Abstract

Mastectomy, while a life-saving intervention for breast cancer, often leads to profound psychological and emotional challenges for affected women. Feelings of loss altered body image, and anxiety about recurrence can significantly impact mental well-being. This study aimed to explore and describe the experiences of women after mastectomy at Mankweng Tertiary Hospital in Limpopo Province, South Africa. In this study, a qualitative phenomenological design was used. Data were collected through semi-structured in-depth interviews with women who had undergone mastectomy. Fifteen participants were purposively sampled, and thematic analysis was used to identify key patterns and meanings in their narratives. The findings revealed that the participants initially described feelings of being ‘disabled’, incomplete, and anxious about cancer recurrence or their ability to perform maternal functions such as breastfeeding. However, over time, many developed resilience and acceptance, seeing surgery as a life-saving measure and an opportunity for renewal. The adjustment of women after mastectomy is a complicated emotional transition from crisis and loss to adjustment and empowerment. The results identify the need for holistic psychosocial support that combines counseling, peer networks, and education for their family members addressing their emotional healing, body image, and social reintegration.

1. Introduction

Mastectomy is a surgical intervention in which part or all or both of one or both breasts are removed. Mastectomy is most often performed as an intervention for breast cancer or, in some cases, for reduction of risk in women with genetic predisposition to breast cancer [1]. Mastectomy is classified as simple (total) mastectomy, which involves the removal of all breast tissues, or one of the other more complicated mastectomy variants, which includes modified radical mastectomy or bilateral mastectomy, depending on the extent and stage of breast cancer [2]. Mastectomy is a lifesaving procedure and potentially a prophylactic method but is more than simply a biomedical intervention as it goes beyond touching the personal, emotional, and social intersections in a woman’s life. Mastectomy results in physical disfigurement, loss of feeling, and scars that are seen, all of which can significantly alter a woman’s body image and self-identity [3,4]. Breasts are a symbol of femininity, sexuality, and motherhood in many cultures; the loss of the breast often brings mixed feelings of loss and grief and reshapes self-identity [5,6]. Therefore, mastectomy is more than a surgical procedure; it is a psychosocial milestone that requires profound psychological adjustment.

The psychological effects of mastectomy are well understood and include multiple emotional reactions that include anxiety, depression, fear of recurrence, and issues related to self-esteem [7,8]. The literature indicates that women who have had a total mastectomy experience higher psychological distress than women who have had breast conserving surgery [9,10]. For example, in a longitudinal cohort study of postmastectomy women, 48% of the participants experienced moderate to severe depression within the first six months after surgery [11]. This dysphoria can be compounded by sudden physical changes, and loss of femininity can result in feelings of shame and social isolation [12]. Furthermore, postoperative challenges, for example, pain, reduced mobility, and the need for ongoing follow-up with health care, can cause feelings of emotional distress to be exacerbated after surgery [13,14]. In addition, these affective responses are not always temporary; in some cases, a woman’s psychological distress will last for years; consuming them with their relationship, sense of normalcy, and ability to fully engage and be present in their life [15,16].

One of the most significant repercussions of mastectomy is the alteration of body image and the reconstruction of self-identity. The breast is deeply enmeshed in cultural and personal notions of beauty, sexuality, and womanhood [17,18]. Qualitative research has shown that women frequently characterize their postmastectomy experiences as ‘loss of wholeness’ or ‘body fragmentation’, where lack of a breast physically represents a loss of previously coherent self-identity [5,6]. For example, women in a photovoice study conducted in Turkey used metaphors such as ‘emptiness’ and ‘broken mirror’ to describe their bodies post-surgery [5]. Similarly, participants in Sweden reported the need to renegotiate their femininity and regain self-worth after mastectomy [4]. These narratives underscore the intersection of cultural, relational, and psychological processes in shaping how women internalize bodily changes. The process of redefining self thus involves both mourning the lost body part and reimagining a new, resilient identity capable of integrating the surgical experience [3,12].

Emotional adaptation after mastectomy is a multifaceted process influenced by individual resilience, social support, and cultural context. Women often employ coping strategies such as positive reframing, spirituality, peer support, and seeking psychological counseling to manage distress [11,12]. For example, studies in Asia and Africa indicate that religious beliefs and community belongings provide emotional strength and meaning-making frameworks that facilitate adjustment [6,19]. On the contrary, inadequate spousal support, social stigma, or unrealistic expectations of recovery can lead to emotional dissonance and self-alienation [10,13]. Qualitative evidence further illustrates that women often navigate a tension between their inner experience of loss and external pressure to “stay strong” for family or societal expectations [5,15]. Therefore, adaptation is neither linear nor uniformity represents a dynamic psychological negotiation that involves grief, resilience, acceptance, and identity reconstruction.

