Abstract

Background/Objectives: Diabetic foot infections (DFIs) are a leading cause of hospitalization, amputation, and costs among patients with diabetes. Although early treatment is assumed to reduce complications, its real-world effects remain uncertain. We applied a causal machine-learning (ML) approach to investigate whether early DFI treatment improves hospitalization and clinical outcomes. Methods: We conducted an observational study using de-identified UCSF electronic health record (EHR) data from 1434 adults with DFI (2015–2024). Early treatment (<3 days after diagnosis) was compared to delayed/no treatment (≥3 days or none). Outcomes included DFI-related hospitalization and lower-extremity amputation (LEA). Confounders included demographics, comorbidities, antidiabetic medication use, and laboratory values. We applied Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation (TMLE) with SuperLearner, a machine-learning ensemble. Results: Early treatment was associated with higher hospitalization risk (TMLE risk difference [RD]: 0.293; 95% CI: 0.220–0.367), reflecting the triage of clinically sicker patients. In contrast, early treatment showed a protective trend against amputation (TMLE RD: −0.040; 95% CI: −0.098 to 0.066). Results were consistent across estimation methods and robust to bootstrap validation. A major limitation is that many patients likely received treatment outside UCSF, introducing uncertainty around exposure classification. Conclusions: Early treatment of DFIs increased hospitalization but reduced amputation risk, a paradox reflecting appropriate clinical triage and systematic exposure misclassification from fragmented healthcare records. Providers prioritize the sickest patients for early intervention, leading to greater short-term utilization but potentially preventing irreversible complications. These findings highlight a cautionary tale; even with causal ML, single-institution analyses may misrepresent treatment effects, underscoring the need for causally informed decision support and unified EHR data.

1. Introduction

Diabetic foot infections (DFIs) are among the most serious and costly complications of diabetes, accounting for a substantial share of hospitalizations, amputations, and healthcare expenditures worldwide [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. In the United States, DFIs are the leading cause of diabetes-related hospital admissions, representing approximately 20% of all inpatient encounters for people with diabetes [15,16]. Hospital care alone constitutes over 50% of the national cost burden of diabetes, and up to one-third of diabetes-related healthcare expenditures are directly attributable to the management of foot ulcers and infections [17,18].

Delays in treatment can have serious consequences. Observational studies have shown that prolonged time to referral or initiation of appropriate care is linked to significantly higher rates of poor outcomes, including lower-extremity amputations (LEAs) and in-hospital mortality [19]. For instance, Lin et al. found that patients referred for DFI care more than 59 days after symptom onset had more than double the rate of poor outcomes compared to those referred earlier (21.21% vs. 10.47%); each day of delay incrementally worsened prognosis [19].

Despite strong clinical consensus favoring early treatment of diabetic foot infections (DFIs), the real-world effectiveness of prompt management remains uncertain due to challenges such as high recurrence rates, patient nonadherence, and limitations of observational studies [1,15,17,19]. Recent advances in causal inference offer more robust alternatives. In particular, Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation (TMLE) provides a doubly robust framework that combines machine learning with semi-parametric inference to adjust for confounding and model misspecification simultaneously [20,21]. TMLE is specifically designed for use in complex observational settings where traditional modeling assumptions might not hold, and where both treatment assignment and outcomes are influenced by many correlated covariates [20]. By using ensemble machine-learning via SuperLearner, TMLE can flexibly estimate both outcome and propensity models while minimizing overfitting, making it especially well-suited to healthcare applications with noisy, high-dimensional, or sparsely populated data [22].

Before evaluating treatment timing, this study addresses three fundamental challenges for real-world healthcare analytics. First, confounding by indication arises when clinicians appropriately triage high-risk patients, creating systematic differences between treatment groups that mimic treatment harm. Second, exposure misclassification from fragmented care occurs when patients treated outside the UCSF system are classified as “untreated,” distorting apparent treatment effects. Third, the limits of machine-learning that relies on incomplete data remind us that even advanced causal methods cannot fully account for missing or externally siloed information. These challenges motivate a “cautionary tale” framing: causal machine learning can reveal, but not resolve, biases inherent to current healthcare data infrastructure.

In this study, we apply TMLE to assess the effect of early treatment—defined as DFI-specific interventions initiated within 3 days of diagnosis—on the risk of hospitalization using de-identified EHR data from UCSF. By comparing patients who received early treatment to a comparison group consisting of patients who received delayed (≥3 days) or no treatment, and adjusting for a rich set of demographic, clinical, laboratory, and medication variables, we aim to uncover whether early intervention truly improves outcomes or if the apparent benefits (or harms) in prior studies are artifacts of selection bias. Our findings provide clinical insights, but also demonstrate how causal machine learning methods can uncover hidden biases in observational healthcare data and reshape our understanding of real-world treatment effectiveness. Using comprehensive EHR data structured according to the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model, we analyzed 1434 patients with DFI to estimate causal treatment effects while adjusting for complex confounding patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Cohort

Using UCSF de-identified EHR data, this retrospective observational study included adult patients (≥18 years) who were diagnosed with DFI between January 2015 and December 2024. We excluded patients with missing diabetes diagnosis data or insufficient follow-up.

2.2. Treatment Definition (Validation)

DFI treatment was defined as receipt of validated antibiotics or procedures specifically indicated for diabetic foot infections. Treatment identification used a two-step validation process.

2.2.1. Clinical Curation

We developed reference standards of clinically appropriate interventions (129 DFI-related procedures; 261 DFI-appropriate antibiotics) based on clinical literature and diabetes foot care guidelines.

2.2.2. Technical Validation

All concept IDs were verified against UCSF OMOP vocabularies to ensure validity and obtain standardized concept names.

2.3. Treatment Inclusion and Timing

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- -

- Restricted to non-inpatient settings (outpatient visits, emergency departments, office visits, and ambulatory care facilities; OMOP visit concept IDs: 9202, 9203, 581477, 38004208, 38004225, 38004247, 581479).

- -

- Occurred after initial DFI diagnosis date.

- -

- Associated with a concurrent DFI diagnosis during the same visit to ensure treatment relevance.

2.3.2. Treatment Timing

- -

- Early treatment: initiated within 3 days of first DFI diagnosis;

- -

- Delayed treatment: initiated ≥3 days after first DFI diagnosis;

- -

- No treatment: no documented DFI-specific treatment within the UCSF system.

2.3.3. Treatment Cutoff Validation

The 3-day threshold for early treatment was selected after testing multiple clinically relevant cutoffs and considering real-world clinical workflows. We evaluated cutoff points at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, 30, 45, 60, and 90 days. A 1-day cutoff was not feasible, as no patients in our dataset received treatment on the day of DFI diagnosis, reflecting inherent delays in diagnostic confirmation, culture results, and treatment initiation.

The 2-day cutoff, aligned with IWGDF/IDSA 2023 guidelines, showed significant effects (15.3% absolute difference in hospitalization rates, p = 0.0048, n = 151 early vs. 226 delayed). However, the 3-day cutoff provided superior discrimination (17.9% absolute difference in hospitalization rates, p = 0.0008, n = 163 early vs. 214 delayed) with better sample size balance for valid causal inference. Longer cutoffs remained statistically significant but became less clinically interpretable as the definition of “early” treatment broadened.

