Abstract

As critical reservoirs of biodiversity and providers of ecosystem services, wetland ecosystems play a pivotal role in maintaining global ecological balance. They not only serve as habitats for diverse aquatic and terrestrial organisms but also play substantial roles in water purification, carbon sequestration, and climate regulation. However, intensified anthropogenic activities—including drainage, fertilization, invasion by alien species, grazing, and urbanization—pose unprecedented threats, leading to profound alterations in the functional traits of wetland plants. This review synthesizes findings from peer-reviewed studies published between 2005 and 2024 to elucidate the mechanisms by which human disturbances affect plant functional traits in wetlands. Drainage was found to markedly reduce plant biomass in swamp ecosystems, while mesophyte and tree biomass increased, likely reflecting altered water availability and species-specific adaptive capacities. Mowing and grazing enhanced aboveground biomass and specific leaf area in the short term but ultimately reduced plant height and leaf dry matter content, indicating potential long-term declines in ecological adaptability. Invasive alien species strongly suppressed the growth of native species, reducing biomass and height and thereby threatening ecosystem stability. Eutrophication initially promoted aboveground biomass, but excessive nutrient inputs led to subsequent declines, highlighting ecosystems’ vulnerability to shifts in trophic state. Similarly, fertilization played a dual role: moderate inputs stimulated plant growth, whereas excessive inputs impaired growth performance and exacerbated eutrophication of soils and water bodies. Urbanization further diminished key plant traits, reduced habitat extent, and compromised ecological functions. Overall, this review underscores the profound impacts of anthropogenic disturbances on wetland plant functional traits and their cascading effects on ecosystem structure and function. It provides a scientific foundation for conservation and management strategies aimed at enhancing ecosystem resilience. Future research should focus on disentangling disturbance-specific mechanisms across different wetland types and developing ecological engineering and management practices. Recommended measures include rational land-use planning, effective control of invasive species, and optimized fertilization regimes to safeguard wetland biodiversity, restore ecosystem functions, and promote sustainable development.

1. Introduction

As one of the most diverse and productive ecosystems on Earth, wetlands encompass a wide range of habitats, including swamps, peatlands, lakes, and saline soils, and play an irreplaceable role in water purification, carbon storage, and flood regulation [1]. They provide essential habitats for numerous plant and animal species and are critical for maintaining ecological balance. Wetland plants not only form the foundation of food webs but also contribute to soil improvement, water regulation, and nutrient cycling [2]. However, wetlands are among the ecosystems most strongly affected by human activities, such as urban development, pollution, invasive alien species, overgrazing, eutrophication, and agricultural drainage. These anthropogenic disturbances alter the physical and chemical properties of wetlands and significantly influence the functional traits of wetland plants [3,4]. Functional traits, defined as morphological, physiological, and phenological characteristics related to growth, reproduction, and survival, directly determine plants’ roles in ecosystems and their capacity to adapt to environmental change [5]. These traits are inherently linked to the Plant Economics Spectrum (PES)—a core ecological framework that organizes plant strategies along a continuum from resource-acquisitive (high specific leaf area, low leaf dry matter content) to resource-conservative (low specific leaf area, high leaf dry matter content) [5]. Additionally, trait responses to disturbances align with Grime’s CSR (Competitor-Stress Tolerator-Ruderal) model, where disturbances filter plant strategies by favoring traits adapted to competition, stress resistance, or rapid colonization [6]. Grime’s CSR theory categorizes plant strategies based on competition, stress, and disturbance. Intensified anthropogenic disturbances act as strong filters, selecting for trait syndromes aligned with these frameworks, thereby re-shaping ecological processes and ecosystem functioning.

Intensified disturbances may trigger plastic responses in these traits, thereby reshaping ecological processes and ecosystem functioning. To quantify such plasticity, common methodologies include reaction-norm analyses under controlled environmental gradients, the calculation of plasticity indices (e.g., the Relative Distance Plasticity Index, RDPI) for field comparisons, and multivariate assessments of integrated trait syndromes [6,7]. Recent research has increasingly focused on the mechanisms by which wetland plant traits respond to specific disturbance types. For instance, invasive alien species not only exacerbate competitive pressures on native plants but also alter community structure, ecosystem functioning, and ecological processes [8]. Overgrazing reduces plant biomass and species diversity [9], while eutrophication decreases dissolved oxygen concentrations in water bodies, impairing plant growth, photosynthesis, and plant–microbe interactions [10]. Moreover, plant responses to disturbances show considerable interspecific variation, with some species exhibiting strong adaptability and others facing heightened extinction risk [11]. Such variability in plant functional traits affects not only individual fitness but also the stability, functioning, and service provision of wetland ecosystems [12].

The aim of this paper is to review the current research on the effects of anthropogenic disturbances on wetland plant functional traits, to explore the specific mechanisms underlying the impacts of different disturbance types, and to analyze the potential consequences of these changes on wetland ecosystem functions. We will discuss future research directions and management recommendations, aiming to provide a scientific basis for wetland conservation and management and promote the sustainable development of wetland ecosystems. Through a deeper understanding of the adaptive mechanisms and ecological functions of wetland plants, we will be able to better manage the challenges posed by human activities and maintain and restore the ecological health and functions of wetlands.

2. Literature Acquisition and Data Classification

We conducted a systematic literature review using the Web of Science database. The search strategy incorporated combinations of keywords related to wetland types, anthropogenic disturbances, plant groups, and functional traits. Specifically, the search query was TS = (“wetland” OR “peatland” OR “peat” OR “fen” OR “bog” OR “swamp” OR “marsh” OR “mire” OR “freshwater lake” OR “floodplain”) AND TS = (“graze” OR “mow” OR “vegetation removal” OR “vegetation replacement” OR “damming*” OR “ditching*” OR “invasive species*” OR “eutrophication” OR “drainage” OR “human interference” OR “artificial pressure” OR “anthropogenic disturbance” OR “fertilize*”) AND TS = (“plant” OR “vegetation” OR “grass” OR “macrophyte” OR “moss” OR “sedge” OR “herb” OR “shrub” OR “tree” OR “wood”) AND TS = (“functional trait” OR “aboveground” OR “belowground” OR “biomass” OR “height” OR “chlorophyll content” OR “leaf area” OR “leaf area index” OR “leaf C/N/P content” OR “leaf C:N” OR “leaf C:P” OR “leaf N:P” OR “leaf dry matter content” OR “specific leaf area” OR “root mass” OR “root traits” OR “stem traits”). We systematically searched all peer-reviewed English-language journal articles published between 2005 and 2024, yielding 1594 results. To ensure the reliability of included studies, we implemented basic quality screening criteria during the selection process: (i) studies must clearly define the anthropogenic disturbance type (e.g., explicit drainage intensity, nutrient addition rate) and quantify trait responses (e.g., biomass, height measurements with units); (ii) study sites must be explicitly classified as wetlands (with hydrological or vegetation criteria provided); (iii) functional traits must be measured using standardized methods (e.g., specific leaf area following standard protocols [7]). These criteria effectively excluded low-quality or irrelevant studies, addressing concerns about study quality assessment. Inter-rater reliability was verified by two independent researchers (J.W. and Z.L.) who screened 30% of the literature, with a consistency rate of >90% (resolving discrepancies via discussion with C.L.). After screening titles, abstracts, and full texts, 166 publications were selected for analysis (Supplementary Table S1). Studies were excluded if (i) the investigation of disturbances did not clearly distinguish anthropogenic from natural drivers (e.g., atmospheric nitrogen deposition), (ii) the study sites were not wetlands (e.g., meadows), or (iii) the focus was not on plant functional traits (e.g., traits of invasive fauna). The aim was to explore the effects of anthropogenic disturbances on wetland plant functional traits, with an emphasis on recent advances and emerging trends (Supplementary Figure S1). While we acknowledge that restricting the search to Web of Science may miss some regional studies, this choice aligns with methodological practices in some trait-based wetland reviews, which relied on single core databases to ensure systematic screening of peer-reviewed literature. Web of Science’s comprehensive coverage of global ecological journals (including Google Scholar / Scopus-indexed titles via cross-citation integration) and rigorous peer-review filter minimized selection bias for core research on wetland plant functional traits. To further enhance transparency, we have supplemented Supplementary Table S1 with full bibliographic details of all included studies, enabling readers to assess the breadth of literature coverage. The selected literature covered diverse wetland types, plant organs, and disturbance regimes. All relevant data were extracted verbatim following authors’ terminology, including the precise botanical nomenclature and taxonomic classifications reported in the original publications, and then categorized by wetland type, disturbance pattern, and plant functional trait. The geographic coordinates of the study sites were obtained directly from the publications or derived from reported location information.

