Polymeric Biocoatings for Postharvest Fruit Preservation: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Search Methodology

3. Properties of Biocoatings

3.1. Materials Key in Biocoatings

3.2. Physico-Mechanical and Barrier Properties

3.2.1. Mechanical Properties

3.2.2. Water Vapor Permeability

3.2.3. Solubility

3.2.4. Viscosity

3.2.5. Adhesion and Coverage

3.3. Functional Properties

3.3.1. Antimicrobial Activity

3.3.2. Antifungal Activity

3.3.3. Emulsifying Properties

3.3.4. Sensory and Optical Properties

| Properties | Raw Material/System | Typical Range and Units | Measurement Method and Conditions | Main Results | Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical properties | Soy protein + epoxidized castor oil Starch + chitosan | TS: 5–25 MPa, EB: 10–40% | ASTM D882-16; 25 °C; 50% RH; crosshead speed 10 mm/min | ↑ elongation at break (23%) ↑ mechanical strength and cohesion | Fresh fruits, tomatoes, apples | [39,45,79] |

| Water vapor permeability | Sodium caseinate + beeswax Starch + gluten + carnauba wax | 0.5–4.0 × 10−9 g·m/(m2·s·Pa) | ASTM E96/E96M-16; 25 °C; 75% RH | ↓ permeability, improved moisture retention. Greater stability against moisture | Grapes, strawberries, mango, papaya | [40,41,80] |

| Antimicrobial | Chitosan + olive oil Gelatin | Inhibition zones: 8–20 mm; Log-reduction: 1–4 log CFU | Disk diffusion; plate count method; 25 °C | Antimicrobial activity like gentamicin. Intrinsic antibacterial activity | Strawberries, blueberries, among various fruits | [34,57] |

| Antifungal | Chitosan + oregano essential oil | Mycelial inhibition: 60–100% | PDA culture, storage at 4–20 °C; relative humidity 80–90% | Inhibits Botrytis cinerea | Grapes, blueberries | [81,82] |

| Optical | Tea extract (polyphenols) Natural antioxidants | Light transmission (600 nm): 20–60%; ΔE color: 3–10 | UV–Vis spectrophotometry; CIEXYZ colorimetry | Green-yellow pigmentation, UV protection. UV blocking, ↓ oxidation | Direct coating, blueberries, cherries | [72,76] |

| Antioxidants | Chitosan + rosemary extract | DPPH inhibition: 40–80%; ORAC: 500–1200 µmol TE/g | DPPH, ABTS, ORAC assays; 25 °C | ↓ lipid oxidation, ↑ phenolic stability | Avocado | [83,84,85] |

| Solubility | Breadfruit starch Starch + chitosan | 8–36% (w/w) | 25 °C; 24 h hydration; gravimetric analysis | ↓ solubility (36% to 8%) Better stability in moisture | Papaya, strawberries, grapes | [39,48,86] |

| Viscosity | 1% chitosan solutions | 60–120 mPa·s | Brookfield viscometer; spindle 2; 25 °C | 86 mPa·s; better coverage | Tomatoes, pears | [33] |

| Emulsification | Pickering with nanocellulose. Nanoemulsions with essential oils | Droplet size: 50–300 nm; EAI: 20–50 m2/g | Dynamic light scattering (DLS); turbidimetry | Excellent stability without surfactants. ↓ droplet size, ↑ bioavailability | Mangoes, kiwis, strawberries | [67,68] |

| Adhesion/coverage | Chitosan + glycerol | Adhesion rating: high (qualitative); thickness 20–60 μm | Visual analysis; cross-section SEM | Uniform coverage and high adhesion to skin | Apples, peaches | [87] |

| Enzymatic activity | Alginate + green tea extract | PPO/LOX inhibition: 20–60% | PPO/LOX assays; 4–10 °C | Inhibits polyphenol oxidase, ↓ browning | Avocados, pears, strawberries | [88,89] |

| Biodegradability | Starch films + PLA | Complete degradation: <90 days | Composting test (ISO 14855-1:2012) | Compostable in <90 days | Coating and packaging | [90,91] |

