Abstract

Purpose: It has been previously described that some women with type 1 diabetes (T1D) may experience changes in glucose levels in relation to their menstrual cycle. However, whether an advanced hybrid closed-loop system (AHCL) can mitigate these cycle-dependent changes is yet to be determined. Methods: This study is a prospective analysis of a cohort of premenopausal women with T1D with spontaneous menstrual cycles who are users of an AHCL system 780G Medtronic®. Three consecutive cycles were analyzed for each patient, and each cycle was divided into three phases (menstrual, luteal, and rest of cycle phase). Results: Fifteen subjects were included. Mean age was 38 ± 7.6 years, HbA1c was 7.12 ± 0.7%, and diabetes duration was 21 ± 13.7 years. Mean glucose was higher in the luteal phase compared to the menstrual period (p = 0.029 luteal vs. menstrual) and the rest of the cycle (p = 0.018 luteal vs. rest of cycle). The time in range (TIR) was lower in the luteal phase compared to the rest of cycle phase (p = 0.015 luteal vs. rest of cycle). The time below range (TBR) was significantly higher in the menstrual compared to the luteal phase (p = 0.007 luteal vs. menstrual). Daily insulin requirements were higher in luteal phase compared to rest of cycle (p = 0.017 luteal vs. rest of cycle). Conclusions: A higher mean glucose and lower TIR, despite a higher total insulin dose, was observed in the luteal phase. A higher TBR was observed in the menstrual phase. However, AHCL with 780G Medtronic® achieves a TIR of almost 70% in all cycle phases.

1. Introduction

It has been previously described that a considerable percentage of women affected by type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) may experience changes on their glucose levels in relation to their menstrual cycle [1], and this can lead to a worsening on their glucose control or a higher risk of complications. In fact, a study published in 1942 reported that, in a cohort of 36 women with T1D, up to 50% presented an acute diabetes complication such as ketoacidosis (DKA) during their menstrual period [2]. Following this, two previous observational studies [3,4] analyzed glycemic control in women with T1D based on capillary glycemia throughout their menstrual cycle. In this case, both studies observed a worsening of glucose levels in the luteal phase, with high glucose levels maintained all day but without changes to glucose levels before breakfast.

More recent studies have assessed glycemic control in relation to the menstrual cycle, but with the use of new technologies used for diabetes management, such as continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). In this regard, in 2004, Goldner et al. [5] evaluated glycemic control and hormonal levels (estrogen and progesterone) in four patients treated with multiple insulin doses (MDI) for three consecutive cycles, observing an increase in glucose levels in the luteal phase in some of the patients, coinciding with a progesterone peak in this second phase of the cycle. Other studies published later on, including a total of 6 [6], 12 [7], and 24 [8] patients also using glucose sensors (on MDI treatment or insulin infuser users), also observed a worsening of glycemic control on the second phase of the cycle.

Moving forward, newer technology associated with T1D management includes advanced hybrid closed-loop (AHCL) systems, where a mathematical algorithm controls insulin infusion through an insulin pump, according to glucose levels obtained from CGM. Nowadays, AHCL systems are considered the gold standard for diabetes management due to their positive outcomes as to glucose control and self-reported satisfaction by the patient. However, to date, there is not enough evidence as to whether these closed-loop systems can help and detect glucose cycle-dependent changes. A study by Levy et al. [9], for instance, included a total of 16 users of an AHCL system, performing interpatient analysis, and did not observe differences between the different cycle phases in relation to glucometric variables or insulin infusion. However, other studies have found differences as to glycemic control between the different phases, and users were still required to manually adjust their therapy according to the cycle phase and insulin sensitivity at that time [10,11].

Regarding the pathophysiological mechanisms that could explain this relationship between the menstrual cycle and glycemic control, it seems that changes in progesterone levels during the different cycle phases could act on insulin resistance, hence increasing the risk of hyper or hypoglycemia [12,13]. On the other hand, it has also been speculated whether changes in carbohydrate intake, physical activity, or the presence of premenstrual syndrome could also play a role in these glycemic changes, although without conclusive results.

