Abstract

The demand for clean-label functional foods has increased interest in natural polysaccharides with health benefits. Acemannan, an O-acetylated glucomannan from Aloe vera, possesses antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and prebiotic activities, but its performance in fat-based systems is not well understood. This study examined the incorporation of acemannan into dark chocolate at 1% and 5% (w/w) and its effects on physicochemical, rheological, antioxidant, and sensory properties. Particle size distribution remained within acceptable limits, though the 5% sample showed a larger mean size and broader span. Rheological tests confirmed shear-thinning behavior, with the higher concentration increasing viscosity at low shear and reducing it at high shear. Antioxidant activity measured by the DPPH assay showed modest improvement in enriched samples. Consumer tests with 30 panelists indicated a strong preference (89%) for the 1% formulation, which maintained a smooth mouthfeel and balanced sensory characteristics, while the 5% sample displayed more fruity and earthy notes with lower acceptance. GC–MS analysis revealed altered volatile profiles, and FTIR spectroscopy confirmed acemannan stability in the chocolate matrix. These findings demonstrate that acemannan can be incorporated into dark chocolate up to 1% as a multifunctional, structurally stable polysaccharide ingredient without compromising product quality.

1. Introduction

In recent years, consumer interest in functional foods has grown significantly, primarily due to increased awareness of their potential to prevent chronic diseases, support immune health, and modulate gut microbiota [1,2,3]. This trend is closely tied to the demand for clean-label products with minimal synthetic additives, favoring natural bioactive compounds—particularly plant-derived polysaccharides, antioxidants, and prebiotics [4]. These developments have stimulated interest in incorporating multifunctional ingredients into commonly consumed food matrices to enhance nutritional quality and deliver additional health benefits [5].

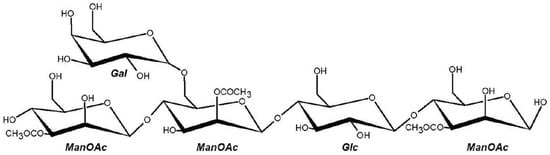

Acemannan, a β-(1→4)-linked O-acetylated polymannan derived from Aloe vera, has emerged as a promising bioactive compound due to its antioxidant, immunostimulatory, and prebiotic properties [1,6]. It belongs to a broader class of plant polysaccharides that offer both physiological benefits and technological functionality in food systems, such as texture modification, stabilization, and bioactive compound delivery [7,8]. Structurally, acemannan consists predominantly of d-mannopyranosyl units, with minor contributions from β-glucose and α-galactose residues. Its degree of O-acetylation, especially at the C-2, C-3, and C-6 positions, enhances solubility, water-binding capacity, and interaction with macromolecules—key factors for its functionality in food matrices [6,9,10]. The chemical structure of acemannan is shown in Figure 1.

Although acemannan has demonstrated promising biomedical effects, its behavior in complex food matrices—particularly with regard to stability, compatibility with lipophilic systems, and sensory impact—remains insufficiently studied or inconsistently reported. Acemannan polysaccharides extracted from Aloe vera have been shown to inhibit phthalate-induced cell viability, metastasis, and stemness in colorectal cancer cells [11]. Acemannan has also been demonstrated to promote tooth socket healing over a 12-month period following extraction [12].

Figure 1.

Representative structural fragment of acemannan, an acetylated β-(1→4)-linked polymannose extracted from Aloe vera gel. The main backbone consists of β-D-mannopyranosyl residues, some of which are acetylated at the C-2, C-3, or C-6 positions (ManOAc). The structure may contain β-D-glucopyranosyl (Glc) units as well as α-D-galactopyranosyl (Gal) side chains linked via (1→6) bonds to the mannan backbone [13].

Chocolate was selected as a model delivery system for acemannan due to its high consumer acceptance and stable fat-based structure. Moreover, it offers a protective matrix for bioactive compounds, potentially enhancing the stability and efficacy of incorporated acemannan [14]. The combination of cocoa’s native polyphenols and acemannan’s biological activities may offer additive or synergistic effects, particularly in the context of oxidative stress and gut health. Technologically, acemannan may influence chocolate’s rheological and textural properties by acting as a natural structuring and moisture-binding agent, making it highly relevant for clean-label innovations. Despite these promising attributes, the integration of acemannan into complex food systems like chocolate remains underexplored, particularly regarding its physicochemical behavior, sensory impact, and consumer perception.

Acemannan has been preliminarily explored in various food applications, including functional beverages, dairy alternatives, confectionery, edible films, and coatings, demonstrating its versatility across product categories [1,5]. Table 1 provides a summary of its representative applications in food systems.

Table 1.

Overview of current and potential food applications of acemannan. Examples of food categories, associated technological roles, and physiological benefits of Aloe vera–derived acemannan in functional food systems, based on recent scientific and industrial reports [1,5,6,8].

Despite encouraging biomedical evidence, there is a lack of comprehensive research investigating how acemannan behaves within real food systems. Specifically, its impact on sensory attributes, product stability, and functional performance in chocolate remains poorly understood.

Although acemannan has been extensively studied in aqueous and gel-like systems, its behavior in lipid-based food matrices remains largely unexplored. In particular, little is known about (i) its structural stability in the absence of free water, (ii) its influence on the rheological behavior of molten systems, and (iii) its effect on the release of volatile compounds and sensory perception [15]. Chocolate represents not only a highly accepted food but also a stable lipid environment that may protect the O-acetylated structures of acemannan from hydrolytic or oxidative degradation, limit oxygen exposure, and modulate aroma release through viscosity and phase partitioning effects. Moreover, possible interactions with cocoa polyphenols could influence astringency and antioxidant capacity [16]. The present study therefore addresses this knowledge gap by systematically evaluating acemannan incorporated into a fat-continuous confectionery matrix (dark chocolate) in terms of its physicochemical, rheological, volatile, and consumer sensory characteristics at two practically relevant concentrations (1 and 5% w/w).

To address this gap, the present study aims to (i) characterize the physicochemical properties of food-grade acemannan (particle size, solubility, viscosity, antioxidant activity, and degree of acetylation); (ii) evaluate its structure via FTIR spectroscopy; (iii) assess its influence on sensory perception and volatile compound profile in chocolate; and (iv) determine its potential as a multifunctional clean-label ingredient in chocolate systems.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically evaluate the integration of purified acemannan into a fat-based confectionery matrix, addressing both physicochemical and sensory dimensions relevant to functional food design. We hypothesize that acemannan, due to its structural and functional properties, can enhance both the technological performance and sensory acceptability of chocolate products.

2. Materials and Methods

Acemannan used in this study was provided by Dazzeon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Taipei, Taiwan). The polysaccharide fractions were isolated from Aloe vera gel using a patented fractionation technology (US 2022/0072080 A1), as described by Shih et al. (2024) [11]. The obtained acemannan fraction (A50) was further characterized by attenuated total reflectance–Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR; Thermo Scientific Nicolet™ iS™ 5, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR; Bruker AVANCE III HD 600 MHz, Bruker BioSpin, Rheinstetten, Germany), and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Agilent 1260-Infinity II Prime LC, Agilent Technologies, Hong Kong, China) to verify its structure and purity.

Chocolate was produced using organic cocoa beans (origin: Colombia) supplied directly by the company’s own partner farmers, ensuring traceability and consistent quality. The beans were roasted, winnowed, and ground in-house. The formulation also included refined white cane sugar (Tereos TTD, Dobrovice, Czech Republic) and organic cocoa butter (BioNebio s.r.o., Prague, Czech Republic). All ingredients were of food-grade quality and used as received. No lecithin or other emulsifiers were added to avoid potential interference with acemannan interactions.

Two dark chocolate formulations were prepared by incorporating 1% and 5% (w/w) acemannan into the base chocolate matrix. The formulations were designated as ACE 1 and ACE 5, respectively.

