Abstract

Aromatherapy, the therapeutic use of essential oils, is increasingly recognized as a complementary approach to women’s mental health, particularly during hormonally sensitive life stages such as menstruation, pregnancy, postpartum, and menopause. Concerns about the side effects of pharmacological treatments during these periods have driven interest in non-pharmacologic interventions. This narrative review synthesizes current clinical evidence on the efficacy of aromatherapy in alleviating psychological distress in women. A comprehensive literature review between 2000 and 2025 across PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases identified 47 studies focusing on essential oils for anxiety, depression, or stress in female populations. The most substantial evidence supports the use of lavender, bergamot, rose, chamomile, clary sage, and ylang-ylang, with inhalation and massage as the most frequently studied delivery methods. Outcomes include reductions in cortisol, heart rate, and subjective stress, along with improvements in mood and emotional regulation. Aromatherapy demonstrates particular promise in postpartum and perimenopausal care. However, methodological heterogeneity and variability in oil composition limit generalizability. Despite these challenges, the evidence suggests that aromatherapy may serve as a safe, low-cost adjunct for managing mood disorders and stress in women, particularly when integrated into personalized, holistic care strategies.

1. Introduction

Women across all life stages—from adolescence to menopause and beyond—face unique mental health challenges shaped by complex interactions of hormonal fluctuations, psychosocial stressors, and societal expectations [1]. Conditions such as anxiety, depression, and chronic stress disproportionately affect women and are often underdiagnosed or undertreated, especially during sensitive periods like pregnancy, the postpartum phase, and menopause. While pharmacological interventions remain the standard of care, concerns about side effects, long-term dependence, and safety during pregnancy or breastfeeding have driven growing interest in non-pharmacologic, holistic approaches [2,3].

Aromatherapy, the therapeutic use of essential oils derived from aromatic plants, has emerged as a widely accessible and culturally adaptable complementary therapy [4]. With roots in traditional healing practices, aromatherapy is now increasingly integrated into integrative medicine and mental health care [4]. Its appeal lies not only in its sensory and emotional resonance but also in preliminary scientific evidence suggesting that certain essential oils may exert measurable effects on mood, neuroendocrine responses, and autonomic nervous system regulation [5].

Aromatherapy is inherently a holistic, individualized treatment modality, as it combines physiological and psychological mechanisms of action. The effects of essential oils can vary significantly between individuals due to factors such as genetic differences in olfactory receptor sensitivity, personal scent preferences, cultural associations, and psychological expectations. This variability presents both opportunities and challenges for integrating aromatherapy into evidence-based mental health care.

A growing number of essential oils have been explored for their impact on emotional regulation and stress resilience, particularly in female populations. Essential oils such as lavender, bergamot, rose, chamomile, clary sage, and ylang-ylang are frequently used for their calming, mood-stabilizing, or uplifting effects. These plant-based interventions have been tested in various clinical settings, often delivered through inhalation or massage, and are reported to ease symptoms of anxiety, low mood, and psychological tension. Their relevance is especially pronounced during hormonally dynamic life stages, such as the postpartum period or menopause, where emotional vulnerability is heightened, and conventional treatments may be less accessible or desirable.

Taken together, anxiety, depression, and stress are interrelated conditions that share overlapping biological mechanisms, including hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation, altered neurotransmitter activity, and autonomic imbalance [6,7]. Aromatherapy offers a unique intersection with these pathways by simultaneously reducing physiological arousal, modulating mood-related neurochemistry, and fostering psychosocial resilience through ritual and self-care. This integrated framework positions aromatherapy as a relevant adjunctive strategy for women’s mental health, where these conditions frequently co-occur and reinforce one another.

This review aims to critically assess the therapeutic potential and constraints of aromatherapy, situating it within a broader context of integrative approaches to women’s mental health. By aligning current evidence with patient-centered care models, the review seeks to inform future clinical practice and research, particularly in comparison to other non-pharmacological strategies such as mindfulness, acupuncture, and lifestyle interventions.