To facilitate synthesis, five categories of anthropogenic disturbance were identified following previous classification schemes [12,13]: (1) vegetation removal (grazing, mowing), (2) invasive alien species, (3) drainage, (4) nutrient enrichment (eutrophication, fertilization), and (5) other. The last category included urbanization, damming, and studies that did not specify disturbance type.

Wetland types were grouped into seven categories: coastal wetlands (including mangroves and estuarine deltas), lake wetlands, rivers and estuaries, marshes, peatlands, swamps, and artificial waterbodies.

For visualization, we mapped 386 sample sites globally using ArcGIS Desktop 10.8 (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). Data analysis and visualization were performed with OriginPro 2022 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) and RStudio (version 2024.04.1+748, Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA, USA. While some relevant studies may not have been captured, we believe that the extensive search and rigorous selection process enabled robust and unbiased conclusions.

3. Temporal and Spatial Distribution of Studies over the Past Two Decades

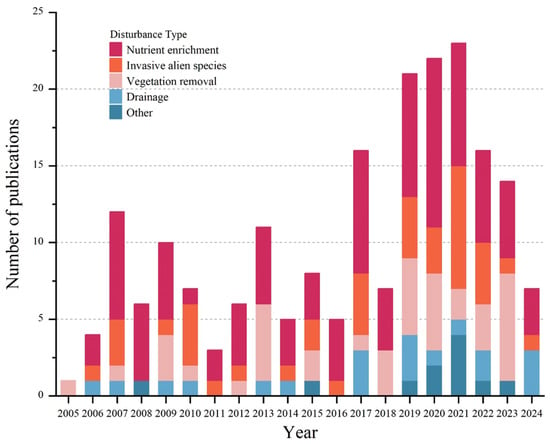

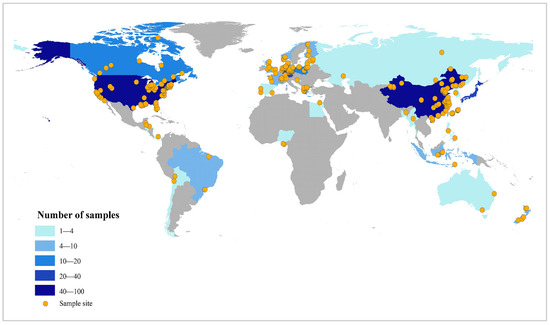

To reveal temporal trends in anthropogenic disturbances, we summarized the 166 selected studies published over the past 20 years using stacked plots (Figure 1). More than half of these articles were published in the last decade. Drainage and invasive alien species were consistently reported each year, with 19 and 40 studies, respectively. Nutrient enrichment emerged as the most frequently studied disturbance, accounting for 94 publications (over 50% of the total). Research on the effects of anthropogenic disturbances on wetland plant functional traits was most active between 2017 and 2023, when 119 studies were published, whereas fewer than 10 studies appeared during 2004–2006. Spatially, our global sample sites (386 in total, Figure 2) cover major wetland biomes across Asia, Europe, North America, Africa, Central America, and Oceania, with representation of all key wetland types (coastal, swamp, riverine, lake, artificial) as classified by the Ramsar Convention. While geographical coverage is comprehensive, we acknowledge underrepresentation in Africa (3 sites), Central America (4), and Oceania (7), which reflects both regional research gaps and data availability constraints. This spatial pattern is consistent with global wetland research trends and provides sufficient power to reveal general trait-disturbance relationships [12]. More refined spatial analyses (e.g., biogeographic realm-specific patterns) are proposed as future research directions.

Figure 1.

Number of publications per year categorized by disturbance type.

Figure 2.

Global distribution of sampling sites from studies on wetland plant functional traits under anthropogenic disturbances. The colors correspond to sample quantity intervals (see legend), where a darker hue indicates a higher sample count range. Areas shaded in grey represent regions not covered by the current dataset.

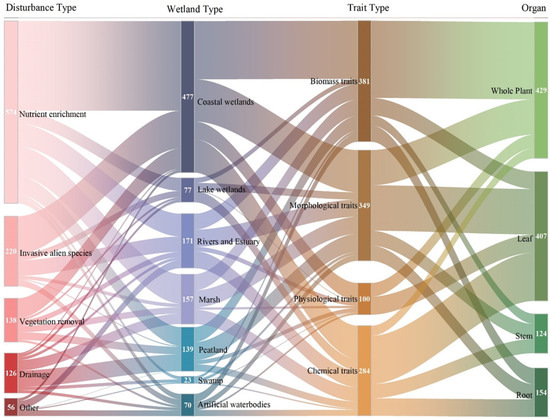

The reviewed studies covered a wide range of disturbances, with nutrient enrichment (574 cases), invasive alien species (220), vegetation removal (138), drainage (126), and other disturbances (56; e.g., urbanization, damming) all shown to affect plant functional traits. Traits were reclassified into biomass traits (381), morphological traits (349), physiological traits (100), and chemical traits (284). Research most frequently examined whole-plant traits (429 records) and leaf traits (407), whereas stem (124) and root (154) traits received less attention.

Among different wetland types, coastal wetlands were most extensively studied (477 records), including mangroves, deltas, and tidal wetlands. Swamps (319) represented the most diverse category, encompassing herbaceous marshes, peatlands, and inland salt marshes. Rivers and estuaries accounted for 171 studies, primarily riparian wetlands and floodplains. Lake wetlands were addressed in 77 studies, covering both freshwater and saline lakes. Finally, 70 studies focused on artificial waterbodies, such as ponds and man-made lakes (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The frequency of combinations between disturbance type, wetland type, plant organ, and functional trait type in all collected studies. The thickness of the lines is proportional to the number of categories (Table 1). Numbers at nodes indicate the count of unique categories within each dimension, and text labels adjacent to bands specify the individual categories. Distinct colors represent the four major analytical dimensions.

Table 1.

Plant traits and their categories, organs, and abbreviations.

4. Impact of Anthropogenic Interference on Plant Functional Traits

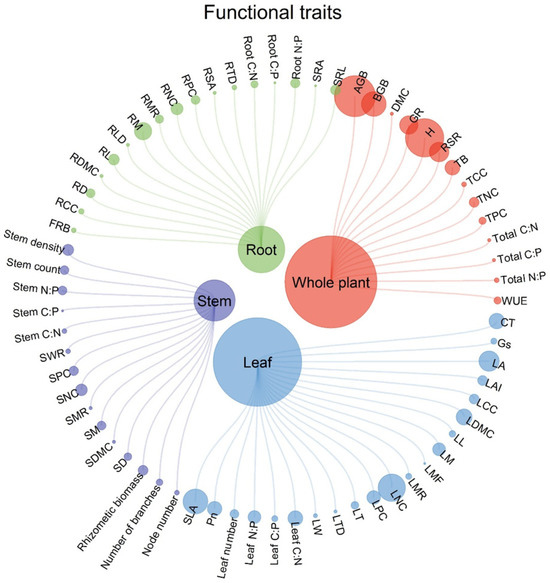

Plant functional traits are key physiological and morphological characteristics that determine how plants interact with their environment. In this study, traits were classified into four major categories, with particular attention to three primary organs: roots, stems, and leaves.

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of trait categories across plant organs. We identified 68 functional traits—18 biomass-related, 21 morphological, 24 chemical, and 5 physiological traits; these traits are widely recognized indicators of plant responses to various anthropogenic disturbances, including vegetation removal, invasive alien species, drainage, and nutrient enrichment (Table 1). To establish a clear link between disturbance types and plant trait responses, we first retrieved data from the collected literature (Table S1) on the main consequences—promoting, reducing, or having no effect—of anthropogenic disturbances on different traits. This information was then synthesized to reveal distinct response patterns across disturbance types, which are summarized in Table 2. Formal meta-analysis was not possible due to extreme heterogeneity in data formats (e.g., biomass reported as g/m2 vs. kg/ha), measurement units, and experimental designs across global studies. Vote-counting was selected as the analytical framework because it preserves data integrity across highly heterogeneous global studies (varying units, experimental designs, trait types) and effectively identifies overarching response patterns—consistent with methodological standards for multi-trait, multi-disturbance syntheses. To address concerns about effect size, we supplemented vote-counting with quantitative summary statistics in Supplementary Table S2, which reports the percentage of studies showing positive/negative/neutral responses for key traits (e.g., AGB, plant height) under each disturbance type. Conflicting findings (e.g., divergent AGB responses to drainage) are explicitly discussed in Section 4.1, linked to species-specific adaptability and disturbance duration.

Figure 4.

Functional trait and plant organ category distribution of the included studies. The size of the terminal node shows the quantitative proportion of publications including this trait.

Table 2.

List of most commonly measured functional traits (abbreviations) from 166 studies included in this review, including their definition, their key role in plant functioning, and the observed direction of their response to anthropogenic disturbances based on the literature.

