Abstract

Throughout the history of civil aviation, radio navigation aids have played a crucial role in ensuring the safety and continuity of air transportation. Although the development of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) over the past half-century has significantly improved positioning accuracy, the system’s vulnerability to interference considerably reduces its reliability and poses a risk to civil aviation safety. This limitation highlights the crucial role of ground-based radio navigation networks in ensuring nominal flight operations. This study presents a comprehensive analysis of the global coverage and performance of radio navigation aid networks and assesses the implementation level of Performance-Based Navigation (PBN) by Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs) worldwide. A novel methodology is proposed for network performance evaluation, incorporating spatial characteristics of parameter distribution across global airspace using a geospatial indexing framework to determine airspace configurations compliant with various area navigation (RNAV) specifications. The performance of DME/DME, VOR/DME, and VOR/VOR positioning methods is evaluated within the official ICAO regional airspace structure. The results indicate that the European and North American regions currently maintain the most developed DME and VOR networks and propose reliable infrastructure sustainability. Globally, RNAV 1 capability is supported within approximately 20.2% of airspace using DME/DME and 3.45% using VOR/DME, while RNAV 5 coverage extends over 23.61% of global airspace, which approves resource efficiency distribution. RNAV 10 coverage could be supported by the VOR/VOR positioning method only in 13.48% of global airspace. Overall, the obtained results confirm the limited positioning performance of VOR network compared with DME, supporting the continuation of VOR network rationalization strategies and highlighting the need for optimized resource sharing to ensure the resilience and safety of the global air navigation system.

1. Introduction

Civil aviation is grounded on stringent safety criteria to ensure the reliable and efficient provision of all air transportation services. Every aircraft operation must comply with an acceptable level of operational risk to maintain aviation safety [1]. Throughout a flight, each airspace user is required to adhere precisely to the cleared flight path. Any loss of navigation accuracy or significant deviation from the predefined trajectory poses a potential hazard not only to the airplane itself, but also to the surrounding air traffic. Consequently, air traffic management authorities can ensure the required level of flight safety only when all airspace users strictly follow their assigned (cleared) trajectories. It makes on-board navigation systems critical for the safety of civil aviation.

The level of airplane deviation from the cleared flight path results from errors of on-board positioning sensor and flight technique, which is identical to autopilot error in maintaining a planned flight path for the en-route phase of flight. To support accurate positioning and guidance, civil aviation employs a variety of radio navigation aids. These radio navigation aids are located outside of the airplane and operate with specific on-board equipment to identify the position of aircraft.

The core of radio navigation aids includes Distance Measuring Equipment (DME) operating in the UHF band, VHF Omnidirectional Range (VOR), Non-Directional Beacons (NDB), a Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), and an Instrument Landing System (ILS). Together, these systems form the backbone of modern air navigation infrastructure, enabling continuous, accurate, and safe flight operations across all phases of flight [2].

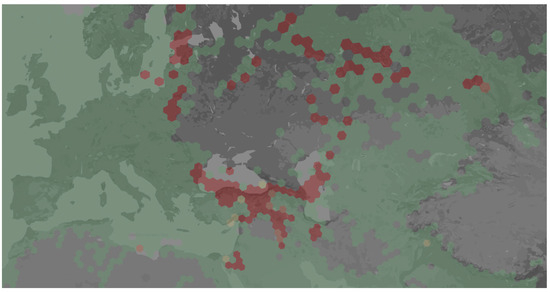

GNSS is the primary positioning sensor on-board of airplanes used in modern civil aviation [3]. Modern GNSS sensors use multiple constellations, leading to significant improvement in positioning accuracy. The highest accuracy of position measuring and being approximately constant around the globe parameters of availability and reliability made GNSS is leading system for precise navigation. However, GNSS is highly sensitive to interference actions [4,5]. As an example, unintentional jamming of GNSS caused 36 cases of on-board equipment malfunction during January–October 2025 in the US [6]. War in Ukraine and military activities in countries of the Middle East region caused significant unintentional jamming action in Eastern Europe (see Figure 1) [7,8]. Military jammers could affect wide areas due to the multipath effect and particularities of the relief geometry. It leads to strong GNSS jamming activity in regions around military actions [9,10]. This activity affects on-board GNSS receivers of civil airplanes and leads to its lock [11,12]. If the airplane is placed in an active jamming region for a short duration, the inertial navigation system could provide reliable navigation. In case of a long GNSS lock (commonly more than 7–10 min), a stand-by positioning algorithm by radio navigation aids should be initiated.

Figure 1.

Interference of GNSS signals over Europe on 16 October 2025. Source: Flightradar24.

It should also be noted that many light airplanes are equipped with integrated navigation systems that do not include inertial sensors. In such cases, dead-reckoning techniques are employed to estimate the airplane’s position based on airspeed and heading measurements. However, this method provides reliable results only over short time intervals and is considerably less accurate than inertial navigation [13]. The high cost of inertial navigation equipment limits its use in rotorcraft and general aviation, resulting in a large segment of aircraft that possess only a short period of dependable navigation capability in the absence of GNSS signals.

During extended interruptions of the primary positioning source, conventional navigation using ground-based radio beacons, such as DME, VOR, and NDB must be initiated [14]. On-board flight management systems utilize data from these ground-based aids either to maintain the desired flight path or to compute the airplane’s position [15]. Within the framework of Performance-Based Navigation (PBN) [3], positioning derived from ground-based radio navigation aids (GRNA) is recognized as the principal backup technology supporting civil aviation operations in GNSS-denied environments.

Nevertheless, the accuracy of GRNA derived positioning is significantly lower than that achieved with GNSS level and is highly dependent on the density and configuration of the supporting ground infrastructure. Moreover, each GRNA installation has a limited service volume determined by the range of its radio communication line [16,17]. Therefore, a sufficiently dense and well-distributed network of GRNA is required to ensure continuous navigation capability within a given airspace region.

Common equipment of modern airplanes could operate only with a pair of GRNA, therefore only three algorithms could be used on-board to identify position by a network of GRNA: DME/DME, VOR/DME, and VOR/VOR [3]. Previous studies highlight that only DME/DME positioning could fully support the required precision level of basic area navigation (RNAV 1) specification, which is mandatory for the en-route phase of flight [18]. Navigation with VOR/DME is limited by range and could be effective only in areas close to GRNA. That makes VOR/DME suitable for departure and arrival phases of the flight. Algorithms of VOR/VOR and NDB/NDB positioning could not provide the minimum required level of precision, making ground networks of VOR and NDB suitable to provide only basic navigation capability in case of an emergency situation.

Modern aviation infrastructure roadmaps worldwide emphasize the continuing importance of GRNA networks for civil aviation [19,20]. These strategic plans typically prioritize the expansion and modernization of the DME network to increase coverage and enhance performance, with the objective of ensuring compliance with RNAV 1 specifications throughout the airspace to provide infrastructure sustainability. In parallel, the number of VOR facilities is being progressively reduced to maintain only the minimum operational capability required for safety assurance. Conversely, NDBs are widely regarded as obsolete and are scheduled for decommissioning in future navigation infrastructure plans.

The development and maintenance of GRNA networks fall under the responsibility of Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs), which ensure the safety and resource efficiency of air traffic management within its jurisdictions. Each ANSP deploys and operates its ground-based navigation aids in accordance with national or regional smart infrastructure development roadmaps. However, the high cost of establishing and maintaining GRNA systems results in significant disparities between regions. ANSPs in economically constrained states often operate only limited networks that support basic navigation functions and provide minimal RNAV 1 capability. In contrast, ANSPs in developed countries with high air traffic density are able to sustain well-developed and redundant GRNA networks. This global imbalance in infrastructure performance introduces additional safety risks, as regions with sparse GRNA coverage lack a reliable backup positioning service in the emergency case of a wide GNSS service lock.

The primary contribution of this article is to provide a comprehensive scientific assessment of the joint global GRNA network, focusing on its structural properties and the performance of the navigation services it provides to civil aviation. Obtained results help to understand the current level of area navigation specifications implementation in different ICAO regions globally. The on-board flight management system of modern airplanes contains global databases of GRNA stations and utilizes all available beacons collaboratively for position determination. Therefore, ensuring aviation safety from the perspective of the airspace user requires a holistic understanding of the integrated global network’s performance, rather than isolated analyses of local or regional systems. To address this need, the article investigates combined DME and VOR ground networks on a global scale, applying an airspace partitioning approach to evaluate their collective capacity to support area navigation requirements.

Also, the article proposes a novel approach that leverages the performance of GRNA network based on airspace partitioning with a geospatial indexing system. Developed algorithm of airspace geospatial analysis evaluates spatial distribution of studied network parameters based on a specified level of precision.

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of relevant literature and previous research on radio navigation networks and RNAV implementation. Section 3 describes the proposed methodology for network performance evaluation and introduces the novel algorithm developed for spatial airspace analysis. Section 4 presents and discusses the results of the global radio navigation network estimation, provided to support the implementation of RNAV specifications. Finally, Section 5 and Section 6 summarize the main findings.

2. Literature Review

The DME is an active two-way ranging system widely used in civil aviation to determine the distance between an airplane and a ground station. A common error model of range measuring includes two primary components: errors introduced during signal propagation through the atmosphere and systematic and random errors originating from the on-board interrogator equipment. According to normative documents [3], DME must provide a positioning accuracy of no less than 1.1 km.

However, results from recent performance evaluations of modern DME systems operated by ANSP demonstrate that DME are capable of achieving significantly higher precision, with a total error budget of less than 0.05 NM (approximately 62 m). Such performance levels indicate the strong potential of DME to support the evolution of GRNA to meet the requirements of future positioning and navigation technologies [21,22]. Furthermore, several research groups have been actively engaged in developing new DME signal structures aimed at substantially improving positioning accuracy and robustness [23,24].

