Abstract

The teaching of the phytosociological method comprises several stages and aligns closely with the research-oriented teaching–learning process promoted by active methodologies. In both cases, preliminary inquiry is essential to review existing knowledge on vegetation in all its dimensions: bioclimatic, biogeographical, ecological, floristic composition, distribution, and conservation status. The main objective is to connect active teaching methodologies with phytosociological research. To this end, the natural environment is used to bring students into direct contact with plant communities, and the phytosociological research method is applied, through which students learn sampling techniques. This approach provides a rapid and effective assessment of habitat conservation status (EU Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC, European Council, 21 May 1992). As notable results, we highlight the poor conservation status of the three communities described, which is evident from the decline in characteristic association species. The present study focuses on the wetlands of the Costa Tropical, where communities of Juncus acutus, Typha dominguensis, Phragmites australis, and Arundo donax predominate. In this case, these communities act as open-air laboratories for teaching the phytosociological method. The Juncus acutus communities differ from those of Scirpus holoschoenus and other Juncus acutus stands by the presence of the endemic Linum maritimum. Meanwhile, the reedbeds differ from Thypho-Phragmitetum australis through the presence of Halimione portulacoides. In both cases, the influence of sea spray conditions the presence of subhalophilous species such as Juncus acutus, Linum maritimum, and Halimione portulacoides. This has enabled us to establish two new plant associations: LmJa = Lino maritimi–Juncetum acuti (rush stands) and Hp–Phra = Halimione portulacoidis–Phragmitetum australis (reedbeds). Ecological gradients also make it possible to separate Typha communities belonging to the Ca–Td = Cynancho acuti–Typhetum dominguensis association, and Phragmites into two distinct associations. This distinction arises because Typha communities require soil water during the summer period, whereas in Phragmites stands the upper soil horizon dries out.

1. Introduction

The formal study of vegetation in Spain, in the modern sense of phytosociology and biogeography, began in the 20th century with key figures such as Luis Ceballos and Salvador Rivas Martínez. Ceballos laid the groundwork through his pioneering contributions, while Rivas Martínez developed the Vegetation Series Map of Spain, drawing on Ceballos’ earlier research and publishing the first version in 1981, which was later revised in 1987 [1,2,3]. This work became a cornerstone of classical phytosociology and formed the basis for subsequent studies on vegetation dynamics, vegetation series, and landscape ecology across Europe [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Phytosociological research, which is widely developed across Europe, is fundamentally grounded in field-based inventories. This requires an active working approach that closely aligns with active teaching methodologies. This dual framework constitutes the main objective of the present study, together with the description of plant communities in order to promote their conservation.

The plant association is the fundamental unit of phytosociology and the primary level of its typological hierarchy. It is conceived as an abstract model, formally derived from vegetation inventories carried out under homogeneous environmental conditions at a given place and time, within a plant community that represents a structurally stable stage in the successional process. Inevitably, plant associations have been shaped by major climatic changes throughout history, as documented by Sánchez and d’Errico [13] over the past 425,000 years.

Every plant association must be clearly defined and, above all, possess a distinctive floristic composition, expressed through a unique combination of species that are statistically faithful to its biogeographical delimitation and habitat. It must also display measurable mesological attributes—bioclimatic, edaphic, catenal, and successional—and be assigned a precise geographical and biogeographical framework. Knowledge of these associations is obtained through the comparative analysis of association relevés, which constitute the only objective evidence of the taxonomic system, with the inventory as their core expression. Associations with similar floristic composition, developmental stage, habitat, and biogeography may be grouped into higher-rank typological units referred to as alliances, orders, and classes. Furthermore, any given plant association may include one or more subassociations whose distributional area is necessarily smaller than that of the association itself (Figures S1 and S2; Supplementary Materials).

In parallel, in Spain, Professors Rivas Goday and Rivas-Martínez advanced the field, and their school gained international recognition through studies on series, geoseries, and geopermaseries. These broadened existing concepts and established an integrated methodology for the study of vegetation units and their dynamics [14,15,16,17]. Until the early 20th century, knowledge of vegetation was framed within the broad concept of the Earth’s major biomes, as outlined by Brockmann-Jerosch and Rübel [18].

The phytosociological approach to the global study of vegetation fits closely with current trends in education, as proposed by authors such as García [19] and Vargas and Acuña [20]. Their pedagogical theories emphasise the acquisition of knowledge through individual experience in direct interaction with the environment. In this context, researchers are fully immersed in the natural setting when conducting phytosociological surveys, rendering the natural environment a genuine research laboratory [21,22]. Recent studies in teaching methodologies advocate practical, experience-based learning (active methodologies) [23], which relates directly to new forms of field-based inquiry beyond the classroom [24,25]. Field-based investigation of the natural environment is entirely compatible with the phytosociological research method [9], which should begin with a physical characterisation of the territory and a review of previous studies—thus requiring preliminary inquiry [26,27].

Fieldwork should ideally be undertaken using project-based learning (PBL) [28,29], which emphasises observation and experimentation. Moreover, it should adopt an interdisciplinary perspective [30,31], integrating knowledge from soil science, climatology, bioclimatology, biogeography, anthropozoogenic studies, and vegetation dynamics, all of which are essential for deducing territorial climax communities [32,33]. A central focus of many researchers in this context is the floristic diversity of plant communities [34].

Characterisation of the study area must include the selection of sampling plots that are homogeneous from both ecological and floristic perspectives, along with careful definition of plot size. The sampling design should incorporate, among other aspects, the determination of minimum area, soil analyses, and the bioclimatic and biogeographical characterisation of the study site, as these are critical for subsequent decision-making.