The 3-day threshold reflects real-world clinical workflows that extend beyond ideal 48 h intervention timelines, accounting for: (1) diagnostic/culture delays, (2) specialist consultation requirements, (3) differentiation of mild vs. moderate infection severity, (4) weekend and holiday referral bottlenecks, and (5) inclusion of both antibiotic initiation and procedural interventions. Therefore, the 3-day threshold balances guideline-recommended urgency with the statistical power and sample size balance required for robust causal inference in observational data.

2.4. Exposure and Outcome

2.4.1. Exposure

The primary exposure was timing of DFI treatment:

Early: treatment within 3 days of diagnosis;

Delayed/None: treatment ≥ 3 days after diagnosis or no documented treatment.

2.4.2. Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was DFI-related hospitalization occurring on or after treatment (or after diagnosis for untreated patients), defined as inpatient admission (OMOP visit concept IDs 9201, 8717) with validated DFI diagnostic codes. DFI-related hospitalizations were identified using 99 validated OMOP concept IDs covering diabetic foot ulcers, cellulitis, osteomyelitis, gangrene, and related complications. Representative codes included diabetic foot ulcer (4159742), infection of foot due to diabetes mellitus (4171406), cellulitis of foot (4028237), and osteomyelitis of foot (133853). Same-day treatment and hospitalization events were included to capture patients who received treatment after they needed to be immediately admitted to hospital, reflecting either immediate treatment inadequacy or recognition of disease severity during the treatment encounter.

2.4.3. Secondary Clinical Outcome

Lower-extremity amputation served as a secondary clinical endpoint, representing the most severe complication of DFI progression and the ultimate outcome that early treatment aims to prevent. Amputation events were identified using validated diagnostic codes covering major and minor amputations of the foot, ankle, and lower leg occurring after DFI diagnosis. This outcome provides unambiguous clinical meaning that complements our primary hospitalization analysis by capturing irreversible treatment failure rather than care intensity measures.

2.5. Covariates

We adjusted for 19 covariates, including:

- Demographics: age, gender, race (White, Black, Asian, other), Hispanic ethnicity;

- Clinical factors: diabetes type, MRSA colonization status;

- Comorbidities: chronic kidney disease, peripheral neuropathy, peripheral artery disease, osteomyelitis;

- Medications: anti-diabetic medication use, insulin vs. non-insulin classification;

- Laboratory values: albumin, serum creatinine, white blood cell count, hemoglobin A1c.

2.6. Causal Inference Approach

2.6.1. Notation

Following standard causal inference notation:

- A: Binary treatment indicator (A = 1 for early treatment within 3 days; A = 0 for delayed/no treatment);

- W: Vector of baseline covariates including demographics, comorbidities, medications, and laboratory values (19 covariates total);

- Y1: Binary primary outcome indicator (Y1 = 1 for DFI-related hospitalization; Y1 = 0 for no hospitalization);

- Y2: Binary secondary outcome indicator (Y2 = 1 for lower-extremity amputation; Y2 = 0 for no amputation).

2.6.2. Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation (TMLE)

We estimated the causal effect using Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation (TMLE), a doubly robust method that provides consistent estimates when either the outcome model or propensity score model is correctly specified. TMLE combines machine learning with targeted bias reduction through a three-step process:

- Outcome regression modeling: Estimated E[Y|A,W] using SuperLearner to predict outcome probability under both treatment conditions.

- Propensity score estimation: Estimated P(A = 1|W) using SuperLearner to model the probability of receiving early treatment given confounders.

- Targeted updating: Used clever covariates H(A,W) = A/P(A = 1|W) − (1 − A)/P(A = 0|W) to update the outcome model and reduce bias.

The same exposure (A) and covariate set (W) were used for both outcomes, with separate outcome models fitted for hospitalization (Y1) and amputation (Y2) analyses.

2.7. Addressing Baseline Group Differences

The substantial baseline differences between treatment groups represent the core analytical challenge our study addresses. In real-world clinical practice, physicians appropriately triage patients based on disease severity, creating systematic differences between those who receive early versus delayed/no treatment. Rather than viewing these differences as a methodological flaw, we recognized them as evidence of confounding by indication requiring causal methods. Our approach is consistent with the Causal Roadmap framework, which emphasizes that causal effects can still be identified despite baseline imbalance if two conditions are met: (1) a sufficient adjustment set is specified and (2) adequate overlap (positivity) holds (i.e., across covariate patterns, there are patients in both treatment groups for comparison) [23].

To address the first condition, we adjusted for 19 covariates spanning demographics, comorbidities, antidiabetic medication use, and laboratory markers (A1c, WBC, albumin, creatinine), representing clinically relevant factors that influence both treatment selection and outcomes. To address the second, we evaluated propensity score distributions and weight diagnostics, confirming that while overlap was imperfect, probabilities were nonzero across strata (range 0.036–0.423). Only 2% of patients had extreme weights (>10). Because the exposure was the same for both outcomes (early vs. delayed/no treatment), the same adjustment set and overlap diagnostics apply to both the hospitalization and amputation analyses; however, the smaller number of amputation events reduced statistical precision.

We chose Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation (TMLE) because it is designed for exactly this situation. TMLE provides valid causal estimates even when treatment groups differ substantially at baseline by combining two strategies: outcome prediction and treatment assignment modeling (propensity scores). This “double robustness” means estimates remain consistent if either model is correctly specified, and efficiency is achieved when both are well estimated.

Unlike traditional regression methods that may fail with complex data patterns, TMLE maintains valid statistical inference when combined with machine learning approaches, making it particularly well-suited for analyzing observational healthcare data for which treatment assignment reflects clinical judgment rather than randomization.

2.8. Statistical Inference

2.8.1. Estimation and Standard Errors

Standard errors and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using influence curve methodology; p-values were computed using normal approximation with two-sided tests (α = 0.05).

2.8.2. Bootstrap Confidence Intervals

To provide comprehensive statistical inference across all estimation methods, we conducted bootstrap resampling with 500 iterations (B = 500) for both hospitalization and amputation outcomes. Bootstrap samples were drawn with replacement from the original dataset (n = 1434), maintaining the same sample size for each iteration. For each bootstrap sample, we re-estimated treatment effects using all three approaches: simple substitution (G-computation), inverse probability weighting (IPW), and TMLE with the identical SuperLearner ensemble.

Bootstrap confidence intervals were calculated using both normal approximation and quantile methods. The normal approximation method used the bootstrap standard error: CI = point estimate ± 1.96 × SD(bootstrap estimates). The quantile method used the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrap distribution directly. All bootstrap analyses used the same random seed (252) for reproducibility.

2.8.3. Model Diagnostics

Positivity was assessed via propensity score distributions; inverse probability weights >10 were flagged as violations. TMLE estimates were compared with G-computation and IPW for robustness.

2.8.4. SuperLearner Ensemble

Five algorithms were combined with cross-validation-based weighting:

- -

- SL.glm (generalized linear models with all covariates);

- -

- SL.glmnet (elastic net regularization);

- -

- SL.gam (generalized additive models with smooth functions);

- -

- SL.earth (multivariate adaptive regression splines);

- -

- SL.mean (intercept-only baseline model).

2.8.5. Missing Data

Continuous laboratory values were imputed using median values from available observations.

2.8.6. Software

Analyses were conducted in R version 4.5.0 using ltmle and SuperLearner packages, with reproducible random seed (252).