2. Search Results and Study Selection

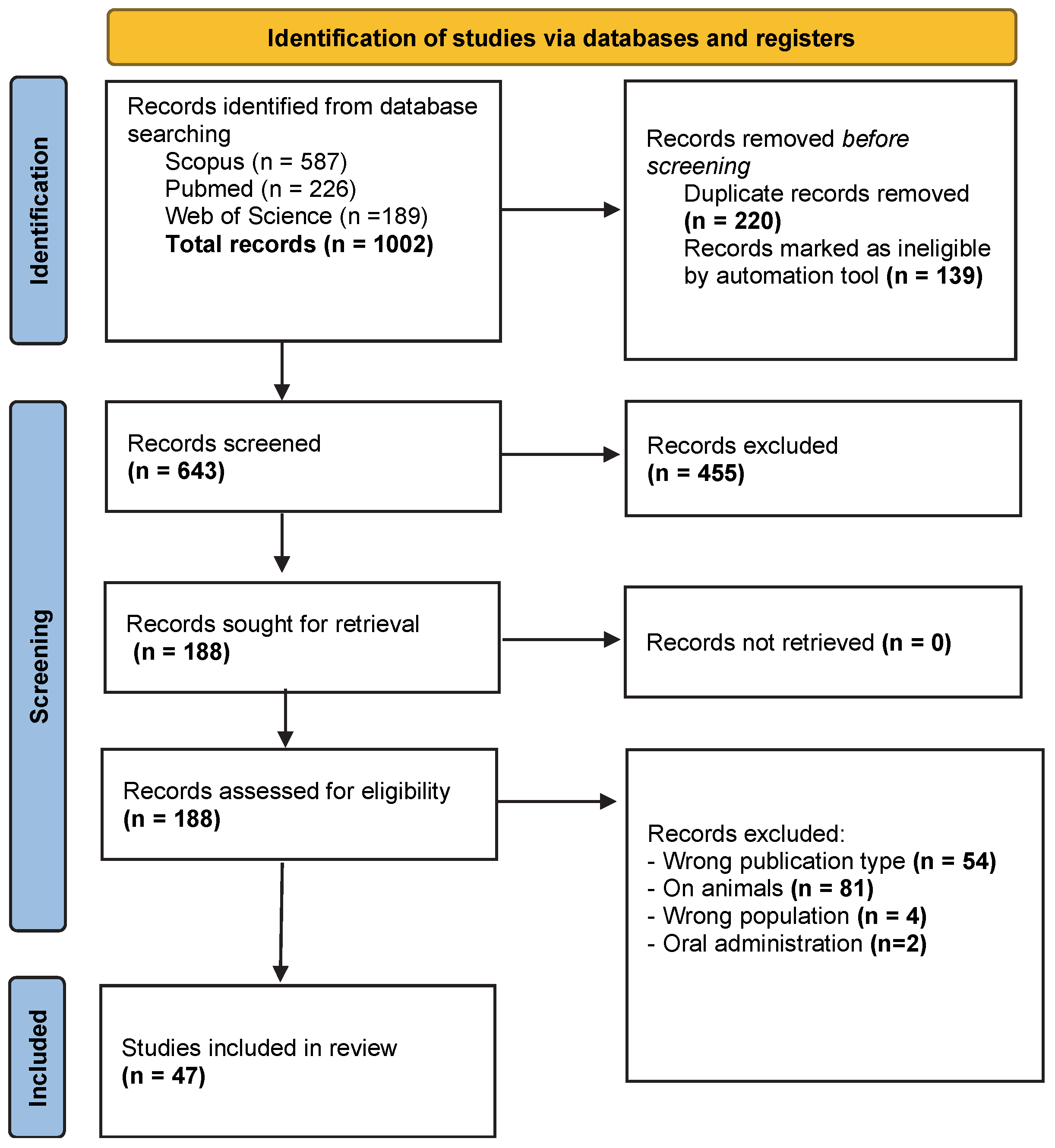

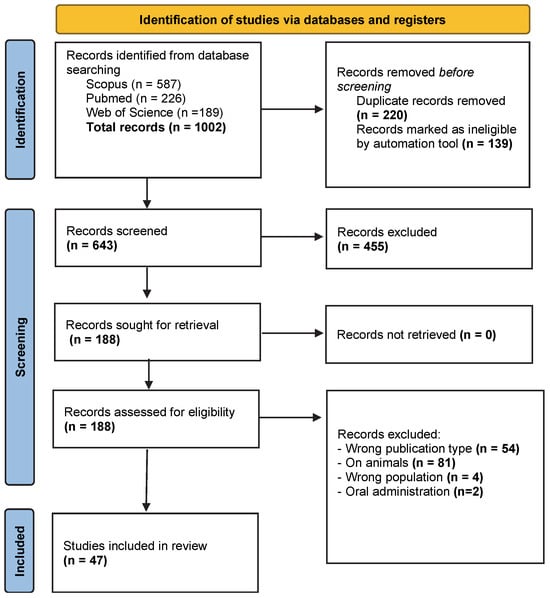

The results presented in this section refer to the literature search and study selection process rather than the clinical outcomes of the included studies. Search results (.ris format) were exported in .ris format and imported into the Rayyan web tool for systematic reviews [8]. Although Rayyan is frequently used in systematic reviews, in the present narrative review, it was employed solely as a practical tool to organize records, remove duplicates, and facilitate transparent screening, without applying a formal systematic review protocol. The search was executed across the selected databases, initially retrieving 1002 articles. All extracted references were added to a PubMed collection and exported to Rayyan for title and abstract screening. Duplicate articles were removed, and records marked as ineligible by the automation tool were removed, resulting in a preliminary pool of 643 unique articles.

Titles and abstracts of the articles were reviewed to identify potentially relevant studies. Articles irrelevant to the research topic were excluded at this stage, leading to a refined set of 188 articles. Full-text access to these articles was obtained through institutional subscriptions and, when necessary, interlibrary loan services. The search process and article inclusion were documented and tracked using reference management software. The entire search process is summarized in a flowchart (Figure 1) that illustrates the number of articles identified, screened, and included at each stage, as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [9].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the identification, screening, and inclusion process for studies evaluating the clinical use of essential oils (aromatherapy) in managing women’s mental health conditions, including anxiety, depression, and stress. Studies were excluded under “wrong publication type/study design” if they were non-original articles (e.g., reviews, editorials, commentaries), not peer-reviewed, conducted in vitro or in vivo without human participants, or did not include empirical clinical data relevant to women’s mental health outcomes.

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 47 clinical studies met eligibility requirements and were included in this review. These studies encompass a wide range of essential oils, delivery methods, and mental health outcomes, providing a robust yet heterogeneous evidence base.

3. Mechanisms of Action in Aromatherapy

3.1. Neurobiological Basis (Olfactory Pathways and Limbic System Activation)

Aromatherapy exerts its psychological and physiological effects primarily through the olfactory system, which plays a direct and powerful role in modulating mood, memory, and emotion [10]. The neurobiological basis for aromatherapy’s impact on mental health lies in the unique structure of the olfactory pathway and its direct connection to the brain’s limbic system, particularly the amygdala, hippocampus, and hypothalamus—key regions involved in emotional regulation and the stress response [11].

3.1.1. Olfactory Signal Transduction

When aromatic molecules are inhaled, they travel through the nasal cavity and interact with olfactory receptor neurons located in the olfactory epithelium. These neurons express highly sensitive, diverse odorant receptors, enabling them to detect a wide range of volatile organic compounds found in essential oils [12,13].

3.1.2. Limbic System and Emotional Regulation

The limbic system, particularly the amygdala and hippocampus, plays a central role in the regulation of emotions, fear, memory, and mood—all of which are directly relevant to anxiety, depression, and stress disorders. The amygdala is involved in threat detection and the formation of emotional memories, while the hippocampus contributes to the consolidation of memories and contextual interpretation of experiences [14,15].

When essential oils are inhaled, their aromatic molecules can influence the release of neurotransmitters and neural activity within these limbic structures [16]. For instance, studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalography have shown that specific essential oils can increase activity in brain regions associated with relaxation, calmness, and a positive effect. Lavender essential oil, for example, has been found to modulate amygdala activity and promote parasympathetic nervous system dominance, leading to a lowered heart rate and reduced cortisol levels [17,18].

3.1.3. Hypothalamus and Neuroendocrine Modulation

The hypothalamus, also part of the limbic system, plays a vital role in maintaining homeostasis and regulating the HPA axis, the body’s central stress response system [19]. Olfactory stimulation with essential oils may influence hypothalamic activity and, in turn, modulate the release of stress-related hormones such as cortisol, adrenaline, and norepinephrine. This mechanism is particularly relevant in managing chronic stress and anxiety-related disorders in women, who may exhibit heightened HPA axis sensitivity during key hormonal transitions (e.g., premenstrual phase, postpartum, perimenopause) [20,21].

3.1.4. Neuroplasticity and Long-Term Effects

Emerging evidence suggests that repeated exposure to pleasant or therapeutic scents may also contribute to neuroplastic changes in the brain, particularly in pathways associated with emotional learning and memory. This raises the possibility that aromatherapy, when used consistently and intentionally, could have cumulative and sustained effects on mood regulation over time [10,22].

Upon activation, these olfactory neurons send electrical signals to the olfactory bulb, a structure situated at the base of the brain. From here, signals are rapidly transmitted to multiple regions of the brain, bypassing the thalamus (the usual sensory relay station). This direct route to the limbic system allows scent to evoke immediate emotional responses and autonomic changes—such as shifts in heart rate, blood pressure, and hormone levels—often before the conscious brain has even processed the odor [23].

3.2. Neurochemical Effects of Essential Oils in Mental Health

Beyond olfactory-limbic pathways, the therapeutic potential of aromatherapy in mental health is also mediated by its impact on neurochemical systems, including those involved in mood regulation, arousal, and stress response [16]. Several essential oils have been shown, through both preclinical and clinical research, to interact with neurotransmitter systems, including GABAergic, serotonergic, dopaminergic, and noradrenergic pathways, thereby contributing to their anxiolytic, antidepressant, and calming properties.

3.2.1. GABAergic Modulation

One of the most well-studied mechanisms involves the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system, which plays a central role in reducing neuronal excitability and inducing relaxation [24]. Certain essential oil constituents—most notably linalool and linalyl acetate, found in lavender (Lavandula angustifolia)—have demonstrated GABA receptor affinity in animal models [25,26]. These compounds are believed to enhance GABAergic transmission, leading to sedative and anxiolytic effects [27].

3.2.2. Serotonergic Pathways

Serotonin (5-HT) is a key neurotransmitter involved in maintaining mood balance and regulating emotions [28]. Although more research is needed, some essential oils—such as bergamot and citrus essential oils—have been suggested to influence serotonergic pathways. Preclinical data indicate that limonene (a major component of citrus essential oils) may enhance serotonin availability or receptor sensitivity, potentially improving mood and reducing depressive symptoms [29,30,31,32].

In addition, studies on rose essential oil and clary sage indicate antidepressant-like effects possibly linked to serotonergic mechanisms, although direct receptor studies in humans remain limited [33,34].

3.2.3. Dopaminergic and Noradrenergic Effects

The dopamine and norepinephrine systems are associated with motivation, alertness, and energy levels—all commonly disrupted in depressive and stress-related disorders. Essential oils such as peppermint, rosemary, and eucalyptus have been linked to enhanced alertness and cognitive performance, possibly through mild stimulation of the catecholaminergic system [16,35].

Inhalation of these essential oils may increase wakefulness and improve mental clarity, which could be beneficial in managing fatigue-related aspects of depression or chronic stress. However, the exact neurochemical interactions remain under-researched in human populations.

3.2.4. Endocrine and Hormonal Interactions

Essential oils may also exert indirect neurochemical effects by modulating hormonal systems that influence mood and emotional well-being [11]. For example, clary sage has been associated with changes in cortisol levels and has shown promise for supporting mood during menopause and the postpartum period [36]. Some essential oils may interact with estrogen or oxytocin pathways, influencing emotional bonding, relaxation, and overall well-being; however, this area requires further empirical exploration [11,37].

3.3. Physiological Effects of Aromatherapy in Mental Health

Aromatherapy influences not only the brain and neurotransmitter systems but also has measurable effects on physiological indicators associated with stress, anxiety, and emotional regulation. These include autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity, cardiovascular responses, and neuroendocrine markers, particularly cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone [16,38].