The base composition (%, w/w) was as follows: cocoa liquor 52.0, cocoa butter 15.0, sucrose and acemannan 33.0 (ACE 1: sucrose 32.0 + acemannan 1.0; ACE 5: sucrose 28.0 + acemannan 5.0). No lecithin or other emulsifiers were used. The target total fat content was approximately 36%, calculated from the fat contribution of cocoa beans and cocoa butter.

Each formulation was prepared in 1.00 kg batches at the professional chocolate factory Steiner & Kovarik (Prague, Czech Republic). Samples were carried out in a controlled environment at 25 °C and 42% relative humidity (RH) using a stone melangeur (Premier, 3 kg bowl, Premier Appliances, Coimbatore, India).

Cocoa beans and cocoa butter were first added to the melangeur and refined for approximately 1 h to achieve a homogeneous base. Subsequently, sucrose and acemannan were gradually added over 30 min, and refining continued for an additional 22.5 h, yielding a total processing time of 24 h. The melangeur was covered with a plastic lid during operation but allowed moderate air exchange to facilitate flavor development and moisture release.

Special care was taken during the addition of acemannan to prevent dusting and adhesion to the melangeur walls. The process was conducted at ambient relative humidity max. 40% RH to minimize moisture uptake.

After refining, the chocolate mass was tempered using the following temperature curve: melting at 47 °C, cooling to 27 °C, and reheating to 31.5 °C. The tempered chocolate was poured onto baking parchment sheets placed on stainless-steel trays and cooled for 2 h in a humidity-controlled cabinet at 10 °C and 40% RH.

The solidified chocolate samples were stored in the dark at 18 ± 1 °C and RH < 50% for 7 days prior to sensory and instrumental evaluation to ensure polymorphic stabilization.

Samples were coded with three-digit random numbers, and the presentation order during the consumer sensory test was balanced and randomized for each assessor.

The characterized material exhibited a purity of 30% acemannan, with an acetyl content of 47% (Lot No. 20230103-2). The sample was used as received for chocolate formulation.

The concentrations of 1% and 5% acemannan extract were selected based on preliminary pilot tests and prior experience with comparable functional ingredients in food applications. Initial trials indicated that concentrations below 1% did not produce any notable changes in the physicochemical parameters or sensory profile of the chocolate, whereas levels above 5% led to undesirable changes in processing consistency and reduced overall acceptability. Therefore, we focused on these two levels as representing the boundary between minimal functional effect and acceptable technological and sensory performance.

The study was designed to compare the effects of two acemannan concentrations (1% and 5%) in an otherwise identical dark chocolate formulation. A control sample without acemannan was not included, as the physicochemical characteristics of the standard formulation had been established in preliminary trials and served as a reference baseline.

2.1. Particle Size Distribution Analysis

Particle size distribution was determined using laser diffraction with a Mastersizer 3000 instrument (Mastersizer 3000, version 3.62; Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, Malvern, UK). Prior to analysis, each chocolate sample (1.0 g) was softened at 40 °C and mechanically stirred using a vortex mixer (IKA Vortex 2, IKA-Werke GmbH, Staufen, Germany) to ensure homogeneity and representative particle sampling. The sample was then dispersed in 50 mL of isopropanol (propan-2-ol; refractive index = 1.390, Penta Chemicals, Prague, Czech Republic), vortexed for 3 min, and immediately analyzed. Isopropanol was selected due to its ability to effectively disperse fat-based matrices without dissolving solid particles.

The measurement was performed using the Mie scattering model with the following parameters: particle refractive index = 1.590, particle absorption index = 0.010. These values were selected based on relevant literature for fat-based particulate systems. A general-purpose analysis model was applied, and the obscuration level was maintained between 10% and 20% to prevent multiple scattering artifacts. Continuous stirring in the dispersion unit was used throughout the measurement to avoid particle sedimentation.

Each sample was analyzed in triplicate to assess measurement repeatability. Variability among replicates was low, indicating consistent particle dispersion and measurement conditions. Apparent particle size distributions were characterized using the volume-weighted mean diameter, the median particle size (D50), and the span, calculated as follows:

Span = (D90 − D10)/D50.

Measurements and data analysis were performed using the Malvern Mastersizer software. Graphical representations of particle size distributions were generated using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

2.2. Rheological Analysis

The rheological properties of the chocolate samples were determined using a rotational rheometer (HAAKE Viscotester iQ, Thermo Scientific, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a concentric cylinder geometry (CC25 DIN/Ti, gap 5.3 mm) and a Peltier temperature control system. The CC25 geometry was selected due to its suitability for viscous, particle-containing systems such as molten chocolate. No phase separation or particle sedimentation was observed during measurement.

Samples were pretreated by melting and homogenization at 45 °C, followed by tempering and stabilization at 40 °C for 24 h to ensure uniformity and minimize air entrapment. Prior to each measurement, samples were equilibrated at the measurement temperature (40 ± 1 °C) for 300 s. Temperature equilibration was verified by monitoring steady torque values before initiating the measurement protocol.

The rheological testing protocol consisted of the following shear rate steps:

- Linear ramp from 0 to 5 s−1 over 60 s;

- Constant shear at 5 s−1 for 240 s;

- Linear ramp from 5 to 60 s−1 over 180 s;

- Constant shear at 60 s−1 for 30 s;

- Linear ramp from 60 to 5 s−1 over 180 s;

- Stepwise decrease from 5 to 0 s−1 in five equal steps over 30 s.

This shear rate protocol was adapted from studies that described the rheological behavior of molten chocolate under conditions relevant to tempering, pumping, and oral processing [17,18]. Shear rates of 5 and 60 s−1 were selected to represent low- and high-shear applications, respectively.

All measurements were conducted in triplicate on freshly prepared samples under identical laboratory conditions. Apparent viscosity values (η) at 5 s−1 and 60 s−1 were calculated directly from the flow curves using RheoWin software (version 4.86, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Karlsruhe, Germany), and reported as mean ± standard deviation.

Statistical significance of differences in apparent viscosity between samples ACE 1 and ACE 5 was evaluated using an unpaired two-tailed t-test (α = 0.05) performed in Microsoft Excel at each shear rate. The analysis was performed using individual replicate values (n = 3 per group).

2.3. Antioxidant Activity

Two chocolate formulations (ACE 1 and ACE 5) were analyzed in triplicate, resulting in six total measurements. Prior to extraction, samples were defatted to remove lipophilic components. Defatting was performed using the Soxhlet extraction method with petroleum ether (Lach-Ner, s.r.o., Neratovice, Czech Republic) as solvent, employing an automated Soxterm 2000 system (C. Gerhardt GmbH & Co. KG, Königswinter, Germany). The procedure followed the five-step method of Soxhlet and Twisselmann, including immersion of the sample in boiling solvent, partial solvent recovery, and lipid collection. After extraction, the beakers were left in a fume hood overnight to allow residual solvent evaporation. The fat content was calculated gravimetrically and used to express antioxidant activity on a fat-free basis.

Antioxidant compounds were extracted from the defatted chocolate by homogenizing 1.0 g of the sample with 50 mL of methanol using an Ultra-Turrax homogenizer (IKA-Werke GmbH, Staufen, Germany) for 5 min. The suspension was subsequently sonicated in an ultrasonic bath (Bandelin electronic GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin, Germany) for 10 min at room temperature and filtered through folded filter paper. All extractions were performed at room temperature and protected from light.

Antioxidant activity was determined using the DPPH (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) radical scavenging assay as described by Brand-Williams et al. [19], with minor modifications in reagent volumes. A 50 µL aliquot of the extract was mixed with 2.0 mL of freshly prepared 0.1 mM DPPH solution in methanol (Lach-Ner, s.r.o., Neratovice, Czech Republic). The mixture was incubated for 15 min in the dark at room temperature. Absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800, Kyoto, Japan). Methanol was used as the blank. A calibration curve was constructed using ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) solutions ranging from 5 to 100 µg/mL (R2 > 0.99), and results were expressed both as mg of ascorbic acid equivalents (AAE) per 100 g of sample and as percentage inhibition of DPPH.

