1. Introduction

In the early decades of the 21st century, hydrogen and the associated concept of the hydrogen economy have emerged as strategic pillars in both global and European energy transition frameworks [

1]. Geopolitical and economic developments during the period 2019–2022 have markedly accelerated the imperative for diversification of energy sources, thereby fostering heightened interest in hydrogen technologies as a sustainable and environmentally responsible alternative to natural gas and other carbon-intensive energy carriers [

2]. In response, numerous European nations and leading industrial stakeholders have launched pilot programs and demonstration projects aimed at deploying hydrogen energy converters within industrial and residential sectors. These initiatives include facilities with individual installed capacities exceeding 10 MW, underscoring their alignment with the objectives of the “green transition” [

3].

Water electrolyzers, also referred to as hydrogen generators, have become the focus of intensive research and technological advancement, encompassing both chemical process engineering and structural design innovations [

4,

5]. Modern systems now surpass the 1 MW threshold in unit capacity, achieving electrical efficiencies of approximately 65% [

6]. Additional gains in overall system efficiency can be realized through the utilization of by-product heat, particularly in applications that integrate industrial and residential energy supply [

7]. In practice, however, the majority of installed capacities are based on proton exchange membrane (PEM) technology, which currently limits large-scale adoption, primarily due to the high capital cost of the generators and the associated technological maintenance requirements [

8,

9].

Zero gap-type hydrogen generators, also referred to as water electrolyzers, represent a relatively novel and attractive technology for the production of high-purity hydrogen for applications within the hydrogen energy sector [

10,

11]. These devices adopt the structural concept of conventional PEM water electrolyzers while offering additional advantages such as reduced cost, high energy efficiency, and simplified design [

12]. The electrochemical cells utilize porous metallic electrodes fabricated from non-noble metals in combination with thin diaphragms or separators for the spatial separation of the generated gases [

13]. These diaphragms/separators are capable of absorbing the electrolyte, thereby enabling ionic transport between the electrodes [

14,

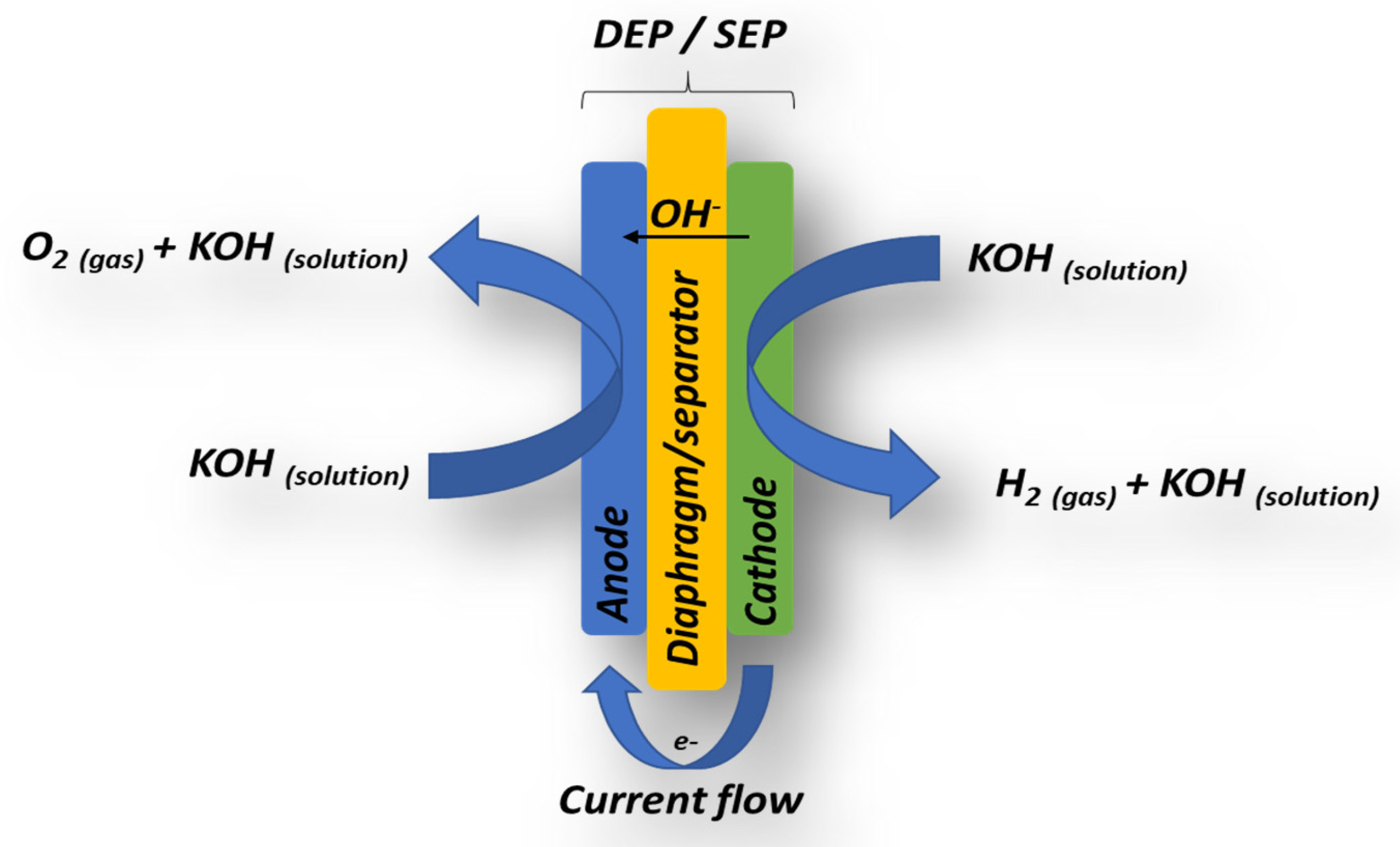

15]. This functional assembly, referred to as the diaphragm/separator–electrode package, is conceptually derived from the design principles of PEM-based hydrogen generators. A schematic representation of the diaphragm–electrode package is presented in

Figure 1.

The diaphragm/separator–electrode package (DEP) consists of two porous metallic electrodes positioned on either side of the diaphragm or separator. The electrolyte solution, typically 32% KOH, is introduced at the cathodic side of the DEP, where, under the influence of an applied electric current, water molecules are dissociated into hydrogen gas and hydroxyl ions (Equation (1)). The generated OH

− ions migrate through the doped diaphragm, reaching the anode side, where oxygen gas is evolved (Equation (2)). Thus, the two half-reactions are interconnected and collectively describe the overall electrochemical water-splitting process, as represented by Equation (3) [

16,

17].

The ionic conductivity in such systems is directly dependent on the concentration of electrolyte intercalated within the diaphragm or separator. Historically, asbestos materials with thicknesses ranging from 0.25 to 1 mm were employed for this purpose [

18]. In contemporary designs, diaphragms and/or separators such as CellGuard and Zirfon Perl UTP 500 offer substantially improved elasticity, mechanical durability, and electrolyte absorption capacity [

19,

20].

