Abstract

Agricultural leftovers from oilseed crops represent an underutilized lignocellulosic resource for integrated biorefinery. In this work, rapeseed straw (RS) and sunflower stalk (SS) were evaluated as raw materials for the simultaneous recovery of hemicelluloses, lignin, and cellulose-rich fibers. Direct soda pulping (20% NaOH, 160 °C, 45 min) or a combination of soda pulping with water pretreatment or alkaline extraction (water or 2% NaOH, 110 °C, 40 min) were the methods used in the process. Acid precipitation was used to remove lignin from the process fluids, whereas ethanol was used to separate hemicelluloses. FTIR spectroscopy, HPLC of acidic hydrolysates, and chemical composition analysis were used to analyze solid fractions and recovered biopolymers. The combination alkaline extraction–soda pulping produced the greatest material removal: 55% for RS and 70% for SS. Xylan was the main component of the isolated hemicellulose fraction: 44.86% for RS and 40.09% for SS. Paper sheets produced from the resulting pulps exhibited tensile strength indices of 35–55 N·m/g and burst indices of 1.1–2.4 kPa·m2/g, meeting requirements for hygiene and fluting packaging papers. These results prove that RS and SS are suitable feedstocks for integrated, multi-stream biorefinery, enabling the concurrent production of paper-making fibers and value-added biopolymers.

1. Introduction

Agricultural residues and byproducts represent an important category of lignocellulosic materials, and most of them are generated as post-harvest materials: stalks, stems, and straws. In temperate climate areas, the cultivation of edible oil crops is generally dominated by sunflower and soybean crops [1]. Eurostat indicates that about 20 million tons of rapeseeds were harvested in the EU in 2023 from 6.2 million hectares. In 2025, records for sunflower seed show values of 10 million tons in harvest from 4.7 million hectares in the same year [2].

The average yield of rapeseed stalks is ranging from 3 dry t/ha [3] to 8.6 t/ha [4]. In the case of sunflower, each ton of harvested seeds results in around 1.4 to 1.7 tons of stalks, which correspond to stalk yields of up to 5–6 tons/ha. Stalks represent around 33% (mass) of the dry aerial part of the sunflower plant, which constitute the leftover biomass at the combine harvester outlet [5,6,7]. Various factors, including plant density, environmental conditions, and agronomic practices, influence this yield. Large volumes of straws and stalks are produced as a result of such extensive farming operations, which can cause problems when the fields need to be prepared for the following season. Both sunflower stalks [8,9] and rapeseed straws [10,11] can occasionally be a valuable resource for field preparations for the upcoming crop. However, the general practice of the incorporation of stalks/straws into plowing has several known disadvantages that include interfering with the seedbed preparation operations and harboring pests while also increasing the chance of disease proliferation [12,13,14]. Under these circumstances, farmers have few options for properly preparing their land for the next crops: (i) the selection of proper agricultural operations and machinery type to increase depth plowing, advanced tillage to reduce the size of the stalks, and to increase the decomposition rate; (ii) the adoption of an adequate crop rotation systems; and (iii) land cleaning—harvesting the straws and stalks. That last alternative produces large amounts of lignocellulosic biomass, with high potential for valorization in bioenergy, biorefinery, and other applications [15,16,17].

Owing to their widespread availability in large amounts, sunflower stalks (SSs) [5,18] and rapeseed straws (RSs) [19,20] have attracted a lot of interest as raw materials for bioenergy and biorefinery processes [18,21]. Therefore, a remarkable volume of information is available in the literature, on both SS and RS, ranging from chemical composition [22,23,24] and diverse physico-chemical pathways [25,26,27,28] to various value-added products [29,30,31,32,33,34] and paper-making potential [3,35]. This information is very important and serves as a reference for this study, enabling both the verification/validation of the data collected and the potential to compare the outcomes, to emphasize the contributions this work has made to the advancement of the area.

This study’s goal is to present a methodical and comparative investigation of rapeseed straw and sunflower stalks as feedstocks for a multi-output, fiber-based biorefinery operating under the same processing conditions. This work combines the recovery and characterization of hemicelluloses, lignin, and cellulose-rich pulps within the same experimental framework, in contrast to the majority of other investigations that usually concentrate on a single biomass type or target a single product stream. An essential novelty is the direct comparison of the two oilseed residues in terms of solid yield, chemical composition of both solid and liquid fractions, and the purity and structure of the recovered biopolymers. Furthermore, the functional performance of the produced pulps is assessed using laboratory papermaking and mechanical testing, allowing for a clear relationship between processing configuration and end-use attributes. This study extends current knowledge on the integrated valorization of agricultural residues and promotes their application in sustainable pulp-based biorefinery by integrating comparative feedstock analysis and multi-stream product evaluation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Processing and Chemical Analysis

Raw biomass materials used in the study, rapeseed straw (RS) and sunflower stalk (SS), were collected from Romanian private farmers’ land following the post-harvest period. In Romania, sunflower is commonly harvested from late August to mid-September, while rapeseed is harvested from the end of June to the beginning of July.

The samples were cleaned of dirt, foreign plants, and any damaged or rotten parts were eliminated. After these procedures, the biomass was cut to a length of around 2 cm, deposited for a week to reach an equilibrium moisture content, and then employed in pulping or extractive studies. The 2 cm pieces of RS and/or SS were cut using standard gardening pruning scissors. The SSs were used as a whole, including the pith, which represented 10% (w/w) of the dried stalks.

Mechanical processing of solid samples, either treated or raw, as well as the resulting pulping solid material, was performed by grinding to the suitable particle dimensions requested by analytical procedures. Laboratory sheets were obtained after preliminary refining of the resulting fibrous material on a Jokkro mill. Papermaking potential evaluation was carried out by assessing the tensile and burst strengths using a Zwick Roell Z0.5 testing machine (Zwick Roell, Ulm, Germany).

Chemical analysis was performed to establish the content of main structural polysaccharides, lignin, and ash, following the experimental procedures described in our previous works [36,37,38,39,40].

The solid yield was calculated using Equation (1). Losses of each main chemical component were expressed taking into account the initial and final absolute masses, Equation (2)

where mi and mf are the o.d. weight of the solid material before and after the treatment.

where the mi and mf have identical meaning as in Equation (1), while the CCi(%) and CCf(%) are the contents of each component (i.e., cellulose, xylan, lignin, ash) in the solids obtained after the treatments and/or the combinations of treatments.

2.2. The Experimental Approach

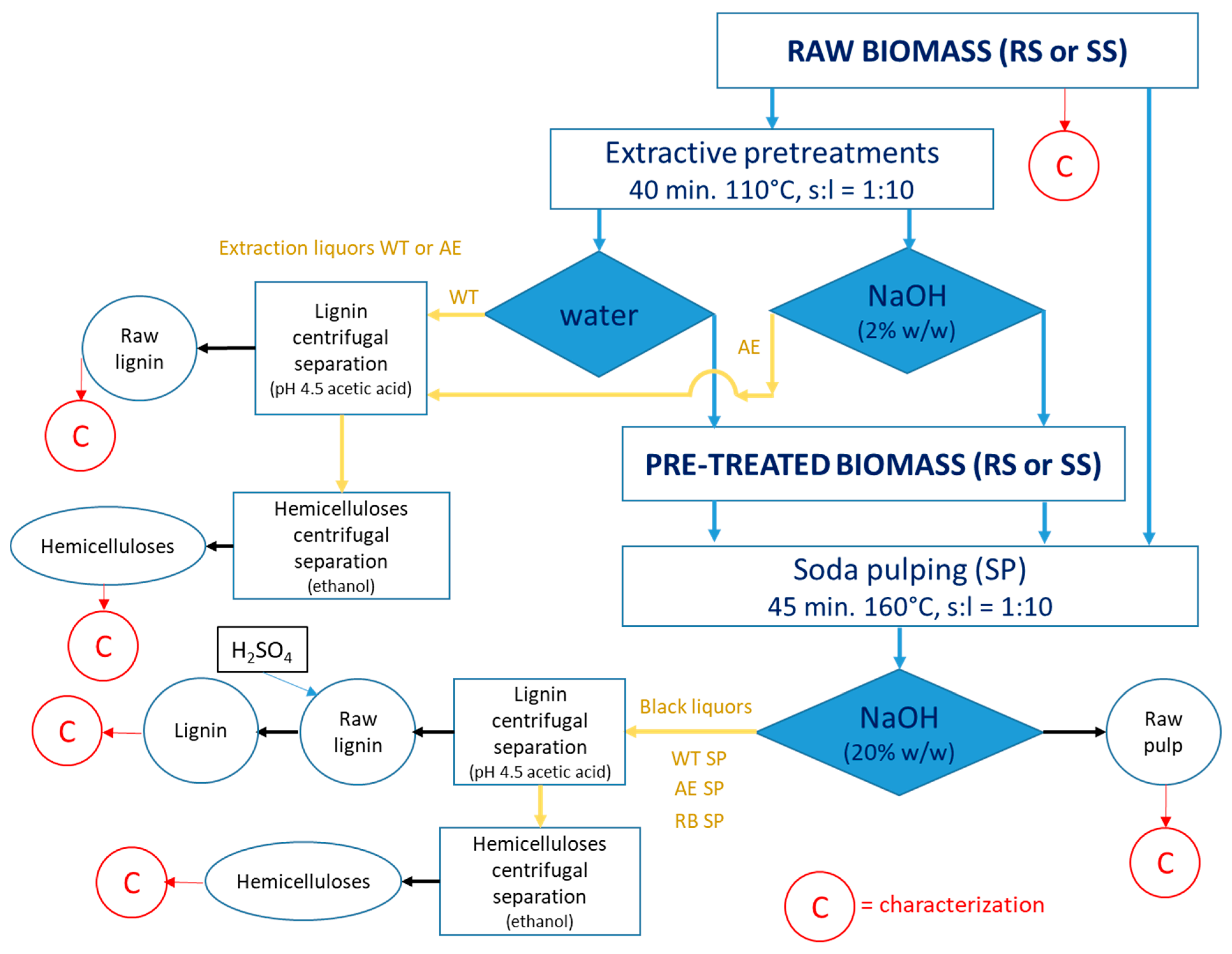

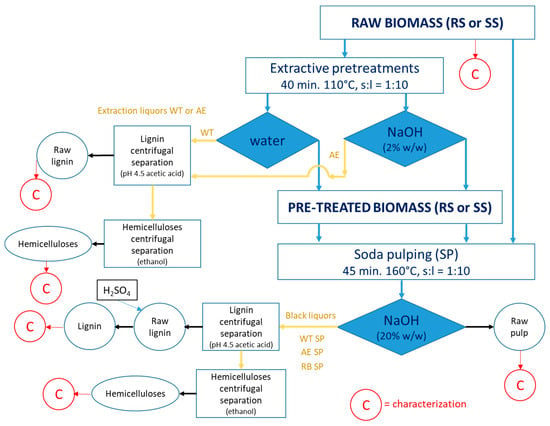

The experimental strategy is succinctly depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The experimental approach.

Hot water pretreatment is known to enhance lignocellulosic biomass conversion by inducing key structural changes such as hemicellulose solubility, increased cell wall porosity, partial lignin relocation, and improved cellulose accessibility, while the release of acetic acid from hemicellulose deacetylation creates autocatalytic conditions that promote hydrolysis.

Alkaline pretreatments modify lignocellulosic biomass mainly by removing and altering lignin, breaking ester and ether linkages between lignin and carbohydrates, and causing fiber swelling, which increases porosity and cellulose accessibility. This results in reduced biomass recalcitrance, while largely preserving cellulose; however, severe alkaline conditions can lead to partial hemicellulose loss, carbohydrate degradation, and the generation of inhibitory salts that may affect downstream processing.

While alkaline pretreatment is better for lignin disruption and delignification, hot water pretreatment works better for removing hemicellulose. Therefore, the working conditions for both water and diluted alkaline pretreatments should be carefully chosen when the aim is to convert lignocellulosic biomass to multiproduct. The authors’ prior biomass processing experience with wheat straws, corn stalks, alfalfa stems [36,37,38,39,40], and preliminary trials were used to determine the soda pulping and pretreatment conditions. The study’s goal to produce a range of products, such as hemicellulose-derived polysaccharides, lignin, and papermaking fibers, was another crucial factor in choosing the parameters.

