Abstract

To improve shared decision-making about the potential risks and benefits of hormone therapy (HT), it is crucial to understand the joint effects of menopausal age and HT use on hypertension onset. This study examines the combined and individual effects of age at menopause and HT on hypertension onset in U.S. women based on their hysterectomy and oophorectomy history. This population-based, cross-sectional study included 4776 postmenopausal women with and without hysterectomy and oophorectomy history from the 2011–2020 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Age at hypertension onset was defined as the time scale at which a respondent was diagnosed with hypertension following the menopause onset. The weighted prevalence of hypertension was 40.0% (95% CI 38.2–41.8%) overall, highest in those who had an oophorectomy with or without hysterectomy (51.6%), followed by those with hysterectomy alone (45.3%), then in those with an intact uterus and ovaries (33.7%), p < 0.0001. Among women with an intact uterus and ovaries, those who experienced menopause before age 45 and used HT had a comparable risk of hypertension (aHR = 1.34, 95% CI: 0.81–2.22) to women who experienced menopause between ages 45 and 54 and did not use HT. Conversely, women who experienced menopause before age 45 and did not use HT showed a significantly increased risk of hypertension (aHR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.27–2.22). The findings suggest that the absence of ovaries, with or without a uterus, HT use, and age at menopause are associated with the likelihood of hypertension development. This study highlights the need for personalized management and decision-making to reduce the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease in peri- and postmenopausal women.

1. Introduction

Nearly one-half of adults in the United States have hypertension, an often preventable medical condition that is a major modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), the leading cause of death [1]. While the prevalence of hypertension is higher in men (30%) than women (16%) from ages 18–39 years, rates are similar at 40–59 years (56% vs. 49%) and ≥60 years (73% vs. 71%) [2]. The prevalence of hypertension in midlife and beyond for women can be influenced by gynecological surgeries that impact ovarian function and age at menopause. For instance, removing the uterus (hysterectomy alone) might affect the peripheral blood flow to the remaining ovaries, thus impacting their endocrine function, and possibly leading to the earlier onset of ovarian senescence associated with menopause [3]. A bilateral oophorectomy, or removal of both ovaries, confers immediate menopause if performed prior to menopause. However, estradiol, the primary form of estrogen produced by the ovary, is a potentially protective hormone against CVD and hypertension. It declines during perimenopause, then drops off abruptly with menopause [4,5]. Given that both hysterectomy (regardless of concomitant oophorectomy) [6] and menopause [5,7,8] are associated with increased incidence of hypertension, a nuanced understanding of surgical history and age at menopause could enable more precise estimates for personalized care and prevention of CVD.

To optimize accuracy in clinical stratification tools, several modifiable and non-modifiable factors that could mitigate the likelihood of hypertension development should be considered. Hormone Therapy (HT) is often prescribed during perimenopause to manage symptoms associated with this transition and has been both positively and negatively associated with hypertension [9,10]. A recent meta-analysis found that those entering menopause before the age of 45 were more likely to develop hypertension than those ages 45 and older [4]. In one study of NHANES data from 2011 to 2014, there was an inverse association between age at menopause and hypertension, a 1.6% (odds ratio [OR] 0.98, 95% CI 0.97–0.998) reduction in the odds of hypertension for each 1-year increase in age at menopause [11]. However, a study from China reported a positive association between age at menopause and hypertension (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.03), and a 2% increase in the odds of hypertension for each 1-year increase in age at menopause [12]. This comparison suggests additional factors may be at play than age alone. While early menarche was not associated with postmenopausal hypertension incidence [11,13], a shorter reproductive lifespan was associated with greater odds of hypertension [14,15]. Taken together, the combined effects of age at menopause and HT use on hypertension are not yet clear.

