Emotional Eating Associated with Poor Body Satisfaction in Women with Obesity: Theory-Based Psychosocial Mediators in Weight Management Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Correlates of Emotional Eating at Baseline

3.2. Changes in Study Measures, by Group

3.3. Effects of Group Processes on Emotional Eating and Its Psychosocial Mediators

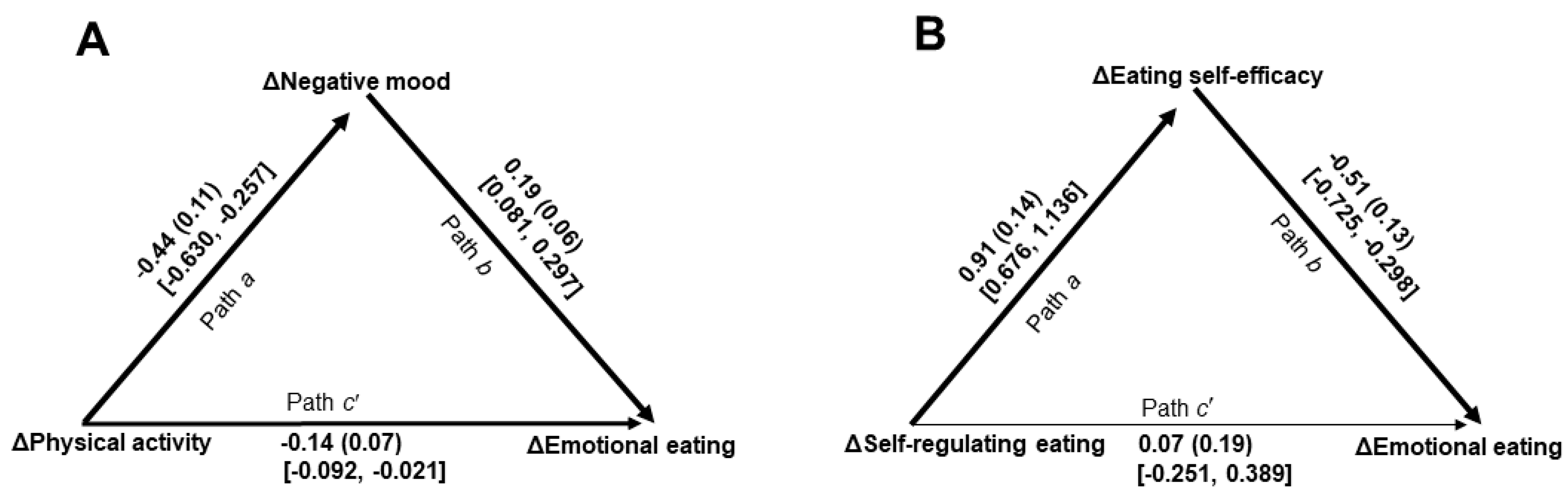

3.4. Effects of Treatment Targets on Emotional Eating Through Identified Mediators

3.5. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EmE | Emotional eating |