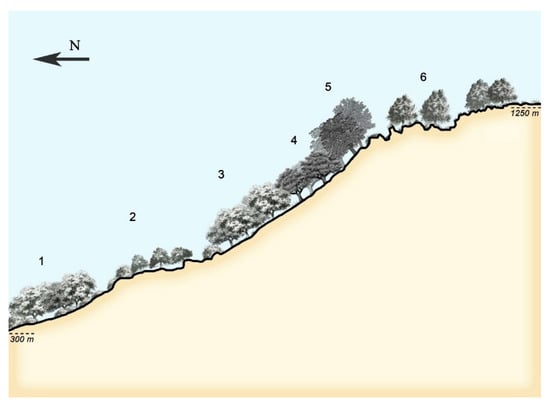

At present, the syntaxa identifiable in the field by vegetation science experts for the Iberian Peninsula are compiled in several works by Professor Rivas-Martínez, published in Itinera Geobotanica [16,17,35]. The holistic (integrated) study of vegetation, an innovative approach largely attributable to the work of Rivas-Martínez [15,36] and Rivas-Martínez et al. [17], incorporates the concepts of vegetation series (synassociations), geoseries, and geopermaseries. These studies are highly significant for establishing vegetation dynamics, with the basic unit of the geoseries being the vegetation series. The vegetation series is composed of a set of plant associations representing different dynamic stages. Analogously, the geoseries consists of a chain of vegetation series that share plant species in their contact zones, thereby defining an ecotone (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Vegetation geoseries composed of four climatophilous series (1, 3, 4, 5; siliceous soils of the cambisol type) and two edapho-xerophilous series (2, 6; rocky siliceous soils of the lithosol type).

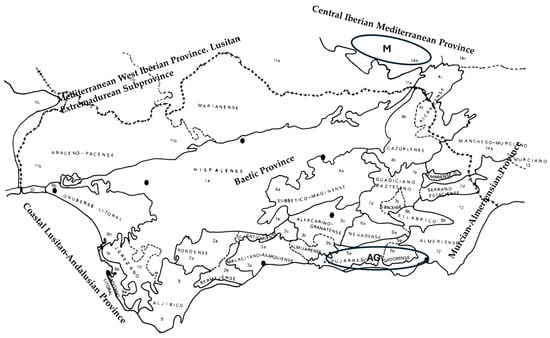

In the preliminary study, the concept of plant association was examined [37], and it was observed that different authors supported the biogeographical distribution of associations. However, no consistent assignment of associations to a specific biogeographical rank was identified. As a result, some associations are described exclusively for a district, others for a sector, and still others span several biogeographical sectors, with no clear correspondence between the characteristic species of a given syntaxon and its distribution. For example, the association Violetum cazorlensis is restricted to the Cazorlense and Maginense districts, whereas Paeonio coriaceae–Quercetum rotundifoliae occurs across numerous biogeographical sectors within the Betic Province (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Association Violetum cazorlensis distributed in the Cazorlense and Maginense districts.

As a consequence of the studies carried out by Professor Rivas-Martínez and collaborators, during the 1990s and early 21st century numerous doctoral theses were developed in Spain focusing on the syntaxonomy of large territories in Spain and Portugal. These works either compiled syntaxa previously described by earlier authors or proposed new syntaxa for science [38,39,40,41,42,43]. Once the description of syntaxa had been consolidated, attention shifted towards their applicability. As a result of this research, the EU issued the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC, and Spain published the Atlas and Manual of Habitats [44,45], followed by further studies on the practical application of syntaxa, such as those by Cano-Ortiz, Cano-Ortiz et al., Leiva, and Spampinato et al. [46,47,48,49,50,51].

The fundamental aim of this research is to highlight the correspondence between phytosociological methodology and active teaching methodologies, as field-based research requires a holistic and integrated learning process. To this end, we present a case study of plant communities on the Tropical Coast (Spain).

2. Materials and Methods

The teaching of the phytosociological method comprises several steps: defining the study area, conducting a literature review through inquiry [26,27], selecting sampling plots and determining their size, and recording plot characteristics, including flora and abundance indices [9].

1. Definition of the study area  . 2. Literature inquiry

. 2. Literature inquiry  . 3. Selection of sampling plots

. 3. Selection of sampling plots  . 4. Determination of plot size

. 4. Determination of plot size  . 5. Recording ecological data in the plots

. 5. Recording ecological data in the plots  . 6. Recording the flora with abundance indices.

. 6. Recording the flora with abundance indices.

. 2. Literature inquiry

. 2. Literature inquiry  . 3. Selection of sampling plots

. 3. Selection of sampling plots  . 4. Determination of plot size

. 4. Determination of plot size  . 5. Recording ecological data in the plots

. 5. Recording ecological data in the plots  . 6. Recording the flora with abundance indices.

. 6. Recording the flora with abundance indices.During the literature inquiry, students apply the rules established by the International Code of Phytosociological Nomenclature, published by Theurillat et al. [52]. Through this process, they learn how to diagnose new syntaxa for science. They also become familiar with the concepts of new association, nomina mutata, nomina inversa, and name conservation, with special emphasis placed on Definition XIII of the aforementioned Code.

Sampling plots are selected according to the physiognomic homogeneity of the community, which requires ecological homogeneity within each plot. To determine plot size, the minimum area is first established. Comparative phytosociological analyses are then carried out with neighbouring plant communities, and bioclimatic analysis is conducted based on bibliographic sources obtained through inquiry. Phytosociological analysis was performed using cluster analysis in the software PAST 4.03. Floristic diversity was calculated using the Shannon_H diversity index, and conservation status was assessed by analysing the relationship between total diversity and the diversity of characteristic species. Characteristic species are those that remain constant within a community, are faithful to it, and have a defined distribution area. However, because association species are stenophilous, their frequency may decrease, or they may even disappear, due to environmental degradation, being replaced by less stenophilous species such as alliance species or those belonging to neighbouring associations. This leads to an increase in companion species. For this assessment, we followed previous studies on conservation status [53], which state that the conservation status of an association is positive when Shannon_Hca > Shannon_Hco. To establish the conservation status of the associations, we followed Cano-Ortiz and collaborators, who define Shannon_Hca as the Shannon diversity of characteristic species and Shannon_Hco as the Shannon diversity of companion species.