To date, studies leveraging NHANES data have analyzed hypertension as a dichotomous variable rather than focusing on the age of hypertension onset. Current CVD risk calculators do not incorporate gynecological surgery history, age of menopause onset, or HT use, although these variables may be important to include [11]. Furthermore, evaluating age at hypertension onset may provide more precise estimates and subsequently allow for more targeted treatment recommendations. This study aimed to investigate the combined and individual effects of age at menopause and use of HT on hypertension onset among postmenopausal women in the United States, while accounting for gynecological surgery history. Utilizing data from NHANES, we hypothesized that earlier age at menopause is associated with an increased risk of hypertension onset, and HT use may modify this relationship.

2. Results

2.1. Sample Characteristics

The prevalence of hypertension was summarized by sample characteristics and medical history (Table 1) and stratified by uterine and ovarian surgical history. The prevalence of hypertension was highest in those who had oophorectomy with or without hysterectomy (51.6%), followed by those with hysterectomy alone (45.3%), then in those with intact uterus and ovaries (33.7%), p < 0.001. A significantly greater weighted prevalence of hypertension was observed in women who were smokers compared to non-smokers. This association was particularly evident in women with intact uterus and ovaries (38.3% smokers vs. 30.3% non-smokers, p = 0.001) but not in those who had undergone hysterectomy alone or oophorectomy.

Table 1.

Weighted prevalence of hypertension by the sample characteristics and medical history (N = 4776).

The weighted mean values and SEs, categorized by uterine and ovarian surgical history, are presented in Table 2. The mean age at hypertension onset was significantly lower in respondents who underwent hysterectomy alone (54.7 years, SE = 0.65) and oophorectomy with or without hysterectomy (54.4 years, SE = 0.55) compared to those with intact uterus and ovaries (57.9 years, SE = 0.42), p < 0.001.

Table 2.

Weighted means by the sample characteristics and medical history (N = 4776).

2.2. Unadjusted Analyses

Without adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics (Table 3), women who experienced menopause before age 45 and did not use HT (<45 years + No HT) had a higher rate of hypertension onset compared to those who experienced menopause between ages 45 and 54 and did not use HT, regardless of hysterectomy and oophorectomy history. Women who experienced menopause before age 45 and used HT (<45 years + HT) and reported intact uterus and ovaries or hysterectomy alone had a higher rate of hypertension onset compared to those who experienced menopause between ages 45 and 54 and did not use HT.

Table 3.

Unadjusted hazard ratio of hypertension onset: NHANES 2011 to 2020 (N = 4776).

2.3. Adjusted Analyses

Table 4 shows the aHR of early onset hypertension by hysterectomy and/or oophorectomy history. Across all three surgical history categories, Black respondents and respondents meeting obesity criteria had a higher aHR, whereas higher age at menopause was associated with lower aHR. Among respondents with an intact uterus and ovaries, aHRs were higher for Asian respondents, respondents with a high school education or less, and those reporting lifetime smoking. Among respondents with a hysterectomy alone, respondents with another (Other) race and ethnicity, and a household income below the poverty level had a higher aHR. Asian respondents with an oophorectomy history also had a higher aHR. Among respondents with earlier menopause onset (<45 years), no association was found between HT use and the age of hypertension onset, regardless of hysterectomy and oophorectomy surgical history.

Table 4.

Adjusted hazard ratio of hypertension onset: NHANES 2011 to 2020 (N = 4776).