2.9. Subgroup Analyses

Conducted TMLE for clinically relevant subgroups with ≥30 patients:

- -

- Ethnicity: Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic;

- -

- Glycemic control: A1c < 6.5% (good), ≥6.5% (poor), ≥8.0% (very poor);

- -

- Anti-diabetic medication use: taking vs. not taking;

- -

- Laboratory thresholds: WBC > 11.0 K/μL, albumin > 3.5 g/dL.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Treatment Patterns

Among 1434 patients, 163 (11.4%) received early treatment. The remaining 1271 patients (88.6%) received delayed (≥3 days) or no documented treatment and thus comprised the comparison group. Within this group, 214 received delayed treatment, while 1057 had no documented treatment. Treatment delivery patterns varied significantly by clinical setting: emergency department visits comprised 197 (52.3%) of all first treatments, followed by office visits (97 patients, 25.7%) and outpatient clinics (83 patients, 22.0%). Drug therapy accounted for 196 (52.0%) of treatments, while procedures comprised 181 (48.0%).

3.2. Baseline Characteristics and Treatment Selection

Baseline characteristics revealed significant differences between treatment groups, suggesting appropriate clinical triage rather than random allocation (Table 1). These differences validate our causal inference approach, as they represent exactly the type of confounding by indication that TMLE is designed to address. Early-treated patients demonstrated markers of more severe disease:

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of patients with diabetic foot infection by treatment timing groups. Early treatment patients had higher A1C, more frequent MRSA positivity, and greater medication complexity, consistent with appropriate clinical triage of higher-risk patients and reinforcing the role of confounding by indication (* Statistically significant at p < 0.05).

- Higher glycemic dysfunction: A1c levels were significantly elevated (8.43 ± 2.52% vs. 7.75 ± 2.15%, p = 0.002);

- Increased infection risk: MRSA colonization was more than twice as prevalent (10.4% vs. 4.7%, p = 0.004);

- Greater diabetes complexity: Anti-diabetic medication use was nearly universal (93.9% vs. 71.8%, p < 0.001).

Demographic disparities were also evident: Hispanic patients were significantly less likely to receive early treatment (13.5% vs. 21.6%, p = 0.021), suggesting potential inequities in care access or clinical decision-making patterns.

Age, gender distribution, and most comorbidities (chronic kidney disease, neuropathy, peripheral artery disease, osteomyelitis) showed no significant differences between treatment groups. Laboratory markers other than A1c were similar, with albumin (3.13 ± 0.71 vs. 3.18 ± 0.76 g/dL, p = 0.501), serum creatinine (8.22 ± 31.65 vs. 10.47 ± 31.04, p = 0.613), and white blood cell count (6.03 ± 5.72 vs. 6.74 ± 4.85 K/μL, p = 0.108) showing no significant differences among groups.

3.3. Primary Outcomes

Hospitalization rates differed markedly by treatment status. Among early-treated patients, 63.2% were subsequently hospitalized compared to 32.9% of delayed/untreated patients (p < 0.001). Overall, 53.1% of all treated patients experienced hospitalization compared to 30.4% of untreated patients. The median time from treatment to hospitalization was 19 days, with a mean of 195.4 days, indicating both immediate and long-term hospitalization risk.

3.3.1. Causal Effect Estimates

Targeted maximum likelihood estimation revealed a substantial association between early treatment and increased hospitalization risk:

- Risk Difference: 0.293 (95% CI: 0.220–0.367, p < 0.001);

- Risk Ratio: 1.88 (95% CI: 1.72–2.09).

This data indicates that early treatment was associated with a 29.3 percentage point increase in absolute hospitalization risk and an 88% relative increase compared to delayed/no treatment.

3.3.2. Robustness Across Methods

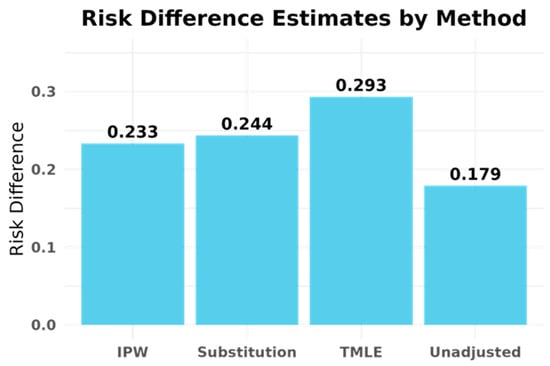

Alternative causal inference approaches yielded consistent directional findings:

- G-computation: Risk difference = 0.244;

- Inverse probability weighting: Risk difference = 0.233.

The consistency across estimation methods supports the robustness of our findings and suggests that the observed association is not an artifact of a particular modeling approach.

3.3.3. Sensitivity and Validation Analyses

Sensitivity Analysis

The consistency of findings across G-computation, IPW, and TMLE provides evidence against major model misspecification. However, the substantial baseline differences between treatment groups and the counterintuitive direction of effects strongly suggest residual confounding by unmeasured disease severity indicators. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Risk difference estimates for hospitalization outcome by G-computation, inverse probability weighting (IPW), and targeted maximum likelihood estimation (TMLE). All three methods show consistent increases in hospitalization risk among patients receiving early UCSF treatment, suggesting that the apparent harm reflects confounding by indication and fragmented care rather than true treatment harm.

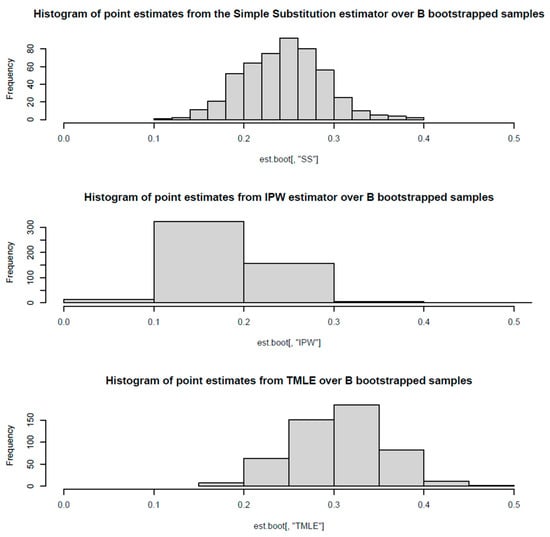

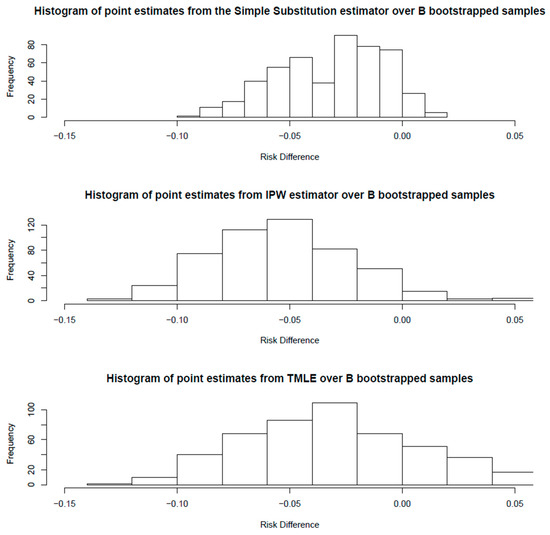

Bootstrap Validation

Bootstrap resampling (B = 500) confirmed the robustness of our TMLE estimates and provided alternative confidence interval estimates. The bootstrap distributions showed:

- Simple Substitution: Mean bootstrap estimate = 0.244 (range: 0.116–0.387);

- IPW: Mean bootstrap estimate = 0.181 (range: 0.072–0.938);

- TMLE: Mean bootstrap estimate = 0.306 (range: 0.162–0.452).

Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for the risk difference were:

- Simple Substitution: 15.5–33.2% (normal), 15.7–33.8% (quantile);

- IPW: 11.5–35.2% (normal), 9.9–27.1% (quantile);

- TMLE: 19.6–39.1% (normal approximation), 20.5–39.6% (quantile method).

The TMLE bootstrap confidence intervals (20.5–39.6%) were consistent with our influence curve-based intervals (22.0–36.7%), confirming the validity of our primary analysis. The confidence intervals for IPW showed greater variability between methods (9.9–27.1% quantile vs. 11.5–35.2% normal approximation), while TMLE demonstrated superior precision and stability across bootstrap samples. See Figure 2 and Table 2.

Figure 2.

Bootstrap distribution of treatment effect estimates for hospitalization outcome. Bootstrap resampling across 500 iterations confirmed consistent protective directions for early treatment across all three estimation methods, though confidence intervals crossed zero. The stability of negative point estimates reinforces that the protective signal is systematic rather than an artifact of particular modeling choices, though limited statistical power prevents definitive conclusions.

Table 2.

Hospitalization Outcomes by treatment timing across three causal inference approaches (G-computation, IPW, TMLE) with bootstrap confidence intervals. Across all methods, early treatment was associated with increased hospitalization risk, an association likely reflecting confounding by indication and exposure misclassification rather than true treatment harm.

3.3.4. Effect Modification Analysis

Subgroup analyses revealed substantial heterogeneity in treatment effects across patient populations.

Glycemic Control Status

The most striking finding was complete effect modification by baseline diabetes control:

- Good control (A1c < 6.5%): No significant association (RD = 0.08, 95% CI: −0.11–0.27, p = 0.40);

- Poor control (A1c ≥ 6.5%): Strong association (RD = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.27–0.43, p < 0.001);

- Very poor control (A1c ≥ 8.0%): Moderate association (RD = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.16–0.42, p < 0.001).

Ethnic Disparities

Hispanic patients showed nearly twice the effect magnitude of non-Hispanic patients:

- Hispanic: RD = 0.43 (95% CI: 0.30–0.56, p < 0.001);

- Non-Hispanic: RD = 0.26 (95% CI: 0.18–0.35, p < 0.001).

Medication Use Patterns

Patients not taking anti-diabetic medications demonstrated larger treatment effects:

- Not on medications: RD = 0.34 (95% CI: 0.22–0.46, p < 0.001);

- Taking medications: RD = 0.23 (95% CI: 0.16–0.31, p < 0.001).

Laboratory Markers

Interestingly, traditional infection markers showed paradoxical patterns:

- Elevated WBC (>11.0 K/μL): No significant association (RD = 0.14, 95% CI: −0.06–0.33, p = 0.16);

- Normal/low WBC (≤11.0): Strong association (RD = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.22–0.39, p < 0.001).

Similarly, albumin levels showed unexpected patterns:

- High albumin (>3.5 g/dL): Moderate association (RD = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.08–0.41, p = 0.004);

- Normal/low albumin (≤3.5): Strong association (RD = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.24–0.39, p < 0.001).

3.3.5. Model Performance and Diagnostics

Propensity Score Assessment

Propensity score distributions demonstrated adequate but imperfect overlap between treatment groups:

- Mean propensity scores: 0.151 for early-treated vs. 0.109 for delayed/untreated patients;

- Range: 0.036 to 0.423, indicating reasonable but not complete overlap;

- Positivity concerns: 573 patients (40.0%) had propensity scores below 0.1, suggesting limited comparability between groups and potentially reduced precision, particularly in subgroup analyses.

Weight Distribution

Inverse probability weights showed generally well-balanced treatment groups:

- Mean absolute weight: 1.89;

- Maximum weight: 23.4;

- Extreme weights (>10): 28 patients (2.0% of sample).

The relatively low proportion of extreme weights suggests adequate positivity for most analyses, though some precision loss in subgroup analyses is expected.

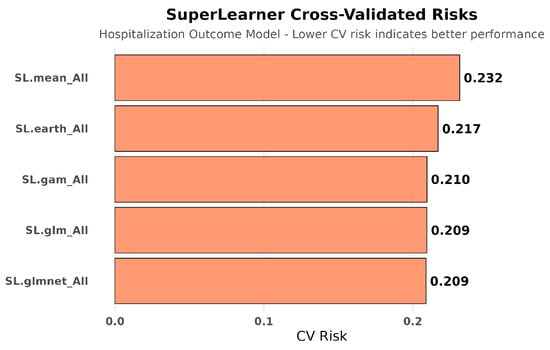

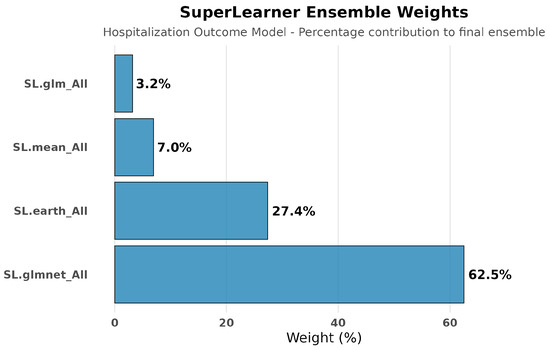

SuperLearner Performance

Hospitalization Outcome Models: Cross-validated ensemble selection demonstrated the value of machine learning approaches over traditional parametric methods. The optimal ensemble heavily weighted regularized regression (SL.glmnet: 62.5%) and multivariate adaptive regression splines (SL.earth: 27.4%), with minimal contribution from simple approaches (SL.mean: 7.0%, SL.glm: 2.0%). See Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 3.

SuperLearner cross-validated risks for hospitalization outcome modeling. Ensemble machine learning methods (SL.glmnet, SL.earth) substantially outperformed simple regression approaches for predicting hospitalization, revealing complex non-linear relationships between covariates and outcomes. This complexity underscores why sophisticated causal methods are necessary but insufficient when datasets are fundamentally incomplete.

Figure 4.

SuperLearner ensemble weights for hospitalization outcome modeling. The ensemble assigned dominant weight to regularized regression (Sl.glmnet: 62.5%) and multivariate adaptive regression splines (Sl.earth: 27.4%), with minimal contribution from simple linear models (SL.glm: 2.0%). This distribution indicates that hospitalization outcomes depend on complex non-linear interactions between clinical, demographic, and laboratory factors that simple regression approaches would miss.

Cross-validated risk assessment confirmed superior performance of ensemble methods:

- Best performing: SL.glmnet (risk = 0.209) and SL.glm (risk = 0.209);

- Flexible modeling: SL.gam (risk = 0.210) and SL.earth (risk = 0.217);

- Baseline: SL.mean (risk = 0.232).