Breast reconstruction or prosthetic use is often promoted to restore body image and self-confidence. However, the psychosocial benefits of reconstruction remain mixed. The coping review and cross-sectional study indicate that while reconstruction can enhance perceived body integrity and reduce distress for some women, others continue to experience dissatisfaction and identity conflict [20,21]. A multi-county study by Tsantakis et al. (2024) found that women who underwent immediate reconstruction reported higher satisfaction with appearance, but not necessarily greater psychological well-being compared to those who chose delayed or no reconstruction [16]. The decision itself can be emotionally taxing, with concerns about surgical risks, cost, and social expectations influencing choices [10,13]. This complexity reinforces that reconstruction cannot substitute psychological healing; instead, it should be complemented by supportive interventions that address emotional adaptation and self-concept transformation.

Despite substantial research on the clinical and cosmetic outcomes of mastectomy, limited qualitative attention has been paid to the subjective psychological journey that women undertake in redefining their identities after surgery. Existing literature predominantly quantifies depression or body image scores but rarely captures lived experiences that contextualize these outcomes [12,19]. Understanding how women make meaning of their altered bodies, negotiate societal expectations, and reconstruct self-worth is critical for developing holistic postmastectomy care models. Therefore, this study aimed to explore and understand the psychological and emotional adaptation experiences of women who have undergone mastectomy at Mankweng tertiary hospital in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Interestingly, to our knowledge, this will be one of the few qualitative studies conducted in Limpopo Province that specifically explored the psychological and emotional adaptation of postmastectomy women. Furthermore, the present study aims to contribute to a more humanized, integrative understanding of recovery, one that goes beyond physical survival to encompass emotional resilience and renewed self-definition.

1.1. Objective of the Study

The objective of this study was to explore the experiences of women after mastectomy and how they redefine their sense of self and identity during the post-mastectomy period. There is limited understanding of the lived experiences and coping mechanisms of women after mastectomy within the South African context, particularly in Limpopo Province, where cultural, social, and resource factors can influence recovery and self-perception. Therefore, the following research question guided this study: What are the lived psychological and emotional experiences of women after mastectomy at Mankweng tertiary hospital in Limpopo Province?

1.2. Theoretical Framework

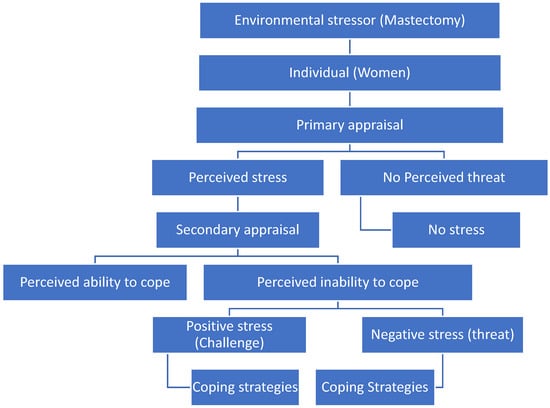

The authors adopted a theoretical framework for stress and coping by Lazarus & Folkman (1984) [22]. This theory explains the dynamic process through which individuals perceive and respond to stressful life events [22]. The theory emphasizes that stress is not only a direct response to external situations but is a result of an individual’s cognitive assessment of a situation and their perceived ability to cope with it [22]. This evaluation involves two main stages: primary evaluation, where a person evaluates whether an event is threatening, harmful, or challenging; and secondary evaluation, where they evaluate their coping resources and options for managing the stressor. Coping strategies are then used, which may be problem-focused, aiming to address or change the source of stress, or emotion-focused, which seeks to regulate emotional responses to the situation. The outcome of this process determines the psychological adaptation and general well-being of the individual. This theory provides a useful framework for understanding how women psychologically and emotionally adjust after mastectomy, as it highlights the role of personal meaning making, available resources, and coping mechanisms in shaping recovery and self-redefinition. The authors further depicted this theory in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Lazarus and Folkman’s theoretical framework of stress and coping (1984) [22]. Source: adapted from Sumbane GO (2024) [23].

In this study, the authors applied the theory to understand how women psychologically and emotionally adapt after mastectomy. It provided a conceptual lens to interpret how participants evaluated their postmastectomy experiences, whether as loss, threat, or opportunity for growth, and the coping mechanisms they used to reconstruct their self-identity.

2. Results

An important theme and three subthemes emerged from this study as illustrated in Table 1. Participants seemed to appreciate having someone who was curious about their postmastectomy experiences during the interview. They expressed their emotions openly. However, they appeared fairly concerned when discussing emotions and concerns.

Table 1.

Themes and sub-themes.

2.1. Theme 1: Feelings After Mastectomy

Participants in this study had negative as well as positive feelings after mastectomy. Some reported feeling disabled, anxious, worried, while others felt relieved after mastectomy.