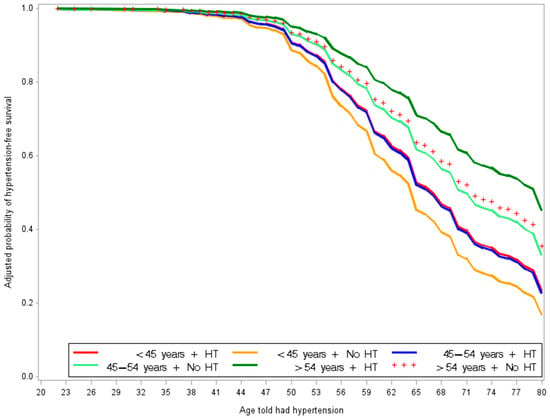

Among respondents with an intact uterus and ovaries, the likelihood of developing hypertension was similar between women who experienced menopause before age 45 and used HT (aHR = 1.34, 95% CI: 0.81–2.22) compared to those who experienced menopause between ages 45 and 54 and did not use HT. Compared to those who experienced menopause between ages 45–54 years and did not use HT, aHR of hypertension were higher for those who experienced menopause before age 45 and did not use HT (uterus and ovaries intact, aHR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.27–2.22; hysterectomy alone, aHR = 2.48, 95% CI: 1.81–3.40; oophorectomy with or without hysterectomy, aHR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.18–2.57). Among respondents with menopause onset between 45 and 54 years, aHR was higher for those with intact uterus and ovaries who reported HT use (aHR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.06–1.78) compared to those who did not. There was no significant association between HT use and age of hypertension onset in this menopause onset group among those with past surgical histories. Among respondents with menopause onset 55 and older, the only significant association was seen among those with a hysterectomy alone who reported HT use (aHR = 1.89, 95% CI: 1.06–3.35) compared to menopause onset ages 45–54 years without reported HT use (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adjusted probability of hypertensive onset-free by the combined effects of age at menopause and HT use in women who reported uterus and ovaries intact. This figure shows that non-HT users who experienced menopause before age 45 (orange) had the highest likelihood of earlier hypertension onset. In contrast, women who experienced menopause after age 54 and used HT (dark green) had the lowest likelihood of earlier hypertension onset.

Sensitivity analyses (Table 5) were consistent with the primary study findings in which the reference group had menopause onset between ages 45–54 years without HT use. Among respondents who experienced natural menopause, the likelihood of developing hypertension was similar between women who experienced menopause before age 45 and used HT (aHR = 1.47, 95% CI: 0.85–2.52) but significantly higher for women who experienced menopause before age 45 and did not use HT (aHR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.06–1.82). Whereas for those who experienced surgical menopause, menopause before age 45 was associated with a higher likelihood of hypertension development with (aHR = 2.76, 95% CI: 1.95–3.91) and without (aHR = 2.45, 95% CI: 1.70–3.54) reported HT use, as was menopause ages 45–54 years with reported HT use (aHR = 1.66, 95% CI: 1.13–2.43).

Table 5.

Adjusted hazard ratio of hypertension onset: NHANES 2013 to 2020 (N = 3516).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Population

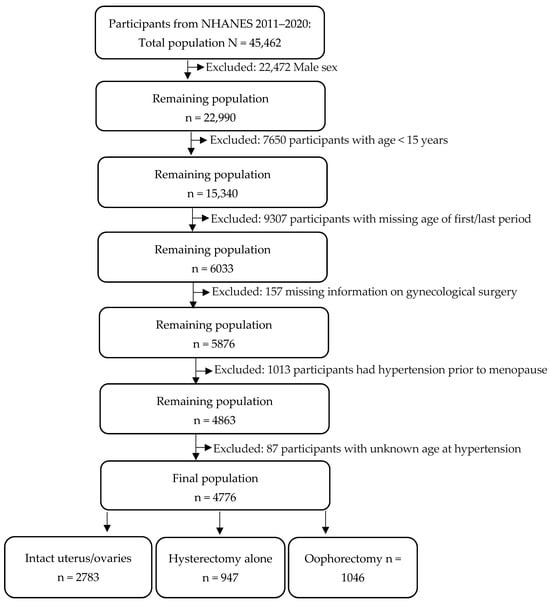

This study employed secondary data from NHANES, a national cross-sectional survey of the civilian, non-institutionalized U.S. population [16]. NHANES received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The deidentified data files for this study are publicly available online here: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx (accessed on 20 June 2024). The survey employed a multistage probabilistic methodology to collect demographic and examination data to obtain nationally representative estimates. We combined data from five survey cycles spanning 2011 through 2020: 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016, and 2017–2020 (N = 45,462). The study population included postmenopausal women as determined by their self-reported gender and ag e of last period. The process for selecting study participants is illustrated in the flowchart in Figure 2. The final analytic sample contained 4776 postmenopausal women. Of the analytic sample, 58% (n = 2783) reported having an intact uterus and ovaries (history of no surgery), 20% (n = 947) underwent hysterectomy alone (RHD280, removal of the uterus), and 22% (n = 1046) underwent oophorectomy (RHQ305, removal of both ovaries) with or without hysterectomy.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of participant selection.