| BAS | Body areas satisfaction |

| BMI | Body mass index |

References

- Cannon, C.P.; Kumar, A. Treatment of overweight and obesity: Lifestyle, pharmacologic, and surgical options. Clin. Cornerstone 2009, 9, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stierman, B.; Afful, J.; Carroll, M.D.; Te-Ching, C.; Orlando, D.; Fink, S.; Fryar, C.D.; Stierman, B.; Chen, T.-C.; Davy, O.; et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017-March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files-Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. National Health Statistics Reports, 2021, Article 158. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/106273 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- GBD 2021 US Obesity Forecasting Collaborators. National-level and state-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults in the USA, 1990–2021, and forecasts up to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 2278–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombrowski, S.U.; Knittle, K.; Avenell, A.; Araújo-Soares, V.; Sniehotta, F.F. Long term maintenance of weight loss with non-surgical interventions in obese adults: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2014, 348, g2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, P.S.; Wing, R.R.; Davidson, T.; Epstein, L.; Goodpaster, B.; Hall, K.D.; Levin, B.E.; Perri, M.G.; Rolls, B.J.; Rosenbaum, M.; et al. NIH working group report: Innovative research to improve maintenance of weight loss. Obesity 2015, 23, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, J.; Silva, M.N.; Vieira, P.N.; Carraça, E.V.; Andrade, A.M.; Coutinho, S.R.; Sardinha, L.B.; Teixeira, P.J. Motivational “spill-over” during weight control: Increased self-determination and exercise intrinsic motivation predict eating self-regulation. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Carraça, E.V.; Marques, M.M.; Rutter, H.; Oppert, J.-M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Lakerveld, J.; Brug, J. Successful behavior change in obesity interventions in adults: A systematic review of self-regulation mediators. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annesi, J.J. Behavioral weight loss and maintenance: A 25-year research program informing innovative programming. Perm. J. 2002, 26, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenders, P.G.; van Strien, T. Emotional eating, rather than lifestyle behavior, drives weight gain in a prospective study in 1562 employees. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 53, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, V.; Abbott, S. Emotional eating among adults with healthy weight, overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 36, 1922–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Péneau, S.; Ménard, E.; Méjean, C.; Bellisle, F.; Hercberg, S. Sex and dieting modify the association between emotional eating and weight status. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Ang, X.Q.; Giles, E.L.; Traviss-Turner, G. Emotional eating interventions for adults living with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, H.S.J.; Lau, S.T.; Lau, Y. Weight-loss interventions for improving emotional eating among adults with high body mass index: A systematic review with meta-analysis and meta-regression. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2022, 30, 304–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. Returning to emotional eating: The emotional eating scale psychometric properties and associations with body image flexibility and binge eating. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2015, 20, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, S.; Levy, S.; Goldzweig, G.; Hamdan, S.; Manor, A.; Dahan, S.; Rothschild, E.; Stukalin, Y.; Abu-Abeid, S. Psychological distress among bariatric surgery candidates: The roles of body image and emotional eating. Clin. Obes. 2019, 9, e12298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F. The influence of sociocultural factors on body image: Searching for constructs. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2005, 12, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, G.A.; Kim, K.K.; Wilding, J.P.H.; World Obesity Federation. Obesity: A chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, A.; Williams, G.; Fruhbeck, G. Social and Psychological Factors in Obesity. In Obesity: Science to Practice; Williams, G., Fruhbeck, G., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 347–366. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Frayn, M.; Knäuper, B. Emotional eating and weight in adults: A review. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arent, S.M.; Walker, A.J.; Arent, M.A. The Effects of Exercise on Anxiety and Depression. In Handbook of Sport Psychology, 4th ed.; Tennenbaum, G., Eklund, R.C., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 872–890. [Google Scholar]