The primary structural components in zero-gap hydrogen generators are the porous metallic electrodes (

Figure 2). These functional units determine both the volume of generated gas and the overall overpotential of the system [

21]. Materials such as stainless-steel grades SS304 and SS316 exhibit satisfactory catalytic activity for both half-reactions, with degradation or corrosion rates on the order of approximately 1 mm per year under severe operational conditions [

22]. To reduce the overpotential of the individual half-reactions and optimize the overall energy efficiency of the system, stainless-steel structures—such as perforated meshes, woven anchor-type grids, and other configurations—are coated with more active catalytic layers [

23,

24]. These coatings effectively lower the operating voltage of individual diaphragm/separator–electrode packages (DEPs) and enhance the energy efficiency of the electrolytic process [

25].

Transition metals such as Ni and Fe, as well as their oxides and/or alloys, have been widely reported as effective and corrosion-stable catalysts for the oxygen evolution half-reaction [

26,

27,

28,

29]. In contrast, materials such as Ni, NiMo, NiFe, and NiCo exhibit high catalytic activity toward the hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline media [

30,

31,

32,

33]. When combined in optimized electrode structures, these materials can achieve current densities exceeding 1.2 A cm

−2 at a cell voltage of 2.4 V [

34].

One major challenge of zero-gap technology lies in the preparation of metal electrodes coated with alloys that are catalytically efficient for partial reactions [

35]. The classical or industrial approach involves the use of spray techniques followed by thermal treatment of the electrode [

36]. An alternative method for producing active catalytic layers is electrochemical deposition of metals via galvanic techniques [

37,

38]. Unfortunately, both approaches require high precision and are significantly energy-intensive, which increases the overall cost of the technology and limits its large-scale implementation [

39].

The deep-and-dry (D&D) method (also called DDM) represents an alternative approach for the fabrication of catalytically active electrode coatings [

40,

41]. Unlike conventional spray-coating and galvanic deposition, D&D enables precise incorporation of catalytic powders into porous metallic electrodes without requiring high-temperature post-treatment or complex electrochemical setups. This method offers improved uniformity, reduced energy consumption, and lower production costs, making it a promising technique for scalable preparation of electrodes in zero-gap hydrogen generators [

42].

Table 1 presents a comparison of electrode preparation methods.

To address the gap between electrode stability and cost for electrode fabrication in this study, the DDM was employed to fabricate stainless-steel mesh electrodes coated with highly efficient catalytic layers, applicable as both anodes and cathodes in zero-gap water electrolysis. Single-cell experiments were conducted using Zirfon Perl UTP 500 diaphragms (Agfa-Gevaert N.V., located in Mortsel, Belgium) doped with 25% KOH, and the performance of the system was investigated over a temperature range of 20 to 80 °C.

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental section of this study was structured into several sequential stages. First, high-performance metal-based electrodes were synthesized for application in zero-gap hydrogen generators, employing techniques to produce catalytically active coatings suitable for both anodic and cathodic operation. Next, the prepared substrates were subjected to comprehensive physicochemical characterization, including evaluation of their surface morphology, porosity, composition, and structural properties, to assess their suitability for electrochemical applications. Subsequently, the electrodes underwent preliminary electrochemical screening in a single-cell configuration using 25% KOH electrolyte, aimed at evaluating their catalytic activity and performance metrics. Finally, the electrodes were tested under realistic zero-gap cell conditions, employing a diaphragm–electrode package to investigate their operational behavior and efficiency under practical working conditions. To ensure the reproducibility and reliability of the obtained results, three independent electrodes were fabricated for each synthesis temperature under identical experimental conditions. All electrochemical measurements were repeated five times for each sample. The reported values represent the arithmetic mean of the repeated measurements, and the corresponding standard deviations (typically within 1–3%) are provided in the Results section.

Synthesis of high-performance metal-based electrodes: Metal mesh electrodes were fabricated from stainless steel (SS316) with a 0.5 mm-mesh opening of 0.5 mm and a wire thickness of 0.5 mm, configured in an anchor-type weave. The geometric surface area of each electrode was 16 cm

2 (4 cm × 4 cm × 1 mm). The electrodes were pretreated following the procedure described in [

43]. The five electrodes of identical dimensions were first acetone-cleaned (Alfa Aesar, Karlsruhe, Germany, Acetone, 99+%) for 15 min in order to remove organic contaminants from the surface. After the cleaning, they were subjected to etching in a 10% HCl (Alfa Aesar, HCl 36.5–38.0%) solution for 30 min for oxide/hydroxide layer dissolution and/or to slightly roughen the stainless-steel surface allowing the potential enhancement of the subsequent catalyst adhesion. Following the etching procedure, the electrodes were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water (to remove the residual acid and other impurities) and dried at room temperature (25 °C) for 24 h. The cleaned electrodes were denoted SSM.

Subsequently, the electrodes were immersed in a freshly prepared 0.01 M FeCl

3 solution (Alfa Aesar Iron(III) chloride, anhydrous, 98%) [

43] for 60 min, with the temperature strictly controlled for each sample in the range of 20° to 80 °C. The modified electrodes were denoted SS316-DDM, and 20 °C, 40 °C, 60 °C, and 80 °C were the temperatures during the D&D treatment. After treatment, the electrodes were again rinsed with deionized water and dried thermally in a laboratory oven (Dry Line model DL-12-Prime) at 70 °C for 60 min under an inert atmosphere. The drying temperature of 70 °C ensures complete removal of residual moisture without inducing undesired thermal stress or oxidation on the pretreated surface.

Physicochemical characterization of the prepared substrates: The morphology, structure, and metal composition of the electrocatalysts were also investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM)/energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) using a JEOL JSM 6390 electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an INCA Oxford elemental detector (Oxford Instruments, London, UK).

Electrochemical screening of the electrodes: The preliminary electrochemical characterization of the prepared mesh-type stainless-steel electrodes was carried out by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and linear sweep voltammetry (LSV). The potential scan rates were set to 100 mV s−1 for CV and 1 mV s−1 for LSV. All measurements were performed in a conventional three-electrode glass cell with a total electrolyte volume of 200 mL. The cell was equipped with a Luggin capillary positioned at a distance of 1–2 mm from the working electrode surface in order to minimize ohmic (iR) drop.

A 25% KOH aqueous solution (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA semiconductor grade, pellets, 99.99% trace metal basis, pH = 14) was used as the electrolyte. A spiral platinum wire (0.5 mm in diameter, 25 cm in length) served as the counter electrode, while a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE, Gaskatel HydroFlex®, Gaskatel GmbH, Kassel, Germany) was employed as the reference electrode. The electrochemical experiments were performed using a Gamry 1010E potentiostat–galvanostat (maximum current output of 1 A, Gamry Instruments Inc., Warminster, PA, USA), ensuring reliable control and high measurement accuracy.

Prior to each measurement, the electrolyte solution was purged with high-purity argon gas for 60 min to eliminate dissolved oxygen and other impurities, thereby ensuring reproducible and contamination-free experimental conditions.

