Abstract

The incorporation of Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (BFRP) materials marks a significant advancement in the adoption of sustainable and high-performance technologies in structural engineering. This study investigates the flexural behavior of four-meter, two-span continuous reinforced concrete (RC) beams of low and medium compressive strengths (20 MPa and 32 MPa) strengthened or rehabilitated using near-surface mounted (NSM) BFRP ropes. Six RC beam specimens were tested, of which two were strengthened before loading and two were rehabilitated after being preloaded to 70% of their ultimate capacity. The experimental program was complemented by Finite Element Modeling (FEM) and analytical evaluations per ACI 440.2R-08 guidelines. The results demonstrated that NSM-BFRP rope application led to a flexural strength increase ranging from 18% to 44% ductility by approximately 9–11% in strengthened beams and 13–20% in rehabilitated beams, relative to the control specimens. Load-deflection responses showed close alignment between experimental and FEM results, with prediction errors ranging from 0.125% to 7.3%. This study uniquely contributes to the literature by evaluating both strengthening and post-damage rehabilitation of continuous RC beams using NSM-BFRP ropes, a novel and eco-efficient retrofitting technique with proven performance in enhancing structural capacity and serviceability.

1. Introduction

Concrete remains the most widely used construction material due to its high durability, resistance to fire, and ability to perform well under harsh environmental conditions [1,2,3]. Despite these advantages, a large portion of existing reinforced concrete (RC) structures are currently facing serviceability and safety challenges. Many buildings constructed in the past decades are approaching the end of their expected design life and are increasingly exposed to deterioration caused by fire, cyclic loading, corrosion of reinforcement, and aggressive environmental actions [4,5,6,7]. These issues have created a pressing need for reliable strengthening and rehabilitation strategies to ensure the safety and extended service life of concrete structures.

Over the years, numerous methods have been introduced to enhance the load-carrying capacity of RC members while minimizing disruption to occupants. Conventional strengthening approaches, such as the installation of external steel frames or steel jacketing, have proven effective but often suffer from drawbacks, including added structural weight, increased construction costs, and labor-intensive installation [8].

In contrast, advanced composite materials, particularly fiber-reinforced polymers (FRPs), have emerged as promising alternatives for structural rehabilitation. FRP composites are lightweight, corrosion-resistant, and easy to install, offering significant improvements in both flexural and shear capacities of RC members [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

Among the various FRP strengthening techniques, the Near-Surface Mounted (NSM) method has demonstrated superior performance and practicality. In this technique, grooves are cut into the concrete cover and FRP bars or ropes are bonded inside using epoxy adhesives. Compared to externally bonded FRP sheets, the NSM approach offers stronger bond performance, higher resistance to debonding, and better protection of reinforcement against environmental exposure [10]. This has made the NSM strengthening method a widely investigated technique for improving the flexural performance of RC beams.

While carbon (CFRP) and glass (GFRP) fibers have traditionally dominated research and practice, basalt fiber-reinforced polymer (BFRP) materials have recently attracted attention as an efficient and sustainable alternative. Basalt fibers are produced from abundant natural volcanic rock, making them less energy-intensive and more cost-effective to manufacture compared to carbon fibers. They also exhibit superior tensile strength compared to glass fibers and higher strain capacity than carbon fibers, offering an advantageous balance between mechanical performance and affordability [19,20,21,22,23]. Because of these characteristics, BFRP composites present a favorable strength-to-cost ratio and are increasingly considered in structural rehabilitation applications.

Experimental studies on BFRP sheets, bars, and grids have demonstrated notable improvements in the flexural and shear behavior of RC members. For example, research has shown that BFRP sheets can significantly increase shear and flexural strength and delay crack formation, while NSM-BFRP bars enhance flexural resistance and load recovery in beams exposed to elevated temperatures [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Further investigations have also highlighted the positive impact of BFRP strips, grids, and wrapping systems in boosting stiffness, ductility, and ultimate load capacity [32,33,34]. These findings confirm the potential of BFRP materials to provide comparable or even superior performance relative to conventional FRP systems.

Nevertheless, important research gaps remain. Most available studies have focused on small-scale specimens, shear-strengthening applications and alternative BFRP forms (sheets, bars, grids), which differ in terms of bond mechanism, stress transfer, and constructability compared to ropes, while relatively few investigations have addressed the use of BFRP materials for enhancing the flexural behavior of full-scale RC beams, particularly in continuous configurations. Moreover, although CFRP ropes have been the subject of several experimental programs, the application of BFRP ropes remains underexplored despite their lower cost, easier installation, and improved long-term durability when embedded within the concrete matrix. Bridging this gap is critical for advancing the practical adoption of BFRP reinforcement in large-scale rehabilitation projects.

We aim to address these gaps by experimentally investigating the flexural performance of full-scale continuous RC beams constructed with different concrete strengths and strengthened using NSM-BFRP ropes. This research contributes to the growing body of knowledge on sustainable strengthening materials by evaluating the structural efficiency of BFRP ropes under realistic conditions. The findings are expected to provide engineers and designers with valuable insights into the viability of BFRP ropes as a cost-effective, durable, and environmentally friendly alternative to conventional FRP systems, thereby advancing the implementation of innovative strengthening solutions in structural engineering practice.

2. Materials and Procedures

2.1. Concrete and Steel Reinforcement

Normal-, medium-, and low-strength concrete was used to cast all beam samples [35]. Further details about the mixes are outlined in Table 1 as provided by the manufacturer. Compressive strength tests conducted at 28 days on three cylinders per mix resulted in average values of 20.23 MPa and 32.2 MPa. Beam specimens were reinforced with deformed high-yield steel bars complying with ASTM A615M [36], using 12 mm and 14 mm diameters. The 12 mm bars had an average yield strength of 500 MPa and an ultimate tensile strength of 703 MPa, while the 14 mm bars showed values of 535 MPa and 755 MPa, respectively.

Table 1.

Mix Design Parameters for Low- and Medium-Strength Concrete.

2.2. BFRP Materials

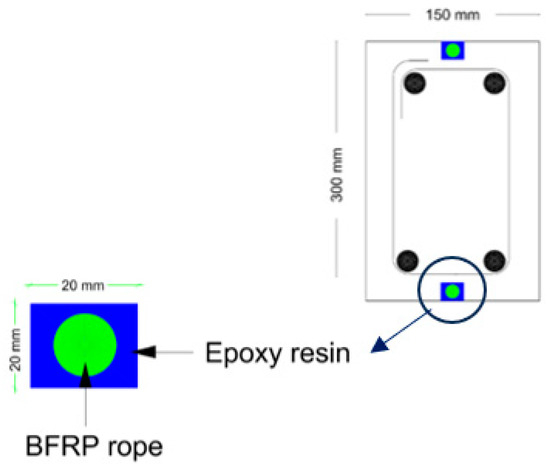

In this investigation, BFRP ropes were utilized, as depicted in Figure 1, to strengthen and rehabilitate the continuous RC beams. The supplier’s comprehensive specifications for BFRP ropes are delineated in Table 2.

Figure 1.

BFRP ropes.

Table 2.

BFRP ropes’ properties.

2.3. Epoxy Resin

To ensure proper adhesion between the BFRP and the concrete surface, to prevent potential debonding during testing, adhesives compatible with each material type were selected. Sikadur®-31, provided by the manufacturer, was used specifically for the BFRP ropes.

2.4. Beam Specimens

2.4.1. Testing Scheme

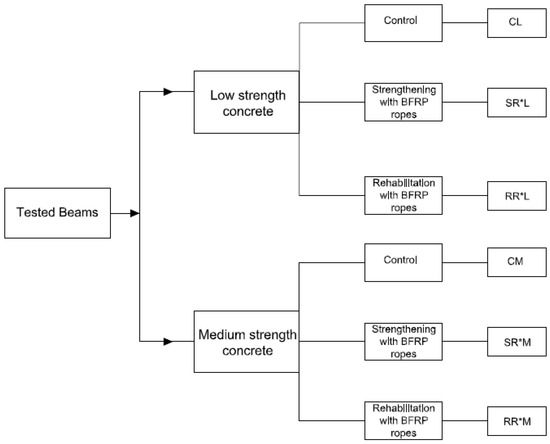

Six beams were subjected to testing, three cast with low-strength and three with medium-strength ready-mixed concrete. The beams were categorized into three groups: Group I consisted of a control beam without any BFRP reinforcement; Group II included three beams that were repaired using NSM-BFRP ropes; and Group III comprised three beams that were strengthened with NSM-BFRP ropes. The grouping is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Test description.