A stainless-steel laboratory rotary autoclave type reactor (digester) was used to carry out the initial treatments of RS and SS, namely water treatment (WT) and alkaline extraction (AE). The autoclave was charged with the 300 g of oven-dried (o.d.) biomass (SS or RS), and the corresponding amount of water or sodium hydroxide solution (2%) necessary to achieve a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10. The reactor was heated to the preset temperature of 110 °C and maintained there for 40 min. After the treatment, the reactor was degassed, and liquid samples (extraction liquors) were removed for additional processing and analysis. The resulting solid samples (pre-treated stalks of RS or SS) were washed to remove the dissolved components and preserved for pulping trials. Both raw and pre-treated SS and RS were used in the soda pulping (SP) studies that were performed in the same equipment as the pretreatments. The solid-to-liquid ratio (s:l) was 1:10, at an alkali charge of 20% expressed as NaOH units. The pulping time was of 45 min at an established temperature of 160 °C. The reactor was degassed after the pulping period, and the black liquor and fibrous residues (soda pulp) were recovered for further analysis (HPLC of acidic hydrolysates) and processing, beating, and sheet forming. A Shimadzu Nexera LC-40D (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) liquid chromatography system equipped with a Shodex SP0810 column (300 × 8 mm, 8 μm particle size, Resonac, Shunan, Japan) heated to 65 °C was employed for the required HPLC analyses.

The lignin and hemicelluloses were recovered from the extraction liquor and from the black liquor and further characterized (Figure 1). In the first step, lignin was precipitated by pH reduction to 4.5 with acetic acid and then separated by centrifugation. A Sorvall GLC2 centrifuge (Kroslak Enterprises, Riverview, FL, USA) equipped with an HL-4 rotor, with a CF value of 2012, 3000 r.p.m., was used for solid precipitate separation. The remaining supernatant was then treated with ethanol to induce the hemicelluloses precipitation. A second centrifugation ensured the hemicelluloses separation. The remaining supernatant was sent to ethanol recovery.

The separated HC samples were initially characterized by FTIR, while HPLC analysis of their sulfuric acid hydrolysates was used to reveal purity and some of the structural features. The raw lignin samples were subjected to purification to reveal the acid-insoluble lignin content and further characterized by FTIR spectroscopy. The FTIR spectra of HC and lignin samples were recorded by using an Agilent Cary 630 spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in the transmission mode. The FTIR spectra of hemicelluloses as well as lignin samples were recorded by an Agilent Cary 630 (Santa Clara, CA, USA) using the potassium bromide pellet technique on disks containing finely ground samples at 1% content.

All experiments were conducted in triplicate unless otherwise specified, following established standard methods. The maximum acceptable relative standard deviation was set at below 5%.

The following abbreviations were used: RB = raw biomass; TB = pre-treated biomass; RL = raw lignin; The associations among the abbreviations are meant to (i) indicate the source constituent and the process supported (e.g., WT RS = water pre-treated rapeseed straws stalk; AE SS = alkali-extracted sunflower stalk); (ii) indicate the separated component and the extraction procedure (e.g., AE RL = alkaline-extracted raw lignin; SP RL = soda pulping-extracted low lignin); (iii) indicate the separated component, the extraction procedures, and the source constituent (e.g., AE SP RL SS = raw lignin obtained from sunflower stalks after alkaline extraction and soda pulping; WT SP HC RS = hemicelluloses obtained from rapeseed straws after water pre-treatment and soda pulping). C = chemical characterization.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition of Raw Materials

The chemical composition of the raw lignocellulosic biomass used in the study is displayed in Table 1 and Table 2, along with relevant literature data for comparison.

As anticipated, due to a large number of rapeseed varieties [41], the RS chemical composition of the main components (Table 1) displays a comparatively wide range of values. The cellulose content varies from 28% [42] to 49.2% [43]. The holocellulose content (although reported as such in a small number of studies) varies from 66.0 to close to 80% [3]. The material under study revealed a much lower holocellulose content, although the results on total hemicelluloses fall within the range presented by most of the studies [44,45].

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the raw RS: current study vs. literature data.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the raw RS: current study vs. literature data.

| Component (%) | Current Study RS | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [29,46] | [3,43] | [47] | [44,45,48] | [49] | [42] | ||

| Cellulose | 37.10 | 38.50 | 41.60–49.18 | 35.01 | 34–35 | 34.08 | 28.00–31.60 |

| Holocellulose | 54.95 | 66.00 | 78.90 | 69.80 | - | - | - |

| Total hemicelluloses | 17.85 | - | 37.30–14.55 | 34.80 | 18.70–21.00 | - | 17.40–19.0 |

| Xylan | 11.36 | 18.60 | - | 19.90 | 16.16–18.60 | 17.04 | 13.2 |

| Galactan | 1.37 | - | - | 1.18 | 2.54 | - | 1.90 |

| Arabinan | 2.23 | - | - | 0.94 | 1.44 | - | 1.20 |

| Mannan | 2.88 | - | - | 2.16 | 1.76 | - | 1.20 |

| AIL | 29.10 | 13.00–19.20 | 16.1–17.65 | - | 15.30–28.70 | 21.30 | 16.20 |

| Ash | 3.37 | - | - | - | 5.70 | 16.20 | 6.70 |

The majority of the hemicelluloses in RS (more than 60%) are represented by xylan. The presence of additional sugars (galactose, arabinose, and mannose) in the acidic hydrolysate that underwent HPLC examination suggests that the relevant polysaccharides were also present in the RS samples under analysis.

The HC content variations can be associated with various factors, including environmental adaptation and cultivar [36]. The RS biomass used in the study displays higher values for the acid insoluble lignin (AIL) compared to other literature sources; however, the reported range for the polymeric aromatic component is also wide, as mentioned by [44,45]. Last of all, despite some publications indicating ash concentrations as high as 16% [49], the ash content value of this study RS does not approach 5%.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the raw SS: current study vs. literature data.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the raw SS: current study vs. literature data.

| Component (%) | Current Study SS | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7] | [50] | [51] | [52] | [53] | [54,55] | ||

| Cellulose | 31.23 | 34.19–40.67 | 30.80 | 41.40 | 33.45 | 54.50 | 30.80 |

| Holocellulose | 49.86 | - | - | 70.30 | 55.16 | 64.20 | - |

| Total hemicelluloses | 18.63 | 9.78–21.28 | - | - | 21.70 | 9.70 | 20.20 |

| Xylan | 14.00 | 7.83–10.30 | 12.40 | - | 16.65 | - | 15.3–16.1 |

| Galactan | 1.39 | 0.85 | - | - | 2.40 | - | 1.70 |

| Arabinan | 2.30 | 0.05–0.48 | - | 0.87 | - | 1.10–1.40 | |

| Mannan | 0.94 | 1.07–1.46 | 1.79 | - | 0.80–1.00 | ||

| AIL | 25.47 | 18.20–21.60 | 15.10 | 18.30 | 12.60 | 13.90 | 14.60–16.60 |

| Ash | 10.04 | 1.50–2.48 | - | 8.90 | 7.77 | - | 8.80–9.60 |

In case of sunflower stalks, it was discovered that the cellulose content was roughly one-third of the oven-dried material, which is generally consistent with the published research (Table 2).

Holocellulose represented about half of the oven-dried while hemicelluloses represented less than one-fifth of the SS biomass. The xylan showed to be the dominant polysaccharide among hemicelluloses. Small amounts of galactan, mannan, and arabinan were found to contribute to the hemicelluloses fraction. When it came to lignin content, the results were higher than those found in other references; just one study found a lignin percentage of more than 20% [7].

The amounts of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, extractives, ash, and other constituents in agricultural residues (which include more than just rapeseed or sunflower stalks) depend on a number of factors, including plant variety (cultivar), soil properties, agricultural treatments (such as irrigation, fertilization, and herbicide application), climatic conditions (such as season alternation and precipitation level), harvesting time and practices (such as plant maturity at harvest, mechanical handling, storage), and exposure to biotic and abiotic stresses (e.g., molds and mushrooms, freeze–thaw cycles, humidity, drought). The morphological differences between the RS and SS would also influence their behavior during physico-chemical treatments.

3.2. The Effect of the Treatments on the Chemical Composition of the Resulting Solid Materials

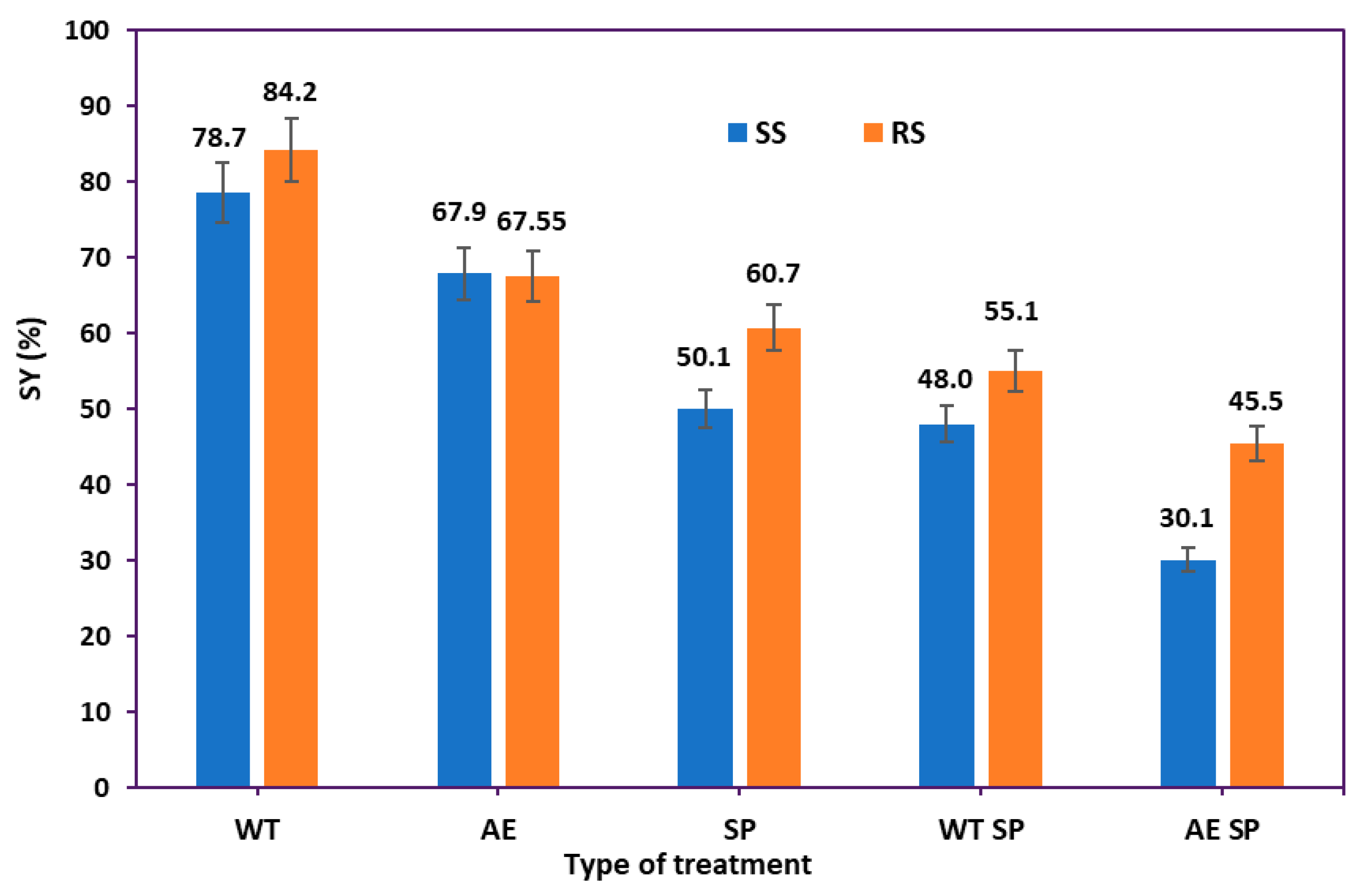

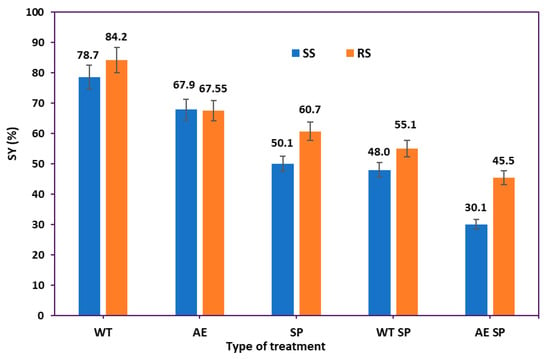

The selected processing methods had a significant impact on the solid yield (SY %) and chemical composition of the final solid materials. The solid yield (SY, %) was determined by gravimetric means. Figure 2 displays the overall impact on the solid yield of either individual treatment phases (WT, AE, or SP) or the combinations (WT SP or AE SP).

Figure 2.

The treatments solid yields: RS vs. SS.