3.3.1. Autonomic Nervous System Regulation

The autonomic nervous system, comprising the sympathetic (fight-or-flight) and parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) branches, plays a central role in how the body responds to emotional stimuli [39]. Several studies indicate that aromatherapy may help rebalance ANS activity, promoting parasympathetic dominance—associated with relaxation and recovery—while downregulating excessive sympathetic activation linked to anxiety and stress [40,41].

Inhalation of specific essential oils—particularly lavender, bergamot, and ylang-ylang—has been shown to reduce heart rate and blood pressure in both healthy individuals and patients in clinical settings (e.g., preoperative environments, postpartum recovery, and stress-inducing tasks) [4,42,43]. These changes often occur within minutes of exposure and may reflect reduced physiological arousal and improved emotional regulation.

3.3.2. Heart Rate Variability (HRV)

Heart rate variability (HRV), a sensitive measure of ANS balance and resilience, is increasingly used in aromatherapy research. Higher HRV reflects better stress adaptation and stronger parasympathetic activity [44]. Studies suggest that aromatherapy—especially when combined with massage or mindfulness-based interventions—may enhance HRV, indicating improved stress tolerance and emotional stability [45,46].

For example, research involving the inhalation of lavender and sandalwood essential oils during guided relaxation exercises has demonstrated improvements in HRV metrics among women with generalized anxiety or caregiver stress [47,48,49].

3.3.3. Cortisol and Neuroendocrine Markers

Cortisol is a key biomarker of stress, regulated via the HPA axis. Dysregulation of cortisol rhythms is commonly observed in individuals with chronic stress, depression, and anxiety disorders [50,51]. Several clinical studies have reported that aromatherapy—whether by inhalation or topical application—can significantly reduce salivary or serum cortisol levels, particularly after acute stress [52].

Studies involving female workers found that inhaling bergamot essential oil in workplace settings led to significant reductions in salivary cortisol and self-reported tension compared with control conditions with no aromatherapy or placebo exposure [53,54]. A clinical study involving menopausal women in their 50s found that inhalation of clary sage essential oil led to a significant reduction in cortisol levels (31–36% decrease), along with increases in serum serotonin (5-HT)—evidence of antidepressant-like neuroendocrine effects [36]. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving healthy postmenopausal women, daily inhalation of 0.1% or 0.5% neroli essential oil for 5 days resulted in reduced systolic and diastolic blood pressure, with a trend toward reduced serum cortisol levels, supporting its use in alleviating menopausal stress symptoms [55]. Another RCT conducted during labor showed neroli inhalation significantly reduced anxiety, indirectly suggesting physiological stress reduction via endocrine modulation [56].

3.3.4. Other Physiological Indicators

Additional physiological benefits of aromatherapy reported in the literature include:

- Improved respiratory rate and oxygen saturation during stress or panic episodes [57].

- Reduced muscle tension, particularly with oils used in massage (e.g., marjoram, chamomile) [58].

- Improved sleep architecture, with decreased night-time awakenings and longer deep sleep cycles following lavender exposure [59].

These findings suggest that aromatherapy not only alters subjective emotional states but also creates objective, measurable changes in physiological functioning, which may contribute to its therapeutic effects in mental health contexts.

3.4. Psychosocial Mechanisms of Aromatherapy in Mental Health

While biological and neurochemical mechanisms provide a foundation for understanding how aromatherapy may influence mental health, psychosocial factors also play a significant and often underappreciated role in its perceived and actual effectiveness. These mechanisms include the influence of ritual, relaxation response, expectancy effects, and the broader context in which aromatherapy is delivered. Together, these factors help explain how aromatherapy can benefit emotional well-being, even when its direct biochemical effects are modest.

3.4.1. The Therapeutic Power of Ritual

The use of aromatherapy often involves structured and intentional practices, such as preparing a diffuser, applying oils through massage, or engaging in self-care routines. These repeated actions can function as rituals, which have been shown to enhance psychological stability and create a sense of control, predictability, and safety. In the context of stress, anxiety, or depression—conditions often characterized by feelings of chaos or overwhelm—such rituals can foster a calming psychological environment that enhances the overall therapeutic effect [60,61].

For many women, aromatherapy rituals are integrated into daily or weekly self-care practices, especially during times of hormonal fluctuation (e.g., menstruation, postpartum, perimenopause) or emotional strain. These rituals not only mark transitions or boundaries in the day (e.g., winding down before sleep) but also serve as symbolic acts of self-nurturing, which can be intrinsically healing [62,63].

3.4.2. Induction of the Relaxation Response

Engaging in aromatherapy often involves intentional relaxation practices, such as deep breathing, mindfulness, quiet rest, or gentle massage. These activities independently activate the relaxation response, a physiological state that counters the stress-induced activation of the sympathetic nervous system. This mind–body synergy may amplify the benefits of essential oils by enhancing parasympathetic activity, reducing muscle tension, and lowering emotional reactivity [64].

In clinical settings, the context in which aromatherapy is delivered—whether during a therapeutic massage, in a calm hospital room, or as part of a guided meditation session—can significantly influence outcomes. This interaction between environment and therapy underlines the importance of holistic treatment design when using aromatherapy in mental health interventions.

3.4.3. Expectation and Placebo Effects

Like many complementary therapies, aromatherapy may produce measurable improvements in mood and stress through expectancy effects—the belief that the intervention will be beneficial. A lab-based placebo-controlled study found that expectations alone—rather than the scent—affected relaxation responses after stress (e.g., ERP patterns) [65]. Although aromatherapy shows moderate efficacy for anxiety and depression in meta-analyses [66], much of this benefit may derive from psychosocial and sensory rituals, rather than oil pharmacology. Placebo effects, particularly relevant to sensory and self-care interventions, involve complex brain-body interactions—including the activation of the reward system and mood-regulating neurotransmitter pathways—and can be symbolically meaningful, especially in women’s mental health contexts, where meaning, perception, and lived experience play a central role [67].

4. Therapeutic Essential Oils: Mechanisms and Clinical Evidence

Essential oils represent the cornerstone of aromatherapy and have been increasingly investigated for their potential to support emotional well-being and mental health in women. Among the numerous plant-derived essential oils available, a select group—particularly lavender, bergamot, rose, ylang-ylang, clary sage, and chamomile—has shown the most consistent evidence in clinical and preclinical research. These essential oils exhibit multifaceted mechanisms of action, combining neurobiological, neuroendocrine, and psychosocial pathways that together influence stress reactivity, mood regulation, and emotional resilience.

The therapeutic effects of essential oils arise from the interaction of volatile aromatic compounds with olfactory and limbic brain regions, modulation of neurotransmitter systems (such as GABAergic and serotonergic networks), and activation of the parasympathetic nervous system [16]. In women, these effects may be further shaped by hormonal status, life stage, and psychosocial context, making aromatherapy an adaptable intervention for conditions such as anxiety, depression, and chronic stress.

4.1. Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia)

Lavender essential oil is the most extensively researched botanical in aromatherapy and mental health. Its calming and anxiolytic properties have been recognized for centuries, and contemporary research has confirmed its neurophysiological and endocrine effects [68]. The essential oil’s principal constituents—linalool and linalyl acetate—contribute to its sedative and mood-stabilizing activity through GABA receptor modulation, serotonergic regulation, and autonomic nervous system balance [17,69].

4.1.1. Mechanisms of Action

Lavender interacts with central nervous system pathways that regulate stress and emotional arousal. Preclinical and neuroimaging studies indicate that inhaled lavender reduces amygdala activation and enhances parasympathetic dominance, resulting in lower heart rate and cortisol levels. Its constituents bind to GABA_A receptors, exerting mild inhibitory effects. Additionally, lavender’s serotonergic modulation may contribute to its antidepressant effects, while reductions in sympathetic nervous system activity support relaxation and improved sleep quality.

It is important to note that the chemical composition of L. angustifolia essential oil can vary considerably depending on cultivar and distillation parameters [70]. While linalool and linalyl acetate are typically the dominant sedative constituents, varying amounts of camphor and eucalyptol may also be present and can influence the overall pharmacological profile, potentially accounting for differences observed across studies.

4.1.2. Clinical Evidence

Multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses demonstrate lavender’s efficacy in alleviating anxiety, depressive symptoms, and physiological stress markers in women.

- Anxiety: Inhalation of lavender essential oil before surgical or obstetric procedures significantly reduced preoperative anxiety and salivary cortisol levels compared with controls [71]. In postpartum women, regular lavender inhalation for four weeks lowered anxiety scores and improved sleep quality [72,73,74].