2.4.2. Details of Beam Reinforcement

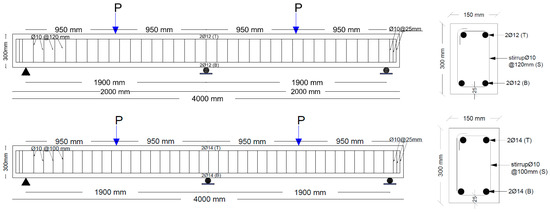

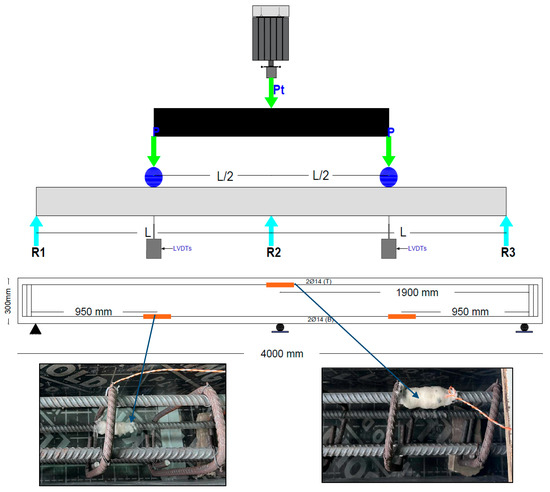

Six large-scale continuous RC beams were cast and tested to the point of failure. The beams were designed according to ACI 318M-11 [37], as depicted in Figure 3. The ratio of tensile steel reinforcement to compression steel reinforcement (ρ/ρ′) was kept constant at 1 throughout the entire length of each beam. To avoid shear failure, closed nominal stirrups with a 10 mm diameter were consistently arranged at 120 mm and 100 mm for low- and medium-strength, respectively, calculated using the actual concrete compressive strengths (f′c = 20 MPa and 32 MPa) and rebar yield strengths (fy = 420 MPa).

Figure 3.

Details of reinforcement in tested beams.

2.4.3. Strengthening and Rehabilitation Scheme

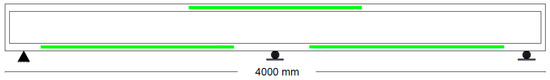

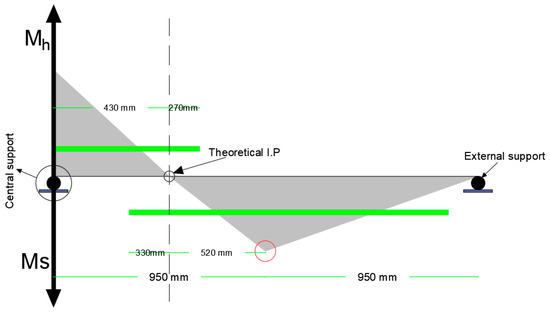

Figure 4 shows the configuration used for strengthening and repairing of the beams. In this experimental setup, BFRP ropes were embedded in regions subjected to positive and negative bending moments, with reinforcement continued past the expected points of contraflexure (zero moment) to ensure continuity, as shown in Figure 5. This arrangement was designed to ensure continuous reinforcement across critical zones, enhancing structural performance under flexural demands.

Figure 4.

Strengthening and rehabilitation pattern.

Figure 5.

BFRP layout in strengthened and repaired beams.

2.4.4. Preparation of Grooves and the Procedure for Strengthening and Rehabilitation

Before attaching the BFRP ropes to the beams, the surfaces must be cleaned thoroughly to remove dust or loose materials. A groove with dimensions of 20 mm width by 20 mm thickness was drilled into the beams using an electric saw machine for the BFRP ropes as shown in Figure 6. The groove was then partially filled with epoxy resin as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, the BFRP rope was installed in the grove and covered with epoxy. For strengthening, the BFRP ropes were directly placed into the beam’s grooves. Prior to rehabilitation, the beams were pre-loaded to 70% of the ultimate load capacity (the maximum load the beam can carry before failure, corresponding to the point at which significant flexural cracks develop, and the beam can no longer sustain additional loading, the ultimate load of each RC beam was determined experimentally by applying a monotonically increasing load until failure. The load was applied in increments of 10 kN/s, and the beam response was continuously monitored until a sudden drop in load-carrying capacity indicated ultimate failure.) of the control beam before the BFRP ropes were installed. The rehabilitated beams were then reloaded to failure under the same conditions. Specialized machinery was employed to smooth the surface following the application of basalt fiber. The beams were left for one week to facilitate the curing and enhancement of the epoxy after the installation of BFRP ropes. The BFRP ropes were applied both at the top and bottom of the beams to strengthen and rehabilitate them, taking into account the positive and negative moments experienced during flexural loading.

Figure 6.

Groove size.

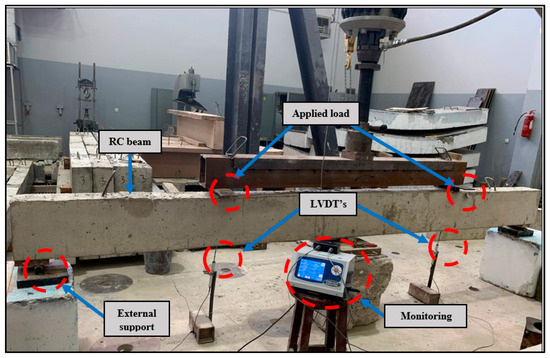

2.5. Test Setup

Figure 7 shows the test setup detail; each beam was tested under two-point loads. The experiment recorded the total applied load (Pt = 2P), mid-span deflection (δ), and steel strain (εs) throughout the loading process.

Figure 7.

Test setup.

The load was applied to the beams using a hydraulic jack at a rate of 10 kN per second. Two vertical linear variable differential transducers (LVDTs) were utilized to measure the vertical deflection at the mid-span of each beam. Internal electrical strain gauges were installed on the reinforcement bars to measure strains at different locations, such as mid-span and central support of the beams. Figure 8 depicts the positions of the strain gauges. To ensure precise measurement, all strain gauges were coated with polyurethane material to provide protection against moisture and dust. While this does not make the gauges perfectly waterproof, it provides sufficient protection for the duration of the experimental tests under normal laboratory conditions. During testing, each beam was loaded until the load-deflection curve reached its peak, ensuring that the complete load-carrying capacity of the beam was reached. At this stage, the beams exhibited visible cracking patterns and large mid-span deflections, confirming ultimate failure.

Figure 8.

Strain gauges.