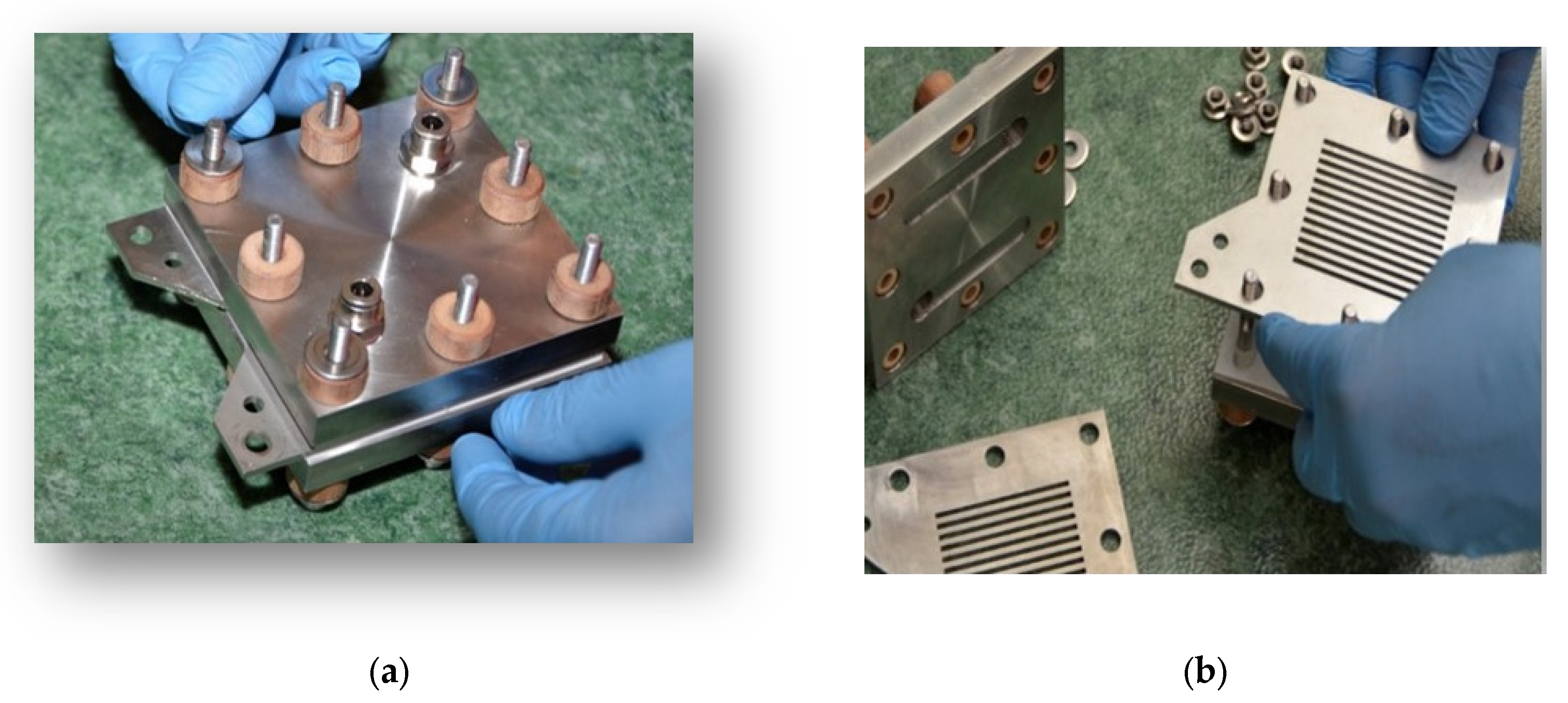

Electrochemical testing under realistic zero-gap cell conditions: The diaphragm–electrode packages (DEPs) were fabricated from two D&D-treated electrodes separated with a ZIRFON PERL UTP 500 separator (AGFA, Mortsel, Belgium). The DEPs were directly integrated within the prototype electrolysis cell (

Figure 3), registered as a utility model with the Bulgarian Patent Association at [BG/U/2019/4341] and with a mechanical strength of 8 N m per screw. The electrochemical performance of the DEPs was evaluated using linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) at cell voltages ranging from open-circuit voltage (OCV) V to 2.8 V, both at room temperature and at an elevated temperature of 80 °C. For these measurements, a Gamry Reference 3000 potentiostat–galvanostat equipped with an integrated booster capable of up to 30 A was employed. The electrolyte was circulated using a peristaltic pump (Hey Flow 120) controlled via an open-source Putty terminal program, with a dual-head configuration delivering a flow rate of 2 mL min

−1 to 20 mL min

−1 to each side of the cell. In addition to recording the overall cell voltage, the potentials corresponding to both partial reactions were monitored using a DAQ6008 data logger (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA), with data acquisition managed through Signal Express software version 2015. Long-term tests were performed using a Voltcraft DPPS-16-60 laboratory power supply with HCS 2.1 software (Conrad Electronic SE, Hirschau, Germany).

