Druggable Ensembles of Aβ and Tau: Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Biophysics, Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation and Multiscale Modeling for Alzheimer’s

Abstract

1. Introduction

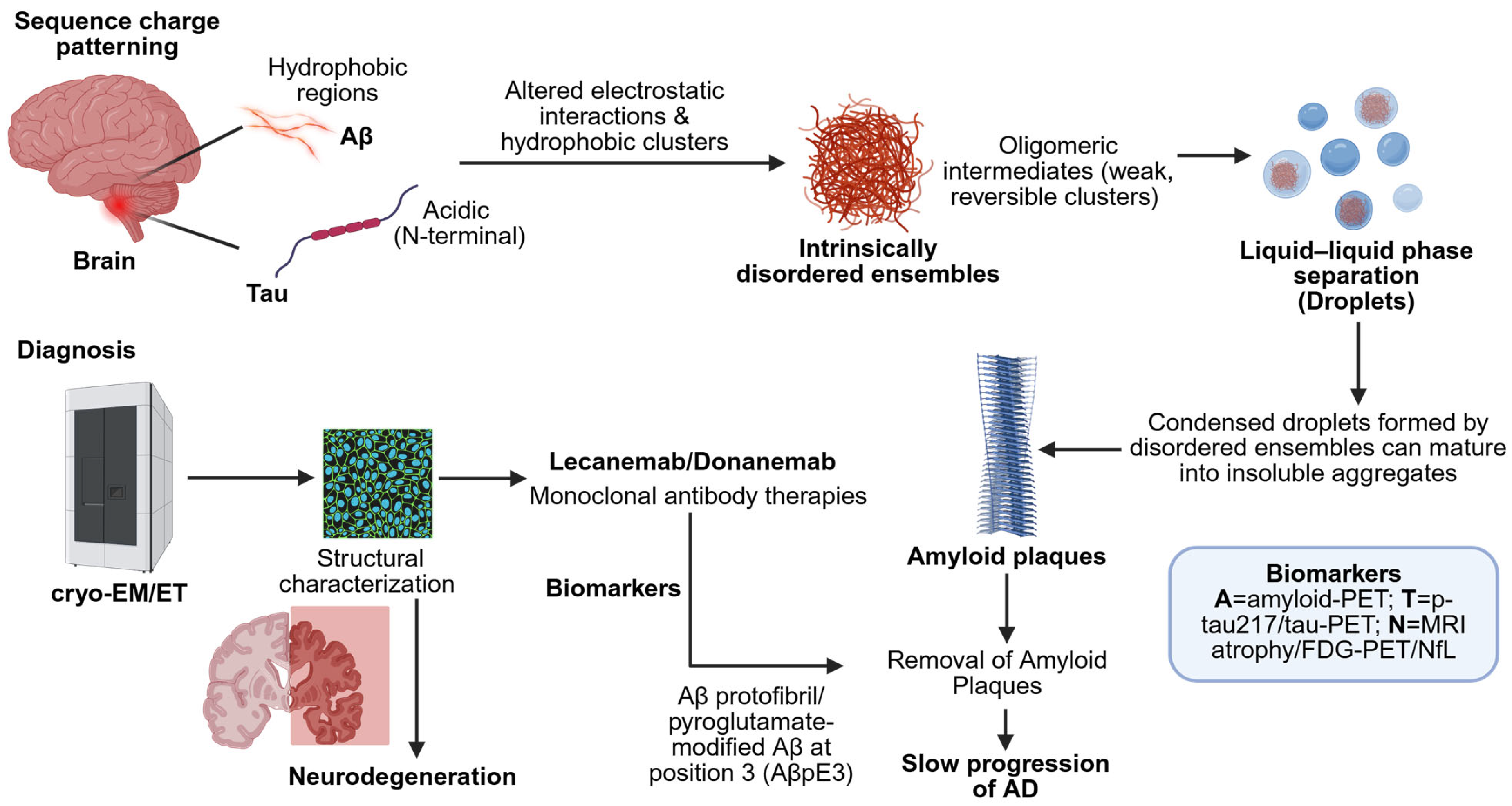

2. Sequence-to-Ensemble Principles That Govern Aβ and Tau

2.1. Sequence Features and the Shape of the Ensemble

2.2. Charge Patterning Connects Chain Compaction and LLPS in Tau

2.3. Disease Mutations as Sequence Edits

2.4. Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) That Shift Ensembles and Condensates

2.5. Implications for Aβ

| Determinant | Typical Experimental Readouts | Expected Qualitative Effect on Ensemble and LLPS | Representative References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Net charge per residue (NCPR) | SAXS Rg, smFRET, single-molecule methods | Larger absolute NCPR expands chains and generally disfavors LLPS at fixed ionic strength. | Mao et al., 2010; Müller-Späth et al., 2010 [21,22]. |

| Charge patterning (κ) | SAXS, smFRET, coarse-grained simulation with sequence variants | Blockier patterns compact chains and can favor condensate formation relative to well-mixed patterns. | Das & Pappu, 2013; Sherry et al., 2017 [6,7]. |

| Aromatic valence and spacing | NMR, SAXS, mutational scans, phase diagrams | More aromatics and certain patterns increase cohesion, compact single chains, and raise LLPS propensity. | Martin et al., 2020 [23]. |