There are several positioning algorithms that could be used to identify the position of an airplane by data from DME network. Performance of positioning by DME/DME is studied for the case of navigation by a pair of GRNA [25,26]. A regression model with non-linear Spline functions is proposed to accumulate measurements of pair equipment to apply a multi-DME positioning approach [27]. Performance of multi-DME positioning approach is studied in [28,29,30,31] based on the least-square method. Also, improvement of DME/DME positioning performance could be reached by minimization of the multipath effect [32,33].

An improved algorithm of positioning by multiple VORs with paired measurements and accumulated data is proposed in [34]. Obtained results indicate low precision of navigation by only one pair of VOR/VOR, which is significantly poorer than the required level in RNAV 1. An improved algorithm could increase the precision of a multi-VORs approach, but due to poor ground network geometry, RNAV 1 requirements could not be reached. A specific fusion approach of VOR/DME and GNSS is proposed in [35] to improve position performance in case of GNSS service outdates.

Performance of the GRNA network to support positioning by pairs of DME/DME (which is currently used in civil aviation) is studied for the local subnetwork of USA [36]. Network optimization, with the help of genetic algorithms proposed in [37], helps to minimize network order and improve positioning performance. This approach has been validated with data from Italian DME network geometry.

Network performance evaluation has been investigated in [38] for the scenario of precise DME, which employs stretched-front-leg pulse in airspaces of Florida and South Korea. Estimation of network performance using a combination of a rule-based model and gradient boosting regression is studied in [39] for the European airspace as well.

The algorithm for partitioning airspace into a set of elementary cells for evaluating DME/DME navigation performance was proposed in earlier studies [40,41]. The obtained results emphasize the importance of network performance assessment to ensure the safety of civil air transportation, as such evaluations help identify regions where the requirements of RNAV 1 cannot be fully guaranteed.

The review of existing literature underscores the crucial role of radio navigation aids in the ongoing development of an intelligent transportation system and in enhancing the safety and reliability of civil aviation operations. A key challenge facing the global aviation community lies in the optimization and consolidation of navigation networks to enable efficient service provision under the conditions of multi-network positioning capability.

Furthermore, the literature review reveals a notable research gap in the analysis of angle-based GRNA. Existing studies have primarily focused on DME/DME networks, while VOR/VOR and VOR/DME network configurations have received little attention in scholarly studies.

It should be noted that all present approaches to GRNA network analysis consider only rectangular geometry of the elementary cell for network performance evaluation, which has several disadvantages, including data distortion for visualization in different cartographical projections, a non-regular shape, and being computationally heavy, which limit analysis in the domain of local networks.

3. Methodology

Analysis of GRNA network performance on a global scale should begin with the formation of integrated networks, developed separately for each type of navigation equipment. The topological characteristics of each network must then be evaluated to determine the effective service volumes that support aircraft navigation and positioning. Within the service area of each combined GRNA network, the positioning performance achievable by pairs of navigation aids should be quantitatively evaluated. The derived performance parameters serve as a basis for collaborative decision-making regarding the compliance of the network with RNAV operational requirements. Finally, the results of this analysis can be aggregated to evaluate spatial distribution of the key informative parameters across the global airspace volume.

3.1. Network Topology

In this study, we focused on properties of the global services of DME and VOR. Thus, it makes sense to consider these networks separately.

DME is an active ranging system. On-board equipment of DME transmits an interrogation signal which includes two pulse-pairs. The ground beacon receives this signal and, after a fixed time of delay, transmits a copy of the signal as a reply. On-board equipment receives a reply and measures the time of the signal round trip, which is proportional to the direct distance between the airplane and GRNA.

Each ground station of VOR transmits a navigation signal in which two sub-signals are included: a reference signal (frequency modulated) and a signal of variable phase (amplitude modulated). The on-board receiver of VOR calculates the phase difference between these sub-signals, which is proportional to radial angle. This angle is a magnetic bearing from the VOR beacon to the airplane.

Co-located VOR/DME is a universal navigation tool, which identifies the position of an airplane based on measured radial angle and range (polar coordinate system). Thus, it is highly used in the airport vicinity to navigate airplanes in standard schemes of departure and arrival. For the en-route phase of flight, a separate configuration of beacons is used. Initially, networks of GRNA have been tuned to provide stable navigation within a flight route network. In this case, GRNA are commonly placed in waypoints. Since 2008, local networks of DME and VOR have begun a global initiative of ICAO in reconfiguration to meet the requirements of RNAV. This includes changing the node’s location to achieve the required positioning performance. Many ANSPs around the world successfully completed the reconfiguration stage, but many of them are still in the deployment stage.

Global networks of GRNA could be represented as an undirected graph, properties of which could be studied based on classical graph theory. Two graphs could be useful in this analysis: the complete graph and the graph of pairs. Both graphs use the same nodes associated with a beacon. In a complete graph, every node is connected to all other nodes. For a complete graph, each node has a constant degree () and the number of edges is as follows:

where

is number of nodes.

In a graph of pairs, an edge is created only between nodes that form a pair for position measuring by DME/DME and VOR/VOR algorithms. In the common case graph of pairs is a planar graph for which no two edges cross each other due to each node being connected only to closed (neighbor) nodes.

Both graphs are specified by an adjacent matrix A and weighted by the direct distance between beacons (). An adjacent matrix is a square binary matrix that specifies a pair of connected nodes:

where

is a binary element which specifies the presence of an edge to connect i-th and j-th nodes and

is the direct distance between i-th and j-th beacons.

Matrixes

and

are symmetric:

and

. Graphs of global networks of beacons could be specified as follows:

A graph

is used to calculate node degree, which indicates the number of connections a beacon has to other ground stations in the graph:

Also, weighted node degree is a useful metric:

A beacon with a high degree in a graph of pairs could be considered as overloaded due to participation in multiple pair formation processes. Beacons with low degrees could be located in the periphery of the graph, which highlights the coastline navigation facility. Some beacons could be classified as isolated (), which marks this facility as useless for positioning methods and indicates poor navigation infrastructure according to PBN.

An area allocated to each beacon in a Voronoi diagram is another important parameter that indicates density of the network. A Voronoi diagram provides a region for every beacon, for each point at which this beacon is closer than any other in the network. An area of this region could be calculated as follows, based on the calculated ordered vertices of the Voronoi cell

:

All three parameters, degree, weighted degree, and area of cell in Voronoi diagram, should be used in collaborative decision-making to identify poor network configuration.

3.2. Availability of GRNA Network

Services of GRNA are provided for users (airplanes) that are located within the service area (volume). Beacons use direct radio communication with an airplane to send navigation signals. VOR uses Very High Frequency band in the range 108–117.95 MHz [2]. DME uses Ultra High Frequency in the range 960 MHz–1.215 GHz.

The maximum length of a wireless datalink could be estimated based on the radio-link budget and free-space loss model:

where

is ground beacon transmitter power [dBW];

is the on-board receiver sensitivity [dBW];

and

are the gain function of the beacon transmitter and on-board receiver [dBi]; and

is a carried frequency used in communication radio-link [MHz].

The gain function of on-board equipment has omnidirectional properties, which are limited by the airplane body. However, the gain of the ground beacon has a more complicated shape:

- –

- Gain has constant values for different azimuthal angles in the horizontal plane;

- –

- In the vertical plane the gain function has main and side lobes.

In addition, the maximum range in Equation (7) has been influenced by ground, radio wave diffraction from hills and mountains, and multipaths from nature and artificial construction that significantly reduce the service area of beacon. To minimize the influence of relief, an antenna pattern in the vertical plane of the ground beacon has a specific shape to minimize reflection from the ground. The troposphere also influences the radio wave propagation model, which affects distance measuring in DME. All these effects made the service volume of DME have a complicated model, which is unique for each ground beacon.

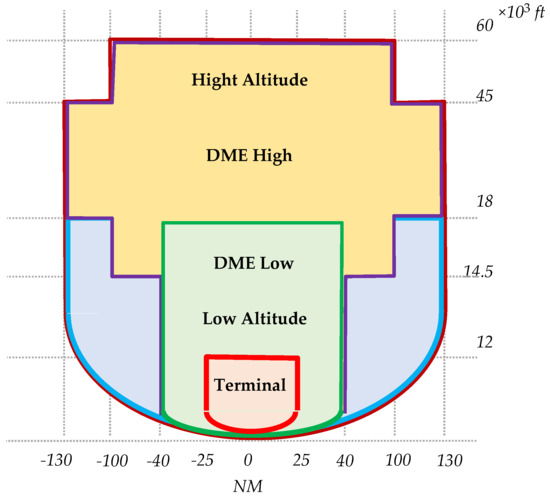

For practical application in airplane navigation, ANSP uses a simplified model of beacon service volume. This model structure uses several cylindrical elements with specified height and radius. Airspace users (airplanes) at any point located within this 3D model could have access to all services provided by the ground navigation beacon. This volume of airspace is called standard service volume of beacon (SSVB). Technical parameters of SSVB for each GRNA are specified by each ANSP in an aeronautical information publication (AIP). Airlines, pilots, or any other airspace users take into account the geometry of each SSVB across the flight trajectory to plan which navigation equipment could be used. The flight management computer system (FMCS) includes a database of global radio navigation aids to serve navigation while en-route. The algorithm of FMCS uses a type of GRNA available in the internal database to obtain SSVB and identify an effective pair of equipment to provide the most fruitful pair for positioning. Each ANSP could use its own model structure, but the most commonly used classification includes three basic types [42]:

- –

- Terminal. In the altitude range from 1 × 103 ft up to 12 × 103 ft; operational radius is 25 NM.

- –

- Low Altitude. In the altitude range from 1 × 103 ft up to 18 × 103 ft; operational radius is 40 NM.