Before applying these analyses, we explained to early-career researchers the concepts of characteristic species, companion species, plant association, and syntaxonomy, thus providing an essential component of scientific literacy [54].

For the application of this method, the study was conducted in a specific territory of the Tropical Coast, located in southern Spain (Tables S1 and S2; Supplementary Materials). This area falls within the following Biogeographical Provinces: Betic, Lusitano–Andalusian Coastal, Western Iberian Mediterranean, and Central Iberian Mediterranean [16] (Figure 3). The territory was selected due to the fragility of its wetlands and the significant pressure exerted by tourism, which necessitates careful spatial planning to reconcile development and conservation. For this reason, the phytosociological description and study of plant communities was essential. To achieve this, both bibliographic inquiry (published literature) and field surveys were undertaken to carry out comparative statistical and phytosociological analyses, in accordance with the standards established in the recently published International Code of Phytosociological Nomenclature by Theurillat et al. [52].

Figure 3.

Territory of the Biogeographical Provinces: Lusitano–Andalusian Coastal, Western Iberian Mediterranean, Central Iberian Mediterranean (M = Manchego Sector), and Betic (AG = Alpujarreño–Gadorense Sector; Granada Province, Andalusia). AG and M indicate sampling areas.

3. Results

This study was conducted in the wetlands of the Tropical Coast, where communities dominated by Juncus acutus, Typha dominguensis, Phragmites australis, and Arundo donax occur. These wetlands are subjected to intense tourist pressure, which is driving their degradation. Due to their proximity to urban areas, they also provide suitable open-air laboratories for teaching the phytosociological method and for describing plant communities.

Juncus acutus communities can be distinguished from stands of Scirpus holoschoenus, as well as from other Juncus acutus communities, by the presence of the endemic Linum maritimum. Similarly, reedmace–reedbeds differ from Typho–Phragmitetum communis through the occurrence of Halimione portulacoides.

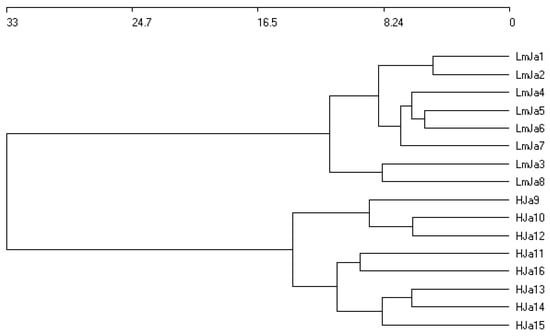

Statistical analysis of Juncus acutus communities in coastal areas of southern Spain revealed two groups of plant communities: LmJa and HJa (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Both are subhalophilous due to the presence of species such as Juncus maritimus, Armeria gaditana, and Artemisia crithmifolia in the HJa association. In contrast, the LmJa association is characterised by differential subhalophilous species, including Linum maritimum, Halimione portulacoides, and Salsola kali. Although both communities share similar ecological conditions, they present distinct catenal relationships and belong to different biogeographical units.

Figure 4.

Cluster analysis of coastal rushlands dominated by Juncus acutus. LmJa = Lino maritimi–Juncetum acuti ass. nova; HJa = Holoschoeno–Juncetum acuti Rivas Martínez 1980.

Figure 5.

Detrended correspondence analysis (DCA). LmJa = Lino maritimi–Juncetum acuti ass. nova (The similar floristic information contained in the inventories is the reason why they appear very close together in the figure); HJa = Holoschoeno–Juncetum acuti Rivas Martínez 1980.

The Juncus acutus community on the Tropical Coast exhibits a cover range of 80–95%, with the dominant species reaching an average height of 1–1.80 m (Figure 6). These rushlands form waterlogged patches that alternate with Phragmites australis communities towards drier zones. The endemic Linum maritimum is frequent, and the vegetation shows a dense structure with an average height between 1 and 1.8 m. The catenal contact of these rushlands occurs with Phragmites australis reedbeds.

Figure 6.

Structure of the rushland Lino maritimi–Juncetum acuti.

Based on their differences from previously described communities, we propose for the thermomediterranean zone with slight halophilous influence in the Alpujarreño–Gadorense Sector the new association Lino maritimi–Juncetum acuti ass. nova (Table 1, relevés LmJa1–LmJa8; holotypus: relevé LmJa2).

Table 1.

Lino maritimi–Juncetum acuti ass. nova.

