Abstract

This study analyzes the development and characterization of hybrid polyurethane composites reinforced with agro-industrial residues of Arundo donax and recycled polyurethane. Formulations were prepared with different reinforcement concentrations (10%, 15%, and 20%) and alkaline treatments (0%, 5%, and 10% NaOH). Their mechanical performance was evaluated through tensile and flexural tests, while their thermal behavior was assessed via thermal conductivity measurements. The results revealed that the formulation containing 15% reinforcement and a 5% alkaline treatment (B2) achieved the highest flexural strength (0.58 MPa), indicating efficient interfacial interaction between the fibers and the matrix. Furthermore, all reinforced formulations exhibited lower thermal conductivity values than the unreinforced polyurethane (0.166 W/m·°C), confirming their potential as thermal insulation materials. These findings demonstrate the feasibility of utilizing lignocellulosic and polymeric residues to produce sustainable bio-composites, contributing to the development of materials with enhanced mechanical and thermal properties and promoting the circular economy.

1. Introduction

The sustained growth of the global population, together with increasing industrialization and consumption, has exerted considerable pressure on natural resources, leading to an exponential rise in the generation of both urban and industrial solid waste [1]. This challenge has driven the development of technologies that promote environmental sustainability, circular economy principles, and the efficient use of available resources [2]. In this context, the design and manufacture of composite materials that incorporate both lignocellulosic and polymeric waste represent a promising alternative, particularly for applications requiring high-performance materials with low environmental impact [3,4,5].

Polymer matrix composites reinforced with natural fibers have attracted significant interest within the scientific community due to their ecological advantages, low cost, and favorable mechanical performance [5]. Since ancient times, plant fibers have been used to reinforce construction materials, textiles, and tools. However, in recent decades, advances in materials science have enabled systematic studies of these fibers as reinforcing elements in synthetic matrices, particularly in thermoset and thermoplastic polymers [6]. Recent research has demonstrated that natural fiber-reinforced composites can achieve mechanical properties comparable to those of conventional synthetic materials, with the additional advantage of being biodegradable or recyclable [3].

The utilization of lignocellulosic residues derived from underutilized or invasive plant species constitutes a sustainable strategy from both environmental and economic perspectives [6]. One such species is Arundo donax (giant reed), a plant characterized by rapid growth, high biomass yield, and great adaptability, which has been classified as invasive in various regions worldwide. Despite its favorable morphological and physicochemical characteristics, such as high cellulose content and low density, its industrial application remains limited, resulting in the accumulation of unexploited residues [7,8]. The valorization of Arundo donax as a reinforcement material in polymer composites represents a viable strategy to mitigate its environmental impact while opening new application possibilities in sectors such as construction, automotive, and furniture manufacturing.

Polyurethane (PU), on the other hand, is a polymer widely used across multiple industries due to its versatility, which allows the production of materials with diverse properties, from flexible and rigid foams to elastomers and coatings [9]. However, its resistance to degradation and complex molecular structure hinder recycling and final disposal, making it an increasingly significant environmental concern [10,11]. In this regard, the reintegration of processed polyurethane waste into new composite matrices emerges as an innovative solution that not only reduces waste volume but also enables the development of materials with improved characteristics, leveraging the chemical and structural compatibility between components [12].

This study proposes to develop hybrid polyurethane matrix composites reinforced with Arundo donax (giant reed) fiber residues and processed polyurethane waste, with the aim of evaluating their mechanical behavior and viability as alternative materials for industrial applications. The approach combines two waste valorization strategies: on the one hand, the use of a non-conventional plant fiber with high lignocellulosic content, and on the other, the recycling of a post-consumer polymer, thereby promoting an integrated approach to waste utilization. The study encompasses the preparation of Arundo donax fibers through cleaning, drying, and conditioning processes, the incorporation of recycled polyurethane particles into the mixture, and the characterization of the final material in terms of its physical, morphological, and mechanical properties. In this way, the study seeks to identify the synergistic potential between both types of reinforcement and their effect on the polymer matrix.

Unlike previous studies that relied on common natural fibers such as bamboo, sisal, or kenaf, the present work is the first to simultaneously incorporate Arundo donax residues and processed polyurethane waste into a virgin polyurethane matrix. This hybrid reinforcement approach specifically investigates the synergistic effects on the mechanical and thermal performance of the resulting material.