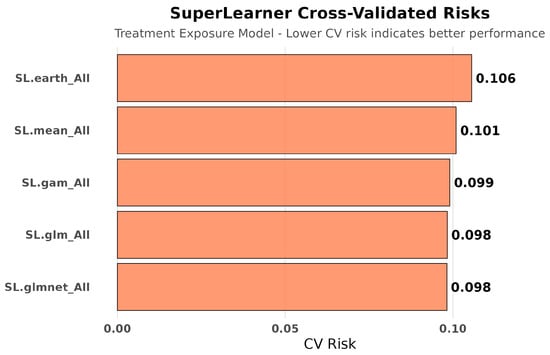

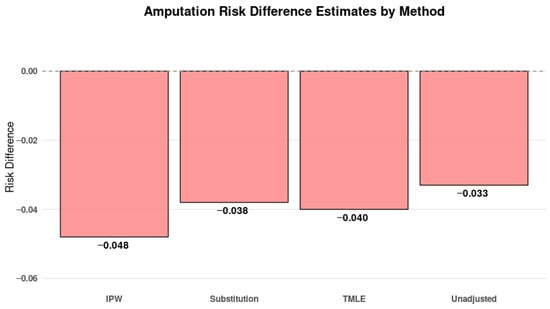

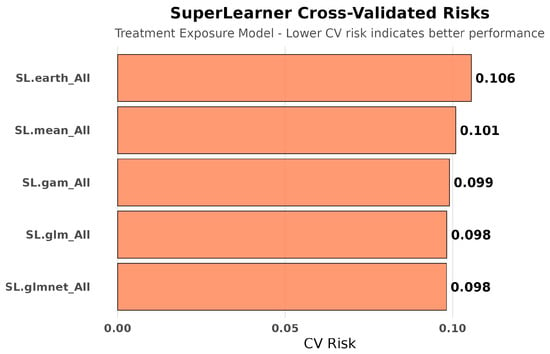

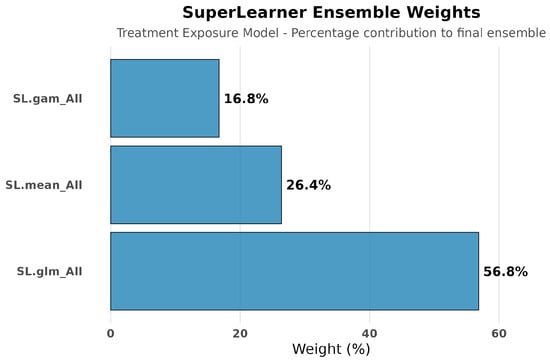

Treatment Exposure Models: Treatment exposure modeling achieved consistent performance across algorithms (CV risks: 0.098–0.106), with the ensemble weighting SL.glm (56.8%), SL.mean (26.4%), and SL.gam (16.8%), indicating stable propensity score estimation across different modeling approaches. See Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 5.

SuperLearner cross-validated risks for treatment exposure modeling. Treatment assignment was predicted with stable accuracy across algorithms, showing smaller cross-validated risk variation than hospitalization outcomes. This stability suggests treatment selection followed more consistent clinical decision patterns compared to the multifactorial nature of hospitalization outcomes.

Figure 6.

SuperLearner ensemble weights for treatment exposure modeling. Weights were distributed across SL.glm (56.8%), SL.mean (26.4%), and SL.gam (16.8%), indicating balanced contributions and stable performance in modeling treatment assignment. Unlike hospitalization, exposure modeling did not require complex non-linear methods, reflecting more predictable treatment selection patterns.

The dominance of regularized and flexible modeling approaches for hospitalization outcomes indicates substantial non-linear relationships and variable interactions that conventional regression methods would miss. On the other hand, the consistency in exposure modeling suggests robust treatment assignment prediction.

3.4. Secondary Clinical Outcomes: Lower-Extremity Amputation

Among 1434 patients, 227 (15.8%) experienced lower-extremity amputation following DFI diagnosis. Amputation patterns differed markedly from hospitalization outcomes, revealing the clinical complexity underlying treatment selection.

3.4.1. Causal Effect Estimates

Unadjusted Analysis: Early-treated patients demonstrated lower amputation rates (12.9%, 21/163) compared to delayed/untreated patients (16.2%, 206/1271), yielding an unadjusted risk difference of −3.3% (95% CI: −8.9% to 2.2%, p = 0.24).

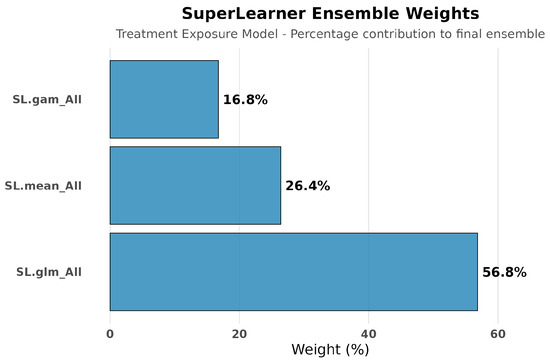

Causal Effect Estimates: All three causal inference methods demonstrated consistent protective directions. See Figure 7:

Figure 7.

Risk difference estimates for amputation outcome by G-computation, IPW, and TMLE. All methods showed point estimates trending toward a protective effect for early treatment, aligning with clinical expectations that timely intervention prevents irreversible complications. However, confidence intervals cross zero, reflecting limited statistical power in this outcome.

Simple Substitution: RD = −0.038

IPW: RD = −0.048

TMLE: RD = −0.040

3.4.2. Sensitivity and Validation Analyses

Bootstrap validation (B = 500) confirmed robustness across estimation approaches; quantile-based confidence intervals were: SS [−7.9%, 0.4%], IPW [−10.7%, 1.1%], and TMLE [−9.8%, 6.6%]. See Figure 8 and Table 3.

Figure 8.

Amputation outcomes by treatment timing across three causal inference approaches (G-computation, IPW, TMLE) with bootstrap confidence intervals. All methods showed point estimates suggesting a protective effect for early treatment, aligning with clinical expectations that timely intervention prevents irreversible complications, though confidence intervals crossed zero due to limited statistical power.

Table 3.

Amputation Outcome Bootstrap Confidence Intervals for Treatment Effect Estimates: All three methods consistently suggested a protective effect of early treatment on amputation risk (absolute risk reductions 3.8–4.8%), though confidence intervals included zero. This consistent protective direction across bootstrap iterations and multiple estimation approaches supports the interpretation that early treatment may prevent irreversible complications despite increasing short-term healthcare utilization.

3.4.3. Super Learner Performance for Amputation

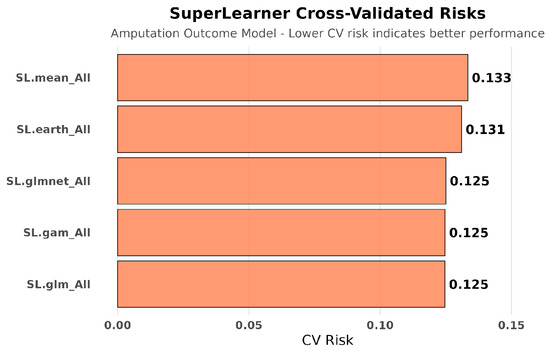

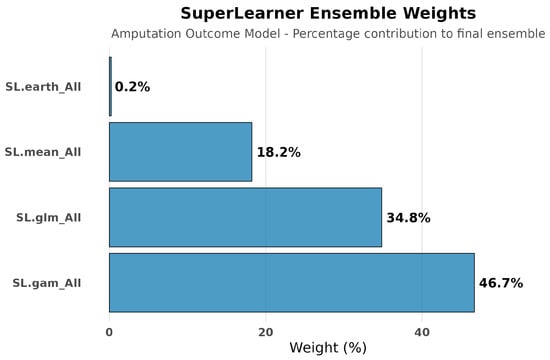

Cross-validated risk assessment for amputation outcomes revealed superior performance of simple parametric methods (SL.glm and SL.gam: 0.125) compared to complex approaches (SL.mean: 0.133, SL.earth: 0.131). The ensemble weighed SL.gam (46.7%), SL.glm (34.8%), and SL.mean (18.2%), contrasting with hospitalization models where ensemble methods dominated. See Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 9.