As shown in Figure 2, the combination of alkali extraction and soda pulping proved to be the most effective; for the SS, the material loss was around 70%, while for the RS, the total loss was over 55%. When the WT and SP methods were combined, around half of the starting biomass was removed for both RS and CS. Additionally, it can be noticed that soda pulping and alkaline extraction both result in considerable losses, whereas water treatment eliminates roughly 16% to 21% from RS and SS, respectively. Overall, the RS behaved better, meaning that almost all types of treatments induced lower material loss than for the SS. The yield values correlate relatively well with the type and severity of the treatment [56]. There is also an acceptable correlation with the literature data, which range in the interval from 35 to 95% solid yield values, also in strong dependence on the process parameters and on the RS and SS initial chemical composition [48,57,58].

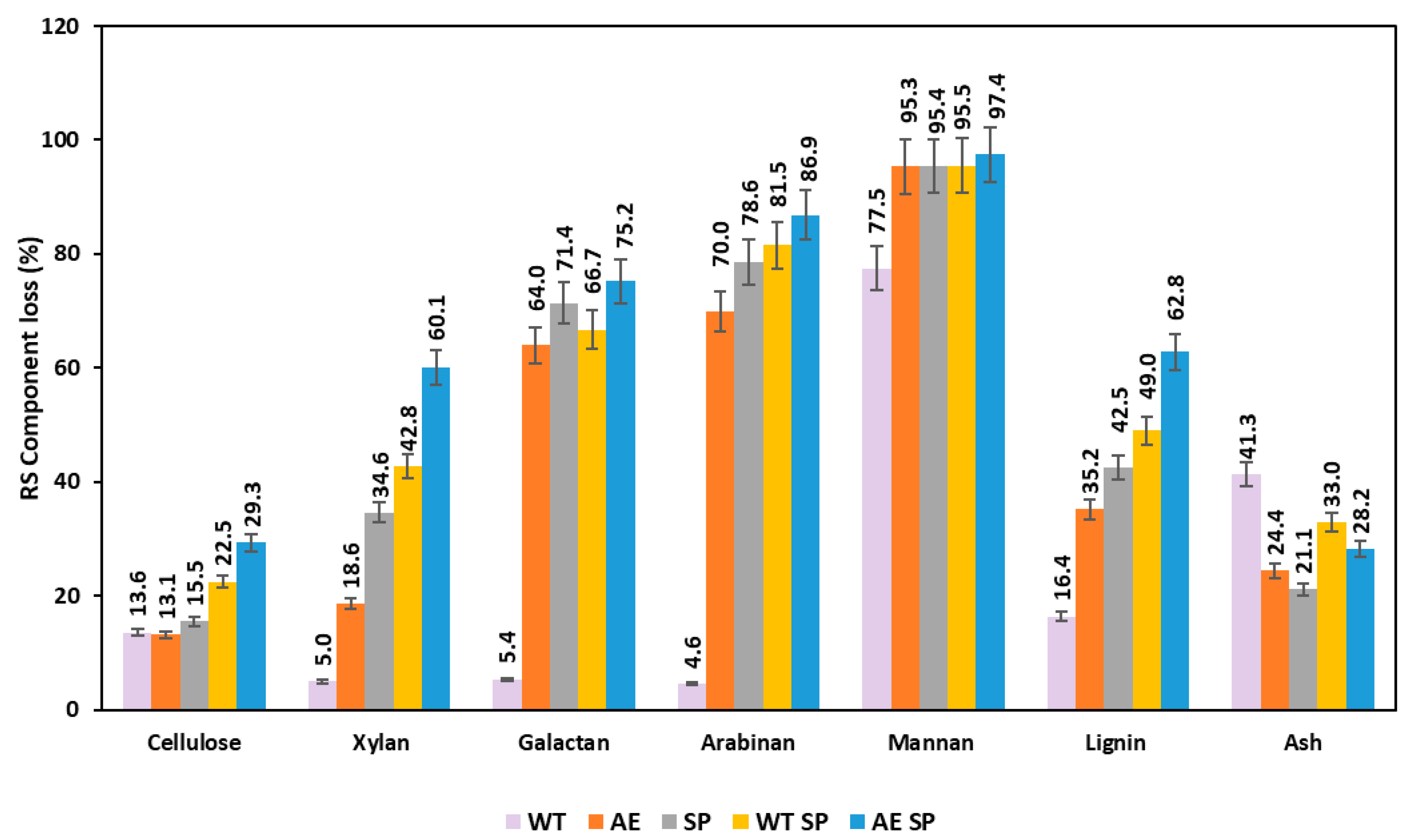

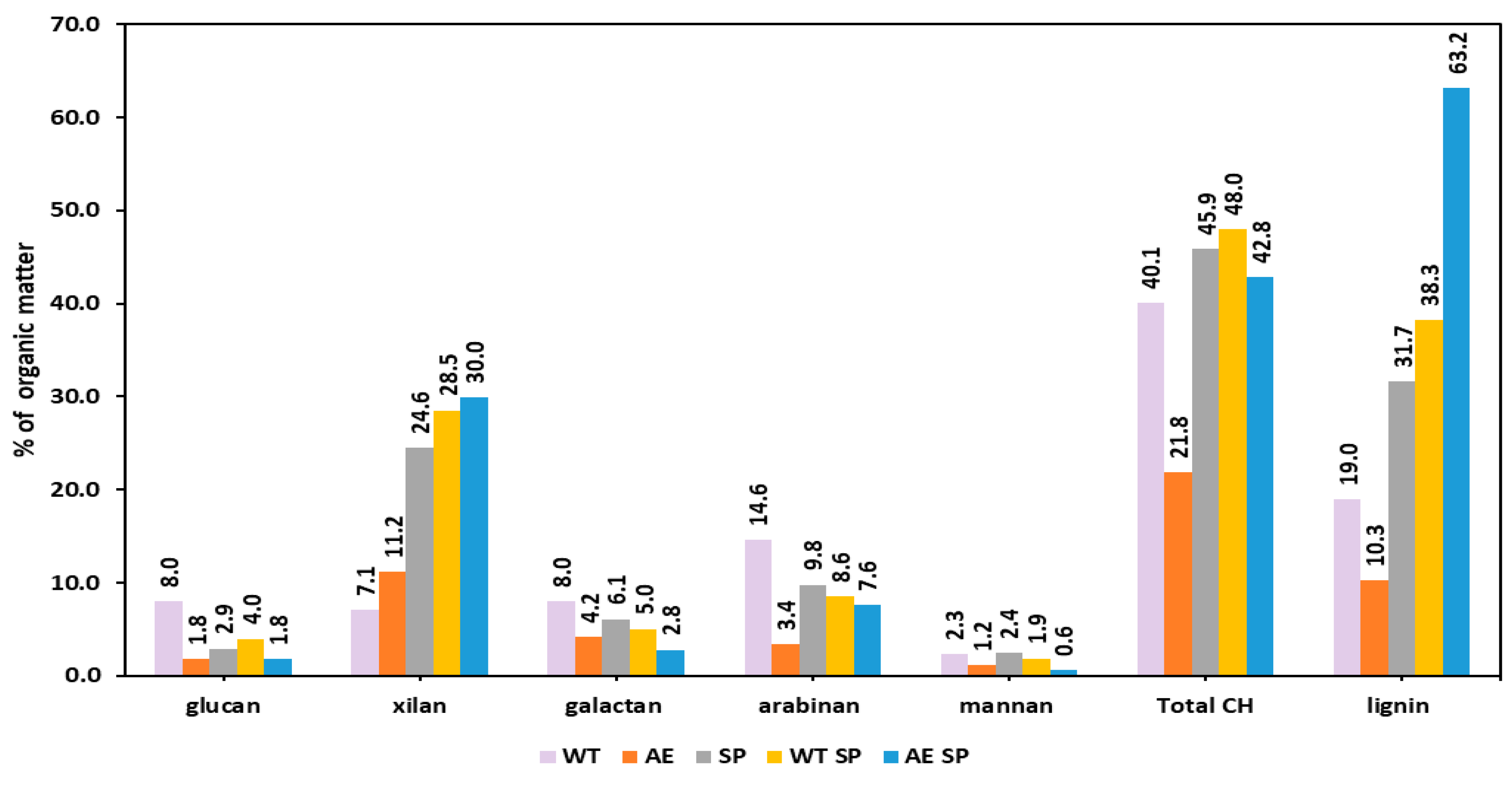

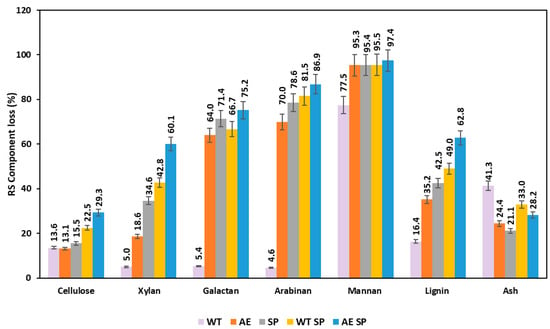

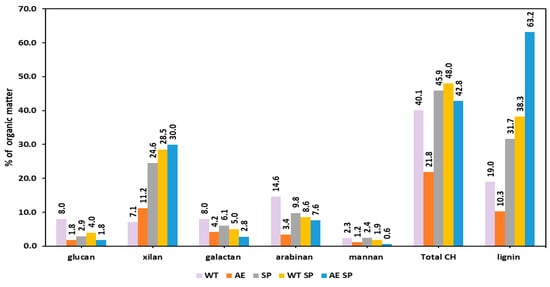

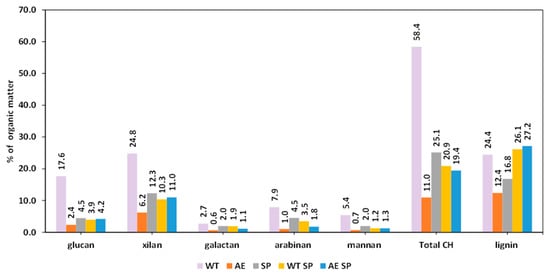

The variations of the chemical composition resulted as losses occurring after the biomass treatments and subsequent analysis of the solids is displayed in Figure 3 and Figure 4 (for RS and SS). Figure 3 shows that all the treatments induce significant losses of both polysaccharides and lignin. However, this happens to a different extent depending on the treatment type and component. For RS and in case of cellulose, the single extractive stages such as WT or AE lead to losses around 13%. Further pulping increases the overall loss to 22.5 and 29%. Hemicelluloses are much more severely impacted and losses range from about 5% in WT for xylan, galactan and arabinan to as high as 60–80% in alkaline treatment, soda pulping, and combinations. Lignin is removed at a rate of 16% in WT but the amount changes to higher values in AE and SP or combinations (WT SP, AE SP). The performed preliminary extractive treatments also record a high effect of removal on the inorganics (ash).

Figure 3.

Effect of the treatments expressed as losses (%) on the resulting RS biomass chemical composition.