For sensitivity analyses, we categorized respondents into two groups: natural menopause and surgical menopause, based on their answers to question #RHD043, “What is the reason that you have not had a period in the past 12 months?” The response options included menopause/change of life (categorized as natural menopause), hysterectomy (categorized as surgical menopause), pregnancy, breastfeeding, other, missing, refused, or don’t know. Among the 35,706 respondents who participated in survey cycles from 2013 to 2020, 3516 respondents remained after excluding pregnancy, breastfeeding, or other, missing, declined to report, or did not know why they had not had a period in the past 12 months.

3.2. Assessment of Hypertension-Onset Age

The primary outcome was the time to hypertension onset. Respondents were asked “BPQ020: Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had hypertension, also called high blood pressure?” with dichotomous yes/no response options. The response options “refused” and “don’t know” were excluded. Age at hypertension onset was self-reported, BPD035. We defined age at hypertension onset as the time scale at which a respondent was diagnosed with hypertension following the onset of menopause. Respondents were asked, “How old were you when you were first told that you had hypertension or high blood pressure?” For respondents who reported not having hypertension, the age at participation was used and treated as censored data.

3.3. Assessment of Menstrual and Reproductive Factors

Menopausal status was determined based on the self-reported age of the last menstrual period. Age at menopause was analyzed as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable (<45 years, 45 to 54 years, and >54 years) [17]. We evaluated self-reported information on age at the first menstrual period. We computed the duration of reproductive lifespan in years by subtracting age at menarche from age at menopause. Lastly, HT use was assessed by asking, “Have you ever used female hormones such as estrogen and progesterone? Please include any forms of female hormones, such as pills, cream, patch, and injectables, but do not include birth control methods or use for infertility.” To evaluate the combined effect of age at menopause and HT on hypertension onset we created six categories: (<45 years + HT); (<45 years + No HT); (45–54 years + HT); (45–54 years + No HT); (>54 years + HT); and (54 years + No HT) [18].

3.4. Respondent Characteristics

Demographic variables included race and ethnicity (Asian, Black, Hispanic, Other, White), marital status (married/partnered, never married, other), institutional education level (high school or less, college or above), household income below 100% of the federal poverty line (poverty income ratio (PIR) < 1: yes or no), obesity (body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher: yes or no), and smoking status defined as smoking at least 100 cigarettes over a lifetime (yes or no).

3.5. Data Analysis

Estimates were generated using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All analyses were weighted based on the combined surveys (9.2 years, 2011–March 2020) [19]. The weighted mean ± standard error (SE) and percentage (%) were used to describe continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The SE of the population estimates was determined using the Taylor series linearization method. The Rao–Scott Chi-square χ2 test was used to compare the weighted prevalence of hypertension (Table 1). Weighted linear regression was used to produce an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare means (Table 2). We used weighted Cox proportional hazards (CPH) models to evaluate the associations between individual and combined effects of age at menopause and HT use on hypertension onset. Crude (Table 3) and adjusted (Table 4) hazard ratios (HR and aHR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to assess the strength of associations. The model adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics: race and ethnicity, marital status, education level, below-poverty-level, obesity, and smoking status. To avoid collinearity, each reproductive factor was evaluated separately, accounting for sociodemographic characteristics. For sensitivity analyses (Table 5), we analyzed two groups: natural menopause and surgical menopause, to assess the robustness of our findings. A p-value (p) of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

The focus of this study was to investigate the combined effects of age at menopause and HT use on hypertension onset in women. Among respondents with an intact uterus and ovaries, the likelihood of developing hypertension was significantly higher for women who experienced menopause before age 45 and did not use HT, and similar for women who used it, compared to those who experienced menopause between ages 45 and 54 and did not use HT. These findings remained consistent in the sensitivity analysis of respondents who experienced natural menopause before age 45. Among those with prior surgeries, respondents with earlier menopause onset (<45 years) with and without reported HT use had a higher likelihood of postmenopausal hypertension, relative to those with later menopause onset (45–54 years) who did not use HT.