Hence, the aim of this study was to the assess glycemic profile, insulin requirements, and carbohydrate intake in the different phases of the menstrual cycle in women with T1D who are users of AHCL systems.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

A prospective analysis of a cohort of women with T1D attending regular follow-up appointments in the Diabetes Unit of the Endocrinology and Nutrition Department of Hospital del Mar (Barcelona) was performed. Due to the nature of the study, no adjustments for possible confounding factors were made. The inclusion period was from November 2023 to September 2024. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution (approval code: 2023/11155, approval date: 21 November 2023). Consent was obtained from each patient after a full explanation of the purpose of the study.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: premenopausal women with T1D, >18 years old, spontaneous menstrual cycle of a duration of 24 to 35 days, users of AHCL system 780G Medtronic(Medtronic, Tokyo, Japan) (Medtronic insulin pump using ultra-fast acting insulin analog, and Guardian G4 glucose sensor). Exclusion criteria included the following: modifications in diabetes treatment 3 months before inclusion, pregnancy and lactation, under treatment with hormonal oral contraceptive pills, language barrier, under treatment with corticosteroids, <70% of information of AHCL system available regarding insulin infusion and glucometric data.

An initial visit was carried out where the sociodemographic variables and those related to diabetes and insulin treatment were collected. Subsequently, the patient was then instructed to record their first day of menstrual bleeding for the next 3 menstrual cycles.

The patient then continued with her usual treatment with the AHCL system 780G Medtronic and regular follow-up appointments. No adjustment of ACHL parameters such as glucose target, insulin/carbohydrate ratio, or active insulin duration was performed between the first and second medical appointment.

Finally, a second face-to-face appointment in the outpatient clinic was scheduled after the 3 menstrual cycles. In this appointment, all information regarding glucometric variables, insulin administration, and carbohydrate intake was collected from the CareLinkTM System platform.

The CareLinkTM System platform is where all the information regarding insulin administration and carbohydrate intake from the insulin pump, as well as glucometric variables from the glucose sensor, is automatically uploaded to the system, without the patient having to introduce any data manually. Hence, due to the automatic upload, it was not necessary to clean any values.

2.2. Study Variables

The following parameters were collected for all patients including social demographic variables (age, toxic habits, comorbidities, usual treatment) and diabetes-related variables (diabetes duration, presence of micro or macrovascular complications, HbA1c).

Each menstrual cycle was divided into 3 phases: menstruation (vaginal bleeding), luteal phase (9 days before menstruation, in order to ensure an interval of time englobing the mid to late luteal phase), and rest of cycle (days between menstruation and the luteal phase, including the follicular phase).

Moreover, the following variables were collected for all cycle phases of the 3 consecutive cycles: glucometric variables (mean glucose, time above range > 250 mg/dL [TAR], time in range 70–180 mg/dL [TIR], time below range < 70 mg/dL [TBR], coefficient of variation [CV]), insulin administration variables (total daily dose, basal insulin dose/24 h and prandial insulin dose/24 h), intake variables (carbohydrate intake quantity/24 h).

2.3. Outcomes

The main outcome of the present study was to assess changes in TIR during the different phases of the menstrual cycle.

Secondary outcomes included differences as to mean glucose, GMI, TBR, TAR, CV, insulin dose, and carbohydrate intake in the different cycle phases.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The results are represented as percentages (categorical variables), mean +/− standard deviation (continuous variables with normal distribution), or medians with interquartile range (continuous variables with non-normal distribution). The normality of the variables was analyzed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnoff test.

The difference between postprandial and preprandial glucose levels values (Δglucose) was calculated for breakfast, lunch, and dinner in each cycle phase. Preprandial glucose was calculated according to the moment carbohydrate intake was announced, and postprandial glucose 2 h after that.

A repeated measures ANOVA test was used to evaluate the presence of at least 1 difference between the different phases of the menstrual cycle.

All calculations were performed with the SPSS software package (version 19.0 for Windows, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and a two-sided p value < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

3. Results

The present study included a total of 15 women with previous T1D diagnosis who were users of the AHCL system 780G Medtronic.

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

The mean age of the total cohort was 38 ± 7.6 years, with a mean diabetes duration of 21 ± 13.7 years and mean Hb1Ac of 7.12 ± 0.7%. The rest of the baseline characteristics of the included patients are further detailed in Table 1. A total of 45 phases were finally analyzed. All patients were in auto-mode >95% of the time, with 12 (80%), 1 (6%), and 2 (14%) women having a glucose target set up in 100 mg/dL, 110 mg/dL, and 120 mg/dL, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included patients.

