Phytoengineered Remediation of BTEX and MTBE Through Hybrid Constructed Wetlands Planted with Heliconia latispatha and Phragmites australis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Plant Collection

2.3. Description of the Constructed Wetland System and Wastewater Characterization

2.4. Dimensions of the Constructed Wetland System

2.5. Environmental Variables, Water Quality, BTEX, and MTBE

2.6. Contaminant Removal Calculation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Vegetative Development

3.2. In Situ Monitored Variables (pH, DO, WT, EC)

3.3. Removal of Conventional Pollutants

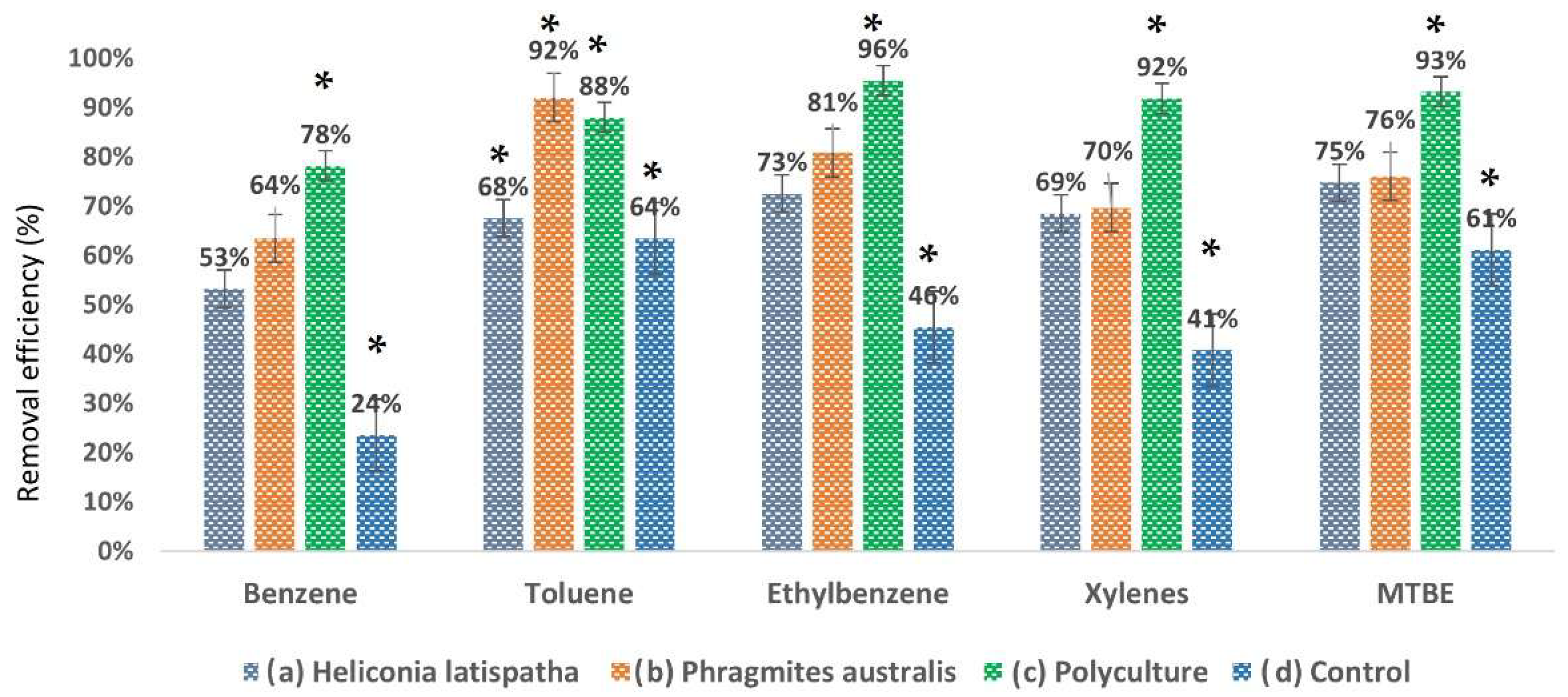

3.4. BTEX and MTBE Contaminants

4. Conclusions

Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mustafa, A.; Azim, M.K.; Raza, Z.; Kori, J.A. BTEX removal in a modified free water surface wetland. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 333, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhiladas, E.K.; Chakraborty, S. Bioremediation of petroleum refinery wastewater using constructed wetlands: A focus on microbial diversity and pollutant degradation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2025, 204, 106152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.J.; Hannigan, J.H.; Bowen, S.E. Effects of inhaled combined benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes (BTEX): Toward an environmental exposure model. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 81, 103518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanakis, A.I. Constructed wetlands case studies for the treatment of water polluted with fuel and oil hydrocarbons. In Phytoremediation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thullner, M.; Stefanakis, A.I.; Dehestani, S. Constructed wetlands treating water contaminated with organic hydrocarbons. In Constructed Wetlands for Industrial Wastewater Treatment; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayaroth, M.P.; Marchel, M.; Boczkaj, G.; Aravindakumar, C. Advanced oxidation processes for the removal of mono and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, X. Perception value of product-service systems: Neural effects of service experience and customer knowledge. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanakis, A. The role of constructed wetlands as green infrastructure for sustainable urban water management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, H.; Johari, K.; Gnanasundaram, N.; Ganesapillai, M.; Arunagiri, A.; Regupathi, I.; Thanabalan, M. A review on adsorptive removal of oil pollutants (BTEX) from wastewater using carbon nanotubes. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 277, 1005–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanakis, A.I. The fate of MTBE and BTEX in constructed wetlands. Appl. Sci. 2019, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabahi, J.; Bora, T.; Al-Abri, M.; Dutta, J. Efficient visible light photocatalysis of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene (BTEX) in aqueous solutions using supported zinc oxide nanorods. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokif, L.A.; Jasim, H.K.; Abdulhusain, N.A. Petroleum and oily wastewater treatment methods: A mini review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 2671–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Muñiz, J.L.; Sandoval Herazo, L.C.; López-Méndez, M.C.; Sandoval-Herazo, M.; Meléndez-Armenta, R.Á.; González-Moreno, H.R.; Zamora, S. Treatment wetlands in Mexico for control of wastewater contaminants: A review of experiences during the last twenty-two years. Processes 2023, 11, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werkneh, A.A. Decentralized constructed wetlands for domestic wastewater treatment in developing countries: Field-scale case studies, overall performance and removal mechanisms. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 57, 104710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, E.; Gikas, P.; Tchobanoglous, G. BTEX removal in pilot-scale horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetlands. Desalination Water Treat. 2013, 51, 3032–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, F.; Vuong, T.H.; Secondes, M.F.; Tuan, P.D. Removal efficiencies of constructed wetland and efficacy of plant on treating benzene. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2016, 26, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega De Lille, M.I.; Hernández Cardona, M.A.; Tzakum Xicum, Y.A.; Giácoman-Vallejos, G.; Quintal-Franco, C.A. Hybrid constructed wetlands system for domestic wastewater treatment under tropical climate: Effect of recirculation strategies on nitrogen removal. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 166, 106243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association (APHA). Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; Eaton, A.D., Clesceri, L.S., Rice, E.W., Greenberg, A.E., Eds.; APHA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). Método 8260D (SW-846) de la EPA: Compuestos Orgánicos Volátiles mediante Cromatografía de Gases y Espectrometría de Masas (GC/MS); US EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). Se publica NOM-001-SEMARNAT-2021, Que Establece los Límites Permisibles de Contaminantes en las Descargas de Aguas Residuales en Cuerpos Receptores Propiedad de la Nación; Diario Oficial de la Federación: Mexico City, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, H.D.; Vi, H.M.; Dang, H.T.; Narbaitz, R.M. Pollutant removal by Canna generalis in tropical constructed wetlands for domestic wastewater treatment. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2019, 5, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveros, J.A.F.; Martínez-Reséndiz, G.; Zurita, F.; Marín-Muñiz, J.L.; Méndez, M.C.L.; Zamora, S.; Sandoval Herazo, L.C. Partially saturated vertical constructed wetlands and free-flow vertical constructed wetlands for pilot-scale municipal/swine wastewater treatment using Heliconia latispatha. Water 2022, 14, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, L.; Zamora-Castro, S.; Vidal-Álvarez, M.; Marín-Muñiz, J. Role of wetland plants and use of ornamental flowering plants in constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment: A review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Echeverria, E.; Sandoval Herazo, L.C.; Zurita, F.; Betanzo-Torres, E.; Sandoval-Herazo, M. Development of Heliconia latispatha in constructed wetlands, for the treatment of swine/domestic wastewater in tropical climates, with PET as a substitute for the filter medium. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quím. 2022, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Eke, P.E.; Scholz, M.; Huang, S. Processes impacting on benzene removal in vertical-flow constructed wetlands. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanakis, A.I.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Effects of loading, resting period, temperature, porous media, vegetation and aeration on performance of pilot-scale vertical flow constructed wetlands. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 181–182, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabr, M.E.; Salem, M.; Mahanna, H.; Mossad, M. Floating wetlands for sustainable drainage wastewater treatment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, L.A.; Karlanian, M.; Mata, D.A. Importancia del pH y la Conductividad Eléctrica (CE) en los Sustratos para Plantas; INTA Instituto de Floricultura, Ed.; Ediciones INTA: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2018; Available online: https://www.sidalc.net/search/Record/oai:localhost:20.500.12123-16823/Description (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Peralta Vega, A.J.; Vergara Flórez, V.; Marín-Peña, O.; García-Aburto, S.G.; Sandoval Herazo, L.C. Treatment of domestic wastewater in Colombia using constructed wetlands with Canna hybrids and oil palm fruit endocarp. Water 2024, 16, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, J. Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment. Water 2010, 2, 530–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borin, M.; Politeo, M.; De Stefani, G. Performance of a hybrid constructed wetland treating piggery wastewater. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 51, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeger, E.M. Treatment of Groundwater Contaminated with Benzene, MTBE, and Ammonium by Constructed Wetlands. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany, 2012. Available online: https://tobias-lib.ub.uni-tuebingen.de/xmlui/handle/10900/49942 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Romeroa, M.R.R. Remoción de Hidrocarburos en Aguas Residuales Mediante Humedales Construidos de Flujo Subsuperficial Plantados con Canna sp. y Juncus effusus. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Los Andes, Mérida, Venezuela, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, W. Fertilización de Suelos y Nutrición Vegetal, 4th ed.; Agrobiolab: Quito, Ecuador, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Soltanpour, Z.; Mohammadian, Y.; Fakhri, Y. The concentration of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene in ambient air of the gas stations in Iran: A systematic review and probabilistic health risk assessment. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2021, 37, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Ávila, F.; Avilés-Añazco, A.; Cabello-Torres, R.; Guanuchi-Quito, A.; Cadme-Galabay, M.; Gutiérrez-Ortega, H.; Alvarez-Ochoa, R.; Zhindón-Arévalo, C. Application of ornamental plants in constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment: A scientometric analysis. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 7, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocetti, E.; Maine, M.A.; Hadad, H.R.; Mufarrege, M.d.L.M.; Di Luca, G.A.; Sánchez, G.C. Selection of macrophytes and substrates to be used in horizontal subsurface flow wetlands for the treatment of a cheese factory wastewater. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 745, 141100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, J.; Rodriguez, L.; Nuñez, J.; Fernández, F.J.; Villaseñor, J. Design of Horizontal and Vertical Subsurface Flow Systems for Wastewater Treatment: Comparative Analysis. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 111, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix, H.; Arias, C.A. The Use of Vertical Flow Constructed Wetlands for Onsite Treatment of Domestic Wastewater: New Danish Guidelines. Ecol. Eng. 2005, 25, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez, E. Cultivo de las Heliconias. Cultiv. Trop. 2025, 28, 29–35. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=193215858005 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Armstrong, J.; Armstrong, W. Plant Internal Oxygen Transport (Diffusion and Convection) and Measuring and Modelling Oxygen Gradients. In Low-Oxygen Stress in Plants; van Dongen, J., Licausi, F., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2014; Plant Cell Monographs; Volume 21, pp. 267–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadlec, R.H.; Wallace, S.D. Treatment Wetlands, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-56670-526-4. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanakis, A. Constructed Wetlands for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment in Hot and Arid Climates: Opportunities, Challenges and Case Studies in the Middle East. Water 2020, 12, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Species | Quantity | City | Collection Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Heliconia latispatha | 25 | Misantla, Veracruz, Mexico | Tributary of the Pailte River |