The novelty of this study lies not only in the use of an underutilized and highly valorizable lignocellulosic fiber derived from an invasive species, but also in the integration of processed polymeric waste as a co-reinforcement, thereby introducing a new strategy for sustainable composite design. Recent characterization studies have highlighted the strong reinforcement potential of Arundo donax fibers, which exhibit high cellulose content (≈70%), good thermal stability, tensile strength approaching 900 MPa, and an elastic modulus of approximately 42 GPa—values comparable or superior to those of conventional natural fibers such as sisal or kenaf [13]. Investigations of Arundo donax in other polymer systems, including polylactic acid (PLA) and polyethylene (PE) composites, have further confirmed its ability to significantly modify mechanical, thermal, and degradation behavior, although fiber–matrix adhesion and porosity remain critical challenges that require careful control [14].

By combining these two waste-derived reinforcements, the resulting hybrid composite offers improved performance while addressing two distinct environmental problems: the uncontrolled spread of an invasive plant species and the accumulation of post-industrial polyurethane waste. This dual-valorization strategy simultaneously expands the range of raw materials available to the polymer composites industry and promotes the use of local, underutilized biomass as a strategic resource for sustainable development [15,16].

In this context, the present research is highly relevant because it not only contributes to the valorization of lignocellulosic and plastic waste but also drives the development of alternative materials with lower environmental impact and high industrial applicability. It is expected that such hybrid composites will facilitate the transition toward more circular and sustainable production models, broadening opportunities to substitute non-renewable resources with local and renewable alternatives. They also offer a clear pathway for future quantitative life-cycle assessments (LCA) to fully quantify embodied energy and CO2 savings. Moreover, this work aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 15 (Life on Land), by promoting technological innovation, efficient resource utilization, and the sustainable management of invasive species. Although the thermal conductivity obtained is higher than that of conventional commercial insulation materials, the developed material is intended for non-critical applications where sustainability and the use of agro-industrial residues are the main priorities. These applications include interior panels, ecological coatings, low-thermal-demand components, and bio-based alternatives within construction systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

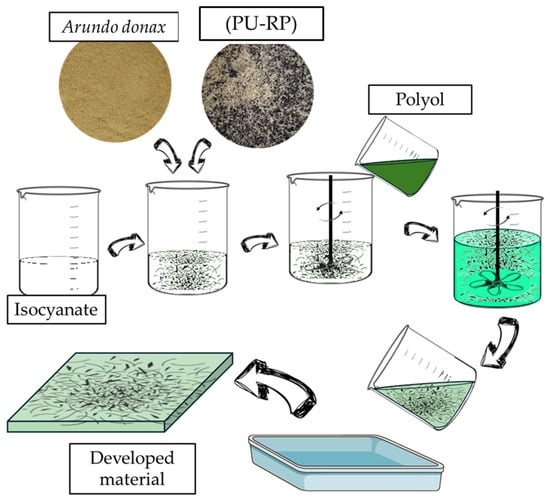

The Giant reed (Arundo donax) fibers used in this study were obtained as by-products from the production of radial basketry crafts in the Valle de Tenza region, Boyacá, Colombia. The reeds, with an average age of 18 months, were treated by immersion in a boric acid and borax solution (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), following the specifications established in ISO 22156 [17,18]. Crucially, before incorporation into the matrix, the Arundo donax fibers were sieved and used at a size fraction of 2 mm or smaller. Recycled polyurethane particles (PU-RP), size-reduced to <2 mm, were also incorporated. These particles were obtained as post-industrial polyurethane waste from the company Espumol (Boyacá, Colombia).

The resin employed as the matrix of the composite was a bio-based polyurethane (PU) derived from Ricinus communis (castor oil). This resin was commercially acquired from the company Imperveg, marketed as IMPERVEG® UG 132 A (Aguaí, SP, Brazil). The polyurethane was prepared as follows: the polyol was kept in a liquid state until the initiator (isocyanate) was added at a mass ratio of 1.1:1 (isocyanate/polyol), corresponding to the specific NCO/OH index specified by the manufacturer.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Extraction of Giant Reed Fibers (Arundo donax)

Fiber extraction was performed using a mechanical grinder manufactured by Hamilton Beach (Glen Allen, VA, USA). The grinding device was equipped with four blades rotating at 1200 rpm, enabling the separation of fiber bundles approximately 8 cm in length. These bundles were then cut using a metal paper guillotine to obtain fibers up to 2 mm in length.