3. Results and Discussion

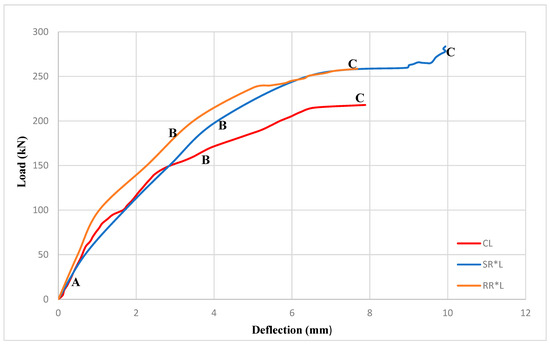

3.1. Load Deflection Response

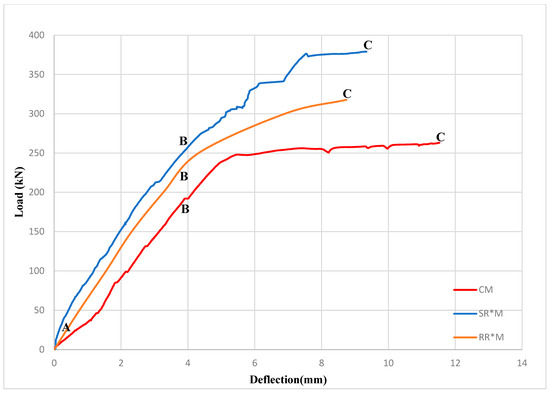

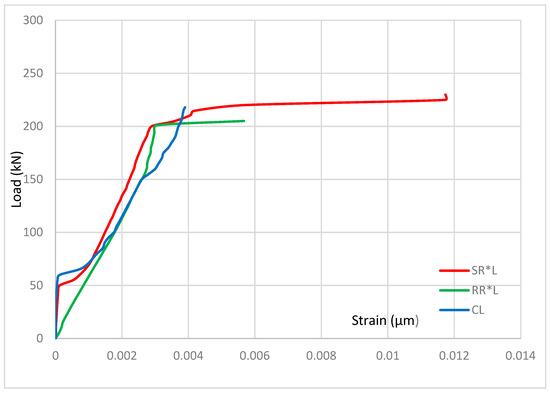

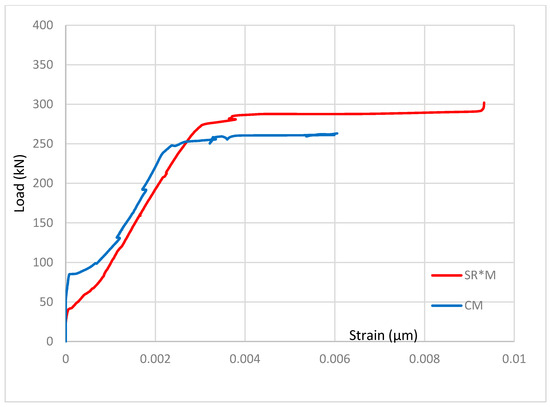

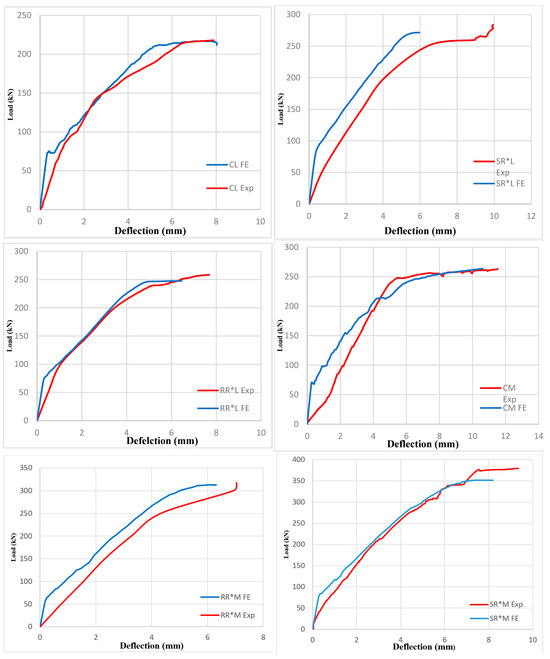

Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the loads versus mid-span deflection, measured using LVDTs, for beams CL, SRL, RRL, CM, SRM, and RRM. Key stages denoted as points A, B, and C mark significant milestones such as crack initiation, steel yielding, and maximum capacity of the beams. These phases were determined by observing variations in the gradient of the curves. In general, the NSM-BFRP beams showed increased yielding and ultimate loads, relative to the control beam, and the cracking load stayed stable.

Figure 9.

Load displacement curves for low-strength concrete samples.

Figure 10.

Load displacement curves for medium-strength concrete samples.

Key stages denoted as Points A, B, and C represent crack initiation, steel yielding, and maximum load capacity, respectively. Point A corresponds to the load at which the first visible surface crack appeared. Point B marks the yielding of the tensile reinforcement, identified when the measured strain in the reinforcement exceeded the theoretical yield strain, approximately εy ≈ 0.002. This was verified by strain gauge measurements. Point C corresponds to the maximum load capacity of the beam, defined as the absolute peak load recorded by the load cell. In the initial elastic phase, the presence of BFRP ropes had a limited effect on the overall stiffness of both strengthened and rehabilitated beams, as all specimens demonstrated comparable structural responses. However, prior to the yielding of the tensile steel reinforcement, beams reinforced with NSM-BFRP ropes exhibited noticeably higher stiffness and increased yield loads compared to the control beam, for all concrete strength. Following the onset of steel yielding, the NSM-BFRP beams showed an increase in load-carrying capacity, ultimately achieving greater ultimate loads than the control specimen. This highlights the significant contribution of BFRP ropes in enhancing post-yield performance. These findings suggest that NSM-BFRP ropes functioned effectively as additional tensile reinforcement, enhancing the overall structural response by reducing stiffness deterioration.

3.2. Overall Capacity and Failure Scenarios

In this study, beams designated for rehabilitation were subjected to preloading up to 70% of their ultimate load capacity before strengthening. This loading level was chosen to replicate realistic service conditions where RC members experience significant cracking and stiffness degradation before intervention. The selected preloading ratio is consistent with prior research [38,39], which suggested that preloading in the range of 60–75% offers a practical balance between inducing representative damage while preserving the structural integrity required for successful strengthening.

In this part, the peak load values and maximum deflections at the mid-span of the tested beams were assessed. At the central support, the yielding in the tensile steel reinforcement was precisely captured through strain gauge measurements.

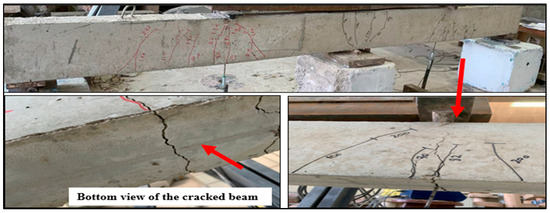

The CL beam, cast using low-strength concrete, demonstrated a ductile flexural failure mechanism. The response is characterized by the formation of plastic hinges at both the mid-span and intermediate support zones, followed by concrete crushing in the compression zone, as illustrated in Figure 11. The beam sustained a maximum load of 218 kN, accompanied by a mid-span deflection of 7.88 mm (refer to Table 3). This behavior reflects the inherent limitations of low-strength concrete in moment redistribution, and ductility was maintained prior to failure. In comparison, the SRL beam strengthened with NSM-BFRP ropes achieved a 30.14% increase in load-carrying capacity over the control. Throughout testing, the SRL beam displayed a fully ductile response, with crack formation observed at the mid-span and intermediate support, yet no signs of concrete cover separation or debonding were detected. It is worth mentioning that loading was terminated once beams reached ultimate capacity and excessive deflections, to avoid catastrophic collapse of setup and equipment. Therefore, no debonding/rupture was observed at applied loads. This outcome highlights the successful application of NSM-BFRP ropes, which not only boosts the structural strength and ductility of the RC beam but also maintains strong bonding between the BFRP ropes and the concrete surface. The load on beam was not increased up to BFRP rope debonding or rupture to prevent sudden catastrophic failure and ensure safe observation of deflection, cracking, and stress redistribution. The reported ultimate loads therefore represent the maximum capacity reached safely under the experimental procedure. During the experimental testing of the strengthened beams, no debonding or rupture of the BFRP ropes was observed, and the concrete cover remained intact throughout the loading process. The beams exhibited flexural failure characterized by gradual crack propagation until reaching the ultimate load. The continuous reinforcement along the beam’s length ensures an even distribution of strengthening effects, reducing the risk of localized stress buildup that could cause debonding or cover separation as shown in Figure 12. Although strain gauges were not used, the gradual crack propagation and consistent deflection along the beam span indicate that the strengthening effects of the continuous BFRP reinforcement were uniformly distributed. No localized debonding or premature failure was observed, confirming the effectiveness of the strengthening system along the entire span. The failure load increased to 283.7 kN, accompanied by a maximum deflection of 9.94 mm at midspan as shown in Table 3.

Figure 11.

Typical flexural ductile failure of CL.

Table 3.

Experimental and numerical results.

Figure 12.

Flexural ductile failure, without debonding of BFRP ropes of SR*L.