| 2 | Phragmites australis | 25 | Misantla, Veracruz, Mexico | Community of Diaz Mirón, Misantla, Veracruz, México |

| Contaminant | Concentration |

|---|---|

| Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) (mg/L−1) | 250–1000 |

| Phosphates (P-PO43−) (mg/L−1) | 250–1000 |

| Phosphorus (P) (mg/L−1) | 25–30 |

| Ammonium (N-NH+) (mg/L−1) | 30–50 |

| Nitrate (N-NO3−) (mg/L−1) | 0–5 |

| Nitrite (N-NO2−) (mg/L−1) | 10–30 |

| Total Nitrogen (TN) (mg/L−1) | 10–30 |

| Benzene (μg/L−1) | 3851 ± 345 |

| Toluene (μg/L−1) | 38,745 ± 3542 |

| Ethylbenzene (μg/L−1) | 7402 ± 787 |

| Xylenes (μg/L−1) | 37,856 ± 6393 |

| 1,2,3 Trimethylbenzene (μg/L−1) | 31,206 ± 1831 |

| MTBE (Methyl tert-butyl ether) (μg/L−1) | 1238 ± 390 |

| Hybrid Wetland System | Wetland Type | Cell(s) | Vegetation | No. of Individuals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | VSSF-CW | V1, V2 | Heliconia latispatha | 4 |

| HSSF-CW | H1, H2 | Heliconia latispatha | 8 | |

| (b) | VSSF-CW | V3, H3 | Phragmites australis | 4 |

| HSSF-CW | V4, H4 | Phragmites australis | 8 | |

| (c) | VSSF-CW | V5 | Heliconia latispatha and Phragmites australis (polyculture) | 2 2 |

| HSSF-CW | H5 | Heliconia latispatha and Phragmites australis (polyculture) | 4 4 | |

| (d) | VSSF-CW | V6 | Control | - |

| HSSF-CW | H6 | Control | - |

| Variable | Unit | Frequency | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | |||

| DO | mg/L−1 | Daily | Portable meter, Hanna Instruments HI98193 |

| Temperature | °C | Daily | Jsman™, model HTC–1 |

| pH | Daily | Portable meter, Hanna Instruments HI98193 | |

| EC | µS/cm | Daily | Portable meter, Jeswo™, model C-600 (China) |

| Physico-chemical | |||

| N-NH3+ | mg/L−1 | Biweekly | APHA (2005) |

| NO2− | mg/L−1 | Biweekly | APHA (2005) |

| NO3− | mg/L−1 | Biweekly | APHA (2005) |

| PO43− | mg/L−1 | Biweekly | APHA (2005) |

| PT | mg/L−1 | Biweekly | APHA (2005) |

| COD | mg/L−1 | Biweekly | APHA (2005) |

| BTEX | mg/L−1 | Monthly | EPA Methods 8260C and 5030C (2016) |

| MTBE | mg/L−1 | Monthly | EPA Methods 8260C and 5030C, (2016) |

| Vegetation | Treatment Type | Height (cm) | Stem Width (cm) | N° of Leaves | New Shoots | Flowering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heliconia latispatha | HSSV-CW | 30.79 ± 2.27 | 1.585 ± 0.12 | 2 ± 0.23 | 1 ± 0.71 | 1.0 ± 0.5 |

| HSSH-CW | 78.10 ± 7.14 | 2.505 ± 0.16 | 5 ± 0.30 | 1 ± 1.41 | 2.25 ± 0.5 | |

| Phragmites australis | HSSV-CW | 72.255 ± 28.14 | 0.785 ± 0.32 | 19 ± 1.65 | 2 ± 0.11 | - |

| HSSH-CW | 80.25 ± 20.90 | 0.56 ± 0.90 | 19 ± 0.76 | 3 ± 0.27 | - |

| (a) Heliconia latispatha | (b) Phragmites australis | (c) Heliconia latispatha + Phragmites australis | (d) Control | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSSF-CW | HSSF-CW | HCW | VSSF-CW | HSSF-CW | HCW | VSSF-CW | HSSF-CW | HCW | VSSF-CW | HSSF-CW | HCW | |

| Stage I * | Stage II ** | Integrated System *** | Stage I * | Stage II ** | Integrated System *** | Stage I * | Stage II ** | Integrated System *** | Stage I * | Stage II ** | Integrated System *** | |