3.2. Glucometric Variables and Insulin Requirements

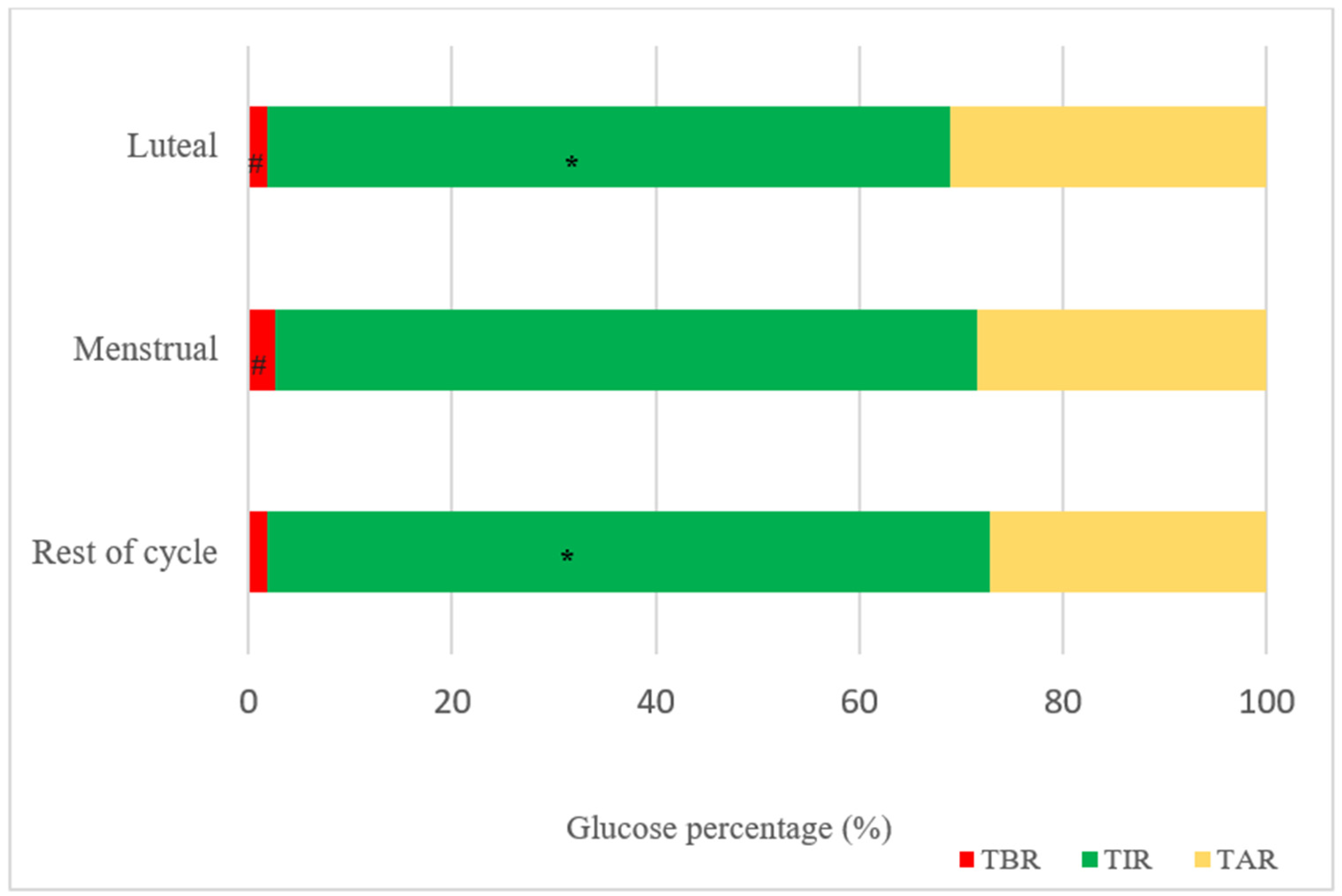

All the results regarding different cycle phases are detailed in Table 2. Mean glucose was higher in the luteal phase (161.4 ± 17.9 mg/dL) compared to the menstrual phase (155.4 ± 20.3 mg/dL) and the rest of the cycle (155.5 ± 19.9 mg/dL). TIR was lower in the luteal phase (67.15 ± 12.1%) compared to the rest of the cycle (71.0 ± 12.3%) and TBR was significantly higher in the menstrual phase (2.5 ± 1.8%) compared to the luteal phase (1.8 ± 1.4%).

Table 2.

Glucometric variables and insulin requirements in the different cycle phases.

Significant differences were also observed regarding total daily insulin requirements, being higher in the luteal phase (0.58 ± 0.2 U/kg) compared to the menstrual phase (0.53 ± 0.2 U/kg) and the rest of the cycle (0.52 ± 0.2 U/kg).