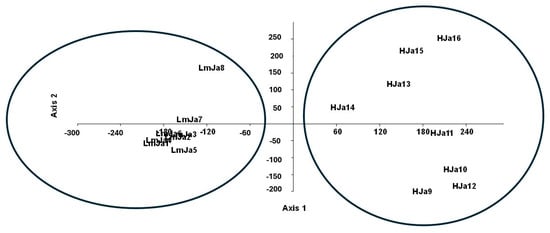

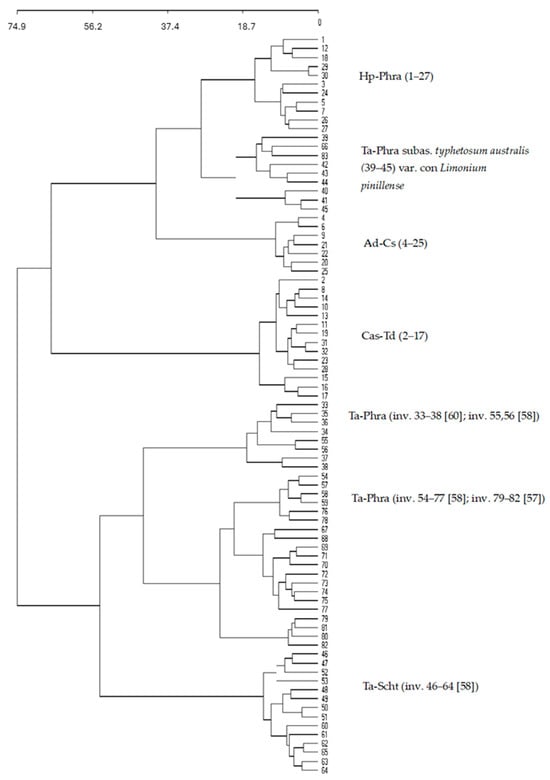

Cluster analysis of communities from the south-central Iberian Peninsula revealed the following groups: Hp–Phra = Halimione portulacoidis–Phragmitetum australis ass. nova; Ta–Phra = Typho angustifoliae–Phragmitetum australis subass. typhetosum dominguensis (ecological variant with Limonium pinillense); Ad–Cs = Arundini donacis–Convolvuletum sepium; Cas–Td = Calystegio sepii–Typhetum dominguensis ass. nova

This analysis shows that some relevés of communities dominated by Typha, Phragmites and Arundo had previously been erroneously assigned to syntaxa lacking statistical support (Figure 7). All of these communities form part of the wetlands of the Tropical Coast.

Figure 7.

Cluster analysis of reedmace (Typha), reed (Phragmites), and giant reed (Arundo) communities from central and southern Iberia. Hp–Phra = Halimione portulacoidis–Phragmitetum australis; Ta–Phra = Typho angustifoliae–Phragmitetum australis subass. typhetosum dominguensis (ecological variant with Limonium pinillense); Ad–Cs = Arundini donacis–Convolvuletum sepium; Cas–Td = Calystegio sepii–Typhetum dominguensis.

The statistical study established several plant groups, among which two new associations are proposed (Hp–Phra; Cas–Td). The association Hp–Phra exhibits 80–100% cover, with dominant species reaching heights of 2.0–3.5 m. Its differences from other Phragmites communities justify the proposal of the new association Halimione portulacoidis–Phragmitetum australis ass. nova (Table 2, relevés 1–11; holotypus: relevé no. 6).

Table 2.

Halimione portulacoidis–Phragmitetum australis ass. nova.

The association Typho angustifoliae–Phragmitetum australis subass. typhetosum dominguensis, widespread throughout Spain—particularly in the salt flats of central Iberia—becomes enriched in halophilous species. This supports the proposal of an ecological variant characterised by the endemic Limonium pinillense, together with Juncus subulatus, Juncus maritimus, Suaeda splendens, and Salicornia patula (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association Typho angustifoliae–Phragmitetum australis subass. typhetosum dominguensis ecological variant with Limonium pinillense.

Communities dominated by Typha dominguensis occupy areas where soil moisture persists during the summer months. These dense stands show almost 100% cover and an average height of 2.5 m, forming near-monospecific assemblages in which Typha dominguensis is dominant with an abundance index of 5 (Figure 8). They are in contact with Phragmites australis reedbeds, which dominate environments where the upper soil layers dry out. Based on their ecological and floristic differences, we propose separating Typha-dominated communities from those of Phragmites, and consequently designate the new association Calystegio sepii–Typhetum dominguensis ass. nova (Table 4, relevés 1–14; holotypus: relevé no. 9).

Figure 8.

Structure of Typha dominguensis communities.

Table 4.

Association Calystegio sepii–Typhetum dominguensis ass. nova.

Cluster analysis of communities from the south-central Iberian Peninsula identified four main groups: Hp–Phra (Halimione portulacoidis–Phragmitetum australis ass. nova), Ta–Phra (Typho angustifoliae–Phragmitetum australis subass. typhetosum dominguensis, ecological variant with Limonium pinillense), Ad–Cs (Arundini donacis–Convolvuletum sepium), and Cas–Td (Calystegio sepii–Typhetum dominguensis ass. nova). The analysis revealed that several relevés of communities dominated by Typha, Phragmites, and Arundo had previously been misassigned to syntaxa not supported by statistical evidence (Figure 9). All these groups form part of the wetland vegetation of the Tropical Coast.

Figure 9.

Structure of Phragmites australis communities.

The statistical study delineated several plant assemblages and supported the proposal of two new associations (Hp–Phra and Cas–Td). The association Hp–Phra displays cover values between 80 and 100%, with dominant species reaching heights of 2.0–3.5 m. Its floristic and ecological distinctiveness in relation to other Phragmites-dominated stands justifies its recognition as the new association Halimione portulacoidis–Phragmitetum australis ass. nova (Table 2, relevés 1–11; holotypus: relevé no. 6).

The diversity analysis of the four syntaxa, based on the Shannon_H index, shows clear differences between total diversity and the diversity of characteristic and companion species. In all cases, total diversity exceeds both characteristic-species diversity and companion-species diversity. Considering that the stability of a plant community depends on the relationship between the diversity of characteristic species and that of companion species, as established by Cano-Ortiz et al. [53], a community is regarded as stable when Shannon_Hc > Shannon_Hco.