These findings provide a nuanced understanding of previous research, including studies correlating hysterectomy, oophorectomy, and earlier menopause onset with hypertension incidence [2,3,4,6,11,20,21,22]. However, the present findings are different from prior research, which found that menopause onset before age 40 with HT use was associated with a higher incidence of stroke in those without prior hysterectomy or oophorectomy [18]. The inconsistency between this and prior studies might be due to differences in outcomes (hypertension versus stroke), age stratification (e.g., ages < 45 years versus < 40 years; reference groups’ ages 45–54 years versus 50–51 years), and covariates. Our study suggests that age at menopause combined with HT use can offer more precise estimates to improve risk stratification of cardiovascular risk factors. Taken together, longitudinal studies that account for variation in HT and surgical history within the context of menopause onset are needed to clarify the temporality of these findings.

In this study, an estimated 40% of respondents had postmenopausal hypertension, which was higher among those who received oophorectomy (52%) or hysterectomy (45%) compared to those who did not (34%). This finding is consistent with previous studies that reported these gynecological surgeries were correlated with subsequent hypertension [20,21]. However, a limitation of this study is a lack of information regarding surgical timing and reasons for surgery, both of which have been demonstrated to potentially impact CVD incidence. The findings further highlight the need for considering surgical history to establish preventive strategies.

HT use in the present study was limited to a single question assessing lifetime use, preventing definitive estimation of hypertension development. Per previous research, HT duration [23], administration route [24], and composition/formulation [10] may have unique relationships with hypertension development. In women who had experienced menopause and did not have a hysterectomy, postmenopausal HT use was associated with greater odds of hypertension, particularly in younger postmenopausal women, and odds increased with HT duration [23]. Another recent study found oral estrogen-only postmenopausal HT use was associated with an increased risk of hypertension [24].

Black (40%) and Asian (37%) respondents experienced disproportionately higher hypertension prevalence, relative to White respondents (34%). In adjusted models, Asian and Black respondents were more likely to develop postmenopausal hypertension. It is unclear the extent to which the present findings could be accounted for by structural factors, such as delays in diagnosis [25], access to care [26,27,28], and environmental exposures [29,30,31,32,33,34]. Previous research indicated longer delays of formal hypertension diagnoses for female patients, those ages 45–64, and Asian and Black patients, which in turn, were associated with a lower likelihood of antihypertensive medication prescription [23]. Another study found disproportionate rates of undiagnosed hypertension in Black, relative to White participants, which further widened when accounting for neighborhood deprivation [29]. In a 10-year longitudinal study of women ages 42–52 years at baseline, neighborhood socioeconomic conditions were associated with annual average increases in systolic blood pressure among study participants [30]. Both neighborhood socioeconomic conditions and adverse experiences (e.g., discrimination, sexual assault, workplace sexual harassment) were not included in the present study, but are consistently correlated with hypertension incidence, especially among women [31,32,33,34,35]. Similarly, neighborhood deprivation has also been associated with lower HT prescribing rates and, when prescribed, a higher likelihood of oral HT receipt [36]. Taken together, future research that incorporates aspects of lived experiences could be used to tailor screening and prevention programs that address both perimenopausal hypertension and HT.

Limitations

Our findings have several limitations. NHANES data rely on self-reported information regarding age at menopause, age at menarche, and age at hypertension diagnosis, which may introduce recall and misclassification bias. The cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality between age at menopause and hypertension, though subjects reporting having hypertension prior to the age of their last period were excluded. Despite adjusting for multiple variables, residual confounding may remain. For example, factors related to overall health and access to healthcare are not always comprehensively captured in NHANES. We analyzed a question (RHQ305) about whether both ovaries were removed, as this results in immediate menopause at the time of surgery. It is necessary to evaluate CVD risk in women who have had one ovary removed or both ovaries removed at different times. We did not consider timing and indication of surgery due to the lack of these data in certain years. We also did not consider the time of initiation of HT or onset of use, duration, dosage, and route of administration (oral versus transdermal, etc.). The NHANES dataset lacks data regarding the reasons for uterus and ovary removal.