For surface modification, an alkaline treatment was applied. Three NaOH concentrations were used for this process: 0%, 5%, and 10%, with an exposure time of 8 h, a duration selected based on literature reports indicating optimal lignin and hemicellulose removal in similar lignocellulosic fibers. The treated fibers were subsequently washed repeatedly with distilled water until the pH of the wash water reached neutrality (pH ≈ 7). They were then air-dried at room temperature (20 °C) until constant mass was achieved.

2.2.2. Fabrication of Composite Materials

Composites reinforced with Arundo donax fiber and (PU-RP) were fabricated at reinforcement levels of 10%, 15%, and 20% by weight, using three NaOH treatment concentrations (0%, 5%, and 10%), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental design of the developed materials.

The samples were prepared by inserting short Arundo donax fibers and (PU-RP) in a 1:1 ratio, together with the pre-mixed isocyanate. Once homogenized, the polyol was added, and the mixture was stirred at 800 rpm for 20 s at an ambient temperature of 20 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 50 ± 5% before being poured into a metallic mold. The composite preparation was conducted in a metal mold with final closed dimensions of 180 × 140 × 3 mm. The mold was then sealed and subjected to a pressure of 2 MPa in a hydraulic press to consolidate the material and control apparent density. It was left for 36 h at room temperature (20 °C) before demolding and post-curing for 7 days. It is important to note that the initial 36 h correspond only to the period prior to demolding. All formulations were subsequently subjected to a full 7-day curing process, and only after this period were the mechanical and thermal tests performed, ensuring that all materials shared the same curing history.

Figure 1 shows the process of obtaining the plates of the developed material.

Figure 1.

Process of obtaining the plates of the developed material.

After the curing period, composite plates with dimensions of 180 × 140 × 3 mm3 (dimensions of the closed mold) were obtained. The quantities of fibers used for each developed material were calculated based on weight. Table 2 presents the weight percentages of each component used in the development of the composite materials at reinforcement levels of 10%, 15%, and 20%.

Table 2.

Percentage composition of the developed materials.

Subsequently, the plates were cut using a laser cutter to obtain specimens for each test (tensile and flexural strength). Composites reinforced with 10%, 15%, and 20% by weight of Arundo donax fiber and (PU-RP) were fabricated, along with unreinforced polyurethane samples, in order to compare the results obtained for the composites with a control sample.

The 20% fiber-reinforced composite represented the maximum reinforcement content that could be incorporated into the PU resin, as higher concentrations made mixing and mold casting difficult. The 10% by-weight formulation exhibited the best handling and flow behavior during mold casting.

The selected reinforcement percentages (10%, 15%, and 20%) were established based on preliminary tests indicating that loadings below 10% did not produce significant variations in the thermal properties, whereas values above 20% hindered mixing and mold filling due to increased viscosity. The 0% level was used solely as the control sample (unreinforced PU).

2.2.3. Determination of the Apparent Density

The apparent density (ρ) of the formulations was determined using the gravimetric mass/volume method, in accordance with ASTM D792-20 [19]. Specimens were oven-dried at 60 °C for 24 h and weighed with an analytical balance (±0.001 g). Specimen volume was calculated from dimensions measured with a digital caliper (30 × 30 × 3 mm). Density was calculated as ρ = m/V. Five replicates per formulation were evaluated; mean values and standard deviations are reported.

2.2.4. Mechanical Characterization of the Developed Materials

Tensile strength and three-point flexural strength tests were selected in order to determine the mechanical properties of the developed materials.

The tensile strength tests were conducted in accordance with ASTM D638 [20]. Experiments were performed using a WDW100 UTM universal testing machine (Jinan Hensgrand Instrument Co., Ltd., Jinan, China) equipped with a 5 kN load cell, operating at a constant crosshead speed of 1 mm/min and an ambient temperature of approximately 20 °C. Each material was tested using five specimens, which were loaded to fracture.

The three-point flexural strength tests were also conducted using a WDW100 UTM universal testing machine (Jinan Hensgrand Instrument Co., Ltd., Jinan, China) equipped with a 5 kN load cell. The crosshead speed was set to 1 mm/min, and the specimens had dimensions of 127 × 12.7 × 3 mm3, following the ASTM D790-17 [21]. Considering the specimen thickness (3 mm), a support span of 48 mm was established (applying the 16:1 ratio), following the common practice for this standard. Each test was performed on five specimens per material, continuing until fracture or until a 5% deformation was observed.