2.1.1. Feeling of Being Disabled

Participants reported being concerned when they saw the scar in the mirror, this made them feel like their image had changed. The scar in the mirror made the participants feel like their image had changed, which made them concerned. Women see their transformation in appearance as a threat and a challenge since the loss of one or both of their breasts. The study found that women experience stress due to judging their scars, missing body parts, the sensation of feeling different from others and the feeling of being disabled. This was corroborated by four participants who echoed the following:

“I felt incapacitated”.(P5, a 62-year-old woman, married with two children)

“Eish, I was depressed and felt like I wasn’t the same person I was before when I was bathing and going to the mirror”.(P12, 50-year-old woman, married with three children)

“I realized the situation of living with incomplete parts, which made it difficult”.(P4, a 40-year-old widow)

“Observing someone with a single organ while knowing that they are born with two organs is, of course, painful”.(P7, a 34-year-old, single and unemployed woman)

The study also found that in addition to the fear of feeling disabled, the participants felt the scar or themselves hidden from others, including their own family. Losing one or both of their breasts was a reality that women found difficult to accept. Because some of them stopped attending clinics or gatherings, while others stopped permitting anyone in the bathroom when they are bathing or naked. In addition to hiding the scar or themselves, other women also keep their condition secret, even from their own children. These emotions could have an impact on how they cope and control their condition.

As evidenced by:

“I thought I could always hide so that nobody would see me”.(P12, 50-year-old woman, married with three children)

“I don’t want my kids to see what happened, so I no longer let them use the restroom”.(P7, a 34-year-old, single and unemployed woman)

“Obviously everyone will know that I removed my breast; I didn’t go to the clinic”.(P5, a 62-year-old woman, married with two children)

“Once more, some of my kids are unaware that I have cancer”.(P3, a 48-year-old woman from Vhembe district)

2.1.2. Reflection About the Illness

Some of the woman in this study were anxious and uncertain about living with incomplete parts. Other women were concerned and uncertain about the possibility of the cancer returning and spreading after mastectomy. Other circumstances that contributed to their worry and uncertainty were the sense that a mastectomy may have an impact on their fertility and that breastfeeding with only one breast may not be possible.

As evidenced by:

“I mean, what kind of person will I be if this thing comes back and spreads to the other breast?” “All I want is for this to disappear permanently”.(P7, a 34-year-old, single and unemployed woman)

“It might spread to the bones if it was not removed”.(P2, 53-year-old woman, widow with three kids)

“I realized the situation of living with incomplete parts and imagined that I might no longer have children or breastfeed with one breast, so it was difficult”.(P6, 44-year-old women, from Sekhukhune district)

2.1.3. Feeling Positive and Relief

The study also found that other women had positive feelings after mastectomy. They were relieved to see that the weight of the illness they were experiencing was surgically removed. Their favorable attitude was related to the fact that their breast cancer was discovered early and that the breast/s were surgically removed on time. Furthermore, women with smaller breasts claimed to feel the same as before mastectomy and did not believe their appearance had changed. These women saw cancer and mastectomy as a reality that they could face, resulting in positive stress. As evidenced by:

“I didn’t feel stressed because I thought the breast carried a serious illness and there was no other option; perhaps if it were removed, I would feel better and live a long life.”.(P1, 49-year-old woman single and unemployed)

“I was fortunate that my breast cancer did not progress to that stage, therefore I had no trouble living with just one breast. I had heard that many women with breast cancer arrived after their disease was too advanced”.(P14, 54-year-old woman, married with one child)

“Even though I use small bras and do not have enormous breasts, I still feel like I have too many”.(P13, 60-year-old woman, married with 3 children)

2.1.4. Feeling of Acceptance

Most of the women who had a mastectomy at Mankweng Hospital, according to the study, claimed to have accepted it. Some of the participants in this study came to terms with their condition of living with breast cancer and undergoing a mastectomy. Acceptance did not emerge immediately but appeared as a gradual outcome after periods of distress and uncertainty. Their acceptance was contingent upon the reality that mastectomy was the most effective treatment since their breasts were no longer functioning and their lives were at risk. The realization that many people live with cancer gave them hope. For some, mastectomy was the only way to recover. The women acknowledging their current reality to better cope and adapt situation.

It is evidenced by the following quotations:

“Man did not have to give up on breast cancer; it does not help to keep it if it no longer serves any purpose and endangers my life”.(P8, a 47-year-old, unemployed woman)

“I did realize that I am not alone and that I had to accept it as a disease”.(P6, 44-year-old women, from Sekhukhune district)

“I knew that cancer kills and that removing my breast was the only way to be saved, so from the beginning, my spirit was free”.(P4, 40-year-old woman from Waterberg district)

“I want to get better.” “I wanted to heal, so I thought I was okay. I wanted to heal; therefore, I accepted everything”.(P5, a 62-year-old woman, married with 2 children)

“I’ve come to terms with the condition and have begun to celebrate its existence”.(P11, a 36-year-old woman, unemployed, unmarried, a mother of two)

2.2. Theme 2: Challenges Experienced

The study revealed that women who had undergone mastectomy, experienced variety of challenges. The challenges include the symptoms experienced after the operation, during chemotherapy treatment, limited finance for frequent follow-up at the hospital.