| Stickers and spacers | FRAP, rheology, microscopy, simulations | Sticker enrichment strengthens cohesion; spacer changes the material properties of condensates. | Choi et al., 2020; Dignon et al., 2018 [24,25]. |

| Tau phosphorylation (e.g., AT8) | Phospho-specific immunoassays, LLPS assays, and microscopy | Adds a negative charge, shifts long-range contacts, and can increase LLPS, promoting ageing toward aggregates. | Wegmann et al., 2018; Kanaan et al., 2020 [4,11]. |

| Tau acetylation (e.g., K280, KXGS motifs) | MS mapping, MT-binding assays, aggregation assays | Impairs microtubule binding; it can promote aggregation in cells and mice. KXGS acetylation can also block phosphorylation and reduce aggregation in some systems. | Cohen et al., 2011; Cook et al., 2014 [30,37]. |

| Tau O-GlcNAcylation | O-GlcNAc proteomics, aggregation assays, in vivo models | Stabilizes tau and suppresses aggregation; slows neurodegeneration in mice when increased. | Yuzwa et al., 2012; Yuzwa et al., 2014 [38,39]. |

| Tau truncations | MS-based proteomics, seeding and aggregation assays | Many truncations increase oligomerization and seeding; caspase cleavage promotes aggregation. | Gu et al., 2020; Gamblin et al., 2003; Chu et al., 2023; Gao et al., 2018 [35,40,41,42]. |

| Aβ familial mutations (E22Q/G/K, D23N; A2V/T) | Kinetics, EM, solid-state NMR, cytotoxicity | Alter nucleation and growth rates and the balance of oligomer and fibril states. | Kim et al., 2008; Rezaei-Ghaleh et al., 2023; Park et al., 2021; Benilova et al., 2014 [27,28,29,43] |