2.2.5. Thermal Conductivity

This study was conducted in accordance with the ASTM D5334-08 [22]. Cylindrical samples with a diameter of 100 mm and a height of 10 mm were subjected to an experimental curing process lasting up to 7 days. After curing, the samples underwent an extensive drying process in an oven until a constant weight was achieved, followed by cooling to room temperature (20 °C) and were maintained at this temperature until the thermal test to ensure thermal stability. The thermal conductivity of the samples was then measured using a KD2 Pro Thermal Conductivity Meter (Decagon Devices, Inc., Pullman, WA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Apparent Density

The apparent density of the composites was determined gravimetrically according to ASTM D792. Mean values and standard deviations are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Apparent Density of the Developed Formulations.

The formulations displayed apparent densities ranging from 0.287 to 0.420 g/cm3. Sample B2 exhibited the highest density (0.412 g/cm3), which aligns with its maximum flexural strength value and indicates greater internal compactness and reduced porosity. This behavior supports the direct relationship between apparent density and structural stiffness in cellular materials and polymer-matrix composites. Likewise, the C-series samples showed higher densities than the A-series, which is consistent with the increased amount of reinforcement incorporated.

3.2. Flexural Strength

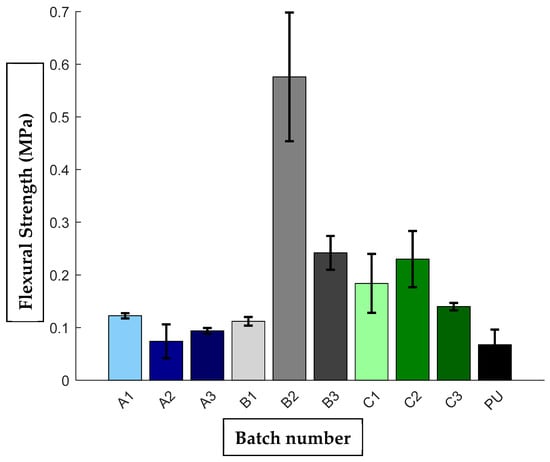

Figure 2 presents the flexural strength values obtained for both the developed materials and the unreinforced polyurethane. As can be observed, the flexural strength of the materials varies according to the content and treatment of the Giant reed fiber when used as reinforcement within the polyurethane matrix.

Figure 2.

Flexural strength of the developed materials compared to unreinforced polyurethane.

The figure shows the average flexural strength values (MPa) obtained for the different experimental groups (A1, A2, A3, B1, B2, B3, C1, C2, C3, and PU). In general, the values range between 0.07 and 0.58 MPa. It noteworthy that these low values, when compared with the literature for structural composites, are consistent with the low apparent density of the material. This suggests an application primarily in the field of thermal insulation rather than load-bearing structures.

Among the results, group B2 showed the highest flexural strength, reaching approximately 0.58 MPa. Groups B3 and C2 exhibited intermediate resistance levels (0.23 ± 0.02 and 0.25 ± 0.03 MPa, respectively), with moderate standard deviations suggesting a more stable behavior compared to B2. These intermediate values indicate that, although they do not reach the maximum strength observed in B2, they present better repeatability in terms of mechanical performance.

Groups C1 and C3 displayed low strength values (0.14–0.18 MPa), with C1 showing a relatively high dispersion. This suggests that the conditions associated with this group did not provide sufficient structural reinforcement to the material. Finally, the PU group exhibited the lowest resistance (~0.07 MPa), accompanied by significant variability relative to its mean, confirming its limited ability to withstand flexural stress.

In comparison, the groups from series A (A1, A2, A3) also demonstrated very low strength values (0.07–0.12 MPa). The similarity among their results indicates that the modifications applied to this set of samples did not produce substantial improvements in flexural behavior.

Overall, these findings indicate that series B, particularly group B2, exhibits the best mechanical performance under flexural conditions. Series A and PU are the least resistant, while series C represents an intermediate range, with moderate strength values and greater consistency than B2.