All measurements were performed in triplicate. The expanded measurement uncertainty was estimated at 10%, based on intra-laboratory repeatability, using a coverage factor of k = 2.

2.4. Consumer Sensory Test

A consumer sensory test was conducted to assess the influence of two acemannan concentrations on the sensory perception of dark chocolate [20]. Two sample types were prepared: ACE 1 (1% acemannan) and ACE 5 (5% acemannan), using polysaccharide generously provided by Dazzeon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Taipei, Taiwan). 30 untrained assessors (15 men, 15 women) aged 22–65, all regular dark chocolate consumers with a basic understanding of its flavor profiles, participated in the study. The panelists had no formal sensory training but were briefed on the procedure and key sensory attributes of chocolate before evaluation. Assessments took place in a dedicated room under identical lighting, temperature, and noise conditions; samples were presented in randomized, blind order, each in duplicate. Before each sample, panelists cleansed their palates with still water, unsalted crackers, and coffee beans.

Prior to evaluation, each panelist received a detailed explanation of the procedure and assessed the samples in a dedicated sensory room under controlled conditions, with a maximum of two persons present at a time. Although standard sensory booths were not used, all participants evaluated the samples under identical lighting, temperature, and noise conditions. Calibration samples representing distinct levels of bitterness, sweetness, and fruity notes were provided to harmonize sensory reference points. Each sample was presented monadically in randomized, blind-coded order, and evaluations were performed in duplicate.

Participants rated each sample on a continuous unstructured 100-point hedonic scale (0 = extremely dislike, 100 = extremely like) for overall preference, flavor, texture, and aftertaste. Free-text fields were also provided to capture qualitative impressions. In addition to hedonic scaling, preference tests were conducted for key attributes (overall preference, aroma, and texture), asking participants to indicate their preferred sample in direct pairwise comparisons.

The preference data obtained from the binary forced-choice tests represent the proportion of panelists selecting each sample. Because these outcomes are categorical (binomial) counts rather than continuous measurements, they are expressed as percentages of total responses and are not associated with mean ± SD.

The sensory evaluation was conducted in accordance with ethical principles for research involving human participants. All assessors were informed about the study objectives and voluntarily agreed to participate. No personal or health-related data were collected. Given the non-invasive and low-risk nature of the study, formal ethical approval was not required under institutional guidelines.

2.5. Analysis of Volatile Compounds

Solid-phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (SPME-GC-MS) was employed to extract and identify volatile compounds. The only variable between the two sample groups (ACE 1 and ACE 5) was the concentration of acemannan. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. Volatile compounds were extracted using a DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA), exposed to the headspace of the sample at 60 °C for 30 min. After extraction, the fiber was desorbed in the GC injector at 250 °C for 5 min in split mode (1:20). Analyses were performed using a TRACE GC ULTRA system coupled with an ISQ single quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Separation was achieved on a DB-5MS UI capillary column (60 m × 0.32 mm, 1.0 µm film thickness; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Helium (purity 6.0; Linde Gas, Prague, Czech Republic) was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. The oven temperature program was as follows: 40 °C (held for 5 min), increased at 15 °C/min to 290 °C, and held for 5 min. Mass spectrometry was conducted in electron impact mode at 70 eV with a source temperature of 230 °C. Compounds were identified using the NIST 20 library in Xcalibur software (version 2.1, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) based on mass spectral matching (≥85%) and retention index comparison with literature data or authentic standards.

Retention indices (Kováts indices) were included as part of the identification procedure. Experimental retention indices were compared with published reference values to support and verify compound identification.

Volatile compounds were identified based on mass spectral similarity to reference libraries (NIST 20) and comparison of retention indices with published literature values. Only compounds that met both spectral and retention-index criteria were considered reliably identified.

Retention indices (RIs) were calculated using a homologous series of n-alkanes (C6–C25; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) analyzed under identical chromatographic conditions. Experimental RI values were compared with published literature data to confirm compound identity. Key volatiles relevant for chocolate aroma, including acetic acid, 2,3-butanediol, hexanoic acid, and selected pyrazine derivatives, were additionally verified using analytical standards (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥98% purity). Only compounds meeting both mass-spectral similarity (≥85%) and RI agreement criteria were reported as positively identified, whereas compounds meeting only one criterion were classified as tentative (“t.”). Integrated peak areas were calculated for each identified compound using trapezoidal numerical integration within a retention-time window of ±0.05 min around the target retention time. This approach ensured consistent semiquantitative comparison between samples. Quantification was performed using relative peak-area normalization (% of total ion current).

Quantification was performed using relative peak-area normalization, and results are expressed as the percentage of total ion current (% TIC). Absolute concentrations were not determined, as SPME–GC–MS provides semi-quantitative rather than fully quantitative data. Relative abundance (% TIC) for each replicate was calculated as the peak area of a given compound divided by the sum of peak areas of all identified volatiles in that replicate.

Final results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) based on triplicate measurements for both ACE 1 and ACE 5 samples.

2.6. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded using a Nicolet 6700 FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with KBr and CaF2 beam splitters, a sample holder for KBr pellets and thin films, Smart HATR and NIR modules, and corresponding detectors. KBr pellets were prepared by thoroughly mixing approximately 1 mg of finely ground sample with spectroscopic-grade, anhydrous potassium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and compressing the mixture using a manual hydraulic press (Pike Technologies, Fitchburg, WI, USA) into transparent discs.

Spectra were collected in transmission mode over the wavenumber range of 4000–400 cm−1, at a resolution of 4 cm−1, with 32 scans averaged per spectrum. Background spectra were acquired under the same conditions before each measurement and automatically subtracted.

Two sample types were analyzed: (1) a chocolate matrix enriched with acemannan and (2) pure acemannan powder, used as a reference. Spectral overlays were generated to assess the presence and stability of acemannan-specific functional groups following its incorporation into the chocolate matrix. Spectral acquisition and processing were performed using OMNIC 8.0 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted in a completely randomized design (CRD). For each analytical method (particle size distribution, rheology, antioxidant activity, and sensory evaluation), the two formulations (ACE 1 and ACE 5) were compared based on three independent replicates (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between the samples were evaluated using independent two-sample t-tests at a significance level of α = 0.05. Sensory preference data (binomial choice tests) were analyzed using a binomial test against a 50:50 distribution. Statistical analyses were performed using standard statistical functions. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Particle Size Distribution Analysis

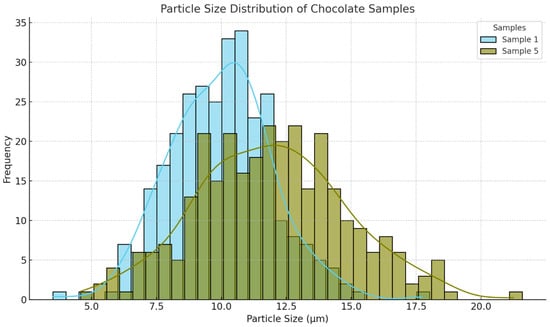

The particle size distribution analysis revealed statistically significant differences between samples ACE 1 and ACE 5. Sample ACE 1 exhibited a narrower distribution, with a mean particle size of 9.99 ± 1.97 µm, while ACE 5 showed a broader distribution with a higher mean particle size of 11.94 ± 2.88 µm. An independent t-test confirmed the statistical significance of this difference (t = −9.65, p < 0.001). Although the mean values differed significantly, both remained within the range generally considered acceptable for ensuring a smooth texture in dark chocolate. The full distribution profiles are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Particle size distribution of chocolate samples ACE 1 (Sample 1) and ACE 5 (Sample 5). Volume-based particle size distributions were measured by laser diffraction. Sample ACE 1 displayed a narrower distribution with a lower mean particle size, whereas ACE 5 exhibited a broader distribution and larger mean particle size, indicating distinct dispersion characteristics.