3. Results

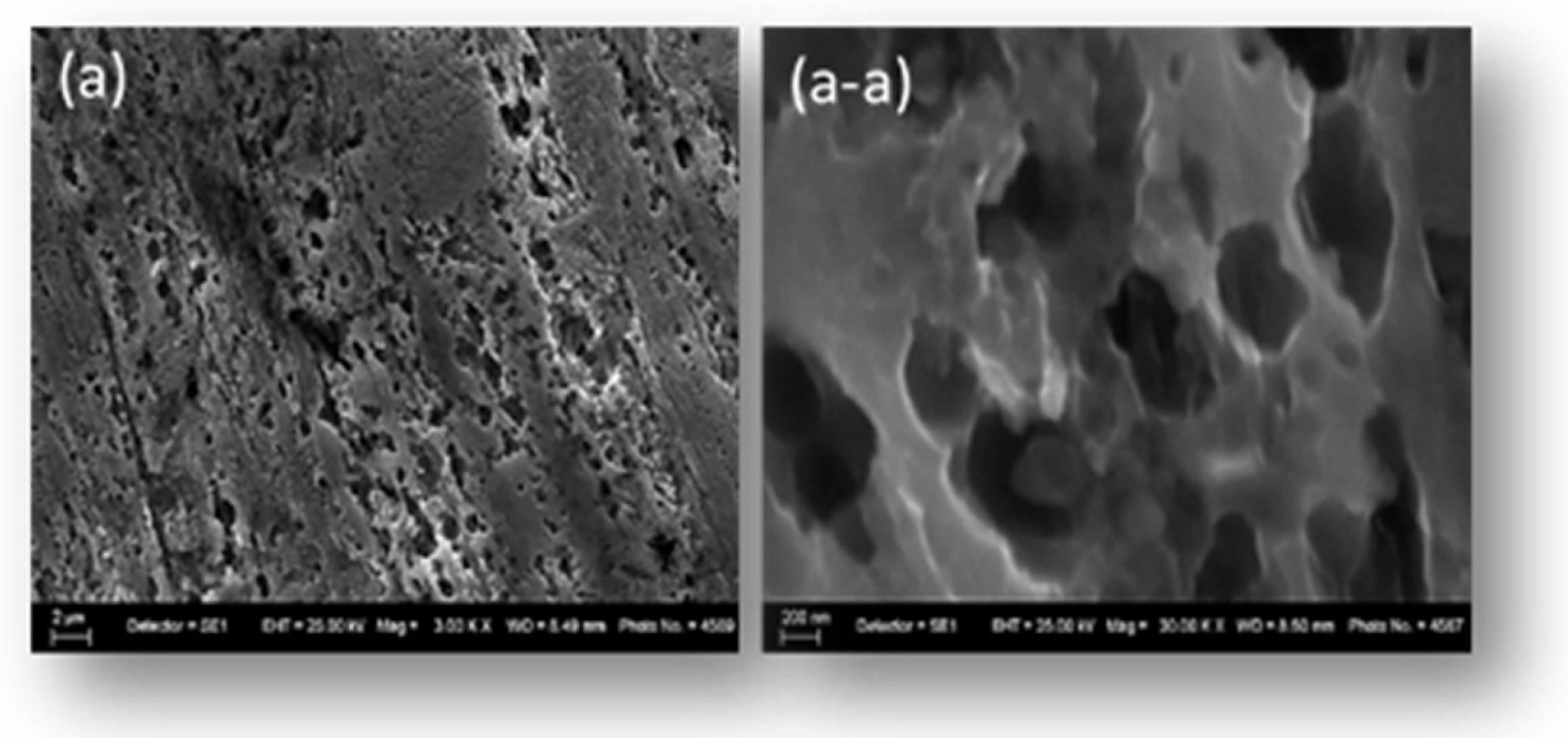

The morphology of the mesh-type stainless-steel electrodes (SS316) was examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) before and after surface cleaning. In

Figure 4a, the initial structure of the electrode reveals a relatively rough surface with the presence of microporosity and organic contaminants. Surface irregularities and small inclusions may affect the electrochemical activity and the uniformity of the catalytic coating.

After applying the cleaning procedure, shown in image (a-a), the electrode surface exhibits a more uniform structure with clearly visible pores and the removal of organic contaminants and the oxide layer. The microstructure becomes more open, which ensures improved adhesion of subsequent catalytic coatings and optimizes ion exchange within the electrode layer. The difference between the two states highlights the effectiveness of the cleaning procedure and the preparation of the electrodes for further functional coating.

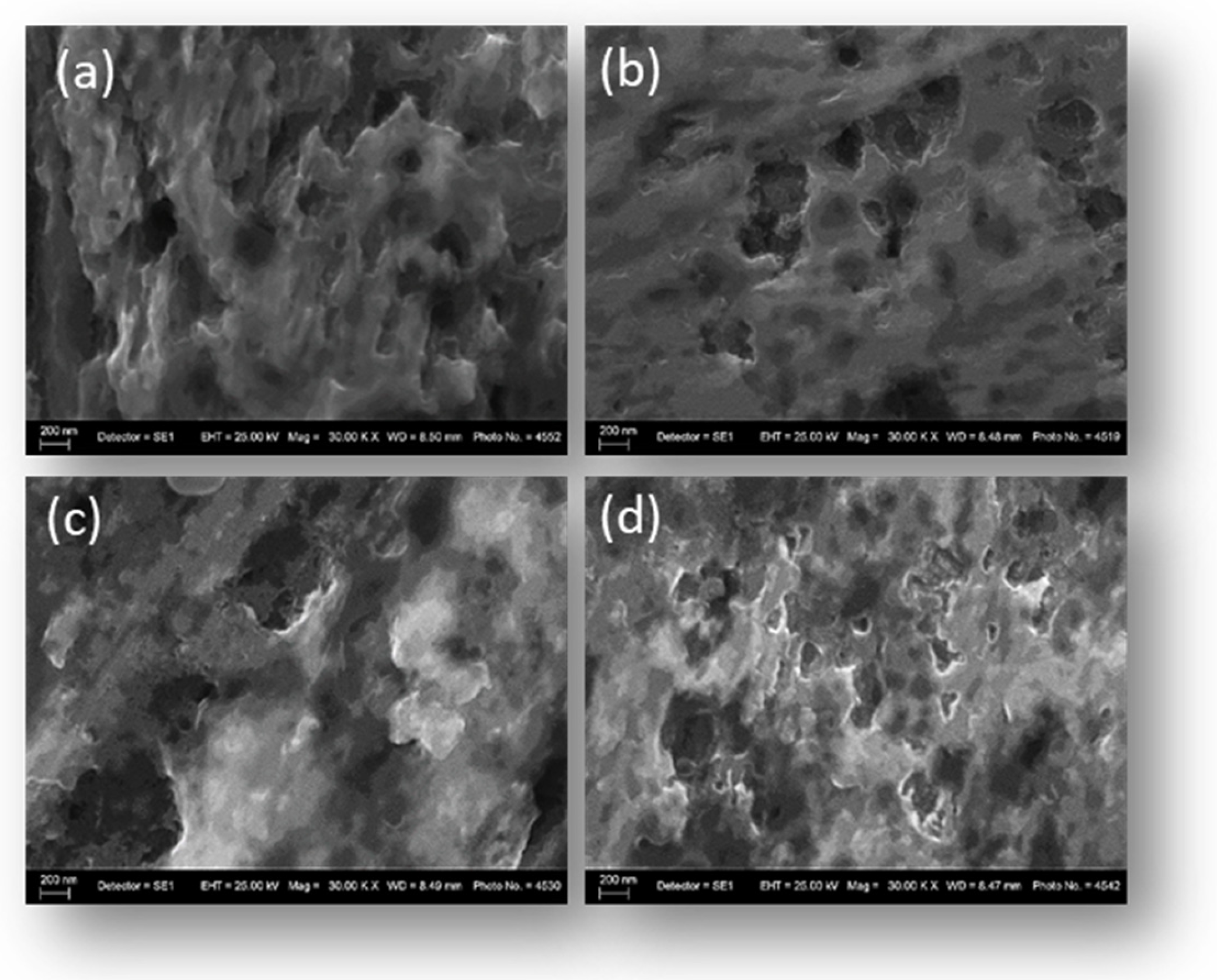

Figure 5 shows SEM micrographs of SS316 stainless-steel mesh electrodes modified with the Fe

3+ precursor using the deep-and-dry method at different processing temperatures: 20 °C (a), 40 °C (b), 60 °C (c), and 80 °C (d).

At 20 °C, the surface retains pronounced porosity and deep microcavities, indicating incomplete coverage. Increasing the temperature to 40 °C reduces pore depth and results in a more uniform layer. At 60 °C, the surface becomes compact and homogeneous with minimal defects, while at 80 °C, rapid solvent evaporation leads to microcrack formation and a network-like morphology. The results clearly demonstrate that the thermal treatment temperature is a key parameter in the deep-and-dry method, directly influencing the morphology and structural integrity of the coating. Moderate heating (40–60 °C) yields dense, uniform layers with minimal defects, while excessive heating (80 °C) accelerates solvent loss, causing stresses and microcracks that may compromise long-term stability. The most favorable morphology was obtained at 60 °C, combining maximum homogeneity and compactness without loss of structural integrity.