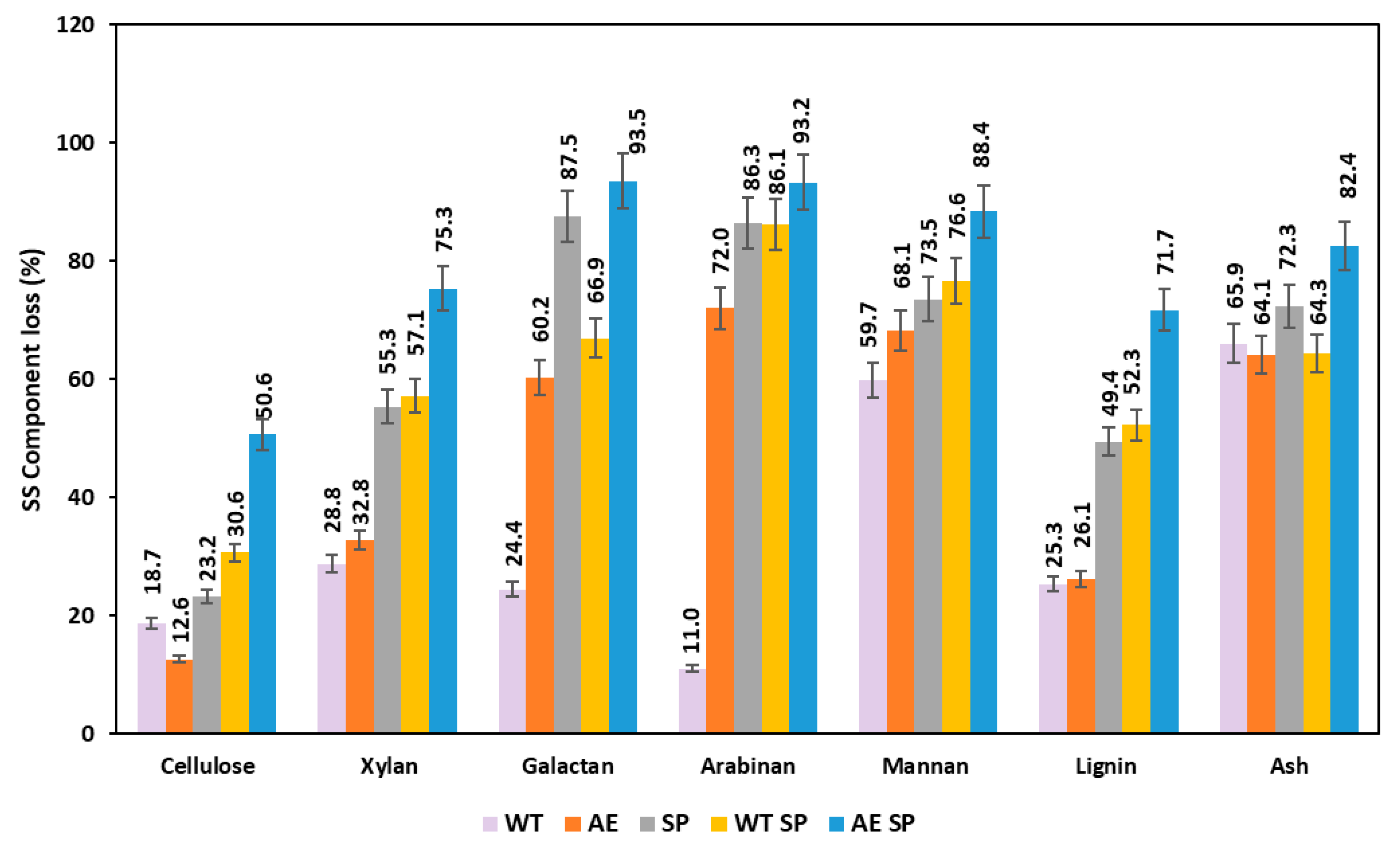

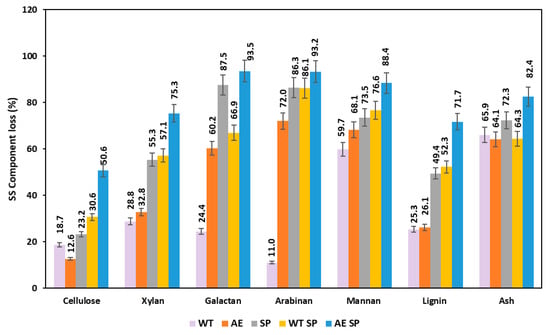

Figure 4.

Effect of the treatments expressed as losses (%) on the resulting SS biomass chemical composition.

Karagöz et al. performed alkaline peroxide treatment of RS and reported an increase in cellulose from 29.74% to 59.34% and for xylan from 13.96% to 34.18%. The reported lignin removal rates reached a maximum of 35% [57]. Nevertheless, the overall loss was not reported in the study.

Diaz et al. performed similar hydrothermal treatments on rapeseed stalks in which yield values ranged from 51% to 71% but the study does not mention the overall loss of any component type. However, after performing some calculations, the loss rate of glucan and xylan seems to be in the range of 30–50% depending on the severity [48]. Similar values were mentioned in the studies of other authors [43,47,59,60,61].

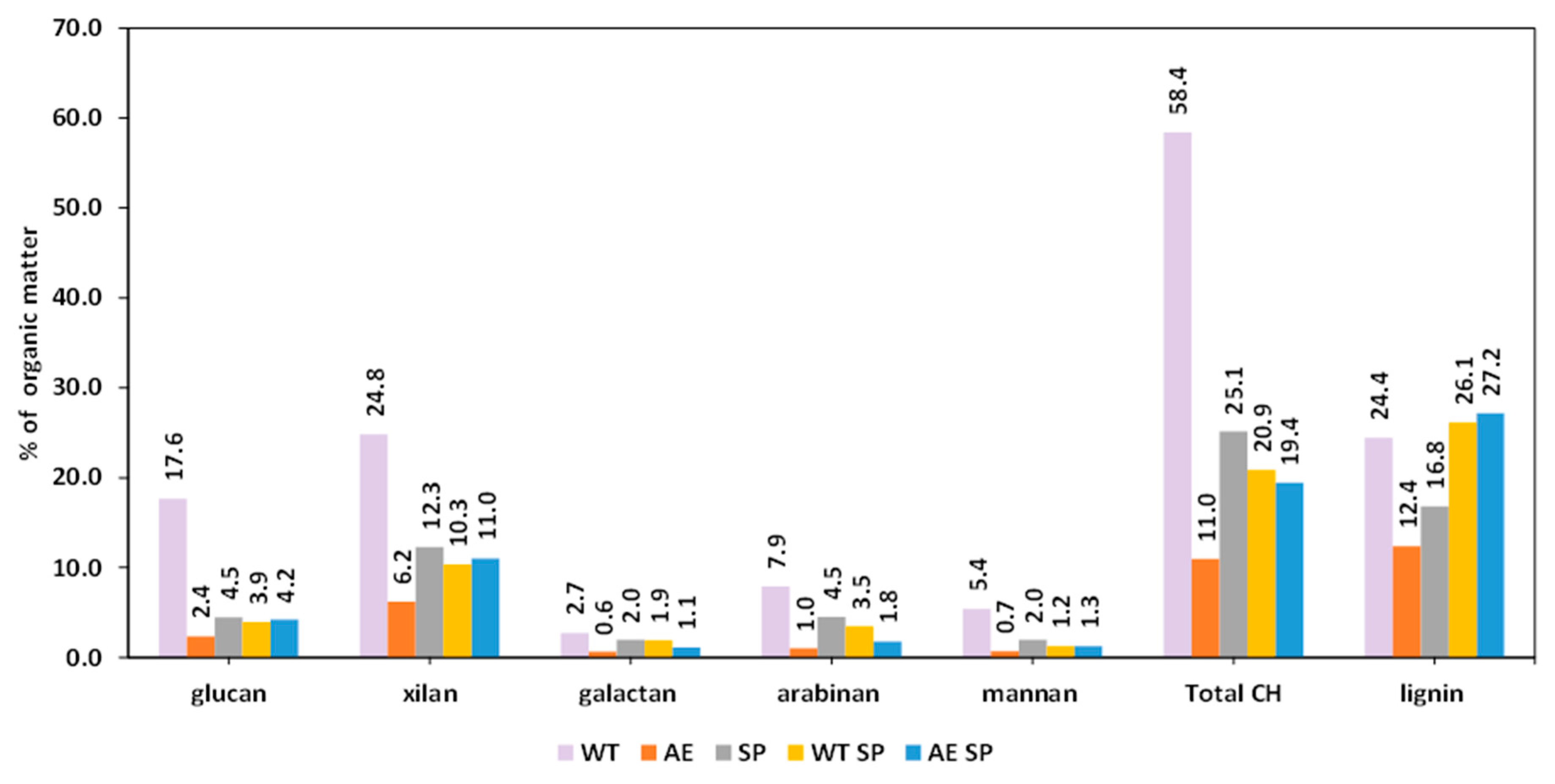

Figure 4 displays the losses of polysaccharides, lignin, and ash as an effect of the experimental treatments on the sunflower stalks. The data show that this type of biomass is more sensitive to all types of treatments than RS, bearing in mind the fact that, in general, the losses are higher with minor exceptions. In the case of SS cellulose, the determined losses were up to 50%, while xylan losses ranged from 29% to 75%.

The losses of other carbohydrates were also higher in comparison with RS biomass for the similar type of treatment or combinations. Lignin removal in the case of SS experimental processing exhibited higher values than RS, with the minor exception found in the case of AE treatment. The behavior of SS under the experimental treatments is to some extent comparable with the existing literature studies, although most of the authors performed the treatments in more severe conditions. Higher temperatures were used, to remove hemicelluloses and lignin, and to increase accessibility of the resulting material to enzymatic or microbial conversion. In this respect, Yang and coworkers reported that water treatment of SS at 140 °C for 60 min induced 11% cellulose and 27% xylan loss, while lignin was removed at a rate of 13% [50]. Higher loss values of cellulose and xylan (20–30%) were found in case of acid treatment of SS by La Rubia et al. [62].

3.3. Chemical Composition of Liquors Resulting from Treatments

The chemical composition of the liquid fraction resulting from the performed treatment on RS and SS biomass included carbohydrates, both as oligomeric residues, as in the case of the water treatment liquor, and also as dissolved polymeric hemicelluloses, lignin, and degraded lignin [63]. A relatively important portion of the removed and dissolved fraction of the studied biomass is represented by organic derivatives of both polysaccharides and lignin, which could not be further removed by acid precipitation and subsequent ethanol treatment.

The distribution of lignin and carbohydrate fractions dissolved in the aqueous extraction of RS (Figure 5) and SS may show noticeably different values (Figure 6). When it came to rapeseed stalks, the concentration of dissolved organic matter (OM) in WT liquor was approximately 2 g/L, whereas in SS water extraction liquor, it was 5.49 g/L. The results are consistent with those in Figure 2, which displays the SY % values, as well as with a number of other studies in the literature, even though the majority of the studies concentrate on some more severe treatment settings [63].

Figure 5.

The chemical composition of the organic fraction dissolved in the extraction and black liquor resulted from RS treatments.

Figure 6.

The chemical composition of the organic fraction dissolved in the extraction and black liquor resulted from SS treatments.

The carbohydrate fraction in the case of RS represented about 40% of the dissolved OM, while in the case of SS, the % was higher to about 58%. The primary sources of carbohydrates in the WT liquor of RS were either xylan or glucan depolymerization as a result of autohydrolysis, or arabinose branching loss [64]. The results show some similarities with those obtained by Svärd and coworkers [65] which experimented with rapeseed stalks having about 49% cellulose and 20% xylan, and 19% lignin. Under acidic and water extraction conditions, the mentioned authors obtained extracts with 5–6% xylan in solid organic matter. Svärd and coworkers also performed alkaline extraction on RS, which yielded dissolved organics that contained 18% xylan and from 11% to 22% glucan depending on the severity of the treatment.

The differences observed for the SS WT liquor sugar distribution in the dissolved organic matter may be explained by the distinct distribution and structure of polysaccharides in SS. The sunflower stalks contain about 10% pith that is composed of various structural pectin and an easily hydrolysable cellulose fraction [66,67]. As a result, the WT liquor OM is composed of about 17.6 glucan-derived oligomers but also includes considerable amounts of xylan and arabinan residues.

The alkaline extraction of RS and SS resulted in liquors richer in organic material than those obtained from WT. This is explainable by the ability of alkali to dissolve a higher amount of both carbohydrates and lignin but also of other components. The OM content of AE liquors was several orders of magnitude richer (29.8 g/L for RS and 24.5 g/L for SS), which constituted between 11% and 22% carbohydrates. More than a half of the dissolved carbohydrate is represented by xylan. The lignin fraction represented 10–12% of the dissolved OM. However, xylan is more prevalent in dissolved organic matter for RS than for SS.

Although there are some distinctions between SP and alkali extraction, SP is still another kind of alkali biomass treatment. Since the objectives of SP differ from AE, the conditions at least in terms of temperature and duration, are also different. The SP follows the liberation of the cellulosic fibers and conversion of biomass into pulp, a raw material for the papermaking process. These result in a higher amount of both lignin and carbohydrates removed from biomass during the process. The dissolved biomass components also suffer various degradation reactions leading to depolymerization and conversions. This is also valid for the subsequent liquors obtained either from direct pulping or from WT or AE associated with pulping. The preliminary WT or AE treatment increases the overall loss of material during the process. The resulting black liquors after WT SP or AE SP contained less dissolved organic material than the black liquors after SP of the untreated biomass. An explanation for this is the fact that under the experimental conditions, a considerable part of RS or SS was already removed. In the case of lignin, the remaining fractions may also be altered in some manner so that resistant lignin alkali is formed [16].

The SP black liquor of RS showed a lower amount of OM than similar liquor derived from SS. The content of carbohydrates in organic matter changed, but the changes did not occur in similar fashions for each type of them. Xylan content increased for both OM of black liquor of RS SP WT and also for RS AE SP.