3.2. Rheological Properties of Chocolate Samples

The rheological profiles of chocolate samples ACE 1 and ACE 5 were evaluated based on apparent viscosity values obtained at defined shear rates. Both formulations demonstrated characteristic non-Newtonian, shear-thinning behavior, with decreasing viscosity as shear rate increased.

To allow quantitative comparison under processing-relevant conditions, apparent viscosity values were extracted at shear rates of 5 s−1 and 60 s−1, corresponding to low- and high-shear regimes, respectively. These values were calculated as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from triplicate measurements in a ±5% range around the target shear rates. Results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Apparent viscosity values (η, Pa·s) of chocolate samples measured at shear rates of 5 s−1 and 60 s−1 (mean ± standard deviation (SD), n = 3).

At 5 s−1, sample ACE 5 exhibited slightly higher viscosity values (7.39–7.57 Pa·s) compared to ACE 1 (7.22–7.68 Pa·s); however, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.667). In contrast, at 60 s−1, ACE 5 showed significantly lower viscosity (2.65–2.67 Pa·s) than ACE 1 (2.91–3.07 Pa·s), with the difference confirmed by t-test (p = 0.026).

These results suggest that acemannan addition increases flow resistance under low shear but enhances shear-thinning behavior at higher shear rates, likely due to microstructural rearrangements in the chocolate matrix.

Apparent viscosity exceeded 700 Pa·s at very low shear rates (<0.5 s−1), as seen in the flow curves, reflecting the strong resistance to initial deformation. However, these values were not included in the summary data due to limited industrial relevance. Instead, shear rates of 5 and 60 s−1 were selected to represent realistic flow conditions. The apparent discrepancy between maximum viscosity values in the flow curves and the summary data in Table 2 is thus a result of the material’s shear-thinning nature and the focus on specific shear rates for standardized comparison.

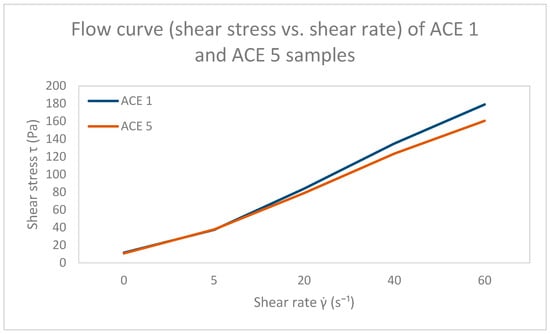

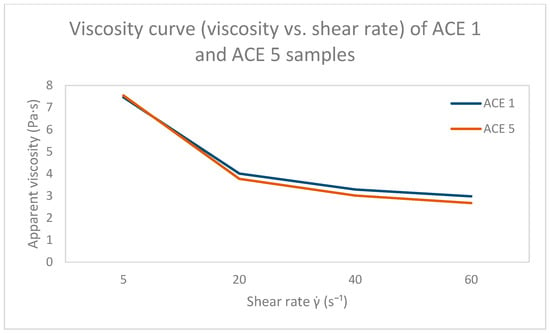

The flow behavior of samples ACE 1 and ACE 5 is shown in two separate rheograms. Figure 3 presents the shear stress as a function of shear rate (flow curve), while Figure 4 shows the corresponding apparent viscosity curves. Both samples are included in each graph to enable direct visual comparison.

Figure 3.

Flow curve (shear stress as a function of shear rate) of dark chocolate samples enriched with 1% (ACE 1) and 5% acemannan (ACE 5) at 40 °C. The measurements show the characteristic increase in shear stress with rising shear rate, enabling direct comparison of flow behavior between the two formulations.

Figure 4.

Apparent viscosity (η) as a function of shear rate for dark chocolate samples enriched with 1% (ACE 1) and 5% acemannan (ACE 5) at 40 °C. The curves show the characteristic shear-thinning behavior of molten chocolate, with decreasing viscosity at higher shear rates, allowing for direct comparison of the flow resistance between the two formulations under processing-relevant conditions.

While ACE 5 generally exhibited higher apparent viscosity than ACE 1 at low shear rates, this trend reversed at high shear (60 s−1), where ACE 5 showed slightly lower viscosity. This behavior reflects the complex shear-thinning response and potential microstructural rearrangements influenced by acemannan concentration.

Quantitative data on viscosity at these two shear rates are summarized in Table 2. At 5 s−1, ACE 1 exhibited a mean apparent viscosity of 7.40 ± 0.25 Pa·s, while ACE 5 reached 7.47 ± 0.09 Pa·s; this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.667). At 60 s−1, the trend was reversed, with ACE 5 showing significantly lower viscosity (2.66 ± 0.01 Pa·s) compared to ACE 1 (2.97 ± 0.09 Pa·s; p = 0.026). These results indicate that acemannan content modulates the rheological behavior of chocolate in a shear-dependent manner, increasing resistance to flow at low shear but promoting enhanced shear-thinning under higher shear conditions.

3.3. Antioxidant Activity Results

Table 3 summarizes the antioxidant activity of both chocolate samples. ACE 5 exhibited slightly higher antioxidant activity (796 ± 43.3 mg AAE/100 g) and DPPH inhibition (65.5 ± 3.6%) compared to ACE 1 (772 ± 40.6 mg AAE/100 g and 63.4 ± 3.4%, respectively). Despite this increase, the values remained within overlapping uncertainty ranges. The difference between ACE 1 and ACE 5 was not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Table 3.

Antioxidant activity and DPPH inhibition of chocolate samples (mean ± SD, n = 3).

3.4. Consumer Sensory Evaluation Results

3.4.1. Consumer Preference Evaluation

The overall preference test revealed a strong consumer preference for the chocolate sample containing a lower concentration of acemannan (ACE 1), with 89% of the 30 panelists favoring ACE 1 over ACE 5 (11%) (Table 4). This result suggests a potential trade-off between increasing functional ingredient content and maintaining sensory acceptability, as higher acemannan levels may compromise certain sensory attributes despite offering potential health benefits.

Table 4.

Preference values represent the proportion of respondents selecting each sample in a binary choice test (n = 30). As these are categorical data based on counts, mean ± SD is not applicable.

Among the preference-tested attributes, ACE 1 was rated more favorably in sweetness, mouthfeel, smoothness, and aroma, with the exception of fruitiness, where ACE 5 received slightly higher ratings. Specifically, ACE 1 was preferred by 57% of panelists for smoothness and by 61% for aroma, compared to 43% and 39% for ACE 5, respectively (Table 4).

3.4.2. Hedonic Evaluation

Quantitative hedonic evaluation using a 0–100 line scale revealed nuanced differences in key sensory attributes such as fruitiness, sweetness, and mouthfeel satisfaction (Table 5). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from 30 consumer ratings per sample. Notably, ACE 5 exhibited slightly elevated scores in fruitiness satisfaction (72%) compared to ACE 1 (68%), aligning with qualitative observations of more pronounced fruity, cherry-like aromatic notes at higher acemannan concentration. A similar effect has been described in the literature, where polysaccharides modulate fruity and acidic perceptions [21]. However, the differences in hedonic scores between ACE 1 and ACE 5 were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Table 5.

Hedonic scores (mean ± SD) for key sensory attributes evaluated by 30 consumers for chocolate samples ACE 1 and ACE 5 (0–100 scale).

Conversely, ACE 1 scored higher in sweetness (89%) and mouthfeel satisfaction (93%) compared to ACE 5 (sweetness: 86%; mouthfeel: 91%), suggesting that higher acemannan content may modestly suppress perceived sweetness and alter mouthfeel, which may be explained by previously described mechanisms such as saliva–polysaccharide interactions or flavor release dynamics.

3.4.3. Consumer Sensory Evaluation

Detailed qualitative assessment further illuminated sensory differences between the two samples (Table 6). Both ACE 1 and ACE 5 exhibited rich aroma profiles characterized by berry, coffee, and tobacco leaf notes, harmonized with the intrinsic bitterness of dark chocolate balanced by coconut sugar. Specifically:

Table 6.