In this study, all relevés of the association Cas–Td show Shannon_Hc < Shannon_Hco, indicating instability. A similar pattern is observed in Hp–Phra, where nine plots even present Shannon_Hc = 0. The same situation occurs in Ta–Phra and LmJa (Table 5), underscoring the fragility of these wetland communities under current environmental pressures.

Table 5.

Diversity analysis of the syntaxa studied. Cas–Td = Calystegio sepii–Typhetum dominguenis; LmJa = Lino maritimi–Juncetum acuti; Hp–Phra = Halimione portulacoidis–Phragmitetum australis; Ta–Phra = Typho angustifoliae–Phragmitetum australis subass. typhetosum dominguensis ecological variant with Limonium pinillense.

4. Discussion

In the case study conducted in the Costa Tropical of Granada (Spain), within the thermomediterranean belt of the Alpujarreño–Gadorense biogeographic sector of the Betic Province, the integration of active teaching methodologies with the phytosociological research approach is highlighted. To this end, a preliminary inquiry was carried out on the wetland associations most closely related floristically, situating them within their corresponding biogeographic units.

Following this preliminary phase, fieldwork was conducted, and the phytosociological analysis was undertaken, beginning with the inventory stage. The analytical phase requires an in-depth floristic study, which constitutes the foundation of the system. This involves understanding the autoecology of each species, including physico-chemical and bioclimatic aspects, with particular attention to their distribution areas (biogeography). These elements are fundamental in selecting characteristic species for a given syntaxon.

We propose the Juncus acutus community as a new association, Lino maritimi–Juncetum acuti, for the Alpujarreño–Gadorense sector. This association differs substantially from Holoschoeno–Juncetum acuti described by Rivas-Martínez et al. [55] for thermomediterranean wetlands in the Gaditano–Onubense Littoral sector.

The newly proposed Halimione portulacoidis–Phragmitetum australis represents Phragmites australis communities in thermomediterranean wetlands of the Alpujarreño–Gadorense sector. It is distinguished from the Typho angustifoliae–Phragmitetum australis [56] association by the absence of Typha angustifolia, a species which, according to Molina [57], requires less eutrophic soils than Typha dominguensis. The latter species is widespread across central Iberia. However, Molina [57] describes the subassociation typhetosum dominguensis for mesomediterranean areas of the Manchego biogeographic sector, where both species can coexist under specific conditions.

Typho angustifoliae–Phragmitetum australis was later redescribed under a new name by Rivas-Martínez et al. [58] in their study of the vegetation of the western Pyrenees and Navarre as a Mediterranean association of eutrophic waters with low ion content, intolerant of prolonged drought. The occasional occurrence of the endemic Limonium pinillense in saline environments of the Manchego sector (Lagunas de Ruidera) within the subassociation typhetosum dominguensis allows us to propose an ecological variant characterised by this endemic taxon. Nonetheless, despite its utility as a differential element, the species does not justify recognition as a new syntaxon due to its limited distribution.

The Typho angustifoliae–Phragmitetum australis association has been recorded by various authors in Spain and Portugal across multiple biogeographic provinces. In our study, we identified Ta–Phra = Typho angustifoliae–Phragmitetum australis (relevés 33–38 of Pinto Gomes and Paiva-Ferreira, and relevés 55–56 of Molina) [57,59], all including Typha angustifolia. High abundances of Schoenoplectus lacustris and Typha angustifolia in the Algarve may justify assigning these communities to Schoenoplecto lacustris–Phragmitetum australis. However, the absence of Phragmites australis may exclude them from the Central European Scirpo lacustris–Phragmitetum Koch 1926 = Schoenoplecto–Phragmitetum, suggesting that these communities could instead be included in Typho angustifoliae–Schoenoplectetum tabernaemontani Br.-Bl. & Bolòs 1958 (Ta–Scht). According to Molina [57], Typha dominguensis is widespread in central Iberia and tends to displace Typha angustifolia in eutrophic sites.

The new associations described are confined to the Alpujarreño–Gadorense biogeographic sector. Their significance lies in their role as wetland communities of high ornithological interest, although they are subject to intense tourist pressure that is degrading these habitats. This could be mitigated through a mosaic development strategy, balancing conservation and land-use, by preserving areas of botanical and ecological importance.

Comparative analysis of the new associations with their closest counterparts revealed differences not only in biogeography but also in floristics and ecology. Lino maritimi–Juncetum acuti differs from Holoschoeno–Juncetum acuti by the presence of the endemic Linum maritimum, absent in the Gaditano–Onubense Littoral sector. Halimione portulacoidis–Phragmitetum australis exhibits ecological and floristic differences as a subhalophilous community, including Halimione portulacoides.

No standard exists regarding the correspondence between syntaxon rank and biogeographic rank, highlighting the need for systematic studies correlating syntaxonomic units with biogeographic units, which requires prior research on species distributions. Tentatively, districts and subsectors correspond to subassociations; sectors to associations; subprovinces to suballiances; provinces to alliances; groups of provinces (subregions) to orders; and biogeographic subregions–regions to classes. This hypothesis is based on the distributional breadth of species, considering their stenotopic or eurytopic nature, combined with the hierarchical system of syntaxonomic ranks: subassociation → association → suballiance → alliance → order → class. Close correlation between syntaxonomic and biogeographic systems is thus expected, warranting further detailed investigations.

Consequently, in the preliminary inquiry phase, researchers must rigorously analyse species distributions, accounting for both stenotopic (characteristic) and eurytopic (companion) species of each syntaxon.

The new association Calystegio sepii–Typhetum dominguensis develops under thermomediterranean conditions in the Alpujarreño–Gadorense sector, in eutrophic waters rich in mineral ions. This community is restricted to areas with permanent flooding, typically surrounded by Phragmites australis stands, which tolerate prolonged summer droughts. Traditionally, association names have been assigned based on Typha and Phragmites presence without considering soil moisture gradients; we argue this overlooks distinct ecological niches.