- Schnoll, R.; Zimmerman, B.J. Self-regulation training enhances dietary self-efficacy and dietary fiber consumption. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2001, 101, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.; Grilo, C.M.; Masheb, R.M.; White, M.A. Psychological and behavioral correlates of excess weight: Misperception of obese status among persons with class II obesity. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2010, 43, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnow, B.; Kenardy, J.; Agras, W.S. The Emotional Eating Scale: The development of a measure to assess coping with negative affect by eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1995, 18, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, V.; Castellini, G.; Lo Sauro, C.; Ravaldi, C.; Lapi, F.; Mannucci, E.; Rotella, C.M.; Faravelli, C. Correlations between binge eating and emotional eating in a sample of overweight subjects. Appetite 2009, 53, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cash, T.F. The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire Users’ Manual, 3rd ed.; Old Dominion University: Norfolk, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, T.F. Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ). In Encyclopedia of Feeding and Eating Disorders; Wade, T., Ed.; Springer: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- de Zwaan, M.; Georgiadou, E.; Stroh, C.E.; Teufel, M.; Köhler, H.; Tengler, M.; Müller, A. Body image and quality of life in patients with and without body contouring surgery following bariatric surgery: A comparison of pre- and post-surgery groups. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, D.M.; Heuchert, J.W.P. Profile of Mood States Technical Update; Multi-Health Systems: North Tonawanda, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McNair, D.M.; Lorr, M.; Droppleman, L.F. Manual for the Profile of Mood States; Education and Industrial Testing Service: San Diego, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M.M.; Abrams, D.B.; Niaura, R.S.; Eaton, C.A.; Rossi, J.S. Self-efficacy in weight management. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, G.E.; Heckman, M.G.; Grothe, K.B.; Clark, M.M. Eating self-efficacy: Development of a short-form WEL. Eat. Behav. 2012, 13, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warziski, M.; Sereika, S.M.; Styn, M.A.; Music, E.; Burke, L.E. Changes in self-efficacy and dietary adherence: The impact on weight loss in the PREFER study. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 31, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godin, G. The Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire. Health Fit. J. Can. 2011, 4, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amireault, S.; Godin, G. The Godin-Shephard Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire: Validity evidence supporting its use for classifying healthy adults into active and insufficiently active categories. Percept. Mot. Skills 2015, 120, 604–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amireault, S.; Godin, G.; Lacombe, J.; Sabiston, C.M. Validation of the Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire classification coding system using accelerometer assessment among breast cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2015, 9, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D.R.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Hartman, T.J.; Leon, A.S. A simultaneous evaluation of 10 commonly used physical activity questionnaires. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1993, 25, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.J.; Freedson, P.S.; Kline, G.M. Comparison of activity levels using Caltrac accelerometer and five questionnaires. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.A.; FitzGerald, S.J.; Gregg, E.W.; Joswiak, M.L.; Ryan, W.J.; Suminski, R.R.; Utter, A.C.; Zmuda, J.M. A collection of physical activity questionnaires for health-related research. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1997, 29, S1–S205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Annesi, J.J.; Marti, C.N. Path analysis of exercise treatment-induced changes in psychological factors leading to weight loss. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1081–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vohs, K.D.; Baumeister, R.F. (Eds.) Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Application, 3rd ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, V.L.; Skinner, C.S. The Health Belief Model. In Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5th ed.; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K.V., Eds.; Jossey-Bass/Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Permanente Health Education Services. Cultivating Health Weight Management Kit, 9th ed.; Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of the Northwest: Portland, OR, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- White, I.R.; Horton, N.J.; Carpenter, J.; Pocock, S.J. Strategy for intention to treat data in randomized trials with missing outcome data. BMJ 2011, 342, d40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Song, P.X.-K. EM algorithm in Gaussian copula with missing data. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2016, 101, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.J.; Rubin, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.G.; Kim, R.S.; Aloe, A.M.; Becker, B.J. Extracting the variance inflation factor and other multicollinearity diagnostics from typical regression results. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 39, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais, D.C.; Lyles, C.; Crepaz, N.; TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devonport, T.J.; Nicholls, W.; Fullerton, C.A. systematic review of the association between emotions and eating behaviour in normal and overweight adult populations. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, N.; de Man, A.F. Weight status and body image satisfaction in adult men and women. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2010, 12, 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- Green, L.W.; Sim, L.; Breiner, H. (Eds.) Evaluating Obesity Prevention Efforts: A Plan for Measuring Progress; Institute of Medicine of the National Academies: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, R. Interpersonal Expectations: Effects of the Experimenter’s Hypothesis. In Artifacts in Behavioral Research; Rosenthal, R., Rosnow, R.L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 2009; pp. 138–210. [Google Scholar]

- Spinosa, J.; Christiansen, P.; Dickson, J.M.; Lorenzetti, V.; Hardman, C.A. From socioeconomic disadvantage to obesity: The mediating role of psychological distress and emotional eating. Obesity 2019, 27, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Effect for Time | Baseline | Month 6 | ΔBaseline−Month 6 | Group × Time Effect | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Group | F(1, 75) | p | η2p | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | d | F(1, 75) | p | η2p |

| Body satisfaction | 32.17 | <0.001 | 0.30 | 22.85 | <0.001 | 0.23 | |||||||

| TARGETED | 5.23 | 1.96 | 8.07 | 2.67 | 2.84 | 2.30 | 1.23 | ||||||

| STANDARD | 6.09 | 1.88 | 6.33 | 2.58 | 0.24 | 2.44 | 0.10 | ||||||

| Aggregated data | 5.60 | 1.96 | 7.32 | 2.76 | 1.73 | 2.68 | 0.65 | ||||||

| Emotional eating | 82.67 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 16.23 | <0.001 | 0.18 | |||||||

| TARGETED | 29.39 | 8.10 | 18.00 | 8.52 | −11.39 | 8.05 | 1.41 | ||||||

| STANDARD | 24.52 | 11.18 | 20.12 | 9.25 | −4.39 | 6.78 | 0.65 | ||||||

| Aggregated data | 27.30 | 9.78 | 18.91 | 8.85 | −8.39 | 8.26 | 1.02 | ||||||

| Negative mood | 61.39 | <0.001 | 0.45 | 14.79 | <0.001 | 0.17 | |||||||

| TARGETED | 23.27 | 13.00 | 6.04 | 11.56 | −17.24 | 13.42 | 1.28 | ||||||

| STANDARD | 21.91 | 11.80 | 16.02 | 10.76 | −5.88 | 11.95 | 0.49 | ||||||

| Aggregated data | 22.69 | 12.44 | 10.32 | 12.21 | −12.37 | 13.93 | 0.89 | ||||||