3.3. Tensile Strength

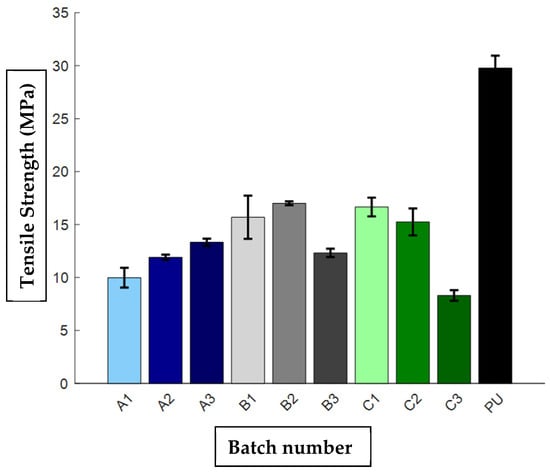

Figure 3 shows the average tensile strength values (MPa) obtained for the different study groups. It can be observed that the tensile strength results range approximately between 9 and 30 MPa, demonstrating marked differences in the mechanical behavior of the evaluated materials.

Figure 3.

Tensile strength of the developed materials compared to unreinforced polyurethane.

Regarding tensile strength, the reinforced materials displayed values between 9 and 17 MPa, while the unreinforced polyurethane reached approximately 30 MPa. This outcome contradicts the common reinforcement effect, highlighting that the incorporation of the hybrid filler primarily serves as a lightweight filler to enhance thermal insulation, rather than a load-bearing reinforcement for tensile applications.

The PU group exhibited the highest tensile strength (~30 MPa), with relatively low dispersion, indicating consistent performance. In contrast, the series A groups (A1, A2, A3) showed the lowest values, ranging from 10 to 13 MPa, placing them among the weakest materials in the set.

Series B and C presented intermediate results. Specifically, B1 and B2 reached values of approximately 16–17 MPa, while B3 decreased to around 12 MPa. The C series showed more variability: C1 reached a tensile strength of about 17 MPa, C2 was close to 15 MPa, and C3 dropped significantly to roughly 9 MPa, similar to the lowest values observed in series A.

3.4. Thermal Conductivity

The thermal conductivity (λ) of the polyurethane formulations reinforced with agro-industrial residues was determined using a KD2 Pro Thermal Properties Analyzer (Decagon Devices, Pullman, WA, USA), which operates based on the transient hot-wire method. Measurements were performed using the single-needle TR-1 sensor (Merit Sensor, South Jordan, UT, USA), suitable for solid materials, with an operational range of 0.1–4.0 W/m·°C and an accuracy of ±10%.

Each sample was analyzed in duplicate, ensuring prior thermal equilibrium and proper contact between the sensor and the material through the application of a thermally conductive grease. Measurements were carried out under controlled ambient conditions (23–25 °C) to ensure thermal stability of the specimens during data collection.

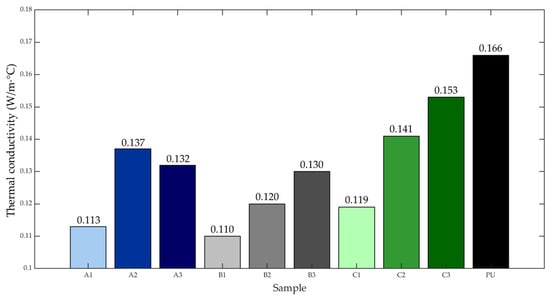

The results show that the reinforced formulations exhibited lower thermal conductivity values than the unreinforced polyurethane. Series A recorded values ranging from 0.113 to 0.137 W/m·°C, series B ranged from 0.110 to 0.130 W/m·°C, and series C from 0.119 to 0.153 W/m·°C. The highest value corresponded to the base polyurethane (PU), with 0.166 W/m·°C.

Figure 4 presents the average thermal conductivity (λ) values obtained for the different formulations of polyurethane reinforced with agro-industrial residues, as well as for unreinforced polyurethane (PU). Measurements were carried out at room temperature (23–25 °C).

Figure 4.

Thermal conductivity of the developed materials.

The λ values ranged from 0.110 to 0.166 W/m·°C, confirming the thermal insulating nature of the evaluated materials. It was observed that the reinforced formulations generally exhibited lower thermal conductivity values compared to the base polyurethane.