Summary of consumer sensory evaluation results.

- ACE 1 demonstrated an initial clean bitterness with pronounced red-fruit undertones and stronger astringency in the aftertaste.

- ACE 5 initially presented earthy nuances, subsequently evolving into intense, clearly identifiable fruity notes reminiscent of cherry. Astringency was less prominent, possibly masked by the dominant fruity character and the structural interactions influenced by higher acemannan concentration.

These observations suggest that the chocolate sample containing 5% acemannan exhibits enhanced perception of fruity flavors, particularly cherry-like notes. While the exact mechanism was not investigated in this study, such sensory effects may be related to previously described interactions between polysaccharides and aroma compound release or with salivary proteins, which are known to modulate flavor perception [21].

As the sensory panel consisted of untrained consumers, the results represent consumer preference and hedonic perception, not a descriptive sensory profile.

3.4.4. Statistical Analysis (t-Test)

To assess whether the observed differences between ACE 1 and ACE 5 were statistically meaningful, two types of analyses were conducted:

- (1)

- A two-sample independent t-test was used to compare mean hedonic scores for fruitiness, sweetness, and mouthfeel satisfaction (Table 5). No statistically significant differences were found at the α = 0.05 level; however, a trend was observed for mouthfeel (t = –1.83, p = 0.090), suggesting a possible difference with a larger sample.

- (2)

- For preference data (Table 4), binomial tests were applied to assess whether the distribution of consumer choices differed significantly from chance (50:50). A statistically significant preference for ACE 1 was confirmed for overall preference (p < 0.01), while differences in other attributes were not statistically significant.

3.5. Volatile Compound Profiles (GC–MS Results)

Quantitative GC-MS analysis revealed notable differences in the volatile compound profiles between the samples containing 1% (ACE 1) and 5% (ACE 5) acemannan. A detailed evaluation of the chromatographic data demonstrated the following key findings:

- Volatile compounds eluting between 3.0 and 10.0 min exhibited substantial variations in both qualitative presence and quantitative intensity across the two samples.

- The ACE 5 sample consistently showed increased peak areas for major volatiles compared to ACE 1, indicating either a higher concentration or enhanced release of certain aromatic molecules.

- Compounds such as ethanol, acetic acid, and isovaleraldehyde were among those most prominently elevated in the ACE 5 sample.

- The increased intensity in ACE 5 suggests that higher acemannan content may influence the volatility and partitioning behavior of aroma-active compounds within the matrix, likely due to changes in viscosity and microstructural interactions.

As SPME–GC–MS provides semi-quantitative rather than fully quantitative data, no statistical comparison was applied, and results were interpreted descriptively.

A comparative chromatographic profile (Table 7) visually illustrates the differences between ACE 1 and ACE 5, highlighting the increased intensity of numerous compounds in the ACE 5 sample.

Table 7.

Retention times and corresponding compounds identified in the analyzed sample. The table presents the retention times tR of individual peaks obtained by chromatographic analysis and their respective compound assignments based on comparison with authentic standards and spectral data. Identified compounds were eluted in order of increasing polarity and are listed according to their appearance in the chromatogram.

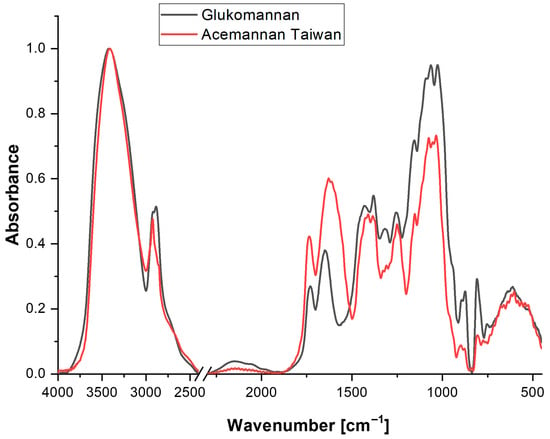

3.6. FTIR Spectral Analysis Results

The FTIR spectra obtained for the chocolate-acemannan matrix and pure acemannan powder exhibited highly comparable profiles. Major characteristic bands attributed to acemannan were observed in both samples, including the following:

- The C=O stretching vibration of acetyl groups at approximately 1740 cm−1.

- The C–O–C stretching and C–O–H bending vibrations between 1000 and 1200 cm−1.

- A broad O–H stretching vibration around 3400 cm−1.

No significant spectral shifts, loss of characteristic peaks, or changes in peak intensities were detected in the chocolate-acemannan matrix when compared to pure acemannan powder.

These results indicate that the incorporation of acemannan into the chocolate matrix did not induce any detectable chemical degradation or interactions altering its key structural features. FTIR analysis is qualitative in nature; therefore, spectral features were evaluated descriptively rather than statistically.

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Particle Size Distribution on Chocolate Quality

Particle size distribution (PSD) plays a critical role in determining the rheological and sensory properties of chocolate, influencing viscosity, texture, mouthfeel, and overall product quality. The statistical analysis confirmed a significant difference in mean particle size between ACE 1 and ACE 5 (p < 0.001). Smaller particle sizes are generally associated with lower viscosity and smoother textures, while larger particles can lead to increased viscosity and a coarser mouthfeel. The broader PSD observed in ACE 5, as supported by the statistically higher mean particle size, may be attributable to the presence of acemannan, which could interfere with particle dispersion or reduce milling efficiency due to its hygroscopicity or structural characteristics.

Previous studies have shown that chocolates with a higher proportion of fine particles demonstrate improved flow properties and enhanced sensory appeal [22]. In contrast, higher levels of coarse particles tend to increase viscosity and negatively impact consumer perception. D90 particle size near 30 µm represents an optimal balance for texture and flow in dark chocolate formulations [17]. Additionally, it is well established that particles above 35 µm can contribute to gritty sensations, while smaller particles enhance creaminess and mouthfeel.

Controlling PSD not only affects sensory perception but also enables fat reduction without sacrificing quality. Tightly packed fine particles contribute to desirable rheological properties even at lower fat levels, supporting the development of healthier chocolate formulations [23].

Despite the statistically significant difference in PSD, hedonic ratings showed no statistically significant differences in mouthfeel between samples (p > 0.05), indicating that both remained within the acceptable threshold for high-quality dark chocolate. Overall, the observed variations in PSD may have technological relevance but did not compromise the sensory performance of the final product, as supported by the non-significant differences in hedonic mouthfeel scores (p > 0.05).

4.2. Impact of Acemannan Concentration on Rheological Behavior

The results clearly demonstrate that acemannan concentration affects the rheological properties of the chocolate matrix. This effect was supported by the statistical analysis, which confirmed a significant difference in apparent viscosity between ACE 1 and ACE 5 at the high shear rate (60 s−1; p = 0.026), while no significant difference was observed at low shear (5 s−1; p = 0.667). Specifically, the higher acemannan content in sample ACE 5 (5%) led to a slight, though statistically non-significant, increase in apparent viscosity under low shear conditions compared to ACE 1 (p = 0.667). This trend is in agreement with previous reports showing that plant-derived polysaccharides can increase viscosity and resistance to flow due to their ability to form entangled networks and reduce molecular mobility [1,10].

The increase in apparent viscosity observed in the acemannan-enriched samples can be attributed not only to the higher total solids content but also to the hydrocolloid nature of acemannan, which interacts with both dispersed and continuous phases in the chocolate matrix. The polysaccharide chains can enhance interparticle friction and partially restrict the mobility of fat molecules, leading to increased resistance to shear. Moreover, the partial replacement of crystalline sucrose by amorphous polysaccharide reduces the proportion of the freely moving lipid phase, effectively increasing the solid volume fraction and contributing to higher yield stress and consistency. Such rheological behavior is commonly reported in fat-based systems containing polysaccharides with water-binding and network-forming capabilities [24].