SuperLearner cross-validated risks for amputation outcome modeling. For amputation outcomes, simpler parametric models (SL.glm, SL.gam) achieved the lowest cross-validated risks, outperforming more flexible models. This outcome indicates that amputation risk was more straightforward to predict than hospitalization, aligning with role as a definitive clinical endpoint.

Figure 10.

SuperLearner ensemble weights for amputation outcome modeling. The ensemble weighted SL.gam (46.7%) and SL.glm (34.8%) most heavily, contrasting with hospitalization outcomes where complex machine learning models dominated. This reflects the more predictable and direct determinants of amputation risk compared to the multifactorial influences on hospitalization decisions.

Figure 11.

SuperLearner cross-validated risks for treatment exposure modeling (amputation analysis). Exposure prediction risks for amputation analyses were stable across algorithms, similar to hospitalization exposure models. This stability confirms that treatment assignment was consistently modeled regardless of the clinical outcome studied.

Figure 12.

SuperLearner ensemble weights for treatment exposure modeling. Treatment exposure modeling for amputation analyses replicated the balanced weight distribution observed in hospitalization analyses (distributed across SL.glm, Sl.mean, and SL.gam). This consistency across outcome analyses demonstrates that treatment assignment patterns were robustly captured regardless of which clinical endpoint was being studied.

3.4.4. Clinical Interpretation

The opposing directions of treatment effects—increased hospital risk cast against decreased amputation risk—provide critical insight into DFI care patterns. This paradox likely reflects appropriate clinical triage: providers correctly identify high-risk patients for immediate intervention, leading to increased short-term healthcare utilization (e.g., IV antibiotics and surgical procedures) while potentially preventing irreversible complications (e.g., amputations). These findings frame the central interpretive challenge of our study.

4. Discussion

Our findings challenge conventional assumptions about early DFI treatment, though they must be interpreted cautiously given substantial exposure misclassification. The apparent increase in hospitalization risk reflects confounding by indication and incomplete capture of external care rather than true treatment harm, consistent with paradox outlined in Section 3.4.4.

4.1. External Care and Exposure Misclassification

With 73.7% of DFI patients having no documented treatment within UCSF, a substantial proportion of treatment likely occurred via external providers not captured in the UCSF EHR system. This finding indicates substantial exposure misclassification due to fragmented healthcare data, an issue explored further in the Limitations section. This pattern is not a minor limitation but the central lesson of our analysis: single-institution studies are fundamentally compromised by healthcare fragmentation. Sophisticated causal methods such as TMLE succeed primarily by revealing these biases, not by resolving them.

4.2. Confounding by Indication: Why Increased Hospitalization Does Not Mean Treatment Harm

The 29.3% point increase in hospitalization risk associated with early treatment does not indicate that early intervention causes harm. Instead, it reflects appropriate clinical triage combined with systematic exposure misclassification. This distinction is critical for interpreting our findings correctly.

Rather than representing a methodological flaw, the substantial baseline differences between our treatment groups actually validate our clinical interpretation. Early-treated patients had significantly elevated hemoglobin A1c levels (8.43% vs. 7.75%, p = 0.002), more than double the rate of MRSA colonization (10.4% vs. 4.7%, p = 0.004), and nearly universal anti-diabetic medication use (93.9% vs. 71.8%, p < 0.001). These differences demonstrate that clinicians appropriately identified and prioritized high-risk patients for immediate intervention based on disease severity markers. The sickest patients—those most likely to require hospitalization regardless of treatment timing—were systematically selected for early treatment through sound clinical judgment.

This creates the appearance of treatment harm in observational data: the patients receiving early treatment have worse outcomes (more hospitalizations) not because the treatment failed, but because they were sicker to begin with. This is exactly the type of “confounding by indication” that makes observational studies misleading when analyzed with traditional methods. Without causal inference techniques, one might incorrectly conclude that early treatment should be avoided, when in fact it represents appropriate care for high-risk patients that may prevent worse long-term outcomes such as amputation.

As detailed in Section 2.7, causal methods such as TMLE can adjust for measured confounding by indication. However, they cannot overcome exposure misclassification from incomplete treatment capture (Section 4.1 and Section 4.6.1), which likely explains the counterintuitive direction and magnitude of our hospitalization findings. The baseline differences we observe validate rather than undermine our causal inference approach; they demonstrate that the treatment assignment mechanism we are striving to model is real and clinically meaningful.

4.3. Effect Modification Reveals Clinical Complexity

Our subgroup analyses uncovered striking heterogeneity that provides important insights into both the underlying confounding mechanisms and potential clinical applications. Most notably, patients with good glycemic control (A1c < 6.5%) showed no significant association between treatment timing and hospitalization (RD = 0.08, p = 0.40), while those with poor control demonstrated strong associations (RD = 0.35, p < 0.001). This finding suggests that glycemic control may serve as both a confounding variable and an effect modifier—patients with well-controlled diabetes may be less susceptible to the selection biases that affect treatment decisions for those with poorly controlled disease.

The nearly two-fold difference in effect size between Hispanic (RD = 0.43) and non-Hispanic patients (RD = 0.26) raises important concerns about healthcare equity. Given that Hispanic patients were significantly less likely to receive early treatment (13.5% vs. 21.6%, p = 0.021), this finding might reflect differential care access, provider decision-making patterns, or cultural factors affecting healthcare utilization. The larger effect size among Hispanic patients could indicate either more severe disease presentation when care is finally sought or systematic differences in the quality or timeliness of care received.

Paradoxically, traditional infection markers showed unexpected patterns: patients with elevated white blood cell counts (>11.0 K/μL) showed no significant treatment timing effects (p = 0.16), while those with normal or low counts demonstrated strong associations. This counterintuitive finding challenges conventional clinical assumptions and suggests that readily observable laboratory markers might not capture the complexity of infection severity or treatment selection mechanisms in real-world practice.

4.4. Divergent Clinical Outcomes (Hospitalization vs. Amputation)

The contrast between hospitalization and amputation outcomes reinforces the paradox described in Section 3.4.4. Early intervention appears to increase short-term utilization while reducing the risk of irreversible complications, a pattern that aligns with established DFI management principles and validates our causal inference approach.

The contrasting SuperLearner performance patterns between outcomes provide additional clinical insights. Hospitalization predictions required complex ensemble methods (SL.glmnet dominance), suggesting intricate interactions between clinical factors, care processes, and utilization decisions. On the other hand, simple parametric models (SL.glm and SL.gam) performed best in amputation predictions, indicating more straightforward risk relationships based on baseline patient characteristics. This divergence supports our interpretation that hospitalization reflects complex care intensity decisions while amputation represents more predictable clinical outcomes.

While amputation represents an unambiguous clinical endpoint, the non-significant result (p = 0.126) reflects reduced statistical power due to lower event rates (15.8% vs. 36.3%). The consistent protective direction across all estimation methods and robust bootstrap validation strengthen confidence in the clinical interpretation despite the lack of statistical significance. Future studies with larger sample sizes or longer follow-up periods might be needed to definitively establish protective effects against severe complications.