- Depression: Inhaled preparations of lavender essential oil have demonstrated meaningful reductions in depressive symptoms in individuals with mild to moderate depression, with reported improvements in mood, sleep quality, and overall emotional well-being, and with a favorable safety and tolerability profile [75,76].

- Stress: A study involving women undergoing surgery found that preoperative inhalation of lavender significantly reduced anxiety levels. Participants who inhaled lavender essential oil for 30 min before entering the operating room had lower Visual Analog Scale scores than those who received standard care [77].

Collectively, evidence supports lavender as a safe, low-risk intervention for anxiety, situational stress, and mood dysregulation in women, particularly during hormonally sensitive stages such as the postpartum or perimenopausal periods.

4.1.3. Safety and Use

Lavender is well tolerated when used through inhalation or diluted topical application (1–3% in carrier oil). Adverse reactions are rare and typically limited to mild skin irritation. Its broad safety profile, pleasant aroma, and rapid onset of psychological benefits make lavender one of the most accessible and evidence-based essential oils for women’s mental health care [78].

4.2. Bergamot (Citrus bergamia)

Bergamot essential oil, extracted from the rind of the Citrus bergamia fruit, is highly valued in aromatherapy for its uplifting yet calming properties. With a fresh, citrusy scent and a mild floral undertone, bergamot has been widely studied for its potential anxiolytic, antidepressant, and stress-relieving effects. It is commonly used in both clinical and home settings to reduce emotional tension and improve mood, making it particularly relevant for women experiencing situational or chronic psychological distress [79].

4.2.1. Mechanisms of Action

The primary active constituents of bergamot, limonene, linalool, and linalyl acetate, are believed to interact with neurochemical systems that regulate mood and arousal [80]. Preclinical studies indicate that these compounds may enhance serotonergic and GABAergic signaling, leading to relaxation and improved affective tone. Inhalation of bergamot vapor has also been associated with reduced cortisol secretion and autonomic nervous system arousal, supporting its capacity to counteract stress-related endocrine activation.

In addition to its neurochemical actions, bergamot exhibits antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which may indirectly benefit mental health by mitigating oxidative stress pathways linked to mood and anxiety disorders.

4.2.2. Clinical Evidence

Overall, bergamot appears to exert both rapid-onset anxiolytic effects and sustained mood-stabilizing benefits, making it a promising adjunct in integrative approaches to women’s mental well-being.

A growing body of clinical research supports bergamot’s use in mental health contexts. A randomized trial involving women preparing for laparoscopic surgery. Participants inhaled two drops of 3% bergamot essential oil and experienced significant reductions in salivary cortisol and anxiety scores compared with those who inhaled odorless oil [81].

A study also showed decreases in alpha-amylase levels, along with reduced anxiety and physiological stress markers. While exact heart rate changes were not quantified, the intervention significantly mitigated autonomic stress responses in female surgical candidates [82]. A published pilot study with primarily female participants (50 women, aged 23–70) found that 15 min bergamot inhalation led to a 17% increase in self-reported positive affect compared with controls in a mental health treatment waiting area [43]. In a RCT (2025) with 132 postmenopausal women, aromatherapy combining lavender and bergamot inhaled three times daily for 8 weeks significantly reduced anxiety scores (AMD ≈ −1.9) and depression symptoms (p = 0.011) compared to control groups, demonstrating synergistic benefits with mindfulness-based intervention [83].

4.2.3. Safety and Use

Bergamot essential oil is generally regarded as safe when used appropriately. The preferred mode of administration is inhalation, which offers immediate psychological benefits without systemic absorption. For topical use—such as in massage—it is essential to select furocoumarin-free (FCF) formulations or to avoid sunlight exposure for at least 12 h after application, as bergamot may cause phototoxic reactions. Skin irritation is rare but possible at high concentrations. Due to limited safety data in pregnancy, conservative use under professional guidance is recommended [78].

4.3. Rose (Rosa × damascena)

Rose essential oil, distilled from the petals of Rosa × damascena, has long been associated with emotional healing, femininity, and sensuality. In aromatherapy, rose essential oil is used for its antidepressant, anxiolytic, and mood-stabilizing effects, particularly in women’s health contexts such as postpartum depression, menstrual distress, and perimenopausal mood swings. Its warm, floral aroma is often described as comforting and emotionally grounding, making it a popular choice for mental and emotional support.

4.3.1. Mechanisms of Action

The therapeutic potential of rose essential oil stems from its diverse phytochemical composition, including citronellol, geraniol, nerol, and phenylethyl alcohol. These constituents exert calming and antidepressant-like effects through several neurobiological pathways [84]. Experimental studies suggest that rose essential oil modulates GABAergic and serotonergic activity, enhances parasympathetic tone, and suppresses sympathetic nervous system activation [85].

4.3.2. Clinical Evidence

Although fewer clinical trials exist than for lavender and bergamot, several well-designed studies suggest that rose essential oil may offer meaningful benefits for women’s mental health. Inhalation of rose essential oil has consistently been associated with reductions in anxiety, particularly in healthcare or perioperative settings, where participants reported lower anxiety scores and physiological markers of stress after exposure [86]. Among postpartum women, twice-weekly aromatherapy massage using a blend of rose otto and lavender essential oil over four weeks produced significantly greater reductions in depression and anxiety (EPDS, GAD-7) compared to controls [87]. For women with menstrual-related mood disorders, aromatherapy with Rosa × damascena essential oil has been shown to decrease irritability, sadness, and fatigue in randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis [88].

Collectively, these findings indicate that rose essential oil offers gentle yet meaningful psychological support across the female lifespan, particularly during periods of hormonal and emotional vulnerability.

4.3.3. Safety and Use

Rose essential oil is non-toxic, non-irritating, and generally safe when diluted adequately for inhalation or topical application. It is often blended with complementary oils such as lavender or geranium to enhance emotional balance while reducing cost, as pure rose essential oil is highly concentrated and expensive.

According to IFRA (International Fragrance Association) standards, the maximum recommended dermal concentration for Rosa × damascena essential oil is approximately 0.02–0.03%, depending on the formulation type and area of application. These limits ensure safe topical use and minimize the risk of sensitization when incorporated within professionally supervised aromatherapy protocols [89].

4.4. Ylang-Ylang (Cananga odorata)

Ylang-ylang essential oil, derived from the flowers of Cananga odorata, is renowned for its deeply floral, sweet scent and its calming, mood-lifting properties [90]. In aromatherapy, ylang-ylang is frequently used to address nervous tension, anger, low self-esteem, and stress-induced cardiovascular symptoms, with a growing body of evidence supporting its role in women’s mental and emotional health.

4.4.1. Mechanisms of Action

The therapeutic effects of ylang-ylang are attributed to its active constituents, including linalool, benzyl acetate, geranyl acetate, β-caryophyllene, and methyl benzoate [90]. These compounds have demonstrated GABAergic activity, contributing to the essential oil’s sedative and anxiolytic effects [43,91].

Additional findings suggest that ylang-ylang may influence dopaminergic pathways, contributing to improved mood, motivation, and emotional stability. Its calming yet uplifting profile reflects a balance between mild CNS relaxation and positive affective stimulation, distinguishing it from purely sedative essential oils [92].

The discussion in this review refers to C. odorata essential oil of Grade III, which is typically obtained in the later stages of distillation and contains higher proportions of sesquiterpenes such as β-caryophyllene and germacrene D, with comparatively lower levels of linalool and benzyl acetate than earlier fractions. These compositional characteristics may contribute to its balanced yet calming psychophysiological profile.

4.4.2. Clinical Evidence

Although fewer trials have been conducted post-2020, earlier clinical evidence suggests that inhaled blends containing ylang-ylang significantly lowered blood pressure, pulse rate, and cortisol levels, and that regular workplace use improved psychological well-being in women [92]. These findings suggest promising benefits for stress, anxiety, and emotional regulation, warranting further controlled trials in women’s mental health contexts.

4.4.3. Safety and Use

Ylang-ylang is generally safe when diluted properly, but should be used with care:

- Potential skin irritant in high concentrations—always dilute to 0.8–1.0% for topical use.

- May cause headaches or nausea in sensitive individuals due to its intensity.