Interestingly, at a high shear rate (60 s−1), ACE 5 exhibited significantly lower apparent viscosity than ACE 1 (p = 0.026), indicating enhanced shear-thinning behavior in the acemannan-enriched formulation. This finding supports the idea that acemannan alters not only static resistance to flow but also dynamic flow properties under processing conditions.

The observed shear-thinning behavior aligns with the known rheological characteristics of molten chocolate, where increasing shear rate reduces internal friction through molecular alignment and partial disentanglement. This behavior is advantageous in processing operations such as tempering, pumping, and enrobing, which require high flowability at elevated shear while maintaining structure and coating performance at rest or low shear [25,26,27].

The higher apparent viscosity and altered flow response observed in ACE 5 are consistent with the presence of stronger intermolecular interactions and structural entrapment caused by acemannan enrichment. These observations are in accordance with studies on polysaccharide-enriched food systems, where hydrocolloids increase yield stress and modify viscoelastic behavior [18,28].

From an industrial perspective, the increased viscosity resulting from acemannan incorporation may necessitate modifications in chocolate formulation or process parameters. Possible strategies include adjusting emulsifier content, optimizing the fat phase, or implementing precise temperature control to counterbalance the thickening effects and ensure acceptable flow behavior and sensory properties [25].

These findings highlight the importance of integrating rheological profiling with sensory and structural analysis in future investigations. A multidisciplinary approach will be essential for developing optimized, functional chocolate products with targeted performance and consumer acceptance.

Acemannan, as a hydrocolloid polysaccharide, can influence the texture of chocolate primarily through its impact on rheology and particle interactions within the fat-continuous matrix. Its hydrophilic backbone has a high capacity for hydrogen bonding, which promotes the formation of a weak polysaccharide network and increases low-shear viscosity. This effect can enhance the perception of body and smoothness while maintaining flowability under shear during processing. The shear-thinning behavior observed in acemannan-enriched samples suggests that the polysaccharide interacts with both solid cocoa particles and the lipid phase, forming transient structures that contribute to a slightly thicker and creamier mouthfeel. Such hydrocolloid-induced modifications of texture have also been reported in other confectionery and emulsion systems [29].

Overall, the rheological differences observed between ACE 1 and ACE 5 were statistically significant only at high shear, indicating that acemannan affects the dynamic flow properties more strongly than low-shear behavior.

4.3. Impact of Acemannan Incorporation on the Antioxidant Activity of Chocolate

The antioxidant activity observed in both chocolate samples is consistent with previously reported values for high-quality dark chocolates rich in polyphenols, particularly catechins and procyanidins [14]. Sample 5, enriched with a functional polysaccharide ingredient—acemannan—demonstrated a modest increase in both antioxidant capacity and DPPH inhibition compared to Sample 1. However, these differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Although the observed differences in antioxidant values were small, statistically non-significant (p > 0.05), and within the range of measurement uncertainty, the trend is consistent with the hypothesis that acemannan enrichment may contribute positively to the antioxidant profile of chocolate. Both chocolate samples were produced from identical ingredient batches and processed under strictly controlled and identical conditions, minimizing variability unrelated to the presence of acemannan. Therefore, the observed differences can reasonably be attributed to the functional ingredient, although confirmation through additional controls and isolated testing of acemannan is recommended for future studies. This interpretation is further supported by previous research demonstrating the antioxidant potential of acemannan through both direct radical scavenging and modulation of antioxidant defense pathways [1,10].

It should be noted, however, that the stability and functional efficacy of acemannan can be significantly influenced by processing conditions such as temperature and pH. Drying techniques used during the production of acemannan-rich extracts, including spray-drying and refractance window drying, are known to reduce the degree of acetylation and consequently the bioactivity of the polymer [10]. Therefore, maintaining acemannan integrity during chocolate processing is essential to preserve its health-promoting properties.

In conclusion, this pilot study indicates that the addition of acemannan may offer slight but measurable improvements in the antioxidant properties of chocolate. Further research involving a broader sample set, detailed polyphenol profiling, and in vitro digestion models is warranted to confirm these findings and to elucidate the mechanisms involved.

Overall, the antioxidant results indicate that acemannan addition did not lead to statistically significant improvements in antioxidant capacity under the conditions tested.

The antioxidant capacity of the chocolate samples was assessed using the DPPH radical-scavenging assay, which provides a rapid and widely accepted estimation of electron-donating ability. However, it is recognized that antioxidant activity cannot be fully described by a single method, as different assays reflect distinct reaction mechanisms (electron transfer vs. hydrogen atom transfer). The exclusive use of DPPH in this study therefore represents a limitation, providing only an indicative comparison between formulations. Future work should include complementary methods such as ABTS, FRAP, or ORAC to obtain a more comprehensive evaluation of antioxidant capacity.

4.4. Consumer Preferences

The results of the hedonic ratings suggest that chocolate samples containing different concentrations of acemannan exhibit distinct sensory profiles that appear to influence consumer acceptance and preference. However, the differences in hedonic scores were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The sample containing 1% acemannan (ACE 1) was more frequently preferred by panelists, which was statistically confirmed only for overall preference (p < 0.01), while other preference attributes showed no significant differences (p > 0.05). As preference tests yield categorical (binomial) outcomes rather than continuous scores, these results are appropriately reported as proportions of respondents, and measures such as mean ± SD are not applicable to this type of data. These findings are consistent with previous literature suggesting that lower concentrations of polysaccharides in food matrices typically enhance sweetness perception and positively influence textural attributes [21,30].

In contrast, the chocolate sample containing 5% acemannan (ACE 5) was characterized by increased fruitiness, with sensory descriptors highlighting earthy notes evolving into intense fruity, particularly cherry-like aromas. The increased fruitiness observed in ACE 5 aligns well with previously reported effects of polysaccharides on the modification of flavor perception, likely due to their capacity to modulate aroma compound release or interactions with saliva proteins [8,21,30]. Moreover, ACE 5 exhibited lower astringency perception, which could be explained by acemannan’s ability to interact with tannins and other polyphenolic compounds, potentially reducing perceived astringency and enhancing overall fruity character [10].

The difference in perceived astringency between the samples was not statistically significant (p > 0.05), but qualitative feedback suggested a perceptible trend. The observed reduction in perceived astringency in the 5% acemannan sample may be attributed to potential non-covalent interactions between acemannan and cocoa polyphenols. Hydroxyl groups of acemannan chains can form hydrogen bonds with phenolic hydroxyls, while the hydrophobic regions of the polysaccharide may promote weak hydrophobic interactions, leading to the partial sequestration of polyphenols. Such interactions could reduce the availability of polyphenols to bind with salivary proteins, thereby decreasing oral astringency. Similar polysaccharide–polyphenol complexes have been reported to modulate sensory perception and antioxidant activity in other food systems [31].

Although texture and aroma preferences were moderately distributed between the two samples, a slight preference was still observed for ACE 1. This preference distribution suggests a consumer tendency towards sensory profiles characterized by a smoother texture and balanced sweetness, indicating that optimal levels of functional ingredients like acemannan must be carefully considered to balance the trade-offs between desired health functionalities and sensory quality [4].

Qualitative feedback further elucidated the distinct sensory profiles of the two chocolate samples. ACE 1 was described as exhibiting a classic cocoa profile with pronounced astringency, whereas ACE 5 was notably earthy and intensely fruity. This sensory differentiation emphasizes the complex interplay between functional ingredients and the sensory attributes of chocolate matrices, highlighting the need for careful formulation strategies when incorporating novel bioactive compounds [6,14].

Overall, these findings indicate that moderate acemannan addition (1%) resulted in the highest consumer acceptance, although most hedonic differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). This outcome suggests the importance of maintaining an optimal balance between the level of functional ingredient and overall sensory acceptability in functional chocolate formulation. Considering that the sensory data were obtained from untrained consumers, these results should be interpreted as indicators of consumer preference rather than analytical sensory profiling. Future studies should therefore employ larger consumer panels and complementary instrumental analyses—such as detailed volatile compound profiling and rheological evaluation—to confirm these sensory trends and further optimize acemannan-enriched chocolate formulations.