| COD | ||||||||||||

| Affluent (mg L−1) | 298.57 ± 50.07 | 71.36 ± 6.34 | 298.57 ± 50.07 | 298.57 ± 50.07 | 57.14 ± 6.34 | 298.57 ± 50.07 | 298.57 ± 50.07 | 79.43 ± 1.26 | 298.57 ± 50.07 | 298.57 ± 50.07 | 180 ± 29.32 | 298.57 ± 50.07 |

| Effluent (mg L−1) | 71.36 ± 6.34 | 46.64 ± 6.96 | 46.64 ± 6.96 | 57.14 ± 6.34 | 40.57 ± 5.14 | 40.57 ± 5.14 | 79.43 ± 1.26 | 39 ± 3.86 | 39 ± 3.86 | 180 ± 29.32 | 97.71 ± 12.55 | 97.71 ± 12.55 |

| Removal (%) | 71.43 ± 5.9 | 35.46 ± 8.84 | 82.45 ± 3.14 | 76.97 ± 3.9 | 26.89 ± 5.86 | 83.6 ± 3.5 | 67.25 ± 8.17 | 49.92 ± 7.03 | 83.17 ± 4.14 | 37.99 ± 4.27 | 46.81 ± 3.35 | 64.57 ± 4.16 |

| Phosphate | ||||||||||||

| Affluent (mg L−1) | 18.2 ± 3.05 | 7.46 ± 3.44 | 18.2 ± 3.05 | 18.2 ± 3.05 | 5.55 ± 1.81 | 18.2 ± 3.05 | 18.2 ± 3.05 | 8.06 ± 2.02 | 18.2 ± 3.05 | 18.2 ± 3.05 | 10.17 ± 2.59 | 18.2 ± 3.05 |

| Effluent (mg L−1) | 7.46 ± 3.44 | 2.52 ± 0.61 | 2.52 ± 0.61 | 5.55 ± 1.81 | 3.78 ± 0.9 | 3.78 ± 0.9 | 8.06 ± 2.02 | 3.72 ± 0.67 | 3.72 ± 0.67 | 10.17 ± 2.59 | 7.26 ± 1.21 | 7.26 ± 1.21 |

| Removal (%) | 62.38 ± 11.3 | 56.08 ± 10.7 | 78.88 ± 5.56 | 70.71 ± 8.82 | 37.1 ± 7.41 | 70.67 ± 9.47 | 56.71 ± 9.56 | 46.22 ± 9.74 | 71.16 ± 8.77 | 48.29 ± 5.43 | 33.74 ± 4.85 | 56 ± 0.06 |

| Total Phosphorus | ||||||||||||

| Affluent (mg L−1) | 7.36 ± 0.96 | 1.73 ± 0.42 | 7.36 ± 0.96 | 7.36 ± 0.96 | 1.17 ± 0.57 | 7.36 ± 0.96 | 7.36 ± 0.96 | 1.51 ± 0.34 | 7.36 ± 0.96 | 7.36 ± 0.96 | 4.29 ± 0.58 | 7.36 ± 0.96 |

| Effluent (mg L−1) | 1.73 ± 0.42 | 0.82 ± 0.23 | 0.82 ± 0.23 | 1.17 ± 0.57 | 0.79 ± 0.36 | 0.79 ± 0.36 | 1.51 ± 0.34 | 0.88 ± 0.32 | 0.88 ± 0.32 | 4.29 ± 0.58 | 2.79 ± 0.32 | 2.79 ± 0.32 |

| Removal (%) | 72.27 ± 9.04 | 56.03 ± 8.47 | 56 ± 6.18 | 81.42 ± 5.85 | 43.48 ± 14.39 | 87.76 ± 4.92 | 75.29 ± 7.2 | 46.33 ± 9.14 | 88.6 ± 4.16 | 39.86 ± 4.52 | 30.44 ± 6.38 | 60.23 ± 4.23 |

| Ammonium | ||||||||||||

| Affluent (mg L−1) | 32.8 ± 8.08 | 12.63 ± 4.58 | 32.8 ± 8.08 | 32.8 ± 8.08 | 9.74 ± 1.98 | 32.8 ± 8.08 | 32.8 ± 8.08 | 15.59 ± 2.46 | 32.8 ± 8.08 | 32.8 ± 8.08 | 14.71 ± 3.69 | 32.8 ± 8.08 |