- Not known to be contraindicated in pregnancy but should be used in low doses.

Its potent fragrance and rapid physiological impact make ylang-ylang especially useful in acute emotional distress, panic, or irritability—symptoms often heightened in hormonal or life-stage transitions in women [78].

4.5. Clary Sage (Salvia sclarea)

Clary sage essential oil, distilled from the flowering tops and leaves of Salvia sclarea, is widely used in aromatherapy for its mood-regulating, hormone-balancing, and anxiolytic properties, particularly in women’s reproductive health [93]. Known for its herbaceous, slightly floral aroma, clary sage is often incorporated into emotional support protocols during PMS, menstruation, labor, and menopause, making it highly relevant to women’s mental health.

4.5.1. Mechanisms of Action

The principal constituents of clary sage essential oil include linalyl acetate, linalool, sclareol, and geraniol, which act on both neurochemical and endocrine pathways related to mood and stress regulation. Experimental studies indicate that these compounds enhance GABAergic activity, contributing to anxiolytic and sedative effects [94].

Clary sage has also demonstrated serotonergic modulation, supporting antidepressant-like effects in preclinical models [95]. Its diterpene component, sclareol, exhibits mild phytoestrogenic properties, interacting with estrogen receptors to help stabilize mood and alleviate emotional symptoms linked to hormonal fluctuations [96]. This dual neurochemical and hormonal mechanism may explain its particular relevance for women’s mood disorders across the reproductive lifespan [97].

4.5.2. Clinical Evidence

Clinical evidence supporting the mental health benefits of clary sage essential oil is growing, particularly in women’s reproductive contexts. In menopausal women, inhalation of clary sage significantly reduced cortisol levels while enhancing serotonin concentrations, supporting mood stabilization relative to control conditions [98]. During labor, spouses’ aromatherapy massage incorporating clary sage (with lavender, frankincense, and neroli) resulted in reduced maternal pain and anxiety compared with massage alone or no massage control [99]. Pilot data from term-pregnant women also reveal post-inhalation reductions in cortisol alongside modest oxytocin changes, with high acceptability and no adverse events, underscoring early feasibility for emotional support during peripartum transitions [100].

Collectively, these findings support the use of clary sage as a safe and effective adjunct for alleviating emotional symptoms associated with hormonal transitions, combining neurochemical and endocrine mechanisms into a single therapeutic approach.

4.5.3. Safety and Use

Clary sage is considered safe when used appropriately:

- Avoid in early pregnancy but often used in late pregnancy and labor under professional supervision.

- May cause drowsiness; not recommended before driving or operating machinery.

- Rare skin sensitivity—always dilute to 1–2% for topical use [78].

Due to its dual impact on neurochemical and hormonal systems, clary sage is especially valuable for hormone-related mood disorders such as Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder, postpartum anxiety, and menopausal depression [101].

4.6. Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla)

Chamomile essential oil, derived from the flowers of German chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla), is a well-known calming agent used in traditional and modern herbal medicine. In aromatherapy, chamomile is widely used to support emotional balance, reduce anxiety, promote restful sleep, and alleviate symptoms of irritability or tension, particularly during menstrual, postpartum, or menopausal periods [102].

Its gentle, floral, apple-like aroma, combined with its sedative properties, makes chamomile a key essential oil for women’s mental health, particularly for those with sensitive constitutions, insomnia, or stress-related somatic complaints such as tension headaches or digestive discomfort.

4.6.1. Mechanisms of Action

Chamomile’s therapeutic effects derive from its diverse chemical profile, which includes bisabolol, chamazulene, and coumarins. These compounds interact with GABA_A receptors, producing mild anxiolytic and sedative effects [102]. Through inhalation, these compounds may influence emotional processing via olfactory–limbic pathways, contributing to relaxation and reduced autonomic arousal. However, unlike chamomile extracts, the essential oil lacks flavonoids and therefore does not interact with benzodiazepine-like receptors, as often reported in studies of chamomile infusions or supplements. Consequently, any anxiolytic or sedative effects associated with chamomile essential oil are expected to be subtle, indirect, and primarily mediated through sensory and autonomic mechanisms rather than direct neurochemical modulation.

In addition, chamomile exhibits strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant actions that may reduce neuroinflammation—a process increasingly recognized in mood and anxiety disorders [102].

4.6.2. Clinical Evidence

Clinical evidence supporting the use of chamomile essential oil for anxiety, stress, or mood regulation remains limited and inconsistent. Available aromatherapy studies typically report pre- and post-intervention measures of anxiety, stress, or physiological markers; however, several trials show substantial variability and overlapping standard deviations between intervention and placebo groups. As a result, observed differences are often small and of uncertain clinical significance.

For women with premenstrual mood disturbances, aromatherapy using chamomile essential oil—typically combined with inhalation or massage—has been associated with reductions in PMS-related anxiety, sadness, fatigue, and overall psychological burden compared to control interventions [103].

Overall, chamomile provides gentle yet measurable improvements in emotional regulation, anxiety reduction, and sleep, particularly suited to women who prefer non-pharmacologic, low-intensity interventions.

4.6.3. Safety and Use

Chamomile is considered one of the safest essential oils for regular use. It is non-toxic, non-irritating, and suitable for inhalation, massage, or aromatic bathing when diluted to 0.5–2% in a carrier oil [104]. German chamomile is appropriate for use during pregnancy and postpartum under professional guidance, though individuals with ragweed allergies should exercise caution due to potential cross-reactivity [105,106]. Its mild profile and high acceptance make chamomile especially beneficial for sensitive individuals or those seeking to manage stress, emotional fatigue, or insomnia through natural and gentle means.

4.7. Summary of Key Essential Oils and Clinical Applications

To better illustrate the therapeutic scope and application of essential oils in women’s mental health, Table 1 provides a comparative summary of the key essential oils discussed in this section. The table highlights their primary bioactive constituents, reported psychological benefits, proposed mechanisms of action, common modes of administration, and important safety considerations. These essential oils—chosen for their relevance in the management of anxiety, depression, and stress—represent some of the most commonly used and clinically supported agents in aromatherapeutic interventions targeting women’s mental and emotional well-being.

Table 1.

Therapeutic Profiles of Key Essential Oils for Women’s Mental Health Support.

The information summarized in Table 1 directly reflects the evidence discussed in the preceding subsections. The order of presentation and the described benefits, mechanisms, and safety considerations have been standardized to ensure consistency between the narrative and tabulated data. This alignment facilitates clearer interpretation of how each essential oil contributes to anxiety, depression, and stress management in women.

5. Methods of Delivery and Practical Use

The clinical and therapeutic benefits of essential oils for women’s mental health are deeply influenced by their delivery method, as this determines both absorption rate and neurophysiological response. Delivery methods vary widely depending on symptom profile, individual sensitivity, cultural practices, and clinical setting. This Section examines the most common routes of administration: inhalation and topical application, while also addressing practical concerns such as dosage, treatment duration, and individual preferences.

5.1. Inhalation

Inhalation is the most widely used and evidence-based method for delivering essential oils in mental health care [107]. It involves breathing in volatile compounds that travel directly via the olfactory nerve to the limbic system, the brain region responsible for emotions, memory, and autonomic regulation. This mechanism enables rapid psychological effects, often occurring within minutes.

Delivery methods:

- Diffusers (ultrasonic or nebulizing): disperse essential oils into the air and are suitable for ambient therapeutic environments (e.g., homes, clinics, birthing rooms).

- Steam inhalation involves adding essential oils to hot water and inhaling the vapors; it is often used for simultaneous respiratory support and stress relief.

- Direct inhalation: via inhaler sticks, cotton balls, or drops on clothing or pillows; ideal for acute anxiety or panic episodes.

Inhalation is favored for its ease of use, rapid onset, and minimal systemic absorption, making it especially suitable for pregnant or postpartum women, elderly individuals, and those with medication sensitivities [26].

5.2. Topical Application

Topical application allows essential oils to be absorbed through the skin, enter the bloodstream, and exert systemic effects. It is especially popular in women’s health for conditions where stress manifests physically, such as muscle tension, menstrual discomfort, or insomnia [37].

Common methods:

- Massage therapy: Essential oils are diluted in carrier oils (e.g., almond, jojoba) and massaged into the skin, often in areas of emotional or hormonal significance (e.g., the abdomen, lower back, and shoulders). Massage enhances circulation, oxytocin release, and relaxation [108].