4.5. Quantitative Comparison and Influence of Acemannan on Volatile Compound Profiles in Chocolate

The higher concentration of acemannan (5%) in ACE 5 compared to ACE 1 (1%) had a marked influence on the volatile profile of the chocolate. Volatile compound data were evaluated semi-quantitatively using relative peak-area normalization (% TIC), expressed as mean ± SD from triplicate measurements. Although inferential statistics were not applied, the semi-quantitative data allow a clear comparison of relative abundances between ACE 1 and ACE 5. Previous studies have demonstrated that polysaccharides, including acemannan, significantly affect the viscosity and rheological properties of chocolate matrices, which can influence the volatility and release dynamics of aroma compounds [10]. An increased viscosity may lead to physical entrapment of volatiles, thereby reducing their release during olfactory evaluation [5]. Moreover, higher levels of bioactive polysaccharides such as acemannan are associated with enhanced antioxidant activity [14], which could contribute to improved stability of volatile compounds and modulate their interactions within the chocolate matrix. Acetic acid, ethanol, and other low-molecular-weight volatiles detected in the samples are known to play important roles in defining key sensory attributes such as acidity and fruitiness. The observed shifts in the volatile profiles suggest that ACE 5 samples may present enhanced fruity and acidic sensory characteristics.

The stronger perception of fruity volatile compounds in the 5% acemannan sample may be related to changes in viscosity and phase partitioning within the chocolate matrix. A higher concentration of acemannan likely increases the system’s viscosity and alters the distribution of volatile molecules between the lipid phase and the headspace. In addition, weak non-covalent interactions between polysaccharide chains and aroma-active compounds (e.g., esters and aldehydes) could modulate their release kinetics, resulting in a prolonged or more intense fruity impression. Similar polysaccharide–aroma interactions have been reported in other food matrices, supporting this observation [15].

The key aroma-active groups detected in both chocolate samples aligned with typical volatile profiles previously reported for dark chocolate. Acids represented a dominant group, with acetic acid showing the highest abundance in both samples, accompanied by formic, isobutyric, isovaleric, and 2-methylbutanoic acids, all of which contribute to acidic, fermented, and slightly cheesy–fruity notes characteristic of cocoa fermentation. Pyrazines such as trimethylpyrazine and tetramethylpyrazine were clearly present in both ACE 1 and ACE 5 and represent essential contributors to roasted, cocoa-like aroma. Alcohols, including ethanol and 2,3-butanediol, were more pronounced in ACE 5 and may reflect differences in matrix interactions affecting volatility. Aldehydes and ketone-related compounds such as acetoin and acetone were also identified, contributing sweet, creamy, and mild fruity nuances. Terpenes such as linalool and D-limonene contributed floral and citrus-like notes. Together, these groups represent the most sensory-relevant volatiles in cocoa-based matrices and form the basis for interpreting differences between the two acemannan concentrations.

ACE 1 showed a markedly higher relative abundance of acetic acid, as reflected by the higher mean % TIC values observed in Table 7, which is consistent with a more pronounced acidic and fermentation-related character. In contrast, ACE 5 exhibited substantially elevated relative peak levels of ethanol and 2,3-butanediol, based on chromatographic intensity (non-statistical comparison), compounds typically associated with sweet, mellow, and slightly fruity notes. Furthermore, the 5% acemannan sample displayed a clearer pyranone signal, based on relative chromatographic intensity (non-statistical comparison), indicative of caramel-like or fruity–caramel attributes, while the distribution of pyrazines remained comparable between the samples, contributing characteristic roasted cocoa notes in both cases. These quantitative and qualitative shifts suggest that higher acemannan concentrations may selectively modulate the volatility and release of specific aroma-active compounds, leading to a sweeter, rounder, and more fruity, aromatic impression in ACE 5, whereas ACE 1 retains a sharper, more acidic profile dominated by acetic acid.

These observations reflect semiquantitative differences supported by the % TIC values reported in Table 7.

4.6. Structural Stability of Acemannan in Chocolate Matrix

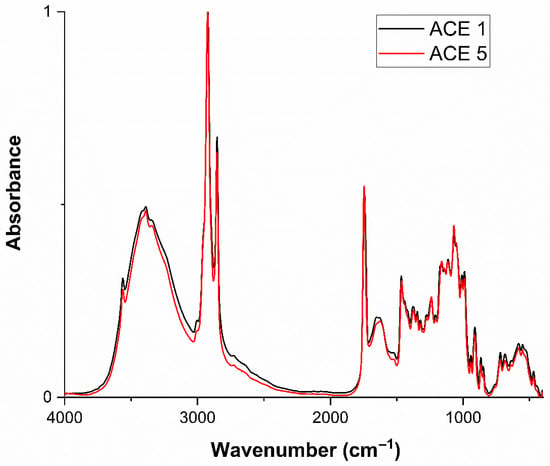

FTIR spectra obtained for the chocolate samples (ACE 1 and ACE 5) were directly compared with the spectrum of isolated acemannan (Figure 5). The FTIR data were evaluated qualitatively, as FTIR spectroscopy is not suitable for statistical comparison of peak intensities in this context. All major characteristic absorption bands were preserved, with no observable spectral shifts or intensity loss, indicating structural stability of acemannan after incorporation into the chocolate matrix. Figure 6 further compares ACE 1 and ACE 5 samples, showing consistent profiles across concentrations. The retention of characteristic functional groups further suggests that acemannan maintains its molecular integrity during chocolate processing. These findings support the feasibility of incorporating acemannan as a functional ingredient in chocolate-based products, facilitating the development of novel food formulations with potential health benefits. These observations are based on qualitative spectral comparison, which is appropriate for FTIR analysis.

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of isolated Aloe vera acemannan and glucomannan standard. The acemannan spectrum (red line) shows characteristic peaks at ~1740 cm−1 (C=O stretching), ~1035 cm−1 (C–O–C stretching), and ~3300 cm−1 (O–H stretching), confirming its acetylated polymannan structure.

Figure 6.

Overlay of FTIR spectra comparing ACE1 and ACE5 in the spectral range of 4000–400 cm−1.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically evaluated the incorporation of acemannan, an Aloe vera–derived bioactive polysaccharide, into dark chocolate at two inclusion levels (1% and 5%) and demonstrated that acemannan can serve as a clean-label functional ingredient without undermining core product quality. At the 1% enrichment level, particle size distribution, rheological behavior, antioxidant capacity, and sensory acceptance remained statistically indistinguishable from the control, indicating that low-level acemannan addition does not alter chocolate microstructure or consumer perception. The 5% formulation, while still processable in a professional melangeur and technologically acceptable, exhibited a modest but significant increase in mean particle size (p < 0.001) and altered shear-thinning profiles (higher viscosity at low shear, reduced viscosity at high shear), suggesting that higher acemannan proportions affect dispersion and flow behavior. GC–MS analysis revealed that volatile compound release (notably esters and aldehydes associated with fruity and earthy notes) was enhanced in the 5% sample, correlating with panelists’ sensory reports of more pronounced fruity and earthy attributes. FTIR spectroscopy confirmed that acemannan’s characteristic functional groups remained intact post-processing, evidencing no chemical degradation or undesirable interactions with cocoa constituents. Antioxidant activity measured by DPPH radical scavenging showed a dose-dependent increase in ascorbic acid equivalents (AAE), further supporting acemannan’s contribution to functional value.

