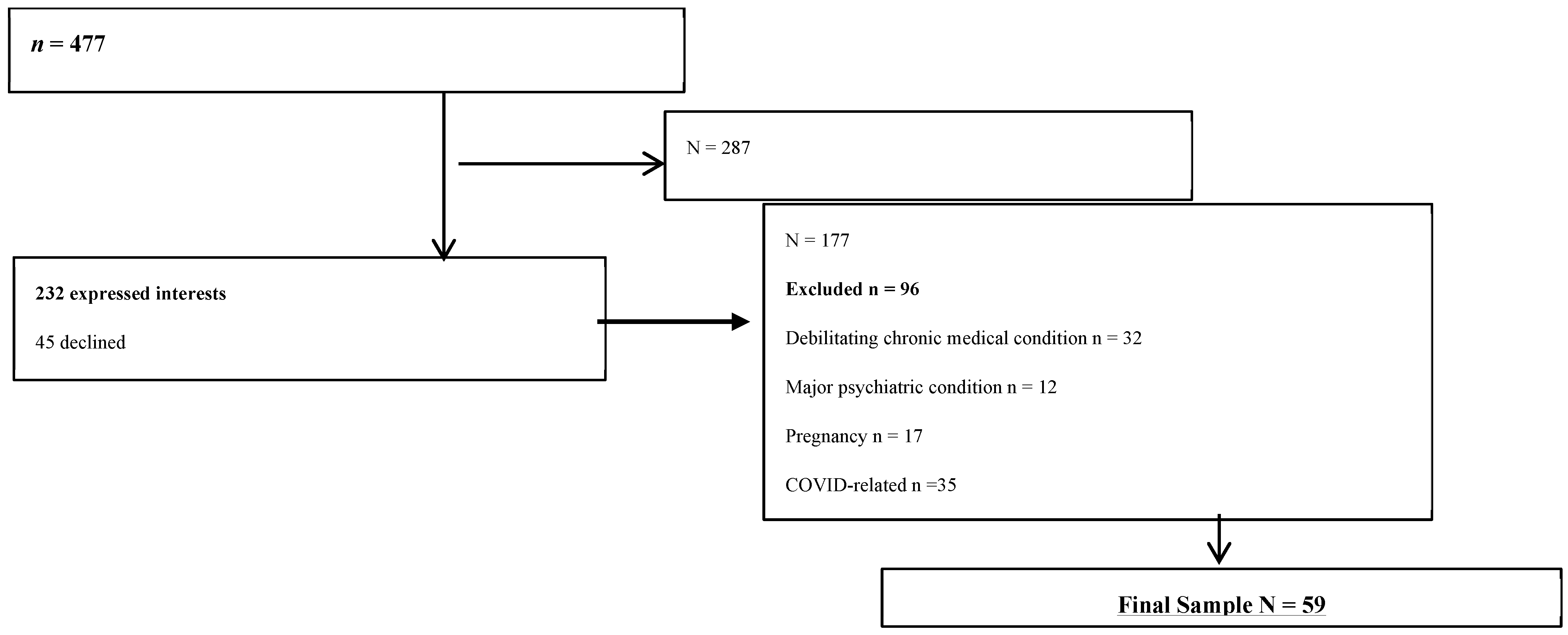

2.2. Settings, Participants, and Recruitment and Data Collection Procedures

3. Measures

3.1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Diabetes Self-Management

3.3. Social Determinants of Health Factors

3.3.1. Food Insecurity

3.3.2. Acculturative Stress

3.3.3. Discriminative Stress

3.4. Glycemia/Glycemic Variability

4. Statistical Analysis

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Limitations

8. Implications for Clinical Practice

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under Curve |

| CIs | Confidence Intervals |

| CGMs | Continuous Glucose Monitors |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| FBHAs | Foreign-Born Haitian Americans (FBHAs) |

| GVP | Glycemic Variability Percentage |

| SDoH | Social Determinants of Health |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| T2D | Type 2 Diabetes |