- Aromatic baths: Essential oils are diluted in a dispersant (e.g., full-fat milk, bath gel) and added to warm water. This combines skin absorption with inhalation, offering holistic relaxation benefits [109].

- Compresses: warm or cool cloths soaked in a diluted essential oil solution, applied to the abdomen or forehead for menstrual cramps or stress-related headaches.

Topical use offers a longer duration of effect than inhalation and allows for ritualistic, embodied care practices, often important in women’s health routines.

5.3. Dosage, Duration, and Frequency

There is no universally accepted dosage standard for aromatherapy, but common clinical guidelines suggest:

- Inhalation: 1–3 drops per session, up to 3 times daily [110].

- Topical use: 1–3% dilution (5–15 drops per 30 mL carrier oil) for adults [111].

- Bathing: 5–10 drops diluted in dispersant, per bath [112].

The duration of treatment varies depending on the condition. For acute anxiety, effects may be felt within minutes to hours, while chronic mood regulation may require daily use over several weeks. Clinical studies often report benefits after 2–8 weeks of consistent use.

Practitioners should tailor protocols to the individual’s age, health status, and the severity of their condition, and always recommend patch testing for skin sensitivity before prolonged use.

5.4. Patient Preference and Cultural Relevance

The success of aromatherapy is closely tied to individual sensory responses and cultural context [35]. Scent preferences are highly personal and influenced by:

- Childhood associations.

- Cultural symbolism (e.g., rose essential oil in Middle Eastern postpartum care).

- Religious/spiritual beliefs (e.g., frankincense in Christian or ritualistic settings).

- Socioeconomic access to natural therapies.

Respecting these preferences enhances adherence and psychological receptivity to treatment. In women’s health, aromatherapy can also support ritualized self-care, reinforce agency, and restore a sense of embodied autonomy in managing mood disorders.

6. Safety, Contraindications, and Regulation

The use of essential oils in mental health care is generally considered safe when appropriate essential oils, doses, and delivery methods are used. However, as with any biologically active substance, essential oils carry risks of adverse effects, especially when misused, overused, or applied without proper guidance. Women—particularly during sensitive life stages such as pregnancy, postpartum, or menopause—may be especially vulnerable to certain risks, making safety, contraindications, and regulatory awareness critical to the clinical use of aromatherapy.

6.1. Skin Sensitivity, Phototoxicity, and Allergic Reactions

Topical application of essential oils, such as through massage or baths, is a standard delivery method in aromatherapy. However, this route carries a notable risk of dermatological reactions if essential oils are improperly diluted or used on sensitive skin [60].

6.1.1. Skin Sensitization and Irritation

Essential oils are highly concentrated and must be diluted in carrier oils (e.g., jojoba, sweet almond, or coconut oil) before being applied to the skin [78]. Inappropriate use can result in skin sensitization, an immunologic response that leads to delayed-onset allergic dermatitis. Essential oils such as cinnamon bark, clove, oregano, and thyme are known sensitizers and should be used with extreme caution or avoided in individuals with reactive or atopic skin [113]. Women with a history of eczema, psoriasis, or sensitive skin may be at a higher risk of irritation, especially in thin or hormone-sensitive areas (e.g., during pregnancy) [113].

6.1.2. Phototoxicity

Certain citrus essential oils, particularly bergamot, lemon, lime, and grapefruit, contain furanocoumarins—compounds that can cause phototoxic reactions when exposed to sunlight or UV light. Symptoms include redness, blistering, or hyperpigmentation, often appearing 24–72 h after sun exposure [114]. To avoid this, users should avoid sun exposure for at least 12–18 h after applying phototoxic essential oils topically or choose FCF versions when available.

6.1.3. Allergic Reactions

Although rare, some individuals may experience immediate hypersensitivity reactions such as urticaria, respiratory symptoms, or anaphylaxis.

True allergic responses are more commonly associated with oxidized essential oils, which can form allergenic degradation products over time [115]. To reduce this risk, essential oils should be stored properly (away from light, heat, and oxygen) and used within their recommended shelf life.

6.1.4. Best Practices to Minimize Risk

- Perform a patch test before using any essential oil topically for the first time.

- Use proper dilution: typically 1–2% for healthy adults, and lower (e.g., 0.5–1%) for pregnant women, older adults, or individuals with chronic illness.

- Avoid applying to damaged, broken, or inflamed skin, and exercise caution around mucosal areas.

6.2. General Guidelines

Essential oils should be used with caution during the first trimester, as this is a critical period for fetal development. Always opt for low concentrations (typically 0.5–1%) and use intermittently for short periods. Only use essential oils with an established safety profile in pregnancy under professional guidance.

Essential oils generally considered safe (when properly diluted and used with care):

- Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia)

- Chamomile (Matricaria recutita or Chamaemelum nobile)

- Sweet orange (Citrus sinensis)

- Frankincense (Boswellia carterii)

These are frequently used during labor preparation, in birth environments, and for postpartum stress relief.

Essential oils commonly contraindicated in pregnancy:

- Clary sage (may stimulate uterine contractions—best reserved for labor)

- Rosemary, thyme, cinnamon, oregano, and fennel (can be emmenagogic or hormone-influencing)

- Wintergreen and camphor (contain constituents such as methyl salicylate and camphor that warrant avoidance during pregnancy due to safety concerns at inappropriate doses)

Perinatal Use:

- Postpartum aromatherapy may support emotional recovery, sleep quality, and bonding, particularly through gentle massage or inhalation.

- Infant exposure should be minimized, as newborns have immature detoxification systems and heightened sensitivity to volatile compounds.

Certain essential oils traditionally recognized as emmenagogues, such as S. sclarea (clary sage), Rosa × damascena (rose), Jasminum officinale (jasmine), and Origanum majorana (sweet marjoram), may influence uterine or hormonal activity [116]. Although clinical evidence of adverse reproductive outcomes is limited, their use is not recommended during pregnancy, particularly in the first trimester, due to their potential to stimulate menstrual flow or uterine contractions. When used for other therapeutic purposes, these oils should be applied only under professional supervision and at appropriately low dilutions.

6.3. Regulation and Standardization

The regulation of essential oils and aromatherapy products remains inconsistent across countries, reflecting differences in how these substances are classified and marketed. In many jurisdictions, essential oils are regulated not as therapeutic agents but as cosmetic, fragrance, or wellness products, which limits oversight regarding purity, labeling, and clinical claims [79]. Only a few standardized preparations have undergone pharmaceutical-grade testing and are approved for medical use in specific contexts; most commercial essential oils, however, vary considerably in chemical composition and safety profiles [117].

The European Union classifies essential oils primarily under the Cosmetics Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009, with additional quality control standards defined by the European Pharmacopoeia for select essential oils [118]. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates essential oils based on their intended use: products marketed for therapeutic effects are regulated as drugs, while those promoted for aroma or personal care are considered cosmetics or fragrances [119]. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has established technical standards (ISO 9235, ISO 3515) that define terminology, sourcing, and chemical specifications for essential oils, but compliance remains voluntary [120].

The absence of universal standards poses challenges for research and clinical practice. Variations in essential oil purity, extraction methods, and chemical profiles can lead to inconsistent results and safety concerns. Therefore, researchers and clinicians are encouraged to use pharmacopeia-grade or ISO-certified essential oils, report detailed compositional analyses (e.g., GC–MS profiles), and adhere to good manufacturing and storage practices to ensure reproducibility and patient safety. Strengthening regulatory frameworks and promoting international standardization are essential for integrating aromatherapy into evidence-based women’s mental health care.

7. Challenges and Limitations in the Literature

Despite the growing interest in essential oils as complementary agents in mental health care—especially among women—significant methodological and practical limitations continue to constrain the robustness and generalizability of findings. These challenges underscore the need for more rigorous, standardized research to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and mechanisms of action of aromatherapy interventions.

7.1. Methodological Heterogeneity

One of the most prominent issues in aromatherapy research is the lack of methodological consistency across studies. Variations are evident in study design (e.g., randomized controlled trials vs. quasi-experimental or observational studies), outcome measures (e.g., self-reported scales vs. physiological biomarkers), and intervention protocols (including duration, frequency, and delivery method). These differences hinder comparability and complicate the conduct of meta-analyses and the drawing of definitive conclusions about efficacy.