EDX analysis (

Table 2) revealed distinct variations in the elemental composition of the modified SS316 mesh electrodes as a function of processing temperature. For the unmodified substrate (SSM), the Fe and Ni content was determined to be 54.14% and 5.44%, respectively, with no detectable oxygen signal, consistent with the composition of the pristine stainless-steel surface.

Following modification with the Fe

3+ precursor, a pronounced decrease in the surface Fe and Ni signals was observed, accompanied by a concomitant increase in oxygen content. The lowest Fe content (40.36%) was recorded for the SS316-DDM60 sample, in agreement with the SEM observations (

Figure 5c), which revealed a compact and homogeneous surface morphology with minimal structural defects. The progressive increase in the oxygen content across the modified samples indicates a temperature-dependent enhancement of oxygen incorporation into the surface layer. Notably, the SS316-DDM60 electrode exhibits the highest catalytic activity and simultaneously one of the highest oxygen levels detected by EDX (5.77%). This enrichment in oxygen, together with the pronounced reduction in the Fe and Ni signals, suggests the formation of a more oxygen-rich surface phase—potentially mixed iron–nickel oxyhydroxides—that may play a key role in the improved electrocatalytic performance.

At lower processing temperatures (SS316-DDM20 and SS316-DDM40), higher Fe content and reduced oxygen levels (4.19–5.59%) were detected. These findings correlate with the SEM micrographs (

Figure 5a,b), which display pronounced porosity and deep microcavities at 20 °C, as well as a more uniform, yet still incompletely consolidated layer at 40 °C.

In contrast, the SS316-DDM80 sample exhibited the highest oxygen content (6.93%), which may be attributed to enhanced oxide formation due to rapid solvent evaporation at elevated temperature. However, SEM analysis (

Figure 5d) revealed a network-like morphology with microcracks, indicative of internal stress development and partial loss of structural integrity. The formation of such defects at high temperature is likely a consequence of accelerated solvent loss, leading to contraction stresses within the coating layer. The optimal balance between complete substrate coverage, compositional modification, and structural stability was achieved at 60 °C, where the coating exhibited maximal suppression of metallic signals (Fe, Ni) and a substantial oxygen presence without the emergence of microstructural defects such as cracking.

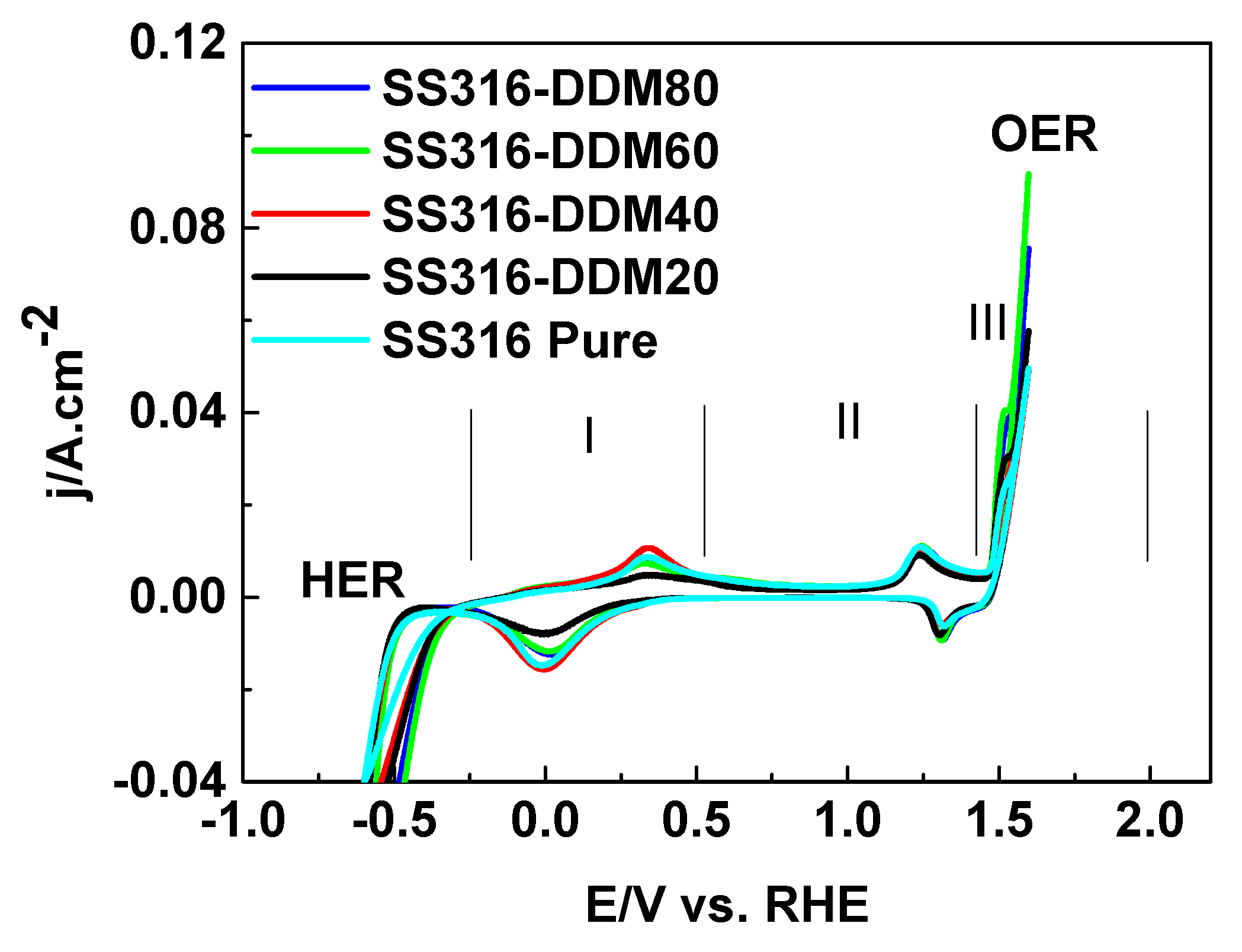

Following physicochemical characterization, the prepared electrodes were assembled in a three-electrode configuration with a liquid electrolyte for preliminary electrochemical screening. Cyclic voltammograms (CVs) were recorded within the typical potential window for electrolysis in 25% KOH alkaline solution, as presented in

Figure 6.

The cyclic voltammograms exhibit the characteristic redox features of SS316 stainless steel, with well-defined anodic and cathodic peaks corresponding to surface oxidation and subsequent reduction processes, respectively. The overall shape and integrated areas of the CV curves are comparable across all samples, indicating that the electrochemically accessible surface area remains essentially unchanged following the different thermal treatments. Notably, the anodic peaks observed in the positive potential region, associated with the oxidation of surface species, are fully reversible, as evidenced by the corresponding cathodic peaks in the negative sweep. This electrochemical reversibility suggests that no significant irreversible processes—such as corrosion or permanent surface degradation—occur under the tested alkaline electrolyte conditions.