4.1. Drainage

The construction of drainage systems represents one of the most widespread human modifications of wetland ecosystems. By altering natural hydrological regimes, drainage significantly lowers water tables, modifies soil moisture conditions, and accelerates the decomposition of organic matter. These changes inevitably exert selective pressures on wetland vegetation, driving shifts in plant community structure and functional traits. Over the past two decades, numerous studies have documented how drainage-induced hydrological and biogeochemical changes influence key plant functional traits—such as above- and belowground biomass allocation, nutrient acquisition strategies, and leaf characteristics—reflecting broader adaptive responses to altered environmental conditions.

Specifically, drainage-induced alterations in soil conditions can accelerate plant growth and biomass accumulation, with notable increases in aboveground biomass (AGB) reported in multiple studies. Drainage has been shown to facilitate shrub expansion and cover increase [36,93], while lichen biomass in drained hollows rises significantly, indicating shifts in vegetation composition [94]. Plots closer to drains also exhibit greater AGB, likely due to enhanced soil moisture and nutrient availability [39]. Conversely, other studies have shown contrasting results. A decline in the water table can lead to a significant reduction in shrub leaf mass (LM) and stem mass (SM) [143]. Synthesizing these findings reveals that the AGB trajectory is not uniform but governed by a combination of temporal dynamics and species-specific variability. The impact of drainage on AGB is time-dependent, following a successional pattern: in the first year, AGB declined markedly, especially in hygrophytes (e.g., sedges, cordgrasses), while mesophytes (e.g., graminoids, Asteraceae) were largely unaffected. By the second year, mesophyte gains offset wetland species losses, stabilizing AGB. In the third and fourth years; however, AGB increased substantially, driven mainly by mesophytes such as Anemone trullifolia var. linearis [95]. Thus, the apparent contradiction among studies can be resolved by considering each study’s timing relative to the disturbance: initial declines reflect the loss of hygrophytes, while subsequent increases signal the establishment and dominance of mesophytic species.

Belowground biomass (BGB) responses are inconsistent and equally context-dependent. This variability can be attributed to differences in species life forms, soil types, and drainage duration. Some studies report no significant changes, likely because peatland plants allocate a large proportion of their biomass to their roots (RM) and are resilient to short-term environmental fluctuations, or because mesophyte root gains offset wetland species losses [95]. In contrast, the fine root biomass (FRB) of trees was significantly higher in drained sites [143,146]. Yet, drainage reduced RM in peat substrates [146], while Salix nigra and Taxodium distichum exhibited higher RM under drainage compared with undrained sites [36]. This heterogeneity in BGB response underscores a high degree of species-specific variability, particularly between woody and herbaceous life forms. Crucially, the root–shoot ratio (RSR) serves as a key integrator of the plant carbon allocation strategy in response to water stress. The overall trend under drainage is a reduction in RSR, signaling a strategic shift from belowground resource foraging to aboveground competition for light as soil water becomes less limiting (Table S2). The magnitude of this change, however, varies among life forms. Shrubs in drained sites displayed a markedly lower RSR alongside higher stem mass [143], a response characteristic of woody plants that invest in vertical growth. In contrast, herbaceous plants exhibit a more variable response, often involving reductions in both RM and RSR, reflecting a diminished capacity for overall growth under new hydrological regimes [96,143].

Morphological traits also change markedly under drainage. Leaf area (LA) and leaf area index (LAI) generally decrease as water tables fall, reducing transpiration and conserving water [93,145]. Specific leaf area (SLA) decreases, while leaf thickness (LT) increases, indicating thicker, drought-tolerant leaves. SLA is closely linked to drainage conditions: higher SLA values prevail in nutrient-rich, drier habitats [137]. Stem diameter (SD) increases under drainage [36], whereas root diameter (RD) declines, reflecting a shift toward finer roots with lower construction costs [145]. Reports on root length (RL) are mixed: while some studies show RL increases under drier conditions [145], others report declines, such as reduced RL in Carex lasiocarpa [96] and Betula pubescens, but no change in Picea abies [146]. Specific root length (SRL) generally increases with drainage [145,146].

Plant height (H) responses are equally variable: some species (e.g., Taxodium distichum) grow taller under drained conditions [36,39], while others show reduced height [96]. The response of H to drainage can also be observed through changes in the mean, range, and variability of H in plant communities. Drainage conditions may result in a higher prevalence of shorter plants in the community, implying that the growth of taller plants may be restricted to some extent under drained conditions [137]. In swamp ecosystems, the cover, height, and density of reeds in degraded wetlands (often associated with drainage) show a significant decreasing trend. In sedge swamps, sedge growth is better in natural wetlands than in degraded (drained) swamps. These phenomena indicate that drainage activities have a significant negative impact on the height and overall growth of wetland vegetation, leading to reductions in vegetation cover and height [128].

Chemical traits reveal further complexity. Improved aeration and nitrogen mineralization under drainage increase leaf nitrogen content (LNC), reducing the leaf C:N ratio [155,162]. In some cases, higher LNC coincides with stable leaf phosphorus content (LPC), raising the leaf N:P ratio [159]. Conversely, shrub leaves may exhibit reduced C:P ratios due to enhanced phosphorus uptake [163]. Root carbon content (RCC) often remains unchanged, while root nitrogen content (RNC) exhibits dynamic patterns: peaking under short-term drainage and fluctuating under long-term drainage, reflecting adaptive adjustments in nitrogen allocation and water-use efficiency [145].

In terms of physiological traits, as the water table declines, stomatal conductance (Gs) gradually decreases. This is a defensive mechanism employed by plants to reduce water evaporation by closing stomata, thereby minimizing water exchange between leaves and the external environment. However, this protective response also blocks the exchange pathway for external carbon dioxide (CO2) to enter the plant, resulting in a decrease in the net photosynthetic rate (Pn) [145]. Photosynthetic efficiency (closely related to Pn) decreases progressively with a falling water table, mainly due to insufficient CO2 supply caused by reduced Gs. Plants may also inhibit carboxylase activity under water stress, further affecting photosynthesis. Additionally, to maintain photosynthesis, plants may increase intercellular CO2 concentration as a compensatory mechanism to alleviate CO2 limitation [145].

4.2. Vegetation Removal

Vegetation removal refers to the loss, damage, or elimination of wetland vegetation due to human activities. These activities primarily include grazing, mowing, deforestation, and large-scale land clearing, among which grazing and mowing have been the focus of most ecological studies due to their direct and frequent impacts on wetland plant communities. Specifically, grazing is the foraging behavior of domestic animals (e.g., cattle, sheep) in wetland areas; such animals directly consume vegetation and deplete plant biomass. Mowing refers to the cutting of herbaceous or woody plants in wetlands using mechanical equipment (such as mowers) or manual tools, altering the structure and growth cycle of plant communities.

Aboveground biomass (AGB), a key indicator of wetland primary productivity and carbon storage capacity, is significantly affected by vegetation removal, especially grazing. Numerous studies have consistently shown that grazing substantially reduces AGB [54,84,89,102]. As grazing intensity increases, the total biomass (TB) and AGB of the entire plant community decrease remarkably, and this reduction is particularly pronounced in heavily grazed areas [81]. For example, in swampy wetland areas, heavy grazing can reduce AGB to almost one-third of that in ungrazed areas [88]. This substantial AGB loss not only translates to reduced primary productivity but also means that the wetland’s carbon storage capacity is significantly impaired, potentially transforming these ecosystems from carbon sinks to carbon sources over time. In contrast, the AGB of wetlands in highly managed rangelands is generally higher than that of semi-natural rangelands [80], and across different wetland types, ungrazed areas consistently have significantly higher AGB than grazed areas [82]. Mowing also decreases AGB, particularly when frequent or intensive [30], though light mowing often has negligible effects [35].

Belowground biomass (BGB) plays a vital role in nutrient uptake, soil organic carbon accumulation, and wetland ecosystem stability. BGB is also affected by grazing, but the effect is less significant than that on AGB [84,102]. Nevertheless, in heavily grazed areas, especially in wet grasslands and swampy areas, BGB can be reduced by 2.5 and 3.5 times, respectively, compared to ungrazed areas [88]. Such a pronounced reduction in BGB compromises multiple ecosystem functions: it weakens soil stabilization, reduces organic matter input to soils, and impairs nutrient cycling processes, thereby threatening the long-term stability of wetland ecosystems. Interestingly, although the BGB in ungrazed areas is generally larger, the overall difference in BGB between grazed and ungrazed salt marshes is not significant [82], suggesting that the BGB response to grazing may be influenced by the wetland type.