2.2.1. Physically Challenges

Like other surgical operations, women who had mastectomy reported experiencing pain and swelling on the operated side, making it challenging to lift or rotate their arms. Some highlighted experiencing some complications postoperatively. Certain women pointed out that the side effects of chemotherapy cause them to feel ill, experience dizziness, suffer from nausea, and even vomit. The physical challenges had an impact on the execution of everyday tasks. As shown by:

“On Saturday morning, I experienced intense pain that felt life-threatening. When I got to the hospital, I was extremely swollen on the surgical side, which I believe worsened the pain. The doctor then drained the fluid and provided me with pain relief, after which I felt better, but I couldn’t use my arm”.(P2, 53-year-old woman, widow with 3 kids)

“When I went back to take out the clips, the side where I had surgery just opened, and they had to stitch me up again, which caused me more pain. Even now, I am quite hesitant to use it since it causes so much pain and prevents me from fulfilling my daily responsibilities”.(P4, 40-year-old widow)

“Chemotherapy is extremely painful; you experience significant dizziness, and recently I vomited for nearly two days without any sleep.” “It usually occurs mainly when I forget the pills designed to stop nausea and vomiting.”(P7, a 34-year-old, single and unemployed woman)

“I experienced pain and felt ill only after receiving chemotherapy injections.” “I spent an entire week with no appetite and vomiting whenever I ate.”(P8, a 47-year-old, unemployed woman)

2.2.2. Financial Challenges

Women who have had a mastectomy often return to the hospital for follow-up, and it is noted that this can lead to significant financial strain, jeopardizing their appointments. The study revealed that women who were self-employed or engaged in temporary jobs were unable to continue due to the physical symptoms or complications they faced, and the frequent hospital visits required. Leading to financial constraints.

The participants noted that each time they went to the hospitals, both local and referral, they had to pay for the files, and some were unemployed; they were solely depending on their parents’ social grants. Other women mentioned that at times they do not have enough money for transportation to their regular hospital visits. It was proposed that it would be preferable for the government to organize transportation to collect them from their homes.

As shown below:

“The hospital is requiring us to pay.” I spend R40 at the local hospital to retrieve the file and conduct blood tests, then R75 at referral hospital”.(P2: 53-year-old women, widow with 3 kids)

“…if they can send transport to collect us, we would benefit from it. Seeing that the transport is costly when going to and from local hospital.”(P11: A 36-year-old woman, unemployed, unmarried, a mother of two)

“They were unable to offer me a light position; therefore, I quit my job due to the pains. I continued to take off for several occasions, and I occasionally let go because I was ill”.(P7: 34-year-old women, from Capricon district)

“We do pay for files; they claim we owe money here, which surprised us since we were not informed from the beginning. I’m not aware of that credit and that amount is quite high, around two thousand”.(P2: 53-year-old women, widow, from Mopani District)

2.2.3. Institutional Resources Challenges

Another challenge faced by participants in public hospitals was the lack of resources to treat them. Some women emphasized that tertiary public hospitals are the only places where resources for managing breast cancer are available. It was noted that one of the tertiary hospitals in the province had a single mammography equipment for the early detection of breast cancer, and if it malfunctioned, the patient’s diagnosis would be delayed, and the breast cancer stages would progress. The participants expressed disappointment and discouragement due to the machine malfunctioning, resulting in prolonged waiting times for the intervention. As quoted below:

“I went to the closest clinic after realizing I had a breast lump, and they wrote me a referral letter to my local hospital. I was disappointed and discouraged when I went to the local hospital and was informed that there were no resources. When I went to the tertiary hospital, I was informed that the mammography machine was damaged. Everywhere I went, I was informed that there was no equipment, which demoralized me once more. Indeed, it was depressing. After that, I returned home and stayed there for a while.”.(P6: 44-year-old women, from Sekhukhune district)

“I was transferred and told that the Mammogram machine is not available is damaged, I was told to go back home and come back at another date. I have been coming back for over six months.”.(P3: 44-year-old woman, widow with one child)

3. Discussion

This study explored the experiences of women after mastectomy at Mankweng Tertiary Hospital in Limpopo Province, South Africa. These include the psychological, emotional adaptation and the challenges experienced. The findings revealed that the women experienced a wide spectrum of emotions ranging from feelings of disability, anxiety, and eventual acceptance of their condition. These results illustrate the multifaceted process of redefining self-identity after mastectomy, highlighting both distress and resilience among affected women.

Participants expressed that physical loss of a breast led to feelings of being ‘disabled’, incomplete, or different from their former self. This perception was intensified by the visible scar, which symbolized a permanent alteration in their body and femininity. These findings are consistent with several studies that have shown that mastectomy often disrupts body image, self-esteem, and perceptions of womanhood [24,25,26]. Similarly, a study conducted in Nigeria found that mastectomy significantly impacted women’s sense of completeness and attractiveness, often leading to social withdrawal and avoidance of intimate situations [27]. The tendency of some participants in this study to hide their scars or avoid family members resonates with findings from a South African qualitative study by Mnisi (2021) [28], which reported that women felt stigmatized and feared judgement from their families and communities.