Regions I–III (including OER) in

Figure 6 were associated with redox transitions of the SS316 composed metals Fe, Cr, and Ni in accordance with [

44], as follows:

- (I).

Iron redox couples Fe ↔ FeOOH ↔ Fe2O3/Fe3O4

- (II).

Nickel redox couples (Ni ↔ Ni(OH)2 ↔ NiOOH)

- (III).

Chromium passive layer formation (Cr2O3/Cr(OH)3)

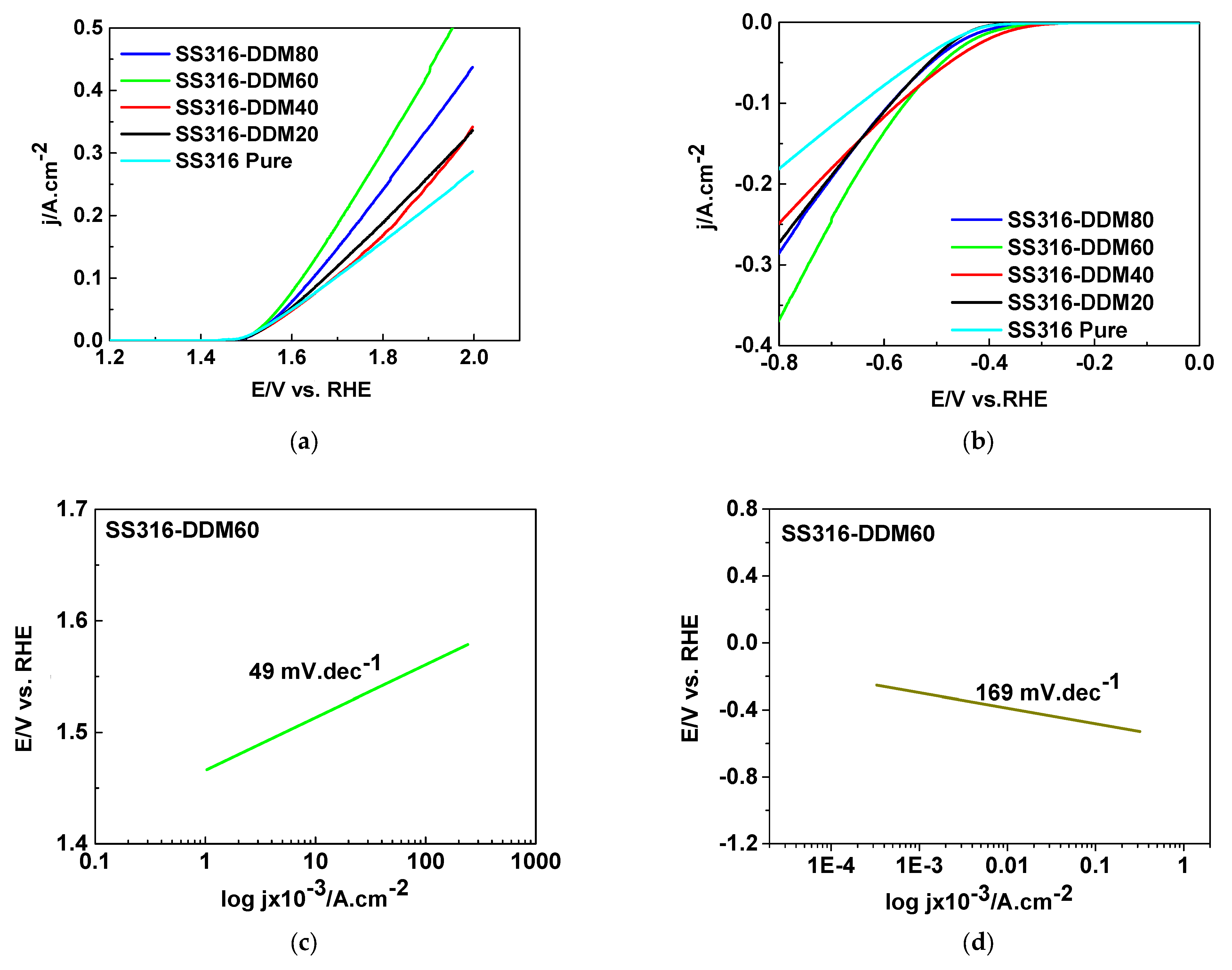

To evaluate the catalytic activity of the samples prepared via the deep-and-dry method (DDM), polarization curves for both the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) were recorded. The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) profiles corresponding to the anodic OER process are presented in

Figure 7.

The anodic polarization curves for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), presented in

Figure 7a, indicate that the reaction onset potential is approximately 1.50 V vs. RHE for all investigated electrodes. Upon further increase in potential, the current density reaches ~0.38 A·cm

−2 for electrodes prepared at 20 °C and 40 °C. Increasing the processing temperature to 60 °C leads to a marked improvement in catalytic activity, with the current density rising to ~0.58 A·cm

−2. However, at 80 °C, the current density decreases, suggesting a deterioration in catalytic performance.

The obtained overpotentials for OER of the DDM treated electrodes are presented in

Table 3.

As can be seen, the highest current densities were obtained on the SS316-DDM60 electrode. The Tafel slope was obtained from the LSV curve (

Figure 7c), and was equal to ∼49 mV dec

−1, indicating enhanced activity at high-concentration OH

− conditions (pointing to O–O bond formation as the rate-determining step (RDS) under these optimized conditions).

The cathodic polarization curves for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), shown in

Figure 7b, display an onset potential of approximately −0.55 V vs. RHE for all samples. The highest current densities are again recorded for the 60 °C sample, while the 20 °C and 40 °C electrodes exhibit lower performance and the 80 °C sample demonstrates a decline in activity similar to the OER trend. These electrochemical observations are in strong agreement with the morphological and compositional findings from SEM and EDX analyses. The superior catalytic performance of the 60 °C sample correlates with its compact, homogeneous, and defect-free coating morphology, as revealed by SEM, which facilitates efficient charge transfer and minimizes resistive losses.

The Tafel slope of the HER reaction over the SS316-DDM60 electrode (

Figure 7d) was obtained from the LSV curve from

Figure 7b and was equal to ~169 mV dec

−1. The obtained value indicates that the RDS for HER is the water dissociation process.

The obtained overpotentials for HER of the bare SSM and the DDM-treated electrodes are presented in

Table 4.