The results regarding total insulin requirements, as well as TAR, TIR, and TBR in the different cycle phases, are also further detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Glucometric results of the different cycle phases. TBR: time below range; TIR: time in range; TAR: time above range. * p = 0.015 (difference in TIR luteal vs. rest of cycle phase); # p = 0.007 (difference in TBR luteal vs. menstrual phase).

3.3. Fasting Glucose and ΔGlucose After Carbohydrate Intake Announcement

Mean fasting glucose levels were 137.9 ± 22.3 mg/dL, 141.3 ± 31.8 mg/dL, and 146.3 ± 39.9 mg/dL for the luteal, menstrual, and rest of cycle phases (p = 1.00 luteal vs. menstrual, p = 0.928 luteal vs. rest of cycle and p = 1.000 menstrual vs. rest of cycle).

As for the change in glucose levels according to the different meals, no statistically significant differences were observed between cycle phases with regard to Δglucose 2 h after breakfast [32 (20–+47) mg/dL luteal, 23 (−6–+75) mg/dL menstrual and 15 (−5–+40) mg/dL rest of cycle phase (p = 0.420)] and lunch [18 (−21–+59) mg/dL luteal, 18 (−28–+49) mg/dL menstrual and 3 (−11–+30) mg/dL rest of cycle phase (p = 0.627)].

However, a change in glucose 2 h after dinner was −5 (−28–+44) mg/dL in the luteal, −10 (−40–+15) mg/dL the menstrual, and 0 (−14–+29) mg/dL in the rest of cycle phase (p = 0.015).

3.4. Carbohydrate Intake

No significant differences were observed as to carbohydrate intake between phases (122.5 ± 52.8 g. luteal, 114.3 ± 46.5 g. menstrual and 112.6 ± 35.3 g. rest of cycle; p = 0.225 menstrual vs. luteal; p = 1.000 menstrual vs. rest of cycle and p = 0.437 luteal vs. rest of cycle).

4. Discussion

This study reveals significant findings regarding the relationship between T1D and menstruation, highlighting glycemic variability across the different cycle phases. In particular, a higher mean glucose level and lower TIR, despite higher total insulin dose, was observed in the luteal phase. On the contrary, a higher TBR was observed in the menstrual phase. No significant differences were observed as to carbohydrate intake in the different cycle phases. These findings provide valuable information into how biological changes occurring during the menstrual cycle may affect diabetes control in women with T1D, and the role that AHCL systems can play to mitigate these cycle-dependent changes. Hence, although we observed that AHCL systems improved overall glycemic control, they did not prevent the natural fluctuations between cycle phases.

As previously described, it has been acknowledged that some women with T1D diagnosis may experience changes in glucose levels and insulin requirements during the different phases of the menstrual cycle [8,11]. In this regard, Herranz et al. [3], with the use of CGM, observed that 2/3 women experienced a higher rate of hyperglycemic events during the luteal phase, as confirmed in other studies [7] and in line with our results. Following this line of inquiry, a very recent study also observed that, for 13 women with T1D, when switching from sensor-augmented pump therapy to an ACHL, although pre-existing differences in TBR < 70 were eradicated (3.5 ± 3.2% vs. 3.0 ± 3.0%), TIR became significantly higher during the early follicular phase compared to during the late luteal phase (79.1 ± 9.3% vs. 74.5 ± 10.0%) [14]. Hence, the increased glucose levels observed in the luteal phase in all these studies may be explained, at least in part, by a higher insulin resistance state secondary to elevated progesterone levels [8]. In this sense, the role of hormone levels and their effect on insulin sensitivity has been described in previous publications [15,16]. In our study, despite the higher insulin administration in the luteal phase, the algorithm probably does not react quickly enough to mitigate the insulin resistance state when entering the luteal phase. Moreover, more recently, Li et al. [17] also evaluated the effect of the menstrual cycle on glycemic control, in this case also including women under hormonal contraception treatment. No differences were observed as to glucose trends in the different cycle phases when comparing women with/without hormonal contraception, suggesting that hormone control may not be enough to mitigate the hyperglycemic state in the luteal phase.

In addition to hormonal changes, another possible explanation for the glucose variability between phases could be the modification of the intake pattern during the menstrual cycle. In the present study, we observed a tendency towards a higher carbohydrate intake in the luteal phase in comparison to the other phases, complementing the findings of other studies [17], which could also play a part in the higher glucose levels observed. However, other possible associated factors such as the glycemic index of the carbohydrates consumed, food cravings, increased consumption of processed food, and psychological stress were not assessed in the present study but could shed light on this matter in future studies.