For example, studies may differ widely in the length of treatment (single exposure vs. 4-week protocols), mode of delivery (inhalation vs. massage), or assessment tools (e.g., STAI, BDI, cortisol levels). The lack of standardized reporting frameworks for aromatherapy research further limits the reproducibility and synthesis of findings across trials.

7.2. Small Sample Sizes and Lack of Blinding

Many studies investigating the psychological effects of essential oils suffer from small sample sizes, often fewer than 50 participants. This limitation reduces statistical power, increases the risk of type II errors, and restricts subgroup analyses that could clarify responses by age, hormonal status, or comorbid conditions.

Additionally, blinding remains a significant challenge in aromatherapy research. Because essential oils have distinctive aromas, it is often difficult to blind participants or practitioners to the intervention, particularly in inhalation studies. Even when placebos (e.g., odorless oils or synthetic fragrances) are used, participants may guess group allocation, introducing expectancy bias. The subjective nature of outcomes (e.g., mood, stress, sleep quality) makes such bias especially problematic in mental health trials.

7.3. Variability in Essential Oils Quality and Chemical Composition

The therapeutic efficacy of an essential oil depends heavily on its chemical profile, which can vary due to factors such as botanical origin, harvest conditions, extraction method, and storage practices. Unfortunately, many studies fail to report critical information such as:

- Botanical species (including chemotypes)

- Extraction method (e.g., steam distillation vs. solvent extraction)

- Purity and presence of possible adulterants

- Batch-specific composition (e.g., GC-MS analysis)

Without this information, it becomes nearly impossible to replicate findings or assess dose–response relationships. Additionally, differences in constituent ratios (e.g., varying linalool content in lavender) may explain discrepancies in observed effects, yet such nuances are rarely addressed.

7.4. Placebo and Control Challenges

A significant limitation in aromatherapy research is the difficulty of achieving double-anonymized conditions. The distinct, recognizable odors of essential oils make it difficult to create an actual placebo effect, as participants may recognize the scent and form expectations about its effects. This introduces the potential for psychological bias, which can influence self-reported outcomes such as mood, anxiety, and stress levels. While some studies have attempted to address this issue by using similar-smelling synthetic essential oils or alternative delivery methods such as massage, these approaches are not without limitations. For example, participants familiar with the typical odor of a specific essential oil may still recognize the intervention, and the tactile effects of massage may confound the results. Future research should prioritize the development of innovative blinding methods to address these challenges and improve the rigor of aromatherapy studies.

As a result, even well-designed studies may face interpretive challenges, in which the observed benefit may not be entirely attributable to the essential oil itself.

7.5. Publication and Reporting Bias

The field of complementary and alternative medicine, including aromatherapy, is particularly susceptible to publication bias. Studies with positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than those with negative or inconclusive results. This may lead to overestimation of effectiveness in systematic reviews and create a distorted view of the evidence base.

Additionally, some studies are published in low-impact or predatory journals, where peer review may be less rigorous. Poor reporting practices—such as omitting details on sample size calculation, randomization, blinding, and statistical methods—further reduce confidence in results.

Although a formal risk-of-bias analysis was not performed due to the narrative nature of this review, potential biases within the included studies—such as lack of blinding, small sample sizes, and heterogeneous methodologies—were acknowledged and taken into account when interpreting the evidence.

Overall, the evidence summarized in this narrative review should be interpreted with caution. Although several randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses support the benefits of specific essential oils, many included studies are preliminary, with small sample sizes, short durations, and heterogeneous designs. This variability limits the strength of the conclusions and underscores the need for more robust and standardized research. The present review, therefore, aims to provide an integrative overview of current findings and identify promising areas for future investigation, rather than to establish causal efficacy.

7.6. Challenges in Conducting Meta-Analyses

The individualized nature of aromatherapy poses significant challenges for conducting meta-analyses or other statistical studies. The variability in individual responses to essential oils, influenced by factors such as personal scent preferences, cultural context, and psychological state, can lead to heterogeneity in study outcomes. This makes it challenging to draw generalized conclusions about the efficacy of specific essential oils or delivery methods.

7.7. Individual Variability and Paradoxical Effects

A significant limitation in aromatherapy research is the variability in individual responses to essential oils. Factors such as genetic differences in olfactory receptor sensitivity, personal scent preferences, and psychological expectations can lead to highly individualized effects, making it challenging to generalize findings across populations. Additionally, certain essential oils, such as citrus oils, have been reported to exhibit paradoxical effects, acting as sedatives in some individuals while stimulating in others. These factors complicate the design and interpretation of aromatherapy studies, particularly in meta-analyses and other statistical analyses. Future research should aim to address these limitations by investigating the mechanisms underlying individual variability and developing personalized aromatherapy protocols.

7.8. Additional Limitations

An additional limitation concerns the variability in chemical composition among essential oils, particularly lavender (L. angustifolia), which may contain differing proportions of linalool, linalyl acetate, camphor, and eucalyptol depending on the cultivar, origin, and extraction method. These compositional differences can modulate the oil’s pharmacological profile—enhancing either sedative or stimulant effects—and may partly explain inconsistencies in clinical outcomes across studies. Since most trials did not report detailed chromatographic analyses or constituent ratios, it was not possible to systematically compare the chemical profiles of the essential oils used. Future studies should therefore include standardized chemical characterization (e.g., GC–MS profiling) to improve reproducibility and interpretability of findings.

8. Future Directions

Aromatherapy holds substantial potential as a supportive modality in women’s mental health, particularly for managing anxiety, depression, and stress-related conditions. To fully realize this potential, future research and clinical practice must evolve beyond preliminary trials and anecdotal evidence. This requires methodological rigor, technological innovation, policy inclusion, and cultural sensitivity. The following areas offer key opportunities for the future of essential oil-based interventions in mental health care:

8.1. Addressing Methodological Limitations

- Standardized Protocols: Future studies should develop and adhere to standardized protocols for essential oil administration, including consistent dosages, delivery methods (e.g., inhalation, massage), and treatment durations. This will improve the comparability of results across studies and facilitate meta-analyses.

- Larger Sample Sizes: Many existing studies are limited by small sample sizes, which reduces statistical power and the ability to generalize findings. Future research should aim to recruit larger, more diverse populations to ensure robust and reliable results.

- Blinding and Placebo Controls: To minimize bias, future studies should employ double-anonymized, placebo-controlled designs. Innovative approaches to blinding, such as using neutral scents or synthetic fragrances as controls, should be explored.

8.2. Exploring Individualized and Culturally Relevant Approaches

- Individual Factors: Research should examine how factors such as age, hormonal status, olfactory preferences, and mental health history influence the efficacy of aromatherapy interventions. Personalized approaches may enhance treatment outcomes.

- Cultural Context: Cross-cultural studies are needed to explore how traditional uses of essential oils align with contemporary clinical applications. This could help develop culturally sensitive aromatherapy protocols that are more widely accepted and effective.

8.3. Investigating Long-Term Effects and Mechanisms of Action

- Long-Term Studies: Most existing studies focus on short-term outcomes. Longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the sustained effects of aromatherapy on mental health and its potential role in preventing anxiety, depression, and stress.

- Mechanistic Research: Further research is needed to elucidate the neurobiological and neurochemical mechanisms underlying the effects of essential oils. Advanced techniques, such as functional neuroimaging and biomarker analysis, could provide valuable insights into how essential oils interact with the brain and endocrine system.

8.4. Integrating Aromatherapy into Clinical Practice

- Clinical Guidelines: Developing evidence-based clinical guidelines for aromatherapy use in mental health care is essential. These guidelines should address safety, efficacy, and best practices for integrating aromatherapy into existing mental health care frameworks.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Future research should evaluate the cost-effectiveness of aromatherapy as a complementary therapy, particularly in resource-limited settings where access to conventional mental health care may be restricted.

8.5. Leveraging Emerging Technologies

- Digital Aromatherapy: Integrating aromatherapy with mobile health (mHealth) platforms and wearable devices offers new opportunities for personalized, scalable interventions. Future research should explore the feasibility and efficacy of these technologies in improving mental health outcomes.

- AI-Driven Personalization: Artificial intelligence could be used to develop personalized aromatherapy protocols based on individual preferences, stress levels, and biometric data.