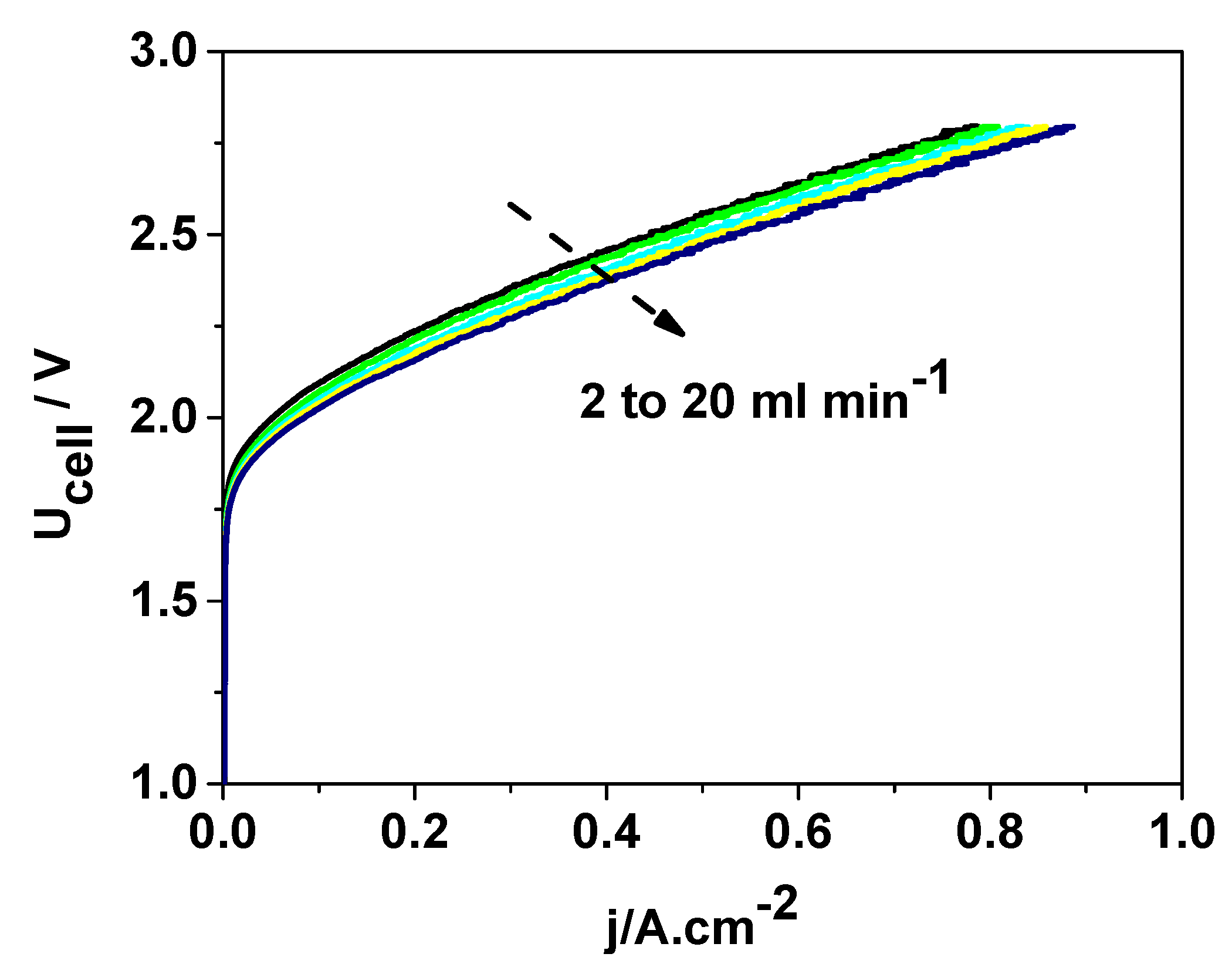

To assess the electrochemical behavior of the SS316-DDM60 sample under conditions approximating practical operation, DEP/SEP measurements were carried out following the procedure described in the Experimental section. The resulting U–j polarization curves at 25 °C are shown in

Figure 8.

The voltammogram exhibits the characteristic shape and behavior of a hydrogen generator equipped with a DEP/SEP. Gas evolution initiates at a terminal voltage of approximately 1.9 V, which decreases to around 1.8 V with increasing electrolyte flow through the electrode. The current density reaches ~0.75 A cm−2 at 2.8 V, and at higher flow rates (≈20 mL min−1 cm−2), this value increases by about 10%. Such trends reflect the influence of electrolyte flow on mass-transport phenomena: enhanced electrolyte circulation facilitates the removal of evolved gas bubbles from the electrode surface, thereby reducing concentration overpotentials, while simultaneously improving the supply of fresh electrolyte to the interior of the diaphragm separator. These combined effects contribute to the observed improvement in cell performance at elevated flow rates.