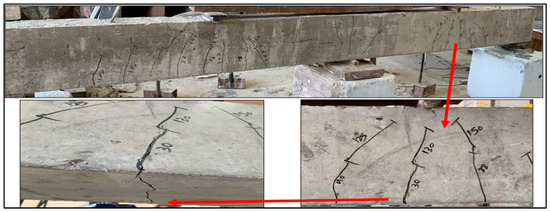

The RR*L beam showed an increase in flexural strength of approximately 18.62% compared to the control beam. The ultimate failure load recorded was 258.6 kN, with an ultimate vertical deflection at the midspan measuring 7.68 mm as shown in Table 3. The utilization of BFRP ropes as a rehabilitation material for low-strength concrete in flexural applications yielded a positive outcome in terms of rehabilitation efficacy. The failure mode observed in both cases was predominantly flexural, marked by the formation of plastic hinges at the mid-span and intermediate support regions. Importantly, no debonding or concrete cover separation was detected during testing, as depicted in Figure 13 and Figure 14. The absence of debonding/rupture can be attributed to the effective confinement provided by the surrounding concrete and adequate anchorage length of the ropes. It should be noted that the precise load level at which debonding or rupture might occur could not be identified in this study, since the beams reached their ultimate state before such phenomena were triggered. Further dedicated bond or rupture tests would be required to determine this threshold. The control beam (CM) also exhibited this typical flexural response. It sustained a maximum load of 263.25 kN and recorded a peak mid-span deflection of 11.52 mm.

Figure 13.

Flexural ductile failure, without debonding of BFRP ropes of RR*L.

Figure 14.

Flexural ductile failure of CM.

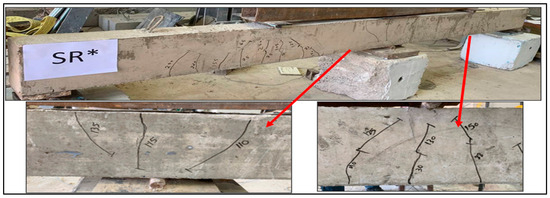

The SR*M beam underwent strengthening with NSM-BFRP, resulting in a significant 44% increase in its load-carrying capacity compared to the control beam. Throughout testing, the beam displayed a purely ductile failure, with flexural cracks emerging at both the midspan and the middle support, yet no debonding or separation of the concrete cover occurred. This underscores the successful implementation of NSM-BFRP ropes, which enhances both the structural strength and ductility of the RC beam while maintaining robust bonding between the BFRP ropes and the concrete surface. The continuous reinforcement along the beam’s span ensures uniform distribution of strengthening effects, mitigating the risk of localized stress accumulation that could lead to debonding or cover separation, as depicted in Figure 15. The failure load rose to 379 kN, accompanied by a maximum deflection of 9.34 mm at midspan, as shown in Table 3. The enhanced behavior is attributed to multiple mechanisms: the BFRP ropes act as supplementary tensile reinforcement, improving stress redistribution along the span; the confinement effect delays crack propagation and concrete crushing; and the continuous rope placement ensures uniform strengthening, preventing localized overstress.

Figure 15.

Flexural ductile failure, without debonding of BFRP ropes of SR*M.

The RR*M beam, initially subjected to a load equivalent to 70% of its ultimate capacity, underwent rehabilitation through the application of NSM-BFRP ropes. This intervention resulted in a notable increase in flexural strength, approximately 20.7% higher than that of the control beam. The beam’s ultimate failure load was recorded at 317.8 kN, accompanied by an ultimate deflection at the midspan measuring 8.74 mm, as detailed in Table 3. The adoption of BFRP ropes as a rehabilitation material for medium-strength concrete in flexural applications demonstrated positive outcomes in terms of rehabilitation effectiveness. It is noteworthy that the failure mode observed was flexural, characterized by the formation of flexural cracks at both the mid-support and midspan. Notably, there was no occurrence of debonding or separation of the BFRP ropes from the concrete cover, as depicted in Figure 16. The failure remained flexural, with cracks forming at both mid-support and mid-span, and no debonding or cover separation confirming the efficiency of NSM-BFRP ropes in rehabilitating preloaded beams.

Figure 16.

Flexural ductile failure, without debonding of BFRP ropes of RR*M.

Overall, the critical analysis of the strengthened and rehabilitated beams indicates that the application of NSM-BFRP ropes consistently enhances flexural capacity, ductility, and stress redistribution while preventing premature failures. The results demonstrate that careful rope placement, continuous reinforcement along the span, and bond quality are key factors in achieving both strength and ductility improvements.

3.3. Cracking Behavior

In both NSM and control beams, initial cracking occurred simultaneously at internal support and the middle span. With increasing the load, the cracks widened and moved to the compression zones, with new flexural cracks developing and spreading along the beams.

Before the tension steel reinforcement yielded, these flexural cracks did not extend into the filling material of any of the strengthened or repaired beams. Upon yielding of the steel reinforcement, flexural cracks oriented transversely were observed within the adhesive resin along the beam’s length, suggesting that the additional reinforcement (BFRP ropes) managed to crack up to the point of failure load. At failure, partial or complete concrete crushing was observed at the points of load and the central support in all beams.

3.4. Ductility Index

The ductility index was computed to gauge the ductility of both the strengthened and rehabilitated beams in comparison to the control beam. The summarized findings are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ductility index.

Equation (1) presents the ductility index equation, where and and the average mid-span deflections of the beam at ultimate and yielding loads, respectively.

Using NSM-BFRP ropes not only increases the flexural capacity of RC beams but also significantly enhances ductility, by approximately 9–13% in low-strength concrete beams (RR*L and SR*L) and 11–13% in medium-strength beams (RR*M and SR*M) compared to unstrengthened controls. This increase in ductility allows beams to sustain larger deflections and dissipate more energy before failure, an especially valuable trait in preventing brittle collapse. Importantly, improved ductility facilitates moment redistribution in continuous beams, a behavior supported in both experimental and modeling studies of FRP-strengthened continuous members [40,41]. Hybrid reinforcement using GFRP and steel has likewise been shown to enhance flexural stiffness, reduce crack width, and improve ductility under load, confirming the practical advantages of ductility enhancement [42]. Despite these benefits, many design guidelines remain conservative regarding moment redistribution in FRP-strengthened systems due to uncertainties about ductility and bond performance. The findings suggest that the ductility enhancements we observed could help bridge that gap, enabling safer and more efficient implementation of NSM-BFRP strengthening strategies in design practice. The ductility index of Beam RRL was observed to be slightly higher than that of Beam SRL, while Beams RRM and SRM exhibited very similar values. From a structural mechanics perspective, this outcome is expected because ductility, as reflected by the load–deflection response, is primarily governed by reinforcement behavior and failure mode rather than concrete compressive strength alone. Consequently, the ductility indices for both low- and medium-strength beams showed only modest differences, with the general characteristics of their curves remaining comparable under monotonic loading. The obtained ductility indices (µ = 2.0–2.42) align with previous FRP-strengthened beam studies [43]. Confirming that NSM-BFRP ropes provided a 9–20% enhancement in deformation capacity while maintaining flexure-governed, ductile behavior.

3.5. Load Strain Analysis of Tensile Reinforcement

As shown in Figure 17 and Figure 18, the strain values of tension reinforcing bars in beams made of low and medium-strength concrete are influenced by two distinct stages. The initial phase represents the concrete cracking load, while the subsequent phase marks the yielding of the tension steel reinforcement, influenced by the applied strengthening and rehabilitation methods. Initially, tensile strain in the reinforcement remains nearly zero until the concrete reaches its cracking load. However, once cracking initiates in the concrete sections, the tensile forces are primarily borne by the steel reinforcement and BFRP ropes, resulting in a sudden increase in their tensile strains. It is important to note that the strain gauges installed on the steel reinforcement in the RR*M sample were defective and did not provide accurate strain measurements. In Beam CL, the longitudinal reinforcement did not yield due to the early crushing of the low-strength concrete, which limited the beam’s flexural deformation capacity. For Beam RRL, the ultimate load after steel yielding was lower than that of Beam SRL. This is because, in the rehabilitated low-strength beam, the BFRP ropes primarily enhanced post-yield stiffness, but the concrete’s low strength restricted the ultimate load. In contrast, the strengthened beam SRL utilized both the original reinforcement and the BFRP ropes effectively, resulting in a higher post-yield load.

Figure 17.

Strain of steel in low-strength concrete samples.

Figure 18.

Strain of steel in medium-strength concrete samples.

This behavior highlights the fundamental role of concrete cracking in load redistribution within reinforced beams. In the initial stage, the concrete effectively resists tensile stresses, preventing significant strain development in the reinforcement. However, once cracking occurs, the concrete’s tensile contribution diminishes, and the load is transferred predominantly to the steel reinforcement and BFRP ropes, leading to a rapid increase in strain.