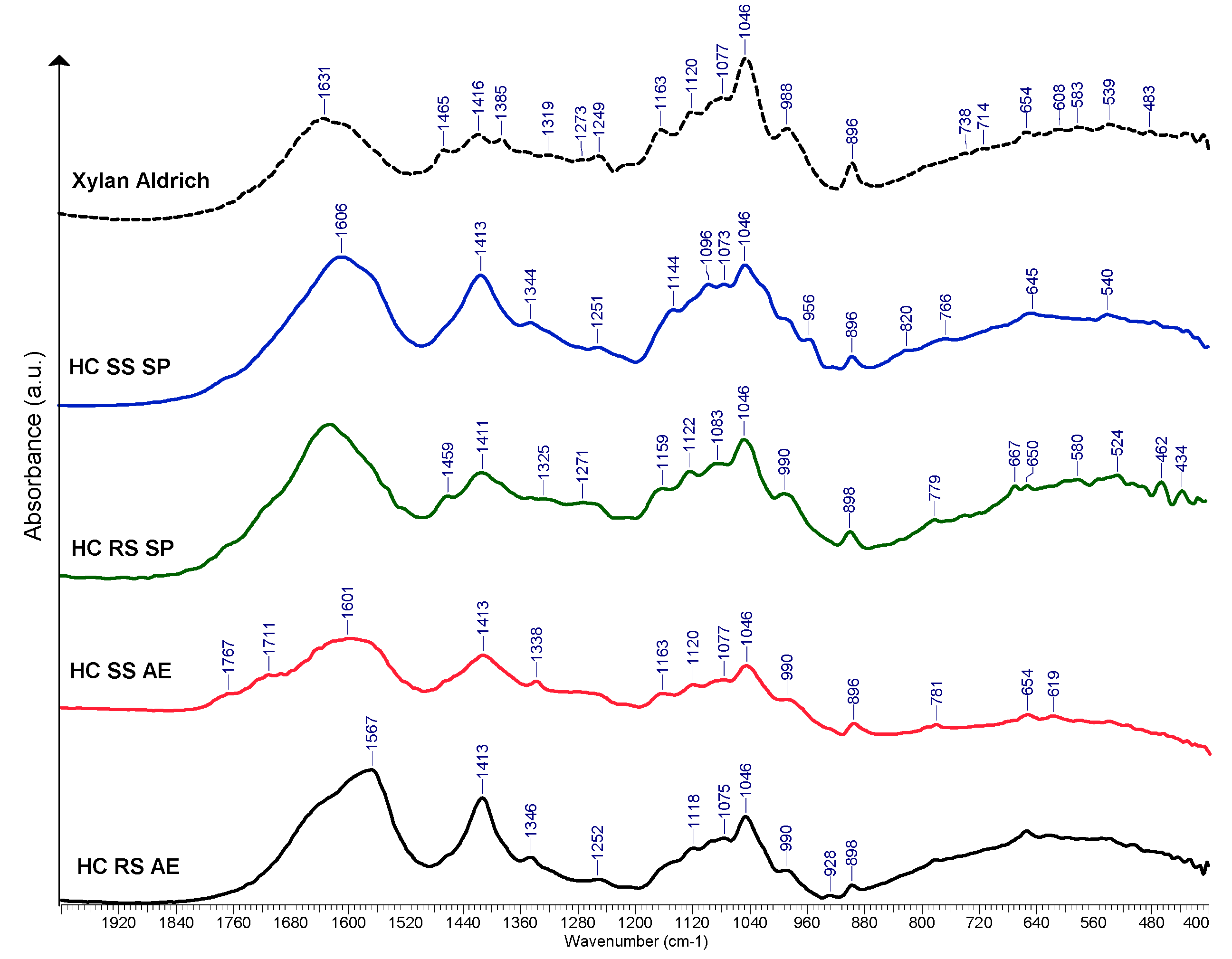

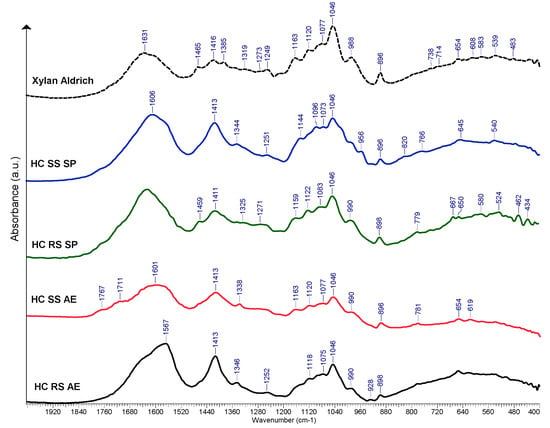

3.4. Characterization of the Recovered Hemicelluloses and Lignin

FTIR spectroscopy results for the hemicelluloses samples obtained from rapeseed and sunflower stalks are displayed in Figure 7. Since the spectra contained similar absorption bands, several of them were selected as representative. For all of the spectra, a band at 898 cm−1 was identified. This band is characteristic of the vibration of the β-glycosidic bond between the anhydro-xylose units. The wide band at 1625–1650 [68] cm−1 occurred due to absorbed water. In general, the bands differ in their intensities, and some shifting occurs, suggesting the differences in the chemical composition of the samples. Other absorption maxima that were common in the spectra were assigned as follows:

Figure 7.

Selected FTIR spectra of HC derived from RS and SS vs. commercially available HC sample (xylan from beechwood), a.u. = arbitrary units.

- 990–998 cm−1 can be assigned to C-C and C-O ring and side group vibrations of galactan and mannan branching [69];

- 1046 cm−1 may be assigned to C-O-C symmetrical and asymmetrical stretching [70];

- 1079–1163 cm−1 peaks are often associated with the branching of arabinose and galactose units [71];

- Bands or shoulders at ~1270 cm−1 could be associated with the lignin residues, although no particular lignin peaks are visible at other wavenumber values such as 1510 or 1600 cm−1 [72];

- Band and shoulder occurring at ~1410 cm−1 are assigned to bending vibrations of C-H [73].

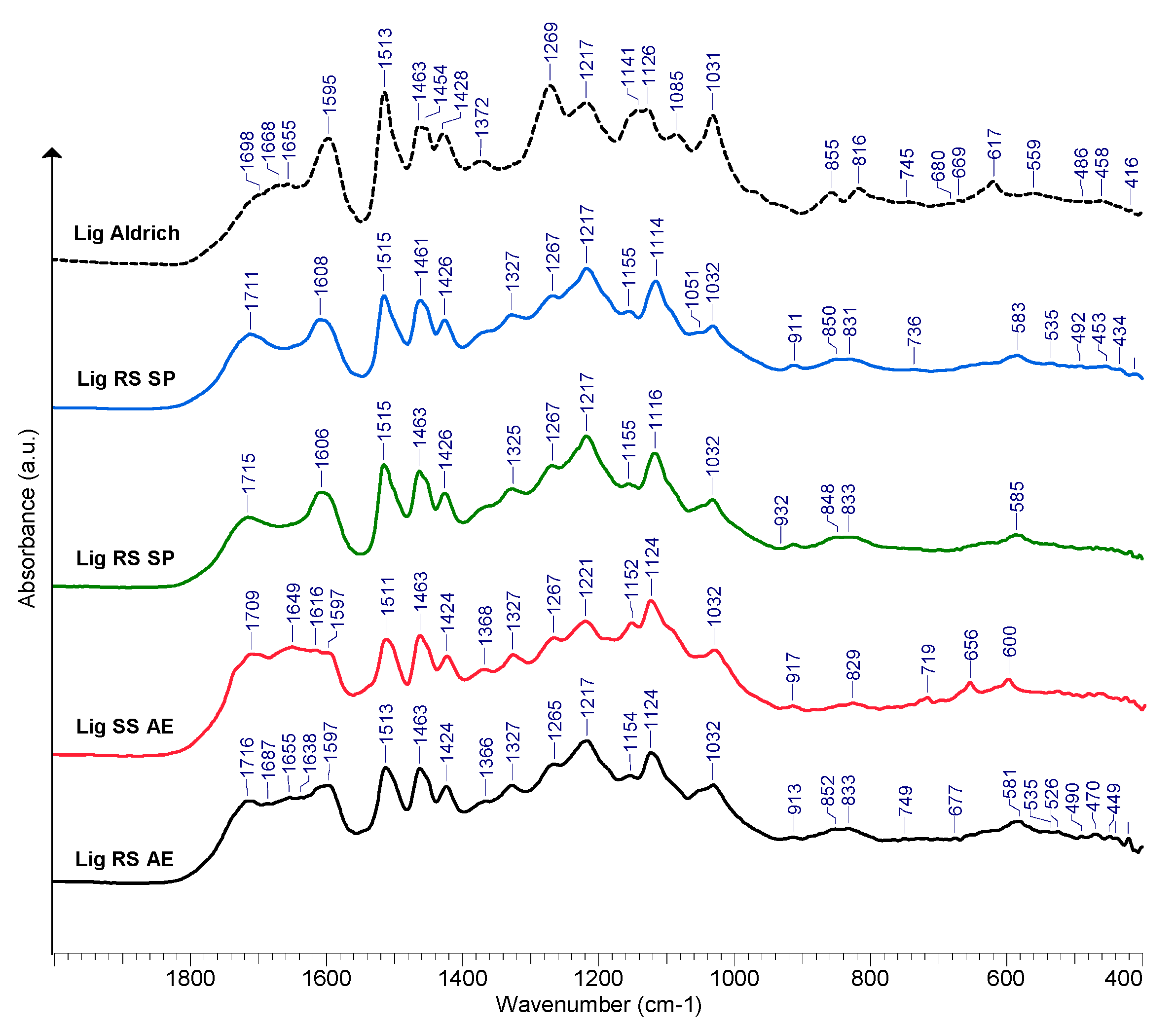

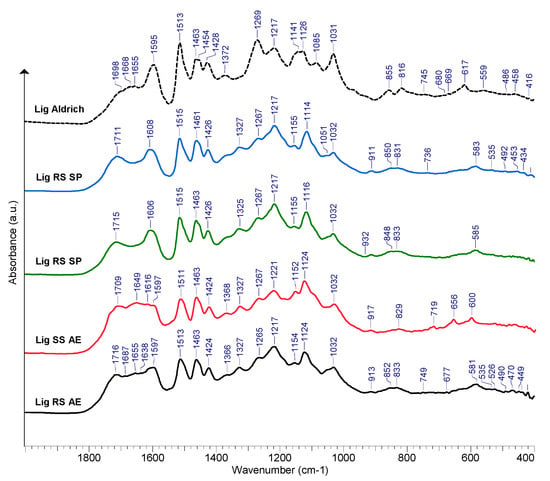

A selection of the FTIR spectra recorded for the purified lignin samples of RS and SS is displayed in Figure 8. A broad absorption band at about 3400 cm−1 was seen in all of the recorded lignin spectra, which was caused by the stretching vibrations of the O-H bond in phenolic and alcoholic hydroxyl. Peaks at approximately 2930 and 2850 cm−1 were produced by the C-H stretching vibration of methyl and methylene [74,75].

Figure 8.

FTIR spectra of purified lignin samples obtained from RS and SS processing.

The carbonyl stretching (C=O) in aldehydes, in particular on the saturated side chains of lignin, is suspected to be the causes of the ~1715 cm−1 peaks [76,77]. The lignin samples isolated from the alkali extraction liquors also show peaks at ~1680 cm−1 that may be attributed to conjugated carbonyl group stretching [78,79]. The aromatic skeletal vibrations’ absorption maxima are visible in all lignin samples; FTIR spectra are observable at 1597, 1608, and ~1513 cm−1 , while the 1424–1428 cm−1 peaks result from the C-H in-plane deformation vibration associated with aromatic ring stretching [80,81].

The peak at about 1463 cm−1 may be associated with the asymmetric bending of the methyl and methylene groups [82]. The absorption maxima at 1366–1368 cm−1 may be assigned to the symmetric C-H bending of the methyl groups in the methoxy groups [83]. The peaks of the S-ring are revealed by the presence of the ~1325–1327 cm−1 peak (C-O stretching), while ~1265 cm−1 absorption maxima evidence the presence of the G-type ring [84,85]. The absorption at 1217–1220 cm−1 is potentially generated by aryl breathing and stretching vibrations of C=O and C-C bonds [81,86].

The peaks at about 1155 cm−1 indicate that the studied RS and SS samples are of type HGS lignin [87,88,89]. This peak does not appear in the reference lignin (Sigma Aldrich, Chemie GmbH, Taufkirchen, Germany, PN 370959). Peaks seen at 1032 cm−1 are present as a result of the C-O stretching vibrations of the primary (γC) alcohols [77]. The peaks at 919–917 cm−1 were assigned to C-H vibrations [88]. According to Shi et al. [85], the presence of the absorption at ~829 cm−1 should be assigned to C-H out-of-plane vibrations in H-type lignin units. The bands occurring in the range of 1210–1230 cm−1 may also be assigned to various stretching vibrations of either C-C, C-O, and C=O [90]. The absorption maxima occurring in the range of 1080–1030 cm−1 may be associated with the various vibration modes of the C-O in alcohols and phenols [90,91,92].