The values in series A increased progressively from 0.113 to 0.137 W/m·°C, reaching a maximum in sample A2, while A3 showed a slight reduction (0.132 W/m·°C). Series B recorded intermediate values between 0.110 and 0.130 W/m·°C, with gradual increments among the formulations. Series C displayed the highest values among the reinforced composites, reaching 0.153 W/m·°C in sample C3. Finally, unreinforced polyurethane (PU) showed the highest overall thermal conductivity (0.166 W/m·°C).

The results indicate that the incorporation of agro-industrial residues alters the thermal response of the material, with slight variations depending on the formulation. The low data dispersion (±0.003 W/m·°C) demonstrates good experimental repeatability and thermal stability during testing. The high repeatability of measurements, with standard deviations below 3%, further confirms the precision of the method used and the adequate thermal stability of the samples during the experiment, suggesting that the observed differences in λ values among the formulations are statistically representative of the material variations.

4. Discussion

The incorporation of Arundo donax (giant reed) fibers and (PU-RP) residues significantly modified the mechanical and thermal properties of the polyurethane matrix. The results obtained demonstrate that both the reinforcement percentage and the alkaline treatment applied play a decisive role in the tensile strength, flexural strength, and thermal conductivity of the composites.

In the flexural strength tests, the values ranged from 0.07 to 0.58 MPa, with formulation B2 (15% reinforcement, 5% NaOH treatment) showing the highest resistance. In contrast, series A and the pure polyurethane (PU) exhibited lower values, indicating reduced structural rigidity and less efficient fiber–matrix adhesion. This trend may be attributed to better reinforcement dispersion and a potentially optimized interface in series B, which could promote more uniform stress transfer within the matrix.

These findings are consistent with those of Pattnaik et al. [2], who reported that polyurethane foams reinforced with natural fibers reach an optimal strength point at around 15% loading. Exceeding this threshold produces interfacial defects and voids that reduce mechanical integrity, a phenomenon also observed in samples A3, B3, and C3.

Regarding tensile strength, the reinforced materials exhibited values between 9 and 17 MPa, while the unreinforced polyurethane reached approximately 30 MPa. This overall reduction is related to the partial incompatibility between the hydrophobic polymeric matrix and the hydrophilic surface of lignocellulosic fibers, as well as the formation of micro-defects at the interface, which act as stress concentration zones.

This behavior aligns with the findings of Ajayi et al. [6], who reported a progressive decrease in tensile strength as the natural fiber fraction exceeded 20%, due to a loss of interfacial cohesion. Similarly, Vishwash et al. [4] concluded that moderate alkaline treatments (≈5% NaOH) temporarily improve fiber–matrix adhesion by removing waxes and lignin, whereas higher concentrations damage the cell wall, reducing load transfer efficiency. This directly explains the lower mechanical values obtained for A3, B3, and C3.

Soni et al. [1] also highlighted that the random orientation of short fibers enhances ductility but limits specific tensile strength, consistent with the intermediate behavior observed in this study. Sample B2 exhibited higher strength, suggesting an optimal balance between reinforcement content and dispersion within the matrix, which is hypothesized to result in a more homogeneous microstructure.

Moreover, Hejna et al. [10] demonstrated that incorporating recycled polyurethane residues into virgin matrices slightly reduces strength but improves dimensional stability and energy absorption, reinforcing the idea that recycled material contributes to structural stabilization without compromising composite integrity.

Thermal conductivity values ranged from 0.110 to 0.166 W/m·°C, confirming the highly insulating character of the developed formulations. All reinforced samples exhibited lower values than the pure polyurethane (PU), attributable to the inherently low conductivity of lignocellulosic fibers, their porous structure, and the presence of interfacial regions that scatter heat flow.

These findings agree with those reported by Tiuc et al. [15], who observed similar reductions (~0.11 W/m·°C) in polyurethane foams reinforced with spruce sawdust, due to increased air content and interfacial thermal resistance. Likewise, Kamarudin et al. [16] demonstrated that the inclusion of natural fibers generates structural discontinuities that interrupt solid-state heat conduction, thereby reducing effective thermal transfer.

In this study, series B exhibited intermediate values (0.11–0.13 W/m·°C), whereas series C reached the highest among the reinforced composites (~0.153 W/m·°C). This can be explained by greater compaction and a lower air fraction in the C formulations, which increases solid-contact conduction, consistent with the findings of Mulla et al. [3]. Conversely, the unreinforced polyurethane (PU) displayed the highest thermal conductivity value (0.166 W/m·°C), typical of homogeneous and high-density materials, as also documented by Drzeżdżon and Datta [9].