| Effluent (mg L−1) | 12.63 ± 4.58 | 8.61 ± 3.66 | 8.61 ± 3.66 | 9.74 ± 1.98 | 5.09 ± 0.98 | 5.09 ± 0.98 | 15.59 ± 2.46 | 8.39 ± 1.68 | 8.39 ± 1.68 | 14.71 ± 3.69 | 9.9 ± 2.03 | 14.71 ± 3.69 |

| Removal (%) | 66.92 ± 7.22 | 42.9 ± 7.22 | 78.56 ± 6.62 | 65.66 ± 7.09 | 44.35 ± 3.72 | 81.88 ± 3.24 | 42.26 ± 10.91 | 45.18 ± 4.35 | 70.28 ± 4.19 | 55.05 ± 4.59 | 28.08 ± 6.21 | 68.69 ± 1.8 |

| Nitrate | ||||||||||||

| Affluent (mg L−1) | 3.36 ± 1 | 1.96 ± 0.56 | 3.36 ± 1 | 3.36 ± 1 | 1.88 ± 0.54 | 3.36 ± 1 | 3.36 ± 1 | 1.14 ± 0.32 | 3.36 ± 1 | 3.36 ± 1 | 1.86 ± 0.53 | 3.36 ± 1 |

| Effluent (mg L−1) | 1.96 ± 0.56 | 0.87 ± 0.29 | 0.87 ± 0.29 | 1.88 ± 0.54 | 1.09 ± 0.36 | 1.09 ± 0.36 | 1.14 ± 0.32 | 0.22 ± 0.1 | 0.22 ± 0.1 | 1.86 ± 0.53 | 1.58 ± 0.46 | 1.58 ± 0.46 |

| Removal (%) | 43.9 ± 10.16 | 58.58 ± 9.66 | 74.77 ± 7.53 | 46.65 ± 8.64 | 46.56 ± 8.8 | 67.95 ± 7.98 | 52.39 ± 11.52 | 71.7 ± 12.66 | 88.33 ± 6.22 | 41.71 ± 10.41 | 17.79 ± 0.03 | 52.36 ± 7.31 |

| Nitrite | ||||||||||||

| Affluent (mg L−1) | 16.64 ± 3.27 | 9.61 ± 2.46 | 16.64 ± 3.27 | 16.64 ± 3.27 | 9.13 ± 2.69 | 16.64 ± 3.27 | 16.64 ± 3.27 | 11.75 ± 2.92 | 16.64 ± 3.27 | 16.64 ± 3.27 | 11.34 ± 4.11 | 16.64 ± 3.27 |

| Effluent (mg L−1) | 9.61 ± 2.46 | 6.59 ± 2.08 | 6.59 ± 2.08 | 9.13 ± 2.69 | 5.82 ± 2.4 | 5.82 ± 2.4 | 11.75 ± 2.92 | 5.64 ± 2.78 | 5.64 ± 2.78 | 11.34 ± 4.11 | 8.43 ± 3.56 | 8.43 ± 3.56 |

| Removal (%) | 43.31 ± 6.74 | 40.87 ± 8.82 | 65.65 ± 8.08 | 48.45 ± 7.74 | 47.58 ± 9.19 | 72.32 ± 8.24 | 45.73 ± 6.66 | 63.04 ± 13.16 | 76 ± 10.29 | 41 ± 12.2 | 38.43 ± 6.46 | 61.15 ± 11.91 |

| Total Nitrogen | ||||||||||||

| Affluent (mg L−1) | 23.57 ± 3.69 | 11.21 ± 1.39 | 23.570 | 23.57 ± 3.69 | 9.07 ± 0.64 | 23.57 ± 3.69 | 23.57 ± 3.69 | 9.71 ± 1.18 | 23.57 ± 3.69 | 23.57 ± 3.69 | 14.71 ± 2.91 | 23.57 ± 3.69 |

| Effluent (mg L−1) | 11.21 ± 1.39 | 7.54 ± 0.81 | 7.54 ± 0.81 | 9.07 ± 0.64 | 7.14 ± 0.83 | 7.14 ± 0.83 | 9.71 ± 1.18 | 7.79 ± 0.89 | 7.79 ± 0.89 | 14.71 ± 2.91 | 11 ± 1.2 | 11 ± 1.2 |