Following the first phase, diversity was assessed using the Shannon_H index. The conservation status of an association was evaluated based on the relationship between characteristic and companion species: when Shannon_Hca/Shannon_Hco > 1, the association is considered well conserved, as characteristic species dominate [53]. In our study, all Cas–Td inventories exhibited Shannon_Hca/Shannon_Hco < 1, indicating dominance of companion species. Hp–Phra also showed Shannon_Hca/Shannon_Hco < 1, with 9 of 11 inventories recording Shannon_Hca = 0, indicating poor conservation. In Ta–Phra, one of nine inventories had Shannon_Hca = 0, five were <1, and three were >1. Juncus acutus rushlands also showed Shannon_Hca/Shannon_Hco < 1.

Overall, these results indicate that the study area faces high risk of biodiversity loss and low vegetation stability, primarily due to: (i) eutrophication from adjacent tropical crop cultivation, and (ii) intense tourist pressure.

As in all research, strengths and weaknesses exist. The main strength of this study is the integration of teaching methodologies with the phytosociological research method, using natural habitats as open-air laboratories. A key weakness is the imbalance between theoretical curricula and practical application, underscoring the need to translate theoretical content into hands-on learning experiences.

5. Conclusions

Field-based geobotanical research using the phytosociological method has enabled the identification of three new plant associations and has demonstrated the potential to integrate active learning methodologies with phytosociological research practice. The scientific process, understood as a paradigmatic framework, provides a model for empirical teaching, where observation and experimentation within the natural environment serve as authentic research laboratories. Direct field observation, sampling techniques, and their interpretation form the foundation for project-based teaching and learning.

The initial study of plant communities as fundamental elements of the landscape allows their recognition and, in turn, facilitates the expansion of researchers’ understanding of the natural environment through the integration of ecological, floristic, bioclimatic, and biogeographic components.

The incorporation of active teaching methodologies into phytosociological research has enabled the diagnosis of several syntaxa new to science, clearly differentiated from those described by previous authors on the basis of ecology, floristics, bioclimatology, and biogeography. It has also allowed for the reformulation of proposals for previously described syntaxa.

Application of the Shannon_H index to all species recorded in the plots, to the characteristic species of each syntaxon, and to companion species indicates that the wetlands of the Costa Tropical (Spain) are experiencing significant degradation. This decline is primarily driven by two factors: eutrophication and intense tourist pressure.

Future research should aim to strengthen and consolidate practical, field-based teaching over purely theoretical instruction. Increasing student presence in the field as a natural laboratory will enhance societal knowledge of nature and, consequently, its resilience in the face of natural disasters.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ecologies6040086/s1, Figure S1: Ecotone between associations A and B. showing characteristic species of each association and species common to both. Figure S2. Differential elements g and h corresponding to subassociations within association A. Table S1: Field and bibliographic data of the studied sites (communities of Juncus acutus). Data from Professor Rivas-Martínez were used with the aim of conducting a comparative study with the Juncus acutus communities described by this author for the areas of Doñana National Park, and our own inventories. Table S2. Field and bibliographic data of the studied sites (communities of Phragmites australis and Typha dominguensis). Data from Professors Rivas-Martínez, Loidi, and Molina were also employed perform a comparative analysis with the Phragmites australis reedbeds described for other regions of Spain, and our own inventories.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization. A.C.O. and E.C.; methodology. A.C.O.; software. J.C.P.F.; validation A.C.O., R.Q.C. and E.C.; formal analysis. A.C.O.; investigation. A.C.O.; resources. E.C.; data curation. J.C.P.F.; writing—original draft preparation. A.C.O.; writing—review and editing. A.C.O.; visualisation. R.Q.C.; supervision. E.C.; project administration. E.C.; funding acquisition. E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be requested from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ceballos, L.; Martín Bolaños, M. Estudio Sobre la Vegetación Forestal de la Provincia de Cádiz; Ingenieros de Montes del I.F.I.E.: Madrid, Spain, 1930; pp. 1–413. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos, L.; Vicioso, C. Estudio Sobre la Vegetación y la Flora Forestal de la Provincia de Málaga; Ingenieros de Montes del I.F.I.E.: Madrid, Spain, 1933; pp. 1–346. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos, L.; Ortuño, F. Estudio Sobre la Vegetación y la Flora Forestal de las Canarias occidentales; Ingenieros de Montes del I.F.I.E.: Madrid, Spain, 1951; pp. 1–465. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Blanquet, J.; de Bolòs, O. Datos sobre las comunidades terofíticas de las llanuras del Ebro medio. Collect. Bot. 1954, 4, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Blanquet, J.; Pinto da Silva, A.R.; Rozeira, A. Résultats de deux excursions géobota niques à travers le Portugal septentrional et moyen, II (Chênaies à feuilles caduques [Quercion occidentale] et chênaies à feuilles persistantes [Quercion fagineae] au Portugal). Agron. Lusit. 1956, 18, 167–234. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Blanquet, J.; de Bolòs, O. Les groupements végétaux du bassin moyen de l’Ebre et leur dynamisme. Anales Estac. Exp. Aula Dei 1958, 5, 1–266. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Blanquet, J.; Pinto da Silva, A.R.; Rozeira, A. Résultats de deux excursions géobota niques à travers le Portugal septentrional et moyen, III (Landes à Cistes et Ericacées [Cisto-La vanduletea et Calluno-Ulicetea]). Agron. Lusit. 1965, 23, 229–313. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Blanquet, J.; Braun-Blanquet, G.; Rozeira, A.; Pinto da Silva, A.R. Résultats de trois excursions géobotaniques à travers le Portugal septentrional et moyen. IV–Esquisse sur la végétation dunale. Agron. Lusit. 1972, 33, 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Fitosociología; Blume: Madrid, Spain, 1979; pp. 1–820. [Google Scholar]