- –

- High Altitude. Has a combination of three cylinders:

- •

- Radius is 40 NM for altitudes from 1 × 103 ft up to 14.5 × 103 ft;

- •

- Radius is 100 NM for altitudes from 14.5 × 103 ft up to 60 × 103 ft;

- •

- Radius is 130 NM for altitudes from 18 × 103 ft up to 45 × 103 ft.

In addition, according to [43] there are two extensions of SSVB:

- –

- DME Low. Radius is 130 NM for altitudes from 12.9 × 103 ft up to 18 × 103 ft.

- –

- DME High. Radius is 130 NM for altitudes from 12.9 × 103 ft up to 45 × 103 ft and 100 NM radius for the altitudes from 45 × 103 ft up to 60 × 103 ft.

A geometry comparison for beacons of different types is given in Figure 2, showing SSVB grounds on cylindrical models with an exponential approximation in the lower part.

Figure 2.

Comparison of SSVB of different types.

The real service volume of a beacon is much wider than SSVB, but may include some gaps. Services out of these cylindrical models could be available, but not granted by ANSP.

Availability estimation requires identification of areas in which a particular number of GRNA are available. There is no analytical solution to identify the geometry of contour lines for the availability areas of GRNA. Therefore, only the brute-force method could be used. In this case, airspace is represented as a set of elements. Availability within a cell is considered constant. Coordinates of the cell center are used to probe the number of GRNA that could be available.

Based on the required precision level, considered airspace is partitioned into a set of cells as follows:

where

is a unique cell index and

is amount of cells used at a particular level of precision within a defined region.

In most cases, network performance is estimated for a particular altitude. A cell represents a fragment on the surface of an ellipsoid. A basic WGS-84 ellipsoid is used, which is enlarged to reach the considered altitude at which network performance is evaluated [44,45].

Availability is analyzed by a simple check if the distance between the GRNA and airplane is lower than the maximum range wireless datalink estimated by Equation (7):

where

is the coordinate of GRNA in ECEF reference frame and

is the coordinate of a particular cell center in ECEF.

Also, the availability area could be estimated based on SSVB. In this case, for a particular altitude, based on the given GRNA model, the active radius of the cylinder is identified. Radius specifies a maximum range in which service could be provided. Thus, horizontal distance between airplane and GRNA should be compared with radius of cylinder, which gives the following trigger:

where

is the radius of cylinder valid for given altitude;

is the mean Earth radius ( km);

is the altitude above WGS84 surface for which analysis is provided;

,

are the coordinates of a particular cell center in geocentric latitude and longitude; and

,

are the coordinates of GRNA.

Based on trigger (9) or (10), obtained “True” indicates that the service of a particular GRNA is available in a particular cell. Results of the availability analysis give a matrix of cell indexes and identification codes of GRNA, which are available for measuring navigation parameters.

Positioning by pairs of radio navigation aids (only for DME/DME and VOR/VOR) is possible only in the case where at least two beacons are available for parameter measuring. Thus, for each cell of airspace, the number of available GRNA is used to form pairs. Pairs for which the internal angle meets requirements from 30° to 150° could be used in further considerations [3]. Formed pairs are used in performance evaluation, and the most accurate pair could provide an efficient positioning process. The number of available pairs is an important parameter for the reliability analysis of positioning by radio navigation aids.

A larger number of available pairs means more options are given in case of fault in navigation environment. Thus, it affects reliability of provided services, which could be represented in terms of the probability of a failure-free operation (PFFO). PFFO is the probability of failure in navigation equipment, which will not occur within a given duration. PFFO is estimated as follows:

where

is duration of navigation equipment usage;

is mean time between failures for one radio navigation aid; and

is number of pairs available at a particular cell.

Probability of failure (POF) is another important performance indicator, which is opposite to PFFO. POF is the probability of condition at which at least one failure occurs within a given duration:

Both POF and PFFO are used to quantify reliability of positioning equipment.

3.3. Accuracy of Positioning by Pairs of GRNAs

The accuracy of maintaining a predefined airplane trajectory is a key element of safety in air transportation. Accuracy is specified by Total System Error (TSE). A basic model of TSE consists of only two components: Flight Technical Error (FTE) and Navigation System Error (NSE) [3]:

Both error components are described by a Gaussian statistical model, which is represented with the help of standard deviation (σ). Standard deviation quantifies the statistical scatter of position errors around true position. According to PBN, these errors are specified with 95% of confidence probability level, which corresponds to ±2σ interval.

FTE utilizes the error of piloting mode, which could cause an airplane to deviate from the cleared trajectory. FTE depends on piloting mode. For manual flight control, by pilot, FTE could reach 0.3 NM. However, for autopilot mode, FTE could reach significantly lower levels (FTE = 0.25 NM). In this study, only en-route phase of flight is considered; therefore, due to most civil traffic using autopilot mode, it makes sense to use FTE = 0.25 NM for evaluation of the TSE value.

NSE represents the error of the sensor that measures position. NSE depends on the positioning algorithm used in FMCS. There are three commonly used positioning algorithms by pairs of GRNA in civil aviation: DME/DME, VOR/DME, and VOR/VOR. The last VOR/VOR is rarely used due to poor performance; however, accuracy of this method is still an important characteristic of VOR ground network infrastructure.

Position detection by a pair of DME/DME grounds by simultaneously measuring two ranges from the airplane to the pair of DMEs. This operation is initiated by FMCS in a fully automatic mode and realized via an on-board radio-management panel and two on-board interrogators. Then, FMCS uses measured two ranges and coordinates of ground DMEs (from air navigation database) to calculate the position of the airplane by the time of arrival method. A Global Earth-Centered, Earth-Fixed reference frame or Local North-East-Up Cartesian coordinate system with a reference point associated with a particular DME in the pair of DME/DME could be used for the navigation equation. The navigation equation for a pair of DME/DME is a quadratic equation, which gives analytical formulas to calculate airplane position. As a result, it provides two positions, one of which is false. Correct coordinates are identified by the closest location to the previously available airplane position.

Accuracy of positioning by a pair of DME/DME is represented by standard deviation (), which is used in NSE based on 95% confidence probability [3]:

where

is a standard deviation error introduced by a signal traveling in space and the ground DME facility (means outside of interrogator);

is the standard deviation error introduced by the on-board DME interrogator (mostly by time-traveling measuring equipment); and

is the inclusion angle between directions to ground stations.

Standard deviation of a signal traveling in space and the ground DME facility () in the common case is considered to be below 92.6 m (0.05 NM).

Standard deviation error introduced by on-board DME interrogator is represented by a linear relation from the DME range [3]:

where

is measured range from the airplane to DME ground beacon, [m].

Positioning by VOR/DME is grounded by a simple navigation equation in a local Cartesian reference frame:

where

is the angle measured by VOR; VAR is the angle of magnetic variation in a particular VOR; and

is the measured range to ground DME.

VOR provides angle measuring in relation to magnetic North, therefore it requires use of magnetic variation data of a particular VOR () available in AIP.

Accuracy of positioning by pair of collocated VOR/DME could be estimated based on a Taylor series expansion limited by first order of derivatives:

where

is the standard deviation error of range measuring in DME [m];

is the range measured to ground DME, [km]; and

is a standard deviation error of angle measuring in VOR, [rad].

Normative documents [2] warn of standard deviation error from angle measuring in VOR by 1°, thus:

Positioning by pair VOR/VOR grounds uses the angle of arrival method, which is based on trigonometric functions. The navigation equation for VOR/VOR in an NEU reference frame with reference point co-located with one of VORs is as follows:

where

,

are the coordinates of VOR 2 in NEU with reverence point at VOR 1 and

is the angle measured from VOR.

Accuracy of the positioning by pair of VOR/VOR method could be estimated as follows:

Estimated value of NSE is used with FTE to calculate TSE by (11) for each method of positioning.

Ensuring the safety of civil aviation is based on the accuracy of each airspace user following a preplanned trajectory. The level of acceptable deviation is specified in the area navigation specifications of PBN. There are four basic RNAV specifications used today: RNAV 1, RNAV 2, RNAV 5, and RNAV 10. Mainly, RNAV specifies requirements for the accuracy of lateral navigation with 95% probability of confidence. Application of each RNAV specification and required TSE is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

RNAV levels.

Table 1 includes levels of FTE that should be used for navigation procedure design and infrastructure evaluation [3].

The estimated value of NSE for each available positioning method is used with the corresponding value of FTE to obtain the TSE. The evaluated TSE value should be compared with the required levels of TSE for each specification. The RNAV trigger helps to identify the validity of the available radio navigation aids infrastructure to meet area navigation requirements.

3.4. Algorithm of Global Airspace Analysis

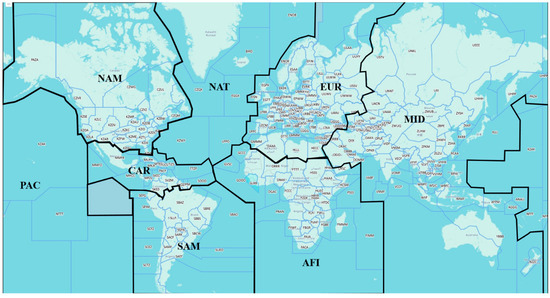

Performance evaluation of the radio navigation aids network requires a reliable method of airspace representation and analysis. ICAO developed a global structure of airspace which includes eight regions [46]:

- –

- Africa-Indian Ocean region (AFI);

- –

- Caribbean region (CAR);

- –

- European region (EUR);

- –

- Middle East region (MID);

- –

- North American region (NAM);

- –

- North Atlantic region (NAT);

- –

- Pacific region (PAC);

- –

- South American region (SAM).