| Removal (%) | 48.16 ± 7.14 | 28.8 ± 6.74 | 64.75 ± 4.67 | 55.61 ± 8.01 | 21.73 ± 6.89 | 66.02 ± 5.48 | 54.42 ± 6.47 | 16.94 ± 7.11 | 63.77 ± 4.5 | 33.73 ± 6.15 | 21.24 ± 3.94 | 48.81 ± 6.71 |

| (a) Heliconia latispatha | (b) Phragmites australies | (c) Heliconia latispatha + Phragmites australis | (d) Control | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSSF-CW | HSSF-CW | HCW | VSSF-CW | HSSF-CW | HCW | VSSF-CW | HSSF-CW | HCW | VSSF-CW | HSSF-CW | HCW | |

| Stage I * | Stage II ** | Integrated System *** | Stage I * | Stage II ** | Integrated System *** | Stage I * | Stage II ** | Integrated System *** | Stage I * | Stage II ** | Integrated System *** | |

| Benzene | ||||||||||||

| Affluent (mg L−1) | 4.96 ± 0.27 | 2.64 ± 0.19 | 4.96 ± 0.27 | 4.96 ± 0.27 | 1.99 ± 0.65 | 4.96 ± 0.27 | 4.96 ± 0.27 | 1.37 ± 0.09 | 4.96 ± 0.27 | 4.96 ± 0.27 | 3.82 ± 0.05 | 4.96 ± 0.27 |

| Effluent (mg L−1) | 2.64 ± 0.19 | 2.31 ±0.12 | 2.31 ± 0.12 | 1.99 ± 0.65 | 1.79 ± 0.38 | 1.79 ± 0.38 | 1.37 ± 0.09 | 1.07 ± 0.11 | 1.07 ± 0.11 | 3.82 ± 0.05 | 3.75 ± 0.04 | 3.75 ± 0.04 |

| Removal (%) | 46.21 ± 4.79 | 12.47 ± 5.39 | 53.26 ± 3.55 | 59.42 ± 13.26 | 8.64 ± 4.05 | 63.5 ± 10.98 | 71.86 ± 3.67 | 21.09 ± 9.58 | 78.21 ± 2.04 | 22.19 ± 4.77 | 1.83 ± 0.48 | 23.61 ± 4.86 |

| Toluene | ||||||||||||

| Affluent (mg L−1) | 46.24 ± 3.91 | 23.28 ± 0.98 | 46.24 ± 3.91 | 46.24 ± 3.91 | 21.32 ± 0.34 | 46.24 ± 3.91 | 46.24 ± 3.91 | 11.14 ± 0.15 | 46.24 ± 3.91 | 46.24 ± 3.91 | 26.46 ± 1.97 | 46.24 ± 3.91 |

| Effluent (mg L−1) | 23.28 ± 0.98 | 15.01 ± 1.03 | 15.01 ± 1.03 | 21.32 ± 0.34 | 3.67 ± 0.59 | 3.67 ± 0.59 | 11.14 ± 0.15 | 5.55 ± 0.2 | 5.55 ± 0.2 | 26.46 ± 1.97 | 16.87 ± 1.06 | 16.87 ± 1.06 |

| Removal (%) | 49.56 ± 2.4 | 34.91 ± 7.68 | 67.6 ± 2.85 | 53.78 ± 1.64 | 82.69 ± 4.1 | 92.06 ± 1.81 | 75.84 ± 0.95 | 50.13 ± 2.5 | 88.00 ± 0.31 | 42.49 ± 4.99 | 35.51 ± 3.58 | 63.52 ± 1.83 |

| Ethylbenzene | ||||||||||||

| Affluent (mg L−1) | 9.38 ± 0.29 | 3.19 ± 1.09 | 9.38 ± 0.29 | 9.38 ± 0.29 | 3.27 ± 1.05 | 9.38 ± 0.29 | 9.38 ± 0.29 | 1.57 ± 0.02 | 9.38 ± 0.29 | 9.38 ± 0.29 | 5.49 ± 0.16 | 9.38 ± 0.29 |

| Effluent (mg L−1) | 3.19 ± 1.09 | 2.57 ±1.00 | 2.57 ± 1.00 | 3.27 ± 1.05 | 1.79 ± 0.58 | 1.79 ± 0.58 | 1.57 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.04 | 5.49 ± 0.160 | 5.08 ± 0.18 | 5.08 ± 0.160 |