- Géhu, J.M. Essai pour un systeme de classification phytosociologique des landes atlantiques françaises. Coll. Phytosociol. 1975, 2, 361–377. [Google Scholar]

- Géhu, J.M.; De Foucault, B.; Delelis-Dusollier, A. Essai sur un schéma synsystématique des végétations arbustives préforestières de l’Europe occidentale. Coll. Phytosociol. 1983, 8, 463–480. [Google Scholar]

- Géhu, J.M.; Géhu-Franck, J. Schéma synsystématique des végétations phanérogamiques halophiles françaises. Doc. Phytosoc. N.S. 1984, 8, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Goñi, M.F.; d’ Errico, F. La historia de la vegetación y el clima del último ciclo climático (OIS5-OIS1, 140.000-10.000 años BP) en la Península Ibérica y su posible impacto sobre los grupos paleolíticos. Museo de Altamira. MONOGRAFÍAS 2005, 20, 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas Goday, S. Vegetación y Florula de la Cuenca Extremeña Del Guadiana; Excma, Ed.; Diputacióón Provincial Badajoz: Badajoz, Spain, 1964; pp 1–799. Available online: https://bibdigital.rjb.csic.es/medias/48/88/d4/46/4888d446-5c1e-4b42-8025-d5474e54cc9a/files/RIV_Veg_Fl_Guad.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Rivas-Martínez, S. Mapa de series, geoseries y geopermaseries de vegetación de España. Itinera Geobotánica 2007, 17, 5–436. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Díaz, T.E.; Fernández-González, F.; Izco, J.; Loidi, J.; Lousa, M.; Penas, A. Vascular PlantCommunities of Spain and Portugal. Itinera Geobot. 2002, 15, 5–922. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S. Mapa de series, geoseries y geopermaseries de vegetación de España. Parte II. Itinera Geobot. 2011, 18, 425–800. [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann-Jerosch, H.; Rübel, E. Die Einteilung der Pflanzengesellschaften Nach Ökologisch-Physiognomischen Gesischtspunkten; Engelmann: Leipzig, Germany, 1912; pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- García, L.S. El constructivismo y su aplicación en el aula. Algunas consideraciones. In Revista Atlante: Cuadernos de Educación y Desarrollo; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Available online: https://www.eumed.net/rev/atlante/2017/06/constructivismo-aula.html (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Vargas, K.; Acuña, J. El constructivismo en las concepciones pedagógicas y epistemológicas de los profesores. Rev. Innova Educ. 2020, 2, 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Ortiz, A.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Rodrigues Meireles, C.I.; Cano, E. Urban Natural Spaces as Laboratories for Learning and Social Awareness. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Ortiz, A.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Musarella, C.M.; Cano, E. Botany Teaching–Learning Proposal Using the Phytosociological Method for University Students’ Study of the Diversity and Conservation of Forest Ecosystems for University Students. Diversity 2024, 16, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandazo-Espinosa, D.M.; Herera Sarango, C.R.; Calderón-Espinoza, J.V. Metodologías activas para el aprendizaje de la asignatura de Ciencias Naturales. Pol. Con. 2022, 7, 1341–1355. [Google Scholar]

- Caraballo Vidal, I.; Pezelj, L.; Ramos-Álvarez, J.J.; Guillen-Gamez, F.D. Level of Satisfaction with the Application of the Collaborative Model of the Flipped Classroom in the Sport of Sailing. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köpeczi-Bócz, T. The Impact of a Combination of Flipped Classroom and Project-Based Learning on the Learning Motivation of University Students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazán, L.G.S. La metodología indagación y el aprendizaje de las Ciencias Natura- les. Polo del Conoc. Rev. Científico Prof. 2021, 6, 63. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8219316 (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Díaz Linares, G.L. Aprendizaje basado en indagación (ABI): Una estrategia para mejorar la enseñanza-aprendizaje de la química. Cienc. Lat. Rev. Científica Multidiscip. 2023, 7, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos Bernal, P. Métodos Alternativos a la Enseñanza Tradicional de Las Ciencias Naturales: El Aprendizaje Basado en Proyectos. 2020, pp. 1–52. Available online: https://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/58861 (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Magaji, A.; Adjani, M.; Coombes, S. A Systematic Review of Preservice Science Teachers’ Experience of Problem-Based Learning and Implementing It in the Classroom. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano López, R.; Chocano, O.; Pérez-Ferra, M. La interdisciplinariedad en la enseñanza de las ciencias experimentales: Estado actual de la cuestión. Roteiro Joaçaba 2022, 47, e30105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cespón, J.L.; Alonso-Rodríguez, J.A.; Rodríguez-Barcia, S.; Gallego, P.P.; Pino-Juste, M.R. Enhancing Employability Skills of Biology Graduates through an Interdisciplinary Project-Based Service Learning Experience with Engineering and Translation Undergraduate Students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, E.; Musarella, C.M.; Cano-Ortiz, A.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Quinto Canas, R.; del Río, S.; Rodrigues Meireles, C.; Raposo, M.; Pinto Gomes, C.J. Research and management of thermophilic cork forests in the central-south of the Iberian Peninsula. Plant Biosyst. 2024, 158, 942–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, E.; Musarella, C.M.; Cano-Ortiz, A.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Quinto Canas, R.; del Río, S.; Rodrigues Meireles, C.; Raposo, M.; Pinto Gomes, C.J. Contribution to the iberian thermomediterranean oak woods (Spain, portugal): The importance of their teaching for the training of experts in environmental management. Plant Biosyst. 2024, 158, 1285–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Ortiz, A. Teaching about biodiversity from phytosociology: Evaluation and conservation. Plant Sociol. 2023, 60, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Fernández-González, F.; Loidi, J.; Lousa, M.; Penas, A. Syntaxonomical checklist of vascular plant communities of Spain and Portugal to association level. Itinera Geobot. 2001, 14, 5–341. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas Martínez, S. Memoria del Mapa de Series de Vegetación de España 1:400.000; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. ICONA: Madrid, Spain, 1987; pp. 1–268.