The chemical composition of the graded ethanol-precipitated hemicelluloses fraction is revealed in Table 3 and Table 4. The RS stalk hemicelluloses were found to be a xylan-based type. The small percentages of galactan, mannan, and arabinan indicate that the xylan is branched by such anhydro-sugar short chains.

Table 3.

Chemical composition of HC samples obtained from alkaline liquors after RS processing.

Table 4.

Chemical composition of hemicelluloses samples obtained from alkaline liquors of SS processing.

The amount of glucose present in the hydrolysate indicated the potential branching of the xylan with glucose anhydro residues but the amount could be a result of the co-precipitation of such oligomers during ethanol separation. The percentage of xylan increases with the severity of the treatment, while the amounts of galactan, arabinan, and mannan decrease.

The hemicelluloses obtained from SS treatment liquor (Table 4) present almost the same sugars in their acidic hydrolysate, except for mannose, which was not determined (n.d.). Such a finding indicates that mannan-type chain branching is removed—mannose was also found as a neutral sugar in SS hydrolysate subjected to the HPLC separation. The amount of the glucan-type oligomers in SS hemicellulose samples increased with the type of extractive process.

The chemical composition of the separated HC samples is rather similar to that reported by other authors in works concerning either the same biomass type or different. Some differences still exist, given the objectives of the work, the separation procedures, and the analytical ones. On the other hand, no previous works were found concerning the isolation and characterization of the HC from the pulping black liquor of either RS or SS. Svärd and coworkers reported the extraction of HC from rapeseed straws under close conditions with those specified in this study, having xylan contents between 33% and 57% [30]. According to the authors, two main types of hemicellulose-rich fractions were extracted from rapeseed straw biomass: Galactoglucomannan-rich fractions were obtained from hot water extraction liquor, while glucuronoarabinoxylan-rich fractions were obtained from alkaline extraction.

Much more recently, Prado and coworkers used alkaline extraction (50 °C, 0.75 M NaOH, and 60 min) to isolate HC from SS for further use as cultivation media for Bacillus Subtilis. Although not fully characterized, authors revealed that more than half of the isolated carbohydrate consisted of xylan [93]. The RS and SS HC samples described in this work showed structural similarities with the alkali-extracted HC samples from pear pomace and subsequently purified by dialysis that contained 39% xylan, 27% glucan, and 17.5% galactan. The arabinose and mannose branching represented 0.5–8.75% of the content [94].

A more facile comparison of RS and SS alkali-extracted hemicelluloses can be made, considering the works dedicated to the extraction and separation of such polysaccharides from cereal straw (most often wheat) and corn stalks. Under these considerations, the paper of Li and coworkers [95] reveals alkali-extracted hemicelluloses of corn stalks, mostly of xylan type. After applying various fractionation techniques, 80% xylan purity of hemicelluloses can be obtained [96]. Wheat straw may also be used to obtain high-xylan-content hemicelluloses as described by Sun and Tomkinson [97]. Integration of the hemicelluloses’ extraction in pulp production adds black liquor as a potential hemicellulose source, as reviewed by Oriez et al. [98]. Purity of the obtained samples in terms of xylan content depends on pulping parameters, but also on the used biomass, and generally ranges from 25 to 55% [99,100].

The chemical compositions of the lignin samples obtained from alkaline liquors after RS and SS processing are presented in Table 5 and Table 6. The importance of lignin recovery from pulping black liquor has gained importance in the context of fiber-based refinery. Recovery of lignin from soda pulping is crucial because it provides a second byproduct that may be processed to obtain materials and chemicals [101]. The nowadays lignocellulosic biomass processing technologies are more focused on obtaining high-quality pulp that is a raw material for the paper and packaging industry [102]. The resulting lignin is of a rather low quality, mostly due to the separation process [103]. The lists of common methods for lignin separation from liquors resulting from alkaline treatment of lignocellulosic biomass (pulping black liquor, alkaline extractive liquors) include pH reduction by acid addition (acidic precipitation), membrane filtration, and organic solvent precipitation [104,105]. The widest used method, acid precipitation, brings up advantages such as simplicity and cost effectiveness. Use of organic acids improves efficiency of lignin separation [105,106]. Regardless of the precipitation acid used, the obtained lignin, often referred to as raw lignin, contains a rather high number of polysaccharides that hinder the further valorization of lignin [107]. Recovery of sulfur-free lignin which is enabling new possibilities for utilization is possible by using soda pulping black liquors resulted most often resulting from agricultural residues pulping [108].

Table 5.

Chemical composition of raw lignin obtained from alkaline liquors after RS processing.

Table 6.

Chemical composition of raw lignin obtained from alkaline liquors after SS processing.

The purity of lignin samples isolated from AE liquors of RS and SS showed closed values of 37–39%. In terms of polysaccharide contamination, the situation looks different. The RS lignin showed a higher carbohydrate content than the lignin isolated from AE of SS. Pulping liquors yielded lignin having an acid-insoluble lignin content with about 30% purity in the case of RS SP and RS WT SP samples. In the case of SS SP and SS WT SP samples, the purity was of 34 and 37%, respectively. Both of these lignin samples had a carbohydrate content of about 7.6%. The carbohydrate content of the similar RS lignin is close to 10% carbohydrate content. The results on AE SP lignin samples for both RS and SS showed a purity of around 43%, although the carbohydrate content differed significantly.

The dominant carbohydrate found in raw lignin samples was shown to be xylan. In the case of the RS lignin samples, arabinan proved to be the second in the hierarchy, while in the SS lignin samples, the analytical results also showed arabinan as a second carbohydrate impurity, although lower content values were determined. Other contaminants in lignin samples are represented by salts or inorganic materials. As pointed out in the literature, the ash content of technical lignin may reach values as high as 20% [109].

Mussatto and coworkers showed the importance of the final pH value in lignin separation and recovery [110]. The authors point out that if the final pH of the precipitation stage is around 4.5, an optimal lignin recovery yield could be achieved, even though, at this stage, the lignin purity in terms of AIL is rather low and the carbohydrate content is high pointing out on the further need of purification. The values mentioned in the study are comparable to our data (40–50% AIL content in solids).

The resulting lignin purity values were difficult to compare with the literature data due to the variety of black liquor sources and lignin separation procedures. In fact, most of the studies concern the purification of either kraft or soda pulping lignin. Industrial separation of technical lignin is mostly performed by combined acid precipitation processes, such as LignoBoost and LignoForce [111]. The resulting products available as a commercial lignin still contain about 3–5% carbohydrates [112].

Under these circumstances, we mention several works for comparative purposes. Most of the studies used stages of acid washing at different temperatures to resolve the carbohydrate removal. Ruwoldt and coworkers obtained raw soda lignin from spruce and straw, with an initial acid-insoluble content ranging around 70% [113]. The authors of the study mention that an acid washing stage that also ensures the complete hydrolysis of carbohydrates is of particular importance.

Other studies, such as the work of Fang and coworkers, showed that raw lignin obtained by acid separation from kraft pulping black liquor of softwood contained about 3.5% carbohydrates [114]. Jablonsky and coworkers showed that acid-precipitated lignin from various non-wood sources such as flax and hemp had a purity of 80–87% dependent on the source and acid concentrations. The recovered yield of pure lignin ranged from 8 to 9 g/100 mL of black liquor [115].

3.5. Papermaking Properties of the Obtained Fibers

As previously mentioned, a first direction of solids resulting from the pulping procedure is the papermaking process. Table 7 depicts the most important mechanical properties of paper sheets obtained from the pulping of the studied raw materials. From Table 7 data, it is observable that the tensile strength index values (TSI) of the obtained laboratory paper sheets are comparable. In the case of the RS, the soda pulping alone resulted in the lowest value of tensile index values. The situation looked similar for the burst index. In the case of SS, similar magnitude values were obtained. In general, the use of preliminary extractive treatments proved beneficial for both of RS and SS. According to some authors, the strength property values fit the need for producing fluting packaging paper or hygiene paper [116,117,118].

Table 7.

Properties of RS and SS paper sheets.

When comparing the values of the TSI with literature data reports, we find that the values obtained for RS pulps are close to those reported by Potucek and coworkers [119] for soda pulps. The same authors showed that using soda–AQ pulping could lead to higher mechanical strength papers. The study mentions TSI values ranging from 4 to 6.4 N·m/g. In another study, of the same authors’ chemical-mechanical pulping of RS is taken into consideration. The values obtained for soda pulps were higher than those obtained for chemical-mechanical pulps that ranged 2–3.0 N·m/g [120].

Other studies concerning the pulping of RS reported higher values of TSI and BSI than the values mentioned in Table 7. Under the conditions of pulping mentioned by Mazhari Mousavi and coworkers, a 20% NaOH alkali charge and 40 min at 185 °C led to RS pulps for which the TSI and BSI values were higher than in the present study with 68.4 N·m/g and 3.42 kPa·m2/g [3]. The yield reported value for this pulp was of 35% which is considerably lower than the current study.

The SS pulp strength values seemed to also be similar to the reported literature values. TSI values of 35–42 N·m/g ans BSI of 1.75–2.2 kPa·m2/g were reported by Rudi and coworkers for neutral sulfite pups from SS at yield values of 40–60% [117]. Similar value ranges were reported by Kristova et. al. for soda pulps of SS under various parameters of pulping process that led to yield ranges of 36–44% [51]. The values of TSI and BSI were comparable to those reported in the literature for pulps obtained from different raw non wood materials such as wheat straw corn stalk. In this respect, typical wheat straw pulps have a TSI of 28–60 N·m/g [42,116]. The BSI literature reported that the value ranges are wider for wheat straw pulps: 1.5–4 kPa·m2/g [118,121]. Higher values of TSI and BSI may be found for corn stalks soda pulps: 50–70 N·m/g and 2.5–3.6 kPa·m2/g [122].

4. Conclusions

This study indicates that rapeseed straw and sunflower stalks are viable feedstocks for an integrated, multi-output biorefinery using extractive pretreatments and soda pulping. Both biomasses were successfully separated into hemicelluloses, lignin, and cellulose-rich pulps under the same processing conditions; the most successful method was alkaline extraction followed by soda pulping. The total solid losses were 55% for rapeseed straw and 70% for sunflower stalks, suggesting that rapeseed straws are more resistant to chemical processing.

Xylan was the dominant hemicellulose in both biomasses, representing up to 45% of the recovered hemicellulose fractions. Acid-insoluble lignin has a purity of 37–39%, which rises to 43% when soda pulping and alkaline extraction are combined. The cellulose-rich pulps showed satisfactory papermaking performance, with tensile strength indices of 35–55 N·m/g and burst indices of 1.1–2.4 kPa·m2/g, meeting the requirements for hygiene and fluting packaging papers.

Overall, the combined comparative approach and functional evaluation of the produced pulps distinguish this work from previous single-feedstock or single-output studies. The quantitative results obtained provide useful benchmarks for the integrated valorization of oilseed agricultural leftovers and support their usage in sustainable fiber-based biorefinery.