4.5. Implications for Clinical Decision Support and EHR-Based Research

Our results have immediate implications for the design and implementation of clinical decision support systems. Many existing tools rely on descriptive EHR variables—laboratory values, medication histories, diagnostic codes—to guide treatment recommendations. However, these variables often serve as proxies for disease severity rather than true confounders, leading to systematically biased treatment effect estimates when used in predictive models that do not factor in causal considerations.

The SuperLearner ensemble results reinforce this point: regularized regression methods (SL.glmnet) dominated the optimal ensemble (62.5%), with substantial contributions from flexible modeling approaches (SL.earth: 27.4%); simple parametric methods contributed minimally (SL.glm: 2.0%). This pattern indicates complex, non-linear relationships between confounders and outcomes that conventional regression approaches would miss.

More broadly, our study demonstrates how sophisticated causal inference methods can reveal hidden biases in observational healthcare data that might otherwise lead to incorrect clinical conclusions. The consistency of our findings across multiple estimation approaches (TMLE, G-computation, IPW) provides confidence in the robustness of our results and suggests that the observed associations reflect genuine confounding patterns rather than methodological artifacts. At the same time, these findings highlight the need to redesign clinical decision support systems around causal rather than purely predictive frameworks. Predictive-only systems trained on observational associations would systematically misinterpret early treatment as harmful and could discourage appropriate care. In contrast, causally informed systems would recognize that early intervention may appropriately increase short-term healthcare utilization while preventing irreversible complications such as amputation; they thereby would help align recommendations with clinical judgment and patient benefit.

4.6. Limitations

While our study employed rigorous causal inference methods and comprehensive data processing, several important limitations should be acknowledged:

4.6.1. Data Completeness and External Validity

As discussed in Section 4.1, the apparent harm from early treatment primarily reflects exposure misclassification from external care—a pattern we emphasize not simply as a limitation but as our primary finding about the challenges of single-institution causal inference in fragmented healthcare systems. With 73.7% of DFI patients having no documented treatment within UCSF, the majority likely received care at external providers—community clinics, urgent care centers, other hospital systems, or private practices—suggesting data that was not captured in the UCSF EHR system. This conundrum creates systematic exposure misclassification, through which patients classified as being “untreated” or getting “delayed treatment” might actually have received prompt, appropriate care elsewhere.

This limitation is particularly problematic for DFI management, because patients often establish care with podiatrists, wound care specialists, or community providers who might not be affiliated with academic medical centers. Additionally, patients might seek initial treatment at geographically convenient locations (e.g., neighborhood urgent care) before being referred to UCSF for specialized or complicated care. The 11.4% early treatment rate we observed likely represents only the most severe cases requiring immediate tertiary care, creating a highly selected sample that systematically over represents complex, high-risk patients in the “early treatment” group.

Differential care-seeking patterns may further compound this bias. Patients with better-controlled diabetes, higher health literacy, or established primary care relationships might be more likely to receive timely treatment in community settings, while those with poor diabetes control, limited healthcare access, or acute presentations might be more likely to present to UCSF emergency departments. This pattern would systematically assign sicker patients to the “early treatment” group within our dataset while misclassifying healthier patients who received appropriate external care as “untreated.”

We considered restricting analysis to only documented treatments (n = 377:163 early, 214 delayed), which would eliminate exposure misclassification but at significant cost. This restriction would remove 73.7% of the cohort and any comparison to usual care patterns, creating extreme selection bias by analyzing only patients requiring tertiary care documentation. Our decision to include all DFI patients, despite incomplete treatment capture, better represents the fragmented healthcare delivery patterns that constitute the core methodological challenge this study addresses.

Geographic and institutional specificity may limit generalizability. UCSF serves a unique patient population in the San Francisco Bay Area, with specific demographic characteristics, insurance patterns, and care delivery models that might not represent other healthcare systems or regions. The observed disparities in care access and treatment patterns might be particularly influenced by local healthcare infrastructure and regional practice variations.

4.6.2. Clinical Severity Assessment

Absence of structured severity measures represents a critical gap in our confounding adjustment strategy. Standard diabetic foot assessment tools such as the PEDIS (Perfusion, Extent, Depth, Infection, Sensation) classification system, Wagner grades, or University of Texas wound classification were not available in structured format. These validated severity measures are routinely used in clinical practice to guide treatment decisions and would provide more precise confounding adjustment than the laboratory and demographic variables we employed.

Missing wound characteristics further limit our ability to assess disease severity. Important clinical factors such as wound size, depth, location, presence of exposed bone or tendon, and signs of systemic toxicity are critical determinants of both treatment urgency and prognosis but were not captured in our structured data extraction.

Provider clinical judgment remains unmeasured despite being a primary driver of treatment decisions. Experienced clinicians integrate multiple factors—patient appearance, vital signs, pain levels, functional status, social circumstances—that are not readily captured in structured EHR data but substantially influence treatment timing and intensity. Future work should integrate structured severity scores into EHR system and leverage natural language processing to extract wound characteristics from free-text notes, thereby improving confounding adjustment for causal inference.

4.6.3. Methodological Constraints

Positivity violations affected precision in some subgroup analyses. While overall propensity score overlap was adequate (range: 0.036–0.423), 40% of patients had scores below 0.1, and 2% had extreme weights exceeding 10. These violations were particularly concerning in the Hispanic subgroup, where 65% of patients had scores below 0.1, suggesting limited overlap in covariate distributions that might affect the interpretability of effect estimates.

Temporal confounding remains possible despite our careful attention to treatment timing. The 3-day cutoff for early treatment, while clinically motivated, might not capture the optimal treatment window for all patients or clinical presentations. Additionally, the exact timing of symptom onset relative to diagnosis was not available, potentially leading to a misidentification of some patients’ true treatment delays.

4.6.4. Measurement and Classification Issues

Laboratory value imputation using median values might not fully capture the clinical significance of missing data. Missing laboratory values might themselves indicate patient severity, care patterns, or clinical decision-making processes that are relevant to outcomes but not captured by simple imputation methods.

Treatment heterogeneity within our broad categories of “antibiotics” and “procedures” likely obscures important differences in treatment intensity, appropriateness, and effectiveness. A single oral antibiotic prescription and an intensive intravenous antibiotic regimen were classified identically, despite representing substantially different clinical interventions.

4.7. A Cautionary Tale for Healthcare Analytics

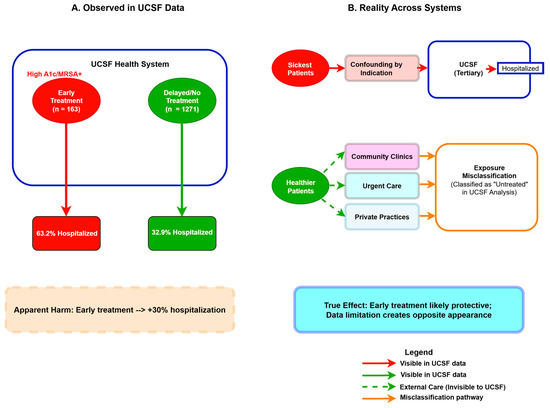

Our study underscores a broader lesson introduced in Section 4.1: even sophisticated causal methods cannot overcome fragmented data. The consistency across three causal inference approaches (TMLE, IPW, and G-computation) revealed systematic rather than random bias, though none could eliminate it given the fundamental incompleteness of single-institution data. Until healthcare achieves interoperable EHR systems, single-institution analyses will remain vulnerable to misinterpretation. See Figure 13.

Figure 13.