4. Natural Polymers Used in Biocoatings

5. Methods of Applying Biocoatings to Fruit

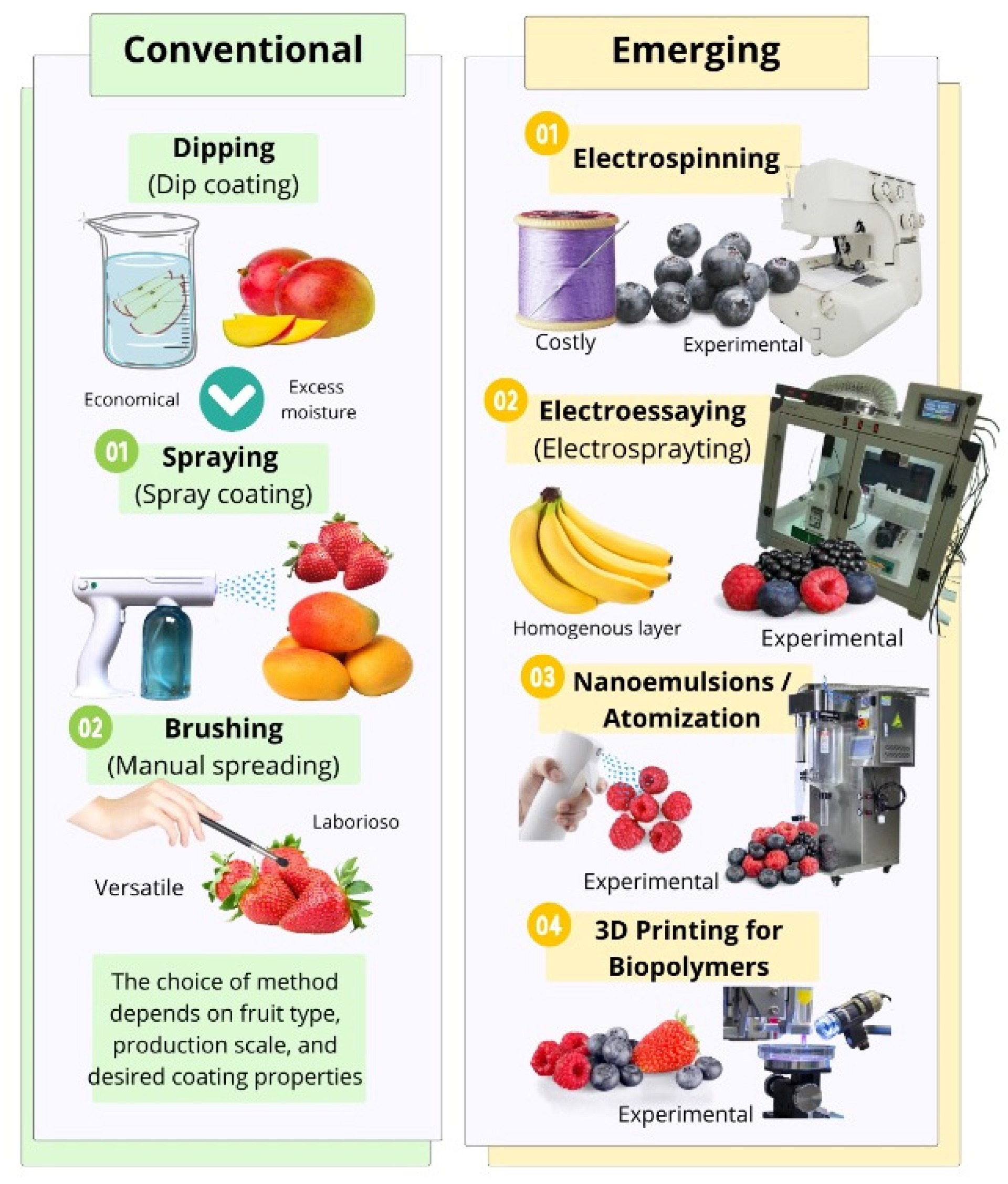

5.1. Conventional Methods

5.2. Emerging Methods

5.3. Selection Criteria by Fruit Type and TRLs

6. Regulatory Section and Industrialization

7. Incorporation of Bioactive Compounds

8. Reinforced Quantitative Examples and Sensory Implications

9. Future Prospects

10. Conclusions

- I.

- Polymeric biocoatings show strong potential to extend the shelf life of fresh fruits by integrating natural polymers with antimicrobial, antioxidant, and barrier-active compounds.

- II.

- The performance of these systems depends heavily on polymer type, formulation strategy, and application method, which determines coating uniformity, controlled release, and overall fruit quality.

- III.

- Emerging approaches, including nanoemulsions, nanocellulose-based systems, and electrohydrodynamic technologies, offer promising functional advantages but still require optimization for industrial scalability.

- IV.

- Standardizing postharvest evaluation protocols under realistic storage, distribution, and retail conditions is essential to ensure comparable datasets and accelerate technological adoption.

- V.

- Developing scalable controlled-release systems (such as nanoemulsions or polymer–phenolic complexes) remains a priority to maintain stability, reduce the required load of active compounds, and preserve sensory quality.

- VI.