A comparison between low and medium-strength concrete beams reveals that the cracking load varies depending on concrete strength, with higher-strength concrete generally exhibiting delayed crack initiation due to its improved tensile resistance. Furthermore, the effectiveness of the strengthening and rehabilitation method becomes evident in the post-cracking phase, where the addition of BFRP ropes plays a crucial role in controlling strain development and delaying steel yielding.

The absence of accurate strain data in the RR*M sample due to defective gauges limits direct comparisons for this particular case. However, the overall trend suggests that the presence of BFRP ropes enhances load-bearing capacity by redistributing stresses, mitigating excessive strain in the steel, and potentially improving ductility.

3.6. The Effectiveness of Using NSM-BFRP Ropes

The application of NSM-BFRP ropes for strengthening and repairing low and medium-strength continuous RC beams led to an enhancement in both flexural strength and load-carrying capacity when compared to control beams. Additionally, the strengthened and rehabilitated beams exhibit superior ductility compared to the control beams. It is important to highlight that all beams failed due to flexure, without instances of debonding or separation of the concrete cover.

4. Numerical Investigation

Three-dimensional nonlinear finite element simulations were performed with the ABAQUS software 2020, suited to virtually represent the enhancement and restoration of two-span reinforced concrete beams employing NSM BFRP ropes.

4.1. ABAQUS Element Library Test Description

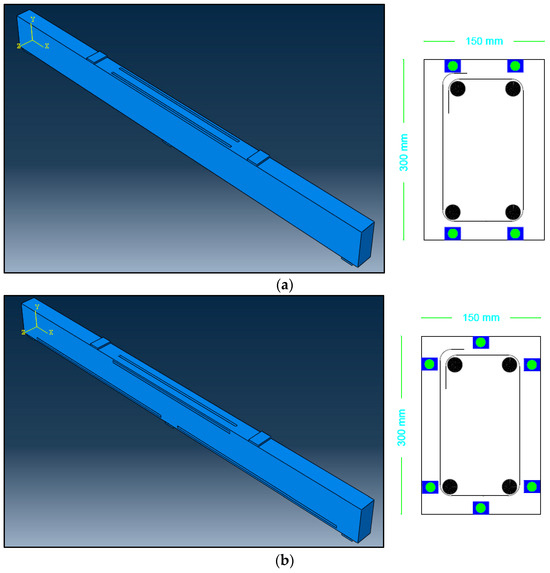

The simulation of the two-span RC beams was conducted using ABAQUS software. Initially, beam parts measuring 4000 mm in length, 150 mm in width, and 300 mm in height were created. Steel reinforcement and BFRP ropes were modeled as one-dimensional elements to replicate the test setup, including support plates and loading plates designed accordingly.

In Abaqus, the Step Module (the feature used to define the loading steps in the numerical model) is used to define analysis steps that control how loading and boundary conditions are applied during the simulation. For the present study, two steps were modeled: (i) a pre-load step with a very short duration of 1 × 10−10 s, introduced to replicate the initial pre-loading observed in the experimental rehabilitation procedure, and (ii) a monotonic loading step with a duration of 1 s, applied incrementally until the ultimate capacity of the beam was reached. This approach allowed the numerical model to accurately capture the experimental sequence while maintaining computational efficiency. This approach efficiently established initial conditions without significantly extending the analysis time.

Interactions were mostly configured as tie constraints, apart from the connection between concrete and reinforcement, which was defined as an embedded region with complete bonding and no slip. Boundary conditions were enforced, and loads were gradually applied to nodes along the centerline of the support plates at the bottom of the beam, mimicking roller and pin supports. The load application was controlled by displacement to ensure a gradual increase and prevent problems like velocity and acceleration that occur after surpassing maximum loads common in load-controlled situations. The maximum load applied in the numerical analysis for each beam was based on the ultimate capacity observed experimentally, the maximum load used for comparison in the numerical simulation was determined directly from the experimental load–deflection curves. It corresponds to the peak load sustained by the beam prior to the reduction in load-carrying capacity, which occurred due to concrete crushing in the compression zone or reinforcement yielding. Each simulation continued until the beam reached its peak load, ensuring that the numerical results accurately represent the flexural behavior up to failure.

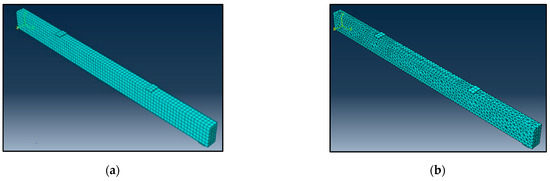

In the mesh module, a hexagonal cubic mesh was used for control beam samples, as these beams have regular geometries that are well-suited for structured meshing. Hexahedral elements offer high accuracy and computational efficiency for simple geometries, ensuring precise results with fewer elements. For grooved samples with NSM BFRP ropes, a tetrahedral pattern was employed to better handle the complex geometry and interfaces between the NSM-BFRP ropes and the surrounding material. Tetrahedral elements allow for more flexibility in meshing irregular shapes and enable finer local refinement where stress concentrations occur. The mesh types are depicted in Figure 19a and Figure 19b, respectively. A mesh size of 50 mm was used for the concrete domain in both types, determined through a mesh sensitivity study. This study examined element sizes ranging from 30 mm to 75 mm. The 50 mm element size was selected as it provided a suitable balance between computational efficiency and accuracy. Finer meshes (e.g., 30 mm) produced only marginal improvements in the prediction of peak loads (within 3%), while significantly increasing computational time. Coarser meshes (e.g., 75 mm) led to underestimation of the load-carrying capacity by up to 5%. Therefore, the selected 50 mm mesh size ensured stable and reliable simulation results, with minimal impact on the overall load-carrying behavior of the RC beams. This mesh setup also enabled effective visualization of crack patterns.

Figure 19.

(a) Hexahedral, (b) Hexahedral; Concrete mesh.

Output settings were modified to incorporate field and history outputs, with particular requests for load measurements as an integrated output section and deflection readings. After setting this up, the job was generated and submitted. The numerical results from the finite element analysis were subsequently compared with experimental data, concentrating on ultimate load, peak deflection, and modes of failure.

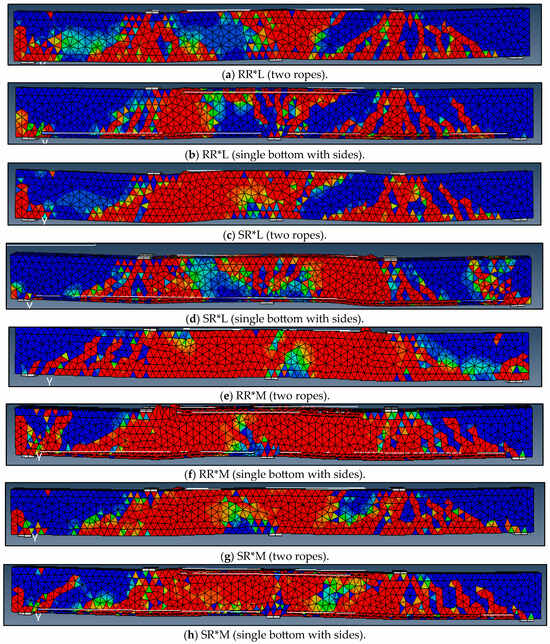

Our research expanded the FEM models and validated them against experimental data for consistent behavior. An alternative configuration using two BFRP ropes in place of one was explored, maintaining consistent lengths and placements. Additionally, side BFRP ropes were added parallel to steel reinforcement, complementing single BFRP ropes positioned at the beam’s top and bottom.

4.1.1. Model Parts

The model consists of six components: steel reinforcement, concrete, loading plate, support plate, top BFRP rope, and bottom BFRP rope. Detailed specifications for these components are provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Experimental and analytical results.