By addressing these research priorities, the field of aromatherapy can move toward establishing a more robust evidence base, enabling its safe and effective integration into women’s mental health care.

9. Materials and Methods

We conducted a narrative review by searching. To address the research objectives of this narrative review, a comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify relevant scientific articles related to the efficacy and safety of aromatherapy, specifically the use of essential oils, in the management of women’s mental health conditions. The search was conducted in the following databases, accessed on 3 July 2025: PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/), and Web of Science (https://www.webofscience.com/), which were selected for their comprehensive coverage of biomedical, psychological, and complementary and integrative medicine literature.

The search strategy utilized a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), keywords, and Boolean operators to ensure comprehensive retrieval of studies. Key search terms included but were not limited to: “essential oils”, “aromatherapy”, “anxiety”, “depression”, “stress”, “women”, “female”, “postpartum depression”, and “menopausal symptoms”. These terms were selected to encompass the central themes of the review: essential oil use, mental health outcomes, and women-specific populations. Synonyms and related terms were also incorporated to maximize sensitivity, and filters for human studies were applied where available. Rayyan was used as a reference management and screening support tool to assist with study organization and transparency; its use does not imply that this review followed a systematic review methodology.

9.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Studies published in any language

- Studies published in the last 5 years

- Adult women

- Interventional or observational studies evaluating essential oils or aromatherapy for mental health outcomes

- Studies reporting on anxiety, depression, stress, or related mood symptoms

9.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Animal studies

- Studies not reporting on women or without gender stratification

- Non-mental health outcomes (e.g., purely dermatological or antimicrobial effects)

- Reviews, editorials, and conference abstracts without primary data

9.3. Risk of Bias

Although a formal quantitative risk-of-bias tool was not applied due to the narrative nature of this review, a qualitative critical appraisal was conducted across all included studies. Particular attention was given to methodological features such as sample size adequacy, the presence or absence of randomization and blinding, the use of control or placebo groups, and the clarity of intervention protocols. Studies were also examined for consistency in outcome measures and completeness of reporting. Overall, most clinical trials presented moderate methodological quality, with common limitations including small cohorts, short intervention durations, and incomplete blinding due to the sensory nature of aromatherapy. These factors were considered when interpreting the strength and generalizability of the evidence synthesized in this review.

10. Conclusions

Aromatherapy shows potential as a supportive and complementary approach for women’s mental health, particularly in managing mild to moderate anxiety, depression, and stress. Nevertheless, the current body of evidence is constrained by small sample sizes, methodological heterogeneity, and potential bias, limiting the strength and generalizability of the conclusions. While preliminary results are encouraging, aromatherapy should be regarded as an adjunct to conventional care rather than a substitute for established treatments. Further well-designed, adequately powered studies are essential to confirm its efficacy, clarify its mechanisms of action, and ensure safe, standardized clinical application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, supervision, project administration, S.D.G.; validation, investigation, and writing—review and editing, S.D.G., V.E., R.S.M. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings and conclusions are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANS | Autonomic Nervous System |

| EPDS | Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale |

| FCF | Furocoumarin-free |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GAD | Generalized anxiety disorder |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| HRV | Heart Rate Variability |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| PMS | Premenstrual syndrome |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

References

- Lassi, Z.S.; Wade, J.M.; Ameyaw, E.K. Stages and future of women’s health: A call for a life-course approach. Womens Health 2025, 21, 17455057251331721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.N. Depression in peri- and postmenopausal women: Prevalence, pathophysiology and pharmacological management. Drugs Aging 2013, 30, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barat, S.; Ghanbarpour, A.; Mirtabar, S.M.; Kheirkhah, F.; Basirat, Z.; Shirafkan, H.; Hamidia, A.; Khorshidian, F.; Talari, D.H.; Pahlavan, Z.; et al. Psychological distress in pregnancy and postpartum: A cross-sectional study of Babol pregnancy mental health registry. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, S.; Marques, P.; Matos, R.S. Exploring Aromatherapy as a Complementary Approach in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. J. Palliat. Med. 2024, 27, 1247–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, H.; Zheng, W. Aromatherapy in anxiety, depression, and insomnia: A bibliometric study and visualization analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo Gonçalves, S.; Santos, A.L.; Ramos, C.; Valente, F.; Jesus, L.; Pereira Alexandre, J.; Chyczij, F. Mental Health in Europe After COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Adult Primary Health Care Users. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, A.A.; Phang, V.W.X.; Lee, Y.Z.; Kow, A.S.F.; Tham, C.L.; Ho, Y.-C.; Lee, M.T. Chronic Stress-Associated Depressive Disorders: The Impact of HPA Axis Dysregulation and Neuroinflammation on the Hippocampus—A Mini Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowndhararajan, K.; Kim, S. Influence of Fragrances on Human Psychophysiological Activity: With Special Reference to Human Electroencephalographic Response. Sci. Pharm. 2016, 84, 724–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.K.H.; Lau, B.W.M.; Ngai, S.P.C.; Tsang, H.W.H. Therapeutic Effect and Mechanisms of Essential Oils in Mood Disorders: Interaction between the Nervous and Respiratory Systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malnic, B.; Gonzalez-Kristeller, D.C.; Gutiyama, L.M. Odorant Receptors. In The Neurobiology of Olfaction [Internet]; Menini, A., Ed.; Frontiers in Neuroscience; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK55985/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Purves, D.; Augustine, G.J.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Katz, L.C.; LaMantia, A.S.; McNamara, J.O.; Williams, S.M. The Olfactory Epithelium and Olfactory Receptor Neurons. In Neuroscience [Internet], 2nd ed.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2001. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10896/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Šimić, G.; Tkalčić, M.; Vukić, V.; Mulc, D.; Španić, E.; Šagud, M.; Olucha-Bordonau, F.E.; Vukšić, M.; Hof, P.R. Understanding Emotions: Origins and Roles of the Amygdala. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter-Levin, G. The Amygdala, the Hippocampus, and Emotional Modulation of Memory. Neuroscientist 2004, 10, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattayakhom, A.; Wichit, S.; Koomhin, P. The Effects of Essential Oils on the Nervous System: A Scoping Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulivand, P.H.; Ghadiri, M.K.; Gorji, A. Lavender and the Nervous System. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 681304. [Google Scholar]

- Satou, T.; Koutoku, Y.; Touma, T.; Tomiyama, R.; Ishikawa, A.; Odato, K. Effect of Lavender Essential Oil Topical Treatment on the Autonomic Nervous System in Human Subjects Without Olfactory Influence: A Pilot Study. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2024, 19, 1934578X241275321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.A.; Bales, N.J.; Myers, S.A.; Bautista, A.I.; Roueinfar, M.; Hale, T.M.; Handa, R.J. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis: Development, Programming Actions of Hormones, and Maternal-Fetal Interactions. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 601939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, N.Y.; Wu, Y.T.; Park, S.A. Effects of Olfactory Stimulation with Aroma Oils on Psychophysiological Responses of Female Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarraga-Valderrama, L.R. Effects of essential oils on central nervous system: Focus on mental health. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 657–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimbo, D.; Kimura, Y.; Taniguchi, M.; Inoue, M.; Urakami, K. Effect of aromatherapy on patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychogeriatr. Off. J. Jpn. Psychogeriatr. Soc. 2009, 9, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouly, A.M.; Sullivan, R. Memory and Plasticity in the Olfactory System: From Infancy to Adulthood. In The Neurobiology of Olfaction [Internet]; Menini, A., Ed.; Frontiers in Neuroscience; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK55967/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- de Leon, A.S.; Tadi, P. Biochemistry, Gamma Aminobutyric Acid. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551683/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- López, V.; Nielsen, B.; Solas, M.; Ramírez, M.J.; Jäger, A.K. Exploring Pharmacological Mechanisms of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) Essential Oil on Central Nervous System Targets. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diogo Gonçalves, S. Pruritus in Palliative Care: A Narrative Review of Essential Oil-Based Strategies to Alleviate Cutaneous Discomfort. Diseases 2025, 13, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, C.; Silva, F. The Impact of Lavender Essential Oil on the Human Nervous System: A Review. Braz. J. Health Aromather. Essent. Oil 2025, 2, bjhae22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamalan, O.A.; Moore, M.J.; Al Khalili, Y. Physiology, Serotonin. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545168/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).