- Advancing the use of circular economy inputs such as phenolics, essential oils, and polysaccharides extracted from agro-industrial by-products through green and low-energy extraction techniques will be critical for reducing formulation costs and strengthening sustainability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Agricultural Production Statistics 2000–2020; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2022; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Agricultural Production Statistics 2010–2023; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2024; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Perumal, A.B.; Huang, L.; Nambiar, R.B.; He, Y.; Li, X.; Sellamuthu, P.S. Application of Essential Oils in Packaging Films for the Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. Food Chem. 2022, 375, 131810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, V.F.R.; Pintado, M.E.; Morais, R.M.S.C.; Morais, A.M.M.B. Recent Highlights in Sustainable Bio-Based Edible Films and Coatings for Fruit and Vegetable Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Wang, X.; Mao, X.; He, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y. Recent Advances in Starch-Based Coatings for the Postharvest Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 328, 121736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieu, M.D.; Phuong, T.V.; Nguyen, T.T.B.; Dang, T.K.T.; Nguyen, T.H. A Review of Preservation Approaches for Extending Avocado Fruit Shelf-Life. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Nguyen, L.L.P.; Dam, M.S.; Baranyai, L. Application of Edible Coating in Extension of Fruit Shelf Life: Review. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Wang, Z.; Bu, J.; Fan, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Jiang, F. Konjac Glucomannan-Based Nanocomposite Spray Coating with Antimicrobial, Gas Barrier, UV Blocking, and Antioxidation for Bananas Preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 265, 130895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, C.-Q.; Kang, X.; Zeng, K. Preparation of Water-Soluble Dialdehyde Cellulose Enhanced Chitosan Coating and Its Application on the Preservation of Mandarin Fruit. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 203, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Duarte, G.; Pérez-Cabrera, L.E.; Artés-Hernández, F.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Ag-Chitosan Nanocomposites in Edible Coatings Affect the Quality of Fresh-Cut Melon. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 147, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, S.S.; Pradhan, K.C. A Review on Antimicrobial Nano-Based Edible Packaging: Sustainable Applications and Emerging Trends in Food Industry. Food Control 2024, 163, 110470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuvaraj, D.; Iyyappan, J.; Gnanasekaran, R.; Ishwarya, G.; Harshini, R.P.; Dhithya, V.; Chandran, M.; Kanishka, V.; Gomathi, K. Advances in Bio Food Packaging—An Overview. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabpoor, B.; Yousefi, S.; Weisany, W.; Ghasemlou, M. Multifunctional Coating Composed of Eryngium campestre L. Essential Oil Encapsulated in Nano-Chitosan to Prolong the Shelf-Life of Fresh Cherry Fruits. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 111, 106394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, H.; Licciardello, F.; Fava, P.; Siesler, H.W.; Pulvirenti, A. Recent Advances on Chitosan-Based Films for Sustainable Food Packaging Applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 26, 100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, P.S.U.; Adhika, D.R.; Genecya, G.; Al Madanie, M.S.; Asri, L.A.T.W. Evaluación de La Nanoemulsión de Aceite Esencial de Limoncillo (Cymbopogon citratus) Encapsulada En Quitosano Para El Recubrimiento Comestible de Frutas. OpenNano 2025, 24, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahirad, S.; Dadpour, M.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Soltanzadeh, M.; Gullón, B.; Alirezalu, K.; Lorenzo, J.M. Applications of Carboxymethyl Cellulose- and Pectin-Based Active Edible Coatings in Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Jiao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Lv, Z.; Yang, W.; Chen, D.; Liu, H. Polysaccharide-Based Packaging Coatings and Films with Phenolic Compounds in Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables—A Review. Foods 2024, 13, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, T.; Biswas, D.; Rhim, J.-W. Antimicrobial Nanofillers Reinforced Biopolymer Composite Films for Active Food Packaging Applications—A Review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2022, 32, e00353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, M.; Ruan, C.-Q. The Reduce of Water Vapor Permeability of Polysaccharide-Based Films in Food Packaging: A Comprehensive Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 321, 121267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurić, S.; Bureš, M.S.; Vlahoviček-Kahlina, K.; Stracenski, K.S.; Fruk, G.; Jalšenjak, N.; Bandić, L.M. Chitosan-Based Layer-by-Layer Edible Coatings Application for the Preservation of Mandarin Fruit Bioactive Compounds and Organic Acids. Food Chem. X 2023, 17, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.-X.; He, Z.; Sun, Q.; He, Q.; Zeng, W.-C. A Functional Polysaccharide Film Forming by Pectin, Chitosan, and Tea Polyphenols. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 215, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alara, O.R.; Abdurahman, N.H.; Ukaegbu, C.I. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds: A Review. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Gao, H.-X.; He, Q.; Zeng, W.-C. Potential Application of Phenolic Compounds with Different Structural Complexity in Maize Starch-Based Film. Food Struct. 2023, 36, 100318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.R.S.; Eapen, A.S.; Zhang, W.; Roy, S. Polysaccharide-Based Edible Biopolymer-Based Coatings for Fruit Preservation: A Review. Foods 2024, 13, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Nath, P.C.; Das, P.; Rustagi, S.; Sharma, M.; Sridhar, N.; Hazarika, T.K.; Rana, P.; Nayak, P.K.; Sridhar, K. Essential Oil-Nanoemulsion Based Edible Coating: Innovative Sustainable Preservation Method for Fresh/Fresh-Cut Fruits and Vegetables. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Huang, Y.; Yang, W.; Ling, Z.; Liu, S.; Zheng, S.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Pan, L.; Fan, W.; et al. Emerging Nanocellulose from Agricultural Waste: Recent Advances in Preparation and Applications in Biobased Food Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselice, A.; Colantuoni, F.; Lass, D.A.; Nardone, G.; Stasi, A. Trends in EU Consumers’ Attitude towards Fresh-Cut Fruit and Vegetables. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 59, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesías, F.J.; Martín, A.; Hernández, A. Consumers’ Growing Appetite for Natural Foods: Perceptions towards the Use of Natural Preservatives in Fresh Fruit. Food Res. Int. 2021, 150, 110749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Estevinho, B.N.; Rocha, F. Preparation and Incorporation of Functional Ingredients in Edible Films and Coatings. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2021, 14, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.A.; El-Sakhawy, M.; El-Sakhawy, M.A.-M. Polysaccharides, Protein and Lipid -Based Natural Edible Films in Food Packaging: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 238, 116178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Kumar, N.; Upadhyay, A.; Pratibha; Anurag, R.K. Edible Packaging from Fruit Processing Waste: A Comprehensive Review. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 2075–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanga-Labayen, J.P.; Yuan, Q. Making Biodegradable Seedling Pots from Textile and Paper Waste—Part A: Factors Affecting Tensile Strength. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, K.; Thirunavookarasu, N.; Chidanand, D.V. Recent Advances in Edible Coating of Food Products and Its Legislations: A Review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 12, 100623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Gogoi, J.; Dubey, S.; Chowdhury, D. Animal Derived Biopolymers for Food Packaging Applications: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 255, 128197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirozzi, A.; Del Grosso, V.; Ferrari, G.; Donsì, F. Edible Coatings Containing Oregano Essential Oil Nanoemulsion for Improving Postharvest Quality and Shelf Life of Tomatoes. Foods 2020, 9, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabot, G.L.; Schaefer Rodrigues, F.; Polano Ody, L.; Vinícius Tres, M.; Herrera, E.; Palacin, H.; Córdova-Ramos, J.S.; Best, I.; Olivera-Montenegro, L. Encapsulation of Bioactive Compounds for Food and Agricultural Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordevic, S.; Dordevic, D.; Sedlacek, P.; Kalina, M.; Tesikova, K.; Antonic, B.; Tremlova, B.; Treml, J.; Nejezchlebova, M.; Vapenka, L.; et al. Incorporation of Natural Blueberry, Red Grapes and Parsley Extract By-Products into the Production of Chitosan Edible Films. Polymers 2021, 13, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Tebar, N.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J.; Viuda-Martos, M. Chitosan Edible Films and Coatings with Added Bioactive Compounds: Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties and Their Application to Food Products: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremenkamp, I.; Sousa-Gallagher, M.J. Design and Development of an Edible Coating for a Ready-to-Eat Fish Product. Polymers 2024, 16, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Filho, J.G.; Albiero, B.R.; Cipriano, L.; de Oliveira Nobre Bezerra, C.C.; Oldoni, F.C.A.; Egea, M.B.; de Azeredo, H.M.C.; Ferreira, M.D. Arrowroot Starch-Based Films Incorporated with a Carnauba Wax Nanoemulsion, Cellulose Nanocrystals, and Essential Oils: A New Functional Material for Food Packaging Applications. Cellulose 2021, 28, 6499–6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, C.; Tihan, G.; Zgârian, R.; Pandelea (Voicu), G. Bio-Coatings for Preservation of Fresh Fruits and Vegetables. Coatings 2023, 13, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, K.; Cui, M.; Chen, D.; Guan, D.; Luan, G.; Xu, H. Development and Evaluation of Gum Arabic-Based Antioxidant Nanocomposite Films Incorporated with Cellulose Nanocrystals and Fruit Peel Extracts. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 30, 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzzadeh, S.; Akhavan, H.-R.; Khorasani, S.; Hajimohammadi-Farimani, R.; Alizadeh-Bahaabadi, G. Effect of Cinnamaldehyde-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers in Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Based Coating on the Shelf Life of Fresh Pistachio. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 350, 114299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi Dehbakri, S.; Ehtesham Nia, A.; Mumivand, H.; Rastegar, S. Effect of Nanocellulose-Based Edible Coatings Enriched with α-Pinene and Myrtle Essential Oil on the Postharvest Quality of Strawberry. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Shi, J. Preparation and Characterization of All-Biomass Soy Protein Isolate-Based Films Enhanced by Epoxy Castor Oil Acid Sodium and Hydroxypropyl Cellulose. Materials 2016, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culqui-Arce, C.; Mori-Mestanza, D.; Fernández-Jeri, A.B.; Cruzalegui, R.J.; Mori Zabarburú, R.C.; Vergara, A.J.; Cayo-Colca, I.S.; da Silva, J.G.; Araujo, N.M.P.; Castro-Alayo, E.M.; et al. Polymers Derived from Agro-Industrial Waste in the Development of Bioactive Films in Food. Polymers 2025, 17, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Md Nor, S.; Ding, P. Trends and Advances in Edible Biopolymer Coating for Tropical Fruit: A Review. Food Res. Int. 2020, 134, 109208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liyanapathiranage, A.; Dassanayake, R.S.; Gamage, A.; Karri, R.R.; Manamperi, A.; Evon, P.; Jayakodi, Y.; Madhujith, T.; Merah, O. Recent Developments in Edible Films and Coatings for Fruits and Vegetables. Coatings 2023, 13, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, L.S.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Lipid Incorporated Biopolymer Based Edible Films and Coatings in Food Packaging: A Review. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 8, 100720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sruthimol, J.J.; Haritha, K.; Warrier, A.S.; Lal, A.M.N.; Harikrishnan, M.P.; Rahul, C.J.; Kothakota, A. Tailoring the Properties of Natural Fibre Biocomposite Using Chitosan and Silk Fibroin Coatings for Eco-Friendly Packaging. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 225, 120465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurzyńska, A.; Janowicz, M.; Karwacka, M.; Nowacka, M.; Galus, S. Development and Characteristics of Protein Edible Film Derived from Pork Gelatin and Beef Broth. Polymers 2024, 16, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Vázquez, S.E.; Dublán-García, O.; Arizmendi-Cotero, D.; Gómez-Oliván, L.M.; Islas-Flores, H.; Hernández-Navarro, M.D.; Ramírez-Durán, N. Optimization of the Physical, Optical and Mechanical Properties of Composite Edible Films of Gelatin, Whey Protein and Chitosan. Molecules 2022, 27, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.; Marcet, I.; Rendueles, M.; Díaz, M. Edible Films from the Laboratory to Industry: A Review of the Different Production Methods. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 3245–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aayush, K.; McClements, D.J.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, R.; Singh, G.P.; Sharma, K.; Oberoi, K. Innovations in the Development and Application of Edible Coatings for Fresh and Minimally Processed Apple. Food Control 2022, 141, 109188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, B.; Duraisamy, R.; Birhanu, T. Study on the Preparation and Use of Edible Coating of Fish Scale Chitosan and Glycerol Blended Banana Pseudostem Starch for the Preservation of Apples, Mangoes, and Strawberries. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 100916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, E.; Nematollahi, A.; Hosseini, H. Composition of Antimicrobial Edible Films and Methods for Assessing Their Antimicrobial Activity: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyuz, L.; Kaya, M.; Ilk, S.; Cakmak, Y.S.; Salaberria, A.M.; Labidi, J.; Yılmaz, B.A.; Sargin, I. Effect of Different Animal Fat and Plant Oil Additives on Physicochemical, Mechanical, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties of Chitosan Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapi’i, R.A.; Othman, S.H.; Nordin, N.; Kadir Basha, R.; Nazli Naim, M. Antimicrobial Properties of Starch Films Incorporated with Chitosan Nanoparticles: In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 230, 115602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremenkamp, I.; Sousa Gallagher, M.J. Edible Coatings for Ready-to-Eat Products: Critical Review of Recent Studies, Sustainable Packaging Perspectives, Challenges and Emerging Trends. Polymers 2025, 17, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés, A.; Ramos, M.; Beltrán, A.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigós, M.C. State of the Art of Antimicrobial Edible Coatings for Food Packaging Applications. Coatings 2017, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yang, H.; Lu, X.; Wu, Y.; Blasi, F. The Inhibitory Effect of Chitosan Based Films, Incorporated with Essential Oil of Perilla Frutescens Leaves, against Botrytis Cinerea during the Storage of Strawberries. Processes 2022, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.M.; Mosa, M.A.; El-Ganainy, S.M. Chitosan-Decorated Copper Oxide Nanocomposite: Investigation of Its Antifungal Activity against Tomato Gray Mold Caused by Botrytis Cinerea. Polymers 2023, 15, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, K.; de Oliveira, A.G.; Tischer, C.A.; Hussain, I.; Roberto, S.R. Synergistic Effect of a Novel Chitosan/Silica Nanocomposites-Based Formulation against Gray Mold of Table Grapes and Its Possible Mode of Action. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 141, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Santiago, V.; Miranda, M.; Aguiló-Aguayo, I.; Teixidó, N.; Ortiz-Solà, J.; Abadias, M. Antimicrobial Efficacy of Nanochitosan and Chitosan Edible Coatings: Application for Enhancing the Safety of Fresh-Cut Nectarines. Coatings 2025, 15, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Pei, J.; Xiong, X.; Xue, F. Encapsulation of Grapefruit Essential Oil in Emulsion-Based Edible Film Prepared by Plum (Pruni Domesticae Semen) Seed Protein Isolate and Gum Acacia Conjugates. Coatings 2020, 10, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, A.; Kumar, V.; Dhiman, A.; Thakur, P.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, S. Nanoemulsion Based Edible Coatings for Quality Retention of Fruits and Vegetables-Decoding the Basics and Advancements in Last Decade. Environ. Res. 2024, 240, 117450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Vazquez, A.; Barciela, P.; Carpena, M.; Prieto, M.A. Edible Coatings as a Natural Packaging System to Improve Fruit and Vegetable Shelf Life and Quality. Foods 2023, 12, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Guan, W.; Zhou, X.; Lao, M.; Cai, L. The Physiochemical and Preservation Properties of Anthocyanidin/Chitosan Nanocomposite-Based Edible Films Containing Cinnamon-Perilla Essential Oil Pickering Nanoemulsions. LWT 2022, 153, 112506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Xia, W.; Xiong, Y.L.; Wang, H. Enhanced Physicochemical Properties of Chitosan/Whey Protein Isolate Composite Film by Sodium Laurate-Modified TiO2 Nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 138, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Zuo, G.; Chen, F. Effect of Essential Oil and Surfactant on the Physical and Antimicrobial Properties of Corn and Wheat Starch Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 1302–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Gu, M.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, Y. Effect of Tea Polyphenols on Chitosan Packaging for Food Preservation: Physicochemical Properties, Bioactivity, and Nutrition. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, W. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Chitosan Film with Tea Polyphenols-Mediated Green Synthesis Silver Nanoparticle via a Novel One-Pot Method. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereda, M.; Dufresne, A.; Aranguren, M.I.; Marcovich, N.E. Polyelectrolyte Films Based on Chitosan/Olive Oil and Reinforced with Cellulose Nanocrystals. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros, L.F.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Teixeira, J.A.; Mussatto, S.I. Production and Physicochemical Properties of Carboxymethyl Cellulose Films Enriched with Spent Coffee Grounds Polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Pei, J.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xue, F.; Xiong, X.; Li, C. Enhancing Physiochemical Properties of Chitosan Films Through Photo-Crosslinking by Riboflavin. Fibers Polym. 2022, 23, 2707–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Tavassoli, M.; Mohammadian, E.; Ehsani, A.; Khaniki, G.J.; Priyadarshi, R.; Rhim, J.-W. pH-Responsive Color Indicator Films Based on Methylcellulose/Chitosan Nanofiber and Barberry Anthocyanins for Real-Time Monitoring of Meat Freshness. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 166, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, H.; Liu, J.; Qin, Y.; Bai, R.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J. Antioxidant and pH-Sensitive Films Developed by Incorporating Purple and Black Rice Extracts into Chitosan Matrix. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 137, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Yang, G.; Janaswamy, S.; Xu, F.; Liu, Z. Preparation and Characterization of Lignin Nanoparticles and Chitin Nanofibers Reinforced PVA Films with UV Shielding Properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 188, 115669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D882-16; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM E96/E96M-16; Standard Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Grande-Tovar, C.D.; Chaves-Lopez, C.; Serio, A.; Rossi, C.; Paparella, A. Chitosan Coatings Enriched with Essential Oils: Effects on Fungi Involved in Fruit Decay and Mechanisms of Action. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulawik, P.; Tadesse, E.E.; Guzik, P.; Tkaczewska, J.; Zając, M.; Janik, M.; Tadele, W.; Grzebieniarz, W.; Nowak, N.; Szymkowiak, A.; et al. Effects of Triple-Layer Chitosan/Furcellaran Mini-/Nanoemulsions with Oregano Essential Oil and LL37 Bioactive Peptide on Shelf-Life of Cold/Frozen Stored Pork Loin. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 159, 110713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Liu, C.; Unsalan, O.; Altunayar-Unsalan, C.; Xiong, S.; Manyande, A.; Chen, H. Development and Characterization of Fish Myofibrillar Protein/Chitosan/Rosemary Extract Composite Edible Films and the Improvement of Lipid Oxidation Stability during the Grass Carp Fillets Storage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 184, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, R. Chitosan Nanoemulsions as Advanced Edible Coatings for Fruits and Vegetables: Composition, Fabrication and Developments in Last Decade. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 152, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastaniah, S.D. Uso de Películas de Nisina-Quitosano Enriquecidas Con Extracto de Romero En Listeria innocua, Escherichia coli O157:H7 y Pseudomonas aeruginosa En Salmón Ahumado En Frío Durante El Almacenamiento En Frío. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14855:2018; Plastics—Determination of the Ultimate Aerobic Biodegradability of Plastic Materials under Controlled Composting Conditions—Method by Analysis of Evolved Carbon Dioxide. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Subramani, G.; Manian, R. Bioactive Chitosan Films: Integrating Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Antifungal Properties in Food Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metha, C.; Pawar, S.; Suvarna, V. Recent Advancements in Alginate-Based Films for Active Food Packaging Applications. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1246–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Q.; Tang, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, Q.; Wu, C.; Pang, J. Development and Characterization of Alginate/Konjac Glucomannan Composite Film Reinforced with Propolis Extract and Tea Tree Essential Oil Co-Loaded Pickering Emulsions for Strawberry Preservation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 235, 121669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.C.; Sharma, R.; Debnath, S.; Sharma, M.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Dikkala, P.K.; Nayak, P.K.; Sridhar, K. Recent Trends in Polysaccharide-Based Biodegradable Polymers for Smart Food Packaging Industry. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Debbarma, R.; Habibi, M.; Haque, S.; Suprasanna, P. Banana Waste Valorisation and the Development of Biodegradable Biofilms. Waste Manag. Bull. 2025, 3, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, Z.; Shi, J.; Zou, X.; Zhai, X.; Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Holmes, M.; Daglia, M.; Xiao, J. Physical Properties and Bioactivities of Chitosan/Gelatin-Based Films Loaded with Tannic Acid and Its Application on the Preservation of Fresh-Cut Apples. LWT 2021, 144, 111223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.; Simonin, S.; Bach, B. Applications of Chitosan in the Agri-Food Sector: A Review. Carbohydr. Res. 2024, 543, 109219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oluba, O.M.; Muthusamy, S.; Subbiah, N.; Palanisamy, T. Sustainable Packaging Using Aloe Vera Infused Mango Starch–Wool Keratin Biocomposite Films to Extend the Shelf Life of Mango. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Dlala, S.; Mzoughi, Z.; Dammak, M.I.; Khwaldia, K.; Le Cerf, D.; Ben Halima, H.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; Korri-Youssoufi, H.; Majdoub, H. Eco-Friendly Films from Lemon Peel Pectin Including Essential Oils for the Sustainable Tomato Preservation. Process Biochem. 2025, 157, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zantar, Y.; Noutfia, Y.; Laglaoui, A.; Maurady, A.; Alfeddy, M.N.; El Abbassi, N.; Hassani Zerrouk, M.; Zantar, S. Impact of a Coating of Pectin and Cinnamomum Zeylanicum Essential Oil on the Postharvest Quality of Strawberries Packaged under Different Modified Atmosphere Conditions. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Huang, S.; Zou, L.; Ren, D.; Wu, X.; Xu, D. Application of Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose to Improve the Wettability of Chitosan Coating and Its Preservation Performance on Tangerine Fruits. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.V.D.d.B.S.; Diniz, A.G.; Guimarães Silva, V.B.; Buonafina-Paz, M.D.S.; dos Santos, J.E.F.; Costa, W.K.; de Souza Leão, V.L.X.; dos Anjos, F.B.R.; Barros Júnior, W.; Neves, R.P.; et al. Development of Edible Seaweed-Based Coating for Postharvest Preservation of Mangoes. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2025, 67, 103620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivany, F.M.; Aprilyandi, A.N.; Suendo, V.; Sukriandi, N. Carrageenan Edible Coating Application Prolongs Cavendish Banana Shelf Life. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, 8861610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Guo, N.; Yan, X.; Dong, J.; Chen, X.; Lu, H. Effect of ε-Polylysine Addition on Pullulan Biodegradable Films for Blueberry Surface Coating. Coatings 2023, 13, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, G.; Greco, G.; Salsi, G.; Garofalo, G.; Gaglio, R.; Barbera, M.; Greco, C.; Orlando, S.; Fascella, G.; Mammano, M.M. Effect of the Gellan-Based Edible Coating Enriched with Oregano Essential Oil on the Preservation of the ‘Tardivo Di Ciaculli’ Mandarin (Citrus Reticulata Blanco Cv. Tardivo Di Ciaculli). Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1334030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashooriyan, P.; Mohammadi, M.; Najafpour Darzi, G.; Nikzad, M. Development of Plantago ovata Seed Mucilage and Xanthan Gum-Based Edible Coating with Prominent Optical and Barrier Properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 248, 125938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Mei, S.; Su, X.; Chen, H.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, H.; Dai, C.; Luque, R.; Yang, D.-P. Integrating Waste Fish Scale-Derived Gelatin and Chitosan into Edible Nanocomposite Film for Perishable Fruits. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 191, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Riahi, Z.; Kim, J.T.; Rhim, J.-W. Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Gelatin Film Incorporated with Eggplant Peel Waste-Derived Carbon Dots for Active Fruit Packaging Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, J.; Ismail, N.; Tufail, T.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Rehman, A.; Ahmed, Z.; Xu, B. Technological Advancements in Zein-Based Nano-Colloids: Current Emerging Trends in Sustainable Packaging and Their Potential in Enhancing Shelf-Life of Fresh Fruits. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 49, 101523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; Ju, X.; Yuan, Y. A Review of Food Preservation Based on Zein: The Perspective from Application Types of Coating and Film. Food Chem. 2023, 424, 136403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarawneh, H.; Obeidat, H.; Shawaqfeh, S.; Al-massad, M.; Alrabadi, N.; Hiary, M.; Talhouni, M.; Alrosan, M. Effectiveness of Edible Coating in Extending Shelf Life and Enhancing Quality Properties of Golden Delicious Apple. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, W.; Wang, R.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zeng, X.-A. Cinnamaldehyde Enhanced Starch/Chitosan Composite Films: A One-Pot Engineered Solution for Extended Fruit Shelf Life. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 367, 123980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Sit, N. Comprehensive Review on Developments in Starch-Based Films along with Active Ingredients for Sustainable Food Packaging. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 39, 101534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-González, J.A.; Ramos-Bell, S.; Bautista-Baños, S.; Velázquez-Estrada, R.M.; Rayón-Díaz, E.; Martínez-Batista, E.; Gutiérrez-Martínez, P. Chitosan and GRAS Substances: An Alternative for the Control of Neofusicoccum Parvum In Vitro, Elicitor and Maintenance of the Postharvest Quality of Avocado Fruits. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa, K.E.V.; Pástor, P.G.M.; Cruz, P.S.S. Bioplásticos a partir de Almidón Modificado: Avances en Propiedades y Biodegradabilidad. Horiz. Académico 2025, 5, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Pérez, R.; Álvarez Castillo, A.; Olarte Paredes, A.; Salgado Delgado, A.M.; Hernández Pérez, R.; Álvarez Castillo, A.; Olarte Paredes, A.; Salgado Delgado, A.M. Obtención de nanocelulosa a partir de residuos postcosecha. Mundo Nano Rev. Interdiscip. Nanociencias Nanotecnología 2023, 16, 1e–47e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriboga, J. Hacia una agricultura más sostenible: Recubrimientos comestibles naturales para extender la vida útil de las frutas. VitalyScience Rev. Científica Multidiscip. 2025, 2, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nain, N.; Katoch, G.K.; Kaur, S.; Rasane, P. Recent Developments in Edible Coatings for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables. J. Hortic. Res. 2021, 29, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ali, A.; Ali, S.; Chen, H.; Wu, W.; Liu, R.; Chen, H.; Ahmed, Z.F.R.; Gao, H. Global Insights and Advances in Edible Coatings or Films toward Quality Maintenance and Reduced Postharvest Losses of Fruit and Vegetables: An Updated Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghababaei, F.; McClements, D.J.; Martinez, M.M.; Hadidi, M. Electrospun Plant Protein-Based Nanofibers in Food Packaging. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.V.d.S.; do Lago, G.V.P.; Pessoa, M.M.d.S.; Moraes, N.S.; Silva, M.J.B.; Alves, F.S.; Queiroz, R.N.; do Rego, J.d.A.R.; Brasil, D.d.S.B. Revestimentos de materiais por Leito Fluidizado e Leito de Jorro: Um estudo comparativo. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e92111738731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Kuang, Y.; Xu, P.; Chen, X.; Bi, Y.; Peng, D.; Li, J. Applications of Prolamin-Based Edible Coatings in Food Preservation: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 7800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.; Lall, A.; Kumar, S.; Dhanaji Patil, T.; Gaikwad, K.K. Plant-Based Edible Films and Coatings for Food-Packaging Applications: Recent Advances, Applications, and Trends. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1428–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohel, A.; Rani, R.; Mehta, D.; Nayak, M.K.; Patel, M.K. Quality Evaluation of Strawberries Coated with Water-in-Oil Based Emulsion Using an Advanced Electrostatic Spray Coating System. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 61, 1492–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradinezhad, F.; Adiba, A.; Ranjbar, A.; Dorostkar, M. Edible Coatings to Prolong the Shelf Life and Improve the Quality of Subtropical Fresh/Fresh-Cut Fruits: A Review. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günal-Köroğlu, D.; Karabulut, G.; Catalkaya, G.; Capanoglu, E. The Effect of Polyphenol-Loaded Electrospun Fibers in Food Systems. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 5094–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, S.; Gandhi, N.; Kaur, G.; Khatkar, S.K.; Bala, M.; Nikhanj, P.; Mahajan, B.V.C.; Sharma, D. Electrospray Application of Guava Seed Oil for Shelf Life Extension of Guava Fruit. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 2669–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Misra, M.; Subramanian, J.; Mohanty, A. Emerging Trends and Application of Edible Coating as a Sustainable Solution for Postharvest Management in Stone Fruits: A Comprehensive Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Kim-Lee, B.; Sun, X. Chitosan Coating Incorporated with Carvacrol Improves Postharvest Guava (Psidium guajava) Quality. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (21) CFR, Part 184: Direct Food Substances Affirmed as Generally Recognized As Safe. In Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. Fed. Regist, 184; Food and Drug Administration—FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 1988; pp. 459–461. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino, M.; Elechi, J.O.G.; Plastina, P.; Loizzo, M.R. Application of Natural Edible Coating to Enhance the Shelf Life of Red Fruits and Their Bioactive Content. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maro, M.; Gargiulo, L.; Gomez d’Ayala, G.; Duraccio, D. Exploring Antimicrobial Compounds from Agri-Food Wastes for Sustainable Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaş, H.; Kurek, M.A. Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Extraction of Polyphenols from Food Plants. Food Chem. 2024, 444, 138629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonino, C.; Difonzo, G.; Faccia, M.; Caponio, F. Effect of Edible Coatings and Films Enriched with Plant Extracts and Essential Oils on the Preservation of Animal-Derived Foods. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 748–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Hao, D.; Tian, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qin, G.; Pei, J.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Effect of Chitosan/Thyme Oil Coating and UV-C on the Softening and Ripening of Postharvest Blueberry Fruits. Foods 2022, 11, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen Arslan, H. Eco-Friendly Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Fruit and Vegetable Peels Demonstrates Great Biofunctional Properties. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 8930–8938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palos-Hernández, A.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C. Latest Advances in Green Extraction of Polyphenols from Plants, Foods and Food By-Products. Molecules 2025, 30, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polymers | Origin/Nature | Key Properties | Applications | Key Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Derived from chitin (crustaceans) | Antimicrobial, film-forming, biodegradable | Fresh-cut apple, reduced fungal growth | High cost; variable quality depending on deacetylation degree; limited solubility at neutral pH. | [92,93] |