Despite its limitations, this study provides insights into hypertension onset in postmenopausal women. Our study used a large, nationally representative sample of postmenopausal women in the United States, enhancing its generalizability and reproducibility to the source population. Additionally, the Cox proportional hazards model with a time scale of chronological age was appropriate for analyzing time to hypertension onset following menopause and accounting for censoring. The significance of this study lies in the potential to influence clinical practice by suggesting that a woman’s age at menopause and use of HT should be considered when assessing her lifetime risk for CVD and hypertension, especially for the high-risk group of women who experience menopause before age 45. Findings from NHANES 2011–2020, which were observational rather than experimental, suggested that the model’s performance warrants further investigation through randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to establish evidence for the study hypothesis.

Estrogen is thought to exert an anti-inflammatory effect on the cardiovascular system. Hypertension diagnoses increase at the time of menopause and years thereafter, where a decrease in the levels of circulating estradiol is thought to contribute to a rise of 4–5 mm Hg in the average systolic blood pressure. Supplementing with HT is associated with reduced low-density lipoprotein values, as well as decreased abdominal adiposity, and a lower risk of developing Type II DM, all of which are cardiovascular risk factors [7,37]. Longitudinal studies will be instrumental in elucidating the significance of the impact of HT on the influence on cardiometabolic risk factors in peri- and postmenopausal women.