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/atlas/tenth-edition/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report 2022: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Zheng, Y.; Ley, S.H.; Hu, F.B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magny-Normilus, C.; Whittemore, R.; Wexler, D.J.; Schnipper, J.L.; Nunez-Smith, M.; Fu, M.R. Barriers to type 2 diabetes management among older adult Haitian immigrants. Sci. Diabetes Self-Manag. Care. 2021, 47, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care. 2024, 47 (Suppl. S1), S20–S42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magny-Normilus, C.; Mawn, B.; Dalton, J. Self-management of type 2 diabetes in adult Haitian immigrants: A qualitative study. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2020, 31, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magny-Normilus, C.; Whittemore, R. Haitian immigrants and type 2 diabetes: An integrative review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health. 2020, 22, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, F.G.; Vallasciani, M.; Vaccaro, J.A.; Exebio, J.C.; Zarini, G.G.; Nayer, A.; Ajabshir, S. The association of depression and perceived stress with beta cell function between African and Haitian Americans with and without type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Mellitus 2013, 3, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, R.K.; Conserve, D.F.; Elewonibi, B.; Francis, L.A.; BeLue, R. Diabetes knowledge, management, and prevention among Haitian immigrants in Philadelphia. Diabetes Educ. 2017, 43, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riman, K.A.; Harrison, J.M.; Sloane, D.M.; McHugh, M.D. Self-management and glycemic targets in adult Haitian immigrants with type 2 diabetes: Research protocol. Nurs. Res. 2023, 72, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, J.A.; Exebio, J.C.; Zarini, G.G.; Huffman, F.G. The role of family/friend social support in diabetes self-management for minorities with type 2 diabetes. J. Nutr. Health 2014, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bivins, B.L.; Ruffin, L.; Bivins, M.H.; Lestage-Laforest, M.; Eliezer, C.; Keko, M.; Schroeder-Brown, K.; Singh, A. Diabetes mellitus prevalence among Haitian American Afro-Caribbeans in the United States. J. Natl. Black Nurses Assoc. 2021, 32, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Khalifian, C.E.; Titone, M.; Wooldridge, J.S.; Knopp, K.; Seibert, G.; Monson, C.; Morland, L. Haitian and Haitian American experiences of racism and socioethnic discrimination in Miami-Dade County: At risk and court-involved youth. Fam. Process. 2023, 62, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.A.; Ahmann, A.; Shah, V.N. Type 2 diabetes and the use of real-time continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2021, 23, S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowart, K.; Updike, W.H.; Franks, R. Continuous glucose monitoring in persons with type 2 diabetes not using insulin. Expert. Rev. Med. Devices 2021, 18, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljedaani, S.M.; Siddiqui, A.S.; Raja-Khan, N. Racial and ethnic disparities in CGM use among adults with diabetes. Diabetes 2022, 71, 678-P. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A.K.; Li, T.; Liuzzi, J.P.; Zarini, G.G.; Dorak, M.T.; Huffman, F.G. Genetic associations of PPARGC1A with type 2 diabetes: Differences among populations with African origins. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 921274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, U. Inadequacy of micronutrients, fat, and fiber consumption in the diets of Haitian-, African- and Cuban-Americans with and without type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2012, 82, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exebio, J.C.; Zarini, G.G.; Vaccaro, J.A.; Exebio, C.; Huffman, F.G. Use of hemoglobin A1C to detect Haitian-Americans undiagnosed with type 2 diabetes. J. Braz. Soc. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 56, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danne, T.; Nimri, R.; Battelino, T.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Close, K.L.; DeVries, J.H.; Garg, S.; Heinemann, L.; Hirsch, I.; Amiel, S.A.; et al. International consensus on use of continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1631–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrany, E.A.; Hill-Briggs, F.; Ephraim, P.L.; Myers, A.K.; Garnica, P.; Fitzpatrick, S.L. Continuous glucose monitors and virtual care in high-risk, racial and ethnic minority populations: Toward promoting health equity. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1083145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, P.C.; Chirokas, K.; Keels, J.; Vimalananda, V.G.; Magny-Normilus, C. Race and ethnic disparities in insulin pump and continuous glucose monitor use between 2017 and 2024: A systematic review with a focus on health equity. J. Health Equity 2025, 2, 2444002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebekozien, O.; Fantasia, K.; Farrokhi, F.; Sabharwal, A.; Kerr, D. Technology and heakth inequities in diabetes care: How do we widen access to underserved populations and utilize technology to improve outcomes for all? Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toobert, D.J.; Hampson, S.E.; Glasgow, R.E. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: Results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Escamilla, R.; Dessalines, M.; Finnigan, M.; Hromi-Fiedler, A.; Pachón, H. Validity of the Latin American and Caribbean Household Food Security Scale (ELCSA) in South Haiti. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 871.