1. Introduction

Water-based drilling fluids (WBDFs) represent the most widely used and environmentally preferred option in oil and gas well drilling operations, owing to their lower cost and reduced ecological impact compared to oil-based or synthetic drilling fluids [

1,

2,

3]. However, these fluids pose major operational challenges, primarily related to wellbore instability caused by the hydration and swelling of clay-rich shale formations. Such phenomena often lead to serious complications, including pipe sticking, increased drag and torque, wellbore erosion, formation collapse, gelation, circulation loss, shale swelling, and overall wellbore instability [

4,

5]. This detrimental behavior arises from the expansion of clay particles upon contact with water, which weakens the structural integrity of the shale and adversely affects drilling efficiency and hydrocarbon recovery [

6,

7]. Consequently, recent research efforts have increasingly focused on developing efficient shale inhibitors to mitigate swelling and improve the rheological performance of WBDFs. In this context, nanoparticles have emerged as a promising class of drilling fluid additives owing to their high specific surface area and ability to regulate clay water interactions through precise physico-chemical mechanisms, thereby enhancing wellbore stability and drilling performance under complex geological conditions [

8]. Shale formations are typically characterized by laminated structures, micro-fractures, and nano- to micro-sized pores. The intrusion of water into these formations accelerates shale swelling, weakens inter-particle bonding, and significantly increases the risk of wellbore instability [

9]. Accordingly, the effective sealing of nanoporous shale matrices and micro-fractures has become a critical strategy for maintaining wellbore integrity, where nanoparticles, owing to their ultra-small size, large surface area, and compatibility with shale pore dimensions, function as efficient nano-plugging agents within WBDF systems [

8,

10].

Several studies have demonstrated the potential of metal oxide nanoparticles to enhance the rheological, filtration, and shale inhibition performance of water-based drilling fluids (WBDFs). Bin Irfan and Busahmin [

11] reported that Fe

2O

3 nanoparticles reduced fluid loss from 12.0 mL/30 min to approximately 5.2 mL/30 min while increasing shale recovery to about 85%, whereas Fe

3O

4 exhibited strong nanopore-sealing capability with a plastic viscosity of around 27 cP under HPHT conditions. Similarly, Vryzas et al. [

12] showed that custom-made Fe

3O

4 nanoparticles (6–8 nm) synthesized via co-precipitation reduced fluid loss by ≈40% (from 17.5 to 10.5 mL) and increased yield stress to 7.55 Pa at 60 °C, outperforming commercial Fe

3O

4. Hybrid and oxide-based systems have also been explored; Anwar Ahmed et al. [

13] achieved an ≈87% reduction in PPT fluid loss using SiO

2/g-C

3N

4 nanocomposites, accompanied by a yield point increase to 46 lb/100 ft

2 after aging, while Bayat and Shams [

4] reported improvements in plastic viscosity, gel strength, shale recovery (up to 49%), and mud-cake permeability (0.82 mD) using commercial SiO

2, ZnO, and TiO

2 nanoparticles.

Further investigations highlighted the role of surface chemistry and particle–clay interactions. Pourkhalil and Nakhaee [

14] demonstrated that positively charged ZnO nanoparticles (≈19 nm) reduced pore pressure transmission by 60–96% through electrostatic adsorption, whereas Dejtaradon et al. [

15] observed a ≈30% fluid-loss reduction and a 27.6% decrease in mud-cake thickness with 0.8 wt % CuO nanoparticles. In contrast, Alsaba et al. [

16] reported that although CuO achieved high shale swelling reduction (≈83%), MgO increased filtrate loss by ≈116% under their testing conditions. Collectively, these studies indicate that metal oxide nanoparticles can significantly influence WBDF performance; however, the reported outcomes remain highly system-dependent, often focusing on single oxides, different synthesis routes, and non-comparable formulations, thereby limiting direct structure–property–performance correlations.

Based on the above considerations, the present study was designed to test the hypothesis that nanocrystalline metal oxides with distinct crystal structures, surface chemistries, and aggregation behaviors when synthesized via the same chemical route would exhibit fundamentally different shale inhibition mechanisms and drilling fluid performances in water-based drilling fluids (WBDFs). Unlike most previous studies that focus on a single nanoparticle system or report performance improvements without mechanistic correlation, this work provides a systematic and comparative evaluation of ZnO, Fe

2O

3, MgO, and CuO nanocrystalline oxides prepared under identical conditions and incorporated into the same WBDF formulation. By integrating structural (XRD), morphological (SEM), colloidal (DLS), textural (BET), and thermal (TGA–DTG) characterizations with rheological, filtration, and dynamic linear swelling measurements, this study establishes direct structure–property–performance relationships governing shale inhibition. Furthermore, the inhibition efficiency of the nanocrystalline oxide-based systems is benchmarked against commercial inhibitors (Amine NF and Glycol) previously evaluated under identical experimental protocols [

17], allowing an objective assessment of their relative effectiveness and sustainability potential. This comprehensive framework distinguishes the present results from the existing literature and highlights the viability of inorganic metal oxides particularly MgO and Fe

2O

3 as thermally robust and environmentally benign alternatives for advanced WBDF formulations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O, VWR Chemicals, Avantor, Radnor, PA, USA, ≥98%), Zinc Chloride (ZnCl2, Chimreactiv S.R.L, Bucharest, Romania, ≥98%), Magnesium chloride hexahydrate (MgCl2·6H2O, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany, ≥99.0%), Copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate, (CuSO4·5H2O, Merck, ≥99.9%), Potassium hydroxide (KOH, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, 99.98%).

Additional commercial additives, including defoamer (anti-foaming agent), bactericide, amine NF, and glycol (commonly applied as anti-hydrate agents), were supplied by Newpark Romania (Ploiești, Romania). Barite (BaSO4, weighting material) was obtained from RUA Bulgaria (Sofia, Bulgaria). All chemicals were of analytical grade.

2.2. Synthesis of the Nanocrystalline Oxides

Nanoparticles of zinc oxide (ZnO), iron oxide (Fe

2O

3), magnesium oxide (MgO), and copper oxide (CuO) were synthesized via the co-precipitation method [

18,

19] using their respective metal salts: ZnCl

2, FeCl

3·6H

2O, MgCl

2·6H

2O, and CuSO

4·5H

2O. Specifically, 70 g of each precursor salt was dissolved in 1000 mL of deionized water within a flat-bottom three-neck flask. The pH of the solution was initially adjusted to 3.0 using 36% hydrochloric acid to ensure complete dissolution. The mixture was maintained at 60 °C under continuous magnetic stirring at 1000 rpm, while a steady flow of nitrogen gas was continuously bubbled through the solution throughout the entire synthesis to maintain an inert atmosphere. Furthermore, a 5 N potassium hydroxide solution was added dropwise until the pH reached 9–10, which led to the formation of metal hydroxide precipitates. As pH control is critical at this stage for nucleation and phase selectivity, the pH was monitored during the precipitation step by using a calibrated pH meter and pH indicator paper. The suspension was stirred for an additional 45 min to allow complete nucleation and particle growth. Subsequently, the nanocrystalline oxide products were separated by centrifugation, washed repeatedly with deionized water in order to remove residual salts, followed by ethanol, and then dried at 150° for 2 h. Finally, the dried powders were calcined at 400 °C for 4 h with a heating rate of 10 °C min

−1 to obtain the corresponding nanocrystalline metal oxides.

The co-precipitation route employed in this study is widely recognized in the literature as a simple, efficient, and reproducible method for the synthesis of nanocrystalline metal oxides, offering high phase selectivity under mild conditions [

18,

19,

20]. Although each oxide system was synthesized in a single batch, the absence of secondary phases and the excellent crystallinity confirmed by XRD indicate an efficient conversion of the precursor salts into the corresponding oxides. Minor material losses may occur during centrifugation, washing, and drying steps; however, these losses are associated with physical handling rather than incomplete chemical reactions. The synthesis by-products primarily consist of soluble potassium and chloride ions formed during precipitation, which were effectively removed through repeated washing with deionized water and ethanol. Therefore, the primary objectives of this work were controlled nanocrystalline oxide synthesis and phase purity rather than quantitative yield determination.

2.3. Preparation of Water-Based Drilling Fluids

Four formulations of water-based drilling muds (WBMs) were prepared following the compositions presented in

Table 1. The preparation procedure was carried out following the same sequence of steps and operational conditions described in our previously published work [

17], which ensured consistency in the mixing order and processing parameters.

For the base fluid, 929 mL of tap water was initially mixed for 1 min with 0.3 g of sodium hydroxide to increase the alkalinity. Subsequently, 0.5 g of sodium carbonate was added and stirred for another 1 min, followed by the incorporation of 70 g of potassium chloride, which was mixed for 2 min to ensure complete dissolution. Thereafter, 1 mL of defoamer and 1 mL of bactericide were successively added, each mixed for 1 min under continuous agitation.

According to the specified formulations, either commercial shale inhibitors (Amine NF, Glycol) or the synthesized nanocrystalline metal oxides were incorporated as detailed in

Table 1, with each additive blended for an additional 2 min. For fluid-loss control, 3 g of xanthan gum was added and mixed for 5 min, while 10 g of PAC-LV was used for rheological adjustment and similarly mixed for 5 min. Finally, 203 g of barite was introduced as the weighting material to achieve the target mud density, followed by a 42 min mixing step to ensure full homogenization.

All mud formulations were prepared at room temperature using a Hamilton Beach mixer (Hamilton Beach, Glen Allen, VA, USA, 50 min, speed setting 2). The mixtures were then subjected to high-shear homogenization with a Silverson mixer (Silverson, East Longmeadow, MA, USA) operating at 6000 rpm for 10 min to promote uniform dispersion of all solid and liquid constituents.

After preparation and preliminary testing, four selected formulations were evaluated for shale inhibition efficiency using a Dynamic Linear Swell Meter (OFITE, Houston, TX, USA) over a period of 70 h. Shale wafers were fabricated from 15 g of shale cuttings (<500 μm) collected from the X Rosetti formation (depth 2917 m), whose mineralogical composition was previously characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) in our earlier work [

17]. The cuttings were compacted at 6000 psi (~41 MPa) for 30 min in a cell press, yielding wafers with a molded density of 2.6 g/cm

3 and a diameter of 28 mm. Prior to testing, the wafers were conditioned for 24 h under controlled ambient conditions.

Swelling measurements were conducted at a temperature range of 20–23 °C, and the swelling inhibition efficiency of each formulation was compared to determine the relative performance of the nanocrystalline oxide-based systems against commercial benchmark inhibitors.

2.4. Characterization of the Nanoparticles

The synthesized nanocrystalline metal oxides were comprehensively characterized using a range of analytical techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), textural analysis (N2 adsorption/desorption), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA–DTG), and dynamic light scattering (DLS).

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed using a D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker-AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) [

21]. The instrument, configured in a θ–θ geometry with a Bragg–Brentano optical setup, recorded diffraction patterns within the 2θ range of 5–60° under the following operating parameters: tube voltage of 40 kV, anode current of 40 mA, a step size of 0.1° (2θ), and a scanning speed of 0.1° per 5 s. Data acquisition was performed using XRD Commander v2.6.1, qualitative phase identification was carried out with Diffracplus EVA v14 software in conjunction with the PDF-ICDD database, and quantitative phase analysis was performed using Diffracplus TOPAS v4.1.

The microstructural morphology was examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) from FEI Company (Hillsboro, OR, USA) which provided detailed surface imaging [

19].

Thermogravimetric (TGA) and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) analyses were carried out on a METTLER TOLEDO TGA/IST Thermal Analysis System (Greifensee, Switzerland) [

22] in the 30–550 °C temperature range under a nitrogen atmosphere, with a constant heating rate of 10 °C min

−1. These analyses were used to evaluate the thermal stability and decomposition behavior of the nanocrystalline oxides.

Textural properties of the samples were determined by using a Quantachrome NOVA 2200 e Gas Sorption Analyzer (Boynton Beach, FL, USA). Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured at 77.35 K over a relative pressure range (p/p0 = 0.005–1.0). Data processing was performed using NovaWin software, version 11.03. The specific surface area was calculated by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method, whereas the total pore volume was estimated from the desorbed nitrogen volume at a relative pressure close to unity, applying the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) approach.

Particle size and size distribution of the oxide dispersions were measured using a Zetasizer Nano ZS—Red Badge system (Malvern, Worcestershire, UK) based on the Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) technique. The instrument was calibrated for particle sizes ranging from 0.6 nm to 6 µm. This method correlates the particle size with the rate of Brownian motion, and the relationship between particle size and its diffusion rate is defined by the Stokes–Einstein equation [

23,

24].

The combined results obtained from these complementary techniques provided a comprehensive understanding of the crystalline structure, surface texture, morphology, and colloidal stability of the synthesized nanocrystalline metal oxides, establishing their suitability for application as shale inhibitors in water-based drilling fluids.

2.5. Characterization and Testing of Nanoparticle-Modified Water-Based Drilling Fluids

The alkalinity of the drilling fluids was determined to quantify the concentrations of bicarbonate (HCO

3−), carbonate (CO

32−), and hydroxyl (OH

−) ions in accordance with API Recommended Practice 13B. The titration procedure employed 0.02 N sulfuric acid as the titrant, with phenolphthalein and bromocresol green serving as pH indicators. The calcium and magnesium ion contents, which define the total hardness of the drilling fluid, were also measured following the API RP 13B-1 protocol [

25]. Standard complexometric titration was performed using standardized disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate dihydrate (EDTA) as the chelating agent, along with a buffer solution of ammonium chloride and ammonium hydroxide, and calmagite (Calver II) as the colorimetric indicator [

25]. The experimental procedures for the chemical characterization and testing of the drilling fluids were conducted following the same methodology and analytical sequence established in our previous work [

17], ensuring methodological consistency and reproducibility.

The chloride ion concentration (Cl

−) in the filtrate was quantified through argentometric titration, utilizing 1 N silver nitrate as the titrant and potassium chromate as the endpoint indicator. The pH of the titration system was adjusted using 0.02 N sulfuric acid and phenolphthalein, in full compliance with API RP 13B-1 [

25]. All titrations were performed on filtrate samples collected from the drilling fluids at ambient temperature.

In addition to spectroscopic and thermal characterizations, the physicochemical and rheological behaviors of the synthesized water-based drilling fluids (WBMs) were systematically assessed. Measurements included mud weight (g/cm3) for density determination and pH to evaluate the degree of acidity or alkalinity. The rheological profiles were characterized using a Fann viscometer operated at 49 °C, with dial readings taken at 600, 300, 200, 100, 6, and 3 rpm. The gel strengths after 10 s and 10 min (Gels 10″/10′) were determined to describe thixotropic recovery behavior. Based on these data, both plastic viscosity (PV) and yield point (YP) values were calculated to define the fluid’s flow characteristics and suspension capacity.

Filtration performance was examined according to the API standard filtrate volume (mL), while the mud cake thickness (mm) was measured to assess the buildup of the filter cake on the porous medium. The lubricity coefficient was also determined to estimate the friction-reducing capability of the drilling fluid.

The anti-swelling efficiency of the nanocrystalline metal oxides, namely ZnO, Fe

2O

3, MgO, and CuO, was evaluated through linear swelling tests using a Dynamic Linear Swell Meter (OFITE) equipped with a compactor and computer interface. This apparatus provides a simple, low-cost, and widely recognized laboratory method for assessing the shale hydration inhibition efficiency of water-based drilling fluid additives [

7,

16].

The ionic composition of the filtrates was analyzed to further understand how the synthesized nanocrystalline oxide additives influenced the aqueous chemistry of the WBMs. Standard analytical procedures were employed to determine Ca2+, Mg2+, and Cl− ions, as well as HCO3−, CO32−, and OH− species. Monitoring these parameters is crucial, as ionic equilibria play a decisive role in controlling shale hydration, dispersion, and overall fluid stability.

Finally, to achieve a comprehensive performance evaluation, the inhibition capabilities of the synthesized nanocrystalline metal oxides (ZnO, Fe2O3, MgO, and CuO) were systematically compared with those of the commercial benchmark inhibitors Amine NF and Glycol which are widely utilized in conventional water-based drilling fluid systems.

2.6. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis of the Nanoparticles

The XRD patterns (

Figure 1) confirm the successful formation of phase-pure nanocrystalline metal oxides for all four investigated systems. The pattern of ZnO exhibits the characteristic reflections of the hexagonal wurtzite structure (P6

3mc) at 2θ ≈ 31.8° (100), 34.4° (002), 36.3° (101), 47.6° (102), and 56.6° (110) [

4,

26,

27,

28], which are well indexed to the JCPDS card no. 80-0075 corresponding to the lattice planes of wurtzite symmetry with a hexagonal unit-cell structure [

29]. The dominance of the (101)/(002) doublet and the absence of any impurity peaks indicate high phase purity and excellent crystallinity. The observed peak broadening relative to bulk ZnO standards reflects the nanocrystalline nature of the sample [

30,

31].

The MgO pattern (

Figure 1) corresponds to the cubic periclase structure (Fm–3m), with well-defined reflections at ~30.6° (220), 37.8° (222), 40.7° (111), and 42.9° (400). The intense line near 42.9° is assigned to the (400) reflection [

32,

33]. The moderate peak broadening again suggests coherently diffracting domains within the nanometre scale. The JCPDS NO: 01–076-1363 was used to identify the 200 peak locations.

For iron(III) oxide (Fe

2O

3), the diffraction pattern (

Figure 1) matches that of the hematite phase (α-Fe

2O

3, R–3c), with prominent peaks at ~24.5° (012), 33.2° (104), 35.7° (110), and 54.1° (116), which is well matched with JCPDS Card No 33-0664 [

34,

35,

36,

37]. The absence of spinel-type reflections verifies the formation of a single-phase hematite structure. The relatively broad (104)/(110) peaks are indicative of fine crystallites and/or lattice microstrain features typically associated with nanocrystalline oxides synthesized by wet-chemical routes [

37].

The CuO pattern (

Figure 1) displays the characteristic reflections of the monoclinic tenorite structure (C2/c) at ~32.8° (110), 35.8° (−111), 49.0° (−202), and 58.8° (202), which is good agreement with JCPDS card number 45-0937 [

34,

38,

39]. No reflections corresponding to cuprous oxide (Cu

2O) are detected within the scanned range, confirming complete oxidation and excellent phase selectivity. The noticeable broadening of the (110)/(111) peaks further supports the nanocrystalline character of the CuO sample [

40].

Overall, the four diffraction profiles exhibit: (i) peak positions and relative intensities in excellent agreement with the JCPDS standards for ZnO (zincite), MgO (periclase), Fe2O3 (hematite), and CuO (tenorite); (ii) the absence of secondary phases or unreacted precursors; and (iii) significant peak broadening consistent with nanoscale crystallite domains.

The average crystallite size (D) of the nanoparticles was calculated using the Debye–Scherrer Equation (1) [

22,

41],

where λ = 0.15406 nm (Cu Kα radiation), k = 0.98 (shape factor), β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak, and θ is the Bragg angle. The resulting values, summarized in

Table 2, indicate average crystallite sizes of approximately 37 nm for ZnO (zincite) with individual peaks ranging 29–44 nm, 28 nm for MgO (periclase) (27–31 nm), 38 nm for α-Fe

2O

3 (hematite) (32–50 nm), and 17.0 nm for CuO (tenorite) (11–28 nm).

The narrower peaks of α-Fe2O3 at (110) (2θ ≈ 35.7°) yielded the largest single-domain size (~50 nm), while the broader reflections of CuO (e.g., (−111) at 35.8°) correspond to the smallest (~11–12 nm), thus confirming its pronounced nanocrystallinity. For ZnO, the variation in peak widths between the (101)/(002) and higher-angle reflections (e.g., (102), (110)) suggests moderate crystallographic anisotropy and/or microstrain behavior also noted, though less prominent, in MgO.

In summary, the XRD-derived metrics confirm the nanocrystalline and single-phase nature of all synthesized oxides. Among them, CuO exhibits the finest coherent domains, followed by MgO ≈ ZnO, while α-Fe2O3 displays slightly larger crystallites. These results are fully consistent with the observed peak broadening in the diffraction patterns and validate the efficiency of the co-precipitation method in producing phase-pure, highly crystalline metal oxide nanoparticles.

2.7. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

The particle size distribution profiles obtained by DLS (

Figure 2) reveal that all synthesized nanocrystalline metal oxides exhibit well-defined intensity peaks, confirming their stable colloidal dispersion in aqueous medium. The measured Z-average hydrodynamic diameters were 633.9 ± 6 nm for ZnO, 1437.7 ± 15 nm for MgO, 891.8 ± 62 nm for α-Fe

2O

3, and 1261.7 ± 8 nm for CuO. These values correspond to the average hydrodynamic diameters, which generally exceed the crystallite sizes derived from XRD due to the presence of solvation layers and varying degrees of secondary aggregation of primary particles in suspension. In dynamic light scattering measurements, the apparent hydrodynamic size is typically larger because DLS detects the hydrated particle including the surrounding solvation shell, adsorbed surface layers, and weakly associated aggregates rather than the dry crystalline core [

42,

43,

44].

The ZnO nanocrystalline displayed the smallest hydrodynamic diameter (≈634 nm) and a relatively narrow distribution (PDI = 0.402 ± 0.065), indicating good dispersion stability and limited particle agglomeration. The MgO system showed the highest Z-average (≈1438 nm) with a PDI of 0.444 ± 0.024, suggesting the coexistence of small clusters and larger aggregates, a behavior commonly attributed to the high surface energy and electrostatic interactions among Mg2+-terminated surfaces.

For α-Fe2O3, the average hydrodynamic diameter of ≈ 892 nm and a PDI = 0.561 ± 0.013 reflect a broader size distribution, which can be associated with partial agglomeration of hematite crystallites produced by wet-chemical synthesis. In contrast, the CuO nanocrystalline oxide system exhibited a Z-average of 1261.7 ± 8 nm with the lowest PDI among the four samples (0.357 ± 0.037), indicating a relatively uniform colloidal dispersion with stable hydrodynamic behavior.

Overall, all samples presented PDI values below 0.6, which denotes moderate to good monodispersity and confirms the suitability of the co-precipitation route for producing stable colloidal nanocrystalline metal oxides. The DLS results are consistent with the XRD analyses, as both techniques confirm nanocrystalline primary domains that assemble into larger secondary aggregates in aqueous suspension, rather than reflecting isolated primary particle size.

From a performance perspective, the relatively large hydrodynamic sizes measured by DLS (≈600–1400 nm) reflect controlled secondary aggregation rather than poor dispersion. Such aggregation plays a functional role in water-based drilling fluids by enhancing nanoplugging efficiency, where sub-micrometric and micrometric clusters effectively bridge shale nanopores and microfractures [

10,

45]. This behavior contributes to reduced filtrate loss and improved swelling inhibition, particularly for MgO- and Fe

2O

3-based systems. At the same time, differences in aggregation degree, reflected by Z-average and PDI values, influence colloidal stability and rheological response [

10,

45]. Therefore, the observed agglomeration represents a balance between enhanced sealing performance and acceptable dispersion stability, rather than a limitation of the nanoparticle systems.

2.8. Morphological Characterization by SEM

The SEM micrographs (

Figure 3) reveal morphology consistent with phase-pure, nanocrystalline oxides evidenced by XRD. ZnO appears as crumpled nanosheets/plate-like aggregates forming flower-like clusters. Such lamellar textures are typical of zincite ZnO [

46,

47] and explain the pronounced (002)/(101) reflections in XRD. The aggregates comprise primary nanoscale crystallites (XRD D = 36.76 nm) that assemble into sub-micrometric structures, yielding a Z-average ≈ 634 nm with moderate polydispersity (PDI ≈ 0.40) in DLS, i.e., hydrodynamic entities larger than crystallites due to solvation shells and loose clustering.

Direct SEM measurements further indicate lateral aggregate dimensions in the range of approximately 600–760 nm (

Figure 3), confirming that the observed ZnO entities correspond to secondary assemblies of nanoscale crystallites rather than individual particles.

MgO shows rough, granular surfaces interspersed with plate-like fragments, indicative of periclase nanocrystallites that coalesce into compact secondary aggregates [

48,

49].

SEM analysis directly reveals strongly agglomerated granular structures with secondary particle sizes ranging from approximately 0.6 to 1.9 µm, confirming the formation of large clusters from nanoscale primary crystallites. This pronounced aggregation behavior is consistent with the largest hydrodynamic diameter measured by DLS (Z-average ≈ 1.44 µm; PDI ≈ 0.44), while XRD indicates much smaller coherent domains (D ≈ 28.5 nm).

Accordingly, SEM provides the missing morphological link between XRD and DLS, demonstrating that the apparent size discrepancy arises from multi-crystallite aggregates formed due to the high surface energy of MgO during drying and dispersion, rather than from the growth of individual crystallites [

50].

For α-Fe

2O

3 (hematite), SEM shows densely packed, near-spherical nanocrystalline oxide aggregates forming uniform carpets [

51].

Measured particle dimensions fall predominantly within the ~160–300 nm range, in agreement with the nanocrystalline sizes from XRD (D ≈ 38.2 nm). However, broader intensity envelopes in DLS (Z-average ≈ 892 nm; PDI ≈ 0.56) indicate a wider distribution driven by partial agglomeration of primary grains consistent with the relatively broader (104)/(110) XRD peaks that also hint at microstrain [

52,

53].

CuO (tenorite) presents as soft agglomerates of very fine primary particles, matching the smallest XRD crystallite size (D ≈ 17.0 nm).

SEM-derived particle sizes are mainly in the ~100–180 nm range, confirming the nanoscale nature of the primary CuO particles. Despite forming micron-scale clusters, the distributions are comparatively narrower (Z-average ≈ 1260 nm; PDI ≈ 0.36), suggesting more uniform secondary structures than MgO [

54] and α-Fe

2O

3, consistent with the pronounced but consistent broadening of (110)/(111) reflections in XRD.

Taken together, these results clarify the apparent size discrepancy between XRD, SEM, and DLS measurements. XRD captures the size of the primary nanocrystalline domains (17–38 nm), SEM directly visualizes their assembly into sub-micrometric or micrometric secondary aggregates, and DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter of these aggregates in suspension [

55,

56]. Therefore, the classification of the synthesized oxides as nanomaterials is based on the size of their primary crystalline domains and intrinsic nanoscale features, rather than on the dimensions of secondary aggregates [

57]. Such hierarchical aggregation behavior is well documented for metal oxide nanomaterials synthesized by wet-chemical routes and arises from high surface energy and interparticle interactions [

58]. Importantly, the presence of secondary aggregates does not contradict their classification as nanomaterials, as their crystallinity, surface chemistry, and functional properties remain governed by nanoscale primary domains.

SEM observations provide direct evidence of the hierarchical organization of the synthesized metal oxide particles, consisting of nanoscale primary crystallites assembled into submicron or micron-sized secondary aggregates. In this context, the crystallite sizes estimated from XRD using the Scherrer equation should be regarded as apparent coherent domain sizes, which may underestimate the real mean crystallite dimensions by a factor of approximately 2–3, since instrumental broadening and microstrain contributions to the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peaks were not considered. Consequently, the grain sizes observed by SEM are more representative of the actual mean crystallite dimensions. From a classification perspective, crystallite or grain sizes in the range of approximately 100–300 nm are still conventionally considered within the nanomaterial domain, owing to the distinctive surface-related and physicochemical properties exhibited by powders in this size regime, despite their proximity to the submicrometer scale.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements, on the other hand, report hydrodynamic diameters in the 600–1450 nm range, as they probe solvated, secondary aggregates dispersed in aqueous media. SEM directly visualizes these secondary structures, thereby reconciling the apparent discrepancy between XRD and DLS results. Overall, the particle size trend from the smallest XRD-derived crystallite dimensions to the largest DLS-measured hydrodynamic diameters follows the order: CuO < ZnO < Fe2O3 < MgO, reflecting increasing degrees of aggregation.

2.9. BET Isotherm Analysis

The N

2 adsorption–desorption isotherms (

Figure 4) and the derived textural parameters (

Table 3) indicate predominantly mesoporous architectures (modal pore widths ≈ 21–56 nm), which arise from interparticle voids within aggregated assemblies of nanocrystalline oxides rather than from intrinsic porosity of individual particles. The sharp uptake at high relative pressure (P/P

0 → 1) is consistent with capillary condensation between densely packed nanocrystalline domains in aggregated powders.

Due to the very low porosity and the absence of significant capillary condensation, a reliable mean pore size could not be determined for Fe2O3 and ZnO powders. Accordingly, quantitative BET/BJH parameters are reported only where meaningful, as follows: MgO (specific surface area 17.93 m2 g−1; pore volume 0.111 cm3 g−1; modal pore width ≈ 21.4 nm) and CuO (20.47 m2 g−1; pore volume 0.223 cm3 g−1; modal pore width ≈ 50.7 nm), while ZnO (2.33 m2 g−1) and α-Fe2O3 (4.30 m2 g−1) are characterized by very low surface areas and lack well-defined mesoporosity.

CuO exhibits the highest surface area and largest pore volume, pointing to open, loosely packed aggregates built from very fine primary crystallites fully coherent with XRD (smallest D ≈ 17 nm) and SEM (cauliflower-like agglomerates of nanoscale grains). This hierarchical porosity explains its comparatively narrow DLS dispersity (PDI ≈ 0.36) despite micron-scale hydrodynamic sizes and suggests abundant adsorption/anchoring sites for interaction with clay platelets.

MgO shows intermediate surface area (≈18 m2 g−1) and a mesopore mode around 21 nm, consistent with SEM granules interspersed with plate-like fragments (periclase) forming compact secondary aggregates. Although the textural surface is appreciable, DLS reports the largest Z-average (≈1438 nm), reflecting strong interparticle attraction and multi-crystallite clustering, an observation that reconciles the relatively small XRD crystallites (D ≈ 28.5 nm) with the large hydrodynamic entities measured in suspension.

For α-Fe2O3, the low surface area (≈4.3 m2 g−1) indicates dense packing of near-spherical grains, as seen by SEM. The broader DLS envelope (PDI ≈ 0.56) and the relatively broadened XRD (104)/(110) reflections are consistent with partial agglomeration and microstrain, which reduce accessible surface while producing interparticle mesopores near the BJH mode (~50 nm).

ZnO presents the lowest surface area (≈2.33 m2 g−1), in line with SEM crumpled nanosheets forming flower-like stacks that collapse into slit-like voids at high P/P0. Although XRD confirms well-crystallized zincite domains (D ≈ 36.8 nm), the tight lamellar stacking limits accessible external area, which explains the modest BET values and the moderate DLS size (Z-average ≈ 634 nm).

Overall, the BET/BJH parameters summarized in

Table 3 corroborate the SEM and XRD results, confirming that the textural properties are governed by the aggregation state of nanocrystalline domains rather than by isolated nanoparticles, thereby ensuring full structural–textural consistency across the characterization techniques.

2.10. TGA–DTG Analysis

The thermogravimetric (TGA) and differential thermogravimetric (DTG) profiles of the synthesized nanocrystalline metal oxides are shown in

Figure 5, and illustrate the weight loss and corresponding decomposition rates within the temperature range of 30–600 °C.

For ZnO nanocrystalline oxide, the TGA curve displays three distinct weight-loss regions: an initial 3.4% loss below 180 °C due to desorption of physically adsorbed water, followed by a 6.7% reduction around 260 °C attributed to the removal of residual hydroxyl groups from the precursor [

59,

60]. The major loss of 22.4% up to 550 °C corresponds to structural densification and partial dehydroxylation of surface sites.

In the case of MgO, the sample shows a 6.7% loss below 160 °C, mainly from adsorbed moisture, and a subsequent 7.1% event near 200 °C related to decomposition of surface hydroxides [

61,

62]. A gradual 25.5% decline up to 550 °C corresponds to the transition of residual Mg(OH)

2 to MgO. The broad DTG peak indicates a progressive dehydration process, consistent with SEM observations of rough, porous surfaces and moderate BET surface area, both favoring surface adsorption phenomena.

The α-Fe2O3 nanocrystalline oxide exhibits remarkable thermal stability, with a total mass loss below 1.5% up to 550 °C. Minor losses of 0.5%, 0.7%, and 1.1% at 175, 300, and 500 °C, respectively, are attributed to the release of adsorbed moisture and trace volatile impurities. The absence of pronounced DTG peaks confirms the high crystallinity and purity of the hematite phase detected by XRD, as well as the dense, low-surface-area morphology revealed by BET (4.3 m2 g−1).

The CuO nanoparticles show three degradation stages: an initial 2.4% loss at 200 °C (desorption of weakly bound water), followed by a 4.6% loss at 350 °C associated with dehydroxylation of Cu(OH)

2 residues [

63], and a final 9.5% loss up to 550 °C related to lattice rearrangement and removal of trapped oxygen species [

64]. The pronounced DTG peaks indicate localized structural reorganization typical of nanoscale tenorite. The overall thermal behavior suggests higher reactivity of CuO compared to other oxides, correlating with its fine crystallite size (≈17 nm, XRD) and high specific surface area (≈20 m

2 g

−1, BET).

Overall, all four nanocrystalline metal oxides display excellent thermal stability up to 500 °C, confirming their suitability as thermally robust nano-additives for water-based drilling fluids (WBDFs). The relative order of stability follows the sequence: α-Fe2O3 > ZnO > MgO > CuO, which is inversely related to their surface area and degree of nanostructural porosity observed in BET and SEM analyses.

3. Performance Evaluation of Nanocrystalline Metal Oxides-Based WBDFs

The rheological, filtration, and inhibition behaviors of the water-based drilling fluids (WBDFs) containing the synthesized nanocrystalline metal oxides (Fe

2O

3, CuO, ZnO, and MgO) were systematically evaluated, and the results are summarized in

Table 4 and

Figure 6. All formulations exhibited mud densities (1.20 g/cm

3) and maintained stable flow properties at 49 °C, thus confirming good dispersion of the nanocrystalline oxide aggregates and compatibility with the base fluid matrix. The addition of nanocrystalline oxides slightly modified the plastic viscosity (PV) and yield point (YP), which remained within the optimal operational range. The lowest PV (17 mPa·s) was recorded for MgO, followed by ZnO (18 mPa·s), while Fe

2O

3 and CuO both maintained 19 mPa·s. This indicates that MgO and ZnO nanocrystalline oxides enhanced fluid mobility and reduced internal friction between clay platelets, although through different morphological mechanisms rather than similar surface structures. The MgO nanocrystalline oxide, exhibiting rough granular surfaces interspersed with plate-like fragments as revealed by SEM, forms compact secondary aggregates that facilitate smoother flow and stable suspension, consistent with their moderate BET surface area (17.93 m

2 g

−1) and high hydrodynamic diameter (Z-avg ≈ 1438 nm). In contrast, ZnO nanocrystalline oxide, consisting of crumpled nanosheets and plate-like clusters typical of zincite ZnO, likely orient under shear to create layered slip planes that lower viscosity despite their limited surface area (2.33 m

2 g

−1). These combined effects contribute to the observed reduction in plastic viscosity and improved overall rheological stability of the nanocrystalline oxide-enhanced WBDFs.

The yield point values (10.538–11.017 N/m

2) confirmed sufficient carrying capacity for cuttings. In terms of filtration control, Fe

2O

3 nanocrystalline oxide achieved the lowest API filtrate loss (6.0 mL) and a thin, compact mud cake (0.5 mm), outperforming ZnO and CuO systems (9.0 mL each). This superior performance can be attributed to the dense, quasi-spherical α-Fe

2O

3 crystallites (XRD D ≈ 38 nm, SEM

Figure 3) and their broader particle size distribution (DLS PDI ≈ 0.56), which promote tighter packing and efficient pore sealing. Conversely, despite its very fine primary particles (D ≈ 17 nm, BET 20.4 m

2 g

−1), CuO nanocrystalline exhibited slightly higher filtrate due to the formation of uniform micron-scale agglomerates (DLS Z-avg ≈ 1261 nm, PDI ≈ 0.36) that generate open filter-cake structures. ZnO, characterized by crumpled lamellar nanosheets (SEM) and a low surface area (2.3 m

2 g

−1), produced a higher filtrate volume due to irregular platelet stacking and interlayer gaps, consistent with its lower textural compactness revealed by BET analysis.

Although the BET surface areas of ZnO and α-Fe

2O

3 are relatively low, their inhibition performance in the present WBDF systems is not governed solely by adsorption-driven mechanisms. Nevertheless, the dominant contribution arises from physical sealing effects, including nanoplugging, pore bridging, and filter-cake structuring, which depend primarily on particle morphology, packing efficiency, and controlled secondary aggregation of nanocrystalline domains, rather than on high external surface area. This interpretation is supported by the experimental results, where the α-Fe

2O

3-based formulation exhibits superior filtration control (API filtrate volume of 6.0 mL and a thin mud-cake thickness of 0.5 mm;

Table 4), consistent with its dense, quasi-spherical nanocrystallites and broader aggregation distribution observed by SEM (

Figure 3) and DLS. Similarly, ZnO forms lamellar, plate-like aggregates that assemble into sub-micrometric secondary clusters (DLS Z-average ≈ 634 nm), enabling effective pore bridging and sealing despite its limited accessible N

2 surface area. Therefore, the low BET values primarily reflect the non-porous and partially aggregated nature of these oxides after calcination, rather than a lack of functional activity. Such behavior is well-documented in the literature, which demonstrates that shale inhibition and filtration performance in WBDFs are predominantly controlled by physical nanoplugging and filter-cake densification mechanisms governed by particle morphology and aggregation state, rather than by adsorption capacity alone [

65,

66,

67]. Consequently, metal oxide nanoparticles with relatively low BET surface areas can still deliver effective shale inhibition when their structural and aggregation characteristics favor efficient sealing of shale nanopores and microfractures.

MgO nanocrystalline oxide, featuring rough granular surfaces and moderate porosity (21.37 nm pores, BET 17.93 m

2 g

−1), provided balanced rheology and acceptable filtrate loss. The MgO-based fluid displayed the highest pH (10.0), confirming partial release of Mg

2+ ions and formation of carbonate species (600 mg L

−1), which can compress the diffuse double layer around clay edges and promote colloidal stability, an effect consistent with prior reports on alkaline earth oxides enhancing shale inhibition [

68,

69,

70,

71].

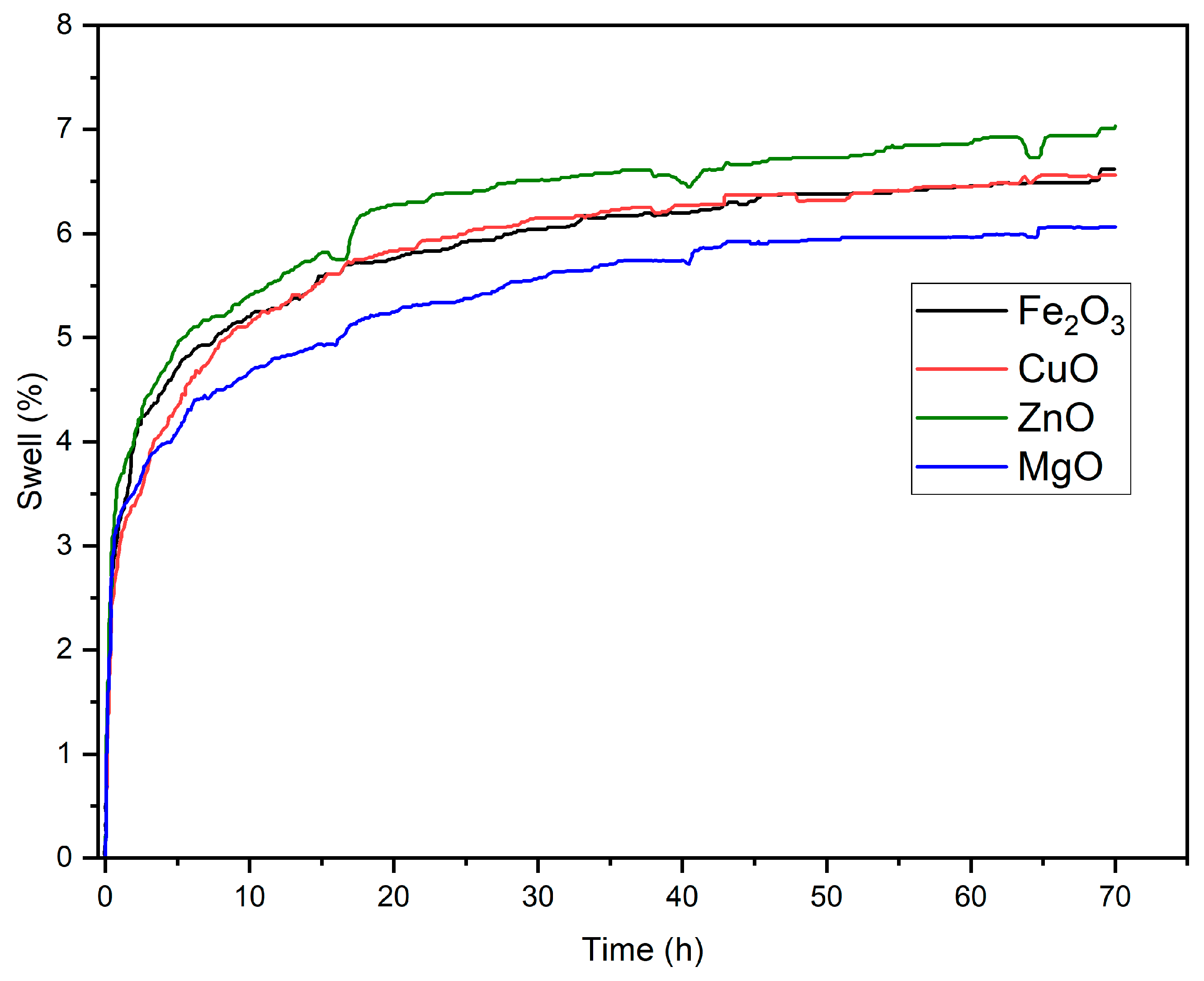

The dynamic linear swelling tests (

Figure 6) revealed a clear ranking in inhibition efficiency: MgO > Fe

2O

3 ≈ CuO > ZnO. After 70 h, the swelling was reduced to 6.1% (MgO), 6.6% (Fe

2O

3 and CuO), and 7.0% (ZnO), compared to 6.6% for the control WBM. The superior performance of MgO can be correlated with its highly basic nature, moderate particle size (DLS Z-avg ≈ 1438 nm), and mesoporous texture (pore mode ≈ 21.4 nm), which enable dual inhibition mechanisms: (i) physical nanoplugging of shale nanopores and (ii) ionic compression of the clay’s electrical double layer via released Mg

2+ and hydroxyl ions [

1,

72]. This behavior parallels the chemical inhibition mechanisms of amine-based additives through electrostatic interaction, yet without introducing organic residues into the fluid system. Fe

2O

3 nanocrystalline oxides provided strong filtrate control and moderate swelling inhibition (6.6%), consistent with their dense spherical morphology and mid-range surface area, which facilitate physical sealing of pore throats rather than ionic interaction. CuO showed a similar swelling reduction (6.6%) but with higher filtrate, suggesting that its soft agglomerates of fine tenorite crystallites act primarily via surface adsorption and hydrogen-bond interactions with clay hydroxyls, partially hindering hydration. Despite its chemical stability, ZnO exhibited the weakest inhibition (7.0%) due to its low surface area, lamellar shape, and minimal release of active ionic species resulting in insufficient intercalation into shale nanopores.

When benchmarked against commercial inhibitors from our previous work [

17], which reported shale swelling reductions of 6.3% (A-Lin), 7.0% (A-Lau), 6.7% (Amine NF), and 7.7% (Glycol), the current results demonstrate that MgO nanocrystalline oxide achieves comparable or slightly superior inhibition efficiency to A-Lin and Amine NF, despite their inorganic nature. Fe

2O

3 and CuO performed within the same range as Amine NF and Glycol, while ZnO displayed slightly higher swelling. This comparison highlights the complementary inhibition mechanisms: organic amine/glycol inhibitors rely primarily on surface adsorption and hydrophobic film formation, whereas inorganic oxides act through nanoplugging, ionic exchange [

69], and double-layer compression, with improved environmental compatibility and thermal resilience confirmed by TGA–DTG.

Integrating the findings from XRD, SEM, DLS, BET, and TGA–DTG analyses allows a coherent interpretation of the inhibition mechanisms. The structural purity and nanoscale crystallinity confirmed by XRD (17–38 nm) provide high surface reactivity and uniform particle–clay interactions. The distinct morphologies revealed by SEM granular (MgO), quasi-spherical (Fe2O3), lamellar (ZnO), and fine agglomerated (CuO) govern the mode of shale stabilization. Specifically, the rough granular MgO particles with mesoporous texture (pore mode ≈ 21.4 nm, BET 17.93 m2 g−1) and partial Mg2+ ion release promote electrostatic compression of the diffuse double layer and physical plugging of nanopores, leading to the strongest inhibition efficiency (6.1%). In contrast, Fe2O3 nanoparticles act primarily through mechanical sealing due to their compact, low-porosity, quasi-spherical aggregates (PDI ≈ 0.56), producing the lowest filtrate volume (6.0 mL) and a dense filter cake. Possessing the smallest crystallites (≈17 nm) and high surface area (20.47 m2 g−1), CuO exhibits significant surface adsorption and hydrogen-bonding interactions with hydroxylated clay sites, which moderately suppress hydration but do not achieve full plugging because of its soft micron-scale clusters (Z-avg ≈ 1260 nm). Conversely, the lamellar ZnO with limited active sites (BET 2.33 m2 g−1) demonstrates weaker inhibition due to poor intercalation and incomplete pore filling. DLS data support these interpretations, indicating that fluids with broader particle size distributions (e.g., Fe2O3) form tighter packing networks, while those with narrower or lamellar distributions (e.g., ZnO) create open microstructures. BET results further reinforce the importance of intermediate porosity as in MgO and CuO for achieving a balance between fluid mobility and effective sealing. Meanwhile, the TGA–DTG thermograms confirm that all oxide nanoparticles maintain structural and chemical integrity up to 350 °C, ensuring stability under HPHT conditions and reliable long-term inhibition. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the inhibition efficiency of nanoparticle-based WBDFs arises from a synergistic interplay between nanostructure, surface chemistry, and ionic reactivity. The dual mechanism physical pore plugging and electrochemical double-layer compression dominates in MgO and Fe2O3 systems, establishing them as the most effective and environmentally resilient additives for next-generation WBDF formulations.

Moreover, alongside their physicochemical and operational advantages, the use of inorganic metal oxide nanoparticles brings significant environmental benefits. By replacing conventional organic and polymeric inhibitors with thermally stable and chemically inert oxides, the proposed WBDF formulations eliminate the release of degradable organic residues and minimize the generation of toxic by-products. Furthermore, these oxide-based systems exhibit reduced ecological impact due to their non-volatile, non-flammable nature and long-term dispersion stability. Such characteristics align with the fundamental principles of sustainable chemistry, contributing to the development of greener and safer drilling fluid technologies that promote environmental protection and resource efficiency.

In comparison with previous studies discussed in the Introduction, which primarily focused on individual oxides or isolated performance metrics, the metal oxide nanoparticles synthesized in this work exhibit comparable or improved physicochemical and inhibition performance under application-relevant conditions. While ZnO- and CuO-based additives reported in the literature typically show crystallite sizes of 20–50 nm and shale swelling reductions of about 7–10% [

4,

14,

15], often evaluated individually and without extended aging or mechanistic analysis, the present study demonstrates that MgO and Fe

2O

3 achieve lower swelling values of 6.1–6.6% after 70 h while maintaining controlled rheology and reduced filtrate loss. Fe

2O

3, in particular, provides efficient filtration control (6.0 mL) at a lower plastic viscosity (19 cP) compared to previously reported Fe-based systems requiring higher viscosities (≈27 cP) for similar performance [

11]. Notably, MgO, previously reported to adversely affect filtrate behavior [

16], proves to be the most effective inhibitor due to its controlled aggregation, alkaline surface chemistry, and dual inhibition mechanisms involving nanoplugging and electrical double-layer compression. Unlike studies focused on single oxides or isolated metrics, this work establishes a systematic structure–property–performance relationship across Fe

2O

3, CuO, ZnO, and MgO evaluated under identical conditions. The integrated interpretation of XRD, SEM, DLS, BET, and TGA–DTG results provides mechanistic insight into how crystallite size, aggregation state, surface chemistry, and thermal stability collectively govern inhibition efficiency.

In the present study, the investigated metal oxide nanoparticles exhibit high chemical stability, non-volatility, and are applied at low concentrations within closed drilling fluid systems, which significantly limits their potential environmental dispersion. Unlike conventional degradable organic additives [

73], these inorganic oxides retain their structural integrity under high-pressure and high-temperature conditions, as confirmed by TGA–DTG analysis, which supports their classification as more robust and potentially safer alternatives when appropriate handling and disposal practices are applied.

In addition, the high thermal stability of metal oxide nanoparticles and their affinity toward acidic gases such as H

2S and CO

2 contribute to improved operational safety and performance in sour-gas, deep, and geothermal drilling environments, as reported in the literature [

65,

74]. This stability ensures that the nanoparticles remain functionally active in the drilling fluid over time without chemical degradation. Consequently, the identification, screening, and development of non-toxic and environmentally benign nanoparticle-based drilling fluids represent a promising pathway toward meeting current and future environmental regulations, particularly in deepwater and environmentally sensitive applications.