5. Conclusions

The findings suggest that uterine and ovarian status and HT may be associated with postmenopausal hypertension. This study underscores the critical need for personalized management and decision-making strategies for peri- and postmenopausal women, aiming to reduce their individual risk of developing hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and associated morbidity and mortality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; Writing—original draft, R.-P.C., L.B., K.B.H., E.S. and A.E.A.; Supervision, A.E.A., L.B., K.B.H., C.T.W. and J.D.M.; Formal analysis, R.-P.C., B.D. and A.E.A.; Writing—review and editing, all authors. R.-P.C. and L.B. contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data from the NHANES are publicly accessible online via the following link: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx (accessed on 20 June 2024).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the study participants for their contributions to making this study possible. The authors thank the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) for providing public access to data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., the Department of War (DoW), the Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- Xu, J.; Murphy, S.L.; Kochanek, K.D.; Arias, E. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2022; pp. 1–8. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db456.htm (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Fryar, C.D.; Kit, B.; Carroll, M.D.; Afful, J. Hypertension Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control among Adults Ages 18 and Older: United States, August 2021–August 2023. NCHS Data Brief. 2024; p. CS354233. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK612761/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Trabuco, E.C.; Moorman, P.G.; Algeciras-Schimnich, A.; Weaver, A.L.; Cliby, W.A. Association of ovary-sparing hysterectomy with ovarian reserve. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 127, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagnostis, P.; Theocharis, P.; Lallas, K.; Konstantis, G.; Mastrogiannis, K.; Bosdou, J.K.; Lambrinoudaki, I.; Stevenson, J.C.; Goulis, D.G. Early menopause is associated with increased risk of arterial hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2020, 135, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coylewright, M.; Reckelhoff, J.F.; Ouyang, P. Menopause and hypertension: An age-old debate. Hypertension 2008, 51, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madika, A.L.; MacDonald, C.J.; Gelot, A.; Hitier, S.; Mounier-Vehier, C.; Beraud, G.; Kvaskoff, M.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Bonnet, F. Hysterectomy, non-malignant gynecological diseases, and the risk of incident hypertension: The E3N prospective cohort. Maturitas 2021, 150, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, B.; Srivaratharajah, K.; Davis, L.L.; Parapid, B. Women and Hypertension: Beyond the 2017 Guideline for Prevention, Detection. Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. An Expert Analysis. 27 July 2018. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/850339323/Women-and-Hypertension-Beyond-the-2017-Guideline-for-Prevention-Detection-Evaluation-And-Management-of-High-Blood-Pressure-in-Adults (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Yu, J.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Xu, X.; Li, M. Association between serum Klotho concentration and hypertension in postmenopausal women, a cross-sectional study from NHANES 2013–2016. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swica, Y.; Warren, M.P.; Manson, J.E.; Aragaki, A.K.; Bassuk, S.S.; Shimbo, D.; Kaunitz, A.; Rossouw, J.; Stefanick, M.L.; Womack, C.R. Effects of oral conjugated equine estrogens with or without medroxyprogesterone acetate on incident hypertension in the Women’s Health Initiative hormone therapy trials. Menopause 2018, 25, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Campos, L.; Gabrielli, L.; Almeida, M.D.; Aquino, E.M.; Matos, S.M.; Griep, R.H.; Aras, R. Hormone therapy and hypertension in postmenopausal women: Results from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2022, 118, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wen, X.; Zhou, L. Reproductive health factors in relation to risk of hypertension in postmenopausal women: Results from NHANES 2011–2014. Medicine 2023, 102, e35218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Liu, T.; Guo, J.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, R.; Miles, T.; Li, C. Associations of the ages at menarche and menopause with blood pressure and hypertension among middle-aged and older Chinese women: A cross-sectional analysis of the baseline data of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Hypertens. Res. 2019, 42, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, L.C.; Zaniqueli, D.; Andreazzi, A.E.; de Oliveira, C.M.; Pereira, A.C.; de Oliveira Alvim, R. Association between early menarche and hypertension in pre and postmenopausal women: Baependi Heart Study. J. Hypertens. 2025, 43, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.R.; Waller, M.; Chung, H.F.; Mishra, G.D. Association between reproductive lifespan and risk of incident type 2 diabetes and hypertension in postmenopausal women: Findings from a 20-year prospective study. Maturitas 2022, 159, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, C.; Cao, X.; Song, Y.; Zhou, H.; Tian, Y.; et al. Reproductive lifespan in association with risk of hypertension among Chinese postmenopausal women: Results from a large representative nationwide population. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 898608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Shadyab, A.H.; Macera, C.A.; Shaffer, R.A.; Jain, S.; Gallo, L.C.; Gass, M.L.; Waring, M.E.; Stefanick, M.L.; LaCroix, A.Z. Ages at menarche and menopause and reproductive lifespan as predictors of exceptional longevity in women: The Women’s Health Initiative. Menopause 2017, 24, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Chung, H.F.; Dobson, A.J.; Pandeya, N.; Giles, G.G.; Bruinsma, F.; Brunner, E.J.; Kuh, D.; Hardy, R.; Avis, N.E.; et al. Age at natural menopause and risk of incident cardiovascular disease: A pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e553–e564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbami, L.J.; Chen, T.C.; Davy, O.; Ogden, C.L.; Fink, S.; Clark, J.; Riddles, M.K.; Mohadjer, L.K. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2017-March 2020 Prepandemic File: Sample Design, Estimation, and Analytic Guidelines; Vital and Health Statistics, Ser. 1, Programs and Collection Procedures; U.S. Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; pp. 1–36.