Stem mass (SM), an important indicator of plant community roughness and structural support, is suppressed by grazing. Grazing tends to select forbs and reduce plant height (H), resulting in a low, uniform herbaceous cover, which may lead to a reduction in SM [133]. This reduction in SM further exacerbates the loss of structural diversity in wetland plant communities, diminishing their capacity to provide habitat complexity and physical protection for soil surfaces.

Plant height (H), a critical trait affecting light capture, aboveground competition, and the ability of emergent species to survive flooding, is significantly influenced by vegetation removal. Ungrazed areas consistently have a significantly higher H than grazed areas, indicating that grazing reduces plant height [82,128]. For example, long-term grazing significantly affects the H of Salix lapponum, with the average H being significantly higher in areas without summer grazing compared to those with summer grazing [166]. Grazing also has species-specific effects on H: it significantly reduces the H of A. plantago-aquatica, Polygonum spp., and S. latifolia but significantly increases that of P. amplifolius, and while it has a significant positive effect on the H of Eleocharis obtusa, Leersia oryzoides, and Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani, it exerts a significant negative effect on that of Erechtites hieracifolius [84]. In some cases, grazing may increase H, while in others, mowing may favor H maintenance or reduction [126], reflecting the complexity of H responses to different vegetation removal disturbances. Mowing also affects plant height. For D. muscoides and O. andina, H is lower under mowed conditions than under uncut conditions [132]. The cessation of mowing leads to an increase in H [78], and the H of Phragmites australis decreases as mowing intensity increases [134]. Additionally, H decreases significantly with increasing grazing intensity [89], and the stem diameter (SD) of reeds decreases with increased grazing intensity [134].

Specific leaf area (SLA), a trait related to light capture efficiency, relative growth rate, and photosynthetic capacity, is affected by both grazing and mowing. Grazing significantly increases the community-weighted mean SLA (CWM-SLA), suggesting that under grazing pressure, plants may improve their tolerance by increasing SLA [110]. The use of tracked mowers also leads to an increase in the SLA of wetland plant communities [153]. For species such as J. maritimus, E. atherica, and F. rubra, SLA increases under grazing conditions, indicating that these plants may experience improved growth conditions or adopt an adaptive strategy to cope with grazing disturbance [79]. However, the direction and magnitude of SLA response are not uniform and appear to be mediated by several factors. The seemingly contradictory data across studies may stem from differences in (i) species-specific strategies, where some plants inherently adopt acquisitive (high-SLA) versus conservative (low-SLA) resource-use strategies; (ii) grazing pressure intensity, as moderate grazing might favor high-SLA species through nutrient input and reduced competition, while intense grazing could overall reduce SLA due to chronic stress; and (iii) wetland-specific conditions, such as nutrient and water availability, which can constrain or facilitate plastic trait shifts. Therefore, the reported increase in community-level SLA likely reflects a combined outcome of species turnover towards more acquisitive strategists and phenotypic plasticity within species, modulated by local grazing regimes and wetland types.

Leaf area (LA) and leaf area index (LAI), which are crucial for photosynthesis, transpiration, and energy exchange in plants, show variable responses to vegetation removal. Some studies have found that LA does not differ significantly between grazing treatments [129,135], while others suggest that grazing may reduce LA, including LAI [90]. Mowing has no significant effect on LAI [35], possibly due to the rapid regrowth of leaves after mowing, offsetting the reduction in leaf area.

Specific root length (SRL), a trait that reflects the efficiency of root nutrient and water uptake, does not change significantly with grazing treatments [79,110], indicating that grazing has little impact on the root foraging efficiency of wetland plants.

Total nitrogen content (TNC), which includes leaf nitrogen content (LNC) and root nitrogen content (RNC) and is essential for plant photosynthesis, growth, and reproduction, may be reduced by grazing [54]. Specifically, LNC and stem nitrogen content (SNC) are lower in grazed areas than in ungrazed areas, while leaf carbon content (LCC) and stem carbon content (SCC) are higher in grazed areas [102]. This shift in carbon and nitrogen content may affect the nutritional quality of plants, thereby influencing the structure and function of the aboveground food web in wetland ecosystems.

4.3. Invasive Alien Species

Invasive alien species (IAS) pose a major threat to the structural and functional integrity of wetland ecosystems, primarily by modifying the functional traits of native plants. Over the past two decades, studies worldwide have consistently shown that IAS invasions alter the biomass allocation, morphological structures, chemical composition, and physiological processes of native species, though the magnitude and direction of the effects vary depending on the species, invasion intensity, and environmental context.

From the perspective of the Plant Economics Spectrum, IAS typically exhibit acquisitive traits (high specific leaf area, high leaf nitrogen content) that enable rapid resource capture, giving them a competitive advantage over native species with more conservative traits [152]. This aligns with Grime’s CSR model, where IAS often function as “Competitors” or “Ruderals” by outcompeting natives for light, nutrients, and water, or colonizing disturbed habitats rapidly [167].

Native above- and belowground biomass (AGB, BGB) is often suppressed by IAS competition. For example, the AGB of native Spartina alterniflora declines sharply when competing with alien S. anglica, with concurrent reductions in BGB and root traits [73]. Similarly, Zostera japonica experiences sustained AGB loss following invasion by S. alterniflora [72], while severe invasions reduce biomass in Hydrilla verticillata and Myriophyllum verticillatum [103]. Yet, in some cases, IAS increase total community biomass due to their own high productivity—for instance, Fallopia japonica reduces diversity but elevates total biomass (TB) [76], and Solidago gigantea enhances ecosystem AGB [168]. Phragmites australis invasions also significantly raise AGB under diverse hydrological regimes [19,71].

Biomass allocation strategies further differentiate IAS from natives. Invasive Phragmites australis has a significantly higher root–shoot ratio (RSR) than native Spartina maritima, indicating greater investment in underground organs to enhance resource uptake [169]. Invasive Spartina alterniflora also allocates more biomass to its roots, as evidenced by its higher root mass ratio (RMR) compared to native Phragmites australis [170], and its root mass (RM) is significantly greater than that of native Scirpus mariqueter and Phragmites australis—a trait linked to increased carbon storage and competitive resource capture [171].

Plant height (H), a key trait for light competition and flood tolerance, is commonly modified by IAS. Helianthus tuberosus and Mediterranean Phragmites australis (M1 lineage) grow taller in introduced areas, with the latter also producing more shoots—adaptations that facilitate rapid colonization [124,167]. For native species, however, H is often suppressed: Phragmites australis invasion reduces the H of native plants [71] and the height of nutrient and reproductive branches [72].

Leaf and stem morphological traits further mediate invasion success. Invasive Wedelia trilobata has significantly higher leaf area (LA) and specific leaf area (SLA) than native Wedelia chinensis at low water depths—traits that enhance light capture and contribute to its wetland invasion success [19]. Similarly, invasive M. intermedia in introduced sites exhibits larger LA and SLA (but lower leaf thickness (LT)) than in its native range, supporting the “evolutionary increase in competitiveness” hypothesis [172]. In mixed communities, invasive Spartina alterniflora achieves a higher LAI than native Scirpus mariqueter and Phragmites australis, maximizing light absorption for photosynthesis [171]. Compared with native mangroves, exotic mangrove species also have higher SLA, a trait associated with faster growth rates [152].

Often acting as ecosystem engineers, IAS cause alterations to stem and root traits that can fundamentally shift wetland ecosystem structure and function. The stem traits of IAS further reinforce their advantage: invasive Spartina alterniflora has higher stem density than native Phragmites australis and Cyperus malaccensis [173]. This structural change enhances sediment trapping and accretion rates, which can gradually elevate the wetland platform and modify topography over time—a key biogeomorphic process. Similarly, Helianthus tuberosus exhibits higher stem density in invaded sites—thereby altering community structure and reducing native species richness [123]. At the root level, Phragmites australis invasion reduces the root length (RL) and stem diameter (SD) of native plants [71]. This root trait disruption weakens the soil-binding capacity of the plant community, compromising sediment stabilization and increasing the ecosystem’s vulnerability to erosion. Collectively, these trait-mediated impacts can reconfigure wetland landscapes, influencing critical ecosystem services such as coastal protection, carbon sequestration dynamics, and the habitat template for associated biota.

IAS invasions alter the carbon (C), N, and phosphorus (P) composition of wetland plants, with cascading effects on nutrient cycling. Invasive plants often exhibit higher leaf nitrogen content (LNC) than natives [75], suggesting greater photosynthetic potential [19]. Exotic aquatic plants also have higher LNC than native mangroves [75]. A comparative study of 41 woody species in New Zealand found that alien species consistently have higher LNC and leaf N:P ratios but lower leaf C:N ratios—traits linked to efficient nutrient use [174].