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussery, K. Accuracy of the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS-5) as a quantitative measure of adherence to inhalation medication in patients with COPD. Ann. Pharmacother. 2014, 48, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paffenbarger RSJr Blair, S.N.; Lee, I.M.; Hyde, R.T. Measurement of physical activity to assess health effects in free-living populations. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1993, 25, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strath, S.J.; Brage, S.; Ekelund, U. Integration of physiological and accelerometer data to improve physical activity assessment. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, S563–S571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, J.N.; Westbrook, F.D. Using the Social, Attitudinal, Familial, and Environmental (S.A.F.E.) Acculturation Stress Scale to assess the adjustment needs of Hispanic college students. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 1996, 29, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hovey, J.D.; King, C.A. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation among immigrant and second-generation Latino adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 1996, 35, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman-Hilliard, C.; Abdullah, T.; Denton, E.G.; Holman, A.; Awad, G. The index of race-related stress-brief: Further validation, cross-validation, and item response theory-based evidence. J. Black Psychol. 2020, 46, 550–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. Freestyle Libre glucose monitoring system. Clin. Diabetes 2018, 36, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, S.; Kim, J.H. Glycemic variability: How do we measure it and why is it important? Diabetes Metab. J. 2015, 39, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; Tennen, H.; Wolpert, H. Continuous glucose monitoring: A review for behavioral researchers. Psychosom. Med. 2012, 74, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, T.; Loehr, S.; Guigard, E.; McCargar, L.J.; Bell, G.J.; Senior, P.; Boulé, N.G. Test-retest reliability of a continuous glucose monitoring system in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2014, 16, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS 9.4. Version 9.4M8; StataCorp: College Station, TX, USA, 2024. Available online: http://www.sas.com/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Levi, R.; Bleich, S.N.; Seligman, H.K. Food insecurity and diabetes: Overview of intersections and potential dual solutions. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1599–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, K.M.; Chesla, C.A.; Kwan, C.M. “So we adapt step by step”: Acculturative experiences affecting diabetes management and perceived health for Chinese American immigrants. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, K.L.; Stuver, S.O.; Cozier, Y.C.; Palmer, J.R.; Rosenberg, L.; Ruiz-Naváez, E.A. Perceived racism and incident diabetes in the Black women’s health study. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 2221–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, B.K.; Hummer, R.A.; Kol, B.; Vega, W.A. The role of discrimination and acculturative stress in the physical health of Mexican-origin adults. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2011, 23, 399–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egede, L.E.; Campbell, J.A.; Walker, R.J.; Linde, S. Structural racism as an upstream social determinant of diabetes outcomes: A scoping review. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-McNeil, J.; Edwards, C.L.; Batch, B.C.; Benbow, D.; McDougald, C.S.; Sharpe, D. A cultural targeted self-management of program for African Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2012, 44, 126–141. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, P. The effect of a diabetes self-management program for African Americans in a faith-based setting (pilot study). Diabetes Manag. 2017, 7, 1758–1907. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, P.C.; Ruscitti, B.; Nguyen, T.; Magny-Normilus, C.; Wentzell, K.; Watts, S.A.; Bowser, D. A health systems approach to nurse-led implementation of diabetes prevention and management in vulnerable populations. Health Syst. Reform. 2025, 11, 2503648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittemore, R.; Vilar-Compte, M.; Burrola-Méndez, S.; Lozano-Marrufo, A.; Delvy, R.; Pardo-Carrillo, M.; De La Cerda, S.; Pena-Purcell, N.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Development of a diabetes self-management + mHealth program: Tailoring the intervention for a pilot study in a low-income setting in Mexico. Pilot. Feasibility Stud. 2020, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, Y.; Dowling, D.J. Facilitating adherence to evidence-based practices for adults with type 2 diabetes. J. Nurse Pract. 2021, 17, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magny-Normilus, C.; Luppino, F.; Lyons, K.; Luu, J.; Taylor, J.Y. Food insecurity and diabetes management among adults of African descent: A systematic review. Diabet. Med. 2024, 41, e15398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canedo, J.R.; Miller, S.T.; Schlundt, D.; Fadden, M.K.; Sanderson, M. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Diabetes Quality of Care: The Role of Healthcare Access and Socioeconomic Status. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2018, 5, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, R.B.; Gonzalez, A.G.; Shah, V.N.; Rasmussen, C.G.; Akturk, H.K.; Pyle, L.; Forlenza, G.; Alonso, G.T.; Snell-Bergeon, J. Racial Disparities in Diabetes Technology Adoption and Their Association with HbA1c and Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2023, 16, 2295–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (A) | |||