| Self-efficacy for eating | 69.70 | <0.001 | 0.48 | 15.62 | <0.001 | 0.17 | |||||||

| TARGETED | 21.95 | 6.63 | 32.62 | 6.72 | 10.66 | 7.67 | 1.39 | ||||||

| STANDARD | 22.58 | 8.41 | 26.39 | 7.80 | 3.81 | 7.33 | 0.52 | ||||||

| Aggregated data | 22.22 | 7.40 | 29.95 | 7.79 | 7.73 | 8.22 | 0.94 | ||||||

| Physical activity (METs/week) | 150.33 | <0.001 | 0.67 | 17.78 | <0.001 | 0.19 | |||||||

| TARGETED | 7.25 | 6.60 | 30.47 | 14.17 | 23.22 | 13.79 | 1.65 | ||||||

| STANDARD | 7.70 | 7.55 | 19.03 | 10.06 | 11.33 | 9.77 | 1.16 | ||||||

| Aggregated data | 7.44 | 6.98 | 25.56 | 13.74 | 18.12 | 13.52 | 1.34 | ||||||

| Self-regulating eating | 69.98 | <0.001 | 0.48 | 8.21 | 0.005 | 0.10 | |||||||

| TARGETED | 19.04 | 4.37 | 25.47 | 3.02 | 6.44 | 5.39 | 1.19 | ||||||

| STANDARD | 16.97 | 4.95 | 20.12 | 4.96 | 3.15 | 4.36 | 0.72 | ||||||

| Aggregated data | 18.15 | 4.71 | 23.18 | 4.76 | 5.03 | 5.21 | 0.97 | ||||||

| Weight (kg) | 75.87 | <0.001 | 0.50 | 19.79 | <0.001 | 0.21 | |||||||

| TARGETED | 103.18 | 8.19 | 98.15 | 7.83 | −5.04 | 3.53 | 1.43 | ||||||

| STANDARD | 96.21 | 8.77 | 94.58 | 8.24 | −1.63 | 3.02 | 0.54 | ||||||

| Aggregated data | 100.19 | 9.08 | 96.62 | 8.15 | −3.58 | 3.71 | 0.96 | ||||||

| Baseline | Month 12 | ΔBaseline−Month 12 | |||||||||||

| Weight (kg) | 26.48 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 14.60 | <0.001 | 0.16 | |||||||

| TARGETED | 103.18 | 8.19 | 98.40 | 8.24 | −4.79 | 4.01 | 1.19 | ||||||

| STANDARD | 96.21 | 8.77 | 95.50 | 8.98 | −0.71 | 5.36 | 0.13 | ||||||

| Aggregated data | 100.19 | 9.08 | 97.16 | 8.63 | −3.04 | 5.03 | 0.60 | ||||||

| Baseline | Month 24 | ΔBaseline−Month 24 | |||||||||||

| Weight (kg) | 8.10 | 0.006 | 0.10 | 8.46 | 0.005 | 0.10 | |||||||

| TARGETED | 103.18 | 8.19 | 98.27 | 11.45 | −4.91 | 8.59 | 0.57 | ||||||

| STANDARD | 96.21 | 8.77 | 96.26 | 9.23 | 0.05 | 5.43 | −0.10 | ||||||

| Aggregated data | 100.19 | 9.08 | 97.41 | 10.54 | −2.78 | 7.77 | 0.36 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Annesi, J.J.; Bakhshi, M. Emotional Eating Associated with Poor Body Satisfaction in Women with Obesity: Theory-Based Psychosocial Mediators in Weight Management Treatment. Women 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/women6010003

Annesi JJ, Bakhshi M. Emotional Eating Associated with Poor Body Satisfaction in Women with Obesity: Theory-Based Psychosocial Mediators in Weight Management Treatment. Women. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/women6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnnesi, James J., and Maliheh Bakhshi. 2026. "Emotional Eating Associated with Poor Body Satisfaction in Women with Obesity: Theory-Based Psychosocial Mediators in Weight Management Treatment" Women 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/women6010003

APA StyleAnnesi, J. J., & Bakhshi, M. (2026). Emotional Eating Associated with Poor Body Satisfaction in Women with Obesity: Theory-Based Psychosocial Mediators in Weight Management Treatment. Women, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/women6010003