Chlorophyll content (CT), a proxy for photosynthetic capacity, is sensitive to IAS invasions. Native Mediterranean Phragmites australis (M1 lineage) produces more new shoots and has significantly higher CT than introduced conspecifics, indicating enhanced photosynthetic performance in native ranges [124]. However, Phragmites australis also releases root exudates that act as chemosensitizers, reducing CT in native plants and potentially inhibiting their photosynthesis [71].

IAS impacts on nutrient cycling extend beyond plant tissues: AGB C and N stocks are positively correlated with invasive species biomass, indicating that invaders modulate ecosystem C and N cycling [175]. Most belowground root C, N, and P in invaded wetlands are stored in topsoil layers, with concentrations decreasing with soil depth—highlighting the role of IAS in reshaping soil nutrient pools [173].

4.4. Nutrient Enrichment and Fertilization

Eutrophication, a pervasive anthropogenic disturbance, profoundly influences wetland plant functional traits, with effects varying by trait type, species identity, and nutrient regime. Across ecosystems, aboveground biomass (AGB) generally increases under nutrient enrichment, although responses depend on nutrient type and concentration. Graminoids such as Carex spp. and shrubs in peatlands exhibit marked AGB gains under combined NPK addition [27,47]. Herbaceous taxa such as Typha and Eleocharis also benefit, whereas others (e.g., Cladium) remain unresponsive [48]. Woody species, including Taxodium distichum, show steady growth under elevated N [64]. However, excessive N may suppress AGB by exacerbating flooding stress or exceeding nutrient thresholds [45,66].

Notably, invasive alien species (IAS) often benefit more from eutrophication than their native counterparts. In eutrophic environments, invasive Phragmites australis produces significantly higher AGB than native conspecifics [60]. In Willapa Bay and San Francisco Bay estuaries, N fertilization markedly increases the AGB of invasive Spartina alterniflora, while the same eutrophic conditions suppress the AGB of native Phragmites australis [44,147]. This competitive advantage of IAS may stem from higher phenotypic plasticity—for example, invasive Wedelia trilobata exhibits higher leaf mass (LM) and stem mass (SM) under high nutrients than native Wedelia chinensis, enabling it to outcompete native species [107].

Belowground biomass (BGB) responses to eutrophication are more variable, driven by nutrient type, concentration, and environmental context. Nitrogen addition increases the BGB of Juncus effusus and both invasive and native Phragmites australis [38,111,176], and eutrophication promotes root growth in Typha and Eleocharis [48]. However, excess nutrients can inhibit BGB: high N loading reduces BGB in tidal marsh grasses (Spartina patens and Distichlis spicata), particularly under high inundation [31,67], and P addition also suppresses BGB [17]. Higher N concentrations further inhibit root elongation, indirectly lowering BGB [21]. Additionally, BGB responses may saturate at high nutrient levels for some species [47], and the magnitude of BGB change is generally smaller than that of AGB [53].

Eutrophication also reshapes biomass allocation between aboveground and belowground organs, as well as among leaves, stems, and roots. For aboveground components, eutrophication increases stem mass (SM) in species such as Avicennia germinans, Spartina alterniflora, Spartina patens, and Distichlis spicata—for example, A. germinans allocates less biomass to leaf mass (LM) and more to SM when nutrient limitation is alleviated [69,115]. High nutrient levels further elevate the dry matter content (DMC) of whole plants [119], as well as the leaf mass ratio (LMR) and stem mass ratio (SMR) [57,62].

The root-to-shoot ratio (RSR) typically decreases with fertilization, as the relative increase in AGB outpaces that in BGB [61]. However, a growing body of evidence suggests that this response is not universal and can be modulated by species-specific strategies and environmental contexts. While high nutrient levels typically reduce the RSR by favoring aboveground growth [47], several notable exceptions highlight the complexity of this trait’s response. For instance, contrary to the common pattern, native Wedelia chinensis has a higher RSR under low nutrients, but invasive Wedelia trilobata exhibits an elevated RSR under high nutrients and inundation, a strategy thought to enhance its competitive ability in eutrophic habitats [107]. Furthermore, a global meta-analysis by Li et al. (2016) demonstrated that the negative effect of N enrichment on the RSR is significantly weaker in woody plants than in herbaceous species, underscoring that the plant life form is a critical factor influencing biomass partitioning under eutrophication [177]. Beyond overall biomass allocation, eutrophication also induces structural changes in root systems: nutrient-enriched plants often produce more fine roots to enhance nutrient foraging, whereas non-enriched plants allocate more biomass to thick roots and rhizomes, which are critical for long-term resource storage and organic matter accumulation [50]. Increased N availability further drives a relative AGB increase—by accelerating aboveground growth faster than belowground growth—thereby raising the RSR [17,53]. In summary, while the overarching pattern of RSR reduction under eutrophication is well-established, emerging research underscores the importance of considering phylogenetic and ecological contexts, such as species identity, invasive status, and life form, to fully understand the nuances of plant adaptive strategies.

Plant height responses are species- and ecosystem-specific. In peatlands, eutrophication promotes shrub height and stem density [27], and high-N addition generally increases vegetation height [118]. Most invasive and native species exhibit height increments under eutrophication: for example, Alternanthera philoxeroides, Phragmites australis, Juncus effusus, and Spartina alterniflora grow taller with increasing N concentrations [37,56,112], and moderate-N addition optimizes Phragmites australis height [114]. Phosphorus addition also stimulates height growth in Eleocharis, particularly in the first post-fertilization growing season [55]. Conversely, some species exhibit height reductions under eutrophication. In herbaceous marshes, high N concentrations suppress the height and growth rate of Carex schmidtii [108], and Spartina alterniflora height decreases with increasing N loading [65]. Additionally, eutrophication may have no effect on height—for example, no significant change in tree height was observed at the Whangapoua study site [121]. These variations highlight that height responses depend on the interplay of species identity, nutrient type, and environmental conditions (e.g., flooding).

Leaf dry matter content (LDMC) and leaf tissue density (LTD) typically decrease with eutrophication, reflecting reduced tissue robustness in nutrient-rich environments. Nitrogen and P treatments significantly lower LDMC [45], and high-N addition further reduces the LDMC of Juncus effusus [56] and Phragmites australis [105]—a trend linked to decreased LTD under high nutrients [118]. Excess N and P also alter leaf shape: Carex schmidtii exhibits changes in aspect ratio (leaf length (LL)/leaf width (LW)) under high N and P [108]. In contrast, leaf thickness (LT) may increase under eutrophication: LT correlates positively with total phosphorus and suspended solids in water, suggesting that thicker leaves are an adaptation to eutrophic conditions [151].

Eutrophication induces significant alterations in plant morphological traits, including plant height (H), leaf morphology (e.g., leaf area (LA), specific leaf area (SLA)), and stem characteristics (e.g., stem density, stem count), with these changes closely linked to resource acquisition (e.g., light capture) and competitive ability. Leaf morphological traits are strongly influenced by eutrophication, with most changes enhancing photosynthetic efficiency. LA generally increases under high nutrients: N addition boosts the LA of Phragmites australis and Alternanthera philoxeroides [37,112], and the LA of nitrogen-fertilized dwarf mangroves doubled in two years [121].

Specific leaf area (SLA), a key indicator of light capture and growth strategy, exhibits mixed responses to eutrophication. Most species, including Avicennia germinans, Alternanthera philoxeroides, and invasive Wedelia trilobata, show increased SLA under high nutrients—this change enhances photosynthetic efficiency by maximizing leaf area per unit mass [37,57,115]. However, SLA may decrease under certain conditions: excess N and P reduce the SLA of Carex schmidtii [108], and while N addition increases the leaf area (LA) of Phragmites australis, it causes a slight SLA decline—possibly due to increased leaf thickness (LT) or higher leaf mass (LM) per unit area [112]. Aquatic plants also show reduced SLA under eutrophication-induced environmental stress [151].

Stem morphological traits, including stem density and stem count, are modulated by eutrophication in a species-specific manner. Nitrogen fertilization increases the stem density of Spartina acutus, Spartina alterniflora, and invasive Spartina alterniflora in estuaries [17,33,44], while P addition enhances the stem density of Eleocharis [55]. Stem count also rises under high N [50,56], and Spartina alterniflora has a higher stem density in salt marshes with elevated N loads [65]. However, eutrophication reduces the stem density of some species: Phragmites australis shows a lower stem density under both N-enriched and non-enriched conditions [41], and Spartina alterniflora, Spartina patens, and Distichlis spicata exhibit a reduced stem density in eutrophic environments [69]. For tall Spartina alterniflora in low marshes, stem density remains unchanged, while some populations show interannual declines [69]. These patterns indicate that stem trait responses depend on nutrient availability, species life history, and environmental context.