Each region coordinates the planning and implementation of air navigation services among its member states. ICAO introduces the division of each airspace region into Flight Information Regions (FIRs) or Upper Information Regions (UIR) to ensure the safety and efficiency of air travel. This structure of airspace division is a critical aspect of air traffic management, creating clearly defined areas of responsibility for air navigation services. FIR is a lower airspace, which starts from the surface up to the lower limit of a UIR. UIR is an upper airspace, which starts from its lower limit (mostly FL245) upwards. Lateral limits of FIR are unique for each airspace. Boundaries are specified based on international agreements between countries.

Therefore, it makes sense to use the region metric of ICAO to validate the performance evaluation of navigation aids over the globe.

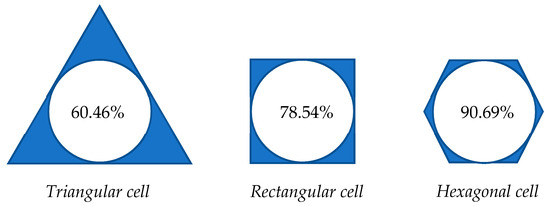

Evaluation of network performance requires representation of airspace as an asset of elementary cells. The distribution of performance parameters within the cell is considered constant. There are three basic cell types that could be used for global airspace partitioning: triangular, rectangular, and hexagonal [47,48].

An ellipsoidal shape could be partitioned based on a particular level of precision into a set of cells. The triangular cell has a great following of the ellipsoidal model. However, data representation introduces wrong values at the triangle vertex. Thus, values at the center and vertices could not be considered constant. Therefore, this shape could not be efficient for data analysis.

A rectangular cell is commonly used for airspace analysis due to significantly easier practical implementation, which involves simple division of latitude and longitude ranges into equal regions. But latitude and longitude are angles that make the cell of rectangular geometry differently shaped between the equator and polar regions. This property does not fit well into global airspace analysis.

The hexagonal shape of the cell fits best with the airspace representation. An important property that highlights the usage of a hexagonal cell is if the correspondence of the cell area fits the inscribed circle. Errors of positioning are described by circular error, therefore the minimum of the inscribed circle area is a logical criterion for effective cell geometry choosing. Figure 3 illustrates the level of cell area fit of the inscribed circle. The inscribed circle for an equilateral triangle covers 60.46% of the total area, 78.54% for a square, and 90.69% for a regular hexagon. Thus, the hexagonal cell meets the best circular data representation.

Figure 3.

Comparison of cell shapes.

There are several geospatial indexing systems that could be used for the task of airspace partitioning. Global indexing systems provide not only a partitioning mechanism but also a unique addressing of each cell element in the system. Most systems use hierarchical indexing, which means that each cell of a particular level of precision includes several cells at a lower level of precision. Also the index of a bigger cell could be recovered from each lower cell index, which makes indexing highly useful in geospatial data analysis. Open Location codes (OLC) are the most commonly used system with a rectangular cell [49]. OLC uses 162 cells at the initial precision level. Each of these cells forms a cell grid of 400 sub-cells at the lowest precision level. There are five basic levels of precision that provide ellipsoidal shape coding with precision up to 13.9 m. One of the disadvantages in the system is a big step size for jumping between different precision levels.

The hierarchical hexagonal index system (H3) uses a hexagonal grid shape with regular hexagons placed at 16 different resolution levels [50]. H3 uses an icosahedron (a 20-sided shape) as its base. Ellipsoidal data is mapped onto this shape, and the hexagonal grid is built on its faces. Due to it being impossible to tile a sphere perfectly with only hexagons, 12 pentagons are placed at the vertices of the icosahedron to complete the grid. H3 includes 122 cells at the initial resolution level. The highest level of precision in H3 operates with hexagons of area within 0.895 m2. This corresponds with the average edge length in 0.58 m [51].

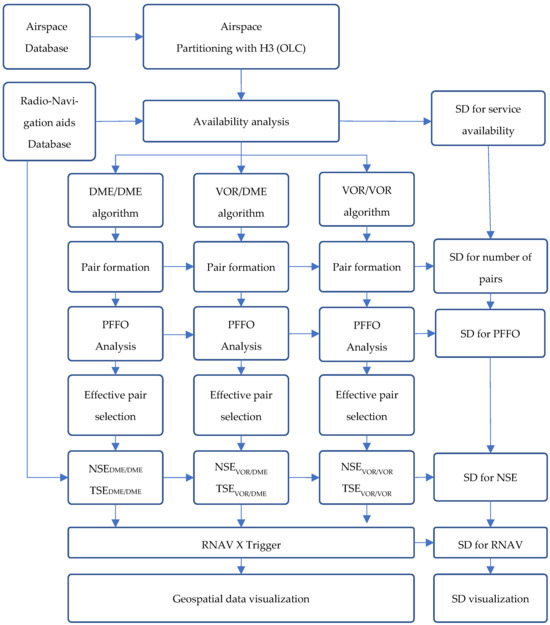

A special algorithm has been developed to realize global airspace analysis of services provided by the radio navigation aids network. The structure scheme of the propped algorithm is given in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Algorithm of airspace geospatial analysis.

An airspace database is used to obtain the shape of each of the nine ICAO regions. The space inside this shape geometry is partitioned into a set of elementary cells (H3 or OLC). The geometrical center of each cell is used to estimate the availability of beacon services by trigger (10). An estimated array of available GRNA is used in the pair formation process by the type of navigation method and to estimate spatial distribution (SD), which shows the area of airspace at which a particular number of beacons is available. SD helps to analyze particular parameter distribution over a geo-area. SD is a rich metric for providing an airspace description of a particular parameter quality. Based on the number of available GRNA, a PFFO is estimated. NSE and TSE are evaluated for each positioning method. Estimated values of TSE are triggered to meet the requirements of a particular RNAV. Finally, all data are visualized.

The proposed algorithm has been used in software design in JavaScript (ES2020) with data visualization in OpenStreetMap (API v 0.6) based on the Open Layers (v9.2.4) and d3 (v7.9) library for SD data analysis.

4. Results

In this study, we use the ICAO region as the main structural element of airspace to evaluate performance of the global network of GRNA. Eight regions are covered: Africa-Indian Ocean (AFI), Caribbean (CAR), European (EUR), Middle East (MID), Pacific (PAC), North Atlantic (NAT), North American (NAM), and South American (SAM). The geometry of each region used in the computer simulation is given in Figure 5. Each region includes a particular number of FIRs. Overall characteristics of ICAO regions are given in Table 2. Table 2 includes the number of FIRs that form the geometry of each region, the average area of the region accounted for the level of WGS84 ellipsoidal surface with respect to total airspace, as well as the amount of hexagonal cell used for partitioning this airspace at the 6th level of precision in H3, which use a hexagonal cell with average area of 36 km2 and average side length of 3.7 km.

Figure 5.

Geometry of ICAO regions.

Table 2.

Geometrical properties of each region.

4.1. Availability of GRNA Services

In this study, a database of global GRNA is used. The validity date of the database is October 2025. The radio navigation aids database includes 4639 records, distributed as follows: 3676 (DME and TACAN), 2783 (VOR), 834 (NDB), and 2675 (co-located VOR/DME and VORTAC). The database includes the type of GRNA and SSVB model characteristics. In the simulation, GRNA, which could provide services for en-route airplanes, is considered only. Therefore, an altitude of 4550 m, which corresponds to FL150, is used. FL 150 has been chosen to involve most types of GRNA, excluding terminal ones. Terminal beacons are used for navigation during departure and arrival phases and are not available en-route. Results of GRNA availability estimation are given in Table 3 in the number of available equipment, services of which are available within the region. Amount of available GRNA includes ground facilities placed in FIRs which are inside a particular region, but also includes radio navigation aids located in neighboring FIRs, services of which are available in the analyzed ICAO region. Therefore, the total amount of GRNA in Table 3 is bigger than the database size.

Table 3.

Number of available GRNA.

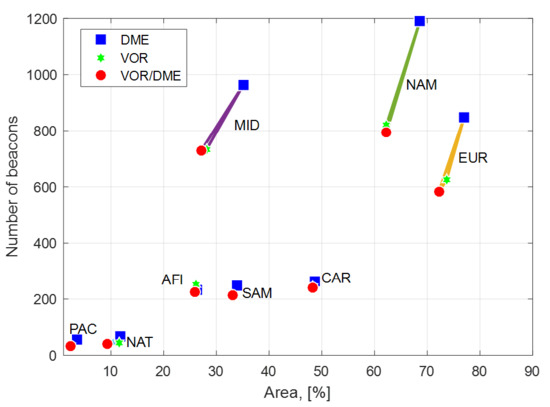

Table 4 gives the results of the service area availability analysis within the area of region for each type of GRNA. Data in Table 4 includes results of area calculation as the sum of elementary cell areas in which at least one beacon is available. Also, it includes a portion of the area compared to the whole area of the considered region, which makes it possible to analyze how regions are equipped with a particular type of radio navigation aid. Comparison of service area development across different regions is given in Figure 6.

Table 4.

Service area of each GRNA type within each region.

Figure 6.

Comparison of service area development in each region.

Parameters of the number of beacons and portion of area where services are provided point out that EUR and NAM regions are the best-equipped regions for all three positioning methods. Also, DME service area in the EUR region gives the widest service area at 76.99%, which mostly covers the continental side. The NAM region reaches 68.63% of coverage area only. Both regions have a significant non-covered area in the pre-polar part of the region. The MID region includes many beacons; however, wide area of the region results in only 35.14% of DME service area. At the same time, a wide ocean area with no possibility to use ground beacons makes PAC and NAT regions have poor service area (3.53% and 11.78% of service area, respectively).