Although mastectomy is a lifesaving procedure, the psychological burden it imposes can be profound. Many women reported that they avoided public spaces and social gatherings to conceal their condition. Similarly, a study by Owino & Mary (2023) found that women at Kenyatta National Hospital perceived mastectomy as socially isolating, often associating it with shame or diminished femininity [17]. On the contrary, in high-income contexts, where breast reconstruction and psychosocial support services are more readily available, women have reported more positive body image outcomes [29]. This contrast highlights the importance of contextual and cultural factors in shaping post-mastectomy adjustment. In the Limpopo context, were cultural norms link womanhood to physical wholeness, the removal of a breast may be equated with disability or incompleteness, reinforcing the participants’ self-perception of being ‘disabled’.

Anxiety and uncertainty were also prevalent in this study, as many participants expressed fears about recurrence of cancer, spread to other organs, or infertility and inability to breastfeed. These findings mirror those of previous research showing that postmastectomy anxiety is commonly associated with fear of recurrence and decreased control over one’s health [30,31]. Furthermore, the unique concern expressed by participants about their ability to breastfeed or have children underscores the cultural centrality of motherhood in South Africa. Similarly, research in Kenya by Owino & Mary (2023) revealed that women equated their breasts not only with femininity, but also with their ability to nurture and fulfil maternal roles [17]. Although the literature often focuses on body image and sexual functioning, the emphasis on motherhood and breastfeeding in this study highlights a distinct cultural dimension that requires context-sensitive psychological interventions.

However, not all emotional responses were negative. Several women in this study expressed relief and acceptance, perceiving mastectomy as a necessary and life-saving step toward recovery. This transition from despair to acceptance aligns with studies demonstrating that, over time, many women develop coping strategies that facilitate psychological adjustment and meaning making [20,29,32]. Similarly, Zimba’s study (2025) found that acceptance was often associated with spirituality and a strong belief that the removal of the breast symbolized liberation from disease [32]. Similarly, the statements of our participants that they felt ‘healed’ or “relieved” after surgery reflect a process of post-traumatic growth process, where individuals reconstruct a positive identity and regain a sense of control over their lives [33].

The study’s findings fit well with Folkman and Lazarus’ theoretical framework of stress and coping (1984) [22]. According to this research, women who underwent mastectomy viewed their situation as a threat or a challenge. The experience of being disabled, hiding the scar or self-injuring, and feeling uncertainty all contributed to the negative stress and the inability to deal with the problem for those who perceived it as a threat. However, women who perceived mastectomy as a challenge had favorable feelings about procedures that led to positive stress. However, all women in the study said that they had come to terms with their circumstances [20]. However, acceptance did not emerge immediately but appeared as a gradual outcome after periods of distress and uncertainty. This finding supports the adaptive trajectory described in the Folkman and Lazarus theoretical framework of stress and coping [22], which suggests that individuals undergo a progressive transition from physiological and self-concept disruptions to integrated adaptation. Furthermore, the emotional oscillation between fear and acceptance observed in this study indicates that psychological adjustment after mastectomy is dynamic rather than linear, requiring continuous psychosocial support [34,35]. Similarly, evidence from a recent systematic review by Tan et al. (2023) [34] showed that targeted psychosocial interventions, including counseling and peer support, significantly reduced depression and anxiety among breast cancer survivors [36].

The study also emphasized the challenges experienced by women who had mastectomies. Some of the challenges include physical symptoms or issues related to chemotherapy and post-mastectomy treatment. financial difficulties brought on by repeated hospital follow-up appointments and unemployment due to ill health. Another impediment was the public hospital’s lack of resources for the early identification of breast cancer, which resulted in a delay in the diagnosis and caused worry and impact on the prognosis of the condition among the women. According to other research, chemotherapy also has similar adverse effects [34,35]. Delaying the use of mammography screening to identify breast cancer might have a significant impact on the size, stages, treatment, and survival of any later breast cancer [37].

Although the study participants demonstrated remarkable resilience, their narratives highlight the urgent need for structured psychosocial support in post-mastectomy care. Many women in South Africa, especially in public health facilities, receive little to no counseling after surgery, which may hinder their emotional recovery [38]. Integrating mental health services into oncology units could help women manage fear, reconstruct self-identity, and regain social confidence [33]. Furthermore, culturally sensitive educational interventions involving family members could help reduce stigma and promote acceptance at both the individual and community levels. In general, this study affirms that emotional adaptation after mastectomy involves a complex interplay between body image, social identity, and coping mechanisms. While initial reactions of fear and loss dominate the early phase, a gradual shift toward acceptance and redefinition of self occurs as women adapt to their new reality.

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Study Setting

The research took place at the Polokwane/Mankweng hospital complex, which consists of two primary campuses: Mankweng hospital and Pietersburg hospital. Acting as a tertiary facility and educational hospital for the University of Limpopo, delivering various specialist services, and functioning as an essential health provider for the Limpopo province. Mankweng hospital conducts mastectomy surgeries for all women diagnosed with breast cancer in Limpopo Province and offers limited follow-up and review services. Pietersburg hospital provides most follow-ups and evaluations after mastectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation. Data was collected at the Outpatient Department surgical clinics of both hospital campuses.