Despite the encouraging outcome, validated by the literature data, several limitations remain. The technological quality of agricultural leftovers varies greatly, and laboratory-scale circumstances do not accurately reflect the industrial performance. Future work should focus on optimization of pretreatment severity to balance product yield, purity, and energy demand. For better RS and SS valorization, integration with current oilseed processing streams may be a viable option.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.P. and M.T.N.; methodology A.C.P.; software A.C.P.; validation, A.C.P. and C.D.B.; formal analysis A.C.P.; investigation AC.; resources, C.D.B.; data curation C.D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.P.; writing—review and editing A.C.P. and M.T.N.; visualization C.D.B.; supervision A.C.P.; project administration, A.C.P.; funding acquisition, A.C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tuck, G.; Glendining, M.J.; Smith, P.; House, J.I.; Wattenbach, M. The potential distribution of bioenergy crops in Europe under present and future climate. Biomass Bioenergy 2006, 30, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=515326 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Mazhari Mousavi, S.M.; Hosseini, S.Z.; Resalati, H.; Mahdavi, S.; Rasooly Garmaroody, E. Papermaking potential of rapeseed straw, a new agricultural-based fiber source. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Qian, C.; Zhang, X.; Zuo, Q. Optimal Planting Density Increases the Seed Yield by Improving Biomass Accumulation and Regulating the Canopy Structure in Rapeseed. Plants 2024, 13, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Trinh, H.K.; Tricoulet, L.; Ballas, S.; Labonne, L.; Geelen, D.; Evon, P. Biorefinery of sunflower by-products: Optimization of twin-screw extrusion for novel biostimulants. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geletukha, G.G.; Zheliezna, T. Prospects for Bioenergy Development in Ukraine: Roadmap until 2050. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2021, 22, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazil, O.A.V.; Vilanova-Neta, J.L.; Silva, N.O.; Vieira, I.M.M.; Lima, Á.S.; Ruzene, D.S.; Silva, D.P.; Figueiredo, R.T. Integral use of lignocellulosic residues from different sunflower accessions: Analysis of the production potential for biofuels. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negiş, H. Impacts of Maize and Sunflower Straw Implementations on Selected Physical and Mechanical Properties of Clay Soil. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2024, 55, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Aslam, Z.; Khaliq, A.; Zahir, Z. Sunflower residue incorporation suppresses weeds, enhances soil properties and seed yield of spring-planted mung bean. Planta Daninha 2018, 36, e018176393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Lou, H.; Wang, X.; Shao, D.; Tan, X.; Liu, M.; Gao, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; et al. Optimized straw incorporation depth can improve the nitrogen uptake and yield of rapeseed by promoting fine root development. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 250, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Q.; Kuai, J.; Zhao, L.; Hu, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhou, G. The effect of sowing depth and soil compaction on the growth and yield of rapeseed in rice straw returning field. Field Crops Res. 2017, 203, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusek, G.; Ozturk, H.H.; Akdemir, S. An assessment of energy use of different cultivation methods for sustainable rapeseed production. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2772–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Allameh, A. Soil properties and crop yield under different tillage methods for rapeseed cultivation in paddy fields. J. Agric. Sci. Serb. 2015, 60, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blamey, F.P.C.; Zollinger, R.K.; Schneiter, A.A. Sunflower Production and Culture. In Sunflower Technology and Production; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 595–670. [Google Scholar]

- Ntunka, M.G.; Khumalo, S.M.; Makhathini, T.P.; Mtsweni, S.; Tshibangu, M.M.; Bwapwa, J.K. Valorization of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Biofuel: A Systematic Review. ChemEngineering 2025, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Sun, Z.-F.; Zhang, C.-C.; Nan, J.; Ren, N.-Q.; Lee, D.-J.; Chen, C. Advances in pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for bioenergy production: Challenges and perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 343, 126123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, L.; Khoo, K.S.; Gupta, V.K.; Sharma, M.; Show, P.L.; Yap, P.-S. Exploitation of lignocellulosic-based biomass biorefinery: A critical review of renewable bioresource, sustainability and economic views. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 69, 108265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrysh, V.; Kalinichenko, A.; Pysarenko, P.; Samojlik, M. Sunflower Residues-Based Biorefinery: Circular Economy Indicators. Processes 2023, 11, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svärd, A.; Moriana, R.; Brännvall, E.; Edlund, U. Rapeseed Straw Biorefinery Process. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrin, A.; Balzan, A.; Astrup, T. Energy and environmental analysis of a rapeseed biorefinery conversion process. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2013, 3, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttha, R.; Venkatachalam, K.; Hanpakdeesakul, S.; Wongsa, J.; Parametthanuwat, T.; Srean, P.; Pakeechai, K.; Charoenphun, N. Exploring the Potential of Sunflowers: Agronomy, Applications, and Opportunities within Bio-Circular-Green Economy. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofanica, B.M.; Cappelletto, E.; Gavrilescu, D.; Mueller, K. Properties of Rapeseed (Brassica napus) Stalks Fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 2011, 8, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marechal, V.; Rigal, L. Characterization of by-products of sunflower culture—Commercial applications for stalks and heads. Ind. Crops Prod. 1999, 10, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagour, J.; Ahmed, M.N.; Bouzid, H.A.; Oubannin, S.; Bijla, L.; Ibourki, M.; Hajib, A.; Koubachi, J.; Harhar, H.; Gharby, S. Proximate Composition, Physicochemical, and Lipids Profiling and Elemental Profiling of Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) and Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) Grown in Morocco. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 3505943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, G.; Dimitrellos, G.; Beobide, A.S.; Vayenas, D.; Lyberatos, G. Chemical Pretreatment of Sunflower Straw Biomass: The Effect on Chemical Composition and Structural Changes. Waste Biomass Valorization 2015, 6, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, X.; Ouyang, S. Comparative Evaluation of Dilute Acid, Alkaline, and Deep Eutectic Solvent Pretreatments on Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Sunflower Stalk Bark. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 5774–5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monlau, F.; Barakat, A.; Steyer, J.P.; Carrere, H. Comparison of seven types of thermo-chemical pretreatments on the structural features and anaerobic digestion of sunflower stalks. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 120, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahim, M.; Boussetta, N.; Grimi, N.; Vorobiev, E.; Zieger-Devin, I.; Brosse, N. Pretreatment optimization from rapeseed straw and lignin characterization. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 95, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Riyakhuni, M.; Hashemi, S.S.; Denayer, J.F.M.; Aghbashlo, M.; Tabatabaei, M.; Karimi, K. Integrated biorefining of rapeseed straw for ethanol, biogas, and mycoprotein production. Fuel 2025, 382, 133751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svärd, A.; Brännvall, E.; Edlund, U. Rapeseed straw as a renewable source of hemicelluloses: Extraction, characterization and film formation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 133, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmaz, E. Comparison of properties of cellulose nanomaterials (CNMs) obtained from sunflower stalks. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2021, 55, 755–770. [Google Scholar]

- Kindzera, D.; Kochubei, V. Comparison of the Energy Properties of Sunflower Stalk Fibers for Solid Biofuel Production. J. Chem. 2025, 2025, 7990012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroušek, J. Pretreatment of sunflower stalks for biogas production. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2013, 15, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdikhani, H.; Torshizi, H.J.; Ghalehno, M.D. Deeper insight into the morphological features of sunflower stalk as Biorefining criteria for sustainable production. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2019, 34, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deykun, I.; Halysh, V.; Barbash, V. Rapeseed straw as an alternative for pulping and papermaking. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2018, 52, 833–839. [Google Scholar]

- Puițel, A.C.; Balan, C.D.; Ailiesei, G.-L.; Drăgoi, E.N.; Nechita, M.T. Integrated Hemicellulose Extraction and Papermaking Fiber Production from Agro-Waste Biomass. Polymers 2023, 15, 4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puițel, A.C.; Bălușescu, G.; Balan, C.D.; Nechita, M.T. The Potential Valorization of Corn Stalks by Alkaline Sequential Fractionation to Obtain Papermaking Fibers, Hemicelluloses, and Lignin—A Comprehensive Mass Balance Approach. Polymers 2024, 16, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puițel, A.C.; Bârjoveanu, G.; Balan, C.D.; Nechita, M.T. Medicago Sativa Stems—A Multi-Output Integrated Biorefinery Approach. Polymers 2025, 17, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puițel, A.C.; Suditu, G.D.; Danu, M.; Ailiesei, G.-L.; Nechita, M.T. An Experimental Study on the Hot Alkali Extraction of Xylan-Based Hemicelluloses from Wheat Straw and Corn Stalks and Optimization Methods. Polymers 2022, 14, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puițel, A.C.; Suditu, G.D.; Drăgoi, E.N.; Danu, M.; Ailiesei, G.-L.; Balan, C.D.; Chicet, D.-L.; Nechita, M.T. Optimization of Alkaline Extraction of Xylan-Based Hemicelluloses from Wheat Straws: Effects of Microwave, Ultrasound, and Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Polymers 2023, 15, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, F.; Wang, X.; Liao, G.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Jiao, Y. Rapeseed Variety Recognition Based on Hyperspectral Feature Fusion. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suopajärvi, T.; Ricci, P.; Karvonen, V.; Ottolina, G.; Liimatainen, H. Acidic and alkaline deep eutectic solvents in delignification and nanofibrillation of corn stalk, wheat straw, and rapeseed stem residues. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 145, 111956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pińkowska, H.; Wolak, P.; Oliveros, E. Production of xylose and glucose from rapeseed straw in subcritical water—Use of Doehlert design for optimizing the reaction conditions. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 58, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, L.; He, W.; Qi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Su, X.; Deng, M.; Wang, K. Characterize the physicochemical structure and enzymatic efficiency of agricultural residues exposed to γ-irradiation pretreatment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 150, 112228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaee, N.; Nikzad, M.; Battisti, R.; Araghi, A. Isolation of cellulose nanofibers from rapeseed straw via chlorine-free purification method and its application as reinforcing agent in carboxymethyl cellulose-based films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 251, 126405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, A.; Keshtiban, N.A.; Gelir, A.; Ozbek, N.; Haykiri-Acma, H.; Yaman, S. Rapeseed stalk-derived hierarchical porous carbon as electrode material for supercapacitors. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 226, 120616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-W.; Zhu, M.-Q.; Li, M.-F.; Wei, Q.; Sun, R.-C. Effects of hydrothermal treatment on enhancing enzymatic hydrolysis of rapeseed straw. Renew. Energy 2019, 134, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M.J.; Cara, C.; Ruiz, E.; Romero, I.; Moya, M.; Castro, E. Hydrothermal pre-treatment of rapeseed straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 2428–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yin, J.; Fan, B.; He, Y.-C.; Ma, C. Valorization of rapeseed straw through the enhancement of cellulose accessibility, lignin removal and xylan elimination using an n-alkyltrimethylammonium bromide-based deep eutectic solvent. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 301, 140151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Tang, W.; Li, L.; Huang, M.; Ma, C.; He, Y.-C. Enhancing enzymatic hydrolysis of waste sunflower straw by clean hydrothermal pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 383, 129236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khristova, P.; Gabir, S.; Bentcheva, S.; Dafalla, S. Soda-anthraquinone pulping of sunflower stalks. Ind. Crops Prod. 1998, 9, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, E.; Romero, I.; Moya, M.; Cara, C.; Vidal, J.D.; Castro, E. Dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment of sunflower stalks for sugar production. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 140, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sert, M.; Arslanoğlu, A.; Ballice, L. Conversion of sunflower stalk based cellulose to the valuable products using choline chloride based deep eutectic solvents. Renew. Energy 2018, 118, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, E.; Cara, C.; Manzanares, P.; Ballesteros, M.; Castro, E. Evaluation of steam explosion pre-treatment for enzymatic hydrolysis of sunflower stalks. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2008, 42, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, H.; Jin, C.; Gu, H.; Qiu, Z. Enhanced bioethanol production from Compositae plant stalks: Integrating dry acid pretreatment and fungal mediated biodetoxification. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 42, 101817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; He, D.; Hou, T.; Lu, M.; Mosier, N.S.; Han, L.; Xiao, W. Structure–property–degradability relationships of varisized lignocellulosic biomass induced by ball milling on enzymatic hydrolysis and alcoholysis. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2022, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, P.; Rocha, I.V.; Özkan, M.; Angelidaki, I. Alkaline peroxide pretreatment of rapeseed straw for enhancing bioethanol production by Same Vessel Saccharification and Co-Fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 104, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, M.J.; Cara, C.; Ruiz, E.; Pérez-Bonilla, M.; Castro, E. Hydrothermal pre-treatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of sunflower stalks. Fuel 2011, 90, 3225–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.W.; Zhu, M.Q.; Li, M.F.; Wang, J.Q.; Wei, Q.; Sun, R.C. Comprehensive evaluation of the liquid fraction during the hydrothermal treatment of rapeseed straw. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.-Y.; Zhao, B.-C.; Li, M.-F.; Liu, Q.-Y.; Sun, R.-C. Fractionation of rapeseed straw by hydrothermal/dilute acid pretreatment combined with alkali post-treatment for improving its enzymatic hydrolysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 225, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmakhany, A.D.; Kashaninejad, M.; Aalami, M.; Maghsoudlou, Y.; Khomieri, M.; Tabil, L.G. Enhanced biomass delignification and enzymatic saccharification of canola straw by steam-explosion pretreatment. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 1607–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rubia, M.D.; Jurado-Contreras, S.; Navas-Martos, F.J.; García-Ruiz, Á.; Morillas-Gutiérrez, F.; Moya, A.J.; Mateo, S.; Rodríguez-Liébana, J.A. Characterization of Cellulosic Pulps Isolated from Two Widespread Agricultural Wastes: Cotton and Sunflower Stalks. Polymers 2024, 16, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparrós, S.; Ariza, J.; López, F.; Nacimiento, J.A.; Garrote, G.; Jiménez, L. Hydrothermal treatment and ethanol pulping of sunflower stalks. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1368–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.-J.; Lee, E.-J.; Lee, J.-W. The pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis behaviors of lignocellulosic biomass (oak and larch) based on structural changes in its lignin-carbohydrate complex. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 210, 118110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svärd, A.; Brännvall, E.; Edlund, U. Rapeseed straw polymeric hemicelluloses obtained by extraction methods based on severity factor. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 95, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Qi, M.; Goff, H.D.; Cui, S.W. Polysaccharides from sunflower stalk pith: Chemical, structural and functional characterization. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 100, 105082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cheng, L.; Ma, X.; Zhou, X.; Xu, Y. Revalorization of sunflower stalk pith as feedstock for the coproduction of pectin and glucose using a two-step dilute acid pretreatment process. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez-Pardo, L.-M.; González-Córdoba, A.; López-Galan, J. Evaluation of different methods for efficient extraction of hemicelluloses leaves and tops of sugarcane. DYNA 2018, 85, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska-Chargot, M.; Pękala, P.; Myśliwiec, D.; Cieśla, J.; Pieczywek, P.M.; Siemińska-Kuczer, A.; Zdunek, A. A study of the properties of hemicelluloses adsorbed onto microfibrillar cellulose isolated from apple parenchyma. Food Chem. 2024, 430, 137116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutterer, C.; Fackler, K.; Schild, G.; Ibl, V.; Potthast, A. Xylan Localization on Pulp and Viscose Fiber Surfaces. BioResources 2017, 12, 5632–5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Córdoba, A.; Flórez-Pardo, L.-M.; López-Galan, J. Characterization of hemicelluloses from leaves and tops of the CC 8475, CC 8592, and V 7151 varieties of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.). DYNA 2019, 86, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagia, S.; Durkovic, J.; Lagana, R.; Kardošová, M.; Kačík, F.; Cernescu, A.; Schäfer, P.; Yoo, C.G.; Ragauskas, A. Nanoscale FTIR and Mechanical Mapping of Plant Cell Walls for Understanding Biomass Deconstruction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 3016–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Wang, L. Thermal Treatment of Poplar Hemicelluloses at 180 to 220 °C under Nitrogen Atmosphere. BioResources 2016, 12, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Zongwei, G.; Xu, F. High Purity and Low Molecular Weight Lignin Nano-Particles Extracted from Acid-Assisted MIBK Pretreatment. Polymers 2020, 12, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nada, A.M.A.; Fadly, M.; Dawy, M. Spectroscopic study of the molecular structure of a lignin-polymer system. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1992, 37, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C.-M.; Vasile, C.; Popescu, M.-C.; Singurel, G.; Popa, V.; Munteanu, B. Analytical methods for lignin characterization. II. Spectroscopic studies. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2006, 40, 597–621. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzari, L.; Domingos, E.; Silva, L.; Kuznetsov, A.; Romão, W.; Araujo, J. Kraft lignin and polyethylene terephthalate blends: Effect on thermal and mechanical properties. Polímeros 2019, 29, e2019055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaini, M.F.; Khairul, W.M.; Arshad, S.; Abdullah, M.; Zainuri, D.A.; Rahamathullah, R.; Rosli, M.I.; Abd Aziz, M.S.; Razak, I.A. The structure-property studies and mechanism of optical limiting action of methyl 4-((4-aminophenyl)ethynyl)benzoate crystal under continuous wave laser excitation. Opt. Mater. 2020, 107, 110087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, Y.A.; Shestakov, S.L.; Belesov, A.V.; Pikovskoi, I.I.; Kozhevnikov, A.Y. Comprehensive analysis of the chemical structure of lignin from raspberry stalks (Rubus idaeus L.). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 3814–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Xing, D.; Lia, J. FTIR Studies of the Changes in Wood Chemistry from Wood Forming Tissue under Inclined Treatment. Energy Procedia 2012, 16, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Boardman, C.R.; Cai, Z. Thermal stability of metal-lignin composites prepared by coprecipitation method. Thermochim. Acta 2020, 690, 178659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, D.; Xu, F.; Geng, Z.; Sun, R.; Jones, G.; Baird, M. Physicochemical characterization of extracted lignin from sweet sorghum stem. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 32, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, W.; Kalasinsky, V.F.; Schultz, T.P. Infrared study of lignin: Assignment of methoxyl CH bending and stretching bands. Holzforschung 1997, 51, 167–168. [Google Scholar]