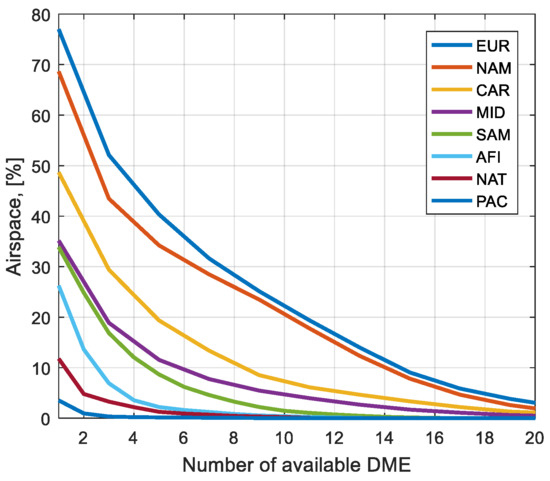

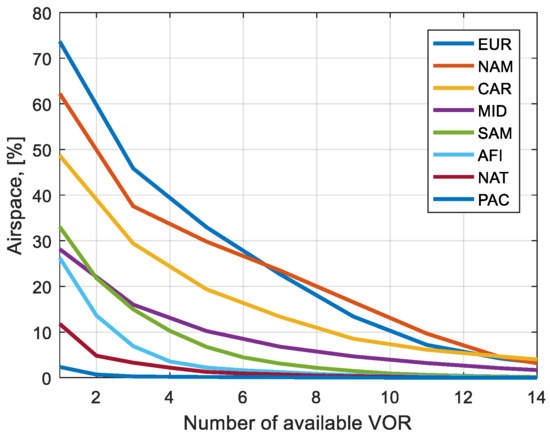

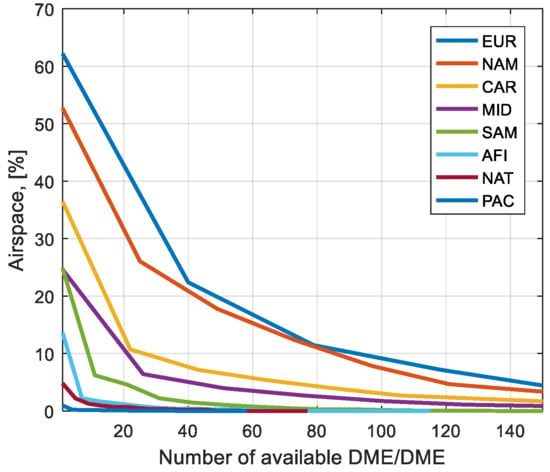

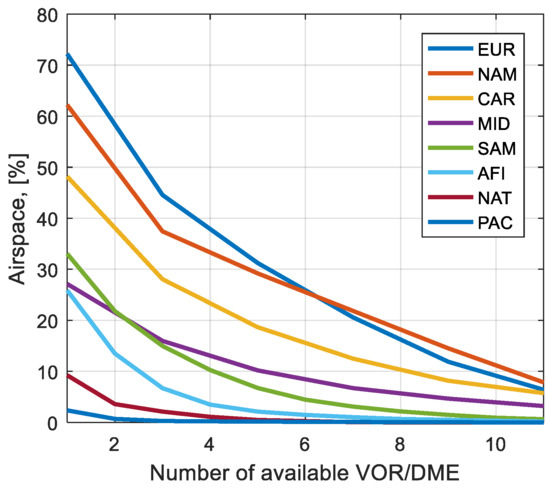

The quality of service area provided by DME and VOR networks could be analyzed with the help of spatial distribution functions. Results of SD estimation for service availability are given in Figure 7 for the DME network and Figure 8 for the VOR network.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of number of available DME.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of number of available VOR.

Results in Figure 7 and Figure 8 show a portion of airspace and the number of ground beacon services that could be available for navigation. The SD of DME availability shows that the EUR region is the best equipped in the world. The SD of VOR highlights that the EUR region is the best equipped for the services of seven ground stations; however, NAV is the best for levels above seven. Both SDs show that the services of DME and VOR are available in more than 60% of airspaces.

4.2. Availability of DME/DME Services

Position determination using DME/DME pairs is one of the key capabilities of the navigation network that ensures the safety and reliability of air transportation. The number of available DMEs within each airspace cell is used to form potential DME/DME pairs for navigation. Due to the geometric configuration of the ground stations, each pair provides a different level of positioning accuracy. However, the total number of available pairs indicates the potential redundancy and robustness of the positioning system. Some distance measurements with a specific DME may fail if the interrogation signal reaches the ground receiver during its “dead time”. Therefore, the availability of multiple DME/DME pairs contributes to a higher level of reliability in position determination.

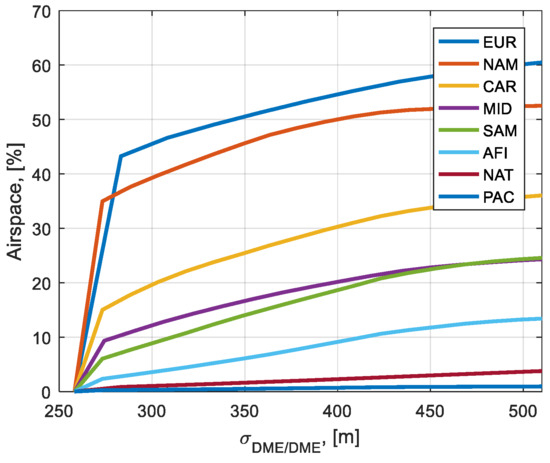

The estimated distribution of available DME/DME pairs across the analyzed airspace is presented in Figure 9. The analysis includes only those pairs that satisfy the geometric constraint on the internal angle between 30° and 150°. The positioning accuracy for each pair was estimated using (14). The spatial distribution of the achievable accuracy for the most accurate DME/DME pair (the pair providing the highest positioning accuracy) is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Spatial distribution of available number of DME/DME pairs.

Figure 10.

Spatial distribution of the achievable accuracy

.

Figure 10 illustrates the capability of the DME network to provide different levels of positioning accuracy. The TSE is compared with the requirements of area navigation to determine the proportion of airspace that meets the navigation accuracy criteria. The results of the RNAV 1 availability analysis are presented in Table 5, which summarizes the estimated area compliant with RNAV 1 standards and its corresponding share within each analyzed airspace region.

Table 5.

Area of DME/DME navigation compatible with RNAV 1.

The EUR region demonstrates a dominant share of airspace with valid RNAV 1 navigation capability based on DME/DME positioning. However, the MID region covers the largest total airspace area, with 34.98 million km2, compared to 17.72 million km2 of RNAV 1 compliant airspace in the EUR region. The lowest level of DME/DME-based positioning service is observed in the PAC region, where the RNAV 1 compliant area is only 1.07 million km2, representing merely 0.95% of its total airspace.

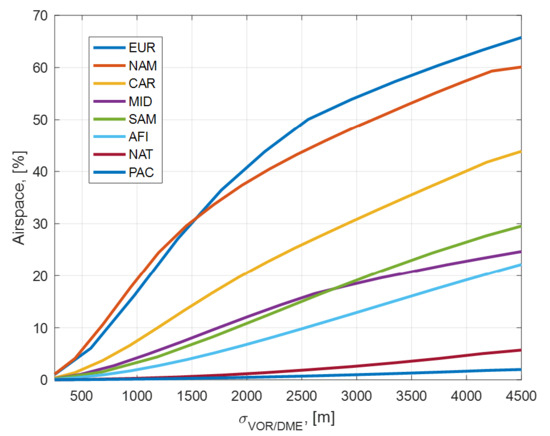

4.3. Availability of VOR/DME Services

Co-located VOR/DME ground facilities are commonly used for aircraft navigation in airport vicinities. However, the service range of these systems also enables their use for navigation during the en-route phase of flight. The spatial distribution of available VOR/DME services for navigation is presented in Figure 11. Coverage analysis shows that the services of at least two co-located VOR/DME stations are available in more than 50% of the airspace in the EUR and NAM regions. The results of the standard deviation error estimation by Equation (17) for VOR/DME positioning are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 11.

Spatial distribution of number of available co-located VOR/DME.

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution of

.

The obtained results indicate that the NAM region provides the most favorable spatial distribution of VOR/DME coverage for aircraft operating near ground facilities. In contrast, the EUR region demonstrates the largest area covered at longer ranges, reflecting its well-developed navigation infrastructure. The PAC and NAT regions exhibit the lowest performance levels, primarily due to the limited number and large separation of ground-based navigation stations.

The positioning accuracy provided by VOR/DME pair directly depends on the distance between the aircraft and the ground facility. As the distance increases, the accuracy significantly degrades, which explains the applicability of different RNAV specifications, ranging from RNAV 1 to RNAV 10. The results of the airspace availability analysis, indicating compliance with the corresponding RNAV requirements, are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Area of VOR/DME navigation compatible with RNAV specifications.

The analysis of airspace compliance with RNAV 1 requirements shows that only 16.52% of the NAM region meets the specified accuracy level, despite being the best-equipped area. In contrast, RNAV 5 requirements are satisfied within 66.6% of the EUR region and 60.48% of the NAM region. Compared with DME/DME navigation, the available airspace area supporting RNAV 1 using VOR/DME positioning is considerably smaller. Consequently, the VOR/DME method demonstrates a lower operational priority in the navigation system collaborative decision-making process.