This created an appropriate environment for identifying women who had experienced mastectomy and were at various stages of their postoperative recovery journey. Additionally, the hospitals offered breast cancer patients counseling and follow-up care, which made it possible to investigate how women adjusted emotionally and mentally to life following mastectomy. The researchers were able to obtain detailed information about women’s experiences with changes in body image, mental distress, and self-redefinition following breast removal by conducting the study in this context.

4.2. Research Design

The authors used a qualitative phenomenological research design to obtain a detailed exploration and understanding of the lived psychological and emotional experiences of women after mastectomy in a tertiary hospital in Limpopo province.

4.3. Sampling of the Participants

A nonprobability purposive sampling method was used to find fifteen female volunteers. During surgical clinic reviews, women who were willing to participate, in stable physical health, and at least twelve weeks post-mastectomy were chosen. After obtaining approval from the hospital’s CEO and the surgical clinic’s operational manager, the researcher began recruiting applicants. The operations manager assigned a nurse to help the researcher find women who were stable and at least 12 weeks post-mastectomy. They were then individually recruited by the researcher, and those who consented took part in the study. Table 2 shows their features. According to Creswell (2014) [39], because the main goal of phenomenological investigations is to gain comprehensive knowledge of the complexity and context surrounding the event being studied, they usually include very small sample sizes [39]. For phenomenological research, a sample size of three to ten people is recommended.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the participants.

4.4. Data Collection

Data was gathered by a male researcher employed in a surgical ward at Polokwane/Mankweng Complex hospital. The researcher possessed over five years of experience working with women diagnosed with breast cancer. The supervisor and the researcher collaborated on the pilot study to guide and prepare the researcher for data collection. Along with careful management of gender dynamics, power conflicts, and biases. Following each interview, the researcher and supervisor would evaluate the gender biases and cultural stereotypes to identify and reduce gender bias in the research process. The women who consented to take part in the pilot study appear to feel at ease discussing their experiences with the researcher.

Data was gathered through semi structured one-on-one interviews that lasted around 45–60 min and were audio recorded with a voice recorder and field notes. The distraction-free space of the outpatient department was used for the interviews. The interviews took place after their consultations. The central question asked was “Please describe your emotional experiences following the mastectomy procedure”. To ensure that all topics were covered, the researcher also used probing questions (interview guide) during the interview. The researcher nodded his head all the time and requested more clarity where there was a lack of understanding. Data was collected up to the saturation point during the 10th interview. However, five additional interviews were conducted to confirm the saturation of the data.

4.5. Data Analysis

The researchers organized, managed, and analyzed qualitative data more easily using NVivo 15 software. In addition to compiling field notes, the researchers transcribed the audio recordings. The data was then subjected to thematic analysis for coding. After getting acquainted with the transcripts, similar patterns were found in the data set, and their underlying meanings were deciphered. After the codes and patterns were identified and categorized, potential themes were generated and conceptualized.

4.6. Ethical Consideration

The Turfloop Research Ethics Committee at the University of Limpopo granted ethical approval for this study (No. TREC/413/2017:PG). The study was approved by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Makweng Hospital, the Operations Manager of the surgical clinic, the Mankweng/Polokwane Complex Research Ethics Committee, and the Limpopo Department of Health Research Ethics Committee. The investigator gathered potential applicants. Before being interviewed, study participants signed an informed permission form attesting to their voluntary involvement.

5. Study Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, it is recommended that holistic psychosocial support be integrated into postmastectomy care to address the emotional, psychological, and social needs of women. Health care providers at Mankweng Tertiary Hospital and similar facilities should incorporate routine counseling, peer support groups, and family education sessions to help women cope with changes in body image, fear of recurrence, and social stigma. Additionally, nurses and oncology staff should receive culturally sensitive communication training to help patients express their feelings and adjust positively after surgery. Collaboration between mental health professionals, social workers, and oncology teams is crucial to ensure comprehensive patient care. At the community level, awareness and education campaigns should be initiated to reduce misconceptions and stigma surrounding mastectomy, thereby promoting acceptance and social reintegration of survivors. Furthermore, given the profound adverse after-effects of mastectomy on the mental, physical, and emotional status of women, it is recommended that communication of these effects be given a higher priority in a risk-benefits analysis before a woman consents to treatment. Future studies should ask women if their medical consent would have been affected had they known the outcome before consenting. Moreover, the issue of anxiety over recurrence in women expressing relief, should be probed deeper in future studies. Finally, further research is recommended to explore long-term adaptation patterns and evaluate the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in improving postmastectomy quality of life among South African women.

6. Study Strengths and Limitations of the Study

A major strength of this study lies in its qualitative design, which provided rich and in-depth insight into the psychological and emotional experiences of women following mastectomy in a South African context. Using the participants’ own narratives, the study captured authentic emotions and coping processes that quantitative methods could have overlooked. Conducting research at Mankweng Tertiary Hospital in Limpopo Province also allowed for the exploration of cultural and social influences that shape women’s adaptation, adding contextual relevance to the existing body of knowledge on postmastectomy recovery in low- and middle-income settings. Furthermore, the use of thematic analysis improved the rigor and credibility of the findings, allowing the identification of common patterns and unique individual perspectives.