As for the menstrual phase, a higher TBR, despite a trend towards a lower insulin dosage, was observed in the present study. A possible explanation for the higher TBR during menstruation in our patients could be the decline in progesterone levels and hence insulin resistance, these hormonal changes being faster than the algorithm automatic insulin infusion adjustment. However, these results contradict those previously observed by Mesa et al. [14] and Elhenawy et al. [18]. Interestingly, both studies evaluated the same AHCL as our study, detecting a higher TBR in the menstrual phase during the open-loop or sensor-augmented pump period, but with a mitigation of these differences when initiating the automated closed-loop algorithm. In this same line, more recently, Monroy et al. [19] with the same AHCL system, also observed a higher average glucose and higher total insulin dose in the luteal phase but with similar results with regard to the other glucometric variables (including TBR) across the different cycle phases. However, it must be acknowledged that most of the patients included in these studies presented good glycemic control at baseline, achieving International Consensus Targets (TIR > 70%, TBR < 4%, TAR < 25% and CV ≤ 36%), which probably makes it harder to detect glucometric differences between the different cycle phases [20].

Hence, according to the results of the present study, the next question we should ask ourselves is if any parameter could be adjusted in daily clinical practice in order to overcome these cycle phase differences. Interestingly, we observed a more significant decline in glucose levels 2 h after dinner in the menstrual phase compared to the luteal and rest of cycle phases. We could therefore speculate that the higher TBR observed in this period could be explained, at least in part, by excessive insulin administration at dinner. Hence, adjusting the insulin/carbohydrate ratio for dinner during menstruation could presumably decrease the time spent in hypoglycemia in this period. On the contrary, as no differences were observed between cycle phases concerning fasting glucose, then the adjustment of glucose target or basal rate would not be necessary. However, we believe further research involving intervention studies with different commercialized AHCL systems is mandatory to validate the proposed clinical adjustments described in this study.

The main limitation of the present study is the fact that hormonal levels were not available in order to evaluate the different phases of the menstrual cycle, but instead menstruation was self-recorded by the patient based on their first day of bleeding, and then the other cycle phases were calculated according to that, as one of the inclusion criteria was a spontaneous menstrual cycle. Secondly, carbohydrate intake was also self-recorded by the patient, and data on physical activity or psychological aspects such as food craving not announced to the AHCL system, or premenstrual syndrome, were not available. Moreover, the limited sample size should also be considered, although three cycles were analyzed for each patient. Finally, only one AHCL system was evaluated; hence, the results cannot be extrapolated to the other currently commercialized systems used in T1D daily clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