4.4. Availability of VOR/VOR Services

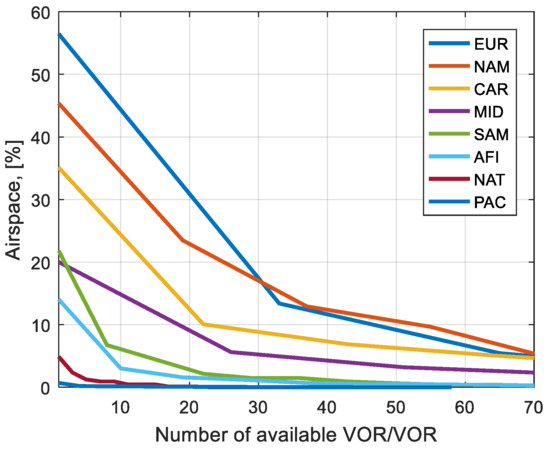

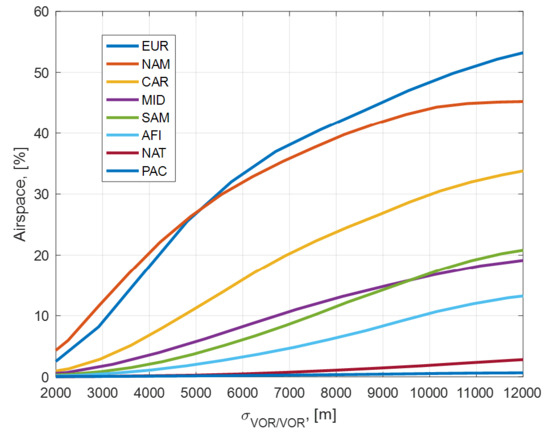

Positioning based on a pair of VOR/VOR ground beacons relies on the angle of arrival method, which is far from optimal for supporting modern civil aviation requirements. The performance of angle measurement in VOR systems is relatively poor; both regulatory standards and experimental tests indicate that the standard deviation of bearing error is typically limited to about 1°, resulting in low positioning accuracy. Furthermore, many ANSPs have reduced their operational VOR infrastructure to a minimum configuration in order to optimize costs and improve the efficiency of air navigation services. Consequently, existing VOR subnetworks are often not geometrically configured to ensure effective positioning using VOR/VOR pairs. The results of analysis in available VOR/VOR pairs are presented in Figure 13, which was created based on combinations of two datasets shown in Figure 7 and by considering pairs with intersection angles between 30° and 150° only, representing the operational region where positioning accuracy remains acceptable.

Figure 13.

Spatial distribution of available VOR/VOR pairs.

The results indicate that only within the EUR region does more than half of the whole airspace have access to over five VOR/VOR pairs. The positioning performance analysis, calculated using Equation (21), is presented in Figure 14. Overall, the VOR/VOR analysis demonstrates that although the EUR region has the highest pair availability, the NAM region exhibits the most favorable network geometry, achieving the highest positioning performance within approximately 25% of its airspace. The TSE results for VOR/VOR positioning and their compliance with RNAV requirements are summarized in Table 7.

Figure 14.

Spatial distribution of the achievable accuracy

.

Table 7.

Compatibility of VOR/VOR positioning coverage with RNAV requirements.

The results of RNAV availability analysis demonstrate that RNAV 1 performance requirements can be satisfied through the use of VOR/VOR positioning; however, this capability is limited to a relatively small portion of the airspace. The most extensive RNAV 1 compatible area is observed within the MID region (approximately 56.64 × 103 km2), whereas the highest relative airspace coverage is achieved in the NAM (0.17%) and EUR (0.16%) regions. In contrast, RNAV 2 compatibility exhibits substantially greater spatial availability across most continental regions, making NAM (3.05%) and EUR (1.85%) the leading regions worldwide. RNAV 5 performance shows even broader progress, with compatible airspace extending over 24.7% in NAM and 23.92% in EUR. The influence of VOR/VOR-based navigation becomes particularly significant in supporting RNAV 10 operations, which are achievable within approximately 46% of the EUR and more than 42% of the NAM airspace. These results highlight both the regional disparities in RNAV capability and the continuing relevance of legacy VOR infrastructure in meeting lower-level navigation performance requirements.