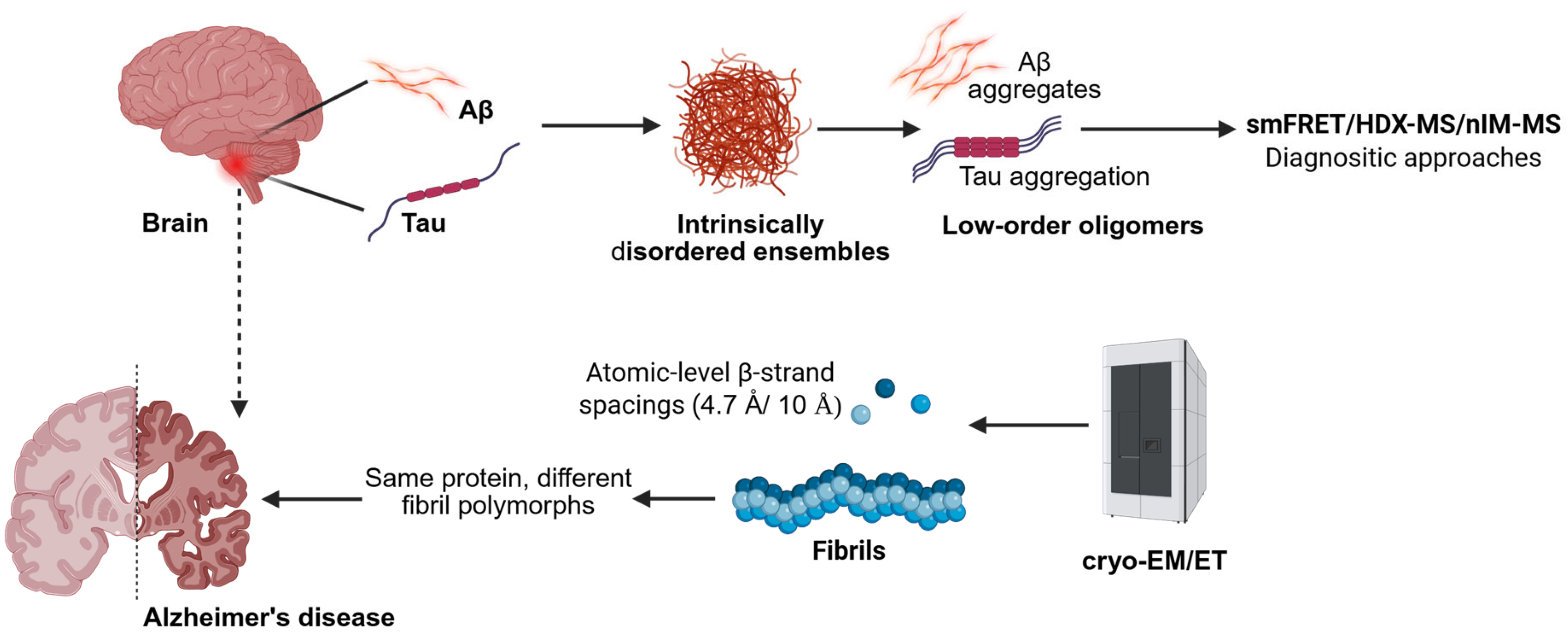

3. Structural Transitions Across Biological Scales: From Monomer to Oligomer, Fibril, and Tissue

3.1. Solution Ensembles and Small Oligomers

3.2. Ex Vivo Fibrils at Near-Atomic Resolution

3.3. In-Tissue Architecture by Cryo-Electron Tomography

3.4. Mass Spectrometry Toolkits for Dynamic Assemblies

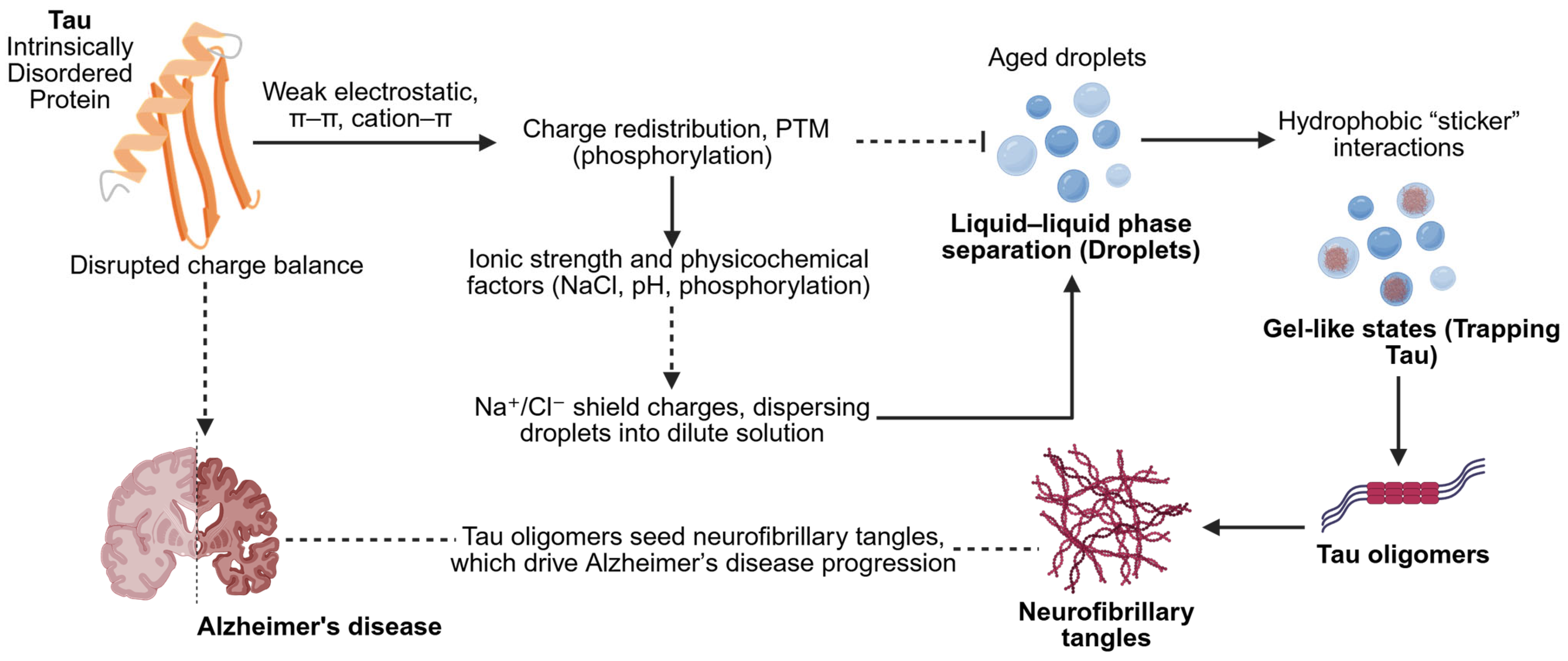

4. LLPS of Tau and Aβ: Evidence, Mechanisms, and Experimental Challenges

4.1. Tau LLPS and Links to Aggregation

4.2. Aβ Condensation as a Context-Dependent Intermediate in Amyloid Assembly

4.3. Conserved Biophysical Mechanisms Underlying LLPS Across Systems

4.4. Experimental Challenges and Reporting Standards

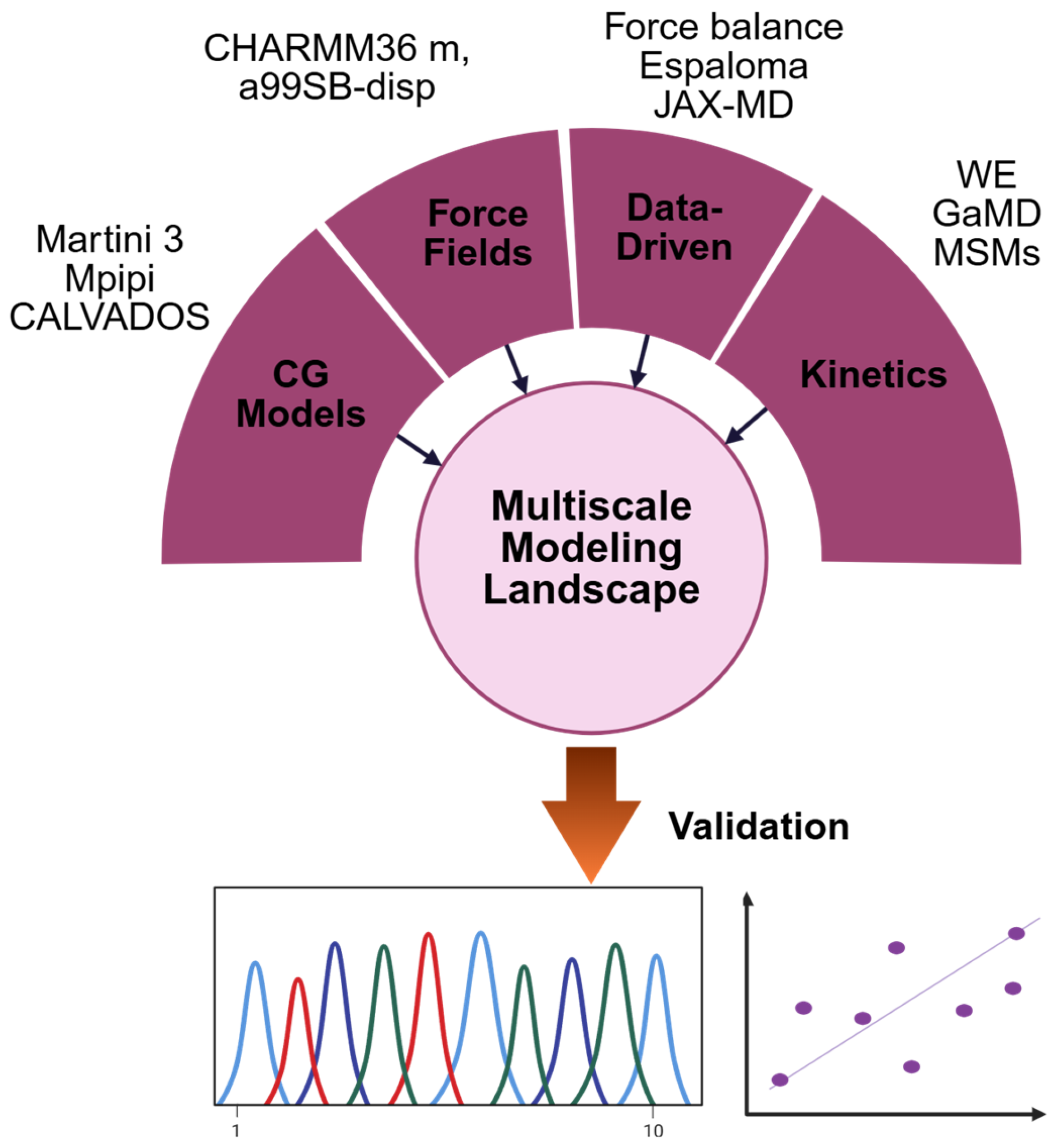

5. Multiscale Computational Modeling of IDPs

5.1. All-Atom Force Fields for IDPs: Advances Toward Physically Realistic Ensemble Simulations

5.2. Emerging Data-Driven and Differentiable Approaches in Force Field Refinement

5.3. Coarse-Grained Modeling of Condensates and Long-Timescale Dynamics

5.4. Ensemble Validation and Optimization Guided by Experimental Data

5.5. Kinetics and Mechanisms at Relevant Timescales

6. Druggability of Dynamic and Condensed States

6.1. Condensate Microenvironments and Small-Molecule Enrichment

6.2. Ensemble-Based Druggability Profiling

6.3. Insights from Clinical Trials of Anti-Aβ Antibodies

6.4. Design Implications for Small Molecules and Biologics

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wright, P.E.; Dyson, H.J. Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, G.T.; Aprile, F.A.; Michaels, T.C.T.; Limbocker, R.; Perni, M.; Ruggeri, F.S.; Mannini, B.; Löhr, T.; Bonomi, M.; Camilloni, C.; et al. Small-molecule sequestration of amyloid-β as a drug discovery strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Hsu, W.; Wu, J. Liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) in cellular physiology and tumor biology. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 3766. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wegmann, S.; Eftekharzadeh, B.; Tepper, K.; Zoltowska, K.M.; Bennett, R.E.; Dujardin, S.; Laskowski, P.R.; MacKenzie, D.; Kamath, T.; Commins, C.; et al. Tau protein liquid–liquid phase separation can initiate tau aggregation. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e98049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, M.A.G.; Fatima, N.; Jenkins, J.; O’sUllivan, T.J.; Schertel, A.; Halfon, Y.; Wilkinson, M.; Morrema, T.H.J.; Geibel, M.; Read, R.J.; et al. CryoET of β-amyloid and tau within postmortem Alzheimer’s disease brain. Nature 2024, 631, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, R.K.; Pappu, R.V. Conformations of intrinsically disordered proteins are influenced by linear sequence distributions of oppositely charged residues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13392–13397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, K.P.; Das, R.K.; Pappu, R.V.; Barrick, D. Control of transcriptional activity by design of charge patterning in the intrinsically disordered RAM region of the Notch receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E9243–E9252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, S.; Gladfelter, A.; Mittag, T. Considerations and Challenges in Studying Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation and Biomolecular Condensates. Cell 2019, 176, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocca, S.; Grandori, R.; Longhi, S.; Uversky, V. Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation by Intrinsically Disordered Protein Regions of Viruses: Roles in Viral Life Cycle and Control of Virus–Host Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meca, E.; Fritsch, A.W.; Iglesias-Artola, J.M.; Reber, S.; Wagner, B. Predicting disordered regions driving phase separation of proteins under variable salt concentration. Front. Phys. 2023, 11, 1213304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaan, N.M.; Hamel, C.; Grabinski, T.; Combs, B. Liquid-liquid phase separation induces pathogenic tau conformations in vitro. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, S.; Surewicz, W.K. Study of Tau Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation In Vitro. Methods Mol. Biol. 2023, 2551, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, S.; Surewicz, K.; Surewicz, W.K. Regulatory mechanisms of tau protein fibrillation under the conditions of liquid–liquid phase separation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 31882–31890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, X.; Feng, S.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Reif, B.; Shi, B.; Niu, Z. Liquid–liquid phase separation of amyloid-β oligomers modulates amyloid fibrils formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 102926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Murzin, A.G.; Falcon, B.; Epstein, A.; Machin, J.; Tempest, P.; Newell, K.L.; Vidal, R.; Garringer, H.J.; Sahara, N.; et al. Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease with PET ligand APN-1607. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 141, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lövestam, S.; Li, D.; Wagstaff, J.L.; Kotecha, A.; Kimanius, D.; McLaughlin, S.H.; Murzin, A.G.; Freund, S.M.V.; Goedert, M.; Scheres, S.H.W. Disease-specific tau filaments assemble via polymorphic intermediates. Nature 2023, 625, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dement. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, N.J.; Brum, W.S.; Di Molfetta, G.; Benedet, A.L.; Arslan, B.; Jonaitis, E.; Langhough, R.E.; Cody, K.; Wilson, R.; Carlsson, C.M.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of a Plasma Phosphorylated Tau 217 Immunoassay for Alzheimer Disease Pathology. JAMA Neurol. 2024, 81, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dyck, C.H.; Swanson, C.J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Reyderman, L.; Cohen, S.; et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, J.R.; Zimmer, J.A.; Evans, C.D.; Lu, M.; Ardayfio, P.; Sparks, J.; Wessels, A.M.; Shcherbinin, S.; Wang, H.; Nery, E.S.M.; et al. Donanemab in Early Symptomatic Alzheimer Disease: The TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 330, 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.-N.W.; Krzeminski, M.; Namini, A.; Martin, E.W.; Mittag, T.; Head-Gordon, T.; Forman-Kay, J.D.; Gradinaru, C.C. Conformational Ensembles of an Intrinsically Disordered Protein Consistent with NMR, SAXS, and Single-Molecule FRET. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 15697–15710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Späth, S.; Soranno, A.; Hirschfeld, V.; Hofmann, H.; Rüegger, S.; Reymond, L.; Nettels, D.; Schuler, B. Charge interactions can dominate the dimensions of intrinsically disordered proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14609–14614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.W.; Holehouse, A.S.; Peran, I.; Farag, M.; Incicco, J.J.; Bremer, A.; Grace, C.R.; Soranno, A.; Pappu, R.V.; Mittag, T. Valence and patterning of aromatic residues determine the phase behavior of prion-like domains. Science 2020, 367, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-M.; Holehouse, A.S.; Pappu, R.V. Physical Principles Underlying the Complex Biology of Intracellular Phase Transitions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2020, 49, 107–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dignon, G.L.; Zheng, W.; Kim, Y.C.; Best, R.B.; Mittal, J. Sequence determinants of protein phase behavior from a coarse-grained model. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1005941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyko, S.; Qi, X.; Chen, T.-H.; Surewicz, K.; Surewicz, W.K. Liquid–liquid phase separation of tau protein: The crucial role of electrostatic interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 11054–11059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Hecht, M.H. Mutations Enhance the Aggregation Propensity of the Alzheimer’s Aβ Peptide. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 377, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Ghaleh, N.; Amininasab, M.; Giller, K.; Becker, S. Familial Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Mutations Differentially Alter Stability of Amyloid-Beta Aggregates. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 1427–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-W.; Wood, C.A.; Li, J.; Taylor, B.C.; Oh, S.; Young, N.L.; Jankowsky, J.L. Gene therapy using Aβ variants for amyloid reduction. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 2294–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, T.J.; Guo, J.L.; Hurtado, D.E.; Kwong, L.K.; Mills, I.P.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.Y. The acetylation of tau inhibits its function and promotes pathological tau aggregation. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.L.; Gray, A.J.; Joyce, J.A.; Yu, D.; O’Moore, J.; Carlson, G.A.; Shearman, M.S.; Dellovade, T.L.; Hering, H. Increased O-GlcNAcylation reduces pathological tau without affecting its normal phosphorylation in a mouse model of tauopathy. Neuropharmacology 2014, 79, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastings, N.B.; Wang, X.; Song, L.; Butts, B.D.; Grotz, D.; Hargreaves, R.; Hess, J.F.; Hong, K.-L.K.; Huang, C.R.-R.; Hyde, L.; et al. Inhibition of O-GlcNAcase leads to elevation of O-GlcNAc tau and reduction of tauopathy and cerebrospinal fluid tau in rTg4510 mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Permanne, B.; Sand, A.; Ousson, S.; Nény, M.; Hantson, J.; Schubert, R.; Wiessner, C.; Quattropani, A.; Beher, D. O-GlcNAcase Inhibitor ASN90 is a Multimodal Drug Candidate for Tau and α-Synuclein Proteinopathies. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 1296–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Shea, T.B. Caspase-Mediated Truncation of Tau Potentiates Aggregation. Int. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012, 2012, 731063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Xu, W.; Jin, N.; Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; Chu, D.; Gong, C.-X.; Iqbal, K.; Liu, F. Truncation of Tau selectively facilitates its pathological activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 13812–13828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Biernat, J.; Pickhardt, M.; Mandelkow, E.; Mandelkow, E.-M. Stepwise proteolysis liberates tau fragments that nucleate the Alzheimer-like aggregation of full-length tau in a neuronal cell model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 10252–10257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.; Carlomagno, Y.; Gendron, T.F.; Dunmore, J.; Scheffel, K.; Stetler, C.; Davis, M.; Dickson, D.; Jarpe, M.; DeTure, M.; et al. Acetylation of the KXGS motifs in tau is a critical determinant in modulation of tau aggregation and clearance. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzwa, S.A.; Shan, X.; Macauley, M.S.; Clark, T.; Skorobogatko, Y.; Vosseller, K.; Vocadlo, D.J. Increasing O-GlcNAc slows neurodegeneration and stabilizes tau against aggregation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzwa, S.A.; Cheung, A.H.; Okon, M.; McIntosh, L.P.; Vocadlo, D.J. O-GlcNAc Modification of tau Directly Inhibits Its Aggregation without Perturbing the Conformational Properties of tau Monomers. J. Mol. Biol. 2014, 426, 1736–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamblin, T.C.; Chen, F.; Zambrano, A.; Abraha, A.; Lagalwar, S.; Guillozet, A.L.; Lu, M.; Fu, Y.; Garcia-Sierra, F.; Lapointe, N.; et al. Caspase cleavage of tau: Linking amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 10032–10037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Gu, J.-H.; Miao, J.; Wu, F.; Liu, F. Tau truncation in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: A narrative review. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 19, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-L.; Wang, N.; Sun, F.-R.; Cao, X.-P.; Zhang, W.; Yu, J.-T. Tau in neurodegenerative disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benilova, I.; Gallardo, R.; Ungureanu, A.-A.; Cano, V.C.; Snellinx, A.; Ramakers, M.; Bartic, C.; Rousseau, F.; Schymkowitz, J.; De Strooper, B. The Alzheimer Disease Protective Mutation A2T Modulates Kinetic and Thermodynamic Properties of Amyloid-β (Aβ) Aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 30977–30989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naudi-Fabra, S.; Tengo, M.; Jensen, M.R.; Blackledge, M.; Milles, S. Quantitative Description of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Using Single-Molecule FRET, NMR, and SAXS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 20109–20121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metskas, L.A.; Rhoades, E. Single-Molecule FRET of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2020, 71, 391–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sil, S.; Datta, I.; Basu, S. Use of AI-methods over MD simulations in the sampling of conformational ensembles in IDPs. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1542267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvin, M.T.; Silvers, R.; Ni, Q.Z.; Can, T.V.; Sergeyev, I.; Rosay, M.; Donovan, K.J.; Michael, B.; Wall, J.; Linse, S.; et al. Atomic Resolution Structure of Monomorphic Aβ42 Amyloid Fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 9663–9674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Yau, W.-M.; Louis, J.M.; Tycko, R. Structures of brain-derived 42-residue amyloid-β fibril polymorphs with unusual molecular conformations and intermolecular interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2218831120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozohanics, O.; Ambrus, A. Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry: A Novel Structural Biology Approach to Structure, Dynamics and Interactions of Proteins and Their Complexes. Life 2020, 10, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetaloo, N.; Zacharopoulou, M.; Stephens, A.D.; Schierle, G.S.K.; Phillips, J.J. Millisecond Hydrogen/Deuterium-Exchange Mass Spectrometry Approach to Correlate Local Structure and Aggregation in α-Synuclein. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 16711–16719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Desai, A.A.; Zupancic, J.M.; Smith, M.D.; Tessier, P.M.; Ruotolo, B.T. Native ion mobility-mass spectrometry reveals the binding mechanisms of anti-amyloid therapeutic antibodies. Protein Sci. 2024, 33, e5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, S.; Surewicz, W.K. Tau liquid–liquid phase separation in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Cell Biol. 2022, 32, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainani, H.; Bouchmaa, N.; Ben Mrid, R.; El Fatimy, R. Liquid-liquid phase separation of protein tau: An emerging process in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 178, 106011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, O.M.; Toprakcioglu, Z.; Röntgen, A.; Cali, M.; Knowles, T.P.J.; Vendruscolo, M. Aggregation of the amyloid-β peptide (Aβ40) within condensates generated through liquid–liquid phase separation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šneiderienė, G.; Díaz, A.G.; Das Adhikari, S.; Wei, J.; Michaels, T.; Šneideris, T.; Linse, S.; Vendruscolo, M.; Garai, K.; Knowles, T.P.J. Lipid-induced condensate formation from the Alzheimer’s Aβ peptide triggers amyloid aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2401307122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Sun, H.; Cai, Q.; Tai, H.-C. The Enigma of Tau Protein Aggregation: Mechanistic Insights and Future Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejedor, A.R.; Collepardo-Guevara, R.; Ramírez, J.; Espinosa, J.R. Time-Dependent Material Properties of Aging Biomolecular Condensates from Different Viscoelasticity Measurements in Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 4441–4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Kim, T.H.; Das, S.; Pal, T.; Wessén, J.; Rangadurai, A.K.; Kay, L.E.; Forman-Kay, J.D.; Chan, H.S. Electrostatics of salt-dependent reentrant phase behaviors highlights diverse roles of ATP in biomolecular condensates. eLife 2025, 13, RP100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhong, D.; Hou, S. Study liquid–liquid phase separation with optical microscopy: A methodology review. APL Bioeng. 2023, 7, 021502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; de Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr. CHARMM36m: An improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robustelli, P.; Piana, S.; Shaw, D.E. Developing a molecular dynamics force field for both folded and disordered protein states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E4758–E4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, J.; Skepö, M. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: On the Accuracy of the TIP4P-D Water Model and the Representativeness of Protein Disorder Models. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 3407–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, M.K.; Månsson, L.K.; Meklesh, V.; Persson, P.; Skepö, M. Molecular dynamics simulations of the adsorption of an intrinsically disordered protein: Force field and water model evaluation in comparison with experiments. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 958175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.-P.; Chen, J.; Van Voorhis, T. Systematic Parametrization of Polarizable Force Fields from Quantum Chemistry Data. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.-P.; Martinez, T.J.; Pande, V.S. Building Force Fields: An Automatic, Systematic, and Reproducible Approach. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 1885–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polêto, M.D.; Lemkul, J.A. Integration of experimental data and use of automated fitting methods in developing protein force fields. Commun. Chem. 2022, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fass, J.; Kaminow, B.; Herr, J.E.; Rufa, D.; Zhang, I.; Pulido, I.; Henry, M.; Macdonald, H.E.B.; Takaba, K.; et al. End-to-end differentiable construction of molecular mechanics force fields. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 12016–12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenholz, S.S.; Cubuk, E.D. JAX, MD A framework for differentiable physics*. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2021, 2021, 124016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaba, K.; Friedman, A.J.; Cavender, C.E.; Behara, P.K.; Pulido, I.; Henry, M.M.; MacDermott-Opeskin, H.; Iacovella, C.R.; Nagle, A.M.; Payne, A.M.; et al. Machine-learned molecular mechanics force fields from large-scale quantum chemical data. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 12861–12878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.C.T.; Alessandri, R.; Barnoud, J.; Thallmair, S.; Faustino, I.; Grünewald, F.; Patmanidis, I.; Abdizadeh, H.; Bruininks, B.M.H.; Wassenaar, T.A.; et al. Martini 3: A general purpose force field for coarse-grained molecular dynamics. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasen, F.E.; Skaalum, T.; Kumar, A.; Srinivasan, S.; Vanni, S.; Lindorff-Larsen, K. Rescaling protein-protein interactions improves Martini 3 for flexible proteins in solution. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Brasnett, C.; Borges-Araújo, L.; Souza, P.C.T.; Marrink, S.J. Martini3-IDP: Improved Martini 3 force field for disordered proteins. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, J.A.; Reinhardt, A.; Aguirre, A.; Chew, P.Y.; Russell, K.O.; Espinosa, J.R.; Garaizar, A.; Collepardo-Guevara, R. Physics-driven coarse-grained model for biomolecular phase separation with near-quantitative accuracy. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2021, 1, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesei, G.; Lindorff-Larsen, K. Improved predictions of phase behaviour of intrinsically disordered proteins by tuning the interaction range. Open Res. Eur. 2023, 2, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauh, A.S.; Tesei, G.; Lindorff-Larsen, K. A coarse-grained model for disordered proteins under crowded conditions. Protein Sci. 2025, 34, e70232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottaro, S.; Bengtsen, T.; Lindorff-Larsen, K. Integrating Molecular Simulation and Experimental Data: A Bayesian/Maximum Entropy Reweighting Approach. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2112, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomi, M.; Camilloni, C.; Cavalli, A.; Vendruscolo, M. Metainference: A Bayesian inference method for heterogeneous systems. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomi, M.; Camilloni, C.; Vendruscolo, M. Metadynamic metainference: Enhanced sampling of the metainference ensemble using metadynamics. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, D.M.; Chong, L.T. Weighted Ensemble Simulation: Review of Methodology, Applications, and Software. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2017, 46, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J.D.; Zhang, S.; Leung, J.M.G.; Bogetti, A.T.; Thompson, J.P.; DeGrave, A.J.; Torrillo, P.A.; Pratt, A.J.; Wong, K.F.; Xia, J.; et al. WESTPA 2.0: High-Performance Upgrades for Weighted Ensemble Simulations and Analysis of Longer-Timescale Applications. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2022, 18, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elber, R. Milestoning: An Efficient Approach for Atomically Detailed Simulations of Kinetics in Biophysics. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2020, 49, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, S.; Narayan, B.; Elber, R.; Wong, C.F. Milestoning simulation of ligand dissociation from the glycogen synthase kinase 3β. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2023, 91, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Friesner, R.A.; Berne, B.J. Replica Exchange with Solute Scaling: A More Efficient Version of Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering (REST2). J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 9431–9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Arantes, P.R.; Bhattarai, A.; Hsu, R.V.; Pawnikar, S.; Huang, Y.M.; Palermo, G.; Miao, Y. Gaussian accelerated molecular dynamics (GaMD): Principles and applications. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2021, 11, e1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Y.; Feher, V.A.; McCammon, J.A. Gaussian Accelerated Molecular Dynamics: Unconstrained Enhanced Sampling and Free Energy Calculation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 3584–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.-H.; Ojha, A.A.; Amaro, R.E.; McCammon, J.A. Gaussian-Accelerated Molecular Dynamics with the Weighted Ensemble Method: A Hybrid Method Improves Thermodynamic and Kinetic Sampling. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 7938–7951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovalov, K.A.; Unarta, I.C.; Cao, S.; Goonetilleke, E.C.; Huang, X. Markov State Models to Study the Functional Dynamics of Proteins in the Wake of Machine Learning. JACS Au 2021, 1, 1330–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thody, S.A.; Clements, H.D.; Baniasadi, H.; Lyon, A.S.; Sigman, M.S.; Rosen, M.K. Small-molecule properties define partitioning into biomolecular condensates. Nat. Chem. 2024, 16, 1794–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. Predicting small-molecule partitioning. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2024, 20, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgore, H.R.; Mikhael, P.G.; Overholt, K.J.; Boija, A.; Hannett, N.M.; Van Dongen, C.; Lee, T.I.; Chang, Y.