Root morphological traits are shaped by both fertilization and hydrology. Root diameter (RD) increases under high-water conditions, but fertilization reduces RD in Deyeuxia angustifolia under such conditions [30]. Specific root length (SRL) responses vary among species: Carex lasiocarpa shows higher SRL under low water and low nutrient availability, while Glyceria spiculosa exhibits increased SRL under high water; Deyeuxia angustifolia deviates from both, with SRL responses uncoupled from these patterns [30]. Root length (RL) decreases with increasing N concentration at 5 cm and 15 cm flooding depths, highlighting the interactive effects of nutrient supply and flooding [29].

Eutrophication profoundly alters plant chemical traits (e.g., nutrient content, C:N:P ratios) and physiological traits (e.g., chlorophyll content (CT)), with these changes influencing photosynthesis, nutrient use efficiency, and ecological competitiveness.

Leaf nitrogen content (LNC) is consistently elevated under eutrophication, as increased N availability enhances plant N uptake and transport. The LNC of Alternanthera philoxeroides, Spartina alterniflora, and mangroves increases with N addition [37,69,141], and LNC saturates at high N concentrations [45]. Eutrophic wetlands also have higher average N content in stems and roots than natural wetlands, with elevated leaf N:P and stem N:P ratios [159]. However, species-specific differences exist: the LNC of aquatic plants decreases under eutrophication-induced stress [151], and excess N may reduce leaf phosphorus content (LPC) by limiting P uptake [114]. High nutrient levels increase root phosphorus content (RPC) and stem phosphorus content (SPC) but have no significant effect on LPC [119], while P addition specifically boosts tissue P content of Eleocharis [55].

Leaf C:N:P ratios, which are key indicators of nutrient-use efficiency, are reshaped by eutrophication. Leaf C:N and C:P ratios generally decrease under high nutrients: N addition lowers C:N in the aboveground parts and roots of Juncus effusus [111], and eutrophication reduces the leaf C:N and C:P of wetland plants [46]—reflecting enhanced N and P utilization. Leaf N:P ratios increase with water column N concentrations, as plants take up more N and P under eutrophication [32,63]. However, exceptions occur: leaf C:N may increase in water bodies with high P and organic C [116], highlighting the role of nutrient co-limitation.

Chlorophyll content (CT), a proxy for photosynthetic capacity, shows species-specific responses to eutrophication. Wedelia trilobata and Alternanthera philoxeroides have higher CT under high nutrients, enhancing their photosynthetic efficiency and competitiveness [37,104]. For Phragmites australis, CT initially increases with N addition but declines under excess N [105]—indicating a nutrient threshold for optimal photosynthesis. In contrast, Carex schmidtii exhibits reduced CT under N and P treatments [45], and combined N+P addition lowers CT to levels similar to those observed with N alone [108]—suggesting that multi-nutrient enrichment may disrupt chlorophyll synthesis. These variations reflect differences in species tolerance to nutrient overload and highlight the complexity of physiological responses to eutrophication.

4.5. Others

The aboveground biomass (AGB) and belowground biomass (BGB) of mangrove forests are relatively high in protected areas and in the vicinity of tidal channels, while they are significantly lower in urbanized and timber development areas. In addition, anthropogenic disturbances, especially agricultural activities, deforestation, and human settlement, have significantly reduced the aboveground biomass of peatlands [97]. Logging activities have likewise led to a significant decrease in the total aboveground biomass of forests [99]. The AGB of the invasive Phalaris arundinacea decreased during urbanization, especially in plants treated with urban pollutants such as salt, copper, and zinc [98]. Anthropogenic disturbances in these areas have resulted in a decrease in stem density and an increase in the proportion of biomass in the small-stem-diameter class. Meanwhile, leaf area (LA) was positively correlated with AGB, suggesting that LA is an important indicator of productivity, but anthropogenic activities have increased its variability [74]. Anthropogenic disturbance had a significant positive effect on the specific leaf area (SLA) of deciduous species, suggesting that disturbance may have promoted leaf growth and expansion in deciduous species [138]. Urbanization also increased SLA, leading to a reduction in the area of rice paddies in the Qinhuai River basin, which in turn induced a significant decrease in LA [150]. In the studied forests, LA generally declined after logging [99]. In terms of tree height, anthropogenic disturbance had a significant positive effect on the height of deciduous tree species (p < 0.05); i.e., in areas with higher levels of disturbance, deciduous tree species had higher mean tree heights [138]. However, urbanization led to a reduction in the plant height (PH) of invasive Phalaris arundinacea [98]. Additionally, urbanization has resulted in a significant decrease in chlorophyll content and a decrease in H [98]. Belowground dry biomass was also significantly reduced by urbanization. Root–shoot ratios of invasive Phalaris arundinacea increased in areas of high urbanization intensity, suggesting that plants may be adapting to urban environments by increasing their root systems [98].

5. Summary and Future Prospects

This study revealed the far-reaching impacts of human activities on wetland ecosystems, especially on plant functional traits. Our synthesis demonstrates that anthropogenic disturbances act as environmental filters, selecting for trait combinations that align with established ecological theories. For instance, drainage and nutrient enrichment often shift communities towards more acquisitive strategies (high SLA, low LDMC) as predicted by the Plant Economics Spectrum, while intense vegetation removal can favor conservative traits. The pervasive success of invasive species under eutrophication often reflects a highly acquisitive, competitive (C-strategist) phenotype, consistent with Grime’s CSR model. Different types of disturbances, such as drainage, fertilization, invasive exotic species, mowing and grazing, and urbanization, had significant impacts on wetland ecosystems. These disturbances not only changed the aboveground (AGB) and belowground biomass (BGB) of wetland plants but also affected plant height (H), root-to-shoot ratio (RSR), leaf nitrogen content (LNC), leaf carbon content (LCC), and other traits—with responses coordinated along the Plant Economics Spectrum and consistent with Grime’s CSR model. For example, nutrient enrichment and IAS invasion favor acquisitive traits (high SLA, LNC), while drainage and heavy grazing select for conservative traits (high LDMC, root mass ratio) or Ruderal strategies (rapid regrowth). The synthesis of biomass responses provides clear conservation implications with quantitative reference thresholds: A decline in AGB of >30% in hygrophytic herbs (e.g., sedges) indicates severe drainage stress, requiring hydrological restoration to raise water tables by 10–20 cm. Conversely, AGB increases of >50% driven by IAS (e.g., Spartina alterniflora) signal high invasion pressure, necessitating control measures to reduce invader cover below 20% of the community. Furthermore, grazing-induced AGB reductions of <20% are manageable, but reductions exceeding 40% (e.g., in swampy wetlands) require grazing exclusion for 2–3 growing seasons to recover. These thresholds are derived from the quantitative summary of 166 studies (Supplementary Table S2) and provide practical benchmarks for management. The context-dependent biomass shifts in response to grazing and fertilization highlight that management actions, such as adjusting grazing intensity or fertilizer use, must be tailored to specific wetland types and plant communities to achieve desired conservation outcomes. This trait-based, theoretically grounded understanding moves beyond descriptive summaries to provide a predictive framework for how wetland plant communities are likely to respond to human pressures.

Drainage disturbances mainly affected marshy wetlands, with the biomass of wet and herbaceous plants decreasing and that of mesophytes and trees increasing; mowing was more common in marshy wetlands and coastal wetlands and usually elevated the aboveground biomass of wetlands, positively affecting leaf area (LA), specific leaf area (SLA), and LNC but decreasing H and leaf dry matter content (LDMC). The effects of grazing on wetland plants were more complicated, resulting in reduced AGB and H, but negatively affecting the AGB of specific species, such as alpine goosegrass and red fescue, while changes in SLA and LDMC varied by wetland type. Invasive exotic species had particularly significant impacts on wetland ecosystems, with exotics typically having greater survival and competitive abilities; some invasive species (e.g., Miscanthus auriculatus) were found to have higher AGB at medium and high tidal levels, and others (e.g., M. intermedia) had significantly higher AGB than native species. Leaf N and C concentrations of invasive species differed from those of native species, possibly affecting photosynthesis and tissue decomposition rates. In addition, anthropogenic eutrophication of water and soil exacerbates the instability of wetland ecosystems and promotes the invasion of invasive species, which in turn affects the growth of native plants. The effects of fertilizer application, a common human activity leading to wetland eutrophication, depend on the amount and type of fertilizer applied. Moderate fertilization can increase above- and belowground biomass, while excessive use of mineral fertilizers may lead to a biomass reduction. Fertilization also alters leaf morphology and physiological characteristics (e.g., increased LA and chlorophyll content) and affects leaf N and C content and the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio; other types of disturbances, such as urbanization and tree felling, are less well-studied, but their destructive power should not be ignored; studying these factors and the damage they cause could reveal significant indicators of a variety of wetland plants’ traits.