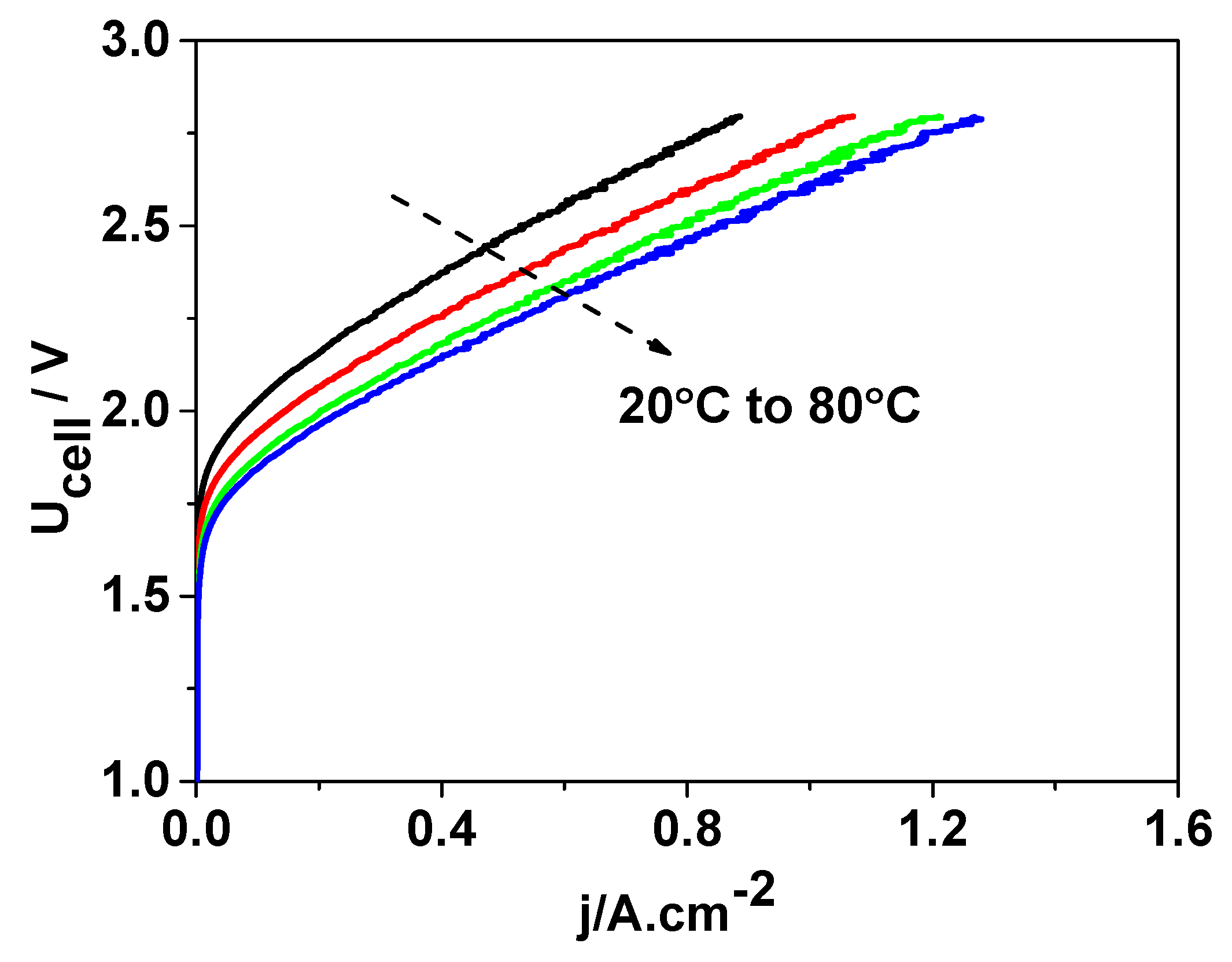

To further investigate the performance of the developed DEP/SEP, the operating temperature of the cell was increased, thereby enhancing the ionic conductivity of the doped electrolyte. The corresponding results are presented in

Figure 9.

Increasing the operating temperature of the cell resulted in a decrease in the onset cell voltage from approximately 1.85 V at 20 °C to 1.70 V at 80 °C, which significantly improved the overall energy efficiency of the electrolyzer. Furthermore, at elevated temperatures, the current density reached values of about 1.4 A cm−2, corresponding to an increase in hydrogen production by approximately two-thirds compared to operation at room temperature.

In order to evaluate the stability of the DEP and the overall cell, stationary measurements were performed at an elevated temperature of 80 °C under low- and high-constant-power operation. The obtained results are presented in

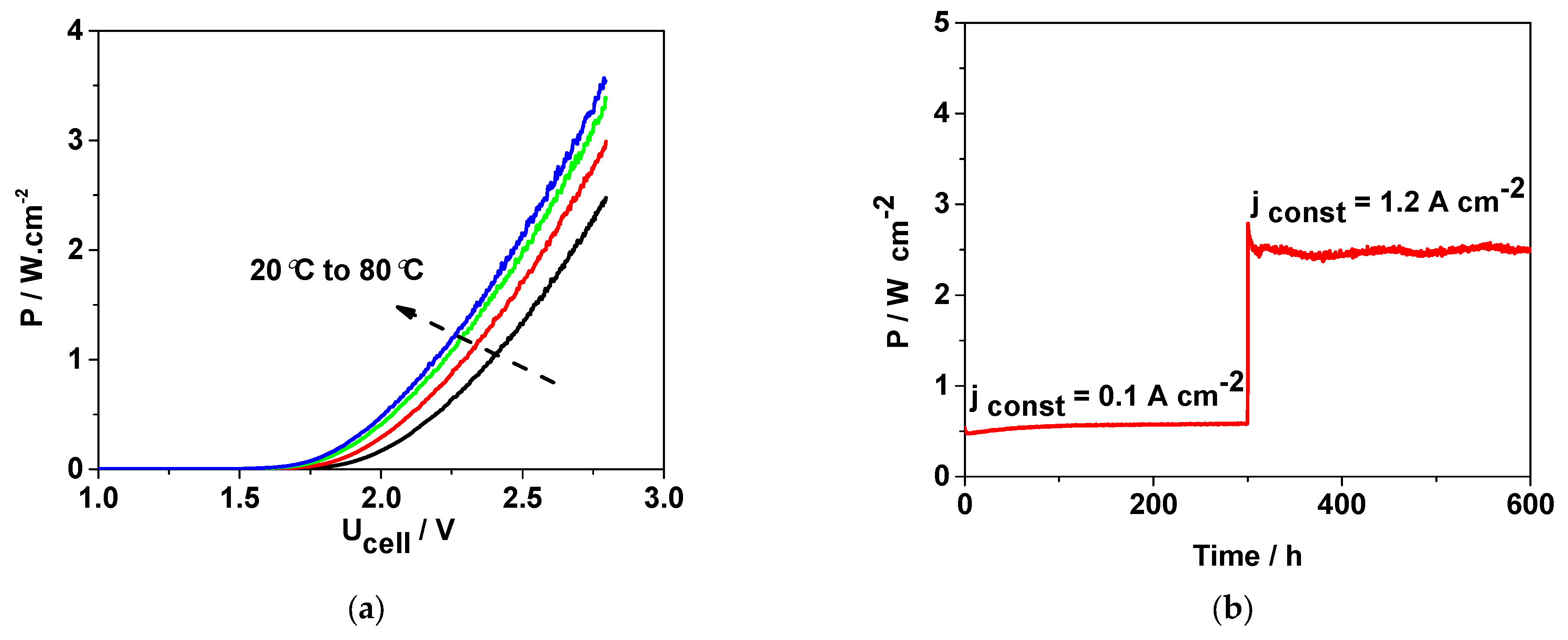

Figure 10.

Figure 10a illustrates the strong dependence of cell power on operating temperature. At 80 °C, the cell demonstrates the lowest operating mode, with power densities below 0.5 W·cm

−2, while the maximum power density of the DEP reaches approximately 3.5 W·cm

−2. These results highlight the critical influence of temperature on the achievable power output.

The stability of the DEP under different operating regimes is presented in

Figure 10b. At a relatively low specific power of 0.5 W·cm

−2, the cell maintained stable performance for nearly 300 h without significant deviations. However, when the applied power was increased to 3 W·cm

−2, minor fluctuations appeared in the recorded curve. These instabilities can be attributed mainly to irregularities in electrolyte supply and distribution at the electrode surface. Long-term stability tests are ongoing to provide further insights into the durability of the system under extended operation.

The deep-and-dry method (DDM)–modified SS316 electrode developed in this study demonstrates performance comparable to or exceeding that of conventional Ni- or Pt-based systems. Data for other studies are derived from Chen and Hu (1.57 W cm

−2, NiMo/Fe-NiMo), Zappia et al. (1.68–16.7 W cm

−2, Pt/C||SS mesh), Pushkareva (1.78 W cm

−2, Ni-based), Borisov et al. (1.2 W cm

−2, NiFeCoP on Ni foam), and Zuo et al. (1.7–8.4 W cm

−2, activated SS meshes) [

34,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50].

Figure 11 summarizes the performance of the DDM-modified stainless-steel electrodes developed in this work relative to representative zero-gap alkaline electrolyzers reported in recent studies. The present electrodes reach a power density of 3.5 W cm

−2 (1.2 A cm

−2 at 2.0 V, 80 °C), outperforming several conventional Ni- and SS-based configurations operated under comparable conditions. This result highlights the potential of DDM treatment as a scalable, low-cost approach for fabricating durable electrodes for industrial alkaline electrolysis.