-T.; Barzilay, R.; Young, R.A. Distinct chemical environments in biomolecular condensates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2024, 20, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgore, H.R.; Young, R.A. Learning the chemical grammar of biomolecular condensates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022, 18, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stank, A.; Kokh, D.B.; Horn, M.; Sizikova, E.; Neil, R.; Panecka, J.; Richter, S.; Wade, R.C. TRAPP webserver: Predicting protein binding site flexibility and detecting transient binding pockets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W325–W330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmanic, A.; Bowman, G.R.; Juarez-Jimenez, J.; Michel, J.; Gervasio, F.L. Investigating Cryptic Binding Sites by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Accounts Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.-H.; Krishnan, V.V. Identification of ligand binding sites in intrinsically disordered proteins with a differential binding score. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, A.; Sisk, T.R.; Robustelli, P. Ensemble Docking for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 6847–6860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mey, A.S.J.S.; Allen, B.K.; Macdonald, H.E.B.; Chodera, J.D.; Hahn, D.F.; Kuhn, M.; Michel, J.; Mobley, D.L.; Naden, L.N.; Prasad, S.; et al. Best Practices for Alchemical Free Energy Calculations [Article v1.0]. Living J. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2020, 2, 18378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gapsys, V.; Yildirim, A.; Aldeghi, M.; Khalak, Y.; van der Spoel, D.; de Groot, B.L. Accurate absolute free energies for ligand–protein binding based on non-equilibrium approaches. Commun. Chem. 2021, 4, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Nussinov, R.; Ma, B. Mechanisms of recognition of amyloid-β (Aβ) monomer, oligomer, and fibril by homologous antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 18325–18343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; van Dyck, C.H.; Gee, M.; Doherty, T.; Kanekiyo, M.; Dhadda, S.; Li, D.; Hersch, S.; Irizarry, M.; Kramer, L.D. Lecanemab Clarity AD: Quality-of-Life Results from a Randomized, Double-Blind Phase 3 Trial in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 10, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderberg, L.; Johannesson, M.; Nygren, P.; Laudon, H.; Eriksson, F.; Osswald, G.; Möller, C.; Lannfelt, L. Lecanemab, Aducanumab, and Gantenerumab—Binding Profiles to Different Forms of Amyloid-Beta Might Explain Efficacy and Side Effects in Clinical Trials for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, C.J.; Zhang, Y.; Dhadda, S.; Wang, J.; Kaplow, J.; Lai, R.Y.K.; Lannfelt, L.; Bradley, H.; Rabe, M.; Koyama, A.; et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase 2b proof-of-concept clinical trial in early Alzheimer’s disease with lecanemab, an anti-Aβ protofibril antibody. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2021, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremic, D.; Navarro-López, J.D.; Jiménez-Díaz, L. Efficacy and safety of anti-amyloid-β monoclonal antibodies in current Alzheimer’s disease phase III clinical trials: A systematic review and interactive web app-based meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 90, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaka, H.; Nishida, K.; Kanazawa, T. Beyond lecanemab: Examining Phase III potential in Alzheimer’s therapeutics. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. Rep. 2024, 3, e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhattacharya, K.; Khanal, P.; Chand, J.; Chanu, N.R.; Das, D.; Bhattacharjee, A. Druggable Ensembles of Aβ and Tau: Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Biophysics, Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation and Multiscale Modeling for Alzheimer’s. Biophysica 2025, 5, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040052

Bhattacharya K, Khanal P, Chand J, Chanu NR, Das D, Bhattacharjee A. Druggable Ensembles of Aβ and Tau: Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Biophysics, Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation and Multiscale Modeling for Alzheimer’s. Biophysica. 2025; 5(4):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040052

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhattacharya, Kunal, Pukar Khanal, Jagdish Chand, Nongmaithem Randhoni Chanu, Dibyajyoti Das, and Atanu Bhattacharjee. 2025. "Druggable Ensembles of Aβ and Tau: Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Biophysics, Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation and Multiscale Modeling for Alzheimer’s" Biophysica 5, no. 4: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040052

APA StyleBhattacharya, K., Khanal, P., Chand, J., Chanu, N. R., Das, D., & Bhattacharjee, A. (2025). Druggable Ensembles of Aβ and Tau: Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Biophysics, Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation and Multiscale Modeling for Alzheimer’s. Biophysica, 5(4), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040052