In women with T1D who are users of an AHCL system, a higher mean glucose and lower TIR, despite a higher total insulin dose, was observed in the luteal phase. On the contrary, a higher TBR was observed in the menstruation phase. However, ACHL with 780G Medtronic® achieves a TIR of almost 70% in all cycle phases. Futures studies are mandatory to fully assess the role of commercialized AHCL systems regarding glucose management in the different cycle phases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.-M., G.L. and J.A.F.-L.R.; data curation, V.A., A.G. (Anna Garrido), R.G. and G.N.; formal analysis, J.J.C. and A.G. (Andrea González).; investigation, M.F.-M. and J.J.C.; methodology, M.F.-M. and M.R.-F.; supervision, E.C., J.J.C. and J.A.F.-L.R.; writing—original draft, M.R.-F.; writing—review and editing, E.C. and J.J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of our institution (Hospital dell Mar, Barcelona, code: Barcelona 2023/11155, date 21 November 2023). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Levy, C.J.; Widom, B.; Simonson, D. Effect of the menstrual cycle on glucose metabolism and diabetes control in women with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Semin. Reprod. Med. 1994, 12, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, H.I. The influence of menstruation on carbohydrate tolerance in diabetes mellitus. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1942, 47, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Herranz, L.; Saez-De-Ibarra, L.; Hillman, N.; Gaspar, R.; Pallardo, L.F. Glycemic changes during menstrual cycles in women with type 1 diabetes. Med. Clin. 2016, 146, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunt, H.; Brown, L.J. Self-reported Changes in Capillary Glucose and Insulin Requirements During the Menstrual Cycle. Diabet. Med. 1996, 13, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldner, W.S.; Kraus, V.L.; Sivitz, W.I.; Hunter, S.K.; Dillon, J.S. Cyclic Changes in Glycemia Assessed by Continuous Glucose Monitoring System During Multiple Complete Menstrual Cycles in Women with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2004, 6, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barata, D.S.; Adan, L.F.; Netto, E.M.; Ramalho, A.C. The Effect of the Menstrual Cycle on Glucose Control in Women with Type1 Diabetes Evaluated Using a Continuous Glucose Monitoring System. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.A.; Jiang, B.; McElwee-Malloy, M.; Wakeman, C.; Breton, M.D. Fluctuations of Hyperglycemia and Insulin Sensitivity Are Linked to Menstrual Cycle Phases in Women With T1D. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2015, 9, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatulashvili, S.; Julla, J.B.; Sritharan, N.; Rezgani, I.; Levy, V.; Bihan, H.; Riveline, J.P.; Cosson, E. Ambulatory Glucose Profile According to Different Phases of the Menstrual Cycle in Women Living With Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, 2793–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, C.J.; O’Malley, G.; Raghinaru, D.; Kudva, Y.C.; Laffel, L.M.; Pinsker, J.E.; Lum, J.W.; Brown, S.A.; iDCL Trial Research Group. Insulin Delivery and Glucose Variability Throughout the Menstrual Cycle on Closed Loop Control for Women with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2022, 24, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mewes, D.; Wäldchen, M.; Knoll, C.; Raille, K.; Braune, K. Variability of Glycemic Outcomes and Insulin Requirements Throughout the Menstrual Cycle: A Qualitative Study on Women With Type 1 Diabetes Using an Open-Source Automated Insulin Delivery System. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2023, 17, 1304–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, C.J.L.; Fabris, C.; Breton, M.D.; Cengiz, E. Insulin Replacement Across the Menstrual Cycle in Women with Type 1 Diabetes: An In Silico Assessment of the Need for Ad Hoc Technology. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2022, 24, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widom, B.; Diamond, M.P.; Simonson, D.C. Alterations in Glucose Metabolism During Menstrual Cycle in Women With IDDM. Diabetes Care 1992, 15, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, I.A.; Scott, A.R.; Bowman, C.A.; Jeffcoate, W.J. Effect of Phase of Menstrual Cycle on Insulin Sensitivity, Peripheral Blood Flow and Cardiovascular Responses to Hyperinsulinaemia in Young Women with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabet. Med. 1990, 7, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesa, A.; Solà, C.; Vinagre, I.; Roca, D.; Granados, M.; Pueyo, I.; Cabré, C.; Conget, I.; Giménez, M. Impact of an Advanced Hybrid Closed-Loop System on Glycemic Control Throughout the Menstrual Cycle in Women with Type 1 Diabetes Prone to Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2024, 26, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trout, K.K.; Rickels, M.R.; Schutta, M.H.; Petrova, M.; Freeman, E.W.; Tkacs, N.C.; Teff, K.L. Menstrual Cycle Effects on Insulin Sensitivity in Women with Type 1 Diabetes: A Pilot Study. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2007, 9, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, F.; Wanatabe, M.; Schoonjans, K.; Lydon, J.; O’Malley, B.W.; Auwerx, J. Progesterone receptor knockout mice have an improved glucose homeostasis secondary to β-cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15644–15648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yardley, J.E.; Zaharieva, D.P.; Riddell, M.C.; Gal, R.L.; Calhoun, P. Changing Glucose Levels During the Menstrual Cycle as Observed in Adults in the Type 1 Diabetes Exercise Initiative Study. Can. J. Diabetes 2024, 48, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhenawy, Y.I.; Kader, M.S.A.; Thabet, R.A. Performance of the MiniMed 780G system on mitigating menstrual cycle-dependent glycaemic variability. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 4916–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monroy, G.; Picón-César, M.J.; García-Alemán, J.; Tinahones, F.J.; Martínez-Montoro, I.J. Glycemic control across the menstrual cycle in women with type 1 diabetes using the MiniMed 780G advanced hybrid closed-loop system: The 780MENS prospective study. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2025, 27, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, R.I.G.; DeVries, J.H.; Hess-Fischl, A.; Hirsch, I.B.; Kirkman, M.S.; Klupa, T.; Ludwig, B.; Nørgaard, K.; Pettus, J.; Renard, E.; et al. The management of type 1 diabetes in adults. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia 2021, 64, 2609–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).