- Chhabra, P.; Behera, S.; Sharma, R.; Malhotra, R.K.; Mehta, K.; Upadhyay, K.; Goel, S. Gender-specific factors associated with hypertension among women of childbearing age: Findings from a nationwide survey in India. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 999567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, A. Association between hysterectomy and hypertension among Indian middle-aged and older women: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070830corr1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Shen, L.; Li, H.; Liu, B.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, L.; Liang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y. Age at natural menopause and hypertension among middle-aged and older Chinese women. J. Hypertens. 2018, 36, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.L.; Lujic, S.; Thornton, C.; O’Loughlin, A.; Makris, A.; Hennessy, A.; Lind, J.M. Menopausal hormone therapy is associated with having high blood pressure in postmenopausal women: Observational cohort study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kalenga, C.; Metcalfe, A.; Robert, M.; Nerenberg, K.; MacRae, J.; Ahmed, S. Association Between the Route of Administration and Formulation of Estrogen Therapy and Hypertension Risk in Postmenopausal Women: A Prospective Population-Based Study. Hypertension 2023, 80, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Brush, J.E.; Kim, C.; Liu, Y.; Xin, X.; Huang, C.; Sawano, M.; Young, P.; McPadden, J.; Anderson, M.; et al. Delayed Hypertension Diagnosis and Its Association With Cardiovascular Treatment and Outcomes. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2520498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Turkson-Ocran, R.A.; Foti, K.; Cooper, L.A.; Himmelfarb, C.D. Associations between social determinants and hypertension, stage 2 hypertension, and controlled blood pressure among men and women in the United States. Am. J. Hypertens. 2021, 34, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyelure, O.P.; Jaeger, B.C.; Oparil, S.; Carson, A.P.; Safford, M.M.; Howard, G.; Muntner, P.; Hardy, S.T. Social determinants of health and uncontrolled blood pressure in a national cohort of black and white US adults: The REGARDS study. Hypertension 2023, 80, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedagarla, C.; Pradeep, A.; Pradeep, R. Prevalence of Cardiometabolic Disease in Iowa: A County-Level Analysis of Ethnic Disparities and Screening Gaps. Cureus 2025, 17, e85224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivier, C.A.; Renedo, D.B.; Sunmonu, N.A.; de Havenon, A.; Sheth, K.N.; Falcone, G.J. Neighborhood deprivation, race, ethnicity, and undiagnosed hypertension: Results from the All of Us Research Program. Hypertension 2024, 81, e10–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiff, M.D.; Mair, C.F.; Barinas-Mitchell, E.; Brooks, M.M.; Méndez, D.D.; Naimi, A.I.; Reeves, A.; Hedderson, M.; Janssen, I.; Fabio, A. Longitudinal profiles of neighborhood socioeconomic vulnerability influence blood pressure changes across the female midlife period. Health Place 2023, 82, 103033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, J.A.; Kawachi, I.; White, K.; Bassett, M.T.; Williams, D.R. Instrumental variable analysis of racial discrimination and blood pressure in a sample of young adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 192, 1971–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, R.B.; Nishimi, K.M.; Sumner, J.A.; Chibnik, L.B.; Roberts, A.L.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Koenen, K.C.; Thurston, R.C. Sexual violence and risk of hypertension in women in the Nurses’ Health Study II: A 7-Year prospective analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e023015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffey, A.E.; Rosman, L.; Sico, J.J.; Haskell, S.G.; Brandt, C.A.; Bathulapalli, H.; Han, L.; Dziura, J.; Skanderson, M.; Burg, M.M. Military sexual trauma and incident hypertension: A 16-year cohort study of young and middle-aged men and women. J. Hypertens. 2022, 40, 2307–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blazel, M.M.; Perzynski, A.T.; Gunsalus, P.R.; Mourany, L.; Gunzler, D.D.; Jones, R.W.; Pfoh, E.R.; Dalton, J.E. Neighborhood-level disparities in hypertension prevalence and treatment among middle-aged adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2429764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.J.; Williams, A.; Azap, R.A.; Zhao, S.; Brock, G.; Kline, D.; Odei, J.B.; Foraker, R.; Sims, M.; Brewer, L.C.; et al. Role of sex in the association of socioeconomic status with cardiovascular health in Black Americans: The Jackson Heart Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e030695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, S.; Shantikumar, S.; Ridha, A.; Todkill, D.; Dale, J. Socioeconomic status and HRT prescribing: A study of practice-level data in England. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 70, e772–e777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, R.; Wofford, M.; Reckelhoff, J.F. Hypertension in postmenopausal women. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2012, 14, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.