- Sammons, R.J.; Harper, D.P.; Labbé, N.; Bozell, J.J.; Elder, T.; Rials, T.G. Characterization of organosolv lignins using thermal and FT-IR spectroscopic analysis. BioResources 2013, 8, 2752–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.-J.; Xiao, L.-P.; Deng, J.; Sun, R.-C. Isolation and Structural Characterization of Lignin Polymer from Dendrocalamus sinicus. BioEnergy Res. 2013, 6, 1212–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minu, K.; Jiby, K.K.; Kishore, V. Isolation and purification of lignin and silica from the black liquor generated during the production of bioethanol from rice straw. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 39, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.C.; McDonald, A.G. Chemical and thermal characterization of three industrial lignins and their corresponding lignin esters. BioResources 2010, 5, 990–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanto, S.; Intan, A.P.; Rianto, B.; Kusworo, T.D.; Pramudono, B.; Untoro, E.; Ratu, P. The effect of acid concentration (H2SO4) on the yield and functional group during lignin isolation of biomass waste pulp and paper industry. Reaktor 2019, 19, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faix, O. Classification of Lignins from Different Botanical Origins by FT-IR Spectroscopy. Holzforschung 1991, 45, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrão, D.R.; Sain, M.; Leão, A.L.; Sameni, J.; Jeng, R.; Jesus, J.P.F.d.; Monteiro, R.T.R. Fragmentation of lignin from organosolv black liquor by white rot fungi. BioResources 2015, 10, 1553–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, T.; Kait, C.; Thanapalan, M. A “Fourier Transformed Infrared” Compound Study of Lignin Recovered from a Formic Acid Process. Procedia Eng. 2016, 148, 1312–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Tran, M.H.; Lee, E.Y. Hydroxymethylation of technical lignins obtained from different pretreatments for preparation of high-performance rigid polyurethane foam. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2022, 80, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, A.; Santos, B.; Brasil, K.; Vieira, I.; Ramos, L.; Souza, R.; Silva, D.; Ruzene, D. A statistical approach for the valorization of hemicellulosic liquor from sunflower stalk in biosurfactant production. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 23269–23284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabetafika, H.; Brahim, B.; Blecker, C.; Paquot, M.; Wathelet, B. Comparative study of alkaline extraction process of hemicelluloses from pear pomace. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 61, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yang, G.; Chen, J.; He, M. The Characterization of Hemicellulose Extract from Corn Stalk with Stepwise Alkali Extraction. J. Korea Tech. Assoc. Pulp Pap. Ind. 2017, 49, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andérez Fernández, M.; Rissanen, J.; Pérez Nebreda, A.; Xu, C.; Willför, S.; García Serna, J.; Salmi, T.; Grénman, H. Hemicelluloses from stone pine, holm oak, and Norway spruce with subcritical water extraction − comparative study with characterization and kinetics. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 133, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.C.; Tomkinson, J. Characterization of hemicelluloses obtained by classical and ultrasonically assisted extractions from wheat straw. Carbohydr. Polym. 2002, 50, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriez, V.; Peydecastaing, J.; Pontalier, P.-Y. Lignocellulosic Biomass Mild Alkaline Fractionation and Resulting Extract Purification Processes: Conditions, Yields, and Purities. Clean Technol. 2020, 2, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariduraganavar, M.Y.; Kittur, A.A.; Kamble, R.R. Chapter 1—Polymer Synthesis and Processing. In Natural and Synthetic Biomedical Polymers; Kumbar, S.G., Laurencin, C.T., Deng, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, D.; Rana, V.; Sharma, S.; Kumar Walia, Y.; Kumar, K.; Umar, A.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Baskoutas, S. Hemicelluloses: A Review on Extraction and Modification for Various Applications. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e06050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marins-Gonçalves, L.; Hespanhol Miranda Reis, M. Lignin Recovery from Black Liquor. In Handbook of Lignin; Jawaid, M., Ahmad, A., Meraj, A., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025; pp. 1435–1459. [Google Scholar]

- Saadan, R.; Hachimi Alaoui, C.; Ihammi, A.; Chigr, M.; Fatimi, A. A Brief Overview of Lignin Extraction and Isolation Processes: From Lignocellulosic Biomass to Added-Value Biomaterials. Environ. Earth Sci. Proc. 2024, 31, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauwaert, J.; Stals, I.; Lancefield, C.S.; Deschaumes, W.; Depuydt, D.; Vanlerberghe, B.; Devlamynck, T.; Bruijnincx, P.C.A.; Verberckmoes, A. Pilot scale recovery of lignin from black liquor and advanced characterization of the final product. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 221, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, A.; Balakshin, M. Chapter 18—Industrial Lignins: Analysis, Properties, and Applications. In Bioenergy Research: Advances and Applications; Gupta, V.K., Tuohy, M.G., Kubicek, C.P., Saddler, J., Xu, F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 315–336. [Google Scholar]

- Arkell, A.; Olsson, J.; Wallberg, O. Process performance in lignin separation from softwood black liquor by membrane filtration. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2014, 92, 1792–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duret, E.; de Moura, L.C.R.; Morales, A.; Labidi, J.; Robles, E.; Charrier-El Bouhtoury, F. Efficient Lignin Precipitation from Softwood Black Liquor Using Organic Acids for Sustainable Valorization. Polymers 2025, 17, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, N.H.; Pham, H.H.; Le, T.M.; Lauwaert, J.; Diels, L.; Verberckmoes, A.; Do, N.H.N.; Tran, V.T.; Le, P.K. The novel method to reduce the silica content in lignin recovered from black liquor originating from rice straw. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossberg, C.; Bremer, M.; Machill, S.; Koenig, S.; Kerns, G.; Boeriu, C.; Windeisen, E.; Fischer, S. Separation and characterisation of sulphur-free lignin from different agricultural residues. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 73, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahvazi, B.; Cloutier, É.; Wojciechowicz, O.; Ngo, T.-D. Lignin Profiling: A Guide for Selecting Appropriate Lignins as Precursors in Biomaterials Development. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 5090–5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussatto, S.I.; Fernandes, M.; Roberto, I.C. Lignin recovery from brewer’s spent grain black liquor. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 70, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulos, D.; Crestini, C.; Dahlstrand, C.; Furusjö, E.; Gioia, C.; Jedvert, K.; Henriksson, G.; Hulteberg, C.; Lawoko, M.; Pierrou, C.; et al. Kraft Lignin: A Valuable, Sustainable Resource, Opportunities and Challenges. ChemSusChem 2023, 16, e202300492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, D.; Langis-Barsetti, S.; Gagné, A.; Palus, E.; Inwood, J.; Konduri, M.K.R. Aqueous ethanol fractionation of softwood and hardwood kraft lignins: Impact on purity and properties. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2024, 44, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwoldt, J.; Syverud, K.; Tanase-Opedal, M. Purification of soda lignin. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2024, 6, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Ståhl, M.; Ershova, O.; Heikkinen, S.; Sixta, H. Purification and characterization of kraft lignin. Holzforschung 2015, 69, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonsky, M.; Šurina, I.; Haz, A.; Sládková, A.; Briškárová, A.; Kačík, F.; Šíma, J. Characterization of Non-wood Lignin Precipitated with Sulphuric Acid of Various Concentrations. Bioresources 2015, 10, 1408–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Urdaneta, F.; Kumar, R.; Marquez, R.; Vera, R.E.; Franco, J.; Urdaneta, I.; Saloni, D.; Venditti, R.A.; Pawlak, J.J.; Jameel, H.; et al. Evaluating chemi-mechanical pulping processes of agricultural residues: High-yield pulps from wheat straw for fiber-based bioproducts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 221, 119379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudi, H.; Resalati, H.; Eshkiki, R.B.; Kermanian, H. Sunflower stalk neutral sulfite semi-chemical pulp: An alternative fiber source for production of fluting paper. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 127, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagel, S.; Schütt, F. Reinforcement Fiber Production from Wheat Straw for Wastepaper-Based Packaging Using Steam Refining with Sodium Carbonate. Clean Technol. 2024, 6, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potucek, F.; Gurung, B.; Hájková, K. Soda pulping of rapeseed straw. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2014, 48, 683–691. [Google Scholar]

- Potucek, F.; Říhová, M.; Gurung, B. Chemi-mechanical pulp from rapeseed Straw. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2016, 50, 489–496. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, F.; Kordsachia, T.; Heizmann, T.; Eckardt, M.P.; Chen, Y.; Saake, B. Sodium Carbonate Pulping of Wheat Straw—An Alternative Fiber Source for Various Paper Applications. Agronomy 2024, 14, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, T.; Quaiyyum, M.A.; Salam, A.; Jahan, M.S. Pulping of bagasse (Saccrarum officinarum), kash (Saccharum spontaneum) and corn stalks (Zea mays). Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 3, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.