Overall, the results suggest that the optimal composition corresponds to 15% reinforcement with a 5% NaOH alkaline treatment (sample B2), combining higher structural rigidity with low thermal conductivity. This balance is consistent with the trends reported by Pattnaik et al. [2] and Ajayi et al. [6], who emphasized the importance of controlling both fiber content and surface treatment to simultaneously optimize mechanical and thermal performance.

From a microstructural perspective, the observed improvement in flexural behavior and thermal stability is associated with a more uniform fiber distribution, moderate interfacial adhesion, and the presence of recycled polyurethane, which is hypothesized to act as a compatibilizing phase. The combination of these factors yields materials with a desirable balance between mechanical strength, thermal insulation, and environmental sustainability.

For future work, it is recommended to complement this analysis with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and multiscale thermal conduction modeling to specifically investigate the influence of reinforcement on apparent density and porosity, which are key determinants of conductivity. This approach will enable the correlation of cellular morphology and structural anisotropy with functional properties, and facilitate normalization of λ values, following the methods proposed by Mulla et al. [3] and Soni et al. [1].

5. Conclusions

The development of polyurethane composites reinforced with agro-industrial residues of Arundo donax yielded materials that exhibit a favorable combination of mechanical and thermal properties, particularly a significant reduction in thermal conductivity compared to the base polyurethane. The results demonstrate that the use of lignocellulosic reinforcements and (PU-RP) enables controlled modification of the material’s microstructure, directly influencing its stiffness, strength, and insulating capacity.

In the bending tests, formulation B2 (15% reinforcement and 5% alkaline treatment) exhibited the highest strength (0.58 MPa), indicating a more efficient stress transfer between the treated fibers and the matrix. Although the tensile strength was lower than that of the unreinforced polyurethane, the obtained values remained within acceptable ranges for structural bio-composites, confirming that the natural reinforcement enhances stiffness without excessively compromising the material’s integrity. Given the moderate mechanical performance, particularly the lower tensile strength, the material is primarily recommended for non-structural applications where thermal insulation is the primary requirement, such as an insulating coating or layer for conventional building materials.

Regarding thermal conductivity, the reinforced composites showed values between 0.110 and 0.153 W/m·°C, all lower than that of pure polyurethane (0.166 W/m·°C). This decrease is attributed to the low intrinsic conductivity of Arundo donax fibers, their porous structure, and the thermal discontinuity generated at the fiber–matrix interface, making these materials effective thermal insulators for applications in sustainable construction systems and energy-efficient solutions.

The combined analysis of the properties indicates that formulation B2 represents an optimal configuration, achieving an effective combination of maximum flexural strength, reduced thermal conductivity, and high dimensional stability. This performance is associated with a uniform dispersion of the reinforcement, stable interfacial adhesion, and the presence of (PU-RP), which acts as a compatibilizing phase between components. Due to its characteristics, this material is proposed for non-structural applications requiring low thermal conductivity, where the primary objective is to reduce the environmental impact through the use of lignocellulosic residues and (PU-RP).