- Gehù, J.M.; Rivas Martínez, S. Notions Fondamentales de Phytosociologie. Syntaxonomie; Dierschke, H., Ed.; Syntaxonomie. Ber Intern Symposium IV-V; Cramer: Vaduz, Liechtenstein, 1981; pp. 5–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cano Carmona, E. Estudio Fitosociológico de la Sierra de Quintana (Sierra Morena, Jaén). Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 1988; pp. 1–468. [Google Scholar]

- García Fuentes, A. Vegetación y Florula Del Alto Valle del Guadalquivir: Modelos de Regeneración. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, Spain, 1996; pp. 1–518. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Cordero, J.A. Estudio de la Vegetación de Las Sierras de Pandera. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, Spain, 1997; pp. 1–665. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar Mendías, C. Estudio Fitosociológico de la Vegetación Riparia Andaluza (Provincia Bética): Cuenca del Guadiana Menor. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, Spain, 1996; pp. 1–723. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto Gomes, C.J. Estudo Fitossociológico do Barrocal Algarvio (Tavira, Portimão). Doctoral Thesis, Universidade de Évora, Évora, Portugal, 1998; pp. 1–662. [Google Scholar]

- Melendo Luque, M. Cartografía y Ordenación Vegetal de Sierra Morena. Parque Natural de Las Sierras de Cardeña y Montoro (Córdoba). Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, Spain, 1998; pp. 1–595. [Google Scholar]

- Directiva 92/43/CEE del Consejo de 21 de Mayo 1992. Diario Oficial de la Comunidad Europea nº 1.206/7. 1992. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=DOUE-L-1992-81200 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Atlas y Manual de los Hábitats de España. Dirección General de la Conservación de la Naturaleza. Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. 2003. Available online: https://mapahabitatsaragon.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/manual-atlas_habitats_espac3b1a_2003.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Cano-Ortiz, A. Bioindicadores Ecológicos y Manejo de Cubiertas Vegetales Como Herramienta Para la Implantación de Una Agricultura Sostenible. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, Spain, 2007; pp. 1–362. [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Ortiz, A.; Musarella, C.M.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Pinto Gomes, C.J.; del Río, S.; Cano, E. Indicative value of the dominant plant species for a rapid evaluation of the nutritional of soils. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Ortiz, A.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Leiva Gea, F.; Ighbareyeh, J.M.H.; Quinto Canas, R.J.; Rodrigues Meireles, C.I.; Raposo, M.; Pinto Gomes, C.J.; Spampinato, G.; del Río, S.; et al. Climatology, Bioclimatology and Vegetation Cover: Tools to Mitigate Climate Change in Olive Groves. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva Gea, F. Influencia de la Bioclimatología y Técnicas de Cultivo Sobre la Diversidad Florística en Olivares Andaluces. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, Spain, 2021; pp. 1–250. [Google Scholar]

- Spampinato, G.; Massimo, D.E.; Musarella, C.M.; De Paola, P.; Malerba, A.; Musolino, M. Carbon sequestration by cork oak forests and raw material to built up post carbon city. In New Metropolitan Perspectives; Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Bevilacqua, C., Eds.; ISHT 2018. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, 101; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, G.; Malerba, A.; Calabrò, F.; Bernardo, C.; Musarella, C.M. Cork oak forest spatial new valuation toward post carbon city by CO2 sequestration. In Metropolitan Perspectives; Bevilacqua, C., Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Eds.; NMP 2020. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, 178; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy Lozada, D.Y.; Megret Despaigne, R. Caracterización de especies vegetales: Una estrategia de educación ambiental en Paujil-Caquetá. Rev. Científica del Amazon. 2022, 5, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theurillat, J.P.; Willner, W.; Fernández-González, F.; Bültmann, H.; Čarni, A.; Gigante, D.; Mucina, L.; Weber, H. International Code of Phytosociological Nomenclature. 4th edition. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2021, 24, e12491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Ortiz, A.; Musarella, C.M.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Pinto Gomes, C.J.; del Río, S.; Cano, E. Diversity And Conservation Status of Mangrove Communities In Two Large Areas In Central America. Curr. Sci. 2018, 115, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Valdés, E.; Costa, M.; Castroviejo, S. Vegtación de Doñana, Huelva. Lazaroa 1980, 2, 5–190. [Google Scholar]

- Loidi, J.; Biurrum Galarraga, I.; Herrera Gallastegui, M. La vegetación del centro-septentrional de España. Itinera Geobotánica 1997, 9, 161–618. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, J.A. Sobre la vegetación de los humedales de la Península Ibérica (Phragmiti-Magnocaricetea). Lazaroa 1996, 16, 27–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Báscones, J.C.; Díaz González, T.E.; Fernández-González, F.; Loidi, J. La vegetación del Pirineo Occidental y Navarra. Itinera Geobot. 1991, 5, 5–456. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto Gomes, C.J.; Paiva Ferreira, R.J.P. Flora e Vegetação do Barrocal Algarvio; Tavira, P., Ed.; Comissão de Coordenação e Desenvolvimento Regional do Algarve: Faro, Portugal, 2005; pp. 1–353. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).