The sample was diverse regarding time, as the women involved in this study were post-mastectomy, with durations varying from 12 weeks to 232 weeks, leading to potential differences in their experiences based on the timing. The small sample size and single-site focus limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings or populations. Participants were recruited from two campuses, which may not reflect the experiences of women of different socioeconomic or cultural backgrounds within South Africa. Additionally, self-reported data may have been influenced by recall bias or the desire to present socially acceptable responses, particularly regarding sensitive emotional topics. The absence of longitudinal follow-up also restricted the ability to assess how the emotional adaptation of the participants evolved over time. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable groundwork for future research and offers important implications for improving psychosocial care for women undergoing mastectomy.

7. Conclusions

This study concludes that women’s psychological and emotional adaptation after mastectomy is a complex and deeply personal journey marked by initial distress, fear, and disruption of body image, gradually progressing toward acceptance and resilience. While many participants initially perceived themselves as ‘disabled’ and experienced anxiety about cancer recurrence, infertility, and social stigma, others eventually accepted their condition as a necessary step toward survival and healing. This transformation reflects the remarkable capacity of women to cope and redefine their self-identity despite profound physical and emotional loss. The findings emphasize the importance of holistic, culturally sensitive psychosocial support that extends beyond physical recovery to address emotional healing, body image reconstruction, and social reintegration. Integrating counseling, peer support, and family education into postmastectomy care can promote acceptance, reduce stigma, and improve overall well-being, helping women not only survive breast cancer but reclaim a renewed sense of completeness and purpose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M., G.O.S., T.M.M. and L.W.M.; methodology, D.M., G.O.S. and T.M.M.; validation, G.O.S. and T.M.M.; formal Analysis, G.O.S., T.M.M. and L.W.M.; investigation, D.M.; resources, D.M.; data Curation, D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M., G.O.S., T.M.M. and L.W.M.; writing—review and editing, L.W.M. and G.O.S.; visualization, G.O.S. and L.W.M.; supervision, G.O.S.; project administration, D.M. and L.W.M. All the authors have contributed to the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Turfloop Research Ethics Committee (TREC) (TREC/413/2017:PG) on 2 November 2017.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. As data may contain information that jeopardizes the privacy of research participants, they are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the Limpopo Department of Health and the Mankweng/Pittsburgh Hospital complex for allowing them to do research at their facility. My sincere gratitude goes out to all women in Limpopo province who participated in this study. May the souls of those who passed away after taking part in this research be at peace.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared that they had no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the investigation, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Newman, L.A.; Freedman, R.A.; Smith, R.A.; Star, J.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast cancer statistics 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.K.; Oh, S.; Kim, J.; Choi, J.S.; Hwang, K.T. Psychological impact of type of breast cancer surgery: A national cohort study. World J. Surg. 2022, 46, 2224–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçan, S.; Gürsoy, A. Body image of women with breast cancer after mastectomy: A qualitative research. J. Breast Health 2016, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phoosuwan, N.; Lundberg, P.C. Life satisfaction, body image and associated factors among women with breast cancer after mastectomy. Psycho-Oncology 2023, 32, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erden, Y.; Celik, H.C.; Karakurt, N. Women’s body image after mastectomy: A photovoice study. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, S.; Chew, K.S.; Balang, R.V.; Wong, S.S.L. Beyond the scars: A qualitative study on the experiences of mastectomy among young women with breast cancer in a country with crisis. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 596. [Google Scholar]