Overall, these findings establish that up to 1% acemannan enrichment is imperceptible to consumers while delivering added antioxidant benefit, whereas 5% enrichment yields detectable sensory and rheological modifications that may be leveraged for targeted flavor profiles. Future work should assess the shelf-life stability of acemannan-enriched chocolates, conduct broader consumer acceptance testing across diverse demographics, and evaluate in vivo bioaccessibility and glycemic modulation effects of acemannan when delivered via a chocolate matrix. Such efforts will clarify long-term viability and health impacts, thereby advancing the development of next-generation functional chocolate products.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P.; methodology, M.S.; validation, V.K. and J.Č.; formal analysis, V.K.; investigation, V.K.; resources, E.P.; data curation, V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, V.K. and N.P.; writing—review and editing, V.K., N.P., E.P., M.S. and J.Č.; visualization, V.K.; supervision, J.Č.; project administration, V.K.; funding acquisition, E.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because consumer tests with adult volunteers did not involve medical intervention, collection of sensitive personal data, or any risk to participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Raw data are not publicly archived, as they are unprocessed, but the processed and summarized data are included in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dazzeon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Taiwan) for providing the raw material used in this study. Analytical measurements were performed at UCT Prague as part of contractual analytical services.

Conflicts of Interest

Ekambaranellore Prakash was previously associated with Dazzeon Biotech Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received acemannan polysaccharide (the raw material) as support from Dazzeon Biotech Co. The company was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAE | Ascorbic acid equivalents |

| ACE 1, ACE 5 | Chocolate samples containing 1% and 5% acemannan, respectively |

| D10 | Particle diameter below which 10% of the sample volume exists |

| D50 | Median particle diameter (50% of particles are smaller, 50% larger) |

| D90 | Particle diameter below which 90% of the sample volume exists |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| GC–MS | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| HATR | Horizontal attenuated total reflectance |

| ISQ | Single quadrupole mass spectrometer |

| NIR | Near-infrared spectroscopy |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| PSD | Particle size distribution |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| RT | Retention time |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SPME | Solid-phase microextraction |

| UV-Vis | Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy |

References

- Bai, Y.; Niu, Y.; Qin, S.; Ma, G. A New Biomaterial Derived from Aloe vera—Acemannan from Basic Studies to Clinical Application. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenssen, K.G.M.; Bast, A.; De Boer, A. Clarifying the Health Claim Assessment Procedure of EFSA Will Benefit Functional Food Innovation. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 47, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hua, H.; Zhu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yao, W.; Qian, H. Aloe Polysaccharides Ameliorate Acute Colitis in Mice via Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling Pathway and Short-Chain Fatty Acids Metabolism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 185, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigliardi, B.; Galati, F. Innovation Trends in the Food Industry: The Case of Functional Foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 31, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada, M.P.; Salinas, C.; Gotteland, M.; Cardemil, L. Acemannan and Fructans from Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller) Plants as Novel Prebiotics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 10029–10039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, M.-H.; Chen, Y.-H.; Cheng, M.-T.; Chiang, H.-C.; Chen, H.-W.; Wang, C.-W. Potential of Methacrylated Acemannan for Exerting Antioxidant-, Cell Proliferation-, and Cell Migration-Inducing Activities In Vitro. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aye, T.A.; Polkit, S.; Klaijan, I.; Nachanok, K.; Salil, L.; Pasutha, T. Acemannan-Containing Bioactive Resin Modified Glass Ionomer Demonstrates Satisfactory Physical and Biological Properties. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-García, G.D.; Castro-Ríos, R.; González-Horta, A.; Lara-Arias, J.; Chávez-Montes, A. Acemannan, an Extracted Polysaccharide from Aloe vera: A Literature Review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9, 1217–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai-Nin Chow, J.; Williamson, D.A.; Yates, K.M.; Goux, W.J. Chemical Characterization of the Immunomodulating Polysaccharide of Aloe vera L. Carbohydr. Res. 2005, 340, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minjares-Fuentes, R.; Rodríguez-González, V.M.; González-Laredo, R.F.; Eim, V.; González-Centeno, M.R.; Femenia, A. Effect of Different Drying Procedures on the Bioactive Polysaccharide Acemannan from Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller). Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 168, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, P.-C.; Lin, C.-H.; Chokkalingam, U.; Prakash, E.; Kao, C.-N.; Chang, C.-F.; Lin, W.-L. The Aloe vera Acemannan Polysaccharides Inhibit Phthalate-Induced Cell Viability, Metastasis, and Stemness in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 288, 117351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, N.B.; Chuenchompoonut, V.; Jansisyanont, P.; Sangvanich, P.; Pham, T.H.; Thunyakitpisal, P. Acemannan-Induced Tooth Socket Healing: A 12-Month Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeleamngam, S.; Sangvanich, P.; Thunyakitpisal, P.; Vongsutilers, V. Characterization of Quality Attribute and Specification for Standardization of Acemannan Extracted from Aloe vera for Tissue Regeneration. Thai J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 46, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razola-Díaz, M.D.C.; Aznar-Ramos, M.J.; Verardo, V.; Melgar-Locatelli, S.; Castilla-Ortega, E.; Rodríguez-Pérez, C. Exploring the Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds in Different Cocoa Powders. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.L.; Methven, L.; Parker, J.K.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Polysaccharide Food Matrices for Controlling the Release, Retention and Perception of Flavours. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 79, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buljeta, I.; Pichler, A.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Polysaccharides as Carriers of Polyphenols: Comparison of Freeze-Drying and Spray-Drying as Encapsulation Techniques. Molecules 2022, 27, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afoakwa, E.O.; Paterson, A.; Fowler, M. Effects of Particle Size Distribution and Composition on Rheological Properties of Dark Chocolate. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 226, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afoakwa, E.O.; Paterson, A.; Fowler, M. Factors Influencing Rheological and Textural Qualities in Chocolate—A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 18, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dürrschmid, K.; Albrecht, U.; Schleining, G.; Kneifel, W. Sensory Evaluation of Milk Chocolates as an Instrument of New Product Development. In Proceedings of the 13th World Congress of Food Science & Technology, Nantes, France, 17–21 September 2006; EDP Sciences: Nantes, France, 2006; p. 822. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, C. Multisensory Flavor Perception. Cell 2015, 161, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feichtinger, A.; Scholten, E.; Sala, G. Effect of Particle Size Distribution on Rheological Properties of Chocolate. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 9547–9559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deou, J.; Bessaies-Bey, H.; Declercq, F.; Smith, P.; Debon, S.; Wallecan, J.; Roussel, N. Decrease of the Amount of Fat in Chocolate at Constant Viscosity by Optimizing the Particle Size Distribution of Chocolate. Food Struct. 2022, 31, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.C.; Alfaro, M.C.; Calero, N.; Muñoz, J. Influence of Polysaccharides on the Rheology and Stabilization of α-Pinene Emulsions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 105, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckett, S.T. Science of Chocolate, 2nd ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-85404-970-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kumbár, V.; Kouřilová, V.; Dufková, R.; Votava, J.; Hřivna, L. Rheological and Pipe Flow Properties of Chocolate Masses at Different Temperatures. Foods 2021, 10, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarić, D.B.; Rakin, M.B.; Bulatović, M.L.; Dimitrijević, I.D.; Ostojin, V.D.; Lončarević, I.S.; Stožinić, M.V. Rheological, Thermal, and Textural Characteristics of White, Milk, Dark, and Ruby Chocolate. Processes 2024, 12, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thant, A.A.; Ruangpornvisuti, V.; Sangvanich, P.; Banlunara, W.; Limcharoen, B.; Thunyakitpisal, P. Characterization of a Bioscaffold Containing Polysaccharide Acemannan and Native Collagen for Pulp Tissue Regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 225, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, R.; Liang, H. Food Hydrocolloids: Structure, Properties, and Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-Y.; Hsu, S.-H.; Chokkalingam, U.; Dai, Y.-S.; Shih, P.-C.; Ekambaranellore, P.; Lin, W.-W. Aloe Polysaccharide Promotes Keratinocyte Proliferation, Migration, and Differentiation by Upregulating the EGFR/PKC-Dependent Signaling Pathways. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobek, L. Interactions of Polyphenols with Carbohydrates, Lipids and Proteins. Food Chem. 2015, 175, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.