Building on these findings, our synthesis offers concrete implications for wetland management and conservation. Several functional traits emerged as highly sensitive and practical indicators, useful for monitoring wetland degradation and guiding restoration. AGB and H are robust, integrative indicators for assessing overall ecosystem productivity and structural changes in response to disturbances such as nutrient enrichment and vegetation removal. The RSR serves as a key diagnostic tool for understanding carbon allocation shifts under drainage and water stress. For evaluating leaf-level resource-use strategies, SLA and LDMC are highly responsive to nutrient enrichment and grazing, while LNC provides direct insight into a plant’s nutrient acquisition status. In practical applications, monitoring these trait combinations can help managers set specific restoration targets. For instance, in a drained wetland, an increase in the RSR and a decrease in H in key species could signal successful re-establishment of hydrological stress regimes. Similarly, in overgrazed areas, recovery of LDMC and AGB can be tracked to objectively evaluate the effectiveness of grazing exclusion. Furthermore, selecting plant species with appropriate trait values (e.g., high LDMC for stress tolerance, or competitive traits such as high SLA for rapid site occupancy) can be a strategic approach to designing resilient plant communities in restoration projects.

While the vote-counting method employed here allowed for a broad synthesis across a highly heterogeneous body of literature, we acknowledge the limitations regarding the inability to calculate effect sizes or conduct formal meta-analysis. The extreme variability in data reporting (e.g., units, experimental designs) across the 166 global studies made a quantitative meta-analysis unfeasible for this initial, comprehensive review. Future research efforts would greatly benefit from the development of a standardized global database for plant trait responses to disturbance. Such a resource would enable rigorous meta-analyses to quantify effect sizes, assess publication bias, and more powerfully test the theoretical patterns identified in this review. Furthermore, integrating geospatial data on disturbance intensity with trait responses could help move beyond qualitative summaries towards establishing quantitative thresholds for management.

Furthermore, the pronounced geographical bias in study sites—concentrated in Asia, Europe, and North America—may reflect the spatial distribution of both anthropogenic pressures and specific wetland types. Regions with intensive human activities (e.g., agricultural drainage in temperate fens, urbanization pressures, or well-documented invasive species) naturally attract more research focus on trait-based responses. Conversely, the underrepresentation of Africa, Central America, and Oceania limits our understanding of how wetland plants from diverse biogeographic contexts (e.g., tropical peatlands or arid-zone wetlands), which may host unique trait combinations, respond to dominant local disturbances such as different grazing regimes or water extraction. This geographical knowledge gap hinders a comprehensive understanding of global wetland functional ecology. Future studies should therefore target these understudied regions and disturbance contexts to discern whether general patterns in trait–disturbance relationships exist, or whether they are contingent on specific wetland plant assemblages and anthropogenic stressor regimes.

Future research should also delve into the molecular mechanisms of the effects of different disturbance types on wetland plant traits and explore how changes to these traits affect plant adaptations and ecosystem service functions. Comparative studies across ecosystems are warranted to better understand how different wetland types vary in their response to disturbances. Further research should explore the resilience and adaptability of wetland ecosystems to disturbances and examine ecological engineering and management practices that may enhance their resilience. In addition, the impacts of urbanization and other emerging disturbance types on wetland ecosystems need to be studied to develop effective conservation strategies. Finally, future research should consider the potential impacts of climate change on wetland ecosystems and analyze how these impacts interact with those of human activities.