- Padmalatha, S.; Tsai, Y.-T.; Ku, H.-C.; Wu, Y.-L.; Yu, T.; Fang, S.-Y.; Ko, N.-Y. Higher risk of depression after total mastectomy versus breast reconstruction among adult women with breast cancer: A systematic review and metaregression. Clin. Breast Cancer 2021, 21, e526–e538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movahed, F.; Dehbozorgi, M.; Goodarzi, S.; Abianeh, F.E.; Bahri, R.A.; Shafiee, A. Effect of breast cancer surgery on levels of depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nano, M.T.; Gill, P.G.; Kollias, J.; Bochner, M.A.; Malycha, P.; Winefield, H.R. Psychological impact and cosmetic outcome of surgical breast cancer strategies. ANZ J. Surg. 2005, 75, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, I.S.; Jensen, D.M.R.; Grosen, K.; Bennedsgaard, K.T.; Ventzel, L.; Finnerup, N.B. Body image and psychosocial effects in women after treatment of breast cancer: A prospective study. Am. J. Surg. 2024, 237, 115895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verri, V.; Pepe, I.; Abbatantuono, C.; Bottalico, M.; Semeraro, C.; Moschetta, M.; De Caro, M.F.; Taurisano, P.; Antonucci, L.A.; Taurino, A. The influence of body image on psychological symptomatology in breast cancer women undergoing intervention: A pre-post study. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1409538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebri, V.; Durosini, I.; Triberti, S.; Pravettoni, G. The efficacy of psychological intervention on body image in breast cancer patients and survivors: A systematic-review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 611954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waks, A.G.; Winer, E.P. Breast cancer treatment: A review. JAMA 2019, 321, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foppiani, J.; Lee, T.C.; Alvarez, A.H.; Escobar-Domingo, M.J.; Taritsa, I.C.; Lee, D.; Schuster, K.; Wood, S.; Utz, B.; Bai, C. Beyond Surgery: Psychological Well-Being’s Role in Breast Reconstruction Outcomes. J. Surg. Res. 2025, 305, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsantakis, V.; Dimitroulis, D.; Kontzoglou, K.; Nikiteas, N. The effect of time since reconstruction on breast cancer patients’ quality of life, self-esteem, shame, guilt, and pride. Palliat. Support. Care 2024, 22, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsantakis, V.; Dimitroulis, D.A.; Kontzoglou, K.C.; Nikiteas, N.I. Investigating the Difference in Quality of Life Between Immediate and Delayed Breast Cancer Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. Cancer Diagn. Progn. 2024, 4, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owino, M.A. Exploring Experiences of Individuals with Breast Cancer Post-Mastectomy at Kenyatta National Hospital-a Phenomenological Study. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Torrisi, C.; Fu, M.R.; Teti, M.; Armer, J.M. “When I Look in the Mirror, I Want to See a Healthy Body”: The Lived Experience of Young Previvors, Bilateral Risk-Reducing Mastectomy, and Body Image. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2025, 12, 23333936251362638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harerimana, A.; Mchunu, G. The use of standardised tools to measure post-mastectomy quality of life among women in Africa: A scoping review. BMC Women’s Health 2025, 25, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, N.; Downes, M.H.; Ibelli, T.; Amakiri, U.O.; Li, T.; Tebha, S.S.; Balija, T.M.; Schnur, J.B.; Montgomery, G.H.; Henderson, P.W. The psychological impacts of post-mastectomy breast reconstruction: A systematic review. Ann. Breast Surg. 2024, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sançar, B.; Akan, N.; Süren Akpolat, N.; İnanç, Ş. Examination of body image perception and quality of life of women with segmental or total mastectomy: A cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2025, 25, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S. Stress: Appraisal and coping. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1913–1915. [Google Scholar]

- Sumbane, G.O. Coping strategies adopted by caregivers of children with autism in the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Afr. J. Disabil. (Online) 2024, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, B.N.; Van Dorn, R.; Myers, B.J.; Zule, W.A.; Browne, F.A.; Carney, T.; Wechsberg, W.M. Barriers and facilitators to implementing an evidence-based woman-focused intervention in South African health services. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syrowatka, A.; Motulsky, A.; Kurteva, S.; Hanley, J.A.; Dixon, W.G.; Meguerditchian, A.N.; Tamblyn, R. Predictors of distress in female breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 165, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.; Salmon, P.; Tudur-Smith, C.; Huntley, C.D.; Fisher, P.L. A systematic review of the quality of randomized controlled trials of psychological treatments for emotional distress in breast cancer. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 108, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikharo, E.; Gondwe, K.W.; Conklin, J.L.; Zimba, C.C.; Bula, A.; Jumbo, W.; Wella, K.; Mapulanga, P.; Idiagbonya, E.; Bingo, S.A. Psychosocial experiences of cancer survivors and their caregivers in sub-Saharan Africa: A synthesis of qualitative studies. Psycho-Oncology 2023, 32, 760–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioku, A.A.; Jimeta-Tuko, J.D.; Harris, P.; Lu, B.; Kareem, A.; Sarimiye, F.O.; Kolawole, O.F.; Onwuameze, O.E.; Ostermeyer, B.K.; Olagunju, A.T. Psychosocial wellbeing of patients with breast cancer following surgical treatment in Northern Nigeria. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnisi, D. Experiences of Patients Who Had Undergone Mastectomy at Mankweng Hopital in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.-Y.; Shu, B.-C.; Chang, Y.-J. The effect of breast reconstruction surgery on body image among women after mastectomy: A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 137, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Pandey, A.K.; Dimri, K.; Jyani, G.; Goyal, A.; Prinja, S. Health-related quality of life among breast cancer patients in India. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 9983–9990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Lim, J.-W. Cognitive behavioral therapy for reducing fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) among breast cancer survivors: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimba, F. Quality of Life and Coping Strategies for Breast Cancer Patients Who Have Undergone Mastectomy at St Francis Mission Hospital in Katete, Zambia. Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.; Qin, M.; Liao, B.; Wang, L.; Chang, G.; Wei, F.; Cai, S. Effectiveness of peer support on quality of life and anxiety in breast cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Care 2023, 18, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wu, Y.; Cong, W.; Hu, M.; Li, X.; Zhou, C. Experience of women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy: A systematic review of qualitative research. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 1249–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddie, N.; Agnew, S.; Crawford, M.; Dixon, D.; MacPherson, I.; Fleming, L. The impact of medication side effects on adherence and persistence to hormone therapy in breast cancer survivors: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. Breast 2021, 58, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, L.J.; Avery, C.S.; Hendrick, E.; Baker, J.A. Benefits and risks of mammography screening in women ages 40 to 49 years. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2022, 13, 21501327211058322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.