The Fragmented Care Paradox in Single-Institution Analyses. (A) UCSF data show early treatment associated with increased hospitalization (63.2% vs. 32.9%). (B) Reality across fragmented healthcare systems: sickest patients (red pathway) receive early treatment at UCSF, while healthier patients receive early treatment at external providers (green dashed pathways) and are misclassified as “untreated” in UCSF records. Solid lines represent observable pathways; dashed lines represent external care invisible to institutional data. This combination of confounding by indication and exposure misclassification creates apparent harm when treatment is likely protective.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Overall Findings

In our UCSF cohort, early treatment of diabetic foot infections (DFIs) was associated with increased hospitalization but a protective signal against amputation. As emphasized in Section 4.1, these paradoxical findings reflect appropriate clinical triage compounded by exposure misclassification, rather than true treatment harm. While causal ML revealed that the apparent harm reflects bias rather than effect, the need for sophisticated methods to make this distinction—and their ultimate inability to resolve it—illustrates the cautionary tale: single-institution observational analyses remain vulnerable to misinterpretation when healthcare data are fragmented.

5.2. Future Research Imperatives

Future research should address these challenges in several ways. First, incorporating standardized severity scores (e.g., PEDIS, Wagner) would allow more precise causal comparisons and facilitate stratified analyses. Second, leveraging multicenter or unified EHR datasets could mitigate exposure misclassification and improve generalizability across institutions. Third, future research should extend this work by developing clinical decision support systems (as discussed in Section 4.5) that are grounded in causal inference principles rather than purely predictive frameworks. Finally, validation across diverse patient populations is essential, particularly because our findings suggest potential disparities in access to early treatment and in the magnitude of observed effects among Hispanic patients.

5.3. Final Perspective

Until healthcare systems achieve integration across care settings, observational studies of treatment effectiveness will remain vulnerable to misinterpretation. By treating exposure misclassification and confounding by indication as detectable patterns rather than insurmountable flaws, we demonstrate how causal ML can inform the design of future studies and the development of clinical decision support tools that are more robust to the realities of fragmented healthcare data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.H. and R.R.; methodology, R.H.; software, R.H.; validation, R.H. and R.R.; formal analysis, R.H. and R.R.; investigation, R.H.; resources, R.R.; data curation, R.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H.; writing—review and editing, R.H. and R.R.; visualization, R.H.; supervision, R.R.; project administration, R.H. and R.R.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it involved analysis of de-identified electronic health record data and met the criteria for research not requiring IRB approval under UCSF policies for medical record review using de-identified data (https://irb.ucsf.edu/medical-record-review#irb-review-is-not-required-for-some-research-using-de-identified-or-coded-data (accessed on 15 August 2025)).

Informed Consent Statement

Our study did not require consent from human participants because it was a data only, observational study.

Data Availability Statement

The de-identified electronic health record data that support the findings of this study are available from the University of California, San Francisco, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data due to patient privacy protections and are not publicly available. Data may be available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the University of California, San Francisco, subject to appropriate data use agreements and ethical approval.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DFI | Diabetic foot infection |

| TMLE | Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation |

| EHR | Electronic health record |

| UCSF | University of California, San Francisco |

| OMOP | Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership |

| LEA | Lower extremity amputation |

| IPW | Inverse probability weighting |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| A1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| WBC | White blood cell |

| PEDIS | Perfusion, Extent, Depth, Infection, Sensation |

References

- Waibel, F.W.A.; Uckay, I.; Soldevila-Boixader, L.; Sydler, C.; Gariani, K. Current knowledge of morbidities and direct costs related to diabetic foot disorders: A literature review. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1323315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincke, B.G.; Miller, D.R.; Turpin, R. A classification of diabetic foot infections using ICD-9-CM codes: Application to a large computerized medical database. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frykberg, R.G.; Wittmayer, B.; Zgonis, T. Surgical management of diabetic foot infections and osteomyelitis. Clin. Podiatr. Med. Surg. 2007, 24, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathnayake, A.; Saboo, A.; Malabu, U.H.; Falhammar, H. Lower extremity amputations and long-term outcomes in diabetic foot ulcers: A systematic review. World J. Diabetes 2020, 11, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Primadhi, R.A.; Septrina, R.; Hapsari, P.; Kusumawati, M. Amputation in diabetic foot ulcer: A treatment dilemma. World J. Orthop. 2023, 14, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossel, A.; Lebowitz, D.; Gariani, K.; Abbas, M.; Kressmann, B.; Assal, M.; Uçkay, I. Stopping antibiotics after surgical amputation in diabetic foot and ankle infections—A daily practice cohort. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2019, 2, e00059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, A.J.; Vileikyte, L.; Ragnarson-Tennvall, G.; Apelqvist, J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet 2005, 366, 1719–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Thomas, G.N.; Gill, P.; Torella, F. The prevalence of major lower limb amputation in the diabetic and non-diabetic population of England 2003–2013. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2016, 13, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prompers, L.; Huijberts, M.; Schaper, N.; Apelqvist, J.; Bakker, K.; Edmonds, M.; Holstein, P.; Jude, E.; Jirkovska, A.; Mauricio, D.; et al. Resource utilisation and costs associated with the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Prospective data from the Eurodiale Study. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 1826–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, M.; Rayman, G.; Jeffcoate, W.J. Cost of diabetic foot disease to the National Health Service in England. Diabetes Med. 2014, 31, 1498–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Swerdlow, M.A.; Armstrong, A.A.; Conte, M.S.; Padula, W.V.; Bus, S.A. Five year mortality and direct costs of care for people with diabetic foot complications are comparable to cancer. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2020, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, C.M.; Sugita, T.H.; Rosa, M.Q.M.; Pedrosa, H.C.; Rosa, R.D.S.; Bahia, L.R. Annual direct medical costs of diabetic foot disease in Brazil: A cost of illness study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wukich, D.K.; Ahn, J.; Raspovic, K.M.; Gottschalk, F.A.; La Fontaine, J.; Lavery, L.A. Comparison of transtibial amputations in diabetic patients with and without end-stage renal disease. Foot Ankle Int. 2017, 38, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Tan, T.W.; Boulton, A.J.; Bus, S.A. Diabetic foot ulcers: A review. JAMA 2017, 318, 2053–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrepnek, G.H.; Mills, J.L., Sr.; Lavery, L.A.; Armstrong, D.G. Health Care Service and Outcomes Among an Estimated 6.7 Million Ambulatory Care Diabetic Foot Cases in the U.S. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1278–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, C.W.; Selvarajah, S.; Mathioudakis, N.; Sherman, R.E.; Hines, K.F.; Black, J.H.; Abularrage, C.J. Burden of Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcers on Hospital Admissions and Costs. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 33, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. In 2007. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 596–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-W.; Yang, H.-M.; Hung, S.-Y.; Chen, I.-W.; Huang, Y.-Y. The Analysis for Time of Referral to a Medical Center among Patients with Diabetic Foot Infection. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, M.J.; Rose, S. Targeted Learning: Causal Inference for Observational and Experimental Data; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.L.; Porter, K.E.; Gruber, S.; Wang, Y.; van der Laan, M.J. Diagnosing and responding to violations in the positivity assumption. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2012, 21, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, M.J.; Polley, E.C.; Hubbard, A.E. Super Learner. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2007, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, M.L.; van der Laan, M.J. Causal Models and Learning from Data: Integrating Causal Modeling and Statistical Estimation. Epidemiology 2014, 25, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).