| Characteristic | N = 59 | Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

| Age | 51.7 (9.9) | ||

| Sex (Female) (Male) | 30 (50.8%) 29 (49.2%) | ||

| Duration of T2D | 7.7 (6.8) | ||

| Weight (lb) | 163.7 (17.9) | ||

| Overweight/Obese | (28.8/20.9) | ||

| Marital Status (Married) | 30 (52.6%) | ||

| Education (≤HS) | 11 (19.6%) | ||

| Annual Income No. of Comorbid Conditions | 47,694 (21,880) 1.63 (1.30) | ||

| (B) | |||

| Metric | Mean (SD) | n (%) | |

| Average glucose (70–126 gm/dL) | 98.3 | 40.8% | |

| Glucose SD (% 20 mg/dL) | 20.9 | 15.6% | |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | 20.3 | 7.5% | |

| Time < 70 mg/dL | 21.4 | 25.6% | |

| Time 70–180 mg/dL | 72.1 | 27.1% | |

| Time > 180 mg/dL | 2.8 | 10.2% | |

| (C) | |||

| Domain | Subscales | Mean (SD) | N (%) |

| DSM | SDSCA—General diet | 4.6 | (2.0) |

| DSM | SDSCA—Exercise | 2.6 | (2.3) |

| Medication Adherence | MARS-5 | 4.0 | (2.4) |

| Food Security | ELCSA | 5.4 | (4.0) |

| Stress | SAFE | 47.9 | (20.7) |

| Stress | IRRS-Brief | 51.9 | (21.7) |

| Average Daily Glucose Spearman Coeff. | CV of Glucose Spearman Coeff. | SD of Glucose Spearman Coeff. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| No. of Comorbid Conditions | 0.192 | 0.138 | 0.216 |

| Weight | 0.276 | 0.000 | 0.009 |

| Age | 0.102 | 0.107 | 0.164 |

| Income | 0.036 | −0.068 | −0.044 |

| Duration of Diabetes | 0.054 | 0.240 | 0.244 |

| SDSCA | |||

| General Diet | −0.219 | −0.025 | −0.071 |

| Specific Diet | −0.082 | −0.042 | |

| Exercise | 0.032 | −0.158 | 22,120.100 |

| Foot Care | −0.003 | 0.098 | 0.061 |

| Diet | −0.090 | 0.057 | 0.038 |

| Medication | 0.149 | 0.104 | 0.106 |

| Physical Activity Score | |||

| PA-WD | 0.228 | −0.136 | −0.061 |

| PA-WE | 0.200 | −0.133 | −0.074 |

| PA-Total | 0.221 | −0.130 | −0.060 |

| Medication Adherence | |||

| MARS5 Total | −0.095 | −0.205 | −0.212 |

| Food Security | |||

| Food Security with Minors | * −0.296 | 0.200 | 0.139 |

| Food Security with Member Only | * −0.288 | 0.240 | 0.197 |

| SAFE Total | |||

| SAFE Acculturative Stress | 0.165 | 0.199 | * 0.276 |

| Racial Stress | |||

| Total of Race-Related Stress | 0.176 | * 0.309 | * 0.396 |

| Model: Daily Glucose Level (Log-Transformed) | |||||

| (A) Raw Sample (n = 50) | (B) Bootstrapping Sample (1000 Repeats) | ||||

| Coefficient | StdErr | p-value | Coefficient | 95% CI | |

| Weight | 0.246 | 0.136 | 0.0768 | 0.251 | (0.242, 0.259) |

| General Diet | −0.242 | 0.143 | 0.0982 | −0.236 | (−0.242, −0.230) |

| Food Security with Member | −0.324 | 0.149 | 0.0349 | −0.326 | (−0.331, −0.320) |

| Model: Daily Variability of Glucose (Standard Deviation) | |||||

| (A) Raw Sample (N = 57) | (B) Bootstrapping Sample (1000 Repeats) | ||||

| Coefficient | StdErr | p-value | Coefficient | 95% CI | |

| Duration of Diabetes | 0.256 | 0.107 | 0.0205 | 0.282 | (0.273, 0.291) |

| MARS5 Total | −0.365 | 0.114 | 0.0023 | −0.361 | (−0.367, −0.356) |

| Race-Related Stress | 0.447 | 0.119 | 0.0004 | 0.460 | (0.443, 0.467) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magny-Normilus, C.; Jeon, S.; Schnipper, J.L.; Wu, B.; Whittemore, R. The Role of Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes Self-Management on Glycemic Indices: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Diabetology 2025, 6, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120154

Magny-Normilus C, Jeon S, Schnipper JL, Wu B, Whittemore R. The Role of Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes Self-Management on Glycemic Indices: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Diabetology. 2025; 6(12):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120154

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagny-Normilus, Cherlie, Sangchoon Jeon, Jeffrey L. Schnipper, Bei Wu, and Robin Whittemore. 2025. "The Role of Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes Self-Management on Glycemic Indices: A Cross-Sectional Analysis" Diabetology 6, no. 12: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120154

APA StyleMagny-Normilus, C., Jeon, S., Schnipper, J. L., Wu, B., & Whittemore, R. (2025). The Role of Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes Self-Management on Glycemic Indices: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Diabetology, 6(12), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120154