4.1.2. Materials

- Concrete

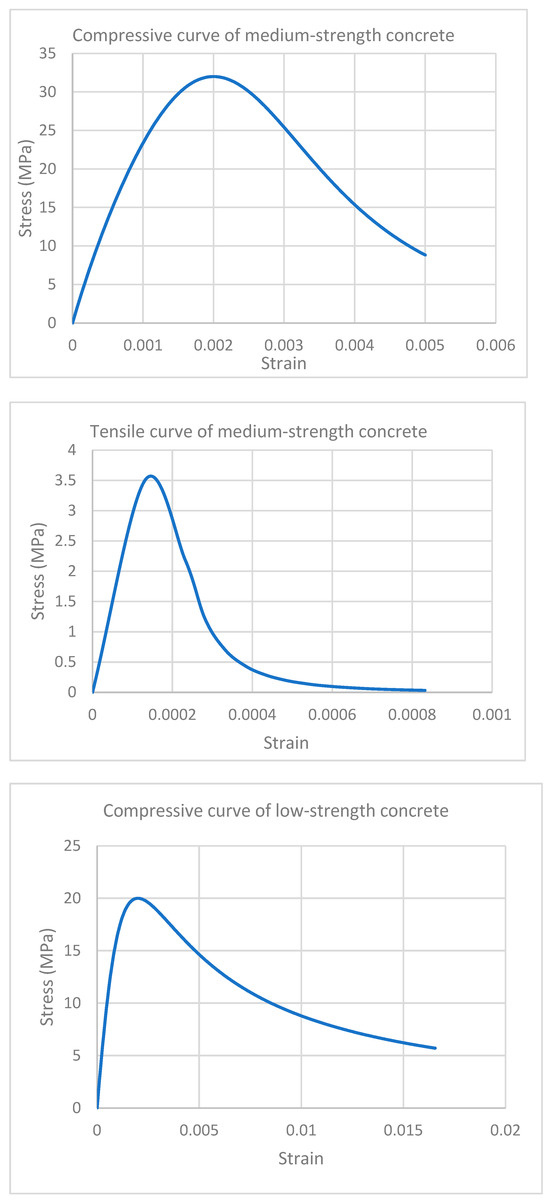

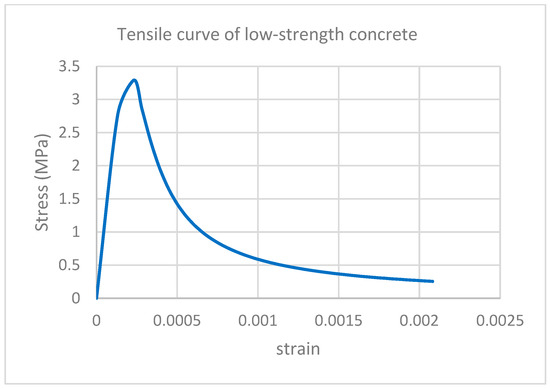

To capture the nonlinear behavior of concrete in RC beams, Tsai’s constitutive model was employed for low and medium-strength RC beams, which allows for realistic simulation of both tensile and compressive responses, including post-peak softening. The model incorporates strain-softening characteristics beyond peak stress, which are essential for representing the gradual loss of strength in the compression zone due to crushing, as well as cracking and tension stiffening effects in the tensile region. The stress–strain relationships used in this study were calibrated for medium and low-strength concrete, and the corresponding curves are shown in Figure 20. These relations were critical for simulating the progressive failure mechanisms in RC beams and ensuring reliable prediction of their structural performance under loading.

Figure 20.

Stress–strain relationships for concrete.

The compressive strength for low-strength concrete was determined to be 20 MPa, while for medium-strength concrete, it was 32 MPa. The modulus of elasticity for the low-strength concrete was 19,378.6 MPa, and for the medium-strength concrete, it was 26,587.2 MPa. Additionally, Poisson’s ratio for both concrete types was 0.2.

- Concrete Damage Parameter (CDP)

According to the ABAQUS User’s Manual, tension and compression damage parameters (dt, dc), with values ranging from zero to one, indicate the reduction in concrete stiffness and strength resulting from tensile cracking and compressive crushing [44]. A value of zero indicates no damage, whereas a value of one signifies a complete loss of strength. Various formulas in the literature offer methods for calculating the evolution of damage parameters for concrete under uniaxial compression and stress. The CDP was calculated using Equations (2) and (3).

where

- : Compressive stress in concrete along the descending part of the stress–strain curve.

- : Peak compressive stress in concrete.

- : Tensile stress in concrete along the descending part of the stress–strain curve.

- : Peak tensile stress in concrete.

- Steel reinforcement and NSM-BFRP ropes

The stress–strain relationships of the steel reinforcement were modeled using a linear elastic-perfectly plastic approach. The BFRP ropes were represented as linearly elastic until failure, presuming a perfect bond between the BFRP ropes and the concrete surface via a tie connection. The characteristics of the BFRP ropes and steel reinforcement are detailed in Table 6.

Table 6.

BFRP ropes properties in the elastic stage.

4.2. Validation of Numerical Behavior

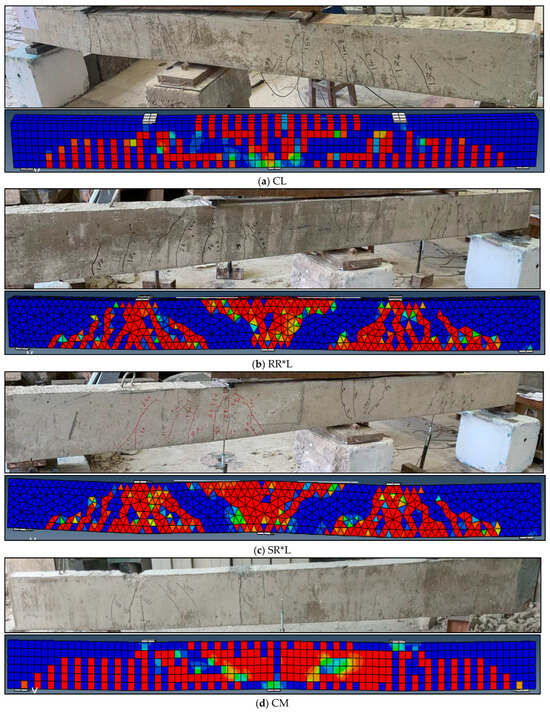

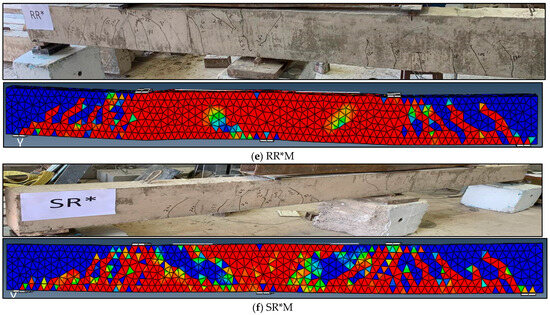

The developed finite element (FE) models were validated using the experimental load–displacement curves and observed crack patterns of the test specimens. Figure 21 shows the numerical and experimental results, while Figure 22 compares the crack patterns. These comparisons indicate a close similarity between the experimental and numerical behaviors of the test specimens. The higher stiffness observed in Figure 21 in the elastic phase of the FE curves compared to the experimental results is primarily due to the idealized material properties and boundary conditions in the FE model. In numerical simulations, concrete is typically assumed to be homogeneous and free from microcracks, whereas real concrete structures contain imperfections, shrinkage effects, and initial microcracks that reduce stiffness. Additionally, the perfect bond assumption between reinforcement and concrete in FE models neglects bond-slip effects, leading to an overestimation of stiffness. Experimental tests also involve instrumentation and support flexibility, which can introduce minor deformations not accounted for in the FE model, further contributing to the observed discrepancy. To evaluate the influence of mesh density on the load–carrying behavior of the beams, a mesh sensitivity analysis was performed. The concrete element size was progressively refined, and the corresponding load–deflection responses and ultimate capacities were compared. The results indicated that further refinement beyond the chosen mesh size produced negligible changes in the predicted ultimate load and failure mode, while substantially increasing computational cost. Therefore, the adopted element size was selected as an optimal balance, ensuring both computational efficiency and accuracy. The selected mesh provided numerical results that agreed well with the experimental load–carrying capacities of the beams. In Figure 22, the tensile stresses in the concrete are depicted using a color gradient: red signifies the highest tensile stresses, yellow indicates lower stresses, and blue represents the lowest tensile stresses. The crack patterns for all test specimens are shown in red. The crack patterns of the beams are positioned below the tensile stress figures. Both negative and positive moment flexural cracks were observed in both the numerical and experimental behaviors of the test specimens, consistent with expectations. It was observed that the cracked regions around the supporting and loading points of the strengthened and rehabilitated beams were more developed than those in the control specimens. This behavior can be explained by the increased load-carrying capacity provided by the BFRP ropes, which allowed the beams to sustain higher loads and consequently caused larger stresses to be concentrated in these critical regions. The redistribution of internal forces in the continuous beams also contributed to the expansion of cracks near the supports and loading points. The presence of BFRP ropes delayed premature failure and enabled the formation of additional flexural cracks, thereby enhancing the ductility and energy absorption capacity of the strengthened and rehabilitated beams. In summary, Figure 21 and Figure 22 demonstrate that the developed FE models effectively predicted the observed behavior of the continuous beams.

Figure 21.

Experimental vs. Numerical load-deflection curves.

Figure 22.

Experimental vs. FEM crack patterns.

Table 3 displays the results from both experimental and numerical analyses. An insignificant difference was observed between the numerical outcomes and the theoretical predictions for the ultimate load, with percentage discrepancies ranging from 0.125% to 7.3%. Significant differences in maximum deflection were observed, ranging from 6.1% to 40%. These variations can be attributed to several factors. For instance, theoretical calculations frequently rely on linear assumptions that may not accurately capture behavior under significant deformations. Moreover, theoretical models often use simplified boundary conditions that may not precisely reflect the real-world load and deflection constraints. Additionally, numerical approximations also play a role in these discrepancies.

4.3. Enhanced Structural Analysis and Configuration Strategies: Utilizing FEM Models and BFRP Ropes

After validation between experimental and FEM results, the work was extended by employing new FEM models, cross-verified against experimental outcomes for congruence. Introducing a configuration featuring two BFRP ropes served as a viable alternative to the use of a single BFRP rope, ensuring identical lengths and placements. Furthermore, supplementary BFRP ropes were incorporated alongside the beam, aligning parallel to the steel reinforcement, complemented by single BFRP ropes situated at the beam’s upper and lower extremities, as depicted in Figure 23a,b. This approach holds promise for advancing predictive capabilities in future applications. Table 7 presents the outcomes of the extended models using FEM, depicting new rehabilitation and strengthening patterns for two-span RC beams. The increase in flexural strength percentage highlights the efficiency of these patterns in comparison to the experimental single rope configuration. Figure 24 shows the crack patterns for the expanded models.

Figure 23.

(a) First pattern; (b) second pattern; Expanded FEM patterns.

Table 7.

Results of expanded models using FEM.

Figure 24.

Expanded FEM configurations crack patterns.

The extended FEM analysis provides a deeper understanding of the structural response of RC beams strengthened with BFRP ropes. By cross-verifying FEM results with experimental data, this study ensures reliability and predictive accuracy, reinforcing the applicability of numerical modeling in structural strengthening and rehabilitation. The incorporation of multiple BFRP ropes, instead of a single one, introduces a more efficient load distribution mechanism, likely improving stress redistribution and crack propagation control.

A key interpretation from the findings is that using two BFRP ropes instead of one results in a more uniform strain distribution, potentially delaying failure and enhancing overall ductility. The additional BFRP ropes placed parallel to the steel reinforcement contribute to stiffness improvements, reducing excessive deflections under loading. Moreover, the strategic placement of BFRP ropes at the upper and lower beam extremities suggests a more balanced approach to flexural strengthening.

The comparison of flexural strength gains between the single and multiple rope configurations highlights the significance of strengthening pattern optimization. As shown in Table 7, the percentage increase in flexural strength confirms the effectiveness of the extended strengthening and rehabilitation techniques. Additionally, the crack patterns in Figure 24 indicate a shift in failure mechanisms, with the enhanced configurations potentially reducing the severity of cracking and increasing the beam’s load-bearing capacity, as the introduction of multiple BFRP ropes in the strengthened and rehabilitated two-span RC beams led to a noticeable shift in failure mechanisms as in beams with a single rope, failure was characterized by premature concrete crushing following the formation of wide flexural cracks, indicating a brittle failure mode. In contrast, beams strengthened or rehabilitated with multiple ropes exhibited delayed crack opening and a more uniform stress distribution. This shifted the failure mechanism from brittle concrete crushing to a more ductile flexural response, where crack propagation and reinforcement yielding preceded the final collapse. The additional ropes increased the tensile capacity of the strengthened region, which reduced stress concentration around cracks and enabled part of the tensile force to be transferred to adjacent zones. This mechanism led to a more uniform distribution of stresses along the beam, delaying local failure and enhancing the flexural performance. As a result, the load-carrying capacity increased by 31–65% for beams with two bottom ropes and by 21.7–58.1% for beams with supplementary side ropes, depending on the beam configuration and concrete strength, as shown in Table 7. The multiple-rope configuration enabled more uniform strain distribution and delayed the onset of critical flexural cracks, reducing stress concentrations and modifying the failure mode from localized brittle flexural cracking to a more distributed flexural-shear failure. This demonstrates that optimizing the placement and number of BFRP ropes, including side ropes, is effective in enhancing both the strength and ductility of continuous RC beams, providing a more resilient structural response.

These insights suggest that refining BFRP rope placement could lead to more resilient and cost-effective structural strengthening strategies. This study’s results emphasize the need for further exploration of alternative strengthening layouts to maximize performance gains while maintaining practical feasibility.

5. Code-Based Results

A theoretical analysis was conducted based on ACI guidelines 440.2R-08 [45] to predict the load-carrying capacity of RC beams reinforced with NSM-BFRP ropes, compressive strength was determined from laboratory cube tests, and yielding strength was obtained from tensile tests on steel reinforcement. Given the limited research on BFRP ropes, Al-Nsour et al. [23] compared GFRP materials with basalt fiber, highlighting their similar manufacturing processes and mechanical properties, and suggesting basalt fiber as a viable alternative. To align with ACI 440.2R-08 guidelines, an environmental reduction factor (CE) of 0.75, akin to GFRP, is proposed for basalt fiber. As shown in Table 3, the theoretical load capacities, compared to the experimental results, exhibit a variation ranging from 4.15% to 17.2%. This discrepancy suggests that ACI 440.2R-08 guidelines tend to provide a higher margin of safety, indicating a cautious and reliable prediction methodology compared to experimental results.

6. Conclusions

Drawing upon experimental, numerical, and code-based findings, the following conclusions can be inferred:

- The use of NSM-BFRP ropes for strengthening and rehabilitating low- and medium-strength RC beams effectively enhances both flexural strength and ductility, enabling higher load capacity and greater deformation before failure without causing concrete cover separation or debonding.

- Strengthened and rehabilitated continuous RC beams demonstrated significant improvements in load-carrying capacity, with increases ranging from 18% to 44% compared to control beams, highlighting the efficacy of proper rope placement in regions experiencing positive and negative moments.

- Numerical simulations using FEM closely replicated experimental behaviors, confirming their reliability as a predictive tool for exploring alternative strengthening configurations, reducing experimental effort, and supporting optimized design strategies.

- The configurations involving two BFRP ropes at the bottom or single-sided ropes with a bottom rope were particularly effective, achieving load enhancements of 31% to 65% and 21% to 58%, respectively, demonstrating the importance of strengthening pattern optimization.

- Comparisons with ACI 440.2R-08 predictions show that the guidelines provide conservative estimates, suggesting that NSM-BFRP strengthening can safely achieve higher performance than standard conservative predictions.

- Overall, this study confirms that NSM-BFRP rope strengthening is a reliable and practical approach for improving the structural resilience, ductility, and load-bearing capacity of RC beams, with clear implications for both design and rehabilitation application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.-J., R.A.-N. and A.A.; methodology, M.A.-J., A.A. and R.A.-N.; validation, M.A.-J. and R.A.-N.; formal analysis, A.A. and; investigation, R.A.-N.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.-N. and A.A.; supervision, M.A.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data of this research were presented in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ferdous, W.; Manalo, A.; Wong, H.S.; Abousnina, R.; AlAjarmeh, O.S.; Zhuge, Y.; Schubel, P. Optimal design for epoxy polymer concrete based on mechanical properties and durability aspects. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 232, 117229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Jaber, M.; Al-Nsour, R.; Shatarat, N.; Hasan, H.; Al-zu’bi, H. Thermal Effect on the Flexural Performance of Lightweight Reinforced Concrete Beams Using Expanded Polystyrene Beads and Pozzolana Aggregate. Eng. Sci 2023, 27, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Jaber, M.; Shatarat, N.; Katkhuda, H.; Al-zu’bi, H.; Al-Nsour, R.; Alhnifat, R.; Al-Qaisia, A. Influence of Temperature on Shear Behavior of Lightweight Reinforced Concrete Beams Using Pozzolana Aggregate and Expanded Polystyrene Beads. CivilEng 2023, 4, 1036–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S.J.; Figueira, R.B. Corrosion Protection Systems and Fatigue Corrosion in Offshore Wind Structures: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Coatings 2017, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, M.; Yaqub, M. Restoration of dynamic characteristics of RC T-beams exposed to fire using post fire curing technique. Eng. Struct. 2021, 249, 113339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saidy, A.H.; Al-Harthy, A.S.; Al-Jabri, K.S.; Abdul-Halim, M.; Al-Shidi, N.M. Structural performance of corroded RC beams repaired with CFRP sheets. Compos. Struct. 2010, 92, 1931–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frappa, G.; Pauletta, M.; Di Marco, C.; Russo, G. Experimental tests for the assessment of residual strength of rc structures after fire—Case study. Eng. Struct. 2022, 252, 113681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frappa, G.; Pauletta, M. Seismic retrofitting of a reinforced concrete building with strongly different stiffness in the main directions. FIB Symp. Proc. 2024, 7, 499–508. [Google Scholar]

- Salh, L. Analysis and Behavior of Structural Concrete Reinforced with Sustainable Materials. Master’s Thesis, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK, 2014. Available online: http://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/id/eprint/16333 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Elsayed, M.; Zhang, L.V.; Nehdi, M.L. Flexural behavior of reinforced concrete T-section beams strengthened by NSM FRP bars. Eng. Struct. 2021, 233, 111922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Jaber, M.T. Influence of externally bonded CFRP on the shear behavior of strengthened and rehabilitated reinforced concrete T-beams containing shear stirrups. Fibers 2021, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.K.H.; Abdel-Jaber, M.S.; Alqam, M. Rehabilitation of Reinforced Concrete Deep Beams Using Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymers (CFRP). Mod. Appl. Sci. 2018, 12, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-zu’bi, H.; Abdel-Jaber, M.; Katkhuda, H. Flexural Strengthening of Reinforced Concrete Beams with Variable Compressive Strength Using Near-Surface Mounted Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Strips [NSM-CFRP]. Fibers 2022, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-khreisat, A.; Abdel-Jaber, M.; Ashteyat, A. Shear Strengthening and Repairing of Reinforced Concrete Deep Beams Damaged by Heat Using NSM–CFRP Ropes. Fibers 2023, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaidat, A.T.; Ashteyat, A.M.; Obaidat, Y.T.; Al-Btoush, A.Y.; Hanandeh, S. Experimental and numerical study of strengthening and repairing heat-damaged RC circular column using hybrid system of CFRP. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rjoub, Y.; Obaidat, A.; Ashteyat, A.; Alshboul, K. Experimental and analytical investigation of using externally bonded, hybrid, fiber-reinforced polymers to repair and strengthen heated, damaged RC beams in flexure. J. Struct. Fire Eng. 2022, 13, 391–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehabat, M.; Ashteyat, A.; Abdel-Jaber, M. Repairing of One-Way Solid Slab Exposed to Thermal Shock Using CFRP: Experimental and Analytical Study. Fibers 2024, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Assih, J.; Li, A. Flexural capacity of continuous reinforced concrete beams strengthened or repaired by CFRP/GFRP sheets. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2021, 104, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.; Al Mahmoud, F.; Khelil, A.; Mercier, J.; Almassri, B. Assessment of the flexural behavior of continuous RC beams strengthened with NSM-FRP bars, experimental and analytical study. Compos. Struct. 2020, 242, 112127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.A.; Akiyama, M.; Kojima, K.; Izumi, N. Flexural behavior of reinforced concrete beams repaired using a hybrid scheme with stainless steel rebars and CFRP sheets. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 363, 129817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshaid, H.; Mishra, R. A green material from rock: Basalt fiber—A review. J. Text. Inst. 2016, 107, 923–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Biswal, K.C. External shear strengthening of RC beams with basalt fiber sheets: An experimental study. Structures 2021, 31, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nsour, R.; Abdel-Jaber, M.; Ashteyat, A.; Shatarat, N. Flexural repairing of heat damaged reinforced concrete beams using NSM-BFRP bars and NSM-CFRP ropes. Compos. Part C Open Access 2023, 12, 100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Park, C.; Moon, D.Y. Characteristics of basalt fiber as a strengthening material for concrete structures. Compos. Part B Eng. 2005, 36, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Tao, J.; Wu, Z. Investigation on the shear behavior of RC beams strengthened with BFRP grids and PCM. Eng. Struct. 2025, 322, 119173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Li, D.; Jin, L.; Du, X. Experimental study on torsional size effect of BFRP bars-RC beams. Eng. Struct. 2025, 326, 119595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Fan, X.C.; Gao, X.; Ge, T. Flexural behavior of BFRP bar–hybrid steel fiber reinforced UHPC beams. Structures 2024, 66, 106838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljidda, O.; Alnahhal, W.; El Refai, A. Flexural strengthening of one-way reinforced concrete slabs using near surface-mounted BFRP bars. Eng. Struct. 2024, 303, 117507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Chen, L.; Su, R.K.L. Seismic behavior of BFRP bar reinforced shear walls strengthened with ultra-high-performance concrete boundary elements. Eng. Struct. 2024, 304, 117697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Xing, G.; Miao, P.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, Z.; Khan, A.Q. Flexural behavior of RC beams strengthened with BFRP bars and CFRP U-jackets: Experimental and numerical analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Jaber, M.; Al-Nsour, R.; Almahameed, A.; Ashteyat, A. Comparative analysis of shear behavior in continuous low-strength RC beams strengthened with BFRP and CFRP: An experimental and numerical investigation. Compos. Part C Open Access 2025, 16, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madotto, R.; Van Engelen, N.C.; Das, S.; Russo, G.; Pauletta, M. Shear and flexural strengthening of RC beams using BFRP fabrics. Eng. Struct. 2021, 229, 111606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saribiyik, A.; Abodan, B.; Balci, M.T. Experimental study on shear strengthening of RC beams with basalt FRP strips using different wrapping methods. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2021, 24, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Jaber, M.; Al-Nsour, R.; Ashteyat, A. Flexural strengthening and rehabilitation of continuous reinforced concrete beams using BFRP sheets: Experimental and analytical techniques. Compos. Part C Open Access 2025, 16, 100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Test, C.C.; Aggregate, C.; Aggregate, F.; Content, A.; Rooms, M.; Concrete, P. Astm C192. Management 2002, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM A615/A615M-12; American Association State Highway and Transportation Officials Standard Standard Specification for Deformed and Plain Carbon-Steel Bars for Concrete Reinforcement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- ACI Committee. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary (ACI 318M-11); ACI Committee: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Zhang, A.; Guo, Y. Effect of preload level on flexural load-carrying capacity of RC beams strengthened by externally bonded FRP sheets. Open Civ. Eng. J. 2015, 9, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.H.; Jin, W.L.; Li, G.B. Behavior of preloaded RC beams strengthened with CFRP laminates. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2016, 7, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduini, M.; Di Tommaso, A.; Nanni, A. Brittle failure in FRP plate and sheet bonded beams. ACI Struct. J. 1997, 94, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajaddini, M. Investigation of moment redistribution in FRP strengthened continuous RC members. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bath, Bath, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- El Refai, A.; Abed, F.; Al-Rahmani, A. Structural performance and serviceability of hybrid GFRP-steel reinforced concrete continuous beams. Compos. Struct. 2020, 240, 111998. [Google Scholar]

- Spadea, G.; Bencardino, F.; Swamy, R.N. Structural behavior of composite RC beams with externally bonded CFRP. J. Compos. Constr. 1998, 2, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassault Systèmes Simulia. Abaqus 6.12 analysis user’s manual: Prescribed conditions, constraints & interactions. Abaqus 2012, 5, 831. [Google Scholar]

- Soudki, K.; Alkhrdaji, T. Guide for the Design and Construction of Externally Bonded FRP Systems for Strengthening Concrete Structures (ACI 440.2R-02); American Concrete Institute: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).