In summary, the results confirm the technical and environmental potential of using Arundo donax agro-industrial residues as reinforcement in polyurethane matrices, contributing both to the valorization of agricultural by-products and to the reduction in polymer waste. Future work should focus on quantifying the eco-efficiency of the process, including metrics such as embodied energy and CO2 savings, to substantiate claims related to the circular economy and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.A.S.N. and A.F.R.-N.; methodology, A.F.R.-N. and E.Y.G.-P.; writing—review and editing, W.A.S.N.; supervision, G.B.T.; thermal analysis, K.P.C. and E.Y.G.-P.; project administration, E.Y.G.-P.; funding acquisition, G.B.T. and E.Y.G.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Códice SGI 4037 in the UPTC. Furthermore, the authors would like to thank the Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Soni, A.; Das, P.K.; Gupta, S.K.; Saha, A.; Rajendran, S.; Kamyab, H.; Yusuf, M. An overview of recent trends and future prospects of sustainable natural fiber-reinforced polymeric composites for tribological applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, S.S.; Behera, D.; Nanda, D.; Das, N.; Behera, A.K. Green chemistry approaches in materials science: Physico-mechanical properties and sustainable applications of grass fiber-reinforced composites. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 2629–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, M.H.; Norizan, M.N.; Rawi, N.F.M.; Kassim, M.H.M.; Abdullah, C.K.; Abdullah, N.; Norrrahim, M.N.F. A review of fire performance of plant-based natural fibre reinforced polymer composites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 141130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishwash, B.; Shivakumar, N.; Sachidananda, K. A brief review on natural fiber reinforced composite sandwich structures. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, M.M.; Alamry, K.A.; Hussein, M.A. Recent advances of Fiber-reinforced polymer composites for defense innovations. Results Chem. 2025, 15, 102199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, N.E.; Rusnakova, S.; Ajayi, A.E.; Ogunleye, R.O.; Agu, S.O.; Amenaghawon, A.N. A comprehensive review of natural fiber reinforced Polymer composites as emerging materials for sustainable applications. Appl. Mater. Today 2025, 43, 102666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, G.; Espigul, P.; Nogués, S.; Serrat, X. Arundo donax L. growth potential under different abiotic stress. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardion, L.; Verlaque, R.; Saltonstall, K.; Leriche, A.; Vila, B. Origin of the invasive Arundo donax (Poaceae): A trans-Asian expedition in herbaria. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drzeżdżon, J.; Datta, J. Advances in the degradation and recycling of polyurethanes: Biodegradation strategies, MALDI applications, and environmental implications. Waste Manag. 2025, 198, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hejna, A.; Barczewski, M.; Aniśko, J.; Piasecki, A.; Barczewski, R.; Kosmela, P.; Andrzejewski, J.; Szostak, M. Upcycling of medium-density fiberboard and polyurethane foam wastes into novel composite materials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2025, 25, 200244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, C.H.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Han, B.; Jae, W.S.; Lee, H.S.; Paik, H.-J.; Kim, I. Sustainable synthesis of waste soybean oil-based non-isocyanate polyurethane elastomers and foams. Polymer 2025, 323, 128217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reciclado Químico de Poliuretano: Nuevas vías Producción Polioles y Aminas Recicladas. Available online: https://itene.com/actualidad/reciclado-quimico-residuos-poliuretano (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Suárez, L.; Barczewski, M.; Kosmela, P.; Marrero, M.D.; Ortega, Z. Giant Reed (Arundo donax L.) Fiber Extraction and Characterization for Its Use in Polymer Composites. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 20, 2131687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, L.; Ortega, Z.; Romero, F.; Paz, R.; Marrero, M.D. Influence of Giant Reed Fibers on Mechanical, Thermal, and Disintegration Behavior of Rotomolded PLA and PE Composites. J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 30, 4848–4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiuc, A.-E.; Borlea, S.I.; Nemeș, O.; Vermeșan, H.; Vasile, O.; Popa, F.; Pințoi, R. New Composite Materials Made from Rigid/Flexible Polyurethane Foams with Fir Sawdust: Acoustic and Thermal Behavior. Polymers 2022, 14, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamarudin, S.H.; Basri, M.S.M.; Rayung, M.; Abu, F.; Ahmad, S.; Norizan, M.N.; Osman, S.; Sarifuddin, N.; Desa, M.S.Z.M.; Abdullah, U.H.; et al. A Review on Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites (NFRPC) for Sustainable Industrial Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preservación y Secado del Culmo de Guadua Angustifolia Kunth. Available online: https://tienda.icontec.org/gp-preservacion-y-secado-del-culmo-de-guadua-angustifolia-kunth-ntc5301-2018.html (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- UNE-ISO 22156:2024; Estructuras de Bambú. Tallos de Bambú. Cálculo Estructural. UNE: Madrid, Spain, 2024. Available online: https://www.une.org/encuentra-tu-norma/busca-tu-norma/norma?c=N0073192 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- ASTM D792-20; Standard Test Methods for Density and Specific Gravity (Relative Density) of Plastics by Displacement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D638-22; Método de Prueba Estándar D638 Para Propiedades de Tracción de Plásticos. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://store.astm.org/d0638-22.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- ASTM D790-17; Standard Test Methods for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D5334-22; Método de Prueba Estándar Para la Determinación de la Conductividad Térmica del Suelo y la Roca Mediante el Procedimiento de Sonda de Aguja Térmica. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://store.astm.org/d5334-22.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).