| Starch | Tubers and grains | Film-forming, economical, requires plasticizers | Coated mangoes, reduced weight loss | High hydrophilicity; poor mechanical strength; sensitivity to humidity. | [94] |

| Pectin | Citrus and apple waste | Gas barrier, flexible in blends | Strawberries with cinnamon essential oil, improved color | High water sensitivity; requires blending for mechanical stability. | [95,96] |

| Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose | Derived from cellulose | Transparent, adhesive, hydrophobic | Mandarins, reduced transpiration | Relatively high cost; limited antimicrobial activity | [97] |

| Carboxymethyl cellulose | Derived from cellulose | Hydrophilic, emulsifier | Fruits (fresh pistachios) coated with nanoemulsions | High moisture sensitivity; potential stickiness on the fruit surface | [43] |

| Alginate | Brown algae | Gelation with Ca2+, O2 barrier | Mangoes (Kent), reduced browning | Requires calcium crosslinking; brittle films if not plasticized | [98] |

| Carrageenan (kappa) | Red algae | Forms gel, reduces respiration | Bananas, maintain firmness | Sensitivity to ionic strength; poor water resistance | [99] |

| Pullulan | Microbial polysaccharide | High transparency, O2 barrier | Blueberries, reduced dehydration | High production cost; sensitivity to humidity | [100] |

| Gellan gum | Bacterial polysaccharide | Stability, gelling agent | Mandarin, reduces P. digitatum | Brittle without plasticizers; limited availability in some regions | [101] |

| Xanthan gum | Microbial fermentation | High viscosity, stabilizer | Strawberries and grapes, mixed with starch | High viscosity may hinder uniform coating; often requires blending | [102] |

| Gelatin | Animal protein | Flexible, transparent | Coated strawberries, color retention | Sensory concerns (odor/taste); sensitive to high temperatures | [103,104] |

| Zein | Corn protein | Hydrophobic, grease barrier | Granny Smith apple, inhibits Listeria sp. | High cost; brittle structure without plasticizers | [105,106] |

| Whey proteins | Dairy by-product | O2 barrier, flexible | Golden Delicious apple, reduced browning | Allergenicity issues; sensitive to humidity | [107] |

| Nanocellulose | Derived from plant fibers | High mechanical strength | Strawberries, biodegradable packaging and maintain anthocyanins | High production cost; aggregation tendency; scalability challenges | [26,44] |

| Gum arabic | Acacia exudate | Emulsifier, water-soluble | Raspberries, grapes, and strawberries, mixed with essential oils | High solubility causes weak moisture barrier; cost variability | [42] |

| Method | Main Advantages | Main Limitations | Application on Fruit | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dip coating | Economical; requires simple equipment | Variable thickness; excess moisture | Apples, mangoes, strawberries, citrus fruits | [120] |

| Spraying | Thin, uniform coatings; adaptable to industrial scale | Greater investment in atomization equipment | Grapes, blueberries, tomatoes, peaches | [121] |

| Brushing/manual | Simple; useful in preliminary laboratory testing | Not very homogeneous; not scalable | Papayas, pears, bananas (exploratory trials) | [121] |

| Electro-spinning | Ultra-thin nanofibers; controlled release of bioactive compounds | Expensive; requires specialized equipment | Apples, strawberries, grapes (coatings with antioxidants) | [122] |

| Electro-spraying | Uniform layers with droplet size control | Experimental; limited to laboratory use | Blueberries, cherry tomatoes, strawberries | [123] |

| Fluidized bed | Uniform coverage of small particles | Initial development for fresh fruit; technical complexity | Blueberries, cherries, coated seeds | [24,124] |

| Nanoemulsification/Atomization | Ultra-thin layers improve controlled release of bioactive compounds | Experimental status; high technical level | Guava | [125] |

| Fruit Type | Fruit Example | Polysaccharide Matrix | Active Compound(s)/ Additive | Application Method | Quantitative Effects (vs. Control) | Shelf-Life Extension | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus | Mandarin, tangerine | Chitosan; gellan gum | Essential oils (oregano, thyme), phenolic extracts | Dipping/spraying | Weight loss ↓ 15–35%; better firmness; lower rind disorders; improved color retention | 7–12 days | [9,20,95,101] |

| Berries | Strawberry, blueberry | Chitosan; Carboxymethyl cellulose; pullulan | Essential oils; nanoemulsions; ε-polylysine | Dipping/coating | Weight loss ↓ 15–40%; delayed softening; higher anthocyanin retention; lower ΔE | 3–6 days | [35,43,44,120,131] |

| Tropical fruits | Mango, banana, papaya, guava, avocado | Starch; seaweed polysaccharides; chitosan | Plant extracts, essential oils | Dipping | Weight loss ↓ 15–35%; delayed softening; improved color; fewer physiological disorders | 5–8 days | [47,48,55,98,99,110] |

| Pome fruits | Apple, pear | Alginate; chitosan; polysaccharide blends | Essential oils; phenolic compounds | Dipping/spraying | Weight loss ↓ 10–25%; better firmness; reduced browning and scalding | 7–14 days | [41,54,67,107,121] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Culqui-Arce, C.; Paucar-Menacho, L.M.; Castro-Alayo, E.M.; Mori-Mestanza, D.; Medina-Mendoza, M.; Mori-Zabarburú, R.C.; Cruzalegui, R.J.; Vergara, A.J.; Vera, W.; Samaniego-Rafaele, C.; et al. Polymeric Biocoatings for Postharvest Fruit Preservation: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Polysaccharides 2026, 7, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides7010012

Culqui-Arce C, Paucar-Menacho LM, Castro-Alayo EM, Mori-Mestanza D, Medina-Mendoza M, Mori-Zabarburú RC, Cruzalegui RJ, Vergara AJ, Vera W, Samaniego-Rafaele C, et al. Polymeric Biocoatings for Postharvest Fruit Preservation: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Polysaccharides. 2026; 7(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides7010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleCulqui-Arce, Carlos, Luz Maria Paucar-Menacho, Efraín M. Castro-Alayo, Diner Mori-Mestanza, Marleni Medina-Mendoza, Roberto Carlos Mori-Zabarburú, Robert J. Cruzalegui, Alex J. Vergara, William Vera, César Samaniego-Rafaele, and et al. 2026. "Polymeric Biocoatings for Postharvest Fruit Preservation: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives" Polysaccharides 7, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides7010012

APA StyleCulqui-Arce, C., Paucar-Menacho, L. M., Castro-Alayo, E. M., Mori-Mestanza, D., Medina-Mendoza, M., Mori-Zabarburú, R. C., Cruzalegui, R. J., Vergara, A. J., Vera, W., Samaniego-Rafaele, C., Balcázar-Zumaeta, C. R., & Schmiele, M. (2026). Polymeric Biocoatings for Postharvest Fruit Preservation: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Polysaccharides, 7(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides7010012