Through these efforts, we can advance our understanding of human impacts on wetland ecosystems and strengthen the scientific basis for their conservation and restoration.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ecologies6040085/s1, Table S1: List of literature used for this review identifying functional traits responses to various anthropogenic disturbance types; Table S2: Response summaries of the most commonly measured functional traits, including their definition, key role in plant functioning, and observed direction and frequency of response to anthropogenic disturbance; Figure S1: PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the process of study selection for this review.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L.; methodology, J.W. and C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.; writing—review and editing, C.L. and Z.L.; supervision, C.P. and B.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 42201114 and U22A20570, and the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 2021JJ40338, 2024JJ5265, and 2025JJ80282.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kundu, S.; Kundu, B.; Rana, N.K.; Mahato, S. Wetland Degradation and Its Impacts on Livelihoods and Sustainable Development Goals: An Overview. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 48, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, K.A.; Ritchie, M.E. Effects of Macrophyte Species Richness on Wetland Ecosystem Functioning and Services. Nature 2001, 411, 687–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloey, T.M.; Ellis, V.S.; Kettenring, K.M. Using Plant Functional Traits to Inform Wetland Restoration. Wetlands 2023, 43, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, E.J. Wetlands Under Global Change. In Encyclopedia of Inland Waters; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Prentice, I.C. Global Patterns of Plant Functional Traits and Their Relationships to Climate. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Sanchez-Gomez, D.; Zavala, M.A. Quantitative Estimation of Phenotypic Plasticity: Bridging the Gap between the Evolutionary Concept and Its Ecological Applications. J. Ecol. 2006, 94, 1103–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio-López, K.; Beckage, B.; Scheiner, S.; Molofsky, J. The Ubiquity of Phenotypic Plasticity in Plants: A Synthesis. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 3389–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Barougy, R.F.; Elgamal, I.A.; Khedr, A.-H.A.; Bersier, L.-F. Contrasting Alien Effects on Native Diversity along Biotic and Abiotic Gradients in an Arid Protected Area. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Du, Y.; Liu, X.; Wan, X.; Yin, B.; Hao, Y.; Wang, Y. Grassland Biodiversity Response to Livestock Grazing, Productivity, and Climate Varies across Biome Components and Diversity Measurements. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 162994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.H. Eutrophication of Freshwater and Coastal Marine Ecosystems: A Global Problem. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2003, 10, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, A.S.; McCann, K.S.; Gellner, G.; Turkington, R. Diversity Loss with Persistent Human Disturbance Increases Vulnerability to Ecosystem Collapse. Nature 2013, 494, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.; Icely, J.; Cristina, S.; Perillo, G.M.E.; Turner, R.E.; Ashan, D.; Cragg, S.; Luo, Y.; Tu, C.; Li, Y.; et al. Anthropogenic, Direct Pressures on Coastal Wetlands. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomnicky, G.A.; Herlihy, A.T.; Kaufmann, P.R. Quantifying the Extent of Human Disturbance Activities and Anthropogenic Stressors in Wetlands across the Conterminous United States: Results from the National Wetland Condition Assessment. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.A.; Armitage, A.R. Above- and Belowground Responses to Nutrient Enrichment within a Marsh-Mangrove Ecotone. Estuar. Coast. SHELF Sci. 2020, 243, 106884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshaies, A.; Boudreau, S.; Harper, K.A. Assisted Revegetation in a Subarctic Environment: Effects of Fertilization on the Performance of Three Indigenous Plant Species. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2009, 41, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belowground Biomass of Spartina alterniflora: Seasonal Variability and Response to Nutrients. Available online: https://webofscience.clarivate.cn/wos/alldb/full-record/PQDT:61517268 (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Darby, F.A.; Turner, R.E. Below- and Aboveground Biomass of Spartina alterniflora Response to Nutrient Addition in a Louisiana Salt Marsh. Estuaries Coasts 2008, 31, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenihan, W.; Schultz, R. Carnivorous Pitcher Plant Species (Sarracenia purpurea) Increases Root Growth in Response to Nitrogen Addition. Botany 2014, 92, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, Q.; Sun, J.; Azeem, A.; Jabran, K.; Du, D. Competitive Ability and Plasticity of Wedelia trilobata (L.) under Wetland Hydrological Variations. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cebrián-Piqueras, M.A.; Trinogga, J.; Trenkamp, A.; Minden, V.; Maier, M.; Mantilla-Contreras, J. Digging into the Roots: Understanding Direct and Indirect Drivers of Ecosystem Service Trade-Offs in Coastal Grasslands via Plant Functional Traits. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, B.; Xie, T.; Wang, Q.; Yan, J. Effect of Coastal Eutrophication on Growth and Physiology of Spartina alterniflora Loisel. Phys. Chem. Earth 2018, 103, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, F.A.; Turner, R.E. Effects of Eutrophication on Salt Marsh Root and Rhizome Biomass Accumulation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 363, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Song, C.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y. Effects of Exogenous Nitrogen on Freshwater Marsh Plant Growth and N2O Fluxes in Sanjiang Plain, Northeast China. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ket, W.A.; Schubauer-Berigan, J.P.; Craft, C.B. Effects of Five Years of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Additions on a Zizaniopsis Miliacea Tidal Freshwater Marsh. Aquat. Bot. 2011, 95, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, J.W.; Schleicher, T.; Craft, C. Effects of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Additions on Primary Production and Invertebrate Densities in a Georgia (Usa) Tidal Freshwater Marsh. Wetlands 2009, 29, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effects of Nutrient Addition on Plant Community Composition: A Functional Trait Analysis in a Long-Term Experiment-All Databases. Available online: https://webofscience.clarivate.cn/wos/alldb/full-record/PQDT:60652620 (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Bubier, J.L.; Moore, T.R.; Bledzki, L.A. Effects of Nutrient Addition on Vegetation and Carbon Cycling in an Ombrotrophic Bog. Glob. Change Biol. 2007, 13, 1168–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, A.; Morris, N.M.B.; Lafabrie, C.; Cebrian, J. Effects of Nutrient Enrichment on Distichlis Spicata and Salicornia Bigelovii in a Marsh Salt Pan. Wetlands 2008, 28, 760–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Tang, H.; Chen, F.; Lou, Y. Functional Traits Response to Flooding Depth and Nitrogen Supply in the Helophyte Glyceria spiculosa (Gramineae). Aquat. Bot. 2021, 175, 103449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Xie, Y. Growth and Morphological Responses to Water Level and Nutrient Supply in Three Emergent Macrophyte Species. Hydrobiologia 2009, 624, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.B.; Andrews, H.M.; Fischer, A.; Cencer, M.; Coiro, L.; Kelley, S.; Wigand, C. Growth and Photosynthesis Responses of Two Co-Occurring Marsh Grasses to Inundation and Varied Nutrients. Botany 2015, 93, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobacho, S.P.; Janssen, S.A.R.; Brekelmans, M.A.C.P.; van de Leemput, I.A.; Holmgren, M.; Christianen, M.J.A. High Temperature and Eutrophication Alter Biomass Allocation of Black Mangrove (Avicennia germinans L.) Seedlings. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 193, 106291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloey, T.M.; Hester, M.W. Impact of Nitrogen and Importance of Silicon on Mechanical Stem Strength in Schoenoplectus Acutus and Schoenoplectus Californicus: Applications for Restoration. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 26, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Song, W.; Feng, J.; Jia, D.; Guo, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, H.; Qi, F.; Liang, J.; Lin, G. Increased Nitrogen Input Enhances Kandelia Obovata Seedling Growth in the Presence of Invasive Spartina alterniflora in Subtropical Regions of China. Biol. Lett. 2017, 13, 20160760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschamps, L.; Maire, V.; Chen, L.; Fortier, D.; Gauthier, G.; Morneault, A.; Hardy-Lachance, E.; Dalcher-Gosselin, I.; Tanguay, F.; Gignac, C.; et al. Increased Nutrient Availability Speeds up Permafrost Development, While Goose Grazing Slows It down in a Canadian High Arctic Wetland. J. Ecol. 2023, 111, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.H.; Doyle, T.W.; Draugelis-Dale, R.O. Interactive Effects of Substrate, Hydroperiod, and Nutrients on Seedling Growth of Salix nigra and Taxodium nistichum. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2006, 55, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Javed, Q.; Du, Y.; Azeem, A.; Abbas, A.; Iqbal, B.; He, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Du, D. Invasive Alternanthera philoxeroides Has Performance Advantages over Natives under Flooding with High Amount of Nitrogen. Aquat. Ecol. 2022, 56, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozdzer, T.J.; Megonigal, J.P. Jack-and-Master Trait Responses to Elevated CO2 and N: A Comparison of Native and Introduced Phragmites australis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwillie, C.; McCoy, M.W.; Peralta, A.L. Long-term Nutrient Enrichment, Mowing, and Ditch Drainage Interact in the Dynamics of a Wetland Plant Community. Ecosphere 2020, 11, e03252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.; Humphreys, E.; Moore, T.R. Microclimatic Response to Increasing Shrub Cover and Its Effect on Sphagnum CO2 Exchange in a Bog. Ecoscience 2012, 19, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, H.; Liu, M.; Li, B.; Nie, M. Native Herbivores Indirectly Facilitate the Growth of Invasive Spartina in a Eutrophic Saltmarsh. Ecology 2022, 103, e3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A.H. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Differentially Affect Annual and Perennial Plants in Tidal Freshwater and Oligohaline Wetlands. Estuaries Coasts 2013, 36, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangremond, E.M.; Simpson, L.T.; Osborne, T.Z.; Feller, I.C. Nitrogen Enrichment Accelerates Mangrove Range Expansion in the Temperate-Tropical Ecotone. Ecosystems 2020, 23, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, A.C.; Lambrinos, J.G.; Grosholz, E.D. Nitrogen Inputs Promote the Spread of an Invasive Marsh Grass. Ecol. Appl. 2007, 17, 1886–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanco, L.; Irvine, I.C.; Martiny, J.B.H. Nonlinear Responses in Salt Marsh Functioning to Increased Nitrogen Addition. Ecology 2015, 96, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.-B.; Zhou, M.-Y.; Qin, Y.-L.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Dong, M. Nutrient Effects on Aquatic Litter Decomposition of Free-Floating Plants Are Species Dependent. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 30, e01748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinzke, T.; Li, G.; Tanneberger, F.; Seeber, E.; Aggenbach, C.; Lange, J.; Kozub, L.; Knorr, K.-H.; Kreyling, J.; Kotowski, W. Potentially Peat-Forming Biomass of Fen Sedges Increases with Increasing Nutrient Levels. Funct. Ecol. 2021, 35, 1579–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macek, P.; Rejmankova, E. Response of Emergent Macrophytes to Experimental Nutrient and Salinity Additions. Funct. Ecol. 2007, 21, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; Song, C.-C.; Zhang, X.-H.; Wang, X.-W.; Zhang, Z.-H. Response of Leaf, Sheath and Stem Nutrient Resorption to 7 Years of N Addition in Freshwater Wetland of Northeast China. Plant Soil 2013, 364, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, A.; Johnson, R.; Wigand, C.; Oczkowski, A.; Davey, E.; Markham, E. Responses of Spartina alterniflora to Multiple Stressors: Changing Precipitation Patterns, Accelerated Sea Level Rise, and Nutrient Enrichment. Estuaries Coasts 2016, 39, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Song, C.; Nkrumah, P.N. Responses of Ecosystem Carbon Dioxide Exchange to Nitrogen Addition in a Freshwater Marshland in Sanjiang Plain, Northeast China. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 180, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, S.; Wu, J.; Li, B.; Nie, M. Root Plasticity Benefits a Global Invasive Species in Eutrophic Coastal Wetlands. Funct. Ecol. 2024, 38, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.L.; Zavaleta, E.S. Salt Marsh as a Coastal Filter for the Oceans: Changes in Function with Experimental Increases in Nitrogen Loading and Sea-Level Rise. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, S.K.; Horrigan, E.J.; Jefferies, R.L. Seasonal Partitioning of Resource Use and Constraints on the Growth of Soil Microbes and a Forage Grass in a Grazed Arctic Salt-Marsh. Plant Soil 2009, 322, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejmankova, E.; Macek, P.; Epps, K. Wetland Ecosystem Changes After Three Years of Phosphorus Addition. Wetlands 2008, 28, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, J.; Michalski, S.G. Strong Divergence in Quantitative Traits and Plastic Behavior in Response to Nitrogen Availability among Provenances of a Common Wetland Plant. Aquat. Bot. 2017, 136, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.A.; Jesse, A.; Tabet, B.; Reef, R.; Keuskamp, J.A.; Lovelock, C.E. The Contrasting Effects of Nutrient Enrichment on Growth, Biomass Allocation and Decomposition of Plant Tissue in Coastal Wetlands. Plant Soil 2017, 416, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reef, R.; Slot, M.; Motro, U.; Motro, M.; Motro, Y.; Adame, M.F.; Garcia, M.; Aranda, J.; Lovelock, C.E.; Winter, K. The Effects of CO2 and Nutrient Fertilisation on the Growth and Temperature Response of the Mangrove Avicennia germinans. Photosynth. Res. 2016, 129, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Implications of Nutrient Loading on Deltaic Wetlands-All Databases. Available online: https://webofscience.clarivate.cn/wos/alldb/full-record/PQDT:68817634 (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Frevola, D.M.; Hovick, S.M. The Independent Effects of Nutrient Enrichment and Pulsed Nutrient Delivery on a Common Wetland Invader and Its Native Conspecific. Oecologia 2019, 191, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, S.R.; Daleo, P.; DeLaMater, D.S.; Silliman, B.R. Variable Responses to Top-down and Bottom-up Control on Multiple Traits in the Foundational Plant, Spartina alterniflora. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, A.; Wenxuan, M.; Changyan, T.; Javed, Q.; Abbas, A. Competition and Plant Trait Plasticity of Invasive (Wedelia trilobata) and Native Species (Wedelia Chinensis, WC) under Nitrogen Enrichment and Flooding Condition. Water 2021, 13, 3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]