| Removal (%) | 65.95 ± 11.64 | 37.3 ± 22.99 | 72.61 ± 15.11 | 65.01 ± 11.21 | 69.73 ± 10.05 | 80.89 ± 0.42 | 83.25 ± 0.68 | 73.15 ± 2.63 | 95.53 ± 0.38 | 41.17 ± 3.42 | 7.13 ± 4.88 | 45.52 ± 3.56 |

| Xylenes | ||||||||||||

| Affluent(mg L−1) | 40.06 ± 1.24 | 16.19 ± 5.23 | 40.06 ± 1.24 | 40.06 ± 1.24 | 16.45 ± 5.24 | 40.06 ± 1.24 | 40.06 ± 1.24 | 9.54 ± 0.33 | 40.06 ± 1.24 | 40.06 ± 1.24 | 25.44 ± 0.22 | 40.06 ± 1.24 |

| Effluent (mg L−1) | 16.19 ± 5.23 | 12.42 ± 3.14 | 12.42 ± 3.14 | 16.45 ± 5.24 | 12.01 ± 3.89 | 12.01 ± 3.89 | 9.54 ± 0.33 | 3.24 ± 0.16 | 3.24 ± 0.16 | 25.44 ± 0.22 | 23.54 ± 0.56 | 23.54 ± 0.56 |

| Removal (%) | 59.12 ± 13.3 | 25.52 ± 5.70 | 68.58 ± 11.34 | 60.21 ± 12.09 | 35.97 ± 13.58 | 69.73 ± 13.88 | 76.10 ± 1.14 | 65.89 ± 2.88 | 91.87 ± 0.55 | 35.96 ± 3.60 | 7.44 ± 3.01 | 40.81 ± 2.96 |

| MTBE | ||||||||||||

| Affluent(mg L−1) | 1.83 ± 0.06 | 0.54 ± 0.26 | 1.83 ± 0.06 | 1.83 ± 0.06 | 0.52 ± 0.23 | 1.83 ± 0.06 | 1.83 ± 0.06 | 0.19 ± 00 | 1.83 ± 0.06 | 1.83 ± 0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 1.83 ± 0.06 |

| Effluent (mg L−1) | 0.54 ± 0.26 | 0.46 ± 0.16 | 0.46 ± 0.160 | 0.52 ± 0.23 | 0.44 ± 0.15 | 0.44 ± 0.15 | 0.19 ± 00 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.71 ± 0.02 |

| Removal (%) | 70.22 ± 14.55 | 14.29 ± 4.04 | 74.84 ± 12.2 | 71.66 ± 12.67 | 22.89 ± 7.56 | 76.07 ± 11.86 | 89.42 ± 0.38 | 35.84 ± 3.25 | 93.24 ± 0.24 | 48.76 ± 3.21 | 23.63 ± 4.7 | 61.22 ± 0.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Aburto, S.G.; Nani, G.; Vergara-Flórez, V.; Reyes-González, D.; Betanzo-Torres, E.A.; Peralta-Vega, A.; Sandoval Herazo, L.C. Phytoengineered Remediation of BTEX and MTBE Through Hybrid Constructed Wetlands Planted with Heliconia latispatha and Phragmites australis. Ecologies 2025, 6, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6040084

García-Aburto SG, Nani G, Vergara-Flórez V, Reyes-González D, Betanzo-Torres EA, Peralta-Vega A, Sandoval Herazo LC. Phytoengineered Remediation of BTEX and MTBE Through Hybrid Constructed Wetlands Planted with Heliconia latispatha and Phragmites australis. Ecologies. 2025; 6(4):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6040084

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Aburto, Sandra Guadalupe, Graciela Nani, Vicente Vergara-Flórez, David Reyes-González, Erick Arturo Betanzo-Torres, Alexi Peralta-Vega, and Luis Carlos Sandoval Herazo. 2025. "Phytoengineered Remediation of BTEX and MTBE Through Hybrid Constructed Wetlands Planted with Heliconia latispatha and Phragmites australis" Ecologies 6, no. 4: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6040084

APA StyleGarcía-Aburto, S. G., Nani, G., Vergara-Flórez, V., Reyes-González, D., Betanzo-Torres, E. A., Peralta-Vega, A., & Sandoval Herazo, L. C. (2025). Phytoengineered Remediation of BTEX and MTBE Through Hybrid Constructed Wetlands Planted with Heliconia latispatha and Phragmites australis. Ecologies, 6(4), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6040084