5. Discussion

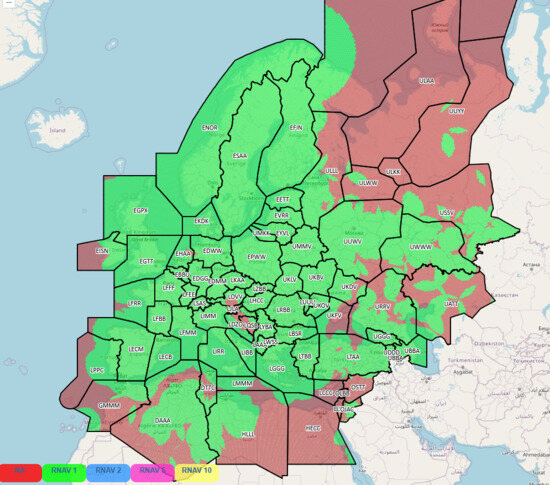

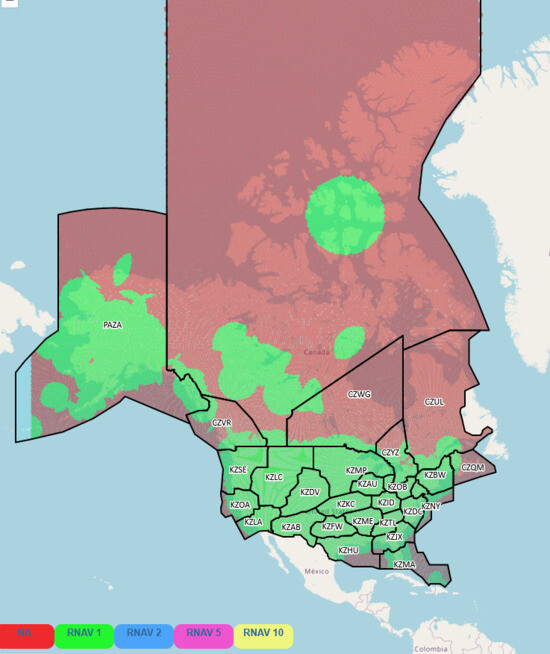

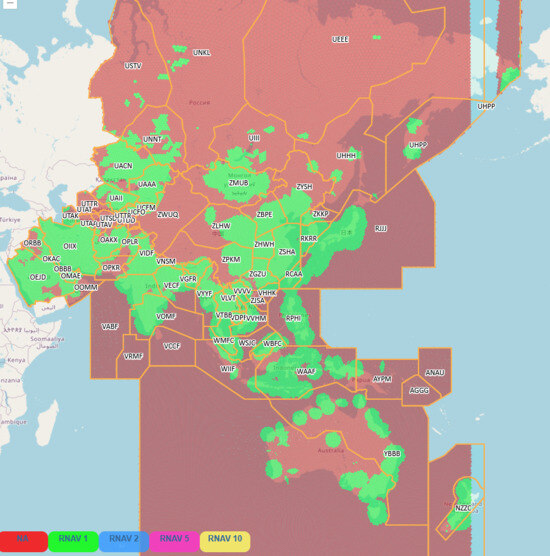

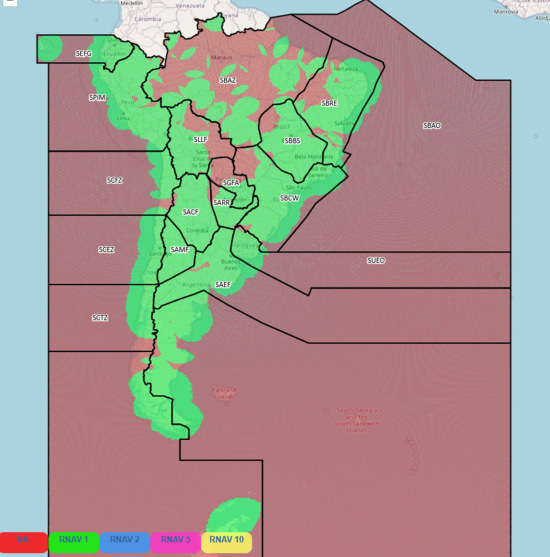

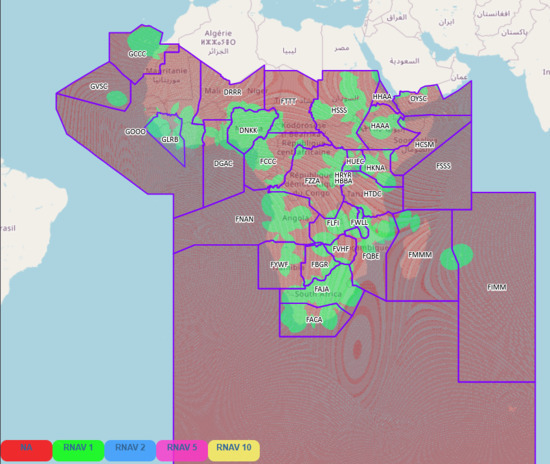

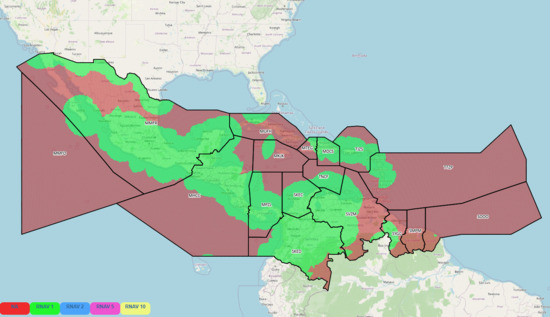

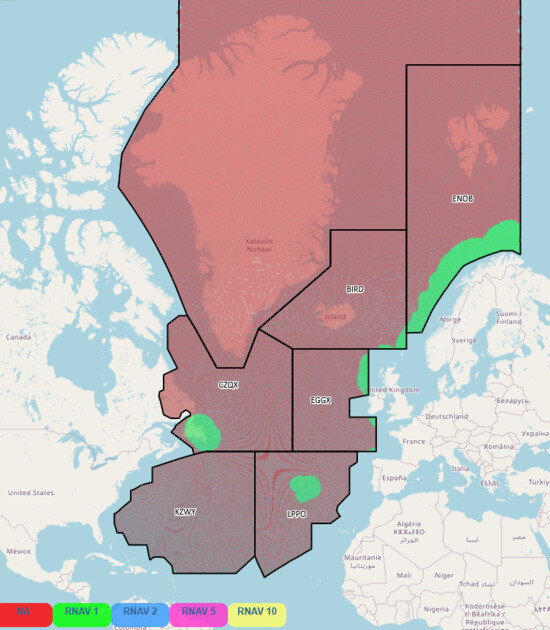

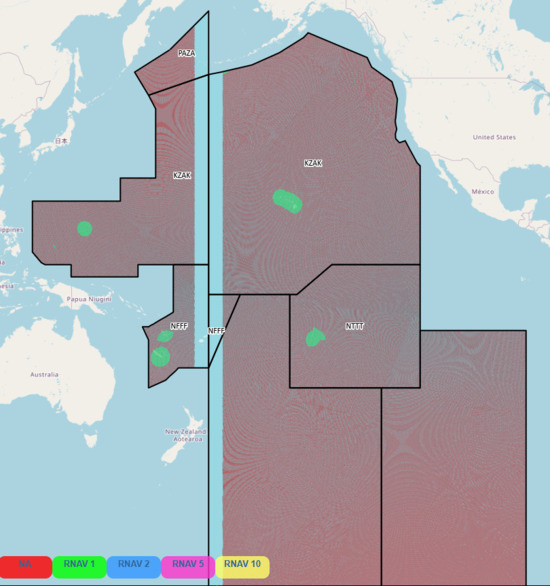

The nominal operation of the modern air transportation system is supported by a wide range of air navigation services. Among them, ground-based beacons of DME and VOR have played a crucial role in ensuring reliable aircraft navigation throughout the long history of civil aviation. Today, ground-based navigation aids networks by continuing to provide a reliable backup capability, representing the final layer of positioning integrity and security within the global navigation infrastructure. The results of the present analysis emphasize the critical importance of the DME network in maintaining global positioning continuity. Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22 present the outcomes of a comprehensive assessment of the PBN implementation status worldwide, based on the spatial compatibility of RNAV 1 operations across global airspace.

Figure 15.

RNAV 1 implementation status in Europe.

Figure 16.

RNAV 1 implementation status in the North American region.

Figure 17.

RNAV 1 implementation status in the Middle East region.

Figure 18.

RNAV 1 implementation status in the South American region.

Figure 19.

RNAV 1 implementation status in the Africa-Indian Ocean region.

Figure 20.

RNAV 1 implementation status in the Caribbean region.

Figure 21.

RNAV 1 implementation status in the North Atlantic region.

Figure 22.

RNAV 1 implementation status in the Pacific region. Source: Own elaboration of authors.

The green regions in Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22 indicate areas where RNAV 1 operations are fully supported by DME/DME positioning method. Consequently, even under conditions of strong GNSS interference, these areas are not expected to experience a significant impact on the safety of air transportation for aircraft equipped with DME/DME navigation systems. The total area of airspace compliant with RNAV 1 requirements using DME/DME positioning is approximately 103 × 106 km2, representing about 20.2% of global airspace. The spatial distribution of these regions demonstrates that most high-traffic areas are effectively covered by DME/DME services.

The VOR/DME network primarily supports RNAV 1 operations in proximity to ground stations, covering only 3.45% of global airspace. However, it provides a significant contribution to RNAV 5 and RNAV 10 navigation, ensuring coverage of 23.61% and 25.75% of global airspace, respectively. This indicates that the VOR/DME system continues to play an important role in maintaining reliable air navigation services, particularly as a backup to DME/DME.

The VOR/VOR positioning method, in contrast, demonstrates limited compatibility with RNAV 1 operations, covering only 180 × 103 km2 of global airspace. Nevertheless, it remains capable of supporting RNAV 10 operations within approximately 13.48% of the total airspace.

A comparative summary of the service areas for all three positioning methods DME/DME, VOR/DME, and VOR/VOR is presented in Table 8, compiled using the data from Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 8.

Implementation status of RNAV supported by different methods.

The results of the overall analysis clearly indicate that the DME/DME positioning method provides RNAV 1 compliance within approximately 20.2% of global airspace. In comparison, the VOR/DME configuration demonstrates effective coverage for RNAV 5 operations across 23.61% of airspace, while the VOR/VOR network remains applicable primarily within the oceanic region, supporting RNAV 10 navigation within 13.48% of the total global airspace.

It should be noted that obtained results are valid not only for FL150 but for any altitudes in the range from FL120 to FL180. Results for altitudes above FL180 will be different due to the reduced number of available navigation aids. DME types of Low Altitude and DME Low became unavailable above FL180, but overall network coverage will be compensated by using a significantly wider maximum operational range up to 130 NM for levels below FL450.

To date, there have been no comprehensive studies in the scholarly literature that systematically examine the spatial distribution of RNAV 1 capability across different airspace regions. Accordingly, the findings presented in this study contribute new insights into the global architecture of conventional navigation systems, offering valuable implications for both ICAO regional infrastructure planning and ANSPs. These results are particularly relevant in the context of growing concerns regarding GNSS interference, underscoring the strategic importance of maintaining and optimizing ground-based navigation networks as a resilient component of the future aviation navigation system.

6. Conclusions

Networks of ground-based radio navigation aids remain a vital component of modern air navigation services, supporting the operational reliability and safety required by aviation authorities worldwide. At present, more than 4639 certified radio navigation beacons are in use globally to ensure the continuity of air navigation services.

The article contributes to the development of theoretical aspects of air navigation by providing methodology of comprehensive network performance evaluation, including network topology analysis with the theory of graphs, estimation availability of GRNA network, reliability analysis (PFFO and POF), and evaluation accuracy of positioning by pairs of GRNAs (DME/DME, VOR/DME, and VOR/VOR methods).

The approach proposed in this study introduces a novel framework for analyzing the global network of navigation aids based on the spatial partitioning of airspace into computationally adaptive cells, adjustable to the desired level of resolution. This representation enables an efficient evaluation of network performance and facilitates the aggregation of spatial data. The key advantage of the proposed methodology lies in its ability to visualize the spatial distribution of achievable performance parameters for each network, which is essential for assessing navigation service quality and supporting performance-based planning.

A proposed algorithm could be useful for ANSP to evaluate the quality of services provided for airspace users, and for international organizations work on ensuring the safety of air navigation in a particular region.

The practical contribution of the article is that obtained results were aggregated according to the administrative regions of the ICAO, which allows for the evaluation of PBN implementation progress by each ICAO regional body. The analysis revealed that European (EUR) and North American (NAM) regions currently maintain the most developed networks of DME and VOR facilities, whereas the Pacific (PAC) and North Atlantic (NAT) regions, comprising predominantly oceanic airspace, exhibit the lowest density of navigation aids. This study is the first to evaluate GRNA performance based on the administrative regions of ICAO.

Evaluation of service coverage demonstrated that the global DME network provides navigation services over approximately 148 × 106 km2, corresponding to 29.17% of the available airspace, while the VOR network covers around 133.99 × 106 km2 (26.27%). These findings confirm that the DME network constitutes the most effective infrastructure for ensuring backup positioning capabilities in civil aviation. Among all analyzed configurations, only the DME/DME positioning method offers sufficient accuracy and coverage to support RNAV 1 operations on a global scale.

Current status (on October 2025) of PBN implementation shows that the optimized DME network meets RNAV 1 requirements over approximately 103 × 106 km2, representing more than 20% of global airspace. Co-located VOR/DME installations remain a useful option for short-range navigation, effectively supporting RNAV 5 operations over 120 × 106 km2 (about 23% of global airspace). However, the limited angular accuracy inherent to VOR systems prevents their use in meeting RNAV 1 criteria, rendering standalone VOR networks unsuitable for modern PBN applications.

The global DME network currently consists of 3676 operational nodes, providing about 29% overall coverage, while the VOR network includes 2783 nodes, achieving roughly 26% coverage. Nevertheless, the proportion of airspace that satisfies RNAV 1 or RNAV 2 requirements using VOR/VOR navigation remains negligible compared to DME/DME-based positioning. Consequently, VOR/VOR navigation can only be regarded as a viable option for oceanic operations, where RNAV 10 performance (with coverage above 13%) remains acceptable.

Taken together, these results indicate that the role of VOR/VOR navigation in future air traffic management will continue to decline. In contrast, the DME network provides a robust and globally consistent foundation for backup navigation capabilities and the long-term support of PBN objectives within the evolving framework of global air navigation services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.O.; methodology, I.O.; software, I.O.; validation, N.K. and I.O.; formal analysis, M.Z.; investigation, M.Z.; resources, M.Z.; data curation, N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.O.; writing—review and editing, N.K. and M.Z.; visualization, N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy of local ANSP.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFI | Africa-Indian Ocean region |

| AIP | Aeronautic Information Publication |

| ANSP | Air Navigation Service Provider |

| CAR | Caribbean region |

| DME | Distance Measuring Equipment |

| ECEF | Earth-Centered, Earth-Fixed coordinate system |

| EUR | European region |

| FIR | Flight Information Region |

| FTE | Flight Technical Error |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GRNA | Ground-Based Radio Navigation Aids |

| ICAO | International Civil Aviation Organization |

| ILS | Instrument Landing System |

| MID | Middle East region |

| NAM | North American region |

| NAT | North Atlantic region |

| NDB | Non-Directional Beacon |

| NEU | North-East-Up reference frame |

| NSE | Navigation System Error |

| OLC | Open Location codes |

| PAC | Pacific region |

| PBN | Performance-Based Navigation |

| PFFO | Probability of failure-free operation |

| POF | Probability of failure |

| RNAV | Area navigation |

| SAM | South American region |

| SSVB | Standard service volume of beacon |

| TSE | Total System Error |

| UHF | Ultra High Frequency |

| UIR | Upper Information region |

| VHF | Very High Frequency |

| VOR | VHF Omnidirectional Range |

| WGS | World Geodetic System |

References

- Ewertowski, T.; Berlik, M.; Slawinska, M. The effectiveness of operational residual risk assessment: The case of general aviation organizations in enhancing flight safety in alignment with sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeronautical Telecomunications. Radio Navigation Aids. Annex 10 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, 8th ed.; ICAO: Montreal, Canada, 2023; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- ICAO. Performance-Based Navigation (PBN) Manual. Doc 9613, 5th ed.; ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Orban, J. Overview of GNSS Interference Risks in Transport Safety and Resilient Responses. Eng. Proc. 2025, 113, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussong, M.; Ghizzo, E.; Milner, C.; Garcia-Pena, A. GNSS performance degradation under meaconing in civil aviation: Pseudorange and position models. GPS Solut. 2025, 29, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviation Safety Reporting System. NASA. Available online: https://asrs.arc.nasa.gov/search/database.html (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Flightradar24. Available online: https://www.flightradar24.com (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Ostroumov, I.; Ivashchuk, O.; Kuzmenko, N. Preliminary Estimation of war Impact in Ukraine on the Global Air Transportation. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Advanced Computer Information Technologies (ACIT), Ruzomberok, Slovakia, 26–28 September 2022; pp. 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felux, M.; Figuet, B.; Waltert, M.; Fol, P.; Strohmeier, M.; Olive, X. Analysis of GNSS disruptions in European Airspace. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Technical Meeting of the Institute of Navigation, Long Beach, CA, USA, 24–26 January 2023; pp. 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figuet, B.; Waltert, M.; Felux, M.; Olive, X. GNSS jamming and its effect on air traffic in eastern Europe. Eng. Proc. 2022, 28, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartl, S.; Kadletz, M.; Berglez, P.; Dusa, T. Findings from interference monitoring at a European airport. In Proceedings of the 34th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2021), Missouri, SL, USA, 20–24 September 2021; pp. 3683–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osechas, O.; Fohlmeister, F.; Dautermann, T.; Felux, M. Impact of GNSS-Band Radio Interference on Operational Avionics. Navig. J. Inst. Navig. 2022, 69, navi.516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roli, J.; Kumar, C.S.; Om, P. Distinctive navigational approach—A dead reckoning for aircraft co-ordinate estimation. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2855, 020003. [Google Scholar]

- Ostroumov, I.V.; Kuzmenko, N.S. Risk Analysis of Positioning by Navigational Aids. In Proceedings of the Signal Processing Symposium (SPSympo), Krakow, Poland, 17–19 September 2019; pp. 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroumov, V.; Kuzmenko, N.S.; Marais, K. Optimal Pair of Navigational Aids Selection. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Methods and Systems of Navigation and Motion Control (MSNMC), Kiev, Ukraine, 16–18 October 2018; pp. 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasidi, A.Z.; Ali, D.M.; Ya’acob, N.; Yusof, A.L.; Ametefe, D.S. Performance Measurement of Tactical Radio Station Deployment Using Very High Frequency (VHF) in Suburban Area Environment; Science & Technology Research Institute for Defence (STRIDE): Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tooley, M.; Wyatt, D. Aircraft Communications and Navigation Systems; Routledge: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Berz, G.E.; Bredemeyer, J. Qualifying DME for RNAV use. In Proceedings of the 15th International Flight Inspection Symposium, Oklahoma, OK, USA, 24–27 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- European ATM Master Plan, 2025 Edition, SESAR. Available online: https://www.sesarju.eu/MasterPlan2025 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Next Generation Air Transportation System (NextGen). NextGen Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2024. FAA. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/nextgen (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Lo, S.; Chen, Y.H.; Enge, P.; Peterson, B.; Erikson, R.; Lilley, R. Distance measuring equipment accuracy performance today and for future alternative position navigation and timing (APNT). In Proceedings of the 26th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS 2013), Nashville, TN, USA, 16–20 September 2013; pp. 711–721. Available online: https://www.ion.org/publications/abstract.cfm?articleID=11298 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Espen, M.; Schafer, M.; Vitan, V.; Berz, G.; Eichhorn, R.; Schmitt, J. Old but Gold: Evaluating the Accuracy and Integrity of DME Based on Real-World Measurements. In Proceedings of the AIAA DATC/IEEE 43rd Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Diego, CA, USA, 29 September–3 October 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Park, S.; Lee, S.; Seo, J.; Kim, E. Toward High Accuracy DME for Alternative Aircraft Positioning: SFOL Pulse Transmission in High-Power DME. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 15087–15097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, E.; Seo, J. SFOL DME pulse shaping through digital predistortion for high-accuracy DME. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 58, 2616–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitan, V.; Berz, G.; Saini, L.; Arethens, J.P.; Belabbas, B.; Hotmar, P. Research on alternative positioning navigation and timing in Europe. In Proceedings of the 2018 Integrated Communications, Navigation, Surveillance Conference (ICNS), Herndon, VA, USA, 22 April 2018; pp. 4D2-1–4D2-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroumov, I.V.; Kuzmenko, N.S. Compatibility analysis of multi signal processing in APNT with current navigation infrastructure. Telecommun. Radio Eng. 2018, 77, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroumov, I.V.; Marais, K.; Kuzmenko, N.S. Aircraft positioning using multiple distance measurements and spline prediction. Aviation 2022, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osechas, O.; Kujur, B.; Khanafseh, S. A Way Forward for DME to Support RNP. In Proceedings of the Integrated Communications, Navigation and Surveillance Conference (ICNS), Brussels, Belgium, 8–10 April 2025; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Milner, C.; Macabiau, C.; Estival, P. Multi-DMEs for alternative position, navigation and timing (A-PNT). J. Navig. 2022, 75, 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Milner, C.; Macabiau, C.; Estival, P.; Zhao, P. Performance-based multi-DME station selection. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 6299–6312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroumov, I.V.; Kuzmenko, N.S. Accuracy assessment of aircraft positioning by multiple Radio Navigational aids. Telecommun. Radio Eng. 2018, 77, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osechas, O.; Zampieri, G.; Weaver, B.; Felux, M.; Dehaynain, C.; Berz, G.; Scaramuzza, M. A standardizeable framework enabling DME/DME to support RNP. In Proceedings of the 35th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2022), Denver, Colorado, 19–23 September 2022; pp. 2020–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitan, V.; Berz, G.; Osechas, O.; Scaramuzza, M.; Zampieri, G. Quantifying DME-N Multipath in the Context of PBN. In Proceedings of the International Flight Inspection Symposium (IFIS), Durban, ZA, USA, 20–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ostroumov, I.V.; Kuzmenko, N.S. Accuracy improvement of VOR/VOR navigation with angle extrapolation by linear regression. Telecommun. Radio Eng. 2019, 78, 1399–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fang, K.; Lan, X.; Zhong, K. Integrating LEO Satellite Signal Doppler Measurements and DME/VOR for enhanced GNSS-Free Positioning and Fault Detection. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Technical Meeting of the Institute of Navigation, Long Beach, CA, USA, 27–30 January 2025; pp. 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. Investigation of APNT optimized DME/DME network using current state-of-the-art DMEs: Ground station network, accuracy, and capacity. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium, Myrtle Beach, SC, USA, 23–26 April 2012; pp. 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromboni, P.D.; Palmerini, G.B. An algorithm to rationalize a DME network as a backup for GNSS aircraft navigation. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2014, 34, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. Analysis of DME/DME navigation performance and ground network using stretched-front-leg pulse-based DME. Sensors 2018, 18, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topkova, T.; Pleninger, S.; Hospodka, J.; Kraus, J. Evaluation of DME network capability using combination of rule-based model and gradient boosting regression. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2024, 119, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroumov, I.; Kuzmenko, N. Configuration Analysis of European Navigational Aids Network. In Proceedings of the Integrated Communications Navigation and Surveillance Conference (ICNS), Dulles, VA, USA, 20–22 April 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroumov, I.V.; Ivannikova, V.; Kuzmenko, N.S.; Zaliskyi, M. Impact analysis of Russian-Ukrainian war on airspace. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2025, 124, 102742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Transportation. FAA. U.S. Terminal and En Route Area Navigation (RNAV) Operations, Advisory Circular no. 90-100A; U.S. Department of Transportation. FAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) Basic with Change 1. US Department of Transportation. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- ICAO. World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS-84) Manual. Doc 9674, 2nd ed.; ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Eurocontrol. Coordinate Reference Systems Basic User Guide. In WGS 84, ITRS, ETRS89, Coordinate Transformations and Data Origination; Eurocontrol: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ICAO. Directives to Regional Air Navigation Meetings and Rules of Procedure for Their Conduct (Doc 8144), 6th ed.; ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Azri, S.; Ujang, U.; Anton, F.; Mioc, D.; Rahman, A.A. Review of spatial indexing techniques for large urban data management. In Proceedings of the International Symposium & Exhibition on Geoinformation (ISG), Kuala Lumpur, Malasia, 24–25 September 2013; pp. 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, H.; Yu, B.; Wu, J.; Li, B.; Zhao, H. Spatial indexing of global geo-graphical data with HTM. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Geoinformatics, Beijing, China, 18–20 June 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Location Code Specification. Available online: https://github.com/google/open-location-code/blob/main/docs/specification.md (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Aini, A.N.; Dewantari, O.A.; Mandala, D.P.; Bisri, M.B. An Enhanced Earthquake Risk Analysis using H3 Spatial Indexing. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1245, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hexagonal Hierarchical Geospatial Indexing System Specification. Available online